Abstract

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) occurs among persons aged <21 years following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Among 2818 MIS-C cases, 35 (1.2%) deaths were reported, primarily affecting racial/ethnic minority persons. Being 16–20 years old or having comorbidities was associated with death. Targeting coronavirus disease 2019 prevention among these groups and their caregivers might prevent MIS-C-related deaths.

Keywords: COVID-19, child, death, epidemiology, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a severe hyperinflammatory syndrome occurring among persons <21 years old typically 2–6 weeks after infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In previous analyses of MIS-C in the United States, minority racial/ethnic groups have been over-represented among cases, more than half of patients received intensive hospital care, and 2% of patients died [1, 2]. To inform clinical and public health decision-making, we aimed to describe demographic and clinical features among MIS-C decedents and factors associated with death.

METHODS

Since May 14, 2020, health departments have reported suspected MIS-C cases using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) standardized case report form with information abstracted from medical records. All cases reported by March 31, 2021, with known outcome (death or hospital discharge) and meeting the MIS-C case definition were included in the analysis. The MIS-C case definition included patients aged <21 years with fever, laboratory evidence of inflammation, and evidence of clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization, with multisystem organ involvement (cardiovascular, dermatologic, gastrointestinal, hematologic, neurologic, renal, or respiratory) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 or had exposure to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case within the 4 weeks before symptom onset (https://www.cdc.gov/mis-c/hcp/).

Underlying medical conditions were identified using the 9 conditions listed on the case report form, by categorizing free-text responses, or, for obesity, using anthropometric data [3]. An existing framework defining severe organ system involvement was adapted for the study [4]. To explore trends over time, the number of days between the first and last reported MIS-C onset dates were divided into 3 equal time periods (before June 29, 2020; June 29–November 6, 2020; and November 7, 2020–March 17, 2021), which aligned closely with waves of MIS-C reported in the United States. Demographic characteristics, clinical features, and management among survivors and decedents and factors associated with death are reported. Continuous variables were compared using medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs), and Kruskal-Wallis tests. After assessing for collinearity, categorical variables were compared using unadjusted exact logistic regression or logistic regression adjusted for age, obesity, nonobesity comorbidities, race/ethnicity, or MIS-C onset date, with 95% CIs, where sample size allowed. Data were analyzed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute).

Patient Consent

Factors necessitating patient consent did not apply to this study. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy [5, 6].

RESULTS

Fifty-one jurisdictions (48 US states, Washington, DC, New York City, and Puerto Rico) reported 3259 confirmed MIS-C cases. After excluding 441 cases with unknown outcomes (missing = 240 [7.4%]; hospitalized at time of reporting = 201 [6.2%]), 2818 MIS-C cases with onset dates during February 19, 2020–March 17, 2021, were analyzed (Table 1). Overall, 1664 (59%) MIS-C patients were male. Race/ethnicity was unknown for 359 (12.7%) persons; among those with available information, 909 (37.0%) were Hispanic/Latino, 709 (28.8%) were non-Hispanic Black, 28 (1.1%) were AI/AN, 29 (1.2%) were NH/PI, and 681 (27.7%) were non-Hispanic White persons. Thirty-five patients died. The overall case fatality ratio was 1.2% (95% CI, 0.1%–1.7%) and declined from 2.4% (95% CI, 0.1%–3.7%) to 1.6% (95% CI, 0.1%–2.5%) and 0.7% (95% CI, 0.03%–1.1%) across the 3 time periods (data not presented; χ 2P = .004).

Table 1.

Characteristics of MIS-C Cases, by Survival Status (n = 2818)—United States, February 2020–March 2021

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Survivors | Decedents | Crudea | Adjustedb | ||

| (n = 2818) | (n = 2783) | (n = 35) | ||||

| Sex (n = 2808) | ||||||

| Male | 1664 (59.0) | 1643 (59.0) | 21 (60.0) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 1.0d (0.5–1.9) | .89 |

| Female | 1144 (40.6) | 1130 (40.6) | 14 (40.0) | Ref | Ref | — |

| Age (n = 2811) | ||||||

| <1 y | 98 (3.5) | 97 (3.5) | 1 (2.9) | 1.6 (0.0–12.9) | NA | .98 |

| 1–5 y | 755 (26.8) | 749 (26.9) | 6 (17.1) | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 1.3e (0.4–3.8) | .67 |

| 6–11 y | 1112 (39.5) | 1105 (39.7) | 7 (20.0) | Ref | Ref | — |

| 12–15 y | 538 (19.1) | 532 (19.1) | 6 (17.1) | 1.8 (0.6–5.3) | 1.8e (0.6–5.5) | .29 |

| 16–20 y | 308 (10.9) | 293 (10.5) | 15 (42.9) | 8.1 (3.2–20.0) | 6.8f (2.7–17.1) | <.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 2459) | ||||||

| White, single-race; NH | 681 (27.7) | 676 (27.8) | 5 (16.7) | Ref | Ref | — |

| Black, single-race; NH | 709 (28.8) | 701 (28.9) | 8 (26.7) | 1.5 (0.5–4.7) | 1.2 (0.4–3.9) | .72 |

| Hispanic/Latinog | 909 (37.0) | 897 (36.9) | 12 (40.0) | 1.8 (0.6–5.2) | 1.4 (0.5–4.1) | .54 |

| Asian, single-race; NH | 57 (2.3) | 57 (2.3) | — | NA | NA | .96 |

| AI/AN; Hispanic, NH, or unknown ethnicity | 28 (1.1) | 26 (1.1) | 2 (6.7) | 10.3 (0.9–66.7) | NA | .06 |

| NH/PI; Hispanic, NH, or unknown ethnicity | 29 (1.2) | 27 (1.1) | 2 (6.7) | 9.9 (0.9–64.1) | NA | .06 |

| Multiple races (Black, White, Asian, “other”); NH | 46 (1.9) | 45 (1.9) | 1 (3.3) | 3.0 (0.1–27.6) | NA | .65 |

| Preexisting medical conditions | ||||||

| Any underlying medical conditionh | 1085 (38.5) | 1061 (38.1) | 24 (68.6) | 3.5 (1.7–7.3) | 2.8i (1.4–5.9) | <.01 |

| Obesity | 799 (28.4) | 783 (28.1) | 16 (45.7) | 2.2 (1.1–4.2) | 1.6j (0.8–3.2) | .17 |

| Chronic lung or airway disease | 260 (9.2) | 254 (9.1) | 6 (17.1) | 2.1 (0.9–5.0) | 1.6 (0.6–3.9) | .35 |

| Congenital heart disease | 66 (2.3) | 63 (2.3) | 3 (8.6) | 4.0 (0.8–13.5) | NA | .09 |

| Diabetes mellitus (type 1 or 2) | 26 (0.9) | 24 (0.9) | 2 (5.7) | 7.0 (0.8–30.0) | NA | .08 |

| Immunosuppression/malignancy/autoimmune disorder | 33 (1.2) | 30 (1.1) | 3 (8.6) | 8.6 (1.6–29.9) | NA | .01 |

| Neurologic disorder | 79 (2.8) | 74 (2.7) | 5 (14.3) | 6.1 (2.3–16.2) | 5.1 (1.9–14.1) | <.01 |

| Noncardiac congenital abnormality | 93 (3.3) | 86 (3.1) | 7 (20.0) | 7.8 (3.3–18.5) | 6.5 (2.6–16.0) | <.0001 |

| MIS-C illness | ||||||

| Date of onset (n = 2818) | ||||||

| Before Jun 29, 2020 | 538 (19.1) | 525 (18.9) | 13 (37.1) | 3.8 (1.7–8.7) | 4.2k (1.8–9.6) | <.001 |

| Jun 29–Nov 6, 2020 | 744 (26.4) | 732 (26.3) | 12 (34.3) | 2.5 (1.1–5.8) | 2.5k (1.1–5.8) | .04 |

| Nov 7, 2020–Mar 17, 2021 | 1535 (54.5) | 1525 (54.8) | 10 (28.6) | Ref | Ref | — |

| Days between MIS-C onset and hospital admission, median (IQR) | 4 (2–5) | 4 (2–5) | 3 (0–4) | NA | NA | <.01 |

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 6 (4–8) | 6 (4–8) | 6 (2–22) | NA | NA | .82 |

| Maximum temperature, median (IQR), °C | 39.7 (39.3–40.2) | 39.7 (39.3–40.2) | 39.4 (38.9–40.2) | NA | NA | .21 |

| Duration of fever, median (IQR), d | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–6) | NA | NA | .53 |

| Cardiovascular system involvement | ||||||

| Arrhythmia | 596 (21.1) | 583 (20.9) | 13 (37.1) | 2.2 (1.1–4.5) | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | .03 |

| Coronary artery dilation or aneurysm (n = 2666) | 421 (15.8) | 420 (15.9) | 1 (3.3) | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) | NA | .05 |

| Myocarditis | 422 (15.0) | 413 (14.8) | 9 (25.7) | 2.0 (0.9–4.3) | 1.5l (0.7–3.3) | .32 |

| Reduced cardiac function | 795 (28.2) | 779 (28.0) | 16 (45.7) | 2.2 (1.1–4.2) | 1.7l (0.9–3.5) | .12 |

| Elevated troponin | 1484 (52.7) | 1466 (52.7) | 18 (51.4) | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | 0.9l (0.4–7.7) | .66 |

| B-type or NT pro-B-type natriuretic peptide ≥1000 pg/mL | 992 (35.2) | 985 (35.4) | 7 (20.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | .11 |

| Shock | 1268 (45.0) | 1238 (44.5) | 30 (85.7) | 7.5 (2.9–19.4) | 5.9 (2.3–15.2) | <.001 |

| Severe cardiovascular involvementm | 2301 (81.7) | 2266 (81.4) | 35 (100.0) | 11.4 (2.5–∞) | NA | <.01 |

| Respiratory system involvement | ||||||

| Cough | 816 (29.0) | 796 (28.6) | 20 (57.1) | 3.3 (1.7–6.5) | 2.3l (1.1–4.6) | .02 |

| Pneumonia | 747 (26.5) | 722 (25.9) | 25 (71.4) | 7.1 (3.4–14.9) | 4.8l (2.2–10.2) | <.0001 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 162 (5.7) | 146 (5.2) | 16 (45.7) | 15.2 (7.7–30.2) | 9.5l (4.6–19.5) | <.0001 |

| Severe respiratory involvementn | 1289 (45.7) | 1255 (45.1) | 34 (97.1) | 41.4 (5.7–302.8) | 27.9l (3.8–205.3) | <.01 |

| Mucocutaneous involvement | ||||||

| Rash | 1571 (55.7) | 1558 (56.0) | 13 (37.1) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | 0.7l (0.3–1.4) | .30 |

| Mucocutaneous lesions | 646 (22.9) | 644 (23.1) | 2 (5.7) | 0.2 (0.0–0.8) | NA | .02 |

| Conjunctivitis | 1573 (55.8) | 1570 (56.4) | 3 (8.6) | 0.1 (0.0–0.3) | NA | <.0001 |

| Any mucocutaneous involvemento | 2110 (74.9) | 2095 (75.3) | 15 (42.9) | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | <.01 |

| Neurologic involvement | ||||||

| Encephalopathy | 76 (2.7) | 71 (2.6) | 5 (14.3) | 6.4 (2.4–16.9) | 5.4 (2.0–14.7) | <.01 |

| Meningitis | 105 (3.7) | 100 (3.6) | 5 (14.3) | 4.5 (1.7–11.8) | 4.7 (1.7–12.8) | <.01 |

| Stroke | 22 (0.8) | 15 (0.5) | 7 (20.0) | 46.1 (17.5–121.9) | 38.1 (13.0–111.1) | <.0001 |

| Severe neurologic involvementp | 179 (6.4) | 167 (6.0) | 12 (34.3) | 8.2 (4.0–16.7) | 7.7 (3.7–16.0) | <.0001 |

| Renal involvement | ||||||

| Acute kidney injury | 535 (19.0) | 518 (18.6) | 17 (48.6) | 4.1 (2.1–8.1) | 2.9 (1.4–6.0) | <.01 |

| Renal failure | 82 (2.9) | 71 (2.6) | 11 (31.4) | 17.5 (8.3–37.1) | 11.7l (5.3–26.0) | <.0001 |

| Severe renal involvementq | 567 (20.1) | 545 (19.6) | 22 (62.9) | 7.0 (3.5–13.9) | 4.8 (2.4–9.8) | <.000 |

| Hematologic involvement | ||||||

| Lymphopenia (age-based)r | 1104 (39.2) | 1092 (39.2) | 12 (34.3) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | .46 |

| Platelets <150 000/µL | 1195 (42.4) | 1177 (42.3) | 18 (51.4) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) | .18 |

| Deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism | 21 (0.7) | 19 (0.7) | 2 (5.7) | 8.8 (1.0–39.0) | NA | .05 |

| Severe hematologic involvements | 1751 (62.1) | 1727 (62.1) | 24 (68.6) | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) | .44 |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | ||||||

| Vomiting or diarrhea | 2245 (79.7) | 2222 (79.8) | 23 (65.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.5l (0.3–1.1) | .08 |

| Mesenteric adenitis | 330 (11.7) | 327 (11.7) | 3 (8.6) | 0.7 (0.1–2.3) | NA | .8 |

| Free fluid in abdomen or pelvis | 297 (10.5) | 294 (10.6) | 3 (8.6) | 0.8 (0.2–2.6) | NA | .98 |

| Liver failure | 28 (1.0) | 23 (0.8) | 5 (14.3) | 20.0 (7.1–56.1) | 11.2 (3.7–34.1) | <.0001 |

| Severe gastrointestinal involvementt | 721 (25.6) | 711 (25.5) | 10 (28.6) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | .74 |

Abbreviations: AI, American Indian; AN, Alaska Native; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; IVIG, intravenous immune globulin; MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; NA, not applicable; NH, Non-Hispanic; NH/PI, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.

aIf cell size was <5, we calculated unadjusted, exact parameter estimates.

bAdjusted for age (continuous, years), obesity (dichotomous), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

cFor categorical variables, we report chi-square or, if cell size <5, exact P values; for continuous variables we report Kruskal-Wallis P values.

dAdjusted for race/ethnicity (categorical), age (continuous, years), obesity (dichotomous), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

eAdjusted for race/ethnicity (categorical), obesity (dichotomous), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

fAdjusted for race/ethnicity (categorical), obesity (dichotomous), any underlying medical condition other than obesity (dichotomous), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

gOf any race other than AI, AN, NH, PI, or unknown race.

hUnderlying medical conditions included obesity, chronic lung or airway disease, congenital heart disease, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive or autoimmune disorders, malignancy, neurologic disorders, noncardiac congenital abnormalities, or sickle cell disease.

iAdjusted for race/ethnicity (categorical), age (continuous, years), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

jAdjusted for race/ethnicity (categorical), age (continuous, years), any underlying medical condition other than obesity (dichotomous), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

kAdjusted for age (continuous, years) and obesity (dichotomous).

lAdjusted for age (continuous, years), obesity (dichotomous), any underlying medical condition other than obesity (dichotomous), and MIS-C onset date (continuous, days).

mSevere cardiovascular system involvement included at least 1 of the following: arrhythmia, cardiac dysfunction (echocardiographic evidence of left or right ventricle dysfunction), congestive heart failure, coronary artery aneurysm or dilation, support using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, myocarditis, brain or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide level ≥1000 pg/mL, pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, elevated troponin (above upper limit of normal for the associated laboratory), receipt of vasopressor medications.

nSevere respiratory system involvement included at least 1 of the following: acute respiratory distress syndrome; pleural effusion; pneumonia; ventilatory support using high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, or intubation and mechanical ventilation.

oAny mucocutaneous involvement included at least 1 of the following: conjunctival injection, mucocutaneous lesions, rash.

pSevere neurologic involvement included at least 1 of the following: encephalopathy, meningitis, stroke.

qSevere renal involvement included at least 1 of the following: acute kidney injury, receipt of dialysis, renal failure.

rLymphopenia was defined as lymphocyte level <4500 cells/µL if age <8 months or <1500 cells/µL if age >8 months.

sSevere hematologic involvement included at least 1 of the following: deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, lymphopenia (lymphocyte level <4500 cells/µL if age <8 months or <1500 cells/µL if age ≥8 months); neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count <500 cells/µL), thrombocytopenia (platelets <150/µL).

tSevere gastrointestinal involvement included at least 1 of the following: appendicitis, radiographically diagnosed enteritis/ileitis/colitis, free fluid in abdomen or pelvis, gallbladder hydrops, hepatomegaly, liver failure, mesenteric adenitis.

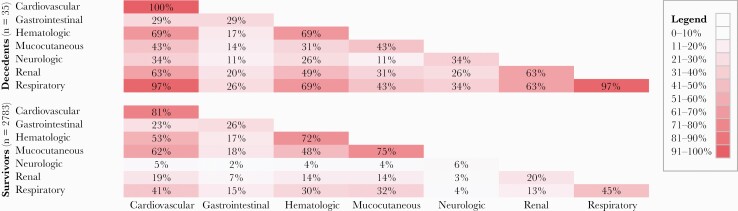

The median age among decedents (IQR) was 15.8 (7.9–17.8) years (data not presented), and 15 (42.9%) deaths occurred among persons aged 16–20 years. Among 30 decedents with known race/ethnicity, 12 (40%) were Hispanic/Latino, 8 (26.7%) were non-Hispanic Black, 2 (6.7%) each were American Indian (AI)/Alaska Native (AN) and Native Hawaiian (NH)/Pacific Islander (PI), and 5 (16.7%) were non-Hispanic White. One or more underlying medical conditions were reported for 24 (68.6%) decedents; obesity was most commonly reported (n = 16; 45.7%). Thirty-one (88.6%) decedents were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) (Supplementary Table 1). Death occurred a median (IQR) of 12 (5–19) days after MIS-C onset (data not presented) and 6 (2–22) days after hospitalization. Decedents experienced severe involvement of a median (IQR) of 4 (4–5) organ systems. All had severe cardiovascular involvement, and 34 (97.1%) had both severe cardiovascular and respiratory system involvement (Figure 1). Thirty (85.7%) decedents received vasopressor medications for shock, and 12 (34.3%) received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) therapy; 1 (3.3%) of 30 who underwent echocardiography had coronary artery dilation or aneurysm. Acute kidney injury was reported among 17 (48.6%) decedents; 5 (14.3%) required dialysis. More than one-third of decedents (n = 12; 34.3%) had severe neurologic involvement, including 7 (20%) with stroke. Nineteen (54.3%) decedents received at least 1 dose of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and 14 (40.0%) received both IVIG and glucocorticoids.

Figure 1.

Heatmap showing the percentage of MIS-C decedents and survivors with severe involvement of individual and 2-way combinations of organ systems. Boxes representing a single organ system show the percentage of persons who had severe involvement of that system. Percentages sum to >100% because each patient’s illness could involve multiple combinations of organ systems. Abbreviation: MIS-C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children.

On multivariable analysis, the odds of death were higher among persons aged 16–20 years than among children aged 6–11 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 6.8; 95% CI, 2.7–17.1) (Table 1). The odds of death were higher among AI/AN and NH/PI persons, but the associations were not statistically significant. Having 1 or more underlying comorbid medical conditions was associated with death (aOR, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.4–5.9), particularly neurologic disease (aOR, 5.1; 95% CI, 1.9–14.1) or noncardiac congenital abnormalities (aOR, 6.5; 95% CI, 2.6–16.0). Severe involvement of the following organ systems was also associated with dying: cardiac (OR, 11.4; 95% CI, 2.5–∞), respiratory (aOR, 27.9; 95% CI, 3.8–205.3), neurologic (aOR, 7.7; 95% CI, 3.7–16.0), or renal (aOR, 4.8; 95% CI, 2.4–9.8), whereas mucocutaneous involvement was inversely associated with death (aOR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.18–0.75). The odds of death among patients who developed stroke, renal failure, or liver failure were 38, 12, and 11 times as high, respectively, as the odds among those without these complications.

DISCUSSION

As of March 31, 2021, among 2818 MIS-C cases, 35 (1.2%) MIS-C-related deaths had been reported to the CDC. Although other investigators have reported the highest MIS-C incidence among primary school–aged children [1], we found that the highest number and likelihood of death occurred among persons aged 16–20 years. Previous analyses have found ICU admission to be more likely among MIS-C patients aged 13–20 years and SARS-CoV-2-related death to be more common among persons aged 10–20 years than among younger children [2, 5]. Together, these findings suggest that adolescents and young adults are at highest risk for severe MIS-C outcomes.

These data were limited by sample size and incomplete ascertainment of race/ethnicity, yet they suggest increased MIS-C incidence and mortality among racial/ethnic minority groups. Although Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic Black, AI/AN, and NH/PI persons account for approximately one-third of the US population, more than two-thirds of MIS-C cases and 80% of MIS-C deaths occurred among these groups [8]. These findings are consistent with disparities in COVID-19 incidence, mortality, and case fatality rates among Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic Black, AI/AN, and NH/PI persons reported elsewhere [5, 9–11]. Improving clinical and public health information systems to ascertain race/ethnicity uniformly and completely across jurisdictions would permit more robust analyses and help guide policy-makers, health departments, clinicians, and community partners to address systemic issues that contribute to health disparities.

Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of underlying medical conditions among pediatric COVID-19 decedents [5]. In this report, 69% of MIS-C decedents had 1 or more underlying medical conditions, and preexisting neurologic disease or noncardiac congenital abnormalities were associated with death.

During MIS-C illness, severe involvement of the respiratory, cardiac, neurologic, or renal systems was associated with death. All decedents had severe cardiovascular involvement, with most requiring vasopressor medications for shock and one-third receiving ECMO. Stroke was reported among 20% of decedents and was associated with 38-fold increased odds of death. In a previous report about youths with SARS-CoV-2-related illness, severe neurologic involvement was associated with high mortality rates as well as neurologic sequelae among survivors [12].

During February 2020–March 2021, the likelihood of dying among those with MIS-C decreased while the numbers of MIS-C cases increased. Decreasing mortality might be related to increasing identification and reporting of milder MIS-C cases, improvements in clinical management, changes in the SARS-CoV-2 virus, or some combination of these or other factors. Evidence to guide the clinical management of patients with MIS-C continues to accrue, and recent reports suggest that treating patients with IVIG and glucocorticoid medications may improve outcomes [13–15]. Additional studies would be useful to elucidate the incidence, trends, and optimal clinical management of MIS-C.

Because this was an exploratory analysis with multiple comparisons and small numbers of decedents, the results presented should be interpreted cautiously. This report might be further limited by biases related to variations in diagnosis and reporting across jurisdictions and time. Because the MIS-C case definition is broad and the case report form did not include explicit definitions of underlying medical conditions, signs/symptoms, complications, or timing of the clinical course, misclassification is possible. Finally, information about specific causes of death was not collected.

This report is among the first to examine MIS-C mortality and can inform prevention efforts. At the time of this study, only 60% of decedents met the current age-based eligibility requirements for COVID-19 vaccination. Because large numbers of children and adolescents will remain at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection until COVID-19 vaccine access expands, clinicians must remain vigilant for MIS-C. Children and their caregivers should be supported to practice nonpharmaceutical methods of preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission [16]. Vaccinating adults can protect unvaccinated children and should be encouraged [17]. Facilitating vaccination among persons aged 12–20 years, which includes the age group with the largest number of deaths and highest odds of death associated with MIS-C, is currently possible. As vaccine eligibility expands, similar efforts could be undertaken for younger children. Prioritizing COVID-19 prevention efforts, including vaccination, among persons of minority racial/ethnic groups and those with underlying medical conditions would help protect those at highest risk for severe MIS-C-related outcomes [2, 5].

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

State, local, and territorial health departments; Joseph Abrams, Michael Melgar, CDC.

Financial support. None.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Author contributions. A.B. conceived of the study; A.B., L.D.Z., and A.P.C. contributed to study design; A.B., A.D.M., and M.J.W. cleaned and validated the data; A.B., A.D.M., and L.D.Z. contributed to data analysis; A.B. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; A.B., A.D.M., L.D.Z., and A.P.C. edited the manuscript; A.B. and A.P.C. provided study supervision; all co-authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

References

- 1.Belay ED, Abrams J, Oster ME, et al. Trends in geographic and temporal distribution of US children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr 2021; 175:837–45. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams JY, Oster ME, Godfred-Cato SE, et al. Factors linked to severe outcomes in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in the USA: a retrospective surveillance study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2021; 5:323–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining childhood obesity. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html#:~:text=Body%20mass%20index%20%28BMI%29%20is%20a%20measure%20used,and%20teens%20of%20the%20same%20age%20and%20sex. Accessed 13 April 2021.

- 4.Feldstein LR, Tenforde MW, Friedman KG, et al. ; Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators. Characteristics and outcomes of US children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) compared with severe acute COVID-19. JAMA 2021; 325:1074–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HHS. Code of Federal Regulations;45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2), 21 C.F.R. part 56. [cited 2021 August 5h 2021]. Available at: https://ecfr.federalregister.gov/

- 6.Office of the Law Revision Counsel. United States Code; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq. [cited 2021 August 5h 2021]. Available at: https://uscode.house.gov/

- 7.Bixler D, Miller AD, Mattison CP, et al. ; Pediatric Mortality Investigation Team. SARS-CoV-2-associated deaths among persons aged <21 years - United States, February 12-July 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United States Census Bureau. Population estimates, July 1, 2019 (V2019). Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed 26 April 2021.

- 9.Arrazola J, Masiello MM, Joshi S, et al. COVID-19 mortality among American Indian and Alaska native persons - 14 states, January-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1853–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. NHPI COVID-19 Data Policy Lab Dashboard. UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. Available at: http://ask.chis.ucla.edu/health-profiles/Pages/NHPI-COVID-19-Dashboard.aspx. Accessed 9 April 2021.

- 11.Williamson LL, Harwell TS, Koch TM, et al. COVID-19 incidence and mortality among American Indian/Alaska Native and White persons - Montana, March 13-November 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021; 70:510–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaRovere KL, Riggs BJ, Poussaint TY, et al. ; Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators. Neurologic involvement in children and adolescents hospitalized in the United States for COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78:536–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McArdle AJ, Vito O, Patel H, et al. Treatment of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:11–22.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Son MBF, Murray N, Friedman K, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children — initial therapy and outcomes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:23–34.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouldali N, Toubiana J, Antona D, et al. ; French Covid-19 Paediatric Inflammation Consortium. Association of intravenous immunoglobulins plus methylprednisolone vs immunoglobulins alone with course of fever in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. JAMA 2021; 325:855–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for unvaccinated people: how to protect yourself & others.2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed 6 April 2021.

- 17.Milman O, Yelin I, Aharony N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection risk among unvaccinated is negatively associated with community-level vaccination rates. medRxiv 2021.03.26.21254394 [Preprint]. 31 March 2021. Available at: 10.1101/2021.03.26.21254394. Accessed 10 April 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.