Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of acute endophthalmitis and hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon associated with ocular toxocariasis.

Observations

An immunocompetent 56-year-old woman presented to our hospital with a sudden onset and a three-day history of decreased visual acuity in her left eye. There were no known inciting factors for her symptoms; however, she had a history of eating undercooked beef five days prior. On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity of her left eye was light perception and the intraocular pressure was 24 mmHg. Hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon and vitreous opacity suggestive of acute endophthalmitis were observed in her left eye. The patient underwent an emergency pars plana vitrectomy. The intraoperative findings included iridodialysis, severe vitritis, multiple whitish spots on the retina, white sheathed retinal vessels, and whitish peripheral granuloma. The aqueous humor tap and vitreous tap cultures were negative. Blood tests showed elevated eosinophil and total immunoglobulin (Ig) E levels. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of her intraocular fluid showed positive anti-Toxocara canis IgG reactions; the patient was therefore diagnosed with ocular toxocariasis. Subsequent treatment with oral albendazole and prednisone resulted in significant improvement and recovery of visual acuity to 20/12.5.

Conclusions and Importance

Acute endophthalmitis with hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon is a rare clinical presentation of ocular toxocariasis. The findings from this case highlight the importance of suspecting ocular toxocariasis if a patient presents with acute endophthalmitis and hyphema accompanied with peripheral granuloma. Early vitrectomy and subsequent treatment with oral albendazole and prednisone can be effective in visual recovery.

Keywords: Ocular toxocariasis, Toxocara canis, Acute endophthalmitis, Pink hypopyon, Vitreous opacity, Peripheral granuloma

1. Introduction

Toxocariasis is an infectious disease caused by Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati.1,2 The larvae of the Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati migrate to various organs, including lungs, liver, heart, brain, kidney, skin, and eyes.2 Two main forms of human toxocariasis have been established based on the place of migration and the associated clinical manifestations, namely: visceral larva migrans (VLM) and ocular toxocariasis (OT).3 Human toxocariasis is further classified into four types: VLM, OT, covert toxocariasis, and neurotoxocariasis.4, 5, 6, 7

OT is an intraocular infection.4,5 The typical presentation of OT includes posterior pole granuloma,8,9 peripheral granuloma,10, 11, 12, 13 and chronic endophthalmitis.8,14 However, no case of acute endophthalmitis with hyphema associated with OT has been reported till date. In this report, we present the details of a rare case of acute endophthalmitis with hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon as the initial manifestations of ocular toxocariasis, which was successfully treated with early vitrectomy followed by oral administration of albendazole and prednisone.

2. Case report

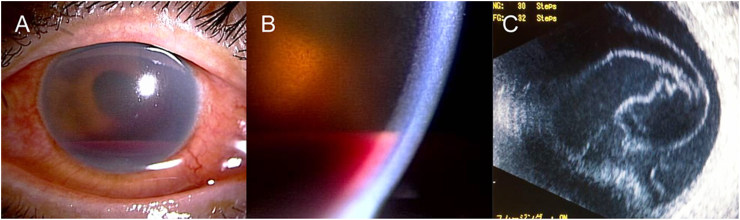

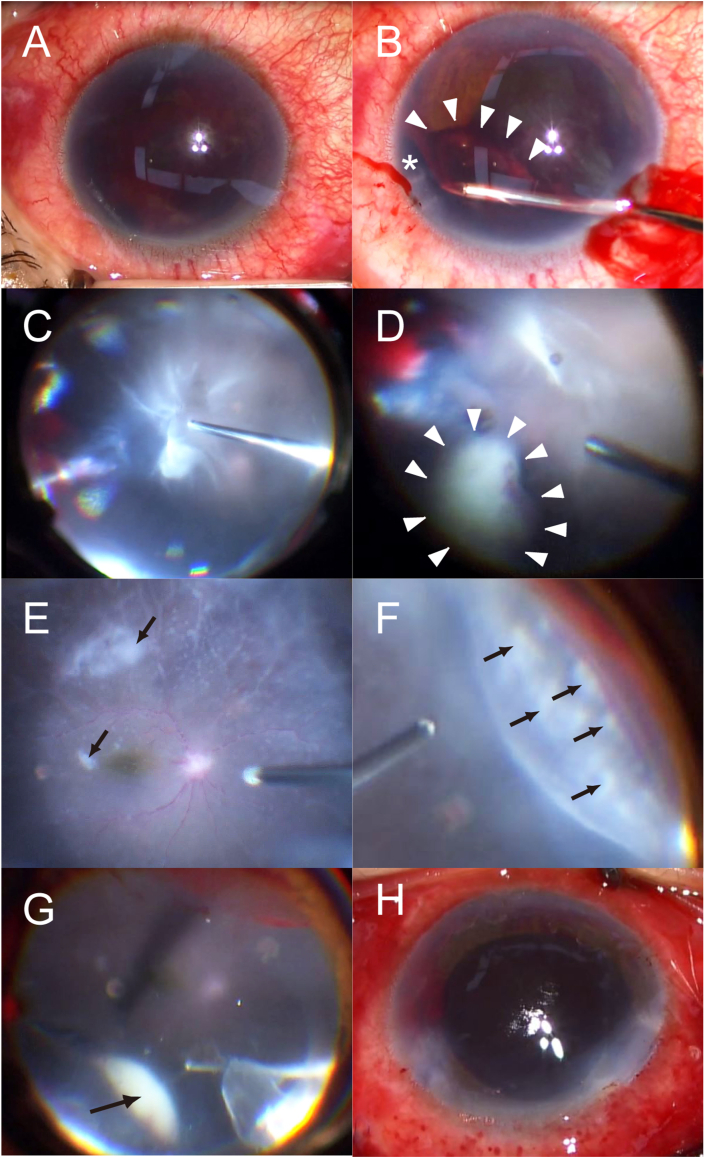

A healthy, immunocompetent 56-year-old woman presented to our hospital with a sudden onset and a three-day history of decreased visual acuity, blepharoptosis, and eyelid swelling in her left eye (OS). There were no known inciting factors for her symptoms; however, the patient had a history of eating undercooked beef that she cooked herself five days prior. She had been using anti-glaucoma eyedrops including tafluprost, timolol, and brinzolamid for the treatment of primary open-angle glaucoma. Her best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) during her regular follow-up for glaucoma prior to the onset of the decreased visual acuity was 20/12.5 OS. She had no other ocular or general medical history. Her body temperature was 37.0 °C at the time of examination. On examination, the BCVA for her OS was light perception and the intraocular pressure was 24 mmHg. Pink colored hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon and diffuse conjunctival injection were observed on anterior segment examination (Fig. 1A and B). A dense vitreous opacity suspected to be suggestive of acute endophthalmitis was observed on B-scan ultrasonography (Fig. 1C). The patient underwent an emergency 25-gauge pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with phacoemulsification and aspiration. The intraoperative findings included hemorrhage in the anterior chamber and vitreous due to iridodialysis, a thick fibrin membrane anterior to the iris, severe vitritis, whitish peripheral granuloma protruding toward the vitreous cavity, multiple whitish spots on the entire retina, and non-perfused white sheathed retinal vessels mimicking septic emboli (Fig. 2). The anterior chamber tap and vitreous tap cultures were negative. Histopathological examination revealed no malignant cells in the vitreous sample. Chest and abdominal computed tomography findings were normal. There were no signs suggestive of uveitis due to tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasma, fungus, or viral infection. Blood test results showed elevated levels of total immunoglobulin (Ig) E (2385.1 IU/mL). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of intraocular fluid collected three days after the PPV showed positive anti-Toxocara canis IgG reactions, with an optical density (OD) value of 0.37 (positive control, 1.507; negative control, 0.062) (Fig. 3). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with OT. Western blotting for the detection of serum anti-Toxocara canis IgG returned negative results.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative images of the left eye of a 56-year-old woman with ocular toxocariasis at initial presentation. (A) Slit-lamp photograph. (B) Magnified image of a slit-lamp photograph showing hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon. (C) B-scan ultrasonography image showing vitreous opacity indicative of endophthalmitis. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative images obtained during pars plana vitrectomy and phacoemulsification and aspiration. (A) Image of the anterior segment at the beginning of surgery. (B) Removal of the hemorrhage and the fibrin membrane anterior to the iris using capsule forceps. Iridodialysis (*) was identified during surgery. (C) Three port 25-gauge vitrectomy. Wide-viewing system shows hemorrhage originating from iridodialysis and severe vitritis. (D) Whitish peripheral granuloma (white arrowheads) protruding toward the vitreous cavity. (E) Whitish spots on the retina (black arrows) and non-perfused white sheathed retinal vessels mimicking septic emboli. (F) Whitish spots on the peripheral retina (black arrows). (G) Whitish peripheral granuloma under scleral depression (black arrow). (H) Image of the anterior segment at the end of surgery. Posterior capsulotomy was performed. The intraocular lens was not implanted.

Fig. 3.

Intraocular fluid collected for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay three days after pars plana vitrectomy.

The patient was treated with oral albendazole and prednisone at day 12 postoperatively after diagnosis of OT. Albendazole (600 mg daily) was administered for 75 days and prednisone (initial dose 20 mg/day) was gradually tapered over the next five months. The BCVA of the OS improved to hand motion on postoperative day 1, 20/100 on day 8, 20/32 on day 10, 20/20 on day 16, and 20/12.5 on day 47.

Hemorrhage due to iridodialysis did not recur after surgery. The whitish peripheral granuloma, which protruded towards the vitreous cavity, gradually decreased and remained as an atrophic lesion without protrusion (Fig. 4). The multiple whitish spots on the retina completely disappeared. The white sheathed retinal vessels reperfused without permanent occlusion. Because the patient was aphakic after the phacoemulsification and aspiration, the patient underwent sulcus-fixated secondary implantation of a three-piece intraocular lens 15 months after the initial surgery. At the last examination 18 months after the initial surgery, the patient's BCVA was 20/12.5 in the OS with no evidence of inflammation (Fig. 4). Her right eye had a visual acuity of 20/12.5 and was unremarkable throughout the follow-up.

Fig. 4.

Post-operative images. (A) Slit-lamp photograph eight days after pars plana vitrectomy (PPV). (B) Wide-field fundus photograph eight days after PPV. Whitish peripheral granuloma (white arrow) protruding toward the vitreous cavity is still observed. (C) Swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) image eight days after PPV. (D) Slit-lamp photograph two weeks after PPV. (E) Wide-field fundus photograph two weeks after PPV. (F) Fundus photograph two weeks after PPV. (G) SS-OCT image two weeks after PPV. (H) Slit-lamp photograph 18 months after PPV. Secondary intraocular lens implantation was performed 15 months after PPV. The patient's visual acuity improved to 20/12.5 OS. (I) Wide-field fundus photograph 18 months after PPV. Whitish peripheral granuloma is no longer observed. Atrophic scar is observed in the former position of the peripheral granuloma. (J) Fundus photograph 18 months after PPV. (K) SS-OCT image 18 months after PPV shows normal macular structure.

3. Discussion

In this report, we presented the details of a rare case of acute endophthalmitis with hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon as the initial manifestations of ocular toxocariasis. Acute cases of endophthalmitis are usually caused by gram-positive bacteria postoperatively.15 However, the patient in the present case had no history of intraocular surgery or a general condition that may have made her susceptible to endogenous endophthalmitis. Therefore, we could not diagnose OT before the surgery. However, the whitish protrusion of the peripheral granuloma detected during surgery strongly suggested an OT diagnosis in the present case.10, 11, 12, 13 The elevated levels of IgE in the blood also provided supplementary evidence that suggested a diagnosis of OT.16

Although chronic endophthalmitis has been reported in two-to eight-year old children who have OT,8,14 to the best of our knowledge, the present case is the most acute case of endophthalmitis associated with OT reported till date. The visual acuity of the patient decreased to light perception within three days. In addition, although hypopyon has been reported in severe cases of OT, pink colored hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon has not been reported in cases of OT.17 Several reports have demonstrated an association between certain bacterial species, such as Serratia marcescens and Klebsiella pneumonia, and pink hypopyon.18,19 The pink color of the hypopyon is derived from the bacterium producing red pigment (prodigiosin). The patient in the present case had severe inflammation and hemorrhage from iridodialysis corresponding to the location of the peripheral granuloma, resulting in pink colored hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon potentially due to coexistence of red blood cells and leukocytes.

Assay of antibodies against Toxocara canis returned positive results for intraocular fluid but negative results for serum, indicating the intraocular synthesis of IgG in the present case. Some reports have described cases of OT with positive anti-Toxocara IgG antibodies only in aqueous or vitreous samples but not in sera.20,21 OT is caused by ingesting embryonated eggs from soil and water or by eating raw meat containing infective larvae.2 It is uncertain whether eating undercooked meat five days prior to the clinical visit was responsible for the acute presentation of OT in the present case. However, the patient had no history of contact with dogs or cats and no meat-eating habits. In addition, she had no history of uveitis during a regular ophthalmological examination for glaucoma. The meat the patient consumed five days prior to her clinical visit was the first she had consumed in two years, suggesting that meat-derived larvae were the probable sources of OT in the present case.

It has been reported that most patients who have OT experience permanent ocular damage by the time they are seen by an ophthalmologist.22 However, in the present case, treatment with vitrectomy followed by combination therapy with oral albendazole and prednisone rapidly and significantly improved the patient's visual acuity from light perception to 20/20 in 16 days after the surgery. The visual acuity further recovered to 20/12.5 in 47 days. Although signs of extensive inflammation, such as vitreous opacity, multiple whitish spots on the retina, and white sheathed retinal vessels, were observed during surgery, those acute inflammatory reactions, possibly towards highly immunogenetic larval antigens, were reversed without permanent damage to the intraocular tissue. Performing vitrectomy to remove the larval antigens and administration of prednisone to reduce the inflammatory reaction seems to be theoretically effective in resolving the severe inflammation associated with OT and in improving vision.23, 24, 25

4. Conclusions

In this report, we presented the details of a case of acute endophthalmitis with hyphema mimicking pink hypopyon associated with OT. The findings of this case highlight the importance of suspecting OT if a patient presents with acute endophthalmitis and hyphema accompanied with peripheral granuloma. Early vitrectomy and subsequent treatment with oral albendazole and prednisone can be effective in improving vision in such cases.

Patient consent

Consent to publish the case report was not obtained. This report does not contain any personal information that could lead to the identification of the patient.

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Intellectual property

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

Research ethics

We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

Authorship

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

- 1.Beaver P.C., Snyde C.H., Carrera G.M. Chronic eosinophilia due to visceral larva migrans. Pediatrics. 1952;9(1):7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Despommier D. Toxocariasis: clinical aspects, epidemiology, medical ecology, and molecular aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(2):265–272. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.265-272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor M.R., Keane C.T., O'Connor P., Mulvihill E., Holland C. The expanded spectrum of toxocaral disease. Lancet. 1998;1(8587):692–695. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilder H.C. Nematode endophthalmitis. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1950;55:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields J.A. Ocular toxocariasis. A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28(5):361–381. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathwani D., Laing R.B., Currie P.F. Covert toxocariasis--A cause of recurrent abdominal pain in childhood. Br J Clin Pract. 1992;46(4):271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvador S., Ribeiro R., Winckler M.I., Ohlweiler L., Riesgo R. Pediatric neurotoxocariasis with concomitant cerebral, cerebellar, and peripheral nervous system involvement: case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr. 2010;86(6):531–534. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duguid I.M. Features of ocular infestation by Toxocara. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45(12):789–796. doi: 10.1136/bjo.45.12.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashton N. Larval granulomatosis of the retina due to Toxocara. Br J Ophthalmol. 1960;44(3):129–148. doi: 10.1136/bjo.44.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irvine W.C., Irvine A.R., Jr. Nematode endophthalmitis: Toxocara canis: report of one case. Am J Ophthalmol. 1959;47:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)78242-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greer C.H. Toxocara infestation of the eye. Trans Ophthalmol Soc Aust. 1963;23:90–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogan M.J., Kimura S.J., Spencer W.H. Visceral larva migrans and peripheral retinitis. J Am Med Assoc. 1965;194(13):1345–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson C.P., Welch R.B. Lntraocular Toxocara. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71(4):921–930. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)90267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duguid I.M. Chronic endophthalmitis due to Toxocara. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45(11):705–717. doi: 10.1136/bjo.45.11.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han D.P., Wisniewski S.R., Wilson L.A. Spectrum and susceptibilities of microbiologic isolates in the endophthalmitis vitrectomy study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71959-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jee D., Kim K.S., Lee W.K., Kim W., Jeon S. Clinical features of ocular toxocariasis in adult Korean patients. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2016;24(2):207–216. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2014.994783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith P.H., Greer C.H. Unusual presentation of ocular Toxocara infestation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1971;55(5):317–320. doi: 10.1136/bjo.55.5.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.al Hazzaa S.A., Tabbara K.F., Gammon J.A. Pink hypopyon: a sign of Serratia marcescens endophthalmitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(12):764–765. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.12.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chao A.N., Chao A., Wang N.C., Kuo Y.H., Chen T.L. Pink hypopyon caused by Klebsiella pneumonia. Eye. 2010;24(5):929–931. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felberg N.T., Shields J.A., Federman J.L. Antibody to Toxocara canis in the aqueous humor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(9):1563–1564. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930020437005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fomda B.A., Ahmad Z., Khan N.N., Tanveer S., Wani S.A. Ocular toxocariasis in a child: a case report from Kashmir, north India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25(4):411–412. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.37352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woodhall D., Starr M.C., Montgomery S.P. Ocular toxocariasis: epidemiologic, anatomic, and therapeutic variations based on a survey of ophthalmic subspecialists. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(6):1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maguire A.M., Green W.R., Michels R.G., Erozan Y.S. Recovery of intraocular Toxocara Canis by pars plana vitrectomy. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(5):675–680. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagler W.S., Pollard Z.F., Jarrett W.H., Donnelly E.H. Results of surgery for ocular Toxocara canis. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(10):1081–1086. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(81)80039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belmont J.B., Irvine A., Benson W., O'Connor G.R. Vitrectomy in ocular toxocariasis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(12):1912–1915. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040892004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]