Abstract

Australia suffered two waves of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in 2020: the first lasting from February to July 2020 was mainly caused by transmission from international arrivals, the second lasting from July to November was caused by breaches of hotel quarantine which allowed spreading into the community. From a second wave peak in early August of over 700 new cases a day, by November 2020 Australia had effectively eliminated community transmission. Effective elimination was largely maintained in the first half of 2021 using snap lockdowns, while a slow vaccination programme left Australia lagging behind comparable countries. This paper describes the interventions which led to Australia's relative success up to July 2021, and also some of the failures along the way.

Key words: COVID-19, Australia, elimination strategy, vaccination

1. Introduction

On 1 November 2020, Australians woke to good news. It was national ‘doughnut day’. And no, we do not mean the sweet pastry. There was something even sweeter to enjoy: the first day of zero new community-acquired coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases Australia-wide since June 2020.

Australia is one of the few countries in 2020 that was able to bring new community-acquired COVID-19 cases down to zero. While not immune to the devastating virus, Australia's COVID-19 waves have been small, compared to many other countries.

Australia, with a population of 25 million, had two distinct waves of infection in 2020 with a cumulative total of about 28,000 cases and 900 deaths – about 110 cases and 4 deaths per 100,000 people. The vast majority of the 2020 cases and deaths came from Australia's second wave – which was much longer and more severe than the first, despite largely being contained within one city, Melbourne. In the first half of 2021, Australia had very few cases in the community, with intermittent short lockdowns to control any cases leaked into the community from quarantine.

Widespread testing, contact tracing, border closures and lockdowns – while not perfect – have been the major tools to reduce, and in some cases, eliminate community transmission. While vaccination is the best longer-term tool for managing the pandemic, the vaccine roll-out has been badly managed, and consequently very slow, with only 10% of the population fully vaccinated 5 months into the programme (Figure 1).

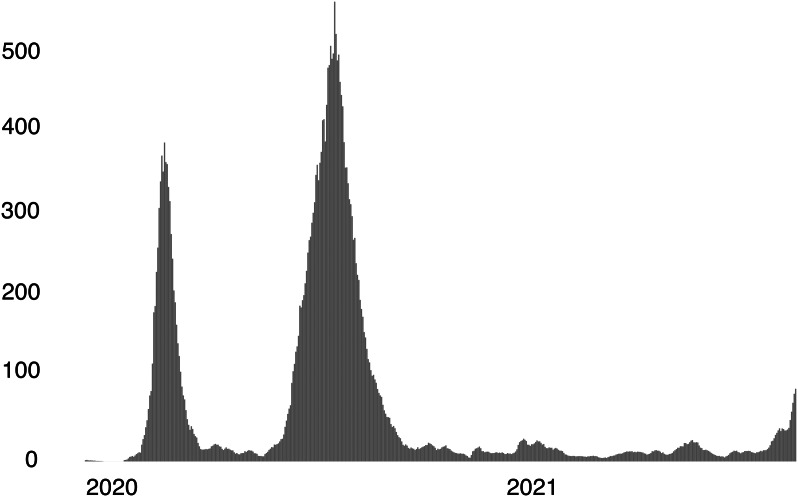

Figure 1.

Australia had two waves of COVID-19 infections as at July 2021. Seven-day moving average of new COVID-19 cases in Australia, 2020−21.

Source: Ritchie et al. (2020).

2. Part one: The Australian story (2020 to July 2021)

2.1. Wave one: Containing COVID at the border

It was a hot summer day on 25 January when Australia recorded its first COVID-19 case in Melbourne. Slowly, as the case count grew over the next six weeks, the distant threat of a looming pandemic started to become a reality.

2.1.1. Initial border response

Cases began to trickle into Australia via travellers returning from China. Over February, the risk rapidly escalated as COVID-19 spread globally. By March, more and more travellers arriving in Australia tested positive, particularly those coming from the United States and Europe. The Commonwealth (federal) government-imposed travel restrictions on top of an early ban on arrivals from China; first targeted at specific countries – Iran, South Korea, and belatedly Italy – and then at all non-residents by 20 March.1 This was followed on 28 March by mandatory two-week hotel quarantining of Australian international arrivals, still in place today. At the same time, exercising their powers and responsibilities for public health, most of the eight states shut their borders to other states to prevent the spread from higher-risk areas.

2.1.2. National lockdown

When daily case numbers pushed past 200 in mid-March, an escalated nationally consistent response was instituted by the Prime Minister calling together leaders of all state governments in the form of a roundtable called ‘the national cabinet’. It met weekly to build consensus on social distancing and lockdown measures.

Very quickly, as new cases reached over 400 per day – mostly from overseas arrivals – all states went into partial lockdown. Many non-essential businesses closed their doors, schools mostly closed and went online, and Australians stayed at home ‘where possible’. Retail remained open and cafes and restaurants could do take-away.

The Commonwealth government rolled out a succession of economic response packages, including increased support for the unemployed – JobSeeker – and a wage subsidy for struggling businesses – JobKeeper.

For two months, Australian life slowed, and the rate of new COVID-19 cases fell, both from international arrivals and from transmission in the community.

By early May, COVID-19 cases were down to fewer than 20 new cases a day. Australians cautiously breathed a sigh of relief. By this stage, Australia had had in total about 7000 cases and 200 deaths, with two-thirds of the cases linked to quarantined travellers coming from overseas.

With new-found hope about containing the virus, and amid fears about the economic fallout escalating, on 8 May the national cabinet announced a three-step recovery plan to ease restrictions. Despite the Prime Minister seeking national consistency, the states adopted a ‘go-it-alone’ approach, with some easing restrictions faster than others, and endorsing localised responses to any outbreaks. Although Australia's international borders remained tightly closed, it was only a matter of time until cases would leak from quarantine into the community, and result in further outbreaks.

2.2. Wave two: Eliminating COVID-19 in the community

In mid-June when restrictions were partially eased, cases in Australia began to rise again, but this time, the infections were largely localised to one of Australia's eight jurisdictions – Victoria, of which Melbourne is the capital. The state of Victoria is home to a quarter of Australia's population – about 6.5 million people. Compared to second waves in other countries, Australia's second wave came early and proved to be relatively small. But it was much bigger than the first, and it had much more community spread. Other Australian states closed their borders to Victoria, keeping the rest of Australia largely COVID-free.

2.2.1. Quarantine breach

The second wave started with growing case numbers in Victoria in late June 2020, which were linked back to breaches in the state's hotel quarantine of international travellers. Social distancing restrictions were fairly relaxed at this stage, and COVID-19 quickly spread before public health authorities could control it.

2.2.2. Tackling the hotspots

Clusters began popping up in numerous locations, particularly in Melbourne's poorer suburbs. Health authorities targeted the ‘hotspots’ with a testing blitz – testing anyone, whether with or without symptoms – scrambling to prevent further spread. New cases were being discovered at a rapidly rising rate, growing from 40 to 60 new cases a day. In an effort to target high-risk areas, on 1 July the Victorian government put 10 postcodes across Melbourne into lockdown. Three days later, a further two postcodes were added to the list.

But this targeted response quickly proved to be insufficient. New cases continued to rise, breaching 100 new cases per day. Cases could not effectively be contained within dispersed suburbs of a major city, because people are connected to other areas through work and family. So, on 8 July the Victorian government extended the lockdown to the whole of Melbourne. Initially it was declared for six weeks, but after a month of unrelenting growth in cases that would have taken six months to control, the government announced a much stricter lockdown to more rapidly drive down transmission.

2.2.3. Strict and long lockdown

Victoria's second wave lockdown was strict and long – but ultimately proved effective. It included school and childcare closures, business-wide and retail shutdowns, with limited numbers permitted to work in certain industries, such as construction, and take-away only for cafes and restaurants. People were required to stay at home unless exercising or essential shopping. Exercise was limited to one hour a day. Shopping was limited to one person per household per day. Masks were mandatory both indoors and outdoors. Travel was restricted to a 5 km radius. It even included a night-time curfew – with no-one allowed outside past 8 pm. An internal, policed ‘border’ between Melbourne and the rest of the state further restricted travel.

2.2.4. Containing spread at the border

Meanwhile, other states witnessing the crisis unfolding in Victoria put a tighter seal on their internal borders. From 8 July, the neighbouring state to the north, New South Wales, closed its border to all Victorians – the first border closure between these two states in more than a century.

Other states either already had border restrictions in place and/or enhanced them against Victorian travellers – banning entry or, if an exemption applied, requiring them to either self-isolate for 14 days or quarantine on arrival in the other state. But the border closures were not without their problems. Border towns were thrown into chaos, and it affected people who commute from one state to another. The change left some healthcare workers unable to get to work, and even patients unable to see their healthcare providers.2

One Australian state – Western Australia – took a particularly strong position on border closures. The Premier was clear that a hard border around the state would remain ‘as long as it [took] to protect people and keep our economy functioning within our borders'.3 Tough penalties applied – and one woman who snuck across the border on a truck travelling from Victoria was even sentenced to six months in jail.

2.2.5. Leakage into the neighbouring state

Despite the border closure, New South Wales, Australia's most populous state, was unable to avoid being affected. Clusters linked to pubs and restaurants were traced back to Victoria, but authorities jumped on these quickly and traced down the cases, with the state bumping along at below 20 cases a day. Restrictions were progressively but not dramatically increased. This process of small, frequent increases to restrictions was the policy choice of the NSW state government.

2.2.6. It got worse before it got better

Meanwhile, despite the strict lockdown, widespread community transmission continued to rage on in Victoria for weeks – growing to over 700 new cases about four weeks after the Melbourne-wide lockdown began. Victoria faced a local case transmission rate about eight times higher than its peak during the first wave (excluding overseas arrivals in quarantine). It would take many weeks to bring cases down again, with the lockdown only ending after 112 days, at the end of October 2020.

Although COVID-19 case numbers did not leap high enough to threaten Victoria's health system capacity, it still had an impact. Of the 20,000 people infected during the second wave, nearly 20% were healthcare workers – most of whom had been infected in the workplace. Of these, about a third were nurses, and nearly half were aged-care workers.

2.2.7. The path to ‘COVID normal’

On 6 September, when daily cases were down to fewer than 100 a day, the Victorian Premier announced a ‘roadmap’ to reopening. The three-step roadmap to ‘COVID normal’ for Melbourne and regional Victoria was largely driven by case number thresholds (using 14-day averages), rather than dates.4 With this, the government sought to find a middle ground between providing some certainty, while not allowing the hard work of lockdown to be undone. It wasn't good enough to merely bring cases down – the lockdown would only ease once there were fewer than five daily cases on a 14-day rolling average. Modelling showed that this threshold would significantly reduce the chance of a third or fourth wave.

This plan took a strategic approach to easing restrictions, keeping clamps on higher-risk settings. Large workplaces would remain closed for as long as possible, and households were not permitted any or only a few guests for months. The government instead steered the public to lower-risk outdoor settings. As spring and then summer kicked in, Melburnians flocked to parks to catch-up with friends and family not seen in months.

Gradually, Victoria met the case number thresholds, and restrictions were eased. Despite the detailed, and arguably overly complex roadmap, the government did not strictly comply with it – sometimes being more cautious than was initially planned, and sometimes less. Victorians became accustomed to the Premier, every few Sundays, making announcements about changes to the rules. TV networks broadcast his media conferences.

By the end of October, the Melbourne lockdown ended. Retail, cafes, and restaurants opened their doors. And by early November, Victoria not only recorded a few ‘doughnut days’, but many consecutive days.

2.3. 2021: Maintaining elimination and rolling out vaccinations

During the first half of 2021, Australia remained largely COVID-free. With barely any cases in the community, and only minor COVID restrictions in place, Australians could effectively go back to life as normal. Any risk of new cases came from quarantine, where international arrivals were required to undertake 14-days of hotel quarantine. But leaks inevitably happened – there were 14 breaches up 31 March 2021 – with these leaked cases managed through contact tracing or snap lockdowns – mostly lasting between a few days and two weeks. A larger outbreak starting in June 2021 required more extended lockdowns in both Melbourne and Sydney, made more difficult due to the virulence of the Delta strain.

The vaccine rollout was slow to start – it did not begin until February 2021, and was poorly implemented. Vaccinations were primarily to be administered through doctors at health clinics, with mass vaccination initially not part of the plan. The phasing prioritised frontline workers such as quarantine and health workers, and vulnerable populations, including aged care residents, and people with disability. A significant minority of Australians were vaccine hesitant throughout the first half of 2021, with about a quarter of Australians reporting that they were not likely to get vaccinated.

3. Part two: The ups and downs of Australia's response (2020–July 2021)

Australia's unique COVID-19 story has been defined by both luck and collective hard work, resulting in one of the few countries that was able to become largely COVID-free after a significant outbreak.5

Australia was successful in turning an outbreak around from peaking at 700 cases in one day, to reducing it to zero four months later.6

3.1. What worked: A collective effort

Although Australia's response to COVID-19 has been far from perfect, there have been some key successes that carried the country through.

3.1.1. Border closures

Australia's first wave was repelled at the country's border. The overwhelming majority of new cases during the first wave were directly linked to overseas travel, with international sources accounting for nearly two-thirds of Australia's total infections at the time. The government's strict control measures on its border – to ban all non-citizens and non-resident travellers on 20 March and then requiring 14-day mandatory hotel quarantine for all international arrivals on 28 March, was a turning point.7 Australians needed an exit-visa to leave the country. Because of the cap on arrivals, economy-class travel almost disappeared, leaving many Australians stranded overseas, unable to afford to return home.

Border closures in general have been an effective tool in Australia's COVID-19 response. Border restrictions between some Australian states appeared to keep most of Australia COVID-free during Victoria's second wave.

There was a constitutional challenge to the state-border closures but, as part of that case the court charged with determining the facts found that the ‘the border restrictions [had] been effective to a very substantial extent to reduce the probability of COVID-19 being imported into Western Australia from interstate’.8 Australia's top court then held that the state-imposed border closures did not breach the constitution provision that ‘trade and intercourse between the states shall be absolutely free’.9

3.1.2. Initial national cooperation

An important part of Australia's first wave was the formation of the national cabinet, comprising the Prime Minister and the leaders of each state government.

The states have primary responsibility for public hospitals, public health, and emergency management, including the imposition of lockdowns and social distancing restrictions. The national government has primary responsibility for income and business support programmes. The coordination of these responsibilities was crucial.

Cooperation between states and the national government – no matter where they sit on the political spectrum – helped get a nationally consistent response to the crisis partly by making decisions by consensus, but also partly by explicitly endorsing different options. In the early stages of the pandemic, the national cabinet helped individual states justify strong decisions, through this collective approach. During the first wave the national cabinet met weekly, and then later, monthly.

3.1.3. Evidence-based decision making

National cooperation was further enhanced by the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee, comprising the nation's chief medical officer and his state counterparts (generally called chief health officers). From the start of the crisis, this forum met daily for two hours and helped underpin Australia's policy decisions with public health expertise, particularly with regard to social distancing measures.

Evidence-based decision making was particularly crucial during the second wave, when cases were spreading out of control. The Victorian government's lockdown strategies were largely driven by modelling that informed decision makers about case thresholds that could reduce the risk of future resurgences. Rather than look at the immediate future, the government looked at a longer-term time horizon that would minimise the chance of third or fourth waves.

3.1.4. Public support

There was widespread public acceptance of social distancing measures, demonstrated by people's adherence to the rules.

And while there has been a loud minority of people, including some business leaders, expressing frustrations at the long and harsh rules imposed on Victorian during the second wave, most people were supportive. In August, at the height of Victoria's strict lockdown, a poll showed that Victorians overwhelmingly supported most restrictions, including mask wearing, the night-time curfew, and the 5 km limit on travel.10

3.1.5. Public health infrastructure

Australia's universal health system means that if someone has symptoms, they can easily get tested for free. Australia has one of the highest testing rates in the world.

If people need to consult a medical practitioner, they can do so over the phone or via videoconference, as the national government responded by making ‘telehealth’ immediately available. A survey of more than 1000 doctors found 99% of practices offered ‘telehealth’ services, alongside 97% continuing to offer face-to-face consultations.11

Although Australia's health system capacity has not been overwhelmed, steps were taken quite quickly to expand capacity if it was needed – with public hospitals suspending non-urgent elective surgeries and private hospitals being at the ready to help out.

In recognising the mental health toll of the pandemic and the lockdown, governments have significantly expanded their support for mental health programmes.12 Although there has been a spike in calls to mental health hotlines, there has been no clearly identifiable increase in the suicide rate to date.13

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people also led responses to COVID-19.14 Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations took a lead in communicating COVID-19 health issues, and land councils moved early to prepare communities.15

3.1.6. Economic support for the vulnerable

On the economic front, Australia, like much of the world, entered into a recession. But a suite of significant economic support measures from state governments and (predominantly) the national government has been largely successful. In 2020 alone, recovery and support measures amounted to national government spending of $370 billion USD equivalent (25% of Australia's GDP), including $190 billion USD in direct economic support.16

Most significantly, the conservative national government introduced a wage subsidy scheme. The scheme, designed to keep people on the payroll, paid workers via their employer a flat rate of USD equivalent of $550 per week – about 70% of the typical wage in Australia. It is estimated that this scheme reduced total job losses by at least 700,000.17

The national government also temporarily doubled welfare benefits for the unemployed to $400 USD a week – with the unemployment rate expected to peak at nearly double the pre-crisis rate. Women and young people were the most likely groups to lose their jobs. The unemployment rate reached 7% in October 2020, but by May 2021, unemployment was lower than it was pre-pandemic. And after a bumpy year, aggregate Australian consumption was back to normal by November 2020.

3.1.7. Choosing the right strategy

While contested, the elimination strategy proved effective at reducing both health and economic costs. Once Australia had COVID cases down to near zero, cases could more easily be traced, without resulting in significant outbreaks.

Australia has had fewer COVID cases and deaths as a proportion of its population than most countries in the world, sitting behind New Zealand and Taiwan. While in August 2020 Victoria had similar case numbers to several other countries, including the UK, those other countries not only recorded many more deaths, but also went into much longer lockdowns.

And while the lockdowns had significant costs, Australia ultimately had more days free from restrictions than most other countries. This enabled better economic outcomes, with Australia having a shorter recession than most other countries. It has also proved politically attractive, with other state leaders that have maintained strict borders and low cases numbers, sustaining high levels of public support.

3.2. What didn't work: It has not all been smooth sailing

An Australian parliamentary inquiry found in its December 2020 report that ‘while Australia [had] avoided the worst of the potential health outcomes’, ‘more could have been done to prevent illness and this tragic loss of life’.18

3.2.1. Mistakes and quarantine failures

About 2700 passengers from the Ruby Princess international cruise ship were allowed to disembark freely in Sydney on 19 March 2020, despite some showing COVID-19 symptoms. The ship became Australia's largest single source of infection during the first wave. A special commission of inquiry found that ‘in light of all the information the [decision-makers involved] had, the decision to assess the risk [of the passengers being potentially infected with COVID-19] as ‘low risk’ – meaning, in effect, ‘do nothing’ – is as inexplicable as it is unjustifiable. It was a serious mistake’.19

Victoria's second wave can primarily be traced back to breaches in infection protocols in that state's hotel quarantine programme.20 Victoria's reliance on private security guards rather than police or the defence force – used in other states – has been heavily criticised. A government-appointed inquiry is looking into the case.21

Outbreaks in 2021 were also linked to leakages from hotel quarantine, leading to more localised lockdowns in different Australian cities where the leaks occurred, resulting in about one lockdown per month, on average. A June 2021 study found that for every 1000 COVID cases in quarantine, there were 5.8 cases that transmitted to people in the community.22 While the numerous failures in hotel quarantine arrangements demonstrated the need for better purpose-built facilities, as was recommended by a national review in November 2020, very few steps had been taken to do so.

3.2.2. Lack of preparedness and adequate systems

Australia's pandemic response was slow to get started. Although Australia had faced epidemics in the recent past – most recently the H1N1 virus – its preparedness regimes were more geared towards a similar flu-like virus, with the measures such as the closure of international borders, not contemplated in the plan. A parliamentary inquiry into Australia's response to COVID-19 found that ‘the government did not have adequate plans in place either before, or during the pandemic’.23

Australia was also too slow in some areas to prepare its health system for the prospect of the virus spreading rapidly. Australia struggled initially to meet the rising demand for PPE. Australia's stockpile of 12 million P2/N85 masks and nine million surgical masks was not sufficient, and neither had it stockpiled enough gowns, visors, and goggles to cope with the crisis. The parliamentary inquiry found that there had been warnings prior to the pandemic that the stockpile was inadequate, but that the government had failed to heed this.

In some cases, contact tracing was not sophisticated. A national contact tracing review, released in November 2020, found that in some jurisdictions, ‘interviews with contacts are recorded on paper before being entered into a database, causing delays and the potential for error’.24 The Victorian government was still using a paper-based system to record confirmed cases and trace their contacts.25 A Victorian Parliamentary review found that ‘the use of manual data entry processes at the beginning of the pandemic meant that the system for contact tracing and recording of testing was not fit to deal with any escalation of cases and led to significant errors’.26 This was not helped by the failure of the Australian government's contact tracing app ‘COVIDSafe’ to provide more than a handful of identified contacts.27

Most fatally, the national government – which has responsibility for aged care – did not have an adequate COVID-19 plan for aged care,28 and did not rapidly develop one following the tragic outbreaks in residential care during the first wave. Similar outbreaks in aged care homes in Victoria during the second wave were not handled any better. A Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety did a special report on COVID-19, and found there was poor planning and leadership, with confused and inconsistent communication from aged care providers and government.29 The report found that ‘all too often, providers, care recipients and their families, and health workers did not have an answer to the critical question: who is in charge?’ By the end of the second wave in October, there had been about 2000 COVID-19 cases and 680 deaths in residential aged care – mostly in Victoria – accounting for about 75 per cent of Australia's total death toll. This is higher than many comparable countries, where about half of all COVID-19 deaths have been in aged care homes.30

3.3. Contested issues

3.3.1. Setting the right strategy

In early 2020, the lack of a clear, overarching national strategy for COVID-19 resulted in a reactive policy approach, featuring confusing messages. The Commonwealth and state governments had different positions on how best to manage COVID-19. Public discourse was heated, with debate between people who argued that lockdowns were too harmful and ‘herd immunity’ was Australia's only realistic option, and others who pushed for the effective ‘elimination’ of COVID-19 in Australia in the interests of longer-term health and economic benefits.31

As cases rapidly rose in Victoria and restrictions were reimposed in July 2020, the Commonwealth government rejected calls for ‘elimination’. It condemned the length and severity of Victoria's lockdown, citing the economic cost.32 The early harmony of the national cabinet gave way to fractious political bickering and sniping. But the Commonwealth's opposition eventually gave way to state leaders' ambition to keep their state COVID-free, with Australia effectively maintaining very low case number throughout the first half of 2021.

3.3.2. Transparency and data communication

Despite regular media briefings, the communication of COVID-19 case numbers has been fragmented. Each state has reported their case numbers differently. Victoria's limited data transparency (albeit improving later) suggested that there was no internal functioning information system that collected this data.33 And despite this evidence-based approach, the rationale for some restrictions such as the curfew were not adequately explained.34

The slow vaccine rollout has also been covered by a veil of secrecy. It took months into the vaccination programme for the government to publish any meaningful data on the vaccine doses to be allocated, and the rates of vaccinations. The Commonwealth also paid millions of dollars to private companies to help with the rollout – but exactly who has been paid how much and for what is shrouded in secrecy.

3.3.3. Racism/bias/ignorance

COVID-19 shines a light on the existing inequities in society. In Melbourne, it affected more people in lower socio-economic areas. To address this, the Victorian government introduced worker-support payments and test-isolation payments to eligible people to cover the period of isolation.

The Victorian government also took a particularly harsh approach to managing the virus in social housing. During the early phase of the second wave, cases linked to public housing towers resulted in the government putting 11 towers – home to thousands of people – into strict lockdown. These towers, some 20 to 30 storeys high, house many migrant communities, and in many cases, the accommodation is over-crowded. Residents received almost no warning, with police arriving within hours of the announcement to immediately enforce the new rules. Residents were not permitted to leave their apartments for five days – not even to go food shopping. An independent Ombudsman inquiry found that the lockdown ‘did not appear justified and reasonable in the circumstances, nor compatible with the right to humane treatment when deprived of liberty’.35 A more compassionate and better coordinated response may have achieved the same results.36

Australia's international border closures were also criticised as being potentially racist, firstly when they were introduced in early 2020, but more seriously when the Commonwealth banned Australian citizens returning from India in April/May 2021 – threatening five years imprisonment. While the government argued it was to manage the increased risk of the infectious Delta variant, such harsh measures imposed on its own citizens was unprecedented.

3.3.4. A slow vaccine rollout

Australia lagged behind comparable countries in its COVID vaccine rollout. By July 2021 – 5 months into its vaccine rollout – the proportion of people vaccinated put Australia last in the OECD. The main reason is that the Commonwealth government – which is responsible for the vaccination programme – botched its vaccine strategy, investing in a narrow range of vaccines, and failing to secure adequate supply. Of the four vaccines it ordered, only two were in use 5 months in, and one of them – AstraZeneca – was only recommended for people over 60 years.

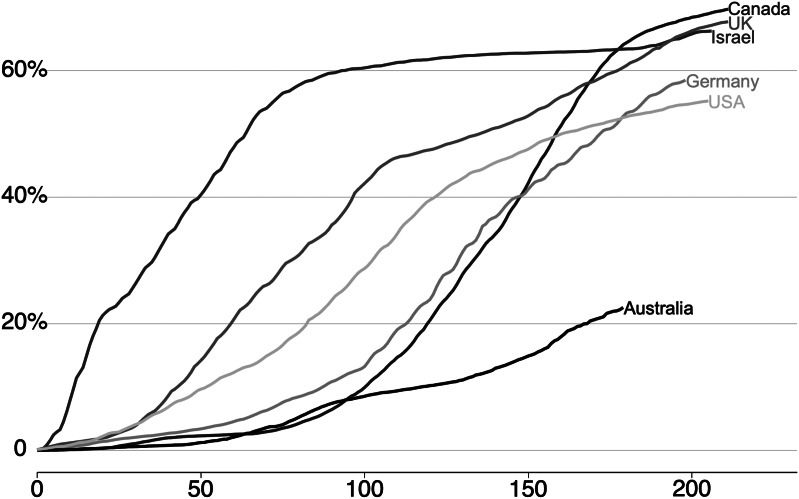

The Commonwealth also failed to demonstrate the sense of urgency for population-wide vaccination, instead initially declaring the rollout was ‘not a race’ (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

In July 2021, Australia's vaccine rollout was lagging behind comparable countries. Percentage of population that have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, days since first reported vaccination numbers, July 2021.

Source: Ritchie et al. (2020).

3.4. Looking forward

Many Australians count themselves as lucky that the country has not been ravaged by COVID-19 to date. But the crisis has not been without its challenges. As with the experience in many places, COVID-19 has exposed both the vulnerabilities and strengths in our society. Despite the Australian community's collective effort during the pandemic, enormous risks and challenges still remain, with the scars likely to be evident for decades to come.

Footnotes

Duckett et al., 2020

E.g., see: Davis and Burnie, 2020

Thompson, 2020

Coronavirus Victoria, 2020

Duckett and Crowley, 2020

Duckett and Crowley, 2020

Adekunle et al., 2020

Palmer v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2020] FCA 1221

Palmer & Anor v The State of Western Australia & Anor [2020] HCATrans 180 (6 November 2020)

Roy, 2020

RACGP, 2020

Hunt, 2020

Coroners Court, 2020

Markham et al., 2020

Finlay and Wenitong, 2020

Frydenberg, 2020

Bishop and Day, 2020

Senate Select Committee on COVID-19, 2020

NSW Government (2020), p. 32.

COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry (2020), p. 9.

So far, it has only released an interim report on what Victoria's future hotel quarantine arrangements should look like: COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry (2020).

Grout et al., 2021

Senate Select Committee on COVID-19, 2020

National Contact Tracing Review Panel, 2020

This was probably made more difficult by the under-investment in public health and public health IT by both sides of politics for decades: Ilanbey and Baker, 2020

Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council 2020

Taylor, 2020

Senate Select Committee on COVID-19, 2020

Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, 2020

This is based on a June 2020 review of 26 countries including the UK and the US: Comas-Herrera et al., 2020

Prime Minister of Australia, 2020

Duckett, 2020b

Victoria Ombudsman, 2020

Carrasco et al., 2020

References

- Adekunle A, Meehan M, Rojas-Alvarez D, Trauer J and McBryde E (2020) Delaying the COVID-19 epidemic in Australia: evaluating the effectiveness of international travel bans. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44(4), 257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J and Day I (2020) How many jobs did JobKeeper keep?. Research Discussion Papers – RDP 2020–07, pp. 1–54. Retrieved from https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2020/2020-07.html. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco S, Faleh M and Dangol N (2020) Our lives matter – Melbourne public housing residents talk about why COVID-19 hits them hard. The Conversation. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/our-lives-matter-melbourne-public-housing-residents-talk-about-why-covid-19-hits-them-hard-142901. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Herrera A, Zalakaín J, Litwin C, Hsu AT, Lemmon E, Henderson D and Fernández J-L (2020) Mortality associated with COVID-19 outbreaks in care homes: early international evidence. International Long-term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus Victoria (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19) roadmap for reopening. Victorian Government. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/coronavirus-covid-19-restrictions-roadmaps. [Google Scholar]

- Coroners Court (2020) Monthly Suicide Data Report. Retrieved from www.coronerscourt.vic.gov.au.

- COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry (2020) COVID-19 Hotel Quarantine Inquiry Interim Report and Recommendations. Retrieved from https://www.quarantineinquiry.vic.gov.au/reports.

- Davis J and Burnie R (2020) NSW-Victoria border restrictions putting lives at risk, doctors say in open letter to NSW government. The ABC. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-24/nsw-victoria-border-restrictions-putting-lives-at-risk-doctors/12487874. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S (2020a) COVID-19: there are only two options from here. One is more deadly. Australian Financial Review. Retrieved from https://grattan.edu.au/news/covid-19-there-are-only-two-options-from-here-one-is-more-deadly/. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S (2020b) Victoria's daily COVID-19 reporting is hopelessly inadequate. The Age. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/victoria-s-daily-covid-19-reporting-is-hopelessly-inadequate-20200807-p55jli.html. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S (2020c) Victoria Now has a good roadmap out of COVID-19 restrictions. New south wales should emulate it. The Conversation. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/victoria-now-has-a-good-roadmap-out-of-covid-19-restrictions-new-south-wales-should-emulate-it-145393. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S (2020d) Dan's plan is mostly right … and partly wrong. The Age. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/dan-s-plan-is-mostly-right-and-partly-wrong-20200908-p55tit.html. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S and Crowley T (2020) Finally at zero new cases, Victoria is on top of the world after unprecedented lockdown effort. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/finally-at-zero-new-cases-victoria-is-on-top-of-the-world-after-unprecedented-lockdown-effort-148808. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S and Mackey W (2020) Go for Zero: How Australia can get to Zero COVID-19 Cases. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S, Mackey W, Stobart A and Swerissen H (2020) Coming out of COVID-19 Lockdown: The Next Steps for Australian Health Care. Melbourne: Grattan Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay S and Wenitong M (2020) Aboriginal community controlled health organisations are taking a leading role in COVID-19 health communication. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44, 251–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydenberg J (2020) Rebuilding the Economy and Securing Australia's Future. Canberra: Treasury. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/josh-frydenberg-2018/media-releases/rebuilding-economy-and-securing-australias-future. [Google Scholar]

- Grout L, Katar A, Ouakrim DA, Summers JA, Kvalsvig A, Baker MG, Blakely T and Wilson N (2021) Estimating the failure risk of quarantine systems for preventing COVID-19 outbreaks in Australia and New Zealand. Preprint. 10.1101/2021.02.17.21251946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt G (2020) Unprecedented mental health support for Australians during the pandemic. Australian Government. Retrieved from https://www.greghunt.com.au/unprecedented-mental-health-support-for-australians-during-the-pandemic/. [Google Scholar]

- Ilanbey S and Baker R (2020) Coronavirus Victoria: Andrews government warned multiple times Victoria's public health team was the worst resourced in the country. The Age. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.theage.com.au/politics/victoria/top-bureaucrats-warned-a-year-ago-victoria-s-key-public-health-team-was-starved-of-money-and-staff-20200729-p55ggh.html?fbclid=IwAR03ZuXxUNk23yLpoL3tKLQ_tyL1DDVsNzyGWFi7kFJgeQfqeIVDBEvbY0c. [Google Scholar]

- Markham F, Smith D and Morphy F (2020) Indigenous Australians and the COVID-19 crisis: perspectives on public policy. ANU Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR). 10.25911/5e8702ec1fba2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Contact Tracing Review Panel (2020) National Contact Tracing Review. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-contact-tracing-review. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government (2020) Special Commission of Inquiry: Ruby Princess. Sydney: NSW Government. Retrieved from https://www.nsw.gov.au/covid-19/special-commission-of-inquiry-ruby-princess. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council (2020) Inquiry Into the Victorian Government's COVID-19 Contact Tracing System and Testing Regime. Melbourne: Victorian Parliament. Retrieved from https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/lsic-lc/article/4574. [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister of Australia (2020) Initial Commonwealth Response to Victorian Roadmap. Canberra: Australian Government. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from https://www.pm.gov.au/media/initial-commonwealth-response-victorian-roadmap. [Google Scholar]

- RACGP (2020) RACGP Survey reveals strong take up of telehealth but face to face consultations still available. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.racgp.org.au/gp-news/media-releases/2020-media-releases/may-2020/racgp-survey-reveals-strong-take-up-of-telehealth. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, Mathieu E, Hasell J, Macdonald B, Giattino C, Appel C, Rodés-Guirao L and Roser M (2020) Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- Roy Morgan (2020) Victorians in strong support of most Stage 4 restrictions, Finding No. 8503. Roy Morgan. Retrieved November 24, 2020, from http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/8503-views-on-stage-4-restrictions-in-victoria-august-27-2020-202008260908. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2020) Aged Care and COVID-19: A Special Report Royal Commission Into Aged Care Quality and Safety. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved from https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aged-care-and-covid-19-a-special-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 (2020) First interim report. Retrieved from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/COVID-19/COVID19/Interim_Report.

- Taylor J (2020) How did the covidsafe app go from being vital to almost irrelevant? The Guardian. Retrieved May 30, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/24/how-did-the-covidsafe-app-go-from-being-vital-to-almost-irrelevant. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson B (2020) WA Reveals $5.5b stimulus as borders stay closed. Financial Review. Retrieved from https://www.afr.com/politics/wa-reveals-5-5b-stimulus-as-borders-stay-closed-20200726-p55fk9. [Google Scholar]

- Victoria Ombudsman (2020) Investigation Into the Detention and Treatment of Public Housing Residents Arising From a COVID-19 ‘Hard Lockdown’ in July 2020. Melbourne: Victoria Ombudsman. [Google Scholar]