Abstract

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) results from ascension of sexually transmitted pathogens from the lower genital tract to the uterus and/or fallopian tubes in women, with potential spread to neighboring pelvic organs. Patients may present acutely with lower abdominal or pelvic pain and pelvic organ tenderness. Many have subtle symptoms or are asymptomatic and present later with tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, or chronic pelvic pain. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the 2 most commonly recognized PID pathogens. Their ability to survive within host epithelial cells and neutrophils highlights a need for T-cell–mediated production of interferon γ in protection. Data indicate that for both pathogens, antibody can accelerate clearance by enhancing opsonophagocytosis and bacterial killing when interferon γ is present. A study of women with N. gonorrhoeae– and/or C. trachomatis–induced PID with histologic endometritis revealed activation of myeloid cell, cell death, and innate inflammatory pathways in conjunction with dampening of T-cell activation pathways. These findings are supported by multiple studies in mouse models of monoinfection with N. gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia spp. Both pathogens exert multiple mechanisms of immune evasion that benefit themselves and each other at the expense of the host. However, similarities in host immune mechanisms that defend against these 2 bacterial pathogens instill optimism for the prospects of a combined vaccine for prevention of PID and infections in both women and men.

Keywords: Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometritis, T cells, cytokines, antibody

Ascension of sexually transmitted pathogens from the endocervix to the uterus and/or fallopian tubes can result in pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Symptomatic PID is characterized by lower abdominal pain, pelvic organ tenderness, and evidence of cervicovaginal inflammation. Symptoms may present acutely over several days, or indolently, over weeks to months. Potentially devastating long-term sequelae include tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain. Since most women with tubal factor infertility have no history of symptomatic PID, damage to the fallopian tubes may occur with subclinical infections, leading to ongoing recommendations for periodic screening of sexually active women for infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis, the 2 most commonly recognized PID pathogens.

N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are gram-negative pathogens that survive extra- and intracellularly. N. gonorrhoeae microcolony formation occurs on epithelial cells soon after infection, and after a period of replication, gonococci attached to epithelial cells can be engulfed and survive intracellularly. Chlamydia are transmitted during sex as compact elementary bodies (EBs), which rapidly invade epithelial cells via a panoply of mechanisms. On uptake, EBs differentiate into metabolically active, replicating reticulate bodies within a protective fused vacuole or inclusion. This review focuses on the immunopathogenesis of PID due to C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae that exert parallel mechanisms of immune evasion at the expense of the host.

IMMUNOPATHOGENESIS

Gonorrhea/Chlamydia Coinfection—Double Whammy

Advances in high-throughput genomic technologies have made it possible to define transcriptional networks correlated with disease (Figure 1). Blood messenger RNA (mRNA) network analysis investigated the pathogenic mechanisms underlying PID in a cohort of women enrolled in a clinical trial comparing antibiotic treatment regimens [1]. Women with clinical PID and histologic chronic endometritis due to N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis exhibited a blood transcriptional profile that distinguished them from uninfected women with lower abdominal pain who had normal endometrial histologic findings, and from asymptomatic women with normal endometrial histologic findings and with N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis infection limited to their cervix [2].

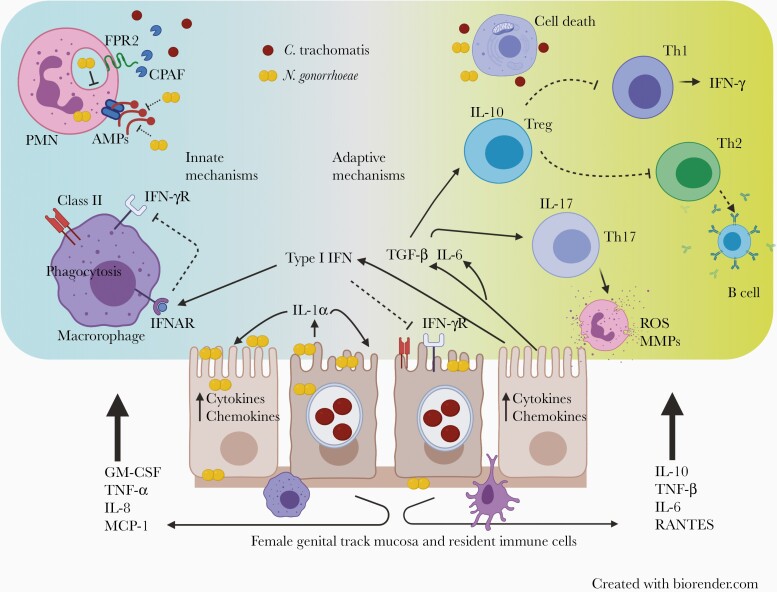

Figure 1.

Immune evasion and pathogenic mechanisms of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. Both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis can live extracellularly and inside genital tract epithelial cells. C. trachomatis replicates inside a protective inclusion within host epithelial cells. N. gonorrhoeae invades epithelial cells and can spread beyond the mucosa and disseminate. Infected host epithelial cells and resident innate immune cells produce chemokines and cytokines that drive influx of inflammatory leukocytes including tissue-damaging polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs). Innate immune response evasion involves the following: N. gonorrhoeae delays PMN phagolysosome fusion, and secretes factors that disable antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). C. trachomatis evades PMN killing through production of chlamydial protease activating factor (CPAF) which cleaves neutrophil formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2), disabling production of neutrophil extracellular traps, degranulation, and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae induce production of type I interferon (IFN) which inhibits IFN-γ–mediated activation of phagocytes. Both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis induce production of interleukin 1α (IL-1α) which promotes host cell death and hyperactivation of PMNs. In adaptive immune response evasion, C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae–induced type I IFN limits IFN-γ–mediated up-regulation of class II major histocompatibility complex molecules necessary for effective CD4 T-cell recognition of infected host epithelial cells. N. gonorrhoeae induces production of transforming growth factor (TGF) β, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and interleukin 10 (IL-10); TGF-β and IL-6 drive induction of T-helper (Th) 17 cells which recruit ineffective PMNs that release matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) and ROS. TGF-β drives induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which combine with IL-10 to dampen both Th1 and Th2 responses. Ongoing infection and chronic T-cell antigen stimulation leads to dysfunctional T-cell metabolism. Inhibition of T-cell mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation up-regulates genes linked to exhaustion and cell death, perpetuating infection and compromising T-cell memory. Abbreviations: GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN-γR, IFN-γ receptor; IFNAR, interferon alpha receptor; IL-8, interleukin 8; IL-17, interleukin 17; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein ; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

The N. gonorrhoeae– and/or C. trachomatis–induced endometritis transcriptional signature was characterized by overexpression of myeloid and cell death genes and suppression of transcripts involved in T-cell signaling, protein synthesis, and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Coinfection led to greater activation of cell death pathways and worse suppression of adaptive immune response genes. Women with PID solely infected with C. trachomatis were distinguished from coinfected women by their elevated expression of genes in type I and type II interferon (IFN) response pathways. The detection of significantly reduced expression of genes associated with T-cell signaling and proliferation agree with detection of, at best, short-term, partial immunity in persons that have sustained chlamydial infection, and the absence of immune protection after N. gonorrhoeae infection.

The biological significance of these human data is supported by multiple decades’ worth of mechanistic studies using mice infected with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae. Protective T-helper (Th) 1 and Th2 responses are inhibited in mice infected with N. gonorrhoeae through induction of transforming growth factor (TGF) β and interleukin 10 (IL-10) [3]. Chlamydial infection drives type I IFN responses in mice that inhibit protective Th1 responses [4]. A derogatory role for IL-10 during chlamydial infection is evidenced by a marked reduction in chlamydial burden and disease in IL-10–deficient mice, an accelerated and prolonged protective Th1 response when IL-10–deficient dendritic cells (DCs) fed chlamydia are inoculated into mice [5], and vaccine studies indicating that killed C. trachomatis taken up by CD103+ DCs leads to IL-10 driven tolerogenic regulatory T cells (Tregs) and enhanced infection in challenged mice [6]. Finally, exhaustion of C. trachomatis–specific CD8 T cells has been shown to limit their ability to effectively contribute to immune protection in C. trachomatis–infected mice [7].

Innate Responses Drive Reproductive Tract Damage

Women with C. trachomatis– and/or N. gonorrhoeae–induced endometritis exhibited up-regulation of genes for multiple Toll-like receptors, neutrophil and monocyte activation, migration, adhesion, cell death pathways, and IL-1– and inflammasome related genes [8]. Increased transcription for interleukin 17RA occurred in coinfected women, coincident with neutrophil-inducing chemokines. Increased activation of cell death and tissue damaging pathways in coinfected women may explain the enhanced rates of infertility that were reported in women with PID during the 1960s and 1970s, when N. gonorrhoeae prevalence peaked [9].

In vitro and murine studies of C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae reveal activation of similar inflammatory pathways. Mucosal cell production of chemokines drives neutrophil influx, but N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis possess potent mechanisms to inhibit neutrophil killing. The multiple transferable resistance efflux pump of N. gonorrhoeae releases factors that defend against antimicrobial peptides [10], and N. gonorrhoeae phagosomes delay fusion with neutrophil primary granules [11]. Chlamydial protease activation factor is produced by C. trachomatis in high abundance and released into the inclusion. With lysis of the host cell, chlamydial protease activation factor is free to cleave neutrophil formyl peptide receptor 2, which paralyzes formation of neutrophil extracellular traps and suppresses the oxidative burst [12]. Outer membrane vesicles from N. gonorrhoeae induce cellular pyronecrosis and interleukin 1β secretion [13], while IL-1α released from C. trachomatis–infected fallopian tube cells causes direct cellular damage [14]. Using the mouse model of Chlamydia muridarum genital infection, Gyorke et al in 2020 confirmed a key role for interleukin 1α (IL-1α), released during inflammatory cell death, in pathogenesis [15]. Significantly decreased neutrophil recruitment was detected in the oviducts of Il1a–/– mice on multiple days during infection, and reduced neutrophil infiltrates and hydrosalpinx were observed on resolution of infection. Furthermore, antibody-mediated depletion of IL-1α prevented infection induced oviduct damage, demonstrating IL-1α as an important therapeutic target.

During murine genital tract gonococcal infection, the local response is dominated by interleukin 17, with consequent recruitment of neutrophils [16]. During murine chlamydial infection, interleukin 17A drives neutrophil influx, is expendable for clearance [17], and enhances disease [18]. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that neutrophil matrix metalloprotease 9 is a major contributor to oviduct disease [19].

Type I IFN Responses Favorable to Pathogens Over Host

Women with chronic endometritis infected only with C. trachomatis had significantly increased expression of type I (IFN-α/β) and type II (IFN-γ) genes [8]. IFN-γ inhibits chlamydial growth and replication and activates phagocytic cells for bacterial killing. Elevated type I IFN-induced chemokines were detected in endometrial tissues and cervical secretions of C. trachomatis–infected women with PID and chronic endometritis, linking the type I IFN response to poor C. trachomatis control. Despite the lack of detection of a systemic type I IFN response in women coinfected with N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis, IFN-β mRNA was observed in their endometrial tissues. Hyperactivation of cell death pathways in coinfected women may have prevented the detection of type I IFN responses in their peripheral blood [8].

These results complement previously published findings from the C. muridarum mouse model, where mice genetically deficient in the receptor for type 1 IFNs (IFNAR−/−) demonstrated significantly less chlamydial shedding, a shorter infection, and less oviduct disease, compared with wild-type controls. The protection observed in IFNAR−/− mice was associated with an earlier and more robust CD4 T-cell response [4]. High and prolonged levels of type I IFN decrease the expression of IFNGR and inhibit IFN-γ–induced expression of major histocompatibility complex class II [20, 21], which is essential for CD4 T-cell–mediated control of chlamydial infection. A pathogenic role for IFN-β mRNA in endometrial tissues of N. gonorrhoeae/C. trachomatis–coinfected women is supported by a transcriptional analysis of murine uterine responses after gonococcal infection, where type 1 IFN induction was associated with increased disease in mice [22].

Blunted Adaptive T-Cell Immunity in Women With N. gonorrhoeae– and/or CT-induced Chronic Endometritis

In women with C. trachomatis– and/or N. gonorrhoeae–induced endometritis, genes encoding T-cell coreceptors and kinases involved in T-cell signaling and those involved in protein synthesis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation were decreased compared with uninfected women and women with cervically limited infection [8]. Memory T-cell responses are important for protection against C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae but are short-lived after natural infection, permitting high rates of reinfection on repeat exposure.

In vitro and mouse models have shown that N. gonorrhoeae impairs induction of adaptive immunity by multiple mechanisms. These include apoptosis of antigen-presenting cells [13], inhibition of dendritic cell–mediated T-cell proliferation [23], down-regulation of CD4 T-cell and B-cell proliferation by binding inhibitory CEACAM1 [24, 25], and induction of IL-10 and TGF-β, that drive induction of immunosuppressive Tregs [3]. Gonococcal infection was found to be a leading risk factor for recurrent C. trachomatis infection in a cohort of sexually active women [26], indicating that N. gonorrhoeae inhibits development of protective responses to C. trachomatis.

Most women and men with N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis infection are asymptomatic, and infections are primarily detected through screening of at-risk individuals. Thus, many infections are likely chronic, which could lead to prolonged antigen stimulation of T cells. Inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in activated T cells is sufficient to suppress proliferation and up-regulate genes linked to T-cell exhaustion [27]. Chronic antigen stimulation leading to dysfunctional T-cell metabolism may be a marker for disease, or even play a role in progression of infection to PID and chronic endometritis. Down-regulation of T cells, protein synthesis, or mitochondrial respiration genes was not detected in blood transcriptional profiles in women with C. trachomatis–induced PID and acute endometritis (detection of neutrophils in endometrial surface epithelium), but increased transcription of type I IFN response genes was observed. This suggests that C. trachomatis induces early activation of type I IFN, which could then hinder CD4 Th1 effector mechanisms, leading to poor chlamydial control, and worse disease.

Ineffective and Effective Mucosal Cytokines Against C. trachomatis

Analysis of cytokines in cervical secretions of C. trachomatis–infected women who were evaluated for endometrial ascension and followed up at intervals for incident infection over 12 months revealed increased levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, interleukin 17A, CXCL9, and CXCL10 were associated with enhanced risk for endometrial infection. All of these proteins promote neutrophil influx and activation. In contrast, interleukin 15 (IL-15), interleukin 16, and CXCL14 levels were associated with decreased risk of endometrial infection [28]. IL-15 promotes T-cell survival [29] and effector function by up-regulating IFN-γ production [30]. Interleukin 16 is a potent chemoattractant for CD4 T cells and can prime Th1 cells for interleukin 2 and IL-15 responsiveness [31]. CXCL14 is chemotactic for dendritic cells [32] and augments Th1 induction via enhancement of Toll-like receptor 9 stimulation [33]. These results are consistent with a role for inflammatory neutrophil-recruiting cytokines in immunopathology and for cytokines involved in T-cell polarization and activation in protection against chlamydial infection.

Association of Cytokines With Altered Risk of Reinfection

Chemokines induced by type I IFNs, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, were associated with increased risk of reinfection. Increased levels of a B-cell growth factor, IL-14, were also associated with increased risk of reinfection and may represent induction of a nonprotective humoral response against C. trachomatis. Vascular endothelial growth factor and Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt-3L) were associated with decreased risk. Vascular endothelial growth factor has been shown to enhance IFN-γ production and chemotaxis of memory CD4 T cells [34]. Flt-3L is a dendritic cell growth factor important for IL-12 and IFN-γ production [35]. Thus, mucosal detection of cytokines involved in type I IFN, Th17, and humoral responses were associated with susceptibility to C. trachomatis, whereas those involved in Th1 polarization, recruitment, and activation were associated with protection against ascension and reinfection. These data are consistent with longitudinal analyses of highly exposed women that associated a reduced risk of reinfection with C. trachomatis–specific CD4 T-cell IFN-γ responses [36], but not serum anti-C. trachomatis immunoglobulin (Ig) G titers [37].

Antibody is Insufficient for Protection

Although N. gonorrhoeae–specific antibodies that inhibit epithelial adherence are generated within the genital tract, they are short lived [38]. Infection occurs despite detection of anti–N. gonorrhoeae antibodies. Anti-reduction modifiable protein (Rmp) can block bactericidal activity of other N. gonorrhoeae–directed antibodies and prevent protection [39]. Coupled with suppression of Th1 and Th2 responses and extensive antigenic variation by N. gonorrhoeae, immune memory after natural infection is limited [39].

High titers of anti–C. trachomatis antibodies are associated with enhanced disease, suggesting antibody titers reflect repeated and/or prolonged chlamydia exposure and do not predict protective immunity [40]. This conclusion is supported by data from women highly exposed to C. trachomatis who were examined for endometrial infection and followed for incident infection over a year [37]. Among women uninfected at enrollment, each unit of serum or cervical anti-EB IgG was associated with a 3.6‐fold or 22.6‐fold increased risk of reinfection, respectively. For women infected at enrollment, antibody levels failed to predict detection of C. trachomatis endometrial infection, although serum and cervical anti-EB IgG and cervical IgA levels were inversely correlated with cervical C. trachomatis burden, and lower burden was associated with reduced ascension. Causal mediation analysis revealed that antibody-mediated reduction of cervical bacterial burden is insufficient to prevent ascension. Thus, it is likely that high levels of anti‐EB antibodies reflect poor protective T‐cell immunity and serves best as a marker of increased risk or susceptibility.

Overcoming Immune Evasion Through Vaccination

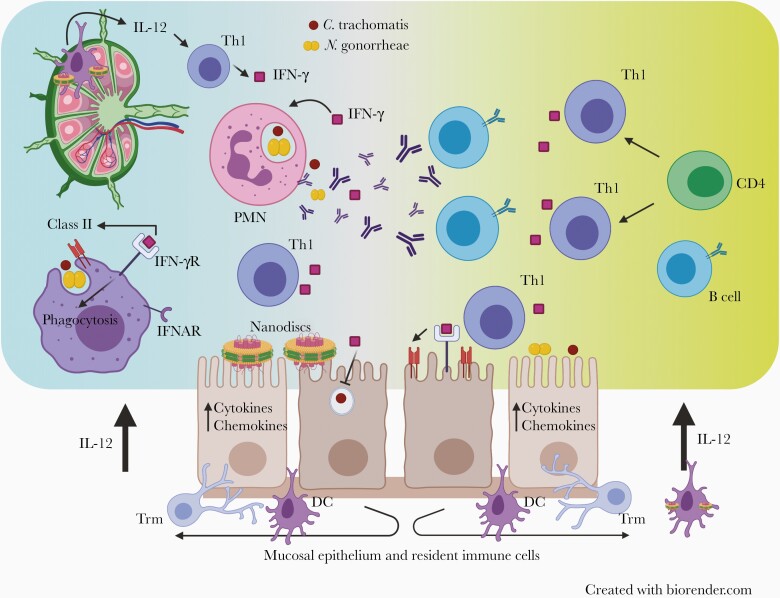

These mechanisms of immune evasion can be overcome by vaccination using routes and adjuvants that elicit a robust mucosal Th1 response that can cooperate with pathogen-specific antibody to promote protection. Protection from N. gonorrhoeae elicited in mice immunized with gonococcal outer membrane vesicles and microencapsulated IL-12 depended on induction of both Th1-driven IFN-γ production and anti–N. gonorrhoeae antibodies [41]. The mechanisms for IFN-γ–mediated inhibition of N. gonorrhoeae remain to be defined. Antibody-mediated protection against chlamydia is primarily mediated by enhanced opsonophagocytosis and degradation of chlamydial EBs that requires IFN-γ produced primarily by C. trachomatis–specific CD4 Th1 cells [42] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overcoming Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis immune evasion through vaccination. Delivery of immunostimulatory nanodiscs containing N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis antigens and T-helper (Th) 1–inducing adjuvants via a mucosal route stimulates the induction of CD4 Th1 cells that produce interferon (IFN) γ and provide help to antibody-producing B cells. The combined presence of antibody and IFN-γ will enhance opsonophagocytosis and killing of both C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae. IFN-γ released from Th1 cells will decrease growth and replication of C. trachomatis within host epithelial cells and inhibit N. gonorrhoeae through as-yet undefined mechanisms. Abbreviations: IFN-γR, IFN-γ receptor; IFNAR, interferon-alpha receptor; IL-12, interleukin 12; PMN, polymorphonuclear cell; Trm, T resident memory.

The potential for detrimental adaptive T-cell responses during chlamydial infection is apparent in studies of IFN-γ–deficient mice, where hyperactivation of Th17 cells and massive neutrophilic exudates are observed [43]. A role for CD8 T cells in disease development is suggested by murine studies detecting reduced levels of oviduct damage in mice deficient for CD8 T cells, despite normal rates of bacterial clearance [44]. Adoptive transfer of wild-type, but not TNF-α–deficient CD8 T cells into CD8-deficient mice resulted in oviduct disease equal to that observed in infected wild-type mice, suggesting TNF-α is a key pathogenic molecule. The role of CD8 T cells in pathogenesis during human chlamydial genital infection remains to be investigated.

Data from humans and animals indicate that repeated C. trachomatis infection can lead to worse oviduct disease. Determination of which immune responses associated with repeated infection promote disease in women has been challenging, because histologic studies of reproductive tissues reveal neutrophils, lymphocyte aggregates, monocytes, and plasma cells [45]. An attenuated plasmid-deficient C. muridarum strain, CM3.1—which causes burden and course of infection similar to those in wild-type C. muridarum, but which induces less neutrophilic inflammation and fails to induce chronic oviduct disease—was used to investigate for tissue-damaging T-cell responses on challenge. Primary infection with CM3.1 did not induce sterilizing immunity but protected mice from disease after challenge with virulent C. muridarum. Oviduct infection levels were markedly reduced after challenge, as were the total numbers of leukocytes. Notably, frequencies of both CD4 and CD8 T cells were significantly increased compared with primary infection, although neutrophils were reduced. Similar reductions in neutrophils and oviduct damage and enhanced T-cell responses were observed in mice after multiple infections with virulent C. muridarum abbreviated by antibiotic treatment [46]. These data suggest that protective immunity can be induced by repeated infections that are prevented from ascending to the oviducts.

A cautionary tale comes from a landmark murine vaccine study [6], where it was shown that direct inoculation of killed C. trachomatis into the uterus of mice generated tolerogenic C. trachomatis–specific Tregs, resulting in increased bacterial burden on C. trachomatis challenge. In contrast, uterine inoculation with killed C. trachomatis in charge-switching nanoparticles coupled to a Toll-like receptor 7/8 agonist resulted in induction of a sustained protective C. trachomatis–specific Th1 response. The opposing T-cell responses were due to differential uptake of antigen by either tolerogenic CD103+ DCs that produced IL-10 or immunostimulatory CD103− DCs that produced IL-12. The induction of the detrimental Treg response required uterine exposure because intranasal and subcutaneous inoculations with killed C. trachomatis failed to enhance susceptibility. This study also showed that systemic immunization failed to protect and did not induce uterine resident memory T cells as observed with mucosal routes. Thus, adjuvants and routes of immunization that avoid the induction of C. trachomatis–specific Tregs will be required to prevent risk of heightened infection and disease in vaccinated women who become sexually exposed to C. trachomatis.

Similarities in host protective immune mechanisms for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis instill optimism for the prospects of a combined vaccine to aid in prevention of PID and tubal factor infertility in women and of C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae infection in men and women. Blockade of TGF-β and IL-10 in the murine N. gonorrhoeae model reverses N. gonorrhoeae–mediated suppression of Th1 and Th2 responses and promotes protective immunity [3]. Mucosal delivery to mice of N. gonorrhoeae outer membrane vesicles combined with the Th1-promoting cytokine, IL-12, drives protection [41]. Finally, data from countries conducting mass vaccination campaigns against N. meningitidis serogroup B using immunogenic outer membrane vesicle–based vaccines indicate cross-species protection against N. gonorrhoeae infections [47, 48]. Correlates of N. gonorrhoeae immunity have yet to be determined, but data support involvement of both Th1 and Th2 responses. Multiple candidate N. gonorrhoeae antigens are being tested in humanized mice developed based on data regarding human cellular receptors required for infections.

Murine studies support mucosal delivery of chlamydial subunit vaccines combined with Th1-inducing adjuvants can induce protection from disease [49, 50]. The first-in-human phase 1 C. trachomatis vaccine trial using recombinant major outer membrane protein peptomers combined with a cationic liposome and an immunomodulator delivered systemically and boosted mucosally was safe and resulted in robust Th1 and antibody responses in recipients [51].

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis induce immune evasion mechanisms that promote their individual survival and benefit the alternate pathogen. Their ability to survive and grow intracellularly highlights a need for cell-mediated immunity, with studies indicating an importance for CD4 Th1 cells in protection. Antibody can enhance their opsonophagocytosis and killing when IFN-γ is present. Unfortunately, N. gonorrhoeae and/or C. trachomatis activation of cell death and type I IFN pathways dampen protective Th1 and Th2 responses. Ongoing infection and chronic T-cell antigen stimulation leads to dysfunctional T-cell metabolism and exhaustion, compromising T-cell memory. These immune evasion mechanisms can be overcome with vaccines that deliver antigens with Th1-inducing adjuvants. Similarities in host immune mechanisms that defend against these pathogens instill optimism for the prospects of a combined vaccine that would be advantageous for ease of administration and conservation of healthcare resources.

Note

Financial support. This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Allergy, Immunology and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, R01 AI119164 and U19 AI144181.

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Wiesenfeld HC, Meyn LA, Darville T, Macio IS, Hillier SL. A randomized controlled trial of ceftriaxone and doxycycline, with or without metronidazole, for the treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease. Clin Infect Dis doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa101. Published 13 February 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zheng X, O’Connell CM, Zhong W, et al. Gene expression signatures can aid diagnosis of sexually transmitted infection-induced endometritis in women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018; 8:307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Liu W, Russell MW. Suppression of host adaptive immune responses by Neisseria gonorrhoeae: role of interleukin 10 and type 1 regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol 2014; 7:165–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagarajan UM, Prantner D, Sikes JD, et al. Type I interferon signaling exacerbates Chlamydia muridarum genital infection in a murine model. Infect Immun 2008; 76:4642–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Igietseme JU, Ananaba GA, Bolier J, et al. Suppression of endogenous IL-10 gene expression in dendritic cells enhances antigen presentation for specific Th1 induction: potential for cellular vaccine development. J Immunol 2000; 164:4212–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stary G, Olive A, Radovic-Moreno AF, et al. A mucosal vaccine against Chlamydia trachomatis generates two waves of protective memory T cells. Science 2015; 348:aaa8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fankhauser SC, Starnbach MN. PD-L1 limits the mucosal CD8+ T cell response to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol 2014; 192:1079–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng X, O’Connell CM, Zhong W, et al. Discovery of blood transcriptional endotypes in women with pelvic inflammatory disease. J Immunol 2018; 200:2941–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weström L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility: a cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19:185–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handing JW, Ragland SA, Bharathan UV, Criss AK. The MtrCDE efflux pump contributes to survival of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from human neutrophils and their antimicrobial components. Front Microbiol 2018; 9:2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson MB, Criss AK. Neisseria gonorrhoeae phagosomes delay fusion with primary granules to enhance bacterial survival inside human neutrophils. Cell Microbiol 2013; 15:1323–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajeeve K, Das S, Prusty BK, Rudel T. Chlamydia trachomatis paralyses neutrophils to evade the host innate immune response. Nat Microbiol 2018; 3:824–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan JA, Gao X, Huang MT, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae activates the proteinase cathepsin B to mediate the signaling activities of the NLRP3 and ASC-containing inflammasome. J Immunol 2009; 182:6460–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hvid M, Baczynska A, Deleuran B, et al. Interleukin-1 is the initiator of fallopian tube destruction during Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Cell Microbiol 2007; 9:2795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gyorke CE, Kollipara A, Allen J 4th, et al. IL-1α is essential for oviduct pathology during genital chlamydial infection in mice. J Immunol 2020; 205:3037–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feinen B, Jerse AE, Gaffen SL, Russell MW. Critical role of Th17 responses in a murine model of Neisseria gonorrhoeae genital infection. Mucosal Immunol 2010; 3:312–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frazer LC, Scurlock AM, Zurenski MA, et al. IL-23 induces IL-22 and IL-17 production in response to Chlamydia muridarum genital tract infection, but the absence of these cytokines does not influence disease pathogenesis. Am J Reprod Immunol 2013; 70:472–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrew DW, Cochrane M, Schripsema JH, et al. The duration of Chlamydia muridarum genital tract infection and associated chronic pathological changes are reduced in IL-17 knockout mice but protection is not increased further by immunization. PLoS One 2013; 8:e76664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imtiaz MT, Distelhorst JT, Schripsema JH, et al. A role for matrix metalloproteinase-9 in pathogenesis of urogenital Chlamydia muridarum infection in mice. Microbes Infect 2007; 9:1561–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rayamajhi M, Humann J, Penheiter K, Andreasen K, Lenz LL. Induction of IFN-αβ enables Listeria monocytogenes to suppress macrophage activation by IFN-γ. J Exp Med 2010; 207:327–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinchieri G. Type I interferon: friend or foe? J Exp Med 2010; 207:2053–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francis IP, Islam EA, Gower AC, Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb YB, Gray-Owen SD, Wetzler LM. Murine host response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae upper genital tract infection reveals a common transcriptional signature, plus distinct inflammatory responses that vary between reproductive cycle phases. BMC Genomics 2018; 19:627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu W, Ventevogel MS, Knilans KJ, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae suppresses dendritic cell-induced, antigen-dependent CD4 T cell proliferation. PLoS One 2012; 7:e41260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boulton IC, Gray-Owen SD. Neisserial binding to CEACAM1 arrests the activation and proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 2002; 3:229–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantelic M, Kim YJ, Bolland S, Chen I, Shively J, Chen T. Neisseria gonorrhoeae kills carcinoembryonic antigen-related cellular adhesion molecule 1 (CD66a)-expressing human B cells and inhibits antibody production. Infect Immun 2005; 73:4171–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell AN, Zheng X, O’Connell CM, et al. Analysis of factors driving incident and ascending infection and the role of serum antibody in Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:523–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vardhana SA, Hwee MA, Berisa M, et al. Impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation limits the self-renewal of T cells exposed to persistent antigen. Nat Immunol 2020; 21:1022–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poston TB, Lee DE, Darville T, et al. Cervical cytokines associated with Chlamydia trachomatis susceptibility and protection. J Infect Dis 2019; 220:330–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purton JF, Tan JT, Rubinstein MP, Kim DM, Sprent J, Surh CD. Antiviral CD4+ memory T cells are IL-15 dependent. J Exp Med 2007; 204:951–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borger P, Kauffman HF, Postma DS, Esselink MT, Vellenga E. Interleukin-15 differentially enhances the expression of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in activated human (CD4+) T lymphocytes. Immunology 1999; 96:207–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin XJ, Shi HZ, Huang ZX, Kang LF, Mo WN, Wu C. Interleukin-16 in tuberculous and malignant pleural effusions. Eur Respir J 2005; 25:605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salogni L, Musso T, Bosisio D, et al. Activin A induces dendritic cell migration through the polarized release of CXC chemokine ligands 12 and 14. Blood 2009; 113:5848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanegashima K, Takahashi R, Nuriya H, et al. CXCL14 acts as a specific carrier of CpG DNA into dendritic cells and activates Toll-like receptor 9-mediated adaptive immunity. EBioMedicine 2017; 24:247–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basu A, Hoerning A, Datta D, et al. Cutting edge: vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated signaling in human CD45RO+ CD4+ T cells promotes Akt and ERK activation and costimulates IFN-γ production. J Immunol 2010; 184:545–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupont CD, Harms Pritchard G, Hidano S, et al. Flt3 ligand is essential for survival and protective immune responses during toxoplasmosis. J Immunol 2015; 195:4369–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell AN, Zheng X, O’Connell CM, et al. Identification of Chlamydia trachomatis antigens recognized by T cells from highly exposed women who limit or resist genital tract infection. J Infect Dis 2016; 214:1884–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darville T, Albritton HL, Zhong W, et al. Anti-chlamydia IgG and IgA are insufficient to prevent endometrial chlamydia infection in women, and increased anti-chlamydia IgG is associated with enhanced risk for incident infection. Am J Reprod Immunol 2019; 81:e13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tramont EC, Ciak J, Boslego J, McChesney DG, Brinton CC, Zollinger W. Antigenic specificity of antibodies in vaginal secretions during infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Infect Dis 1980; 142:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovett A, Duncan JA. Human immune responses and the natural history of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection. Fron Immunol 2019; 9:3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batteiger BE, Xu F, Johnson RE, Rekart ML. Protective immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection: evidence from human studies. J Infect Dis 2010; 201(suppl 2):S178–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Y, Hammer LA, Liu W, et al. Experimental vaccine induces Th1-driven immune responses and resistance to Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in a murine model. Mucosal Immunol 2017; 10:1594–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naglak EK, Morrison SG, Morrison RP. IFNγ is required for optimal antibody-mediated immunity against genital Chlamydia infection. Infect Immun 2016; 84:3232–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scurlock AM, Frazer LC, Andrews CW Jr, et al. Interleukin-17 contributes to generation of Th1 immunity and neutrophil recruitment during Chlamydia muridarum genital tract infection but is not required for macrophage influx or normal resolution of infection. Infect Immun 2011; 79:1349–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murthy AK, Li W, Chaganty BK, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha production from CD8+ T cells mediates oviduct pathological sequelae following primary genital Chlamydia muridarum infection. Infect Immun 2011; 79:2928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiviat NB, Paavonen JA, Wølner-Hanssen P, et al. Histopathology of endocervical infection caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, herpes simplex virus, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Hum Pathol 1990; 21:831–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riley MM, Zurenski MA, Frazer LC, et al. The recall response induced by genital challenge with Chlamydia muridarum protects the oviduct from pathology but not from reinfection. Infect Immun 2012; 80:2194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whelan J, Kløvstad H, Haugen IL, Holle MR, Storsaeter J. Ecologic study of meningococcal B Vaccine and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection, Norway. Emerg Infect Dis 2016; 22:1137–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petousis-Harris H, Paynter J, Morgan J, et al. Effectiveness of a group B outer membrane vesicle meningococcal vaccine against gonorrhoea in New Zealand: a retrospective case-control study. Lancet 2017; 390:1603–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pal S, Davis HL, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Immunization with the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis major outer membrane protein by use of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant induces a protective immune response against an intranasal chlamydial challenge. Infect Immun 2002; 70:4812–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu H, Karunakaran KP, Jiang X, Shen C, Andersen P, Brunham RC. Chlamydia muridarum T cell antigens and adjuvants that induce protective immunity in mice. Infect Immun 2012; 80:1510–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abraham S, Juel HB, Bang P, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the chlamydia vaccine candidate CTH522 adjuvanted with CAF01 liposomes or aluminium hydroxide: a first-in-human, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:1091–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]