Abstract

Introduction

Secure messaging is a relatively new addition to health information technology (IT). Several studies have examined the impact of secure messaging on (clinical) outcomes but very few studies have examined the impact on workflow in primary care clinics. In this study we examined the impact of secure messaging on workflow of clinicians, staff and patients.

Methods

We used a multiple case study design with multiple data collections methods (observation, interviews and survey).

Results

Results show that secure messaging has the potential to improve communication and information flow and the organization of work in primary care clinics, partly due to the possibility of asynchronous communication. However, secure messaging can also have a negative effect on communication and increase workload, especially if patients send messages that are not appropriate for the secure messaging medium (for example, messages that are too long, complex, ambiguous, or inappropriate).

Results show that clinicians are ambivalent about secure messaging. Secure messaging can add to their workload, especially if there is high message volume, and currently they are not compensated for these activities. Staff is –especially compared to clinicians- relatively positive about secure messaging and patients are overall very satisfied with secure messaging.

Finally, clinicians, staff and patients think that secure messaging can have a positive effect on quality of care and patient safety.

Conclusion

Secure messaging is a tool that has the potential to improve communication and information flow. However, the potential of secure messaging to improve workflow is dependent on the way it is implemented and used.

Keywords: patient portal, secure messaging, workflow, multiple case study, mixed methods

1. Introduction

Secure messaging is electronic communication about relevant health information between a patient and a health care provider that ensures that only those parties can access the communication (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), 2012). The messages are encrypted and integrity-protected in accordance with standards for encryption and hashing algorithms. In the United States, any electronic communication between patient and provider needs to conform to regulations in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) 1. The first secure messaging systems were implemented more than 10 years ago, mostly as stand-alone systems. Now secure messaging is often a function of a web-based patient portal.

In an early study on secure messaging, Liederman and colleagues (2005) examined the impact of the technology on patient, provider and staff satisfaction, and provider message volume. The authors concluded that uptake of secure messaging was slow; one year after implementation, 6,394 patients out of a patient panel of 135,000 patients (4.7%) were enrolled in secure messaging. These patients sent 6,731 messages in 6 months, fewer than 21% sent 4 or more messages; 34% sent 2-3 messages, and nearly half (45%) sent a single message. Several other studies have found low adoption rates for secure messaging (Boukus, Grossman, & O’Malley, 2010; Goel et al., 2011; Shimada et al., 2013). Goel at al. (2011) examined the reasons for the low uptake of patient portals and secure messaging. Results showed that most respondents (63%) did not attempt enrollment because of lack of information or motivation (did not know about the portal, or did not have instructions; forgot, was too busy). Another 30% did not enroll because of negative attitudes towards the portal (did not think it would be useful, preferred phone over secure messaging).

1.1. Secure messaging and workflow

Relatively few studies have examined the impact of secure messaging on workflow. Workflow is the flow of people, equipment, information and tasks, in different places, at different levels, at different timescales continuously and discontinuously, that are used or required to support the goals of the work domain (Carayon et al., 2012). From a human factors perspective, workflow includes communication, coordination, searching for and interacting with information, problem-solving and planning. Secure messaging can both support workflow, for example by facilitating communication, and hinder workflow, for example by interrupting work processes. One of the main questions about secure messaging is whether it replaces existing workflows such as telephone contacts or clinic visits or it adds to it, by creating a new “channel of communication” and thereby possibly adding to workload. Until recently, most providers dealing with secure messages were not compensated for these activities, but this is starting to change as we are moving toward a global payment system (Song et al., 2011). Liederman et al. (Liederman et al., 2005) and Zhou et al. (2007) examined the impact of secure messaging on primary care utilization. Results showed that access to secure messaging was associated with decreased rates of both office visits and telephone contacts.

Several studies have examined the impact of patient portal on workload. The impact of online messaging on workload is not consistent: several studies report an increase in workload (Byrne, Elliott, & Firek, 2009; Dexter et al., 2016; 2012; Wakefield et al., 2010); some studies report a temporary increase in workload that afterwards plateaus (Grover, Wu, Blanford, Holcomb, & Tidler, 2002; 2005); and other studies report a reduction in workload (Chen, Garrido, Chock, Okawa, & Liang, 2009; Wallwiener, Wallwiener, Kansy, Seeger, & Rajab, 2009; 2010). In most of these studies workload was measured at the clinic level (e.g., volume of secure messages compared to telephone call volume), and not at the individual level. In other words, it is difficult to determine whether providers or staff experienced a change in their workload. Some studies examined the volume of secure messages per provider. Several studies show that volume of secure messages is low (approximately two secure messages per day per provider), and that providers spend about 5-10 minutes a day responding to them (Hobbs et al., 2003; Katz, Moyer, Cox, & Stern, 2003; Liederman et al., 2005). A study by Lin et al. (Lin, Wittevrongel, Moore, Beaty, & Ross, 2005) found that providers received on average one message per day from 250 patients with access to secure messaging.

Several studies examined the effect of the information that patients provide electronically on communication. Many studies focused on the volume of patient-provider communication, but some studies have also examined the quality of communication. In a systematic review, Ye at al. (2010) examined the role of secure messaging in patient-provider communication. The benefits of secure messaging were recognized by both patients and providers, and several studies concluded that secure messaging has great potential to improve patient-provider communication (Katzen, Solan, & Dicker, 2005; Leong, Gingrich, Lewis, Mauger, & George, 2005; Virji et al., 2006). Some of the studies in the review analyzed the content of the secure messages exchanged between patient and provider. Most of the secure messages were about non-acute issues, but a study by Rosen and Kwoh (Rosen & Kwoh, 2007) found that nearly 6% of secure messages were urgent, and 0.002% required a physician’s immediate attention. Several studies examined the characteristics of secure messages and noted that messages were mostly brief, formal and medically relevant (Roter, Larson, Sands, Ford, & Houston, 2008; Sittig, 2003; White, Moyer, Stern, & Katz, 2004). The study by Roter et al. (2008) compared the content of messages sent by patients with those sent by providers to their patients. Provider messages in general were shorter and more direct than patient messages. Patients were generally satisfied with secure messaging (Katzen et al., 2005; Leong et al., 2005).

The literature shows that most studies that examine the impact of health IT on workflow focus on large healthcare organizations (Carayon, Hoonakker, Cartmill, & Hassol, 2015). Small and medium-sized practices are likely to need the most help in analyzing their workflows as they typically do not have access to IT support and quality improvement resources. Therefore, in this study, we examined the impact of secure messaging on workflow in small and midsized practices. Most of the literature has focused on the impact of secure messaging on the work of clinicians. Very few studies have examined the impact on the work of clinic staff. In this study, we examined the impact of secure messaging on workflow of clinicians, staff and patients.

1.2. Research questions

What is the perceived impact of secure messaging on quality of care and patient safety and how satisfied are end-users (clinicians, staff and patients) with secure messaging?

What does the secure messaging workflow look like?

What are workflow facilitators and barriers to secure messaging for clinicians, staff and patients?

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study uses a multiple case study design with mixed methods for data collection (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1984). The five participating clinics (i.e., five cases) are primary care clinics that happen to be located in medium-sized cities. One clinic is located in the Southeastern United States and four clinics are in the Midwestern United States.

2.2. Setting and sample

Clinic and respondent characteristics are summarized in table 1.

Table 1:

Socio-technical characteristics of the 5 participating clinics

| Clinic 1 | Clinic 2 | Clinic 3 | Clinic 4 | Clinic 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of clinic | Internal medicine | Family medicine | Family medicine | Internal medicine | Family medicine |

| Size* | Medium | Small | Small | Medium | Small |

| Location | Midwest | Southeast | Midwest | Midwest | Midwest |

| Years in existence | > 20 years | > 8 years | 1.5 years | > 60 years | 10 years |

| Organizational structure | Final stage of PCMH# | Solo provider supported by clinic manager, MA, receptionist, and billing specialist. | Advanced stage of PCMH implementation | Early stage of PCMH | Early stage of PCMH |

| Clinic staff: | |||||

| Clinic manager | 1 (staff) |

1 (staff) |

1 (RN) |

2 (staff and RN) |

1 (RN) |

| Physicians | 7 (6 FTE) |

1 | 3 | 7 (6 FTE) |

8 (3 FTE) |

| PAs and NPs | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| RNs | 6 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 6 |

| LPNs | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| MAs | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Schedulers | 7 (shared) | 1 | 3 | 8 (shared) | 3 |

| Other staff | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Patients | ~14,000 | ~4,500 | ~2,500 | ~7,200 | ~5,000 |

| EHR | Epic, implemented in 2001 | Bizmatics Prognosis, implemented in 2005 | Epic, implemented in 2012 | Epic, Implemented in 2012 | Epic, implemented in 2001 |

| Patient portal | Epic MyChart implemented in 2006 | Prognosis patient portal, implemented in 2005 | Epic MyChart implemented in 2012 | Epic MyChart implemented in 2012 | Epic MyChart implemented in 2012 |

| Secure messages received per provider per day | 10-12 | 30-40 (including secure messages and email) | 4-6 | 4-6 | 0-1 |

| Clinicians^ who communicate with % of patients using secure messaging | ~23% | ~18% | ~26% | ~12% | ~10% |

| Staff^ who communicate with % of patients using secure messaging | ~28% | ~18% | ~18% | ~0% | ~0% |

A small clinic is defined as a clinic with fewer than 5 full-time equivalent (FTE) physicians; a medium-sized clinic is defined as a clinic with in between 5 and 10 FTE physicians.

Patient-centered medical home (PCMH): working in care teams of providers, triage RNs and LPNs or MAs. Schedulers work either in-house or in a scheduling pod.

Clinicians: Physicians, advanced practitioners (physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs)), nurses (registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses (LPNs)); staff: schedulers, receptionists, medical assistants (MAs) and patient care associates (PCAs).

2.3. Data collection procedures

2.3.1. Pre-visit questionnaire

Prior to the data collection visit, we held a conference call with the clinic manager and/or physician leader to explain the research study and organize logistics for the site visit. We also used a pre-visit questionnaire to collect data on clinic characteristics (e.g., year when clinic was founded) and the implementation of health IT applications (see Table 1).

2.3.2. Combined observations and interviews

During the data collection site visit, often observations were conducted concurrently with interviews of clinicians and staff. We conducted 39 observations/interviews with clinicians; 13 observations/interviews with clinic staff, and 27 interviews with patients. In total, the observations and interviews with clinicians, staff and patients in the 5 clinics lasted nearly 60 hours (see Table 2).

Table 2:

Data collection overview

| Clinic 1 | Clinic 2 | Clinic 3 | Clinic 4 | Clinic 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations and interviews with clinicians (n and duration in hours and minutes) | N=12 17:29 |

N=1 1:50 |

N=5 4:15 |

N=13 10:42 |

N=8 6:12 |

N=39 40:28 |

| Observations and interviews with staff (n and duration in hours and minutes) | N=7 6:42 |

N=4 4:41 |

N=2 1:43 |

NA | NA | N=13 13:06 |

| Interviews with patients (n and duration in hours and minutes) | N=6 1:34 |

N=5 1:16 |

N=6 1:10 |

N=7 1:44 |

N=3 0:32 |

N=27 6:16 |

| Total observations and interviews with clinicians, staff and patients (n and duration in hours and minutes) | N=25 25:49 |

N=10 7:47 |

N=13 7:08 |

N=20 12:26 |

N=11 6:44 |

N=79 59:50 |

| Total surveys distributed (n) | N=42 | N=55 | N=11 | N=28 | N=17 | N=103 |

| Total surveys returned (n) | N=37 | N=5 | N=7 | N=21 | N=15 | N=85 |

| Response rate to survey (%) | 88.1% | 100.0% | 63.5% | 75.0% | 88.2% | 82.5% |

NA: Not applicable: staff is not involved in secure messaging and was therefore not interviewed.

2.3.3. Survey

A questionnaire was developed to measure end-user satisfaction with secure messaging. On the second day of the clinic visit, clinic employees received an invitation to participate in the survey, followed by three reminders, respectively two, five and seven days after the initial invitation. This procedure resulted in an overall response rate of 83% (see Table 2). Staff in clinics 4 and 5 were not involved in secure messaging and, therefore, were not interviewed nor surveyed. Forty-three clinicians and 15 staff members filled out the questions about secure messaging in the survey.

Survey respondents varied in age from younger than 30 years (29%) to 55 years or older (25%). Most respondents were female (81%). On average, respondents had more than 15 years of computer experience, and most users (74%) considered themselves average (use word processor, spreadsheet, e-mail, the Internet, etc.) or advanced (can install software, set up configurations, etc.) users (24%). There are no statistically significant differences in personal and job characteristics between respondents in the 5 clinics.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) also approved all data collection activities.

2.4. Data collection instruments

All data collection instruments can be found on: http://cqpi.wisc.edu/health-it-practice-redesign.htm.

2.4.1. Pre-visit questionnaire

The pre-visit questionnaire consists of 16 questions about characteristics of the clinic (e.g., type of clinic, staff, and number of patients), health IT in use at the clinic (e.g., number of patients actively using secure messaging), implementation of health, and satisfaction with different health IT applications (see Table 1).

2.4.2. Observation forms

Observations were focused on how secure messages are received from patients and integrated into other existing health information systems (e.g., EHR); and when and how messaging is used by physicians, other clinicians, and office staff. Researchers observed physicians, other clinicians and office staff as they integrated message content and worked with secure messaging. Observations were focused on processes, bottlenecks, facilitators and barriers, and workarounds. During observations, researchers asked follow-up questions of those being observed to ensure that the workflows were correctly understood, clarify how individuals share information and responsibilities, and understand variations from one individual to another. Detailed notes were recorded on the observation data collection sheet and typed up as soon as possible upon completion of the observation.

2.4.3. Interviews

We conducted 5 types of interviews: interviews with clinic managers, physician leaders, clinician, staff and patients. The interview guides for clinicians and staff were identical.

2.4.3.1. Interview with clinic manager

A guide was developed for the interview with the clinic manager, including 14 questions about the history and current status of the clinic; patients in the clinic; how the clinic is organized; daily workflow in the clinic, use of health IT in the clinic and the impact of these applications on the clinic; usefulness and usability of the applications; facilitators and barriers to health IT implementation; and whether the implementation of health IT had provided opportunities for redesign of clinic workflows.

2.4.3.2. Interview with physician leader

The interview guide for the physician leader included questions about the history and current status of health IT in the clinic; health IT support; future health IT plans; training for health IT; the impact of the applications on the clinic; security and privacy of health IT; the impact of the applications on patient satisfaction; and facilitators and barriers to health IT implementation.

2.4.3.3. Interview with clinicians and staff

Interviews with clinicians and staff included questions about health information technologies that the interviewee was familiar with. During the interview, clinicians and staff were asked how each application affected their work, work environment, and workflow; the impact on communication; usability and usefulness of secure messaging; the impact of secure messaging on quality of care and on patient satisfaction; and facilitators and barriers to the use of secure messaging, including privacy and security issues. We also asked interviewees how satisfied they were with secure messaging, on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied).

2.4.3.4. Interview with patients

Interviews with patients included questions about how often patients use secure messaging; for what reasons they contact the clinic; the workflow of sending and receiving a secure message; the response time; usefulness of and overall satisfaction with secure messaging on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied).

2.4.4. Survey

A questionnaire was developed and administered as a Web-based survey to measure user satisfaction with secure messaging. The surveys were used to collect data regarding attitudes about and perceptions of the secure messaging workflow staff engage in. In this paper we focus on questions about secure messaging (Do you use secure messaging? With what percent of patients do you communicate by secure messaging?); and 12 questions about user satisfaction with secure messaging for clinicians and 8 questions for staff (see Table 8). The questions on user satisfaction were adapted from the POESUS (Hoonakker, Carayon, & Walker, 2010; Lee, Teich, Spurr, & Bates, 1996).

Table 8.

Comparison of workflow facilitators and barriers of secure messaging for clinicians, staff and patients, sorted by largest facilitator for clinicians

| Clinicians (N=38) |

Staff (n=12) |

Patients (N=27) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | F | B | F | B | F | B |

| Communication/ information flow | 76% | 84% | 58% | 42% | 52% | 0% |

| Organization of work | 62% | 46% | 58% | 33% | 81% | 7% |

| Amount of work | 46% | 49% | 50% | 42% | 30% | 11% |

| Usability | 24% | 51% | 33% | 33% | 41% | 26% |

| Task complexity /simplicity | 8% | 22% | 17% | 17% | 19% | 4% |

| Workaround | 8% | NA | 8% | NA | 4% | NA |

| Ambiguity/ clarity | 8% | 43% | 25% | 42% | 15% | 4% |

| Inappropriate use | NA | 62% | NA | 17% | NA | 0% |

| Quality of care/ patient safety | 51% | 24% | 33% | 0% | 11% | 0% |

| Patient satisfaction | 51% | 19% | 17% | 8% | NA | NA |

| Satisfaction with technology | 43% | 19% | 42% | 25% | 52% | 4% |

| Mean # of instances when dimension is mentioned, per interview (SD) | 3.7 (2.06) | 4.1 (2.04) | 3.3 (2.21) | 2.4 (2.07) | 3.2 (1.50) | 0.6 (0.78) |

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Observations/Interviews

The observation notes were used to create process maps of the secure messaging workflow in the clinics (see Figure 1 for an example). Interview and concurrent observation-interview data were uploaded into Dedoose©, a qualitative data analysis software. The research team read and discussed three of the clinician and staff interviews from the first clinic. We developed descriptors to attach to each interview or concurrent interview and observation (e.g., clinic, job title) and a node structure in an iterative process. We developed a preliminary list of nodes by selecting from nodes identified in previous health IT research and adding nodes that were needed to answer our research questions. As data analysis progressed, the initial node structure was refined several times. In our analyses, we refer to these nodes as dimensions. Table 3 contains the definition of each dimension for the analysis of facilitators and barriers to workflow. We use the term dimension because the same dimension can be perceived either as a barrier or a facilitator to the workflow associated with a health IT application. Further, we distinguished between (1) workflow facilitators and barriers, and (2) facilitators and barriers to possible outcomes (i.e., satisfaction with technology, patient satisfaction, and perceived quality of care and patient safety).

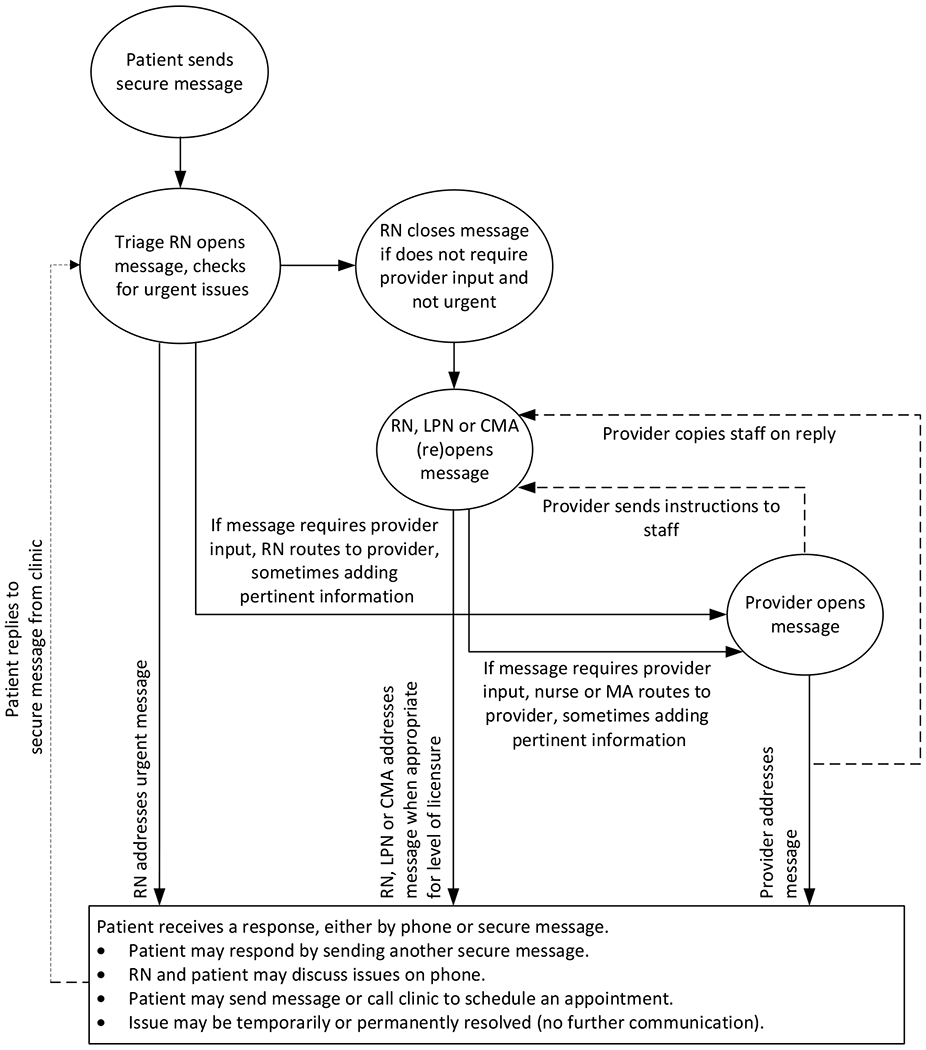

Figure 1.

Secure messaging workflow in clinic #1

Table 3.

Definitions of dimensions used in coding facilitators and barriers to workflow [or Appendix]

| Dimensions | Definition as a barrier | Definition as a facilitator |

|---|---|---|

| Amount of work | Secure messaging has increased workload and issues related to workload, such as an increase in amount of work, more time needed to finish tasks, and duplication of tasks. | Secure messaging has decreased workload and issues related to workload, such as a decrease in amount of work, and less time needed to finish tasks. |

| Task complexity-simplicity | Secure messaging has caused processes to become more complex. This includes having more actors involved in a task and having to complete more steps per task. | Secure messaging has caused processes to become less complex, including having fewer actors involved in a task and having to complete fewer steps per task. |

| Inappropriate use | Clinicians, staff or patients use secure messaging in a way that the clinic did not intend it to be used. | Not applicable |

| Workaround | Not applicable | Clinicians, staff or patients develop workarounds to circumvent barriers related to use of secure messaging in order to get their work done. |

| Usability* | Problems related to the design of secure messaging affect effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction of users. | Characteristics of the design of secure messaging support effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction of users. |

| Communication and information flow | Secure messaging has changed communication or information flow for the worse. Communication has become more difficult or information flow has changed for the worse. Includes communication with patients, clinicians or staff; frequency of communication; and quality of communication. | Secure messaging has improved communication or information flow, including communication with clinicians, patients or staff; frequency of communication; and quality of communication. |

| Ambiguity-clarity | Secure messaging has caused processes and tasks to become more ambiguous, including who will perform specific tasks and when but excluding communication. | Secure messaging has caused processes and tasks to become clearer and less ambiguous, including who will perform specific tasks and when but excluding communication. |

| Organization of work | Secure messaging has negatively impacted work processes and tasks, including the sequence of tasks, who does tasks and when, priority of tasks, and dependency of tasks on other tasks. | Secure messaging has positively impacted work processes and tasks, including the sequence of tasks, who does tasks and when, priority of tasks or dependency of tasks on other tasks. |

| Satisfaction with IT application | Secure messaging has had a negative impact on the user’s satisfaction with health IT used in the clinic.’ | Secure messaging has positively affected the user’s satisfaction with health IT used in the clinic.’ |

| Patient satisfaction (Clinicians and staff only) | Secure messaging has made patients less satisfied with the clinic or the care they receive. | Secure messaging has made patients more satisfied with the clinic or the care they receive. |

| Quality of care and patient safety | Secure messaging has negatively affected the quality of care and patient safety. | Secure messaging has positively affected the quality of care and patient safety. |

Our definition of usability barrier and facilitator is based on the ISO 9241 definition (“The extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use.”).

Note that we interviewed physician leaders, clinic managers, clinicians, staff, and patients. The physician leaders were coded as clinicians; the clinic managers were either coded as clinicians (if they were nurses) or as staff (if they did not have a clinical background). All interviews were coded using the same dimensions.

After we coded all the interviews, we used Dedoose© to create matrices of the facilitators and barriers for clinicians, staff and patients. We analyzed the data by assessing whether facilitators and barriers related to each dimension were identified in each interview and/or observation. The goal of the qualitative data analysis was to categorize and compare facilitators and barriers. Therefore, we report the percentage of interviews in which facilitators and barriers associated with each dimension were identified. Our analysis assesses whether each data source contains information on any facilitators (or barriers) related to each dimension, not the number of facilitators (or barriers) described.

We used heat maps to summarize data on facilitators and barriers to secure messaging. If a barrier or a facilitator was mentioned in 33% or fewer of the interviews, it was considered a minor barrier or facilitator; if a barrier or facilitator was mentioned in more than 33% and less or equal to 67% of all interviews, it was considered moderate; and if a barrier or facilitator was mentioned in more than 67% of all interviews, it was considered a major barrier or facilitator. We analyzed interviews with clinicians, staff and patients separately.

2.5.2. Survey data analysis

Descriptive statistics were created for the individual clinics and the whole dataset. Chi-square-tests were used to determine differences between the clinics. Only 43 clinicians and 15 staff used secure messaging and filled out the questions about secure messaging in the survey. Because of this small number, we only compare clinicians and staff and do not compare the results across clinics.

3. Results

3.1. Secure messaging workflow

Figure 1 summarizes the secure messaging workflow for clinic 1. There were differences between the secure messaging workflow in the different clinics depending on the way the clinics are organized (see Table 2). For example, in clinics with a team structure, both clinicians and staff are involved in the secure messaging workflow. Secure messages arrive in the inbox of the team. The triage nurse checks messages for urgency and decides whether she needs to deal with the message, whether the messages need to be routed to the physician, or whether the message can stay in the inbox and can be handled by clinic staff. In this way, the secure messages are “pushed” down to the lowest level, and greatly reduce physician input. Other clinics either do not have a team structure, which means that the bulk of the messages end up in the physician’s inbox (e.g. clinic #2), or they have a team structure but are in early stages of implementation, which means that the secure messaging workload is shared by the providers and nurses and that staff is not involved in the process (e.g. clinics 4 and 5).

3.2. Facilitators and barriers to secure messaging workflow

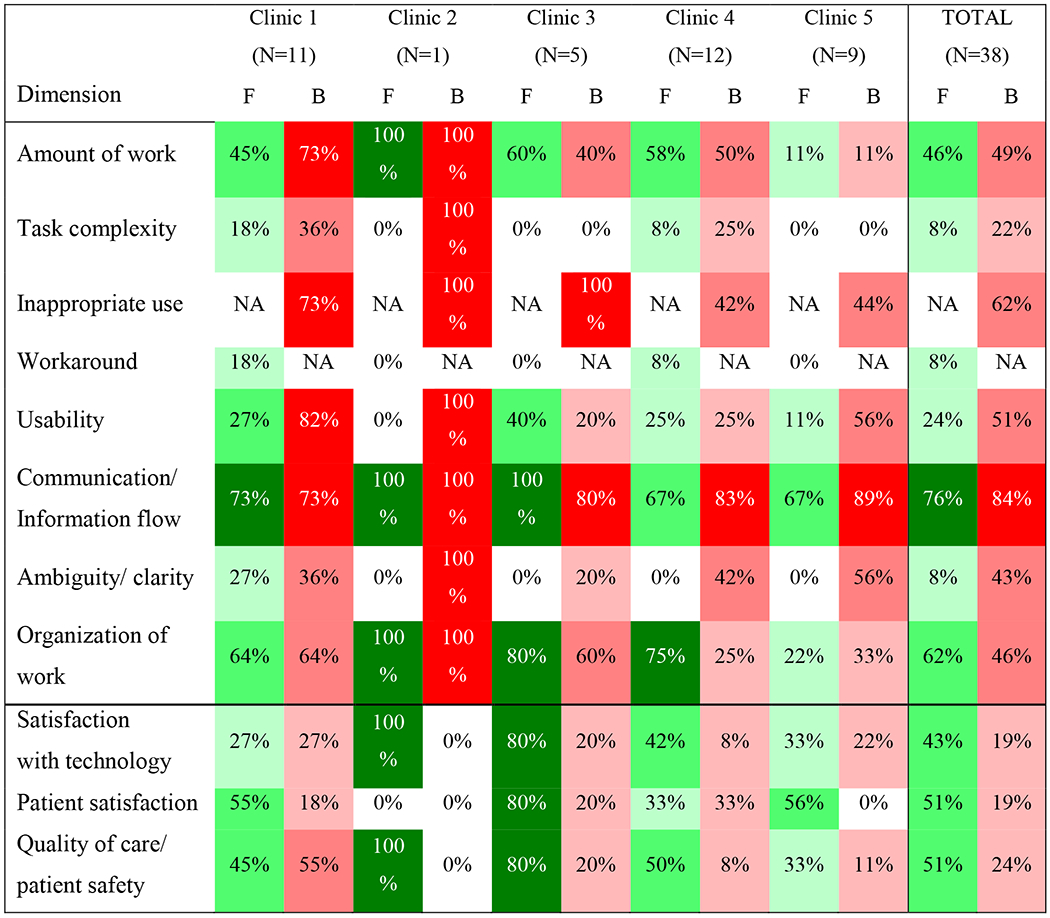

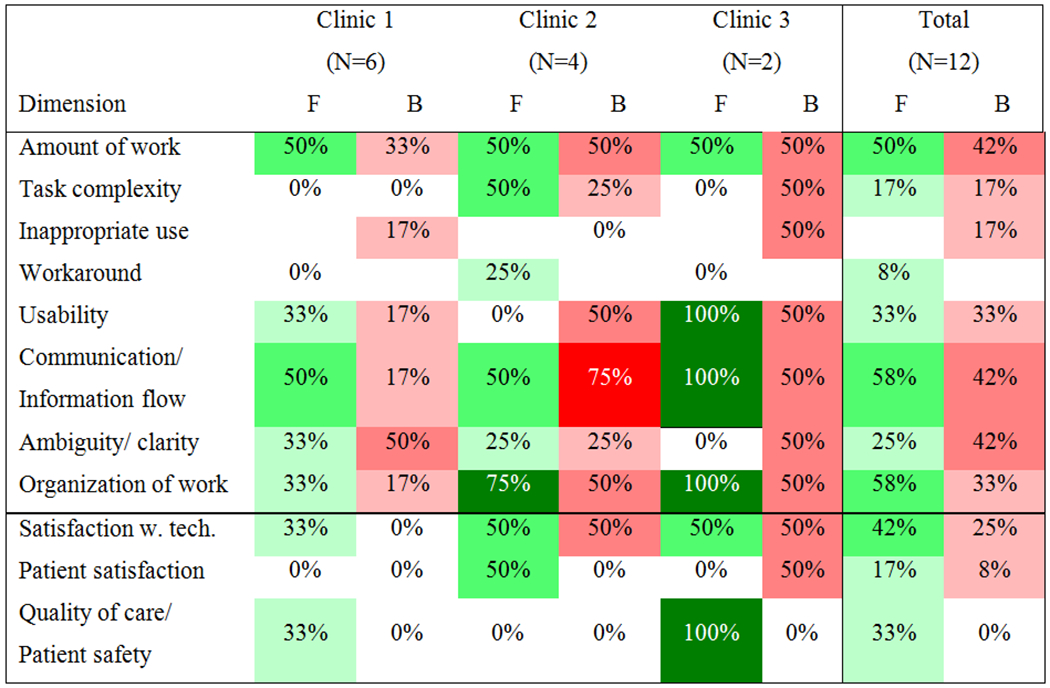

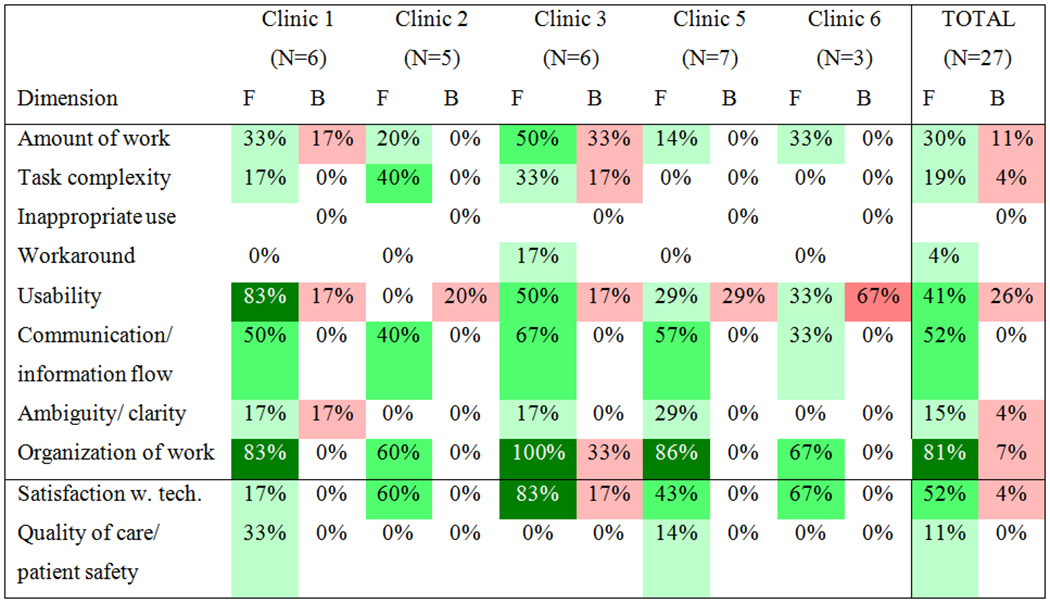

Tables 4, 5 and 6 summarize workflow facilitators and barriers for clinicians, staff and patients. Facilitators and barriers have three levels: low (light shading, mentioned in 0–33% of all interviews), medium (intermediate shading, mentioned in 34–67% of all interviews) and high (pronounced, mentioned in 67% or more of all interviews).

Table 4:

Facilitators and barriers to secure messaging workflow for clinicians (n=38)

|

Table 5:

Facilitators and barriers to secure messaging workflow for staff (n=12)

|

Table 6:

Facilitators and barriers to secure messaging workflow for patients

|

3.2.1. Facilitators and barriers to clinician secure messaging workflow

Results in Table 4 show that, overall, the most often mentioned barrier (84%) in secure messaging workflow is communication and information flow. The second most often mentioned barrier is inappropriate use (62%) and the third most often mentioned barrier is (lack of) usability (51%). Results also show the variation between the clinics: amount of work and inappropriate use are more often mentioned in clinics 1, 2 and 3, as compared to clinics 4 and 5. Communication and information flow is also most often mentioned as a facilitator to secure messaging (76%), followed by organization of work (62%) and amount of work (46%).

3.2.1.1. Secure messaging workflow barriers for clinicians

Communication and information flow is perceived as one of the most important barriers to secure messaging by clinicians. Both providers and nurses mentioned that secure messages lack the contextual information that face-to-face communication or even phone calls contain, which can make the correct interpretation of messages more difficult.

I think that there is something to verbal communication versus written or electronic. You can hear things in the patient’s voice. Or you can tell if they were to write about symptoms they were having, it may be different when they type it versus when you talk to them.… [Y]ou might be able to hear that they are short of breath, those types of things. So I think you could easily be missing information through electronic messaging. (Clinic 4, RN3)

Inappropriate use is mentioned in 62% of interviews as a barrier. In most clinics, the secure message functionality is intended for the following purposes: to send a message about a non-urgent, medical issue, laboratory tests, medications or follow-up. The secure messaging functionality is in most clinics not intended for billing questions, medication refills, scheduling appointments, or for asking questions about family members, but patients often use it for that purpose. Further, some patients use secure messaging to avoid co-payments required for a clinic visit. Second, the content of the message is important. When asking a question, patients should provide concise information, but sometimes patients provide too little or too much information. (Secure messages can sometimes contain more than 2 pages of information.) Some patients write too many secure messages in a short period of time, making it difficult for the nurse to address the patient’s concerns: “Patients … overuse [secure messaging] to the point where [they]’re actually impeding my ability to help [them] because [they]’re messaging me so much” (Clinic 4, RN 1). Finally, some patients ask many questions about a complicated medical condition, which would be more appropriately addressed in an office visit.

Several usability barriers were described by users of secure messaging. One arises when, instead of creating a new secure message, a patient responds to a message that he received from the clinic at an earlier time. Doing this requires the clinician opening the message to review all of the content from the previous conversation as well as the new message, which can cause confusion. For example, several nurses and providers described how the organization of a secure message and its replies is confusing.

INTERVIEWER: So you’re going back and forth, up and down?

RESPONDENT: Yes, … and like I said, it’s hard. I, sometimes I go back, and I have to think, okay, which? This one I already read, but where is the next one. And see, my … response gets mixed in down here again, her first note that she sent to me is here. Her next one is here, but here’s my note, and here’s her first one again.…. But my answers that I get sent back also come in down here. See, here’s my notes that I typed above, but it also comes back interspersed in here, and it’s duplicated, because there’s her note again, there’s my note again…. So in answering her message, you have to figure out that stream of messages and where you are in that stream of messages. (Clinic 1, Physician 2)

3.2.1.2. Secure messaging workflow facilitators for clinicians

Communication and information flow can be perceived as a facilitator. One of the main advantages of secure messaging is that it allows for asynchronous communication and that in most cases clinicians can respond to a secure message at a convenient time. Further, according to several clinicians, secure messaging can lead to patient engagement and empowerment. These clinicians stated that secure messaging improved workflow by opening a new line of communication for patients to reach the clinic.

It allows the patients to feel like they can interact with their provider at any given time. The [patient] who e-mails me a couple times a week, it’s often [at] 2:00 in the morning.… I think that’s a very reassuring thing. She knows I’m seeing it. She’s communicating to me. (Clinic 5, NP)

Clinicians also mentioned that it is easier for patients to send a message than to call the clinic and “play phone tag”. Patients are therefore more likely to share information that is useful for clinicians and to be engaged in their care. Finally, several clinicians stated that some patients are able to communicate questions in a message that they are embarrassed to talk about with reception staff or ask in person.

Secure messaging can also help with the organization of work. One important facilitator for providers is that nursing staff in most clinics try to address as many messages as possible without involving the provider. Providers also have the flexibility to answer messages directly or delegate that task to nursing staff. Another facilitator mentioned by clinicians is that patients “transcribe” their own concerns by typing in the message themselves, saving staff time. The asynchronous nature of communication through secure messaging was a facilitator mentioned by several providers, because they can address messages as they have time. Nurses also feel this is a facilitator, because the asynchronous communication allows them to research the issues raised in a secure message without feeling time pressure.

[I]t gives us more of a chance -- without [the patient] sitting on the other end with that dead air -- to pull up more records or to get their paper chart…. That patient sitting on the phone, they dont’ want to call back…. [T]hey want that answer more immediate[ly]. Whereas, [using] MyChart I can do all that stuff without them knowing that I’m doing it, because they’re not just waiting.… [I can] talk to a provider … without interrupting anybody’s workflow. (Clinic 4, RN 1)

Secure messaging can reduce the amount of work. Providers mentioned that secure messaging improved the clinic’s overall efficiency, not because fewer messages are received but because some messages have been “shifted … to quicker, efficient messaging from the callback and the delay” (Clinic 1, Physician 1). For nurses, who often have to play phone tag with patients, secure messaging can save time and effort.

[Secure messaging is] a nice, easy way for me to let [a patient] know something, and I won’t have to play phone tag with [them]… [T]hat’s kind of a relief for a triage nurse, because phone tag is frustrating for both of us and time consuming. (Clinic 4, RN 4)

3.2.1.3. Impact of secure messaging on satisfaction, quality of care and patient safety according to clinicians

Overall, a majority of clinicians think that secure messaging has a positive impact on patient satisfaction, quality of care and patient safety. Clinicians stated that the ease of communication encourages patients to more often share information useful for their care. Also, some patients review their medical records on a patient portal and send the clinic messages to correct errors.

[Patients] review their problem list, their immunizations, their medication list, and will say, oh, I’ve had this vaccine. Or I had one last week of a guy who was flagging as due for a diabetic foot exam. But he wrote and said, I had a diabetic foot exam with [my PCP] at my appointment in April. So I went into the office visit from April, and sure enough, she did the diabetic foot exam. So then in [the EHR] I could go into the health maintenance and put that as completed. … Or this isn’t the dose of the medication I take anymore, my cardiologist changed it. (Clinic 4 RN)

3.2.2. Facilitators and barriers to staff secure messaging workflow

Table 5 summarizes the facilitators and barriers to staff secure messaging workflow. In clinics 4 and 5, staff were not involved in secure messaging and, therefore, were not interviewed.

Results show that, compared to clinicians, staff perceive fewer barriers and more facilitators to secure messaging. The main barriers are: amount of work, communication and information, and ambiguity/clarity, all mentioned in 42% of interviews. The main facilitators are: organization of work (58%), communication and information (58%) and amount of work (50%).

3.2.2.1. Secure messaging workflow barriers for clinic staff

Secure messages sent by patients can sometimes increase the workload of staff, especially if the messages are inappropriate. Some patients include a lot of non-clinical information in secure messages, adding to workload. “I don’t like messages where the patient is rambling [about non-clinical information, then asks] can I have a refill?” (Clinic 3 MA).

Many of the communication barriers identified by staff were similar to those reported by clinicians. Several staff stated that communication can be less clear and more confusing and that patients sometimes report too much information in a single secure message. Also, staff mentioned that a patient’s tone of voice gives useful information that is lost when secure messaging is used. Another communication barrier is that some patients do not read message replies sent by the clinic, sometimes calling the clinic to check about the issue instead. A related barrier is that some patients expect an immediate reply to each secure message and call the clinic if they do not receive one (channel switching).

There can be ambiguity with regard to the content of a message (what the patient means) and with regard to the status of a message. Especially in clinics with a team structure, it is not always clear who is working on a message. Sometimes this requires searching through a long string of messages or conducting other research in the patient’s medical record.

3.2.2.2. Secure messaging workflow facilitators for clinic staff

Many staff described facilitators related to the organization of work. One was that responding to secure messages is easier than calling patients, particularly because staff cannot include certain types of information in a phone message.

Sometimes the patient calls, and then they go back to work, and they don’t answer their phone call even though they just called you, or they’re busy…. I feel like [with] the phone calls there’s a lot of phone tag going on. And with the MyChart… it’s HIPAA protected, and I can say what I need to say without worrying about saying something that shouldn’t be said [in a voicemail message]. (Clinic 3 MA)

Staff reported that the use of secure messaging helps patients to manage chronic conditions without requiring the patient to come in for an office visit. In one clinic, diabetic patients are asked to give updates – via secure messaging or phone – on how their medications are working, particularly after medication changes. Another facilitator was that secure messages are routed to the clinic staff member who can best resolve the issue, saving the patient from having to wait on hold during a phone call to the clinic while some other staff member attempts to resolve it.

Secure messaging can facilitate the communication and information flow of clinic staff, and often in a similar way as described by clinicians. For example, staff described how secure messaging provides another route of communication between the clinic and patients. Staff also described how family members may use secure messaging to stay informed about the care of their loved ones.

Several staff members reported that secure messaging reduces their workload compared to addressing the same issues with phone calls because “sending out a 30-second e-mail is much faster than talking to someone” (Clinic 2 manager). Other staff suggested that secure messaging also reduces office visits with nurses.

3.2.2.3. Impact of secure messaging on satisfaction, quality of care and patient safety according to staff

Compared to physicians, staff is less positive about the impact of secure messaging on quality of care, patient safety and patient satisfaction. Several staff mentioned that secure messaging can save patients a trip to the clinic.

I just think they feel like they have a little more control over what they can access. And they can’t, you know, I’m not saying they should be MyCharting [secure messaging] for every little thing, but I think that if they could and get a quicker response, it might save them a trip in. Clinic 1, MA

3.2.3. Facilitators and barriers to patient secure messaging workflow

Compared to clinicians and to a lesser extent staff, secure messaging improves workflow for patients. The main facilitators to secure messaging are: organization of work (81%), communication and information flow (52%), and usability (41%). Only a few patients mention barriers to secure messaging. Usability (25%), the amount of work (11%) and the organization of work (7%) are perceived as barriers by a few patients.

3.2.3.1. Secure messaging workflow barriers for patients

Only a few patients mentioned barriers to secure messaging. A number of patients experienced usability problems using secure messaging. For example, a patient at Clinic 4 said that he had not received an email letting him know that he had received a secure message. One patient had trouble deleting the confirmation messages after cancelling an appointment at Clinic 3. She ended up having 25 messages cluttering her inbox. One patient at Clinic 5 was frustrated when he was inadvertently sending duplicates of the same message.

3.2.3.2. Secure messaging workflow facilitators for patients

Many patients said that secure messaging is helpful because it makes the organization of work easier. For example, they do not have to call the clinic and spend time on hold.

[You] have to … wait endlessly for the phone to answer. Are you an [clinic] patient, or are you not? Then it goes, you can now wait. You know, they’re busy. So then you wait and wait and wait. If you [write a secure message], the nurse will call you at their convenience and say, hey, how are you doing? (Clinic 5 Patient).

Several patients explained how using secure messaging fits better into their daily routines or their work day, compared to phone calls. Many patients mentioned that secure messaging allows them to easily communicate with the clinic as often as they wish. One patient used secure messaging frequently when she was pregnant. She had “a lot of questions that … I don’t need an answer right now, but it’s just nice to know that [the clinic] can respond back when they get a chance” (Clinic 3, Patient 2). Another patient who had been frequently hospitalized said that it helped her to handle the changes in medications related to being admitted and discharged from the hospital. Some patients stated that communication by secure messaging helps them to share information with the clinic because they are able to take the time to write the message carefully at home, ensuring that all important issues are included. In an office visit, they are more likely to forget some of their questions. Also, many patients stated that secure messaging was useful for questions that were forgotten during an office visit.

I do forget to say things when I’m here. And I like the fact that I can go back, or when I’m driving home, or back to work, I realize I had forgotten that. So I just jump on MyChart and send that message (Clinic 3 Patient).

Finally, patients also liked the fact that the information they received through secure messaging was written and could be reviewed later.

Many patients described the usability of the secure messaging system as a facilitator. Most stated that the system is easy to use because the patient portal used by their clinic is self-explanatory. “The links are easy, and they’re listed. So if I want to send a message to my doctor, I just hit the link and the box pops up, and I send a message that I want” (Clinic 3 Patient). Some patients use a mobile app on their smart phones, which allows them to send message at any time and from any location. “I might be at the store, and I want to do a MyChart message. I can just [use] my phone right there” (Clinic 5 Patient).

3.2.3.3. Impact of secure messaging on satisfaction with technology, quality of care and patient safety according to patients

Most patients are very satisfied with the technology. A few patients mentioned that secure messaging improves their ability to manage their medical condition and communicate quickly with the clinic.

I feel very comfortable with our, my patient/physician relationship and the nurses here, and I think the MyChart enhances that. I think it saves me time. I don’t have to make a phone call and sometimes trade phone calls, because if I’d be between meetings or something, you know, that happens sometimes. So I’m getting better at looking at it more frequently. Clinic 5, patient

3.3. End-user satisfaction with secure messaging

Forty-three clinicians and 15 staff members were involved in the secure messaging process in their clinic and responded to survey questions on satisfaction with secure messaging. Results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7:

End-user satisfaction with secure messaging, clinicians (n=43) versus staff (n=15), sorted by percent agreement (Clinicians)

| Clinicians (n=43) | Staff (n=15) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disagree | Neither | Agree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | |

| Secure messaging has a positive impact on patient satisfaction. | 2% | 26% | 72% | 7% | 13% | 80% |

| Secure messaging has a positive effect on patient-clinician communication. | 9% | 30% | 61% | NA | NA | NA |

| The information I receive from secure messaging makes an impact on my decision making. | 16% | 23% | 61% | NA | NA | NA |

| Secure messaging makes communication with patients more efficient * | 12% | 33% | 56% | 0% | 13% | 87% |

| Overall, I am satisfied with secure messaging | 14% | 33% | 52% | 7% | 7% | 87% |

| Secure messaging improves the quality of patient care. | 21% | 37% | 42% | 7% | 29% | 64% |

| Secure messaging has a negative effect on my workflow | 40% | 28% | 33% | 60% | 27% | 13% |

| Overall, secure messaging saves me time *** | 51% | 28% | 21% | 7% | 20% | 73% |

| Secure messaging reduces patient care errors. | 23% | 63% | 14% | NA | NA | NA |

| The information I get from secure messaging makes my work easier *** | 35% | 51% | 14% | 7% | 20% | 73% |

| Secure messaging reduces my workload ** | 63% | 30% | 7% | 20% | 47% | 33% |

| Secure messaging has a negative impact on patient care. | 61% | 37% | 2% | NA | NA | NA |

NA: not applicable (question was not asked to staff);

differences between clinicians and staff are statistically significant at p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively

Results in Table 7 show that overall, staff is more positive about secure messaging than clinicians. Both clinicians (72%) and staff (80%) describe the positive impact of secure messaging on patient satisfaction and a majority of both clinicians (56%) and staff (87%) agree that secure messaging makes communication with patients more efficient. However, there are some significant differences: nearly three-quarters of staff think that secure messaging saves them time, while only 21% of clinicians do. Only 13% of staff thinks that secure messaging has a negative impact on their workflow while 33% of physicians do. Finally, 73% of staff agrees with the statement that secure messaging makes their life easier while only 14% of clinicians do. Overall, clinicians (52%) are moderately satisfied with secure messaging but staff is more positive (87%).

4. Discussion

Secure messaging is a relatively new health information technology. Most clinics have only relatively recently implemented the technology that allows patients to access their medical records and to send secure messages to their healthcare providers. Secure messaging is similar to e-mail and it has many of the same advantages and disadvantages.

Secure messages and their replies can be short and fast. One of the main advantages is that secure messaging allows for a-synchronous communication: patients, clinicians and staff can send or reply to messages when it is most convenient for them. This allows patients who work on a night shift to send a message in the middle of the night, and it allows a clinician to respond to a message in between two patient visits. Just as e-mails, secure messages can be convenient because they leave a “paper trail”. For example, patients can read back the message with instructions that they have received from their physician.

In most clinics, secure messaging is intended for the following purposes: to send a message about a non-urgent, medical issue, laboratory tests, and medications or as a follow-up to an office visit. In most clinics, secure messages are normally not intended for billing questions, medication refills, scheduling appointments, or for asking questions about family members, however, sometimes patients use it for those purposes.

Secure messages also share many of the disadvantages of e-mail messages. For example, volume plays an important role: it makes a huge difference whether you start the day with 2 or 20 messages in your inbox. Clinicians with high message volume (clinics 1 and 2, see Table 1) have more complaints about secure messaging adding to their workload than clinicians in clinics with low volume (see Table 4). Most clinicians have become very adept at responding to secure messaging, for example by using templates or keeping replies very short. But it is not writing the reply itself that takes up most of the time. Before a clinician replies to a message he or she has first to do the research: look up the patient’s problem list, history, medications and/or allergies, etc. and that can add to the time to reply to a message. Even if it takes only 6 minutes to do all of those activities, this means that replying to 10 messages adds up to an hour of work.

Another disadvantage of secure messaging is the lack of contextual information, which is important in patient-clinician communication. Clinicians (and staff) mention the lack of information about a patient’s composure, their gestalt, and their functional status when compared to an office visit or even the information that they receive over the phone. Finally, secure messages have – just as e-mails can – the potential to interrupt the clinical workflow. In particular, messages that bounce around in a team, without anyone clearly knowing what the status of the message is and who is responsible for it, can interrupt workflows.

4.1. Secure messaging workflow facilitators and barriers for clinicians, staff and patients

Examining the facilitators and barriers described by clinicians, staff and patients, we see some interesting patterns. Clinicians are ambivalent about secure messaging, identifying slightly more barriers (on average 4.1 per interview) than facilitators (on average 3.7 per interview). Clinic staff members have a more positive view of secure messaging, mentioning facilitators (3.3) more often than barriers (2.4). Patients’ views were very positive, except in the area of usability.

All three groups indicated that communication via secure messaging makes it easier for patients to reach the clinic and share information. All agreed that secure messaging makes patients comfortable and improves their relationship with the clinic. Patients also mentioned that it helps them to remember topics that they want to discuss with the clinic and to organize their thoughts. However, many clinicians and staff perceive that secure messaging is more beneficial to patients than it is to them.

INTERVIEWER: Is [secure messaging] more useful for the patients or for you or [the physician]?

MA: I think the patients [because it’s an] easier way to communicate with their doctor … A lot of them say they’re not waiting forever to try and get a live person. (Clinic 1 MA)

Both clinicians and staff stated that messages from patients can be ambiguous or complicated. Triage nurses prefer to speak to the patient on the phone, so they can efficiently gather information by asking questions and can also glean useful information from the patient’s tone of voice. Both clinicians and staff become frustrated when patients fail to check their secure messages, ending the communication unexpectedly.

All three groups identified facilitators for patients related to the organization of work—such as the fact that patients do not have to wait on hold or “play phone tag:” “You’re not sitting on a phone or waiting for someone to call you back and you’re not there. So I see from a patient standpoint, it’s good” (Clinic 1 PA). Nurses and staff also appreciate this aspect of secure messaging, stating that it is easier to address some simple patient issues by secure messaging instead of trying to reach the patient by phone. Providers did not perceive this as an advantage, perhaps because they do not typically spend as much time on the phone with patients. Patients mentioned that secure messaging gives them flexibility to communicate with the clinic at their convenience. Clinicians also like the asynchronous nature of secure messaging, which allows them to efficiently address messages as time permits during the work day, for example in between patient visits. However, some providers feel there is a risk that secure messaging could require increasing amounts of their personal time.

[It’s] another way that you feel like the electronic medical record has invaded your soul and life. I can be MyChart messaging patients all night long if I wanted to, honestly, at home, whereas, with a phone call, I can’t. So that’s a difference. So for people that don’t have a great work-life balance, that’s not the best thing for them. (Clinic 4 Physician)

In addition, all three groups prefer secure messaging to phone calls at least some of the time, finding that it reduces their workload and makes workflows more efficient. Clinicians and staff both feel that secure messaging can reduce office visits or nurse visits, as care (particularly follow-up care) is provided without requiring patients to come to the clinic. However, clinicians and staff agreed that some of the messages do not contain sufficiently useful clinical information. Clinicians also described various ways that patients use secure messaging inappropriately, such as sending very long messages, messages with too many issues, or several messages in a short period of time. Overall, providers feel that secure messaging shifts work from nurses to providers, increasing their workload and lengthening their work day.

[In] the last three years, there has been that growing cry from the practitioners to say I shouldn’t be doing this at 8:00 to 9:00 at night at home … to get things going for the next day and not have that accounted into my work week because now I’m working 60 hours a week again. (Clinic 1 Physician leader)

Several clinics developed workflows aiming to redistribute the work by having nurses and staff address messages without involving the providers whenever possible. Clinicians reported that this system works but not perfectly. Providers complain that too many messages are routed to them instead of being handled by nurses or staff. One key issue is provider compensation: providers are not paid directly for the time spent addressing secure messages, and they, therefore, perceive it as extra work. In contrast, patients are sometimes able to receive healthcare services (e.g., a prescription) without visiting the clinic or paying a co-pay, which is a benefit to them in terms of saved time and money.

I would guess that the dissatisfaction from the physician’s standpoint has to do with the fact that it’s [work that isn’t compensated]. And that has to do a lot with the patient satisfaction too. If you charged for it, and [patients] had to pay [for] it, I think their attitude would change. (Clinic 4 Physician)

Communication and information flow is one of the most often mentioned workflow facilitators of secure messaging for all three groups (clinicians, staff and patients). Secure messaging allows for asynchronous communication which allows all three groups to deal with messages when it suits them best. Clinicians mentioned that secure messaging improved workflow by opening another line of communication for patients to contact the clinic. However, this is also the reason secure messaging can act as a barrier to workflow: it adds an extra communication channel in addition to already existing communication channels (postal mail, telephone and fax). For example, a patient can order a medication refill through the patient portal, and if s/he does not receive a reply quickly enough, s/he can pick up the phone and ask for the refill by phone or send a secure message. The patient can also call or go to the pharmacy and ask for a refill which would result in another request either by phone or fax from the pharmacy (channel switching). The same request for a refill through multiple channels can have a negative impact on workflow of clinicians and staff. Finally, secure messaging can be a barrier to communication and information flow because secure messages often lack the context needed to address the issues described in the message. That means that clinicians and/or staff have to ask for clarification (either by secure messaging or by phone), before they can address the issue.

The asynchronous characteristic of secure messaging helps with the organization of work for clinicians, staff and patients, as it avoids having to play phone tag, in which the clinic calls the patient back, and if the patient does not answer the phone, have to leave a message asking the patient to call the clinic back (due to privacy regulations (HIPAA) in the USA, clinics are not allowed to leave medical information in a voice mail).

With regard to the amount of work, for clinicians and staff, secure messaging can act both as a facilitator and barrier. Responding to messages adds work. However, according to providers, secure messaging improves the clinic’s overall efficiency, because messages can be addressed quicker, especially as compared to having to play phone tag, which can especially be an issue for nurses and MAs.

4.2. Impact of secure messaging on quality of care, patient safety and satisfaction

Results in table 8 show that clinicians, staff and patients think that secure messaging has a positive impact on quality of care and patient safety and that clinicians and staff think that it increases patient satisfaction. Overall, all three groups are satisfied with the secure messaging technology.

Half of clinicians described the positive impact of secure messaging on quality of care, patient safety and patient satisfaction. Clinicians stated that the ease of communication encourages patients to more often share information useful for their care. Also, some patients review their medical records on a patient portal and send the clinic messages to correct errors. Satisfaction with the technology was a facilitator mentioned by many clinicians. Providers reported that they appreciated being able to address patient issues without bringing every patient into the clinic.

However, some clinicians and staff also saw some pitfalls to secure messaging. For example, one physician was concerned about possible negative effects of the teamwork approach to secure messaging.

I think it does have some impact, negative impact on patient safety, again, when there’s multiple encounters or multiple threads open that you don’t even realize. Usually those are just a matter of answering questions, so it’s more confusing than dangerous… So if my PA has addressed it in a separate encounter, and I don’t realize that, and I address it or vice versa, we have run into that a couple of times, you could get two slightly different instructions, you know, there’s more than one way to skin a cat kind of thing. Neither of them are dangerous, but then it becomes confusing. Or you might get two orders for slightly different medicines or something like that. I haven’t had too much trouble with that, because my PA and I are both pretty good about looking and checking. But there is always that potential if you’re not diligent. (Clinic 1 MD)

Finally, several nurses reported that they appreciated receiving messages from grateful patients.

People will just send in a message saying, hey, thank you for helping us out…, or helping me out or my kid or my mom or whatever it is. And that’s nice, because then we can just quick read it and know that, yay, we helped someone. (Clinic 4 RN)

4.3. Differences between cases (clinics)

As can be seen in Tables 4–6, there are many similarities in workflow facilitators and barriers across the clinics, but there are also differences. Most of the differences are related to the volume of messages and the way work is organized in the clinics (see Table 2). This is most obvious in clinic #2, a single physician practice, in which the high volume of secure messages is handled by the physician. This substantially adds to his workload (see Table 4). Clinic #1 also has a relatively high volume of messages, but the clinic is in the advanced stage of medical home implementation, which means that much of the secure messaging workload is distributed among the different team members. Nevertheless, the relatively high volume of messages also impacts the workload of clinicians and, to a lesser extent, staff members. The high volume of messages in clinics 1 and 2 also has an impact of the organization of work. In clinics with a lower volume (clinics 3, 4 and especially 5), clinicians have fewer complaints about the impact of secure messaging on their workflow. However, it should be noted that –apart from differences between the clinics- there are also differences within clinics. Some providers are very enthusiastic about secure messaging and the possibility that secure messaging can have on patient engagement. However, in the same clinic, other providers (sometimes because they are not compensated for secure messaging activities) hardly use secure messaging and may ask patients to come in for office visits.

4.4. Study limitations and strengths

The goal of this study was to examine the impact of secure messaging on workflow in small- and medium-size clinics. This focus limits the sample size. For example, one clinic in our study had one physician, one clinic manager, one MA, one receptionist and one billing person. For that reason, we used a multiple case study design that included several small- and medium-size clinics. However, the number of cases in this study is limited (5 cases) and, overall, the sample sizes remain small; this makes it difficult to generalize the findings of our study. Another limitation is that 4 of 5 clinics used the same vendor’s EHR and patient portal. On the one hand, that allowed us to compare user experiences with the same portal (Lanham, Leykum, & McDaniel, 2012), but on the other hand, it limits the results to two types of EHR and patient portals and makes it difficult to generalize our results to other EHR systems or patient portals. Finally, the study had a cross-sectional design and, therefore, it is difficult to establish causal relationships. Although the overall survey response rate was satisfactory (83%, 118 respondents), only 53 clinicians and 14 staff members had experience with secure messaging and filled out the survey questions about secure messaging. This relatively small sample size makes it difficult to generalize the results. In addition, we interviewed only patients that use secure messaging; therefore, our results cannot be generalized to all patients, in particular non-users of secure messaging.

A strength of the study is the multiple case study design with mixed data collection methods. The observation and interview data were analyzed to create process maps for the 5 cases. These process maps allowed us to better understand similarities and differences in secure messaging workflow. The interviews with all end-users (clinic managers, physicians, nurses, staff and patients) provided us with rich information about the secure messaging processes in the different clinics and about facilitators and barriers to the secure messaging workflow in each clinic from different perspectives. Results of the survey provided us with an overall impression of user (clinicians and staff) experience with secure messaging. Results of our analysis of data collected with different methods (observations, interviews and survey) were triangulated to ensure a high level of internal validity (Dubé & Paré, 2003). For example, results of our observations and interviews showed that volume of secure messages does have an impact on workload. Clinics 1 and 2 have a substantially higher message volume (see Table 1) than clinics 3, 4 and 5. In clinics 1 and 2, the amount of work is more often mentioned as a workflow barrier than in clinics 3, 4 and 5. Overall, very few clinicians (14%) agree with the statement that secure messaging reduces their workload (Table 7). Future research could extend our results and quantitatively assess the impact of contextual clinic factors (e.g., clinic size, volume of messages) on workflow and perceptions of clinicians, staff and patients.

4.5. The future of secure messaging

Results of this study show that patients like secure messaging very much, suggesting that it is not likely to be discontinued. Several studies have found that, in general, patients are satisfied with secure messaging (de Lusignan et al., 2014; Haun et al., 2014; Mold & de Lusignan, 2015). Clinicians (and staff) sometimes complain about the impact of secure messaging on their workload, but one of the important reasons for that is that under the current fee-for-service system, secure messaging activities are not compensated. However, with the change to value-based care, it may be advantageous for clinics and the clinicians and staff who work there, to shift work to secure messaging and, thereby, reduce patient visits, which can be relatively expensive. An intermediate solution may be e-visit, which deserves to be studied in depth as little is known about this technology-mediated care process and its impact on workflow, clinicians, staff and patients.

Conclusion

Providing patients with the option to share information with their clinicians electronically is a recent addition to health IT. The literature contains only limited evidence that health outcomes are improved by the introduction of patient portals. However, some evidence indicates that these health IT applications may improve process measures, such as greater adherence, better self-care, improved patient-provider communication, and patient satisfaction. The results of this study support findings in the literature that patients sharing their information with clinicians electronically can facilitate communication, improve the organization of work, reduce workload, and increase patient satisfaction.

However, results also show that some of these same dimensions (e.g., amount of work) can be barriers. In other words, implementation of secure messaging can have benefits, but can also hinder workflow and, for example, increase physician workload. In their systematic review on patient portals and the relationship with health outcomes, Goldzweig et al. (2012) concluded that: “Health IT [including secure messaging] is a tool, and if implemented by itself may have modest or even no measurable effect, but health IT can enable the implementation of more comprehensive programs that have meaningful effects on quality of care” (p. 35). In addition, our findings show that poor usability of the health IT applications plays an important role as a significant workflow barrier.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ: Carayon: PI, contract No. HHSA 290-2010-00031I) and by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of AHRQ. We thank Abt Associates, and in particular Deborah Deitz and Andrea Hassol for their logistic and other support for this study. We especially thank the managers, clinicians and staff of the five clinics for participating in this study.

Footnotes

HIPAA means that electronic communication between patients and providers needs to meet the following requirements: Healthcare messaging and personal messaging are segregated; special authorization and authentication for accessing messages through a personal invitation process is required and access to messages is password-protected; messages are encrypted in transit; data on mobile devices is encrypted; personal Health Information (PHI) is removed from screen notifications; message histories are fully archived; there are auditing capabilities; if photo sharing is allowed, photos taken are not added to devices’ camera rolls, and they are encrypted, secured, and auditable; copying or leaking of PHI is made very difficult (e.g. copying on a clipboard is not possible); if devices are stolen it should be possible to instantly lockout and erase data. All of this means that communication between patients and providers using a personal e-mail account for sending a message, or sending a message through an app (e.g. Facebook) is not conform HIPAA regulation.

References

- Boukus ER, Grossman JM, & O’Malley AS (2010). Physicians slow to e-mail routinely with patients. Center for Health System Change Issue Brief, (134). Retrieved from http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/1156/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JM, Elliott S, & Firek A (2009). Initial experience with patient-clinician secure messaging at a VA medical center. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 16(2), 267–270. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Cartmill R, Hoonakker PLT, Hundt AS, Karsh B-T, Krueger D, … Wetterneck TB (2012). Human Factors Analysis of Workflow in Health Information Technology Implementation. In Carayon P (Ed.), Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety (2nd ed., pp. 507–521). Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Hoonakker PLT, Cartmill RS, & Hassol A (2015). Using Health Information Technology (IT) in Practice Redesign: Impact of Health IT on Workflow. Patient-Reported Health Information Technology and Workflow (Publication No. 15-0043-EF). Retrieved from Rockville, MD: https://healthit.ahrq.gov/ahrq-funded-projects/using-health-information-technology-practice-redesign-impact-health-information-technology-on-workflow-ma/final-report [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS). (2012). Stage 2: Eligible professional meaningful use core measures. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/downloads/Stage2_EPCore_17_UseSecureElectronicMessaging.pdf

- Chen C, Garrido T, Chock D, Okawa G, & Liang L (2009). The Kaiser Permanente Electronic Health Record: transforming and streamlining modalities of care. Health Aff (Millwood), 28(2), 323–333. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lusignan S, Mold F, Sheikh A, Majeed A, Wyatt JC, Quinn T, … Rafi I (2014). Patients’ online access to their electronic health records and linked online services: a systematic interpretative review. BMJ Open, 4(9), 1–11. doi:doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter EN, Fields S, Rdesinski RE, Sachdeva B, Yamashita D, & Marino M (2016). Patient–Provider Communication: Does Electronic Messaging Reduce Incoming Telephone Calls? The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 29(5), 613–619. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.05.150371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé L, & Paré G (2003). Rigor in Information Systems Positivist Case Research: Current Practices, Trends, and Recommendations. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 597–636. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt KM (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. [Google Scholar]

- Goel MS, Brown TL, Williams A, Cooper AJ, Hasnain-Wynia R, & Baker DW (2011). Patient reported barriers to enrolling in a patient portal. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 18(Suppl 1), i8–i12. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldzweig CL, Towfigh AA, Paige NM, Orshansky G, Haggstrom DA, Beroes JM, … Shekelle PG, . (2012). Systematic review: secure messaging between providers and patients, and patients’ access to their own medical record. Evidence on Health Outcomes, Satisfaction, Efficiency and Attitudes. Washington, DC: Department of Veteran Affairs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover F Jr., Wu HD, Blanford C, Holcomb S, & Tidler D (2002). Computer-using patients want Internet services from family physicians. J Fam Pract, 51(6), 570–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haun JN, Lind JD, Shimada SL, Martin TL, Gosline RM, Antinori N, … Simon SR (2014). Evaluating User Experiences of the Secure Messaging Tool on the Veterans Affairs’ Patient Portal System. J Med Internet Res, 16(3), e75. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs J, Wald J, Jagannath YS, Kittler A, Pizziferri L, Volk LA, … Bates DW (2003). Opportunities to enhance patient and physician e-mail contact. Int J Med Inform, 70(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoonakker PLT, Carayon P, & Walker J (2010). Measurement of CPOE end-user satisfaction among ICU physicians and nurses. Applied Clinical Informatics, 1(3), 268–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SJ, Moyer CA, Cox DT, & Stern DT (2003). Effect of a triagebased e-mail system on clinic resource use and patient and physician satisfaction in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18(9), 736–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzen C, Solan MJ, & Dicker AP (2005). E-mail and oncology: a survey of radiation oncology patients and their attitudes to a new generation of health communication. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 8(2), 189–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, & McDaniel RR (2012). Same organization, same electronic health records (EHRs) system, different use: exploring the linkage between practice member communication patterns and EHR use patterns in an ambulatory care setting. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA, 19(3), 382–391. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee F, Teich JM, Spurr CD, & Bates DW (1996). Implementation of physician order entry: user satisfaction and self-reported usage patterns. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 3(1), 42–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong SL, Gingrich D, Lewis PR, Mauger DT, & George JH (2005). Enhancing doctor-patient communication using email: a pilot study. J Am Board Fam Pract, 18(3), 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liederman EM, Lee J, Baquero V, & Seites P (2005). Patient-physician web messaging: the impact on message volume and satisfaction. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(1), 52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40009.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C-T, Wittevrongel L, Moore L, Beaty BL, & Ross SE (2005). An Internet-Based Patient-Provider Communication System: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res, 7(4), e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]