Abstract

Background

Women are underrepresented in healthcare leadership, yet evidence on impactful organisational strategies, practices and policies that advance women's careers are limited. We aimed to explore these across sectors to gain insight into measurably advancing women in leadership in healthcare.

Methods

A systematic review was performed across Medline via OVID; Medline in-process and other non-indexed citations via OVID; PsycINFO and SCOPUS from January 2000 to March 2021. Methods are outlined in a published protocol registered a priori on PROSPERO (CRD42020162115). Eligible studies reported on organisational interventions for advancing women in leadership with at least one measurable outcome. Studies were assessed independently by two reviewers. Identified interventions were organised into categories and meta-synthesis was completed following the ‘ENhancing Transparency in REporting the synthesis of Qualitative research’ (ENTREQ) statement.

Findings

There were 91 eligible studies from 6 continents with 40 quantitative, 38 qualitative and 13 mixed methods studies. These spanned academia, health, government, sports, hospitality, finance and information technology sectors, with around half of studies in health and academia. Sample size, career stage and outcomes ranged broadly. Potentially effective interventions consistently reported that organisational leadership, commitment and accountability were key drivers of organisational change. Organisational intervention categories included i) organisational processes; ii) awareness and engagement; iii) mentoring and networking; iv) leadership development; and v) support tools. A descriptive meta-synthesis of detailed strategies, policies and practices within these categories was completed.

Interpretation

This review provides an evidence base on organisational interventions for advancing women in leadership across diverse settings, with lessons for healthcare. It transcends the focus on the individual to target organisational change, capturing measurable change across intervention categories. This work directly informs a national initiative with international links, to enable women to achieve their career goals in healthcare and moves beyond the focus on barriers to solutions.

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

There is extensive evidence on the slow progress and considerable barriers to advancing women in leadership in healthcare and academia. However, research on effective interventions to measurably facilitate change is limited.

Added value of this study

This study transcends the focus on barriers for women and what individuals need to do to address them by identifying, extracting and synthesising diverse cross-sector studies on organisational interventions for advancing women in leadership.

Implications of all the available evidence

The findings here inform a large-scale international collaboration on co-designing implementation research that translates and integrates these interventions into practice.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Despite extensive efforts across sectors, women continue to be underrepresented in leadership [1], limiting their influence and impact and hampering diversity and gender equity goals [2,3]. In the health sector, women represent 71% of the global workforce [4], [5], [6] and 59% of all medical, biomedical and health science degree graduates [7]. However, the “leaky pipeline” persists, with lower participation of women in leadership, relative to their proportion in the workforce [6]. Barriers include reduced capacity due to career disruption and external responsibilities; credibility assumptions around women in leadership and perceived capability and confidence [4,8,9]. Early career male and female doctors progress similarly, yet women are five times more likely to have family related career disruptions, profoundly impacting on career progression [10]. For women in nursing, midwifery, and allied or social care roles, the overall profession is often undervalued as ‘women's work’ [11]. Gender inequity in healthcare leadership results in loss of critical skill and experience, low morale, increased costs of sustaining the workforce, and adverse impacts on healthcare and policies affecting women and children [6,9,12,13].

A 22% increase in global human capital wealth is estimated, should equal participation of women in health be realised [6,12,13]. More broadly, increasing the potential of women as leaders is a critical long-term investment for organisational success [10,14,15], improved health policy [12,16,17] and national prosperity and quality of life [18]. More women in leadership increases organisational productivity [12,19] and maximises the value of the female workforce [6,12]. In 2021, the compelling narrative has shifted beyond the gaps, barriers and need to justify benefits of gender equity in leadership, to a clear imperative for delivering effective, sustainable improvement [18,[20], [21], [22]].

However, research continues to focus on the gaps and the barriers to women's career progression, rather than on potentially effective strategies to advance women in leadership [4,8,[23], [24], [25]]. Furthermore, where research has explored strategies in this field, these primarily focus on “fixing” the individual, rather than on addressing the organisational and systemic level challenges [4,5,10,19,26]. The European Commission [27], highlights that systemic inequities in the workforce are perpetuated by gender-based barriers stemming from organisational constraints and culture, unrelated to individual capability. Restrictive organisational norms fail to harness workforce capability by expecting women to work in a system primarily designed by and for traditional male gender roles [18] and life patterns, and are broadly detrimental to social, economic and health outcomes [13,23]. Indeed, research indicates that addressing structural issues and workplace norms at an organisational level is a necessary step [18,28]. To advance the field, research into interventions that move beyond “fixing the individual” toward organisational-level strategies and system level change is now imperative, as highlighted in The Lancet [3,4,6,8,18,26,27,29,30].

The healthcare sector, with a primarily female workforce, is currently advancing women in leadership at a glacial pace. Challenges appear intractable with limited research into effective organisational strategies that can accelerate change [12,17,31]. Prior reviews examining organisational interventions for gender equity in leadership are generally outdated, not systematic, are narrow in scope to single interventions and disciplines; and report on limited outcomes [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. In contrast, outside healthcare, interventions are often underpinned by organisational theory and practices, potentially accelerating progress and offering important learnings for healthcare [12,17,[37], [38], [39]]. Here, we aimed to capture current evidence in a rigorous systematic review across contexts, settings, disciplines and sectors, on potentially effective organisational interventions that can advance women in healthcare leadership. The findings of this work will directly inform a large-scale funded national initiative to advance women in healthcare leadership, with strong international links.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

This systematic review aligns with the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination of systematic reviews [40] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) checklist [41]. Methods are outlined in detail in a protocol registered a priori on PROSPERO (CRD42020162115) and is previously published [42]. Eligibility was based on the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICO) framework [43], with studies included if they met the following criteria: (1) examined an intervention delivered to women of any demographic characteristics and across all industries; (2) described an organizational-level intervention, implemented either in isolation or in combination with other interventions; (3) the intervention was designed specifically for advancing women in leadership and compared with any control group (different intervention, no intervention); (4) outcomes were assessed and impact reported (both quantitative and qualitative methods were included); (5) studies published in English in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2000 (coinciding with release of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals which include closing the leadership gap through women's collective action) and March 2021. We excluded studies that solely focused on the reporting of barriers or enablers related to gender equity broadly, with no interventional element or that did not include at least one outcome related to advancing women in leadership.

Searches using relevant search terms outlined in our protocol were conducted across MEDLINE via OVID; Medline in-process and other non-indexed citations via OVID; PsycINFO; and SCOPUS. Two independent reviewers (MM, AM) screened titles and abstracts for eligibility and studies that met criteria on title and abstract, underwent full text review. Here, the second reviewer completed 20% of screening and full text review, with cross checking revealing no discrepancies. Using an agreed template, data from all studies were then independently extracted by the two reviewers (MM, AM), including group sample sizes, sectors, settings, follow up duration and outcomes, along with categorising and detailing types of intervention strategy. Our aim is to capture primary outcomes on advancing women in leadership across diverse sectors, contexts and interventions.

2.2. Data analysis

2.2.1. Risk of bias and study quality

Risk of bias and study quality was assessed at study-level using the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme [CASP] tools [44]. A second reviewer (AM) assessed 20% of eligible studies with discussion of any disagreements, whereby alignment was strong and no further escalation was required for consistency. Each study was rated as high, moderate, or low risk of bias and quality against set criteria and scored at 2, 1, or 0, respectively. Individual quality items were assessed using a descriptive component approach and discussed for clarity and consensus. Planned methods included the application of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations framework (GRADE).

2.3. Meta-synthesis

As per the published protocol [42], an overarching narrative meta-synthesis was completed. The ‘ENhancing Transparency in REporting the synthesis of Qualitative research’ (ENTREQ) statement was followed [45]. Meta-synthesis intentionally avoids averaging of results, instead expanding findings from each study to construct a larger and more scalable narrative [46], linking data and conclusions, while acknowledging limitations of the literature. The goal of this meta-synthesis was to inductively generate rich and compelling insights on the processes that measurably support both individual and organisational needs and enable women to advance in healthcare leadership [47].

Initial synthesis involved categorising the interventions based on their substantive topics. Data synthesis and analysis was conducted by i) verbatim study level data extraction ii) line by line coding iii) grouping of codes into narrative descriptions; and iv) analytical theme generation with agreement across two reviewers [46,45]. The salient features of each included study were captured, and data was then coded to develop an understanding of each study, before cross-study integration. In this review, theme generation revealed the adopted categories, with study categorisation agreed across two reviewers (MM, AM), then circulated for consensus across several multidisciplinary authors (HS, JB), with the senior author (HT) making the final decision. Within each category, emergent from additional synthesis were sub-themes of organisational strategies, policies and practices, capturing practical examples. Final synthesis results were also checked against the results of the high-quality studies to ensure reported findings reflected the best quality data. Given the substantial methodological heterogeneity across sectors and fields of research, quantitative data meta-analysis was not applicable.

2.4. Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing. The corresponding author had full access to all data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. Results

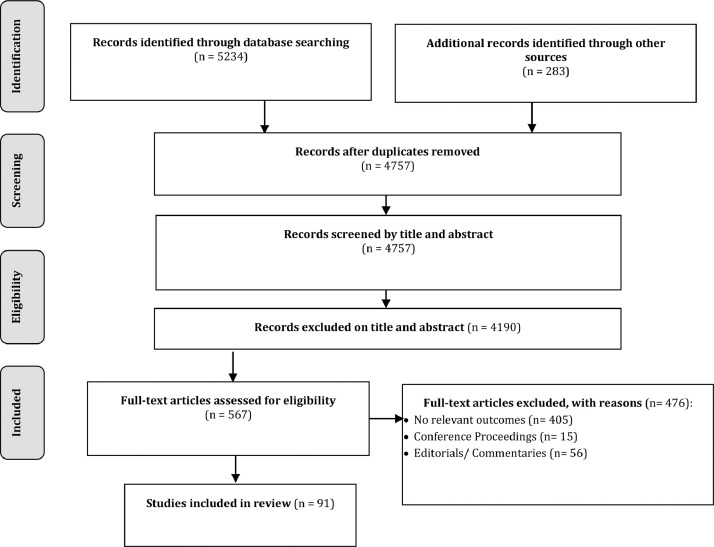

The PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1 shows 5324 articles identified on searching and screening, with 567 duplicates, leaving 4757 articles for title and abstract screening. Of these, 476 articles underwent full-text assessment and 91 met eligibility criteria and were included. Characteristics of included studies are presented in Supplementary Tables S1A and S1B, with (n = 40) quantitative, (n = 38) qualitative and (n = 13) mixed methods studies. Five were quantitative RCTs, 26 observational, eight pre-post assessments and one experimental simulation (Table S1A). Qualitative studies included interviews, focus groups or case studies and interpreted results within phenomenological, grounded, narrative, and critical frameworks (Table S1B). Sample sizes ranged from 4 to 63,539 individuals or responses and involved diverse populations across different career stages and positions. Most studies (89%) were published in the last 10 years and were conducted in the US (n = 41), the UK (n = 8), Europe (n = 7), Canada (n = 3) or other countries (Tables S1A, S1B). Some were global (n = 4) or multinational (n = 5). Sectors included academic medicine and academia (n = 26), business and manufacturing (n = 19) and healthcare (n = 13), with government, sports and banking/finance also examined (Tables S1A, S1B). Outcomes were diverse and are presented in Tables S1A and S1B. Five categories of strategies, policies or practices emerged and are captured in Table 1. They include: (i) organisational processes; (ii) awareness and engagement; (iii) mentoring and networking; (iv) leadership development; and (v) support tools. Risk of bias varied significantly, and was considered when comparing findings and rating evidence quality. Individual study risk of bias assessment is presented in Table S2. Overall, 14% of studies were rated as high risk, 47% moderate and 39% low risk of bias.

Fig. 1.

Study selection.

Table 1.

Summary of overall strategies across categories for advancing women in leadership.

| Category | Concept | Summary of strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Organisational Processes (37 studies) | Leadership commitment and accountability |

|

| Work-life integration |

|

|

| Reporting and enforcement mechanisms |

|

|

| Gender bias elimination |

|

|

| Awareness and Engagement (10 studies) | Awareness and Improvement culture |

|

| Organisational Role Modelling |

|

|

| Inclusion and diversity |

|

|

|

Mentoring and Networking (14 studies) |

Formal and Informal approaches |

|

|

Leader Training and Development (15 studies) |

Design and approach |

|

| Content elements |

|

|

| Support tools (15 studies) | Recruitment, Retention and Promotion | Recruitment:

|

| Measurement and Evaluation |

|

3.1. Category 1 – organisational processes

The majority of the studies were in this category. Organisational leadership commitment and accountability emerged as vital in sanctioning and driving organisational change [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]. Gender balance in leadership and performance was enhanced by addressing structural barriers such as career flexibility and family-friendly policies [53], [54], [55]. In multi-source, multi-wave randomised control trials , addressing gender bias was critically dependent on manipulation of gender composition, at all levels of the organisation, ensuring equal representation and a fair playing field [56]. Family-friendly policies and incentives were noted to assist women with work-life integration, particularly where policy awareness was high [53,[57], [58], [59]] or when strategies were actively implemented [53,59]. Flexible work policies and ‘soft’ regulation such as a code of conduct, improved women's career advancement (e.g. parental leave, duty flexibility). Promotion, awareness and implementation of policies that support women, decreased barriers and improved commitment, engagement and attitudes towards organisational efforts [48,50,53,57,[59], [60], [61]]. Providing support and incentives to address organisational career barriers for women across early, mid and late career stages was useful [62,63] in improving overall culture, psychological well-being, and career and health outcomes [4,53,58,[63], [64], [65], [66]]. Effective succession and retention practices included introducing flexible meeting design (in structure, setup and conduct), increasing remuneration strategies that overtly enable and fund participation of women, and promoting female role models [49,52,[67], [68], [69]]. Supportive human resource policies and practices also influenced attitudes towards promotion of women [61], with organisational support critical in mitigating the impact of career inflection points or transitions [63]. Specifically, in healthcare, health professionals noted the impact of career inflections points was more pronounced at early career stages for those in clinical roles, while those in management roles experienced greater impact of career inflections later [63].

Regulatory actions were more beneficial when they involved explicit goals (i.e., targets and quotas) supported by enforcement mechanisms, compared to reporting requirements alone [70,71]. Hard sanctions for non-compliance further improved outcomes [70], especially when balanced with support strategies and ‘soft’ regulatory action (e.g. corporate strategy or code of conduct) to promote sustainable cultural change for gender equity [70,72]. Combined, these strategies improved attitudes and behaviours towards gender equity, creating an improved work environment and increasing productivity [65,66,70,71,[73], [74], [75]]. Here, the majority of studies indicate that a strong supportive culture that offers opportunities for women to broaden their experience and nurture their leadership potential, advanced women in leadership [76,56,77]. However, observations across sectors showed that this achieved little in isolation, without objective assessment, evaluation and feedback on performance and fairer appointment and succession policy and practices [73,78].

3.2. Category 2 – awareness and engagement

Publicising and promoting organisational challenges in gender equity and of policies and practices were helpful in building a culture of awareness, workforce engagement, opportunity and motivation (Tables S1A, S1B). Promotion of family-friendly approaches that mitigated the impacts of family demands [79], [80], [81] and reduced bias from gender role stereotypes [77], improving perceptions of women's leadership efficacy and fostering a culture supportive of advancing women in leadership [53,54,59]. Improved awareness of strategies that address gender bias, promoted organisational equity [77], mitigated backlash and enhanced ally-ship (the extent to which men advocate for women) [82]. Studies indicated that increasing women in leadership enhanced awareness, engagement, knowledge, attitudes, support and beliefs around gender equity [82]. The use of women-focused metaphors (e.g. glass-cliff) shifted the focus to changing the situation for women, as opposed to changing individual women [83]. Engagement initiatives focusing on individuals’ actions, instead of on avoidant behaviours, reduced self-reported gender bias, positively framing gender equity and increasing motivation for ally-ship [77,82]. In turn, this improved workplace inclusivity and job satisfaction, and lowered intentions to turnover [77,82].

Coupling these initiatives with gender diversity/ inclusivity training prompted participatory behaviours amongst employees, and challenged non-inclusive behaviours, compared to controls [82,84]. Exposure to counter-stereotypical models of leadership, ascribing both agency and communality to women (women as capable of being assertive and strong, as well as caring and supportive) altered perceptions and judgement, and enhanced awareness and diversity, challenging the traditionally proto-typical masculine concept of leadership [84], [85], [86], [87]. Overall, preventing ‘resistance’ in organisational culture required concerted effort to maintain the premise of merit and individual advancement. Sensitising the workforce to the challenge's women face and highlighting the personal impact of gender inequity on the individual was important [56,64]. Effecting positive change required workforce engagement in co-design and action-focused solutions that apply ‘new’ knowledge in practice, while managing expectations and fostering resilience when set-backs occur [56,64].

3.2.1. Category 3 – mentoring and networking

Formal mentoring programs improved women's ability, skills and productivity, with women in junior and senior positions equally likely to become mentors [88]. Job sharing provided opportunity for women to enact leadership in part work, play to one another's strengths and shoulder complexity and responsibility together [75]. This created a key network connection and made leadership roles more tenable [75], and occupational socialisation and adjustment more achievable. Network composition was related to promotions and network status (the extent individuals had network connections and held high-ranking jobs) [89], [90], [91]. Women benefitted from networks with high status male members [89]. Conversely, networks with more women were associated with fewer promotions for women [89]. Male allies perceived mentoring as significant in supporting women's leadership, when coupled with sponsorship to recognise and promote women into leadership [51,92]. Overall satisfaction with network participation was highest for women in entry and early-mid career positions, who reported more mentoring, expanded opportunities, and increased work engagement [89,91].

3.3. Category 4 – leadership development

All relevant studies reported that developing organisational leadership and ability supported women's careers (Tables S1A, S1B), enhancing skills, attitudes and behaviours including expanding participation in broader activities and networks [86,[93], [94], [95]]. Content included learning to ‘survive and thrive’ in male dominated contexts, building support, overcoming barriers, and career consolidation [96]. Mixed and women-only programs were potentially effective, with the latter also creating safe spaces for connection and social learning [97]. Satisfaction with leadership programs correlated strongly with role engagement [95], with most reporting positive experiences, increased leadership competencies, newly created networks, enhanced interactions and a supportive community of practice [94,95,[97], [98], [99],100]. Organisations benefitted from demonstrating commitment, which enhanced participant willingness and ability to understand how to navigate the workplace [94,95,98,99,101], also improving attitudes, engagement and retention [86,102,103]. Improved retention, professional growth, capacity and engagement in mentoring others was also noted [93,103] alongside leadership advancement [93,100,104]. One study showed program completers were more likely to be retained by their workplace compared to non-completers, meanwhile for minority ethnic groups, both retention and promotion rates improved [100]. Increased capability and heightened awareness of unconscious bias and organisational mitigation strategies, encouraged women's self-efficacy and reduced counter-productive thinking and behaviours that hinder leadership potential [86,102,104].

3.4. Category 5 – support tools

Multifaceted tools (e.g. models, frameworks, measures) that described specific gender-related problems or issues to be addressed, and explored why and for whom a concern was of importance, providing a logic for taking one particular approach over another comprised this category [78,100,105]. Examples included providing a measure for cultural support in an organisation [105], assessing leader bias [106], framing professional development [107], and approaches for factors influencing career advancement [108,109,110,111]. Tools were applied within and across organisations and sectors, and enabled measurement of the impact of organisational interventions on advancing women in leadership [105,106,108,112]. Computational modelling tools demonstrated that gender differences in hiring, and bias in development opportunities increased turnover rates in women, with a heightened sense of tokenism and a lack of promotion [55]. Moreover, it showed that the representation of women in leadership (across all levels) varied independently to hiring rates, instead it related to leadership opportunities [55]. Tools were also useful to highlight problematic organisational practices [109], such as the disproportionate load placed on women to fulfil career requirements, and negative impacts of obstacles to accessing initiatives [109]. Priority setting tools [113] guided organisational implementation of strategies, whilst use of a support paradox framework, focused organisational effort on promoting cultural acceptance of women in leadership [92,114]. For successful implementation and sustainability, organisational-level gender equity support tools needed commitment and accountability of senior leadership, regardless of their gender [111]. Alternatively, tools and frameworks success was undermined, where wider organisational practices and policies lacked a gender equity agenda [109], by complexity and by contextual variables that made adaptation to moving targets and conditions more challenging [110].

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-synthesis to identify, extract and synthesise evidence on organisational interventions that measurably advance women in leadership, from within and beyond the healthcare sector. This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines and applies the CASP framework. Meta-synthesis is based on ENTREQ guidelines, and informed the analytical approach. Overall, 91 studies across 13 countries and 16 sectors were included, with almost half from health and academia. Studies were highly heterogeneous in design, setting, intervention, outcomes, career stage and quality. Leadership commitment and culture change were important, delivered through strategies, policies and practices captured across five emergent categories; organisational processes, awareness and engagement, mentoring and networking, training and development, and organisational support tools. Narrative meta-synthesis generated further insights within these categories for the measurable advancement of women in leadership.

Organisational processes were the prevalent interventions, aiming to overcome well established barriers that perpetuate cultural norms and hinder women's career advancement [13,[33], [34], [35], [36], [37],56,115,116]. Leadership commitment and accountability were critical in sanctioning and championing these policies and practices, building a positive culture to deliver opportunity and optimise motivation for women [117,[48], [49], [50], [51], [52],50,[52], [53], [54]]. Optimising work-life integration; active and transparent support for gender equity in leader selection and promotion; structured opportunities for formal and informal professional development; equal access to resources; fairness in processes; and elimination of gender- bias were all effective [13,[33], [34], [35], [36], [37]]. Similarly, increasing numbers and visibility of women at all levels of leadership, enhanced motivation and opportunity for other women, further enhanced by support and advocacy from men [56,115,116]. Despite being unpopular across genders [18], quotas and targets improved career advancement [12,118], especially when supported by robust reporting [18]. Alignment of gender equity policies with practices, improved organisational culture, enabled women to feel supported and respected and validated leadership aspirations, including in healthcare [18]. Whilst cross sector learnings here are useful, further research is needed specifically in the context of healthcare where traditionally masculine perspectives of leadership and hierarchical cultures still prevail [56,115,116].

Workforce engagement and promoting awareness of gender barriers and their impact, alongside organisational mitigation strategies are important in advancing women in leadership [18,53,[119], [120], [121]]. These barriers include perceptions that women's underrepresentation in leadership is trivial [68,122] or ‘natural’, given women's caring roles [4], and career interruptions which limit leadership motivation and opportunity [76]. Actively promoted organisational strategies generated stronger organisational culture (e.g. improved socialisation and integration of women) and delivered individual benefits (e.g. provision of opportunities and access to resources) [76,115,116]. Tackling organisational social and cultural mechanisms is important and requires effort to generate and sustain an engaged culture of work and life centrality, improving women's self-confidence and determination to achieve career objectives [22,53,58,79,122]. Isolated short-term initiatives, even when well resourced, can be unsustainable and fail to be embedded within organisations [107,123].These types of efforts can be counter-productive, invite resentment in some employees, and can hinder progress in gender equity [107,124]. Sustained success requires clear roles and responsibilities across an organisation, regardless of gender, in supporting and advocating for women [18]. In healthcare, this will require a fundamental shift in culture, with commitment and accountability of leadership towards change [125], [126], [127], [128]. Future research is needed to gain greater insight into organisational cultures in the strongly hierarchical healthcare sector and to understand the transferability of these cross-sector learnings.

Support for women with formal and structured as well as informal and unstructured mentoring enhances opportunities for access to senior positions across sectors, including in healthcare [78,89,96,108,112,129]. Organisations that enable individuals to transfer experiences and learnings to the collective, improve their talent retention, reputation, and learnings, generating a better equipped workforce [130], [131], [132]. Mentoring was reported as most effective when the relationship between mentor and mentee formed in a natural, organic and non-contrived way within a network of genuine supporters [96,133,134]. Overall, in healthcare, mentoring has an important role to play in increasing awareness of career barriers, improving motivation for organisational change, and is often successful when linked to strategies to improve patient outcomes [90,135,136]. Evidence for networking was more variable [89], [90], [91]. Women only networks are often small and homogenous, with strong relationships but less influence and career opportunities [91,123]. Men's networks are broader, diverse, and more influential, with weaker relationships, and more focus on career mobility [137]. Women participating in networks showed benefits that support the need for diverse networks that include influential, key decision-makers and men, alongside redressing organisational constraints that perpetuate a male-dominant culture [89,91,138]. The overall lack of intervention studies on optimal networking for women is notable and supports further research in this field.

On leadership development, organisational leadership training and development programs focused on optimising capability, showed short and long-term benefits for advancement of women in leadership, including in healthcare [88,93,94,139,140]. Leadership development programs offer demonstrable value in enhancing individual capability and confidence and enhancing individual attainment of career goals, especially with continued guidance and support [94,98,139,141]. Whilst advancing organisational outcomes such as workforce engagement and socialisation is possible, [94,98,141,142] when used in isolation, these programs may fail to advance gender equity at an organisational level, and need to be supported by other additional strategies. For example, co-design of programs was useful in identifying organisational priorities and improving career opportunities and prospects [94,95,98,99,101]. Overall, cross-sector evidence did support the premise that leadership development programs are beneficial as part of organisational culture change [86,95,103,141,143], but require resources, action plans and measurable outcomes [98,103,[144], [145], [146]]. For the healthcare sector, such programs have the potential to improve the core skills, competencies and abilities of those in leadership roles, while reinstating the importance of organisational culture towards enhancing gender equity. In implementing embedded, affordable, evidence-based, co-designed and effective leadership development programs in healthcare, the aim would be to improve both individual and organisational objectives in gender equity. Implementation would require reducing often disproportionately high program costs and improving generally inadequate evaluation. Considerations of organisational culture, context and broader organisational strategies is also needed alongside leadership development program evaluation in capturing organisational change and impact [8,35].

In terms of support tools, numerous models, measures and frameworks that support gender equity goals are widely used and are useful for identifying the extent to which organisational culture is conducive to women's success [78,100,105]. Tools can highlight gender bias [106]; frame professional development of women from a systems perspective [107]; and report on individual, organisational and family-related factors in career advancement [108,109]. However, implementation of these tools can be undermined by inadequate methods; inconsistent success outcome variables; an overreliance on self-reporting and a lack of underpinning organisational theory. Again, in isolation these tools have limited impact and can paradoxically reinforce gender barriers [109]; for instance the impact of implementing gender quotas, important in creating opportunities for women [146], may incite resistance from both genders with perceptions of reverse discrimination and loss of individual merit and quality [146]. Multilevel frameworks and approaches incorporating support tools, within the context of broader organisational strategies, are needed to facilitate organisational level culture change around gender equity, including in healthcare, to advance women in leadership.

As with all systematic reviews, this work is limited by the quality of the underlying studies. Heterogeneity across discipline-specific approaches; theory application, study design and methods; objectives and outcomes; and a focus on isolated strategies were all noted. Participants characteristics, such as ethnicity and age were homogenous across studies. Most interventions were occurring in organisations already committed to gender equity efforts, which may not reflect less receptive contexts. Publication bias may also present a risk of positive bias. Evidence synthesis was impacted by limited robust quantitative studies and a diverse body of qualitative research, which required narrative meta-synthesis. Inherent challenges including variable definitions, inadequate descriptive details and a lack of a core outcomes set, hinder direct implementation and need to be addressed moving forward. Moreover, methodological limitations of meta- synthesis include challenges in transparency between published outcomes and interpreted outputs of evidence synthesis. Here, we applied best practice including a published protocol, PRISMA systematic review, and CASP quality appraisal. We followed the ENTREQ meta-synthesis recommendations to increase transparency of the evidence synthesis. Analysis was underpinned by organisational socialisation theory, with multistep processes applied and expert input gained from across disciplines and sectors. As always, interventions may work in a specific context and local considerations are important in implementation, but the strengths of this study here lie in bringing the accumulated body of evidence from across sectors to inform organisational change.

The barriers to advancing women in healthcare leadership are well entrenched and understood, the case for change is compelling, yet the challenges seem intractable and progress has been slow. In this novel cross sector systematic review and meta-synthesis, we have identified, extracted and synthesised organisational interventions that advance women in leadership, with a focus on learnings relevant to the healthcare sector. Based on largely moderate to high quality literature and on narrative meta-synthesis approaches, here we have highlighted potentially effective organisational approaches. We note the shortcomings of isolated interventions or a “checklist” approach. Rather, evidence suggests that a multilevel organisational approach is vital, starting with committed leadership, understanding of organisational culture and context and co-design of a multifaceted approach with monitoring, evaluation and sustained effort. Within this, a range of interventions can be used, they fall broadly into five categories: organisational processes, awareness and engagement, mentoring and networking, leadership development and support tools. This review has directly informed a large-scale national program funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. With partners across government, health services, professional colleges and international engagement with the UK, we aim to enhance understanding of sector and organisational cultural factors, and adapt, implement and evaluate multilevel approaches. Ultimately, we will co-design an organisational toolkit based on best practice across broad settings for advancing women in healthcare leadership, moving beyond describing the problem and the barriers to delivering effective solutions.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr. Teede reports grants from NHMRC, grants from Medical research Future fund, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Boyle reports grants from NHMRC, grants from Epworth, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Mousa reports grants from Epworth, during the conduct of the study; all other authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Data Sharing statement

All the data used for the study are included in the manuscript and supplementary material.

Funding

Epworth Health, Cabrini and Monash University provided scholarships for MM and AM. HT is funded by an NHMRC / MRFF Practitioner Fellowship, JB by an NHMRC fellowship and HS by a Monash Warwick University Professorship.

Contributors

MM and HT conceived and designed the review. MM and AM collected the data. HT provided critical research input with interpretation and management of results. MM and HT led manuscript preparation. All authors were involved in the overarching protocol, grant funding, interpretation and theoretical underpinning of the data and approved the final version for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Penelope Presta, academic librarian at Monash University, for her invaluable expertise in supporting the search methodology for this review. We also wish to thank our collaborators from Monash University, Centre for Health Research and Implementation, and Epworth Healthcare together with the co-authors for their invaluable input to this review. HT is an NHMRC/MRFF Practitioner Fellow, KR is a Mercator Professorial Fellow, MM is on an Epworth Healthcare scholarship and this work is funded through an NHMRC Partnership Grant (number) and Epworth Foundation Grant.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101084.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.D'Armiento J., Witte S.S., Dutt K. Achieving women's equity in academic medicine: challenging the standards. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):e15–e16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30234-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teede H. Advancing women in medical leadership. Med J Aust. 2019 doi: 10.5694/mja2.50287. (Online 12 August 2019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fine C., Sojo V. Women's value: beyond the business case for diversity and inclusion. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):515–516. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bismark M., Morris J., Thomas L. Reasons and remedies for under-representation of women in medical leadership roles: a qualitative study from Australia. BMJ Open. 2015;5(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(SAGE) SiAGE, Gender equity in STEMM 2016.

- 6.Centre WGEABCE . WGEA gender equity series. Australian Government Workplace Gender Equality Agency; 2019. Gender equity insights 2019: breaking through the glass ceiling. [Google Scholar]

- 7.ACHE DoMS . American College of Healthcare Executives; Chicago IL: 2012. A comparison of the career attainments of men and women healthcare executives. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teede H.J. Advancing women in medical leadership. Med J Aust. 2019;211(9):392–394. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50287. .e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman C., Stilwell, B., Rick, S., Peterson K. Investing in the Power of Nurse Leadership: What Will It Take? 2019, Intrahealth International. Retrieved from https://www.intrahealth.org/sites/ihweb/files/attachment-files/investing-nurse-leadershipreport.pdf

- 10.Taylor K.S., Lambert T.W., Goldacre M.J. Career progression and destinations, comparing men and women in the NHS: postal questionnaire surveys. BMJ (Clin Res Ed.) 2009;338:b1735. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1735. -b35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Betron M., Bourgeault I., Manzoor M. Time for gender-transformative change in the health workforce. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):e25–e26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassells R., Duncan, A. Gender equity insights 2020: delivering the business outcomes. Gender Equity series. 5th ed. The Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre & The Workplace Gender Equality Agency; 2020. Retrieved from https://bcec.edu.au/assets/2020/06/BCEC-WGEA-Gender-Equity-Insights-2020-Delivering-the-Business-Outcomes.pdf

- 13.Ghebreyesus T.A. World Health Organisation; 2019. Female health workers drive global health: we will drive gender-transformative change. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borges N.J., Navarro A.M., Grover A.C. Women physicians: choosing a career in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):105–114. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ab4a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke V., Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol Qual Posit Psychol Edit Kate Hefferon Arabella Ashf. 2017;12(3):297–298. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aldrich M.C., Cust A.E., Raynes-Greenow C. Gender equity in epidemiology: a policy brief. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;35:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassells R., Duncan A. Gender equity insights 2019: breaking through the glass ceiling. BCEC WGEA Gend Equity Ser. 2019:16–68. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coe I.R., Wiley R., Bekker L.G. Organisational best practices towards gender equality in science and medicine. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33188-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnold K.A., Loughlin C. Continuing the conversation: questioning the who, what, and when of leaning in. Acad Manag Perspect. 2019;33(1):94–109. doi: 10.5465/amp.2016.0153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan M.S., Lakha F., Tan M.M.J. More talk than action: gender and ethnic diversity in leading public health universities. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):594–600. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32609-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhatt R., Kickbusch I., Thompson K. Act now: a call to action for gender equality in global health. Lancet. 2017;389(10069):602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moyer C.A., Abedini N.C., Youngblood J. Advancing women leaders in global health: getting to solutions. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84(4):743–752. doi: 10.29024/aogh.2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shannon G., Jansen M., Williams K. Gender equality in science, medicine, and global health: where are we at and why does it matter? Lancet. 2019;393(10171):560–569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter K.P., Clark L., Wick J.A. Women physicians and promotion in academic medicine. New Engl J Med. 2020;383(22):2148–2157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1916935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mousa M.B., A. J., Teede J.H.. Women physicians and promotion in academic medicine [Letter to the editor] New Engl J Med. 2021;384(7):679–680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2035793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boylan J., Dacre J., Gordon H. Addressing women's under-representation in medical leadership. Lancet. 2019;393(10171):e14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Commission E. She figures European union 2016:224.

- 28.The L. Year of reckoning for women in science. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang S.K., Kaplan S. Working toward gender diversity and inclusion in medicine: myths and solutions. Lancet. 2019;393:579–586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Commission E. She figures 2015. 2016

- 31.De Silva J., Prensk-Pomeranz R., Zweig M. Center for Digital Health; 2018. The state of women in healthcare 2018 barriers to career advancement rock health women in healthcare survey standford medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bucknor A., Kamali P., Phillips N. Gender inequality for women in plastic surgery: a systematic scoping review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(6):1561–1577. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirayama M., Fernando S. Organisational barriers to and facilitators for female surgeons' career progression: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2018;111(9):324–334. doi: 10.1177/0141076818790661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laver K.E., Prichard I.J., Cations M. A systematic review of interventions to support the careers of women in academic medicine and other disciplines. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizzirani B., O'Donnell R., Skouteris H. Clinical leadership development in Australian healthcare: a systematic review. Intern Med J. 2020;50(12):1451–1456. doi: 10.1111/imj.14713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rizvi R., Raymer L., Kunik M. Facets of career satisfaction for women physicians in the United States: a systematic review. Women Health. 2012;52(4):403–421. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.674092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bark A.S., Escartin J., van Dick R. Gender and leadership in Spain: A systematic review of some key aspects. Sex Roles A J Res. 2014;70(11–12):522–537. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0375-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Densten I.L., Borrowman L. Does the implicit models of leadership influence the scanning of other-race faces in adults. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(6):1–15.e0179058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campuzano M.V. Force and inertia: a systematic review of women's leadership in male-dominated organizational cultures in the United States. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1534484319861169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tacconelli E. Systematic reviews: cRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):226. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70065-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mousa M., Mullins A.K., Skouteris H., Boyle J., Teede H.J. Organisational best practices for advancing women in leadership: Protocol for a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson K.A., Saldanha I.J., McKoy N.A. Development of a framework to identify research gaps from systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1325–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UK C. Critical appraisal skills programme Summertown Pavilion middleway, Oxford centre for triple value healthcare ltd (3V) portfolio; 2020 [cited 2019. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- 45.Tong A., Flemming K., McInnes E. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12(1):181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandelowski M., Docherty S., Emden C. Qualitative metasynthesis: issues and techniques. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(4):365–371. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199708)20:4<365::AID−NUR9>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao G.T. Organizational socialization: background, basics, and a blueprint for adjustment at work. Oxf Handb Organ Psychol. 2012;1 doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199928309.013.0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banu-Lawrence M., Frawley S., Hoeber L. Women and leadership development in Australian sport organizations. J Sport Manag. 2020;34(6):568–578. doi: 10.1123/jsm.2020-0039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Columbus A.B., Lu P.W., Hill S.S. Factors associated with the professional success of female surgical department chairs: a qualitative study. JAMA Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu T., Shen H., Gao J. Women's career advancement in hotels: the mediating role of organizational commitment. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2020;32(8):2543–2561. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Offermann L.R., Thomas K.R., Lanzo L.A. Achieving leadership and success: a 28-year follow-up of college women leaders. Leadersh Q. 2020;31(4) doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tindell C., Weller R., Kinnison T. Women in veterinary leadership positions: their motivations and enablers. Vet Rec. 2020;186(5):155. doi: 10.1136/vr.105384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Villablanca A.C., Beckett L., Nettiksimmons J. Career flexibility and family-friendly policies: an NIH-funded study to enhance women's careers in biomedical sciences. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20(10):1485–1496. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villablanca A.C., Li Y., Beckett L.A. Evaluating a medical school's climate for women's success: outcomes for faculty recruitment, retention, and promotion. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26(5):530–539. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samuelson H.L., Levine B.R., Barth S.E. Exploring women's leadership labyrinth: effects of hiring and developmental opportunities on gender stratification. Leadersh Q. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gloor J.L., Morf M., Paustian-Underdahl S. Fix the game, not the dame: restoring equity in leadership evaluations. J Bus Ethics. 2018:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10551-018-3861-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D'Agostino M., Levine H. The career progression of women in state government agencies. Gend Manag. 2010;25(1):22–36. doi: 10.1108/17542411011019913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Straub C. A comparative analysis of the use of work-life balance practices in Europe do practices enhance females' career advancement? Women Manag Rev. 2007;22(4):289–304. doi: 10.1108/09649420710754246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villablanca A.C., Beckett L., Nettiksimmons J. Improving knowledge, awareness, and use of flexible career policies through an accelerator intervention at the University of California, Davis, School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):771–777. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828f8974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Green A.C. Women in nonprofit leadership: strategies for work-life balance. Dissertation Abstr Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2016;77(2–A(E)):13–46. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biswas K., Boyle B., Bhardwaj S. Impacts of supportive HR practices and organisational climate on the attitudes of HR managers towards gender diversity – a mediated model approach. Evid Based HRM. 2020 doi: 10.1108/EBHRM-06-2019-0051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adler N.J., Brody L.W., Osland J.S. Advances in global leadership: the women's global leadership forum. Adv Glob Leadersh. 2001;2:351–383. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sexton D.W., Lemak C.H., Wainio J.A. Career inflection points of women who successfully achieved the hospital CEO position. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):367–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Böhmer N., Schinnenburg H. Preventing the leaky pipeline: teaching future female leaders to manage their careers and promote gender equality in organizations. J Int Womens Stud. 2018;19(5):63–81. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ronald B., Mustafa K., Lisa F. Organisational practices supporting women's career advancement and their satisfaction and well-being in Turkey. Women Manag Rev. 2006;21(8):610–624. doi: 10.1108/09649420610712018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burke R.J., Burgess Z., Fallon B. Organizational practices supporting women and their satisfaction and well-being. Women Manag Rev. 2006;21(5):416–425. doi: 10.1108/09649420610676217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barrow J. Leadership sustainability: a study of female airport executives. Dissertation Abstr Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2018;79(12–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pini B. Increasing women's participation in agricultural leadership: strategies for change. J Manag Organ. 2003;9(1):66–79. doi: 10.5172/jmo.2003.9.1.66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pini B., Brown K., Ryan C. Women-only networks as a strategy for change? A case study from local government. Women Manag Rev. 2004;19(6):286–292. doi: 10.1108/09649420410555051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klettner A., Clarke T., Boersma M. Strategic and regulatory approaches to increasing women in leadership: multilevel targets and mandatory quotas as levers for cultural change. J Bus Ethics. 2016;133(3):395–419. doi: 10.1007/s10551-014-2069-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sojo V.E., Wood R.E., Wood S.A. Reporting requirements, targets, and quotas for women in leadership. Leadersh Q. 2016;27(3):519–536. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lafuente E., Vaillant Y. Balance rather than critical mass or tokenism: gender diversity, leadership and performance in financial firms. Int J Manpow. 2019;40(5):894–916. doi: 10.1108/IJM-10-2017-0268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gould J.A., Kulik C.T., Sardeshmukh S.R. Gender diversity from the top: the trickle-down effect in the Australian public sector. Asia Pac J Hum Resour. 2018;56(1):6–30. doi: 10.1111/1744-7941.12158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khuzwayo Z. Separate space: an approach to addressing gender inequality in the workplace. J Int Womens Stud. 2016;17(4):91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watton E., Stables S., Kempster S. How job sharing can lead to more women achieving senior leadership roles in higher education: a UK study. Soc Sci. 2019;8(7) doi: 10.3390/socsci8070209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spencer S.M., Blazek E.S., Orr J.E. Bolstering the female CEO pipeline: equalizing the playing field and igniting women's potential as top-level leaders. Bus Horiz. 2019;62(5):567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2018.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Girod S., Fassiotto M., Grewal D. Reducing implicit gender leadership bias in academic medicine with an educational intervention. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1143–1150. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saad D. Unlocking an unbiased, talent-driven race to the top: increasing access to senior-executive-level positions for women of color. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2018;79(10–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fritz C., van Knippenberg D. Gender and leadership aspiration: the impact of work-life initiatives. Hum Resour Manag. 2018;57(4):855–868. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hua D.W., Mahmood N.H.N., Zakaria W.N.W. The relationship between work-life balance and women leadership performance: the mediation effect of organizational culture. Int J Eng Technol (UAE) 2018;7(4):8–13. doi: 10.14419/ijet.v7i4.9.20608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jones K. Work-life balance: organizational leadership and individual strategies among successful women real estate brokers. Dissertation Abst Int Sec A Humanit Soc Sci. 2018;79(12–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mattingly V.P. Glass kickers: training men as allies to promote women in leadership. Dissertation Abst Int Sect B Sci Eng. 2019;80(5–B(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bruckmüller S., Braun M. One group's advantage or another group's disadvantage? How comparative framing shapes explanations of, and reactions to, workplace gender inequality. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2020;39(4):457–475. doi: 10.1177/0261927X20932631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Leicht C., de Moura G.R., Crisp R.J. Contesting gender stereotypes stimulates generalized fairness in the selection of leaders. Leadersh Q. 2014;25(5):1025–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mölders S., Brosi P., Bekk M. Support for quotas for women in leadership: the influence of gender stereotypes. Hum Resour Manag. 2018;57(4):869–882. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Smith D.A., Arnold W.L., Krupinski E.A. Strategic talent management: implementation and impact of a leadership development program in radiology. J. 2019;16(7):992–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang G., Van Iddekinge C.H., Zhang L. Meta-analytic and primary investigations of the role of followers in ratings of leadership behavior in organizations. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(1):70–106. doi: 10.1037/apl0000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gaetke-Udager K., Knoepp U.S., Maturen K.E. A women in radiology group fosters career development for faculty and trainees. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211(1):W47–W51. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cohen-Jarvie D. The role of social networks in the career advancement of female technology employees in Silicon Valley. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2019;80(5–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guise J.M., Nagel J.D., Regensteiner J.G. Best practices and pearls in interdisciplinary mentoring from building interdisciplinary research careers in women's health directors. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(11):1114–1127. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.O'Neil D.A., Hopkins M.M., Sullivan S.E. Do women's networks help advance women's careers?: differences in perceptions of female workers and top leadership. Career Dev Int. 2011;16(7):733–754. doi: 10.1108/13620431111187317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Madsen S.R., Townsend A., Scribner R.T. Strategies that male allies use to advance women in the workplace. J Mens Stud. 2020;28(3):239–259. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Harris C.A., Leberman S.I. Leadership development for women in New Zealand universities: learning from the New Zealand women in leadership program. Adv Dev Hum Resour. 2012;14(1):28–44. doi: 10.1177/1523422311428747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pike E., White A., Matthews J. The palgrave handbook of feminism and sport, leisure and physical education. 2017. Women and sport leadership: a case study of a development programme; pp. 809–823. Published by Palgrave McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wolff S.J. Investigating the effectiveness of a community leadership program based on the experiences and perceptions of alumni participants. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2019;80(2–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mitchell A.L. Woman-to-woman mentorship: exploring the components of effective mentoring relationships to promote and increase women's representation in top leadership roles. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2018;79(9–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kraft E., Culver D.M., Din C. Exploring a women-only training program for coach developers. Women Sport Phys Act J. 2020;28(2):173–179. doi: 10.1123/wspaj.2019-0047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fassiotto M., Maldonado Y., Hopkins J. A long-term follow-up of a physician leadership program. J Health Org Manag. 2018;32(1):56–68. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-08-2017-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Halcomb E., Jackson D., Daly J. Insights on leadership from early career nurse academics: findings from a mixed methods study. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(2):E155–E163. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Valantine H.A., Grewal D., Ku M.C. The gender gap in academic medicine: comparing results from a multifaceted intervention for stanford faculty to peer and national cohorts. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):904–911. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Culver D.M., Kraft E., Din C. The alberta women in sport leadership project: a social learning intervention for gender equity and leadership development. Women Sport Phys Act J. 2019;27(2 Special Issue):110–117. doi: 10.1123/wspaj.2018-0059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bilimoria D., Singer L.T. Institutions developing excellence in academic leadership (IDEAL): a partnership to advance gender equity, diversity, and inclusion in academic STEM. Equal Divers Incl. 2019;38(3):362–381. doi: 10.1108/EDI-10-2017-0209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tsoh J.Y., Kuo A.K., Barr J.W. Developing faculty leadership from 'within': a 12-year reflection from an internal faculty leadership development program of an academic health sciences center. Med. 2019;24(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2019.1567239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Van Oosten E.B., Buse K., Bilimoria D. The leadership lab for women: advancing and retaining women in STEM through professional development. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2138. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Westring A.F., Speck R.M., Sammel M.D. A culture conducive to women's academic success: development of a measure. Acad Med. 2012;87(11):1622–1631. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826dbfd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hoobler J.M., Lemmon G., Wayne S.J. Women's managerial aspirations: an organizational development perspective. J Manage. 2014;40(3):703–730. doi: 10.1177/0149206311426911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Magrane D., Helitzer D., Morahan P. Systems of career influences: a conceptual model for evaluating the professional development of women in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(12):1244–1251. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pololi L.H., Evans A.T., Civian J.T. A novel measure of "Good" mentoring: testing Its reliability and validity in four academic health centers. J Cont Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(4):263–268. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Caffrey L., Wyatt D., Fudge N. Gender equity programmes in academic medicine: a realist evaluation approach to Athena SWAN processes. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kalpazidou Schmidt E., Ovseiko P.V., Henderson L.R. Understanding the Athena SWAN award scheme for gender equality as a complex social intervention in a complex system: analysis of Silver award action plans in a comparative European perspective. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18(1) doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-0527-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Henderson L.R., Shah S.G.S., Ovseiko P.V. Markers of achievement for assessing and monitoring gender equity in a UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre: a two-factor model. PLoS One. 2020;15(10 October) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bhattacharya S., Bhattacharya S., Mohapatra S. Enablers for advancement of women into leadership position: a study based on IT/ITES sector in India. Int J Hum Cap Inf Technol Prof. 2018;9(4):1–22. doi: 10.4018/IJHCITP.2018100101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bryant L.D., Burkinshaw P., House A.O. Good practice or positive action? Using Q methodology to identify competing views on improving gender equality in academic medicine. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sotiriadou P., de Haan D. Women and leadership: advancing gender equity policies in sport leadership through sport governance. Int J Sport Policy Pol. 2019;11(3):365–383. doi: 10.1080/19406940.2019.1577902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Choi H., Hong S., Lee J.W. Does increasing gender representativeness and diversity improve organizational integrity? Public Pers Manag. 2018;47(1):73–92. doi: 10.1177/0091026017738539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Choo E.K., Kass D., Westergaard M. The Development of best practice recommendations to support the hiring, recruitment, and advancement of women physicians in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(11):1203–1209. doi: 10.1111/acem.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Marin-garcia J.A., Martinez Tomas J. Deconstructing AMO framework: a systematic review. Intang Cap. 2016;12(4):1040–1087. doi: 10.3926/ic.838. https://wwwintangiblecapitalorg/indexphp/ic/article/view/838/574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Burton-Brooks V. Review of advancing women in business: the catalyst guide: best practices from the corporate leaders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2000;24(2):189. doi: 10.1037/h0095095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Abbott A.M. Effects of influence on perceived leadership effectiveness and employee engagement. Dissertation Abst Int Sect B Sci Eng. 2013;73(11–B(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bauman M.D., Howell L.P., Villablanca A.C. The women in medicine and health science program: an innovative initiative to support female faculty at the University of California Davis School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1462–1466. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kilgour M.A., Haynes K., Flynn P.M. Introduction: reducing gender inequality in the workplace through leadership and innovation. Overcoming Chall Gend Equal Workplace Leadersh Innov. 2017:1–6. doi: 10.4324/9781351285322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Carr P.L., Gunn C., Raj A. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: how institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(3):374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lauper A.R. Effects of leadership training and networking opportunities on professional advancement: a quantitative study. Dissertation Abs Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2010;70(11–A):4356. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Morahan P.S., Voytko M.L., Abbuhl S. Ensuring the success of women faculty at AMCs: lessons learned from the national centers of excellence in women's health. Acad Med. 2001;76(1):19–31. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Castillo T.P. A case study approach to the right to health for South Asian indigenous women: interview findings with community-based leaders in the neighboring countries of Nepal and Bangladesh on challenges, best practices, and recommendations. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2016;76(10–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hauser M.C. Leveraging women's leadership talent in healthcare. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.McDonagh K.J., Paris N.M. The leadership labyrinth: leveraging the talents of women to transform health care. Nurs Adm Q. 2013;37(1):6–12. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182751327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.McDonagh K.J., Bobrowski Paula, P. Keogh Hoss, M. Paris, N. M., Schulte M. The leadership gap: ensuring effective healthcare leadership requires inclusion of women at the top. Open J Leadersh. 2014;3:20–29. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Files J.A., Blair J.E., Mayer A.P. Facilitated peer mentorship: a pilot program for academic advancement of female medical faculty. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17(6):1009–1015. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Vinnicombe S., Burke R.J., Blake-Beard S. 2013. Handbook of research on promoting women's careers. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Vinnicombe S., Moore L.L., Anderson D. Edward Elgar Publishing; US; Northampton, MA: 2013. Women's leadership programmes are still important. handbook of research on promoting women's careers; pp. 406–419. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Vinnicombe S., Singh V. Women-only management training: an essential part of women's leadership development. J Change Manag. 2003;3(4):294–306. doi: 10.1080/714023846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bhatia K., Takayesu J.K., Arbelaez C. An innovative educational and mentorship program for emergency medicine women residents to enhance academic development and retention. CJEM, Can. 2015;17(6):685–688. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Piper-Hall S.Y. Creating mentoring success: women making a difference. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2016;76(9–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Pololi L., Knight S. Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.05007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Woolnough H.M., Davidson M.J., Fielden S.L. The experiences of mentors on a career development and mentoring programme for female mental health nurses in the UK National Health Service. Health Serv Manag Res. 2006;19(3):186–196. doi: 10.1258/095148406777888071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ibarra H., Carter N.M., Silva C. Why men still get more promotions than women. Harv Bus Rev. 2010;88(9):80–85. 126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.O'Neil D.A., Hopkins M.M. The impact of gendered organizational systems on women's career advancement. Front Psychol. 2015;6:905. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chang S., Morahan P.S., Magrane D. Retaining faculty in academic medicine: the impact of career development programs for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016;25(7):687–696. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Isaac C., Kaatz A., Lee B. An educational intervention designed to increase women's leadership self-efficacy. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11(3):307–322. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-02-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chuang S. Exploring women-only training program for gender equality and women's continuous professional development in the workplace. High Edu Skills Work Based Learn. 2019;9(3):359–373. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-01-2018-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Butko M.A. Executive MBA programs: impact on female executive career development. Dissertation Abst Int Sect A Humanit Soc Sci. 2017;78(2–A(E)) No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar]

- 143.de la Rey C., Jankelowitz G., Suffla S. Women's leadership programs in South Africa. J. 2003;25(1):49–64. doi: 10.1300/J005v25n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Chang P.L., Chou Y.C., Cheng F.C. Designing career development programs through understanding of nurses' career needs. J Nurses Staff Dev. 2006;22(5):246–253. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Clarke M. Advancing women's careers through leadership development programs. Empl Relat. 2011;33(5):498–515. doi: 10.1108/01425451111153871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Van den Brink M., Stobbe L. The support paradox: overcoming dilemmas in gender equality programs. Scand J Manag. 2014;30(2):163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2013.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.