Abstract

Purpose

To review the current literature to determine which injection technique and needle portal placement provide the greatest accuracy for intra-articular access to the knee.

Methods

This study followed Preferred Reporting Items and Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in March 2020 and repeated in May 2020 using electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Library. Data on the accuracy of intra-articular knee injection (successful injections/total number of injections) were collected. Only Level I studies were included. Study design, demographic variables, needle sizes, and method of validating accuracy were recorded. The Jadad score was used to assess methodologic quality, and a risk-of-bias assessment was performed.

Results

A total of 12 Level I human studies (1431 patients, 1315 knees) were included in this review. Seven of the studies did a direct comparison between ultrasound-guided and blind knee injections. Ultrasound-guided injections were more accurate compared with blinded knee injections in every study. The most accurate anatomical approach was an isometric quadricep contraction method with the superolateral approach.

Conclusions

This study showed that ultrasound-guided knee injections were more accurate across every anatomical needle injection site compared with blind injections. Injections made by a blind/anatomically guided method had inconsistent accuracy rates that seemed highly dependent on the portal of entry.

Level of Evidence

Level I, systematic review of Level I studies.

Intra-articular knee injections (IAKIs) are a common alternative to systemic pharmaceutical treatments. Injections of various compounds are designed to reduce inflammation, possibly slow the increasing degeneration of the joint, and decrease pain. Commonly injected agents include corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, blood-derived products such as platelet-rich plasma, and biologic cellular products from the bone marrow, placenta, and/or adipose tissue.1 It is essential for these compounds to directly enter the intra-articular joint to achieve maximum efficacy.2 Complications can arise from misplaced injections that include pain or swelling at the site of injection, inflammation of the synovium,2 and septic arthritis.3

There are many different techniques for injecting the knee, with the most common being an anatomical-based approach. This method uses various visualized and palpated anatomical landmarks. For example, with the superolateral injection technique, the patient is positioned supine with legs extended. The physician then palpates the patella and inserts the needle on the supralateral surface of the patella, aimed toward the center of the patella and directed slightly posteriorly and inferomedially into the knee joint.4 To identify the correct trajectory and depth for needle placement, physicians also can elect to use other methods to confirm needle placement, including fluoroscopy,5 air arthrogram,6 backflow technique,7 and ultrasound devices.8 There is also no clear consensus on the “best” technique or the most accurate approach portal (needle insertion site) for knee aspiration and injection. The purpose of this study was to review the current literature to determine which injection technique and needle portal placement provides the greatest accuracy for intra-articular access to the knee. We hypothesized that our literature review would demonstrate that one knee injection technique and needle portal placement would be more accurate than others.

Methods

Search Strategies for Study Selection

This study followed the 2009 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines and the PRISMA-IPD statement.9 A comprehensive search of the literature was carried out in February 2020 using electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Library. The databases were searched individually for all possible terms and combination of terms to accommodate differences in their search engines. The key words used in the searches were “intra-articular knee” AND “injection” OR “aspiration” AND “accuracy” filtered by “human” and “randomized controlled trial.” Two authors (W.H.F. and X.T.C.) screened studies for eligibility and any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (C.T.V.).

Study Selection Criteria

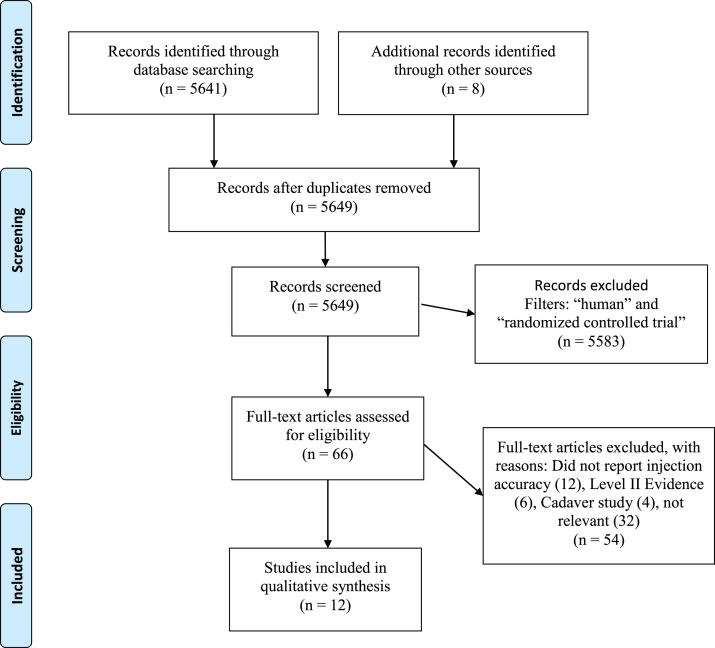

Only Level I evidence studies, defined by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine,10 published in English, that reported the accuracy for IAKI with any technique and portal were considered for inclusion (Fig 1). W.H.F.-extracted data, including patient population, sample size, intervention, evaluation of accuracy, injection technique, needle size, and results, were recorded but not used as basis of inclusion/exclusion. Basic science in vitro, animal studies, letters to the editor, editorials, personal correspondence, study protocols, Levels II to V evidence, and studies investigating patient reported outcomes after IAKI were excluded.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram on the process of literature search, screening, full-text review, and study inclusion based on PRISMA guidelines. (PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.)

Quality Assessment

Study quality assessment was carried out using the Jadad scale.11 This scoring system awards points to trials for incorporating the following key aspects of trial design: randomization, blinding, and accounting for withdrawals. A score of 3 or more classified the study as high-quality.10 Two reviewers (W.H.F. and X.T.C.) independently carried out the assessments and scored the publication for quality. Any discrepancies in the results were resolved through discussion.

Risk of Bias Assessment

A risk of bias assessment was independently performed by 2 reviewers (W.H.F. and X.T.C.) using the modified Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Assessment Tool.12 Each reviewer assigned a value of “high,” “low,” or “unclear” bias for each study using the following parameters: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between reviewers. A study was deemed to be at an overall low-risk of bias if it met criteria for low-risk within the domains of participant blinding, selection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias.13

Statistical Analysis

Only descriptive statistics were performed for the study cohort characteristics and Jadad scores.

Results

Overview

The initial search yielded 5641 results after duplicates were removed. Eight studies were identified from bibliographies. These results were filtered to only include “human” species and to include “randomized controlled trials,” leaving 66 results for full text review. Of the 66 full-text articles reviewed, 54 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Twelve studies did not report injection accuracy, 32 studies were determined to be irrelevant based on title and abstract, 4 studies were cadaver studies, and 6 studies were Level II evidence. A total of 12 Level I knee injection studies were available for qualitative synthesis (Fig 1). A total of 12 Level I human studies (1431 patients, 1,315 knees) were included in this review (Table 1). The majority of Level I studies gathered in this review (8/12)14-21 compared the accuracy of ultrasound-guided versus blind or landmark injection/arthrocentesis. Only 4 of 12 studies22, 23, 24, 25 compared the accuracy of anatomical-guided approaches. The majority of studies recruited patients with radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis (9/12 studies). One study looked at patients requiring knee arthrocentesis,18 1 study studied patients presenting for routine knee arthroscopy,25 and 1 study recruited patients with a diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis.21

Table 1.

Overview of Studies

| Overview |

Demographics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Number of Knees | Patients per Study Arm | Population | Country | Mean Age | Male | Female |

| Park et al., 201314 | n = 120 | n = 40 for each arm | Patients with degenerative OA (K-L 2 or 3) | Korea | 63.59 | 21 | 99 |

| Im et al., 200915 | n = 89 | n = 45 for sonographically guided, n = 44 for blind injection | Patients with radiographically confirmed knee OA (K-L 2 or 3) | Korea | 60.10 | 24 | 65 |

| Jang et al., 201316 | n = 126 | n = 44 for ultrasound, n = 41 for out of plane, n = 41 for blind injection | Patients with radiographically confirmed knee OA (K-L 2 or 3) | Korea | 61.55 | 27 | 99 |

| Park et al., 201217 | n = 99 | n = 50 for ultrasound, n = 49 for blind injection | Patients with radiographically confirmed knee OA | Korea | 60.00 | 28 | 72 |

| Wiler et al., 201018 | n = 66 | n = 39 for ultrasound, n = 27 for landmark | Patients requiring knee arthrocentesis | USA | 79.75 | 43 | 23 |

| Sibbitt et al., 201219 | n = 64 | n = 22 for anatomic-guided, n = 22 for ultrasound-guided with mechanical aspirating syringe, n = 20 for ultrasound-guided with automatic aspirating syringe | Patients with arthritis (K-L 1-3) and persistent pain in involved joint | USA | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hashemi et al., 201620 | n = 220 | n = 100 for ultrasound, n = 123 for blind injection | Patients with osteoarthritis diagnosis based on American College of Rheumatology definition | Iran | 64.07 | 60 | 163 |

| Cunnington et al., 201021 | n = 68 | n = 35 for ultrasound, n = 33 for clinical examination–guided | Patients with a diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis | USA | 58.15 | N/A | N/A |

| Toda et al., 200822 | n = 50 | n = 50 for modified Waddell, n = 50 for anteromedial approach, and n = 50 for lateral patellar approach | Patients with medial compartment OA knee | USA | 66.10 | 8 | 42 |

| Wada et al., 201823 | n = 150 | n = 75 for isometric quadriceps method, n = 75 for nonactivated quadriceps method | Patients with radiographically confirmed knee OA | Japan | 73.55 | 75 | 75 |

| Chernchujit et al., 201924 | n = 132 | n = 66 for modified anterolateral, n = 66 for superolateral | Patients with symptomatic OA without effusion | Thailand | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wind et al., 200425 | n = 131 | n = 44 for superolateral, n = 43 for superomedial, n = 44 for lateral joint | Patients presenting for routine knee arthroscopy | USA | 43.00 | N/A | N/A |

K-L, Kellgren-Lawrence; OA, osteoarthritis; N/A, not available.

Lastly, the evaluation for injection accuracy also varied between the studies in this comparison. Six studies (50%) took postinjection radiographs and had a blinded radiologist judge whether the injected compound was successfully placed in the intra-articular space.14, 15, 16, 17,21,22 Two of 12 studies (16.7%) studied successful arthrocentesis accuracy based on fluid aspiration and aspirated fluid volume instead of injection accuracy (Table 2).18,19 The other studies used a variety of methods to verify accuracy, including injecting contrast and using fluoroscopy,20 using an ultrasound probe to verify that the solution diffused within the joint,23 using mini air-arthrography,24 and injecting methylene blue dye and grading during arthroscopy.25

Table 2.

Overview of Treatment

| Study | Sample Size | Number of Knees | Needle Size | Intervention | Evaluation of Accuracy | Main Evaluation Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park et al. 201314 | n = 120 | n = 120 | 23-gauge, 1.5-in, or 3.5-in needles | Nonionic contrast medium | Lateral and anteroposterior radiographs | Blinded radiologist judging |

| Im et al. 200915 | n = 89 | n = 89 | 21-gauge needle, 1.5-in | 3 intra-articular injections of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid | Postinjection radiographic evaluation | Blinded radiologist judging |

| Jang et al. 201316 | n = 126 | n = 126 | 23-gauge, 1.5-in needle or 2-in, 23-gauge needle | Triamcinolone and nonionic contrast agent | Postinjection radiographic evaluation | Blinded radiologist judging |

| Park et al. 201217 | n = 99 | n = 99 | 21-gauge needle, 1.5- inch | 3 intra-articular injections of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid | Lateral and anterior posterior radiograph and postinjection radiographic evaluation | Blinded radiologist judging |

| Wiler et al. 201118 | n = 66 | n = 66 | 18-gauge needle | Arthrocentesis | Successful aspiration (>5 mL synovial fluid), provider sense of ease of procedure, and amount of fluid obtained | Successful aspiration |

| Sibbitt et al. 201119 | n = 64 | n = 64 | 25-gauge 1.5-inch needle and 18-gauge, 1.5-inch needle | Arthrocentesis | Aspirated fluid volume, successful aspirations, Pain by VAS | Successful aspiration |

| Hashemi et al. 201620 | n = 220 | n = 220 | N/A | Hyaluronic acid | Postinjection fluoroscopy evaluation | Fluoroscopy after injection |

| Cunnington et al. 201021 | n = 184 | n = 68 | 21-gauge needle | 40 mg of triamcinolone acetonide, lidocaine, and contrast agent | Postinjection radiographic evaluation | Blinded radiologist judging |

| Toda et al. 200822 | n = 50 | n = 50 | 23-gauge needle, 1.25-in | 3 intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid at 0, 2, 4 weeks | Postinjection radiographic evaluation | Blinded radiologist judging and clinical Lequesne index at final and at baseline |

| Wada et al. 201823 | n = 150 | n = 150 | N/A | Hyaluronic Acid | Ultrasound probe used to see if solution diffused within the joint | Radiographic measurements |

| Chernchujit et al. 201924 | n = 132 | n = 132 | 25-gauge needle | Air and medical agents | Mini air-arthrography and post injection radiographic evaluation | Accuracy rate, Pain VAS |

| Wind et al. 200425 | n = 131 | n = 131 | 18-gauge, 1.5 in needle | Methylene blue with normal saline | Examined intra-articularly for evidence of methylene blue staining during arthroscopy | Single investigator looking at staining |

N/A, not available; VAS, visual analog scale.

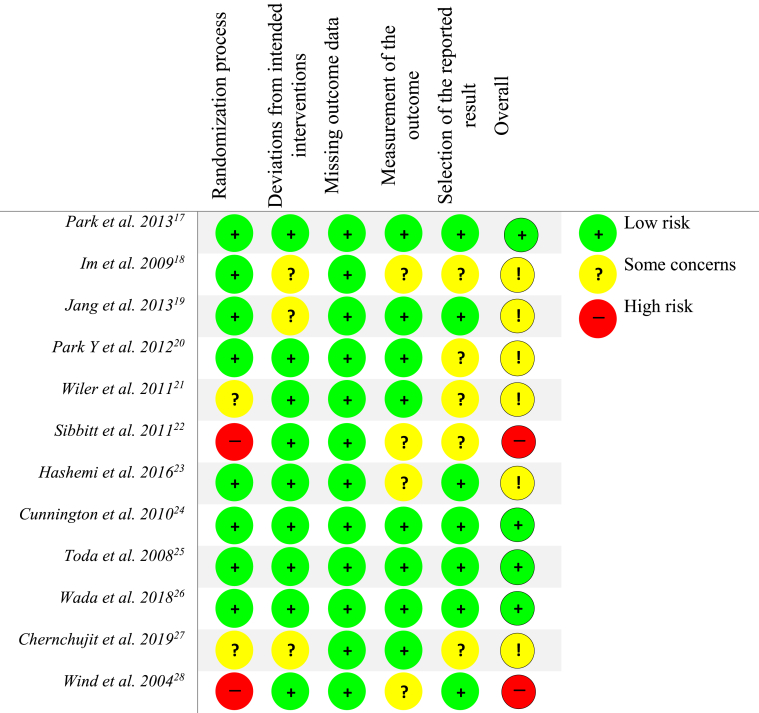

Risk of Bias Assessment

Four of the 12 studies (33.3%) were considered “low risk” of bias, whereas the remaining 8 studies were graded at “some concerns” or had “high risk” of bias based on the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Fig 2).14,21, 22, 23 The randomization process was poorly reported or not reported in 2 studies (16.7%).20,25 The remaining 10 studies (83.3%) had appropriate randomization protocols including envelopes, simple randomization, and block randomization. Inconsistent blinding was a source of bias that affected the majority of studies. Six studies (50%) had a blinded radiologist judging whether the injections were accurate, whereas the other 6 studies did not carry out a blinded assessment. The participants in 5 studies (41.6%) were blinded to the treatment group to which they were assigned, whereas participants were aware of which treatment group they were in 6 studies (50%). One study did not specify blinding (8%).20

Fig 2.

Risk of bias assessment.

Methodologic Quality: Jadad Score

Five studies (41.6%) had a Jadad score of 3 or greater11 and were deemed high-quality trials (Table 3). Many of the studies lost points for failing to double blind. Only Cunnington et al.21 and Toda et al.22 conducted double-blinded, randomized controlled trials with appropriate blinding. The remaining 10 studies were single-blinded trials in which either patients or clinicians were not blinded to the intervention groups. Four studies (33%) did not adequately describe the randomization process19,20,24,25 and 4 studies (33%) did not describe patient dropouts or withdrawals.16, 17, 18,20

Table 3.

Jadad Score

|

Study |

1. Was the Study Described as Random? | 2. Was the Randomization Scheme Described and Appropriate? | 3. Was the Study Described as Double-Blind? | 4. Was the Method of Double Blinding Appropriate? | 5. Was There a Description of Dropouts and Withdrawals? | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park et al., 201314 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 3 |

| Im et al., 200915 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 3 |

| Jang et al., 201316 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 |

| Park et al., 201217 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 1 | 2 |

| Wiler et al., 201118 | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 |

| Sibbitt et al., 201119 | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 2 |

| Hashemi et al., 201620 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Cunnington et al., 201021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Toda et al., 200822 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Wada et al., 201823 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 3 |

| Chernchujit et al., 201924 | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 2 |

| Wind et al., 200425 | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | 2 |

IAKI Accuracy

Eight studies did a direct comparison of ultrasound-guided versus blind injection/arthrocentesis, as shown in Table 4. Ultrasound-guided injections were more accurate in every study regardless of the portal of injection. One study, Park et al.,14 compared the accuracy of ultrasound-guided injections in the midmedial portal, the superolateral portal, and the midlateral portal and reported injection accuracies of 95% (38/40), 100% (40/40), and 98.5% (39/40), respectively. The biggest difference in injection accuracy was found in Jang et al.16 and Im et al.’s studies.15 Jang et al.16 compared accuracy rates through the midmedial portal and found that ultrasound was 97% accurate (43/44) whereas blind injections were only 78% accurate (32/41). Im et al.15 compared accuracy rates through the midpatellar portal and found that ultrasound-guided injections were 95.6% accurate (43/45) whereas blind injections were only 77.3% accurate (43/44).

Table 4.

Ultrasound Versus Blind Injection Comparison

| Midmedial Portal | Midpatellar Portal | Suprapatellar Bursa | Supralateral | Superolateral | Midlateral | Unspecified | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park et al., 201314 | 95% (38/40) | 100% (40/40) | 98.5% (39/40) | ||||||||||

| Im et al., 200915 | 95.6% (43/45) | 77.3% (34/44) | |||||||||||

| Jang et al., 201316 | 97% (43/44) | 78% (32/41) | |||||||||||

| Park et al., 201217 | 96% (48/50) | 83.7% (41/49) | |||||||||||

| Wiler et al., 201118 | 95% (37/39) | 93% (25/27) | |||||||||||

| Sibbitt et al., 201119 | 100% (42/42) | 82% (18/22) | |||||||||||

| Hashemi et al., 201620 | Expert: 98% (49/50) Inexpert: 94% (47/50) | Expert: 95.74% (45/47) Inexpert: 79% (60/76) |

|||||||||||

| Cunnington et al., 201021 | 91% (32/35) | 82% (27/33) | |||||||||||

NOTE. Ultrasound-guided is bolded on the left, blind injection is on the right.

Four studies compared the IAKI accuracy rate from different anatomical approaches (Table 5). The most accurate approach was reported in Wada et al.23 at 93.3% (70/75), who used an isometric quadriceps contraction method through the superolateral approach into the suprapatellar joint space. Wind et al.25 reported that their injection accuracy through the superomedial approach was also high at 93% (40/43). The modified anteromedial approach was used by 2 studies, Toda et al.22 and Chernchujit et al.,24 and had an accuracy rate of 86% (43/50) and 89% (59/66), respectively. In a single study looking at the superolateral approach, Chernchujit et al. reported the accuracy only being 58% (38/66).

Table 5.

Anatomical Accuracy Comparison

| Modified Anteromedial Approach | Anteromedial | Lateral Patellar Approach | Superolateral | Superomedial | Lateral Joint Line | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toda et al., 200822 | 86% (43/50) | 62% (31/50) | 70% (35/50) | |||

| Wada et al., 201823 | Activated quads: 93.3% (70/75) Nonactivated quads: 80% (60/75) |

|||||

| Chernchujit et al., 201924 | 89% (59/66) | 58% (38/66) | ||||

| Wind et al., 200425 | 89% (39/44) | 93% (40/43) | 75% (98/131) |

NOTE. Successful injection % (number of intra-articular injections / total number of knees).

Discussion

The results showed that ultrasound-guided knee injections were more accurate across every anatomical needle injection site compared with blind injections. Injections made by blind/anatomically guided techniques had inconsistent accuracy rates that seemed highly dependent on the portal of entry.

There is a need to standardize knee injection procedures to improve safety and efficacy by employing the most accurate injection techniques possible. It has been reported that traditional knee injections have a relatively low accuracy rate, with 1 of every 4 injections being delivered extra-articularly.2 Knee injections and knee arthrocentesis are 2 commonly performed clinical practices that require entering the joint capsule for maximum efficacy. It is crucial to deliver the often-expensive compounds directly into the intra-articular joint to minimize any side effects. Possible adverse effects of injecting extra-articularly into the joint include increased pain, skin rash, flushing, difficulty moving the knee, and infections.26,27

Numerous imaging modalities can help the physician visualize the joint capsule and improve injection accuracy. However, there is relatively low evidence for the success of many of these techniques, including the use of fluoroscopy,2,28,29 computed tomography,30, 31, 32 and magnetic resonance imaging. There is little to no existing Level I literature on these imaging modalities used to visualize the joint for injections or arthrocentesis, making their effectiveness difficult to generalize to a general study population. These techniques also have potential drawbacks of radiation exposure to the patient, use of contrast, equipment expense, lack of portability, and specialized room requirements. Ultrasonography is one of the most practical options because it is a noninvasive imaging method that can provide real-time visualization of the needle directed into the target structure being injected.33 Ultrasound devices are also accessible, relatively inexpensive, and highly accurate in experienced hands.34 Studies also have found that ultrasound injection guidance was more cost-effective to patients, with a 58% ($224) reduction in cost per responder per year.35 In addition, there is no risk of radiation and no need for injected contrast material.

Other non-Level I studies have compared the accuracy rate of IAKI and have generally found significantly greater accuracy rates and improved patient-reported outcomes compared with blind injections. Maricar et al.36 found that the accuracy rate of image-guided injections was more accurate compared with blinded injections and reported that guided injections through the lateral sites had excellent accuracy (95%-100%). When comparing blinded injections, they reported that injections through the superolateral patellar as being the most accurate, and that about 1 in 5 blinded IAKI were inaccurate. These results were limited by the inclusion of nonrandomized controlled trials and cadaver studies where altered tissue properties may affect the accuracy of the knee injections. Wu et al.37 compared ultrasound-guided versus landmark injections in knee arthrocentesis and found statistically significant differences in favor of ultrasound guided for accuracy and lowered procedural pain scores. In their methodology for inclusion of studies, they included nonrandomized controlled trials and cadaver studies that could be subject to bias and have a greater risk of systematic errors. Hermans et al.38 compiled anatomical accuracy studies and reported that the superolateral approach resulted in high accuracy rates with the highest pooled accuracy of 91%. Berkoff et al.39 focused on the clinical utility of ultrasound guidance and found that using ultrasound-guided injections directly improved patient reported clinical outcomes and was most cost-effective. They however, had a small sample size and compared injections in both the knee and shoulder.

In our level I analysis, ultrasound-guided injections had excellent accuracy (>95%) through every anatomical approach in the knee. Comparatively, the blinded injection had a variable accuracy that ranged between the lowest of 77.3% (34/44)15 with the midpatellar approach and the highest of 95.74% (45/47)20 with the supralateral approach. In Hashemi et al.’s study, they also compared the differences in injectors’ experience on the accuracy of IAKI. Their study reported much greater missed injection rates in the inexpert blind injections 79% (60/76), with no significant differences in the inexpert ultrasound-guided injections 94% (47/50) and the expert ultrasound group 94% (47/50). Other non-Level I studies have also reported that injector’s experience influenced the accuracy rate. Curtiss et al.40 found in a cadaver study that inexperienced injections with the superolateral patellar approach only had an accuracy rate of 55%, whereas more experienced injectors had an accuracy rate of 100%. Cunnington et al.21 used an inexperienced rheumatology trainee for all ultrasound-guided injections and still had relatively high accuracy rates, 91% (32/35), compared with clinical examination–guided IAKI performed by rheumatology consultants (median 15 years’ experience), 82% (27/33). Interestingly in the anatomical accuracy comparison chart in Table 5, Chernchujit et al.24 reported that the accuracy for blind IAKI to superolateral approach only was 58% (38/66).

Injections and aspirations are commonly used throughout musculoskeletal medicine. However, needle usage often causes patients to feel unsatisfied with treatment from the resulting pain and anxiety. To combat this issue, smaller needle diameters, new safety technology, and needle-free injection techniques have been proposed.41 The appropriate needle gauge and length are determined by several factors, including the target tissue and injection formulation.42,43 For intra-articular knee aspirations, conventional syringes can cause “traumatic tap,” or frank blood, in the aspiration and may lead to tissue damage. Moorjani et al.44 found that by changing from a conventional syringe to a mechanical reciprocating procedure device (RPD), improved needle control and lead to decreased patient pain, and improved fluid aspirate yields. Additionally, aspirations need to balance between the vacuum force generated and the type of syringe used. Haseler et al.45 found that if a needle or syringe size was too small, not enough force could be generated, which would lower the biopsy sample yield. The authors recommended to use larger syringes (10 or 20 mL) with 2 hands, or mechanical syringes (RPD) with one hand to make aspiration easier and improve needle control. The use of RPD technology has also led to statistically significant lower levels of patient-reported outcomes on the visual analog scale, as well as physician satisfaction.46

The studies in this analysis used varying sized needles and syringes for the injection/aspiration procedure. The two studies that studied arthrocentesis both used large 18-gauge needles to maximize fluid collected.18,19 The remaining injections studies used much thinner needles, with 3 studies using 25-gauge needles, 3 studies using 21-gauge needles, 2 studies did not report needle size, and one study with a 25-gauge needle. Larger needle sizes could potentially lead to a greater chance of missed injection, with reports stating that larger needle size had a greater chance of causing pain.42 The length of the needle is also important for reaching inside the joint capsule. Jackson et al.2, in a Level II fluoroscopy study, stated that a shorter 1.5 in needle through the anterolateral portal caused (9/13) injections to end up in the extra-articular space.2 They went back and evaluated the size of the fat pad using magnetic resonance imaging scans and determined that an appropriate needle size to be 2 inches. The additional 0.5 inches of the needle would help clear the intra-articular fat pad and reach the intra-articular space. Almost all the included studies used a needle size shorter than 2 inches when injecting to determine accuracy.14,16 Lastly, many studies did not report the type of syringe used in either aspiration or injection, adding an additional point of variability.

This current study did not look at patient-reported outcomes, but future studies should analyze whether difference in guided injections or knee portals affect patient-reported outcomes. In randomized controlled trials, Kianmehr et al.47 compared the difference in effect of sonographic-guided and blind injections and found statistically significant changes in both short-term and long-term follow-up for Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index pain and functional scores for guided injections. This was also confirmed in other trials that compared patient-reported outcomes. Sibbitt et al.35 found that sonographic guidance not only led to reduction in injection pain but also increased responder rate and therapeutic duration. When comparing only anatomical guided injections, Dávila-Parrilla et al.48 found that accuracy rates did not affect patient-reported visual analog scale and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index scores as much as injecting through the superolateral portal compared with the anterolateral portal. In contrast, when Wagner et al.49 compared the efficacy of anatomical guidance through the superolateral, anteromedial, and anterolateral approach, they found no significant differences in patient-reported outcomes.

Limitations

This study has limitations. In 2 of the studies, randomization methods were not described clearly in the manuscript, leading to potential bias. In addition, it is difficult to conclude where and how to inject into the knee because of the heterogeneity of the included studies. The materials injected, patient population, and needle size all varied considerably among the included studies, which can influence the outcome of the assessment. The procedural methods used in these knee injection studies also varied: 5 studies injected hyaluronic acid,14,15,20,22 23 3 studies injected corticosteroid followed by a contrast agent,14,17,21 and 2 studies performed arthrocentesis.18,19 One study injected air and medical agents,24 and 1 study injected methylene blue dye directly into the joint.25 The differences in injected agents could lead to variability in detection, potentially confounding accuracy. As mentioned before, the evaluation of injection accuracy was not consistent. Most of the studies used a blinded radiologist to judge, which would be the least biased method. However, several studies only had a single unblinded investigator that judged accuracy through ultrasound,23 fluoroscopy,20 mini air arthrography,24 or staining.24 Studies have shown that having an unblinded outcome assessor can lead to biased estimates of treatment effect and can skew results.50,51

Conclusions

This study showed that ultrasound-guided knee injections were more accurate across every anatomical needle injection site compared with blind injections. Injections made by a blind/anatomically guided method had inconsistent accuracy rates that seemed highly dependent on the portal of entry.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: T.V. reports nonfinancial support from KeraLink, CarthroniX, Align-Med, Parcus Med, and Replenish, during the conduct of the study. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Liu S.H., Dube C.E., Eaton C.B., Driban J.B., McAlindon T.E., Lapane K.L. Longterm effectiveness of intraarticular injections on patient-reported symptoms in knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:1316–1324. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.171385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson D.W., Evans N.A., Thomas B.M. Accuracy of needle placement into the intra-articular space of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1522–1527. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charalambous C., Tryfonidis M., Sadiq S., Hirst P., Paul A. Septic arthritis following intra-articular steroid injection of the knee—a survey of current practice regarding antiseptic technique used during intra-articular steroid injection of the knee. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22:386–390. doi: 10.1007/s10067-003-0757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esenyel C., Demirhan M., Esenyel M. Comparison of four different intra-articular injection sites in the knee: A cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:573–577. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beukelman T., Arabshahi B., Cahill A.M., Kaye R.D., Cron R.Q. Benefit of intraarticular corticosteroid injection under fluoroscopic guidance for subtalar arthritis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2330–2336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glattes R.C., Spindler K.P., Blanchard G.M., Rohmiller M.T., McCarty E.C., Block J. A simple, accurate method to confirm placement of intra-articular knee injection. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1029–1031. doi: 10.1177/0363546503258703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luc M., Pham T., Chagnaud C., Lafforgue P., Legre V. Placement of intra-articular injection verified by the backflow technique. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:714–716. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qvistgaard E., Kristoffersen H., Terslev L., Danneskiold-Samsøe B., Torp-Pedersen S., Bliddal H. Guidance by ultrasound of intra-articular injections in the knee and hip joints. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9:512–517. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips B., Ball C., Sackett D. Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine-levels of evidence (March 2009). 2009. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine: Levels of Evidence (March 2009)—Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM), University of Oxford. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/oxford-centre-for-evidence-based-medicine-levels-of-evidence-march-2009

- 11.Clark H.D., Wells G.A., Huët C. Assessing the quality of randomized trials: Reliability of the Jadad scale. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20:448–452. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundh A., Gøtzsche P.C. Recommendations by Cochrane Review Groups for assessment of the risk of bias in studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park K.D., Ahn J.K., Lee S.-C., Lee J., Kim J., Park Y. Comparison of ultrasound-guided intra-articular injections by long axis in plane approach on three different sites of the knee. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92:990–998. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3182923691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Im S.H., Lee S.C., Park Y.B., Cho S.-R., Kim J.C. Feasibility of sonography for intra-articular injections in the knee through a medial patellar portal. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1465–1470. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.11.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang S.H., Lee S.C., Lee J.H., Nam S.H., Cho K.R., Park Y. Comparison of ultrasound (US)-guided intra-articular injections by in-plain and out-of-plain on medial portal of the knee. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:1951–1959. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park Y.B., Ah Choi W., Kim Y.K., Chul Lee S., Hae Lee J. Accuracy of blind versus ultrasound-guided suprapatellar bursal injection. J Clin Ultrasound. 2012;40:20–25. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiler J.L., Costantino T.G., Filippone L., Satz W. Comparison of ultrasound-guided and standard landmark techniques for knee arthrocentesis. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sibbitt W., Jr., Kettwich L., Band P. Does ultrasound guidance improve the outcomes of arthrocentesis and corticosteroid injection of the knee? Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41:66–72. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2011.599071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashemi S.M., Hosseini B., Zhand M., Pourrosta R. Accuracy of ultrasound guided versus blind knee intra articular injection for knee osteoarthritis prolotherapy. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access. 2016;5 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunnington J., Marshall N., Hide G. A randomized, double-blind, controlled study of ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injection into the joint of patients with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1862–1869. doi: 10.1002/art.27448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toda Y., Tsukimura N. A comparison of intra-articular hyaluronan injection accuracy rates between three approaches based on radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:980–985. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wada M., Fujii T., Inagaki Y., Nagano T., Tanaka Y. Isometric contraction of the quadriceps improves the accuracy of intra-articular injections into the knee joint via the superolateral approach. JBJS Open Access. 2018;3 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.18.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chernchujit B., Tharakulphan S., Apivatgaroon A., Prasetia R. Accuracy comparisons of intra-articular knee injection between the new modified anterolateral Approach and superolateral approach in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis without effusion. Asia Pac J Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Technol. 2019;17:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.asmart.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wind W.M., Jr., Smolinski R.J. Reliability of common knee injection sites with low-volume injections. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:858–861. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinks A., Koes B.W., Volkers A.C., Verhaar J.A., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M. Adverse effects of extra-articular corticosteroid injections: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peeters C., Leijs M.J., Reijman M., van Osch G., Bos P. Safety of intra-articular cell-therapy with culture-expanded stem cells in humans: A systematic literature review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1465–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waddell D., Estey D., Bricker D., Marsala A. Viscosupplementation under fluoroscopic control. Am J Med Sports. 2001;3 327-241, 249. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myung J.S., Lee J.W., Lee J.Y. Usefulness of fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular injection of the knee. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2007;56:563–567. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vande Berg B.C., Lecouvet F.E., Poilvache P. Dual-detector spiral CT arthrography of the knee: Accuracy for detection of meniscal abnormalities and unstable meniscal tears. Radiology. 2000;216:851–857. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au08851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pathria M., Sartoris D., Resnick D. Osteoarthritis of the facet joints: Accuracy of oblique radiographic assessment. Radiology. 1987;164:227–230. doi: 10.1148/radiology.164.1.3588910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Filippo M., Bertellini A., Pogliacomi F. Multidetector computed tomography arthrography of the knee: Diagnostic accuracy and indications. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daniels E.W., Cole D., Jacobs B., Phillips S.F. Existing evidence on ultrasound-guided injections in sports medicine. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6 doi: 10.1177/2325967118756576. 2325967118756576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson J.A. Ultrasound in sports medicine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:363–386. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(02)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sibbitt W.L., Jr., Band P.A., Kettwich L.G., Chavez-Chiang N.R., DeLea S.L., Bankhurst A.D. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the cost-effectiveness of sonographic guidance for intra-articular injection of the osteoarthritic knee. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:409–415. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31823a49a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maricar N., Parkes M.J., Callaghan M.J., Felson D.T., O'Neill T.W. Where and how to inject the knee—a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu T., Dong Y., xin Song H., Fu Y., hua Li J. Ultrasound-guided versus landmark in knee arthrocentesis: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:627–632. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermans J., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M., Bos P.K., Verhaar J.A., Reijman M. The most accurate approach for intra-articular needle placement in the knee joint: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkoff D.J., Miller L.E., Block J.E. Clinical utility of ultrasound guidance for intra-articular knee injections: A review. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:89. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S29265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtiss H.M., Finnoff J.T., Peck E., Hollman J., Muir J., Smith J. Accuracy of ultrasound-guided and palpation-guided knee injections by an experienced and less-experienced injector using a superolateral approach: A cadaveric study. PM R. 2011;3:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dumas H., Panayiotopoulos P., Parker D., Pongpairochana V. Understanding and meeting the needs of those using growth hormone injection devices. BMC Endocr Disord. 2006;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill H.S., Prausnitz M.R. Does needle size matter? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1:725–729. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Škalko-Basnet N. Biologics: The role of delivery systems in improved therapy. Biologics. 2014;8:107. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S38387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moorjani G.R., Michael A.A., Peisajovich A., Park K.S., SIBBITT W.L., Bankhurst A.D. Patient pain and tissue trauma during syringe procedures: A randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1124–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haseler L.J., Sibbitt R.R., Sibbitt W.L., Michael A.A., Gasparovic C.M., Bankhurst A.D. Syringe and needle size, syringe type, vacuum generation, and needle control in aspiration procedures. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2011;34:590–600. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-0011-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nunez S.E., Draeger H.T., Rivero D.P., Kettwich L.G., Sibbitt W.L., Jr., Bankhurst A.D. Reduced pain of intraarticular hyaluronate injection with the reciprocating procedure device. J Clin Rheumatol. 2007;13:16–19. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000256280.85507.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kianmehr N., Hasanzadeh A., Naderi F., Khajoei S., Haghighi A. A randomized blinded comparative study of clinical response to surface anatomy guided injection versus sonography guided injection of hyaloronic acid in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis. Int J Rheumatic Dis. 2018;21:134–139. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dávila-Parrilla A., Santaella-Santé B., Otero-López A. Does injection site matter? A randomized controlled trial to evaluate different entry site efficacy of knee intra-articular injections. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2015;107:78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagner B.S., Howe A.S., Dexter W.W. Tolerability and efficacy of 3 approaches to intra-articular corticosteroid injections of the knee for osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3 doi: 10.1177/2325967115600687. 2325967115600687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kahan B.C., Rehal S., Cro S. Blinded outcome assessment was infrequently used and poorly reported in open trials. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hróbjartsson A., Thomsen A.S.S., Emanuelsson F. Observer bias in randomized clinical trials with measurement scale outcomes: A systematic review of trials with both blinded and nonblinded assessors. CMAJ. 2013;185:E201–E211. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.