Mitochondrial activity is becoming an inherent aspect of cellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis). In this issue, Schlagowski et al (2021) report on the attractive notion that modulating mitochondrial protein import activity stimulates protein aggregate clearance in the cytosol, thereby affecting cytosolic proteostasis and its collapse observed in neurodegenerative diseases.

Subject Categories: Membrane & Intracellular Transport, Neuroscience, Protein Biosynthesis & Quality Control

A new study finds upregulation of the mitochondrial protein import machinery to stimulate clearance of cytosolic protein aggregates.

Mitochondria are multitasking organelles responsible for energy conversion. However, the big responsibility of being such a “powerful” organelle comes with a cost. The endosymbiotic origin of mitochondria resulted in the enclosure of the organelle by lipid membranes and retaining only a small genome. Consequently, a majority of mitochondrial proteins are nuclear‐encoded and synthesized by cytosolic ribosomes. Therefore, they have to be actively transported to mitochondria through a sophisticated system of protein translocases and sorting machineries that undergo constant surveillance (Pfanner et al, 2019). If for any reason mitochondrial protein import is impaired, mitochondrial precursor proteins stay in the cytosol where they challenge cellular proteostasis. This activates beneficial stress response mechanisms aiming at inhibition of protein production, chaperone stimulation, and increase of proteasomal protein degradation (Wang & Chen, 2015; Wrobel et al, 2015; Boos et al, 2019; Sladowska et al, 2021) (Fig 1). Moreover, several surveillance mechanisms also act on the level of mitochondrial precursor proteins entering mitochondria through the TOM complex (Izawa et al, 2017; Weidberg & Amon, 2018; Martensson et al, 2019).

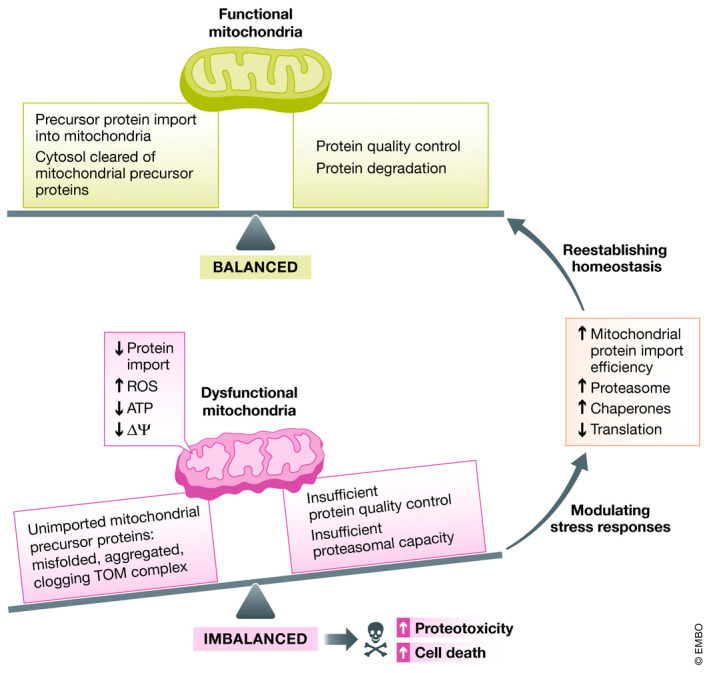

Figure 1. Balancing out mitochondrial protein import efficiency with cellular proteostasis.

Under healthy conditions, mitochondrial precursor proteins are efficiently imported into mitochondria and the presence of unimported precursor proteins in the cytosol is controlled by chaperones and protein degradation systems. However, under stress conditions, such as mitochondrial protein import slowdown, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, loss of ATP, and low mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ), mitochondrial protein import is perturbed resulting in clogging of the TOM complex and accumulation and aggregation of misfolded mitochondrial precursor proteins in the cytosol. This in turn challenges protein quality control and degradation systems posing a threat to cellular protein homeostasis. To counteract it, stress responses can be activated to reestablish cellular proteostasis by increasing mitochondrial protein import efficiency, proteasome activity, and chaperone levels and by decreasing protein synthesis.

Interestingly, cytosolic protein aggregation has been linked to mitochondrial activity. On the one hand, induction of pathways caused by mitochondrial stress originating from inside of mitochondria stimulates amyloid‐β and polyQ aggregate clearance (Labbadia et al, 2017; Sorrentino et al, 2017). On the other, deficiency in protein import and accumulation of mitochondrial precursor proteins in the cytosol, in which their levels cannot be sufficiently controlled by the proteasome, leads to their cytosolic aggregation (Nowicka et al, 2021).

In this study, Schlagowski et al (2021) propose an approach to overcome proteotoxic stress in the cytosol by taking advantage of boosting the effectiveness of the mitochondrial import pathway. As a marker of proteotoxic stress in yeast cells, the authors employed a model polyQ protein that is linked to neurodegenerative processes in humans. At first, the authors found that polyQ aggregation combined with mitochondrial import deficiency escalated proteotoxicity and led to growth arrest caused by cell death. Next, they tested the consequences of increased Mia40 levels. They observed that an excess of Mia40, as well as of other components of the mitochondrial import machinery (Erv1, Tim9, Sam50, Sam37), protected cells against polyQ aggregation‐mediated growth arrest. The authors discovered that Mia40 beneficial effect is due to the suppression of polyQ aggregation. Based on the authors’ results, this mechanism is conserved in yeast and mammalian cells (Schlagowski et al, 2021).

To better understand how Mia40 affects polyQ aggregates, Schlagowski et al (2021) set out to explore changes in aggregate morphology. Based on fluorescence microscopy images, they noticed that polyQ formed several small and distinct aggregates in wild‐type cells. However, in the case of Mia40 excess, two types of aggregates were observed. Most of the cells had homogeneously dispersed polyQ signals, while in others, polyQ formed one large intracellular species. The authors explored this characteristic in‐depth by following the temporal and spatial patterns of the formed aggregates and their inheritance. They discovered that cells overproducing Mia40 with homogeneously distributed polyQ continue to grow well and produce new buds. Large aggregates were more toxic than the small aggregates observed in wild‐type cells and resulted in cellular growth arrest. However, since these large deposits were outnumbered by cells with homogeneously distributed polyQ, overall Mia40 excess was effective in extending cell survival of polyQ containing cells. Based on the authors’ observations, the formation of large polyQ aggregates is a stochastic process. It will be interesting to explore further the two possible mechanisms of aggregation and their dependence on Mia40 levels. It is worth mentioning that very high levels of Mia40 are toxic for the cell and perhaps cells with such levels preferentially form large aggregate deposits.

Schlagowski et al (2021) further attempted to understand how Mia40 expression can protect cells against the formation of toxic polyQ aggregates. The authors found altered levels of prion‐like protein Rnq1 in the cells with Mia40 excess. Newly prepared strain with Mia40 excess was characterized by insoluble Rnq1 and in turn toxicity of polyQ aggregates was not suppressed. With time, Mia40 expression led to the presence of Rnq1 soluble fraction and consequently less polyQ aggregates. Thus, the mechanism of aggregate handling might be further explored with consideration of the prions and proteins that in general serve as aggregate seeds.

In their work, Schlagowski et al (2021) discovered an important link between mitochondrial protein import performance and cytosolic protein aggregation. They demonstrate that more efficient protein import reduced the polyQ aggregates and the cytosolic burden on proteostasis. This finding adds another mechanism that justifies the importance of cellular homeostasis to control levels of mitochondrial precursor proteins in the cytosol and to clear their excess. Interestingly, recent studies propose that the consequence of failures in this clearance comes with a cost of an aggregation snowball effect, in which aggregation of mitochondrial precursor proteins stimulates aggregation of other cytosolic proteins, including those that serve as models for neurodegenerative processes (Nowicka et al, 2021). The study by Schlagowski et al (2021) is an important addition to a discovery of a complex and fascinating cellular network aiming at balancing the cytosolic amount of mitochondrial proteins prior to their import to maintain cellular proteostasis. This study also provides an interesting strategy of boosting protein import into mitochondria on the cellular levels in order to inhibit the progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

The EMBO Journal (2021) 40: e109001.

See also: AM Schlagowski et al (August 2021)

References

- Boos F, Kramer L, Groh C, Jung F, Haberkant P, Stein F, Wollweber F, Gackstatter A, Zoller E, van der Laan Met al (2019) Mitochondrial protein‐induced stress triggers a global adaptive transcriptional programme. Nat Cell Biol 21: 442–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T, Park SH, Zhao L, Hartl FU, Neupert W (2017) Cytosolic protein Vms1 links ribosome quality control to mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis. Cell 171: 890–903.e18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbadia J, Brielmann RM, Neto MF, Lin YF, Haynes CM, Morimoto RI (2017) Mitochondrial stress restores the heat shock response and prevents proteostasis collapse during aging. Cell Rep 21: 1481–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martensson CU, Priesnitz C, Song J, Ellenrieder L, Doan KN, Boos F, Floerchinger A, Zufall N, Oeljeklaus S, Warscheid Bet al (2019) Mitochondrial protein translocation‐associated degradation. Nature 569: 679–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka U, Chroscicki P, Stroobants K, Sladowska M, Turek M, Uszczynska‐Ratajczak B, Kundra R, Goral T, Perni M, Dobson CMet al (2021) Cytosolic aggregation of mitochondrial proteins disrupts cellular homeostasis by stimulating the aggregation of other proteins. bioRxiv 10.1101/2021.05.02.442342 [PREPRINT] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfanner N, Warscheid B, Wiedemann N (2019) Mitochondrial proteins: from biogenesis to functional networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20: 267–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlagowski AM, Knöringer K, Morlot S, Sánchez VA, Flohr T, Krämer L, Boos F, Khalid N, Ahmed S, Schramm Jet al (2021) Increased levels of the mitochondrial import factor Mia40 prevent the aggregation of polyQ proteins in the cytosol. EMBO J 10.15252/embj.2021107913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladowska M, Turek M, Kim M‐J, Drabikowski K, Mussulini BHM, Mohanraj K, Serwa RA, Topf U, Chacinska A (2021) Proteasome activity contributes to pro‐survival response upon mild mitochondrial stress in Caenorhabditis elegans . PLoS Biol 19: e3001302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino V, Romani M, Mouchiroud L, Beck JS, Zhang H, D'Amico D, Moullan N, Potenza F, Schmid AW, Rietsch Set al (2017) Enhancing mitochondrial proteostasis reduces amyloid‐beta proteotoxicity. Nature 552: 187–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen XJ (2015) A cytosolic network suppressing mitochondria‐mediated proteostatic stress and cell death. Nature 524: 481–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidberg H, Amon A (2018) MitoCPR‐A surveillance pathway that protects mitochondria in response to protein import stress. Science 360: eaan4146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel L, Topf U, Bragoszewski P, Wiese S, Sztolsztener ME, Oeljeklaus S, Varabyova A, Lirski M, Chroscicki P, Mroczek Set al (2015) Mistargeted mitochondrial proteins activate a proteostatic response in the cytosol. Nature 524: 485–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]