Abstract

Background

African American adults suffer disproportionately from obesity-related chronic diseases, particularly at younger ages. In order to close the gap in these health disparities, efforts to develop and test culturally appropriate interventions are critical.

Methods

A PRISMA-guided systematic review was conducted to identify and critically evaluate health promotion interventions for African Americans delivered in barbershops and hair salons. Subject headings and keywords used to search for synonyms of ‘barbershops,’ ‘hair salons,’ and ‘African Americans’ identified all relevant articles (from inception onwards) from six databases: Academic Search Ultimate, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science (Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index). Experimental and quasi-experimental studies for adult (> 18 years) African Americans delivered in barbershops and hair salons that evaluated interventions focused on risk reduction/management of obesity-related chronic disease: cardiovascular disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes were included. Analyses were conducted in 2020.

Results

Fourteen studies met criteria for inclusion. Ten studies hosted interventions in a barbershop setting while four took place in hair salons. There was substantial variability among interventions and outcomes with cancer the most commonly studied disease state (n = 7; 50%), followed by hypertension (n = 5; 35.7%). Most reported outcomes were focused on behavior change (n = 10) with only four studies reporting clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Health promotion interventions delivered in barbershops/hair salons show promise for meeting cancer screening recommendations and managing hypertension in African Americans. More studies are needed that focus on diabetes and obesity and utilize the hair salon as a site for intervention delivery.

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42020159050.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-021-11584-0.

Keywords: African Americans; Chronic diseases, obesity; Cancer; Cardiovascular disease; Type 2 diabetes mellitus; Health promotion; Barbershops; Hair salons; Systematic review

Background

African Americans, the second largest minority group, account for 13.4% of the United States (U.S.) population [1]. African Americans are disproportionately burdened by obesity and related chronic diseases such as heart disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes resulting in higher rates of morbidity and mortality than non-Hispanic whites (NHW) [2]. African Americans have the second highest prevalence for obesity and diabetes (46.8 and 12.7%, respectively) of any racial/ethnic group [3]. African Americans have two times the risk of having stroke or dying from cardiovascular disease, and have 50% more risk of having hypertension than NHW [4]. African Americans are at higher risk of developing colorectal cancer and their mortality rates for multiple myeloma and stomach cancer are double that of NHW [5]. Moreover, prostate cancer mortality risk is two times as high for African American men as compared to NHW men; while African American women have higher risk of death from breast and cervical cancers than NHW [5]. Many social determinants of health (wage gaps, substandard education and healthcare, and unethical housing policies) are associated with health disparities among African Americans [6, 7]. Historically, African Americans have had mistrust in the medical and research community making them less likely to see a primary care doctor and participate in health promotion research [8–11]. Strategies to engage African Americans in health promotion programs must consider cultural appropriateness when designing and implementing effective health promotion interventions.

By working with community partners that deliver services to African Americans and trusted health care providers that are members of the African American community, interventionists can identify socioeconomic risk factors and barriers to healthcare utilization, facilitate coordination of care and resources, and implement evidence-based interventions to address health disparities. Engaging African Americans in health promotion interventions has been challenging likely in part due to a lack of consideration of the role culture plays in components such as intervention attendance and adherence. Typically, interventions are located in settings that have been perceived historically as inaccessible or excluding to African Americans further exacerbating health inequities. Toward this end, public health practitioners have turned to trusted community-based settings as sites for health promotion education and programming.

Health behavior researchers and programmers have utilized faith-based organizations to reach the African American community [12, 13]. The church has historically served as a source of refuge where members and the African American community at large can gather for non-religious purposes such as socialization and civic and political activities. As an integral part of the communities in which they reside, the church is often tasked with community outreach initiatives as well as economic development opportunities for local residents. Researchers and programmers can benefit from including core African American cultural constructs such as religiosity and social support/structure offered by the church in their interventions [14]. Furthermore, leveraging the social network by engaging leaders in the church that can reinforce participation or model the desired healthy behavior can be advantageous [15]. Integrating biblical texts and spiritual elements into the intervention increases program effectiveness [14]. For all the progress in reaching the African American community, there are limitations with church-placed and church-based interventions. Young African American adults and African American men are less likely than older African Americans and African American women to attend church services regularly [16]. Also, black churches have found themselves inundated with projects and competing interests making it difficult to prioritize health promotion programs [17].

Akin to the church, barbershops and hair salons are staples in the African American community. They impart important African American cultural constructs such as communalism and expressiveness [18]. Sociocultural influences of behavior can be explored and leveraged through the barbershop and hair salon. Barbershops and hair salons serve as sources of entrepreneurship; therefore, owners, barbers, and stylists alike are respected by members of the African American community. Because they are highly accessible, barbershops and hair salons have been involved in health promotion activities such as formative research, subject recruitment, and delivery/implementation of interventions [18–25]. Because African American men have traditionally been a difficult group to engage, barbershop health promotion has increased in popularity [26]. Oftentimes, African American men hang out for hours at the barbershop beyond their service visit. During this time one can network for a job, buy or sell products, advertise a business, watch movies or sports, discuss or get advice on personal and family affairs, and participate in other recreation (play board/video games, card, dominoes, etc.) [26].

Like their male counterparts, African American women maintain a high-level of engagement with the hair salon for many of the same reasons. Due to the unique and close relationship African American women have with their stylist, researchers can find opportunity in delivering interventions in hair salons and to a further extent by hair stylists [27–32]. Hair stylists are trusted by their clients and therefore serve as a confidante, a reliable source of information, and oftentimes as a close companion. This trust is in stark contrast to the mistrust of the medical system and research community common among African Americans. Because of this trust/mistrust, inaccessible quality healthcare, and lack of culturally appropriate interventions, African American woman are less likely to have a primary care provider [33]. However, it is more common for them to have a regular hair stylist illustrating the significance of routine hair care service [33]. Oftentimes hair care for African American women can require regular, lengthy visits to the salon thereby providing a captured audience suitable for health behavior interventions [34].

There is a paucity in the literature for systematic reviews that consider the role of the setting in engaging African Americans in health promotion. Among those, most have assessed cultural tailoring of evidence-based interventions (race concordance of interventionist, spirituality, etc.) [35–39]. A few have examined the role of churches, barbershops, and hair salons for recruitment of research participants into clinical trials [40, 41]. One synthesis of the literature explored barbershop and hair salon health promotion, but African Americans were not the primary population of interest [19]. Similarly, a 2015 qualitative systematic review described barber-led interventions targeted for African American men without inclusion of stylist-led interventions targeted for African American women [26]. This is the first systematic review of the effectiveness of barbershop and hair salon health promotion interventions for African Americans that elucidates the quality of evidence of these interventions. Characteristics of effective interventions addressing the leading obesity-related chronic disease (heart disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes) health disparities for African Americans will be identified.

Methods

Literature search

This systematic review was conducted according to the guidelines set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [42]. The study was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) in 2020 (CRD42020159050). The detailed prespecified protocol has been previously published [43]. Seven databases (Academic Search Ultimate, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, PsychInfo, PubMed, Web of Science, and ProQuest Dissertations from inception to October 2019) were queried following comprehensive search strategies developed in consultation with a medical librarian (Additional file 1). Controlled vocabulary terms in databases (including MeSH and Emtree) and keywords were used in the search relevant to the target population (African Americans) and intervention component (delivery site- barbershops and/or hair salon) resulting in the following terms: “African American,” “Black American,” “African Ancestry,” “barber,” “barbering,” “beautician,” “beauty culture,” “cosmetologist,” “hair,” “hairdresser,” “hairstylist,” “stylist,” “beauty shop,” “beauty salon,” “hair salon,” and “salon.” The final search was conducted on October 08, 2019.

Inclusion criteria/study selection

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Adult African Americans were the target population for the intervention.

The intervention was delivered in a U.S. barbershop or hair salon.

The study evaluated an intervention aimed at reducing risk factors or improving health outcomes of obesity and/or related chronic conditions (i.e. cardiovascular disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes).

Only interventional study designs were included. Studies were excluded if participants were children/adolescents (aged < 18 years), the intervention took place outside of the U.S., or if the article was published in a language other than English.

Identification of eligible articles

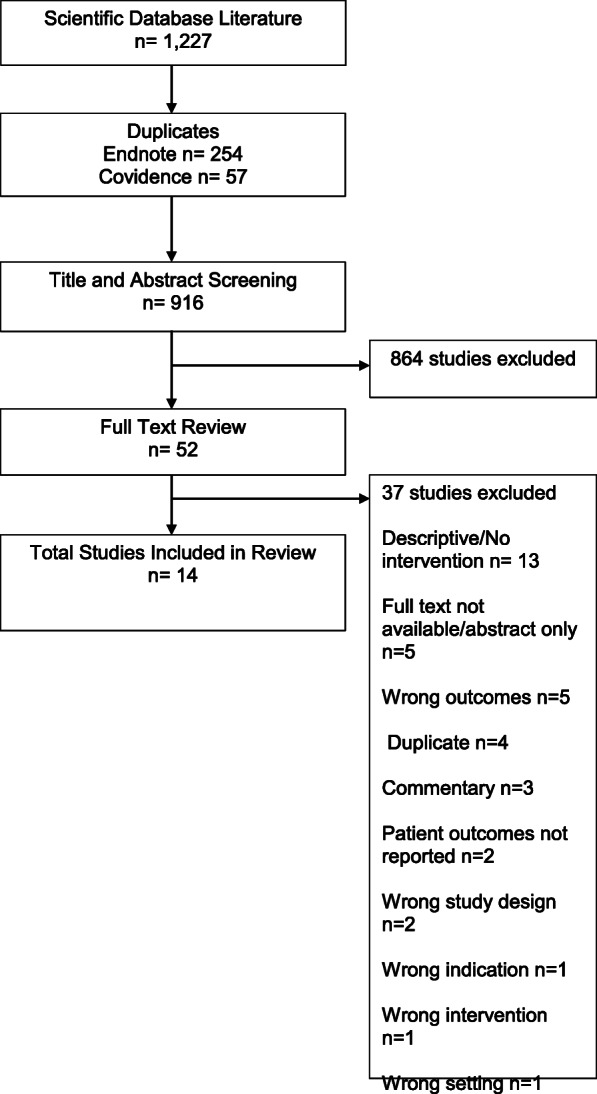

Figure 1 displays the screening and inclusion process depicted in a flow diagram. A search of the electronic databases yielded 1227 records by study author JM. After duplicates were removed, 973 records were uploaded to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne Australia). Fifty-seven duplicates were removed, and 916 articles remained. Titles and abstracts were reviewed in triplicate by three of the study authors (KP, PR, and FM) resulting in 57 articles for full-text review. Study authors KP and PR independently reviewed the full text of each article against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. This resulted in 13 articles for inclusion in this review. One article reported on 2 studies, 2 articles are from the same study, but report different outcomes, and 2 articles are from the same study with one article reporting outcomes after extending the intervention [21, 29, 30, 44, 45].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was completed in duplicate by study authors KP and PR using a customized Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database (Additional file 2) [46]. Data reports were reviewed for accuracy by FM. Data variables extracted from each article included: first author’s last name, year of publication, article title, sample size, age range or mean age, gender, socioeconomic status of participants, geographic location, disease focus, study design, study setting, intervention/control description, intervention duration, follow up time points, if a community-based participatory research approach was employed, interventionist, if culturally-sensitive strategies were implemented, if incentives were given, theoretical frameworks/models, barbershop/hair salon recruitment strategies, and study outcomes and results (noting significance). For studies where the barber/stylist was the interventionist, data on intervention training and strategies for intervention fidelity were also collected. Due to the heterogeneity of studies and outcomes, data were analyzed and synthesized for presentation narratively and in tables in 2020. Two authors (KP and PR) independently evaluated the quality of evidence using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP) to increase inter-rater reliability and reduce risk of bias [47, 48]. Articles were given a global rating by each of the two reviewers of weak, moderate, or strong based on the six component ratings of selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection, and withdrawals/dropouts. The two reviewers discussed global ratings for each article and a final decision of both reviewers was recorded in a REDCap database (Additional file 3).

Results

Study characteristics

Because one article reported outcomes for two studies [21], 14 studies are included in the final review. Characteristics of the 14 studies are presented in Table 1. Studies were published between 2007 and 2019. Seven studies were randomized control trials (RCTs) (six cluster RCTs and 1 RCT), four were pretest-posttest (three 2- group and one 1-group), two were nonrandomized feasibility studies, and one (1 group) posttest only study. Sample sizes varied widely from 20 to 1297 participants. Mean age of study participants ranged from 37 to 57.4 years, but ranges were wide with participants aged 18 to 88. Socioeconomic status (SES) was reported by all but two studies. Participants in three studies were reported as having only a high school education or less, low-income, and/or mostly uninsured [20, 54, 55]. Studies were mostly conducted in large urban/metropolitan cities with only one in a rural area [20]. Seven interventions focused on outcomes related to cancer [27, 29, 50–53, 55], five on cardiovascular disease (i.e. blood pressure) [21, 44, 45, 49], one on type 2 diabetes [30], and one on obesity [20]. Barbershops accounted for the majority of study settings (n = 9) [21, 44, 45, 50–53, 55, 56], with four studies taking place in hair salons [20, 27, 29, 30]. Interventions taking place in barbershops targeted men (n = 9) [21, 44, 45, 50–53, 55, 56] while those in hair salons targeted women (n = 4) [20, 27, 29, 30].

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| First Author, Year, Ref |

Title | Sample Size | Mean Age/ Age Range |

SES | Geographic Location | Study Design | Disease State/Focus | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbershops as Hypertension Detection, Referral, and Follow-Up Centers for Black Men | n = 94 | 40–60 | mostly insured or have access to public health care system | Dallas, Texas | Non-Randomized Feasibility | Cardiovascular Disease | Barbershop |

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbershops as Hypertension Detection, Referral, and Follow-Up Centers for Black Men | n = 321 | 40–60 | mostly insured or have access to public health care system | Dallas, Texas | Non-Randomized Feasibility | Cardiovascular Disease | Barbershop |

| Wilson, 2008 [27] | Hair Salon Stylists as Breast Cancer Prevention Lay Health Advisors for African American and Afro-Caribbean Women | n = 1185 | 38 | Not reported | Brooklyn, New York | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Cancer | Hair Salon |

| Holt, 2010 [49] | Cancer Awareness in Alternative Settings: Lessons Learned and Evaluation of the Barbershop Men’s Health Project | n = 163 | 45+ | Not reported | Birmingham, Alabama |

2 group Pretest-Posttest |

Cancer | Barbershop |

| Johnson, 2010 [20] | Beauty Salon Health Intervention Increases Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in African-American Women | n = 20 | 18–70 | > 50% (11/20) High School Diploma | Rural South Carolina | 2 group Pretest-Posttest | Obesity | Hair Salon |

| Luque, 2011 [50] | Barbershop communications on prostate cancer screening using barber health advisers | n = 40 | 53 | mean education = 14 years, mean household income <$70 k, 78% privately insured | Tampa, Florida |

1 group Posttest only |

Cancer | Barbershop |

| Sadler, 2011 [29] | A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase Breast Cancer Screening Among African American Women: The Black Cosmetologists Promoting Health Program | n = 984 |

40.6 20–88 |

mostly college educated (52% some college, 34% complete college) | San Diego, California | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Cancer | Hair Salon |

| Victor, 2011 [27] | Effectiveness of a Barber-Based Intervention for Improving Hypertension Control in Black Men | n = 1297 |

Intervention: 49.5 Control: 51.2 |

85% middle income and insured | Dallas, Texas | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Cardiovascular Disease | Barbershop |

| Odedina, 2014 [51] | Development and assessment of an evidence-based prostate cancer intervention programme for black men: the W.O.R.D. on prostate cancer video | n = 142 | 50–59 | > 50%: <$20 k, H.S. diploma, had insurance, had PCP | Florida |

1 group Pretest-Posttest |

Cancer | Barbershop |

| Sadler, 2014 [30] | Lessons learned from The Black Cosmetologists Promoting Health Program: A randomized controlled trial testing a diabetes education program | n = 984 |

40.6 20–88 |

mostly college educated (52% some college, 34% complete college) | San Diego, California | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Type 2 Diabetes | Hair Salon |

| Frencher, 2016 [52] | PEP Talk: Prostate Education Program, Cutting Through the Uncertainty of Prostate Cancer for Black Men Using Decision Support Instruments in Barbershops | n = 120 | 40+ | majority income<$24 k; uninsured, college or more | South Los Angeles, California |

2 group Pretest-Posttest |

Cancer | Barbershop |

| Cole, 2017 [53] | Community-Based, Preclinical Patient Navigation for Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Older Black Men Recruited From Barbershops: The MISTER B Trial | n = 731 |

57.4 50+ |

mean annual income = $16,726, 1/3 < High School diploma, ~ 50% unemployed | New York, New York | Randomized Control Trial | Cancer | Barbershop |

| Victor, 2018 [45] | A Cluster-Randomized Trial of Blood- Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops | n = 319 |

Intervention: 54.4 Control: 54.6 35–79 |

mostly college educated, have regular medical provider and insured | Los Angeles, California | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Cardiovascular Disease | Barbershop |

| Victor, 2019 [46] | Sustainability of Blood Pressure Reduction in Black Barbershops | n = 319 |

I: 54.4 C: 54.6 35–79 |

mostly college educated, have regular medical provider and insured | Los Angeles, California | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Cardiovascular Disease | Barbershop |

Interventions

Table 2 summarizes characteristics of the interventions. All studies evaluated barbershop/hair salon-based health promotion interventions aimed at reducing risk factors for or improving health outcomes of obesity-related chronic conditions in African Americans. Interventions were extremely heterogenous in mode of delivery, duration, and content. Most interventions were delivered in-person, two were delivered via media (video/DVD) [50, 52], and one was delivered via phone calls [55]. Barbers and stylists served as the interventionists in most cases. In two studies, when not serving as the primary interventionist, barbers and stylists supported client engagement with the interventionist, a medical professional/pharmacist [44, 45]. One study employed African American actors to portray barbers, barbershop clients, and doctors in a video-based intervention [52]. Two interventions were led by the researcher/research staff and one by trained counselors and community health workers [21, 50, 55]. Intervention duration varied from 25 min (video) to 14 months. The use of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) was reported in three studies [21, 27]; two studies cited Health Belief Model [29, 30]; one study employed the Personal Integrative Model of Prostate Cancer and the Health Communication Process model [52], one study utilized peer learning [44], and one study adapted a model from the AIDS Community Demonstration Project [56]. Only five studies explicitly stated using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach [27, 29, 50, 51, 53].

Table 2.

Intervention Characteristics

| Author, Year | Setting | Intervention | Comparison | Interventionist | Duration/ Data Collection Time Points |

Theoretical Framework/ Model |

CBPR Approach | Recruitment Strategies | Culturally Adapted Strategies | Incentives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbershop |

Staff delivered intervention- Physician referral for follow up with BP report card for ongoing feedback Role model stories depicting successful risk reduction strategies adopted by hypertensive African American men |

Both groups received written results of the 3 BP screenings and standard recommendations for interval medical follow-up | Researcher/Research Staff |

8 months/ Baseline and post-intervention |

Social Cognitive Theory | Not reported | Not reported | Intervention delivered by African American research assistants and medical/premedical students supervised by an African American nurse |

Barbers Customers |

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbershop | Barbers delivered the intervention- Blood Pressure report cards to be signed by provider and returned to barber | American Heart Association brochures titled High BP in African Americans | Barbers |

14 months/ Post-intervention |

Social Cognitive Theory | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

Barbers Customers |

| Wilson, 2008 [27] | Hair Salon |

Intervention designed to promote stylist’s skills and motivation to provide correct and consistent breast health info to female clients on an ongoing basis. Breast health recommendations included monthly breast self-exams, annual clinical breast exams, and routine mammography for women 40 + . Stylists to promote client skills, self-efficacy, and motivation for engaging in breast health behaviors Written materials for clients on where to get services for breast cancer detection and treatment |

No-treatment control | Hair Stylists |

3 months/ Baseline and 1–3 post-intervention |

Social Cognitive Theory | Yes |

List of salons from targeted neighborhoods generated via phone book listings and internet by zip codes. Randomly selected salons and contacted owners to assess willingness to participate in study. |

No description | Hair Stylists |

| Holt, 2010 [51] | Barbershop |

Health messages about CaP and CRC delivered by barbers to clients. Barbers help with strategies for informed decision making about screening supported by posters, print materials, and videos |

Not reported | Barbers |

3 months/ Baseline and post-intervention |

Not reported | Yes | Barbershops recruited and trained by the community partnership | Community advisory panel developed intervention and recruited barbers | Customers |

| Johnson, 2010 [20] | Hair Salon |

3 scripted motivational sessions during clients’ service appointments encouraging them to adopt healthy behaviors- 1) Role modeling 2) Motivation 3) Check-in and recognition Information packets- 4 pages of info on fruit/vegetable consumption, PA, and water consumption reviewed by dieticians Starter kits- Samples of fruits/vegetables and a bottle of water given at sessions 1 and 3 |

No treatment control at second salon | Hair Stylists |

6 weeks/ Post-intervention |

Not reported | Not reported | Stylists were screened to assess value of evidence-based health and any changes to the stylist’s personal health in the last 12 months. |

Broad overall health changes instead of specific numerical goals with focus on efficacy. Materials reviewed by African American women before study |

Not reported |

| Luque, 2011 [53] | Barbershop |

CaP education materials developed by research team (brochure/poster, video, and Flipchart) tailored for African American men adapted from early detection/screening to informed decision-making for PCS guidelines. Plastic prostate model, barber talking points card, and community resources list |

Not applicable | Barbers |

one session during client visit to barbershop/ post-intervention |

Not reported | Yes |

Community health agency helped identify 2 barbershops. Snowball strategy from initial 2 barbershops resulting in 2 more barbershops. Clients- convenience sample of barbershops |

Education materials tailored for African American men via learner verification and then piloted with African American men. | Not reported |

| Sadler, 2011 [29] | Hair Salon |

Cosmetologists were to engage clients in conversation about adhering to BC screening guidelines for them, family, and friends, and importance of early detection (CBE and mammography) and treatment. A series of eight laminated “Mirror Challenges” were sequentially posted in a corner of the cosmetologists’ mirror. Relevant articles from lay newspapers and magazines trusted by the African American community were laminated and given to cosmetologists. A 3-ring binder of info was used as well. A soft plastic BC model to show how a BC lump felt and string of clay beads to depict various sizes of BC lumps given. BC posters with images of African American women throughout salon. |

Diabetes education intervention identical to BC intervention in all ways but content | Hair Stylists |

6 months/ baseline and 6 months |

Health Belief Model | Yes |

African American church members helped recruit cosmetologists and facilitate meeting with study leader. Clients recruited via African American research assistant or stylists. |

Ancestral storytelling |

Hair Stylists Customers |

| Victor, 2011 [49, 56] | Barbershop |

Barbers offered repeated BP checks during haircuts, gave repeated personalized sex-specific health messages to promote physician follow up Posters with barbershop patrons modeling HTN treatment behaviors and testimonials Patrons with elevated BP recommended to follow up with a physician (or study nurse) Patrons with elevated BP received referral cards to give physicians for feedback and to document patron-physician interaction |

Standard HTN education pamphlets from the AHA written for a broad audience of black men and women | Barbers |

10 months/ Baseline and 10 months |

Adapted from the AIDS Community Demonstration Projects that mobilized community peers to deliver intervention messages (specific action items) with role model stories and made medical equipment available in the daily environment | Not-reported |

Barbershops selected to represent 4 geographic areas > 95% black male clientele > 10 years in business > 3 barbers |

Not-reported |

Barbers Customers |

| Odedina, 2014 [52] | Barbershop |

A prostate cancer education video “Working through Outreach to Reduce Disparity (W.O.R.D.) on Prostate Cancer” Focuses on explaining the risk factors for CaP, how to reduce the risk for CaP, and informed decision making about CaP screening. Barbershop conversation teaches main character importance of CaP prevention (CaP survivor shares his story). As a result, he decides to follow up with doctor. |

Not applicable | African American actors portraying barbers, clients, ministers, and doctors |

25 min/ Baseline and post-intervention |

Personal Integrative Model of Prostate Cancer Disparity (PIPCaD) model Health Communication Process Model |

Not reported | Not applicable |

Using African American actors to model desired behaviors for target population (African American men) Video setting in a barbershop |

Customers |

| Sadler, 2014 [30] | Hair Salon |

Diabetes education intervention to increase diabetes knowledge, change diabetes attitudes, and increase diabetes screening behaviors among African American women. Article references Sadler 2011 with details of BC intervention that is comparable to diabetes intervention with only difference being content. |

BC education intervention identical to diabetes intervention in all ways but content | Hair Stylists |

6 months/ baseline and 6 months |

Health Belief Model | Not reported |

African American church members helped recruit cosmetologists and facilitate meeting with study leader. Clients recruited via African American research assistant or stylists. |

Ancestral storytelling | Hair stylists |

| Frencher, 2016 [50] | Barbershop |

2 Decision Support Instruments in DVD format: VCU- culturally tailored to African American men FIMDM- general audience Both present treatment options for CaP |

DSI DVD designed for general audience | Researcher/Research Staff |

One-time intervention, 30 min/ 3 months post-intervention |

Not reported | Yes |

Recruited from Black Barbershop Health Outreach Program (BBHOP) and other non-BBHOP barbershops. Recruitment was scripted and letters of support and consent for research were obtained from owners. |

VCU’s DSI DVD tailored to African American men using focus group data from African American men to develop the decision tool. The cast in the video are mostly African American |

Barbers Customers |

| Cole, 2017 [55] | Barbershop |

3 arms (PN, MINT, PLUS); cross randomized PN: Patient navigation for CRC screening. 2+ phone calls: 1) education 2) screening readiness assessment & barriers. PN encourage colonoscopy appt. Within 2 weeks. Or FIT if preferred. |

MINT: motivational interviewing and goal setting, 4 sessions PLUS: PN + MINT All: Printed education materials from American Cancer Society and NHLBI |

CHWs/Trained Counselors |

6 months/ 2 weeks and 6 months |

Not reported | Not reported |

Barbershops were identified by study staff from densely populated African American neighborhoods. Participants (customers and local residents) recruited during screening event at barbershop. |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Victor, 2018 [44] | Barbershop |

Barbers measured BP and encouraged follow up with pharmacist Pharmacists met regularly with participants in barbershops, prescribed meds, measured BP, encouraged lifestyle changes, and monitored plasma electrolyte levels Pharmacists followed up with participants’ physician (via progress notes) Pharmacists interviewed participants to generate peer-experience stories (posted on shop walls), reviewed blood-pressure trends, and gave participants $25 per pharmacist visit to offset the costs of generic drugs and transportation to pharmacies. 2 BP screening results with follow up recommendations and identification cards, follow up calls at 3mos, culturally specific health sessions, and vouchers for haircuts |

Active control approach (in which barbers encouraged lifestyle modification and doctor appointment) | Medical Professionals-Pharmacists |

6 months/ Baseline and 6 months |

Peer learning | Not reported | Not reported | No description | Customers |

| Victor, 2019 [45] | Barbershop |

Barbers measured BP and encouraged follow up with pharmacist Pharmacists met regularly with participants in barbershops, prescribed meds, measured BP, encouraged lifestyle changes, and monitored plasma electrolyte levels Pharmacists followed up with participants’ physician (via progress notes) Pharmacists interviewed participants to generate peer-experience stories (posted on shop walls), reviewed BP trends, and gave participants $25 per pharmacist visit to offset the costs of generic drugs and transportation to pharmacies. 2 BP screening results with follow up recommendations and identification cards, follow up calls at 3mos and 9mos, culturally specific health sessions, and vouchers for haircuts |

Instruction about BP and lifestyle modification | Medical professionals-Pharmacists |

12 months/ baseline, 6 months, and 12 months |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | No description | Customers |

BP Blood Pressure, CaP Prostate Cancer, CRC Colorectal Cancer, PA Physical Activity, PCS Prostate Cancer Screening, BC Breast Cancer, CBE Clinical Breast Examination, AHA American Heart Association, HTN Hypertension, VCU Virginia Commonwealth University, DSI Decision Support Instrument, FIMDM Informed Medical Decisions Foundation, CHW Community Health Worker

Barbershop/hair salon recruitment strategies were described for most of the studies. Five of the studies employed community agencies or existing community partnerships to recruit sites [29, 30, 50, 51, 53]. Three studies targeted certain geographical areas [27, 55, 56]. For two studies, hair stylists were assessed for fit with the mission of the project [20, 30]. And one study reported specific criteria for selection of barbershops [56]. Aside from using the barbershop or hair salon as the primary site for interventions, other culturally adapted strategies used were tailoring materials (print/media) for African Americans and in some cases specifically by gender. Materials were either developed or tested by the target audience prior to use in the studies. Other tactics were ensuring interventionists and/or data collectors were African American. One study incorporated ancestral storytelling, a traditional African communication model, as a mechanism for the hair stylists to deliver the intervention message to their clients and subsequently to their clients’ family and friends [30]. The majority of studies provided incentives to barbers/stylists and/or customers. Intervention content focused on the following topics: cancer (screening, prevention, treatment, medical provider engagement, access, risk factors, general knowledge), cardiovascular disease (blood pressure (BP)/hypertension (HTN) treatment, medical provider engagement, access), diabetes (screening, medical provider engagement, access, risk factors, general knowledge), obesity (physical activity, diet, water consumption), skill building, and self-efficacy to engage in the intended health behavior.

For interventions delivered by barbers or hair stylists (n = 8), details about intervention training and fidelity strategies are provided in Table 3. Trainings were in-person and facilitated by the researcher/research staff and when appropriate medical or content professionals. Written materials (handbooks, brochures, scripts, etc.) were used to supplement trainings as well as ongoing/refresher trainings. Intervention fidelity strategies included on-site monitoring by research staff or a community research partner, regular quality assurance review of the data being collected, and researcher accessibility to the barbers/stylists for continued support. One study did not monitor fidelity throughout the intervention, but did post-study surveys and interviews with study participants to evaluate barber intervention delivery [56].

Table 3.

Barber/Stylist Led Interventions

| Author, Year | Interventionist/Setting | Intervention Training | Intervention Fidelity Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbers/Barbershop | Not reported | Research staff regularly checked the validity of the encounter form data against data stored in the electronic monitors and intermittently observed customer flow to validate the barbers’ counts of adult and child business. |

| Wilson, 2008 [27] | Hair Stylists/Hair Salon |

Stylists were trained to conduct tailored and culturally sensitive counseling that would encourage clients to engage in breast health behaviors 2, two-hour workshops, a reference handbook, and ongoing support and technical assistance by research staff. Stylist training was implemented in waves, based on planned initiation of intervention activities in that salon |

Program staff made frequent visits to salons to support stylists in their promotion of message delivery throughout the time during which the program was administered. |

| Holt, 2010 [49] | Barbers/Barbershop |

Barbers trained by community advisory panel. One day of training education training modules and barbers given strategies for helping their clients make informed decisions about screening |

Did not collect/not report. |

| Johnson, 2010 [20] | Hair Stylists/Hair Salon |

Stylists were trained by research team. Motivational sessions using a script as a guide with practice and feedback from research team member. |

Weekly check-ins. |

| Luque, 2011 [50] | Barbers/Barbershop | 10 contact hours of training (didactic, interactive group, and team building) on administering materials by research team, health agency partners, and local urologist at agency’s facilities and in barbershops. | Health agency partner monitored barbers via shop visits, attended project meetings, and facilitated focus group work with barbers for post-intervention evaluation. |

| Sadler, 2011 [29] | Hair Stylists/Hair Salon |

Cosmetologists received ~ 4 h of 1-on-1 training with the Principal Investigator and an additional 4 h of reading materials that reviewed and summarized the Principal Investigator’s training. The reading materials resources: National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, and Susan G. Komen-for-the-Cure Foundation. Cosmetologists also received individual training from an African American ancestral storyteller to enhance their ability to pass along their health promotion messages orally. Every two weeks, the cosmetologists were given hands-on training materials and shown ways the materials could be used to facilitate discussions with their clients to keep the screening message updated with fresh information |

Principal Investigator made unannounced visits to salons every 2 weeks during the first 3 months and then monthly thereafter to restock and bring new materials (for consistency), offer training, and answer questions. Principal Investigator was accessible to cosmetologists at all times. |

| Victor, 2011 [27] | Barbers/Barbershop | Not reported | Participant follow up survey and interview data on intervention delivery by barbers. |

| Sadler, 2014 [30] | Hair Stylists/Hair Salon |

IRB consent training. Stylists received 1-on-1 training with the Principal Investigator and reading materials. Stylists also received individual training from an African American ancestral storyteller to enhance their ability to pass along their health promotion messages orally. The stylists were given ongoing training from the Principal Investigator and participated in biannual luncheon trainings. Screening message updated with fresh information. |

Principal Investigator and research team made unannounced visits to salons. Principal Investigator was accessible via cell phone to stylists at all times. |

Outcomes

Primary, secondary, and feasibility outcomes data are presented in Table 4. There was significant heterogeneity in outcomes with most primary outcomes being behavioral and four studies reporting clinical outcomes related to BP/ HTN [21, 44, 45, 56]. Behavioral outcomes included clinic-based screening (completion/intent), home-based screening (self-exam), provider follow up (treatment, general conversation), physical activity (quantity), and diet (servings of fruit/vegetables and water consumption). Six studies reported significant between-group differences [20, 21, 44, 45, 55, 56] while two reported significant with-in group differences [52, 53]. All studies that reported changes in HTN treatment had significant findings. Two articles where each intervention served as the comparison for the other, reported significant outcomes related to cancer screening for both groups, but non-significant results for the diabetes screening (between-group and intervention). The interventions were identical in every aspect except content (specific to disease state) [29, 30].

Table 4.

Outcomes

| Author, Year | Setting | Primary Outcomes | Primary Results | Secondary Outcomes | Secondary Results (Significant) | Feasibility Outcomes | Feasibility Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbershop |

Change in BP Changes in HTN Treatment rate (percentage of hypertensive subjects receiving prescription BP medication) HTN control rate |

I: BP fell 16 +/− 3/9 +/− 2 mmHg (systolic: 149.1 +/− 2.2 to 133.4 +/− 2.2 mmHg; diastolic: 87.4 +/− 2.6to 78.82.6 mmHg) C: Unchanged (systolic: 146.4 +/− 2.4 to 146.7 +/− 2.4 mmHg; diastolic: 87.9 +/− 2.2 to 88.0 +/− 2.2 mmHg) Intervention effectremained significant (P < 0.0001) after adjustment for age and body mass index I: HTN treatment increased from 47 to 92% (P < 0.001) C: Unchanged I: HTN control increased from 19 to 58% (P < 0.001) C: Unchanged |

Implementation | high percentage of haircuts accompanied by a BP recording, as well as BP readings interpreted correctly. | ||

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Barbershop | Proportion of haircuts in which the barber recorded a BP | 81% haircuts barber recorded a BP | HTN control rate |

HTN control rate increased progressively with increasing levels of intervention exposure: 20+/− 10.7% to 51+/− 9% (p = 0.01) Association between intervention exposure and HTN control remained significant after controlling for insurance status (p = 0.01) |

Implementation |

high percentage of haircuts accompanied by a BP recording BP readings interpreted correctly. Barbers correctly staged 92% of BPs |

| Wilson, 2008 [27] | Hair Salon |

Self-breast exam (BSE) completion Clinical breast exam (CBE) completion CBE intention (12 months) Mammogram completion Mammogram intention (12 months) |

BSE completion: AOR 1.60 (95% CI: 1.2–2.13) CBE completion: AOR 1.20 (95% CI: 0.94–1.52) CBE intention: AOR 1.87 (95% CI: 1.11–3.13) Mammogram completion: AOR 1.21 (95% CI: 0.84–1.76) Mammogram intention: AOR 1.34 (95% CI: 0.9–1.2) |

Implementation- degree of execution | 37% intervention vs. 10% control reported exposure to breast health messages | ||

| Holt, 2010 [51] | Barbershop |

CaP screening/intent to screen (PSA/DRE) CRC screening/intent to screen (FOBT/FS/CS) |

Possible increases in self-reported PSA test and prep for PSA and DRE. I: constantly greater increase in awareness, screening, and prep for FS |

CaP knowledge CRC knowledge CRC screening perceived barriers and benefits |

Results not significant | Not reported | Not reported |

| Johnson, 2010 [20] | Hair Salon |

Increase in fruit and vegetable consumption Increase in physical activity Increase in water consumption |

Fruit and vegetable intake increased from pre-posttest for the treatment group No increase in physical activity No increase in water consumption |

Not reported | Not reported | ||

| Luque, 2011 [53] | Barbershop |

Likelihood of discussing CaP with healthcare provider (4-point Likert scale (very unlikely to very likely)) CaP knowledge (5 pt. Likert scale (low to high)) |

Somewhat likely to very likely Increased from 75 to 85% p < .001 78% reported increase in knowledge |

Feelings of worry about CaP (4 pt. Likert not worried to very worried) Projected PCS modality intention (PSA, DRE, or both) |

Somewhat worried to very worried increased from 35 to 45%. p < .001 85%- Both (PSA & DRE) |

Satisfaction with the intervention Intention to continue the intervention Expansion and implementation |

Participants reported that the materials were easy to understand, had an attractive color scheme, and featured familiar faces printed on the materials. All barbershop clients surveyed reported positively on the contents of the brochure and poster 53% had discussed CaP at least two times with their barber in the last month |

| Sadler, 2011 [29] | Hair Salon | Adherence to Mammography screening guidelines |

ITT between groups at follow up not significant ITT for mammography completers in both groups significantly (p < .05) higher at follow up. Adjusting for age (40+) as covariate yielded adherence to screening OR 2.0 (95% CI: 1.03–3.85) times higher for I vs C |

Clinical breast exam adherence Participants’ awareness and perceptions of their vulnerability for breast cancer |

ITT for perception of seriousness of BC as health threat reduced significantly (p < .05) in both groups, but greater reduction in diabetes arm. OR of listing BC as threat 1.8 times higher in BC arm (95% CI: 1.0–3.1). |

Practicality Implementation- degree of execution |

57% of the women reported that health education materials were displayed in their salon 57% participants reported that the cosmetologists in their salon were offering health information to their clients 80% of the women felt cosmetologists could effectively carry out intervention |

| Victor, 2011 [49, 56] | Barbershop |

Change in HTN control rates (BP measurements and prescription labels) Patron-physician follow up interaction (signed referral card) |

Greater HTN control in I vs C Intervention effect: Absolute group difference- 8.8% (95% CI: 0.8–16.9; Unadjusted: p = .04 Adjusted p = .03) Intervention effect: ITT- 7.8% (95% CI: 0.4–15.3; p = .04) |

Barbershop-level changes in HTN treatment rates HTN awareness BP levels |

Results not significant |

Satisfaction with the intervention Intention to continue the intervention Practicality Implementation and Penetration |

83% patrons heard a model story during every one or half their haircuts from barber 77% patrons received BP measurement from barber 51% patrons with elevated BP received counseling/physician referral from barber 98% patrons and all 29 barbers would like the intervention to continue Cost analysis- Cost effectiveness- cost-neutral for health care system would be $50/patron |

| Odedina, 2014 [52] | Barbershop |

CaP screening CaP knowledge Decisional conflict |

CaP Screening intention: 12.78 (2.48) to 13.37 (2.13) p = .0001 CaP knowledge: 63.60 (22.20) to 74.00 (16.80) p = 0.0021 |

Intervention effects | Completion of PN Intervention was significantly associated with study completion and CRC screening |

Satisfaction with the intervention Limited Efficacy |

> 90% of the participants indicated that they were satisfied with the video The mean satisfaction rating was 13.67 on a scale ranging from 3 to 15, indicating a highly satisfactory rating for the video > 75% of the participants indicated that the video: 1) was useful, 2) was understood, 3) not embarrassing, 4) was not too long, 5) not difficult, 6) was relevant, 7) got their attention, 8) has potential to increase CaP knowledge for African American men, and 9) was credible |

| Sadler, 2014 [30] | Hair Salon | Self-reported diabetes screening test in the past year, annual physical exam, and annual eye exam | There were no significant differences in rates of diabetes screening, routine annual screening, and eye exams from baseline to follow-up and between the two arms at follow-up | Knowledge and attitudes about diabetes | Both groups increased significantly from baseline in their overall diabetes knowledge: diabetes arm (M = 4.47; SD = 1.67) and breast cancer arm (M = 4.61; SD = 1.54), P < 0.05 |

Practicality Limited Efficacy Implementation- degree of execution |

75% reported attending salon where health education was being offered. 65% reported cosmetologist made health info available 41% shared info w with family and friends 92% feel cosmetologist could effectively deliver diabetes information |

| Frencher, 2016 [50] | Barbershop | CaP screening via PSA test | n = 58 completed PSA testing (48%) | CaP knowledge and intention |

Changes in knowledge and intention- all significant Intention to screen- increased from 57 to 73% Overall- no between group differences |

Not reported | Not reported |

| Cole, 2017 [55] | Barbershop | CRC screening completion (self-report) |

ITT; Mixed-effects regression analysis PN: 17.5% completion; MINT: 8.4%; PLUS: 17.8% PN: AOR = 2.28; 95% CI = 1.38, 4.34; PLUS: AOR = 2.44; 95% CI = 1.38, 4.34 2xs more likely for CRC screening completion (PN and PLUS) intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.039 |

Not reported | Not reported | ||

| Victor, 2018 [44] | Barbershop | Changes/reduction in systolic blood pressure |

I: 27.0 mmHg reduction in SBP C: 9.3 mmHg Mean reduction in SBP 21.6 mmHg > for I than C (95% CI: 14.7, 28.4); p < .001 ITT Intervention effect: 21.0 mmHg > for I than C (95% CI: 14.0, 28.0); p < .001 |

Changes in DBP Rates of meeting BP goals Numbers of hypertensive meds Adverse drug reactions Self-rated health Patient engagement |

Mean reduction in DBP 14.9 mmHg > in I vs C (95% CI, 10.3 to 19.6; P < 0.001) I: higher % of meeting BP goals I: Increases in use of antihypertensive meds: 55–100%; C: 53–63% (p < .001) |

Limited Efficacy Implementation- degree of execution |

7 in-person pharmacist visits and 4 follow up calls per participant 6 calls/messages to pharmacist per participant 4 BP Checks per participant by barber 4 health lessons per participant by barber |

| Victor, 2019 [45] | Barbershop | Change in SBP |

I: mean reduction = 28.6 mmHg C: mean reduction = 7.2 mmHg Mean SBP reduction 20.8 mmHg > I vs C (95% CI: 13.9, 27.7; p < 0.0001) ITT intervention effect: 20.6 mmHg reduction (95% CI: 13.8, 27.3; p < 0.0001) |

Changes in DBP Rates of meeting BP goals Numbers of hypertensive meds Adverse drug reactions Self-rated health Patient engagement |

Mean DBP reduction 14.5 mmHg > I vs C (95% CI, 9.5–19.5 mmHg; P < 0.0001) I: higher % of meeting BP goals (68% vs 11%; p = 0.0177) I: Increase in use of antihypertensive meds: 57 to 100% C: 53 to 65% No treatment-related adverse events/deaths I: Greater increase in self-rated health and patient engagement scores |

Limited Efficacy Implementation- degree of execution |

11 in-person pharmacist visits (0-6 months = 4;7-12 months = 4) 4 BP checks per participant by barber 4 health lessons per participant by barber |

BP Blood Pressure, SBP Systolic Blood Pressure, DBP Diastolic Blood Pressure, I Intervention, C Control, CaP Prostate Cancer, CRC Colorectal Cancer, PA Physical Activity, PCS Prostate Cancer Screening, PSA Prostate Specific Antigen, DRE Digital Rectal Examination, FOBT Fecal Occult Blood Test, FS Flexible Sigmoidoscopy, CS Colonoscopy, BC Breast Cancer, CBE Clinical Breast Examination, BSE Breast Self-Examination, HTN Hypertension, ITT Intention to Treat

Feasibility outcomes included as an exploratory focus for this review were not always explicitly stated, but assessed the following areas: acceptability (satisfaction, intent to continue use), practicality (quality of implementation, effects on target audience, ability to carry out, cost analysis), integration, limited efficacy (effect size, intended effects on intermediate variables), and implementation (degree of execution, success or failure of execution). Implementation was the most assessed (n = 7) followed by acceptability (n = 5), practicality (n = 3), and limited efficacy (n = 3). Overall, studies reported favorable feasibility outcomes noting barbers/stylists’ ability to deliver, barber/stylists’ degree of executing the interventions, and clients’ satisfaction with interventions. In one study, 98% of participants and all of the barbers expressed a desire to continue with the intervention [56]. One study performed a cost-analysis for a barber delivered hypertension intervention. In the cost-effectiveness model, the intervention was cost-neutral with the intervention costing ~$50 per barbershop patron [56].

Quality of evidence

Global evidence quality ratings for each study appear in Table 5. Guided by the EPHPP evaluation process, studies were rated on the following six components: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals/dropouts. The global rating for each study was determined based on the total number of component “weak” ratings. One study was rated as “strong,” [56] two rated as “moderate,” [44, 45] and eleven rated as “weak.” [20, 21, 27, 29, 30, 50–53, 55] Many of the studies that had a global rating of “weak” had non-RCT study designs resulting in a “moderate” or “weak” study design rating and components that did not apply/could not be rated accordingly. Because most participants were self-referred, many studies rated “weak” on selection bias. Oftentimes, studies did not report on blinding or on validation/reliability of data collection instruments and therefore received component ratings of “weak.” Most studies controlled for confounders during analysis yielding “strong” component ratings.

Table 5.

Quality of Evidence

| Author, Year | Study Design | EPHPP Global Quality Assessment Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Non-Randomized Feasibility | Weak |

| Hess, 2007 [21] | Non-Randomized Feasibility | Weak |

| Wilson, 2008 [27] | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Weak |

| Holt, 2010 [51] | 2 group Pretest-Posttest | Weak |

| Johnson, 2010 [20] | 2 group Pretest-Posttest | Weak |

| Luque, 2011 [53] | 1 group Posttest only | Weak |

| Sadler, 2011 [29] | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Weak |

| Victor, 2011 [49, 56] | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Strong |

| Odedina, 2014 [52] | 1 group Pretest-Posttest | Weak |

| Sadler, 2014 [30] | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Weak |

| Frencher, 2016 [50] | 2 group Pretest-Posttest | Weak |

| Cole, 2017 [55] | Randomized Control Trial | Weak |

| Victor, 2018 [44] | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Moderate |

| Victor, 2019 [45] | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Moderate |

Discussion

With the disproportionate rates of obesity-related chronic diseases in the African American community, there is an imperative need to better elucidate strategies for engagement in health promotion interventions. Due to historically unethical medical and research practices in the U.S., African Americans have a longstanding history of mistrust of the medical and research community resulting in low participation and engagement, furthering the gap in health [8, 57, 58]. To remedy this, the use of culturally “safe” spaces such as churches, barbershops, and hair salons for recruitment and engagement of African Americans into research studies and lifestyle/behavioral interventions have become increasingly popular [59–61]. To this end, designing interventions to be delivered in trusted, culturally significant settings are advantageous. Barbershops and hair salons are highly accessed, cultural staples in the African American community perfectly situated to tackle the health disparities that plague this community.

This is the first review to synthesize the effectiveness and feasibility of obesity-related chronic disease interventions targeted for African Americans delivered in barbershops and hair salons. Eight of the fourteen studies included in this review reported significant results for clinical and/or behavioral outcomes suggesting that interventions delivered in barbershops and hair salons may be effective for reducing risk factors for or improving health outcomes of obesity-related chronic conditions in African Americans. Of these studies, half used an RCT design, the most rigorous methodology for establishing effectiveness. However, only one of these studies received a “strong” global quality assessment rating, while two received a rating of “moderate” and one received a rating of “weak” due to deficiencies in blinding and selection bias, data collection methods and reporting of withdrawals/dropouts, respectively. This coupled with the variability of duration for interventions point to the need for more efficacious research with considerations for the nuances of community-based study designs.

Among the research with significant results, the outcomes are split evenly between clinical and behavioral. Clinical interventions focused on changes in blood pressure and HTN management while behavioral interventions that can support clinical outcomes included cancer (prostate and colorectal) screening. Furthermore, half of these interventions were delivered or supported by the barbers/hair stylists. Considered together, these details suggest that barbershop/hair salon-based interventions can have a valuable direct or indirect impact in health promotion research. Most studies evaluated feasibility elements, but those were not among primary outcomes nor did any studies compare intervention components such as setting (i.e. barbershop versus church/clinic/other community site) or interventionist (i.e. barber versus clinician/community health worker/researcher). One study where the researcher was the interventionist was replicated by the study team using the barber as the interventionist, but outcomes reported differed [21]. Future research would also benefit from examining the association of racial and gender congruence between the barber/stylist interventionist and clients and the desired outcomes. More research is needed to disentangle which components of the interventions are influencing outcomes.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this systematic review. The heterogeneity of the studies (study designs, sample sizes, intervention characteristics, and outcomes) made it difficult to compare the effectiveness of intervention strategies. This was due in part to the inclusion of multiple disease states, however, there were small number of studies identified through a comprehensive search strategy. However, limiting the search to one disease state or outcome would have further restricted the number of relevant articles for inclusion. Smaller, non-RCT, short-term studies of moderate and weak quality did not support the evidence for or against the efficacy of barbershop/salon-based interventions. Self-reported data could have overpredicted effectiveness of interventions. Another limitation is that seven of the studies were conducted by the same three lead authors (three by one, two by one, and two by one) indicating potential publication bias. Finally, generalizability of the studies’ findings is questionable given most studies were conducted in large, urban cities with participants of higher socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

Health promotion interventions delivered in barbershops and hair salons for African Americans appear to be modestly effective for reducing risk and improving health outcomes for obesity-related chronic diseases. Overall, the literature in this area is limited and varies in foci. The extent to which the barber/stylist is utilized warrants further investigation. Objective measurements could enhance results. While barbershops have been shown to be effective locations for recruitment of African American men, who have been the target audience for such interventions due to the difficulty with recruiting and engagement in health promotion interventions, research in hair salons with African American women deserves more attention. Moreover, interventions that address complex, layered behavior change associated with obesity and diabetes are needed while balancing the appropriateness of desired outcomes (behavioral versus clinical). While all community-based research can be involved and complicated, it can be gleaned from this literature that barbershops/hair salon-based interventions are feasible. The barbershop/hair salon and to a further extent, the barber and hair stylist, can serve to support the implementation of existing evidence-based interventions, possibly in partnership with the health care system, to address obesity and chronic disease health inequities for African Americans.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2. Data extraction form.

Additional file 3. Quality assessment form.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues for their continuous support.

Abbreviations

- BP

Blood pressure

- CBPR

Community-based participatory research

- EPHPP

Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool

- HTN

Hypertension

- NHW

Non-Hispanic whites

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- RCT

Randomized control trial

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- SCT

Social cognitive theory

- SES

Socioeconomic status

- U.S.

United States

Authors’ contributions

KP designed and drafted the review manuscript, registered the review, coordinated the review process, and is the guarantor of the systematic review. KP, JM, JH, DM, CT, and DG contributed to the review’s initial conception. KP, JM, and DG developed the search strategies and performed the search. KP, PR, and FM reviewed studies for inclusion, and extracted and analyzed data. JH, DM, CT, and DG revised and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported with funds from the University of Arizona Health Sciences Center for Border Health Disparities through a paid subscription to Covidence for data collection.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kelly N. B. Palmer, Email: kpalmer1@arizona.edu

Patrick S. Rivers, privers@email.arizona.edu

Forest L. Melton, fmelton@email.arizona.edu

D. Jean McClelland, jmcc@email.arizona.edu.

Jennifer Hatcher, jhatcher@email.arizona.edu.

David G. Marrero, dgmarrero@email.arizona.edu

Cynthia A. Thomson, cthomson@email.arizona.edu

David O. Garcia, davidogarcia@email.arizona.edu

References

- 1.United States Census Bureau . QuickFacts- Population estimates- Race and Hispanic Origin [Table] 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: racial disparities in age-specific mortality among blacks or African Americans—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444–456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no288. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackwell D, Lucas JW, Clarke T. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Atlanta: Census Bureau for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistic; 2014.

- 5.Ward EM, Sherman RL, Henley SJ, Jemal A, Siegel DA, Feuer EJ, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of Cancer, featuring Cancer in men and women age 20–49 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(12):1279–1297. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(1_suppl2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noonan AS, Velasco-Mondragon HE, Wagner FA. Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: an overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Rev. 2016;37(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s40985-016-0025-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public health reports. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branson RD, Davis K, Jr, Butler KL. African Americans’ participation in clinical research: importance, barriers, and solutions. Am J Surg. 2007;193(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown Speights JS, Nowakowski AC, De Leon J, Mitchell MM, Simpson I. Engaging African American women in research: an approach to eliminate health disparities in the African American community. Fam Pract. 2017;34(3):322–329. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchholz SW, Wilbur J, Schoeny ME, Fogg L, Ingram DM, Miller A, Braun L. Retention of African American women in a lifestyle physical activity program. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(3):369–385. doi: 10.1177/0193945915609902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitt-Glover MC, Borden SL, Alexander DS, Kennedy BM, Goldmon MV. Recruiting African American churches to participate in research: the learning and developing individual exercise skills for a better life study. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(2):297–306. doi: 10.1177/1524839915623499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lancaster KJ, Carter-Edwards L, Grilo S, Shen C, Schoenthaler AM. Obesity interventions in African American faith-based organizations: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15(Suppl 4):159–176. doi: 10.1111/obr.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KH-c, Linnan L, Kramish Campbell M, Brooks C, Koenig HG, Wiesen C. The WORD (wholeness, oneness, righteousness, deliverance): a faith-based weight-loss program utilizing a community-based participatory research approach. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(5):634–650. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumanyika S, Taylor WC, Grier SA, Lassiter V, Lancaster KJ, Morssink CB, Renzaho AMN. Community energy balance: a framework for contextualizing cultural influences on high risk of obesity in ethnic minority populations. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant CG, Davis JL, Rivers BM, Rivera-Colón V, Ramos R, Antolino P, Harris E, Green BL. The men’s health forum: an initiative to address health disparities in the community. J Community Health. 2012;37(4):773–780. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markens S, Fox SA, Taub B, Gilbert ML. Role of black churches in health promotion programs: lessons from the Los Angeles mammography promotion in churches program. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):805–810. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linnan L, Thomas S, D’Angelo H, Ferguson YO. African American barbershops and beauty salons. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linnan LA, D'Angelo H, Harrington CB. A literature synthesis of health promotion research in salons and barbershops. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson LT, Ralston PA, Jones E. Beauty salon health intervention increases fruit and vegetable consumption in African-American women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(6):941–945. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess PL, Reingold JS, Jones J, Fellman MA, Knowles P, Ravenell JE, Kim S, Raju J, Ruger E, Clark S, Okoro C, Ogunji O, Knowles P, Leonard D, Wilson RP, Haley RW, Ferdinand KC, Freeman A, Victor RG. Barbershops as hypertension detection, referral, and follow-up centers for black men. Hypertension. 2007;49(5):1040–1046. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis C, Darby K, Moore M, Cadet T, Brown G. Breast care screening for underserved African American women: community-based participatory approach. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2017;35(1):90–105. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2016.1217965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floyd TD, DuHamel KN, Rao J, Shuk E, Jandorf L. Acceptability of a salon-based intervention to promote colonoscopy screening among African American women. Health Educ Behav. 2017;44(5):791–804. doi: 10.1177/1090198117726571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forte DA. Community-based breast cancer intervention program for older African American women in beauty salons. Public Health Rep (Washington, DC : 1974) 1995;110(2):179–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luque J, Roy S, Tarasenko Y, Ross L, Johnson J, Gwede C, et al. Feasibility study of engaging barbershops for prostate Cancer education in rural African-American communities. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(4):623–628. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0739-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luque J, Ross L, Gwede C. Qualitative systematic review of barber-administered health education, promotion, screening and outreach programs in African-American communities. J Community Health. 2014;39(1):181–190. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson TE, Fraser-White M, Feldman J, Homel P, Wright S, King G, Coll B, Banks S, Davis-King D, Price M, Browne R. Hair salon stylists as breast cancer prevention lay health advisors for African American and afro-Caribbean women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(1):216–226. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Cohn JA, White M, Weldon RN, Wu P. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and screening behaviors among African American women: the black cosmetologists promoting health program. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):57–58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Wu P, Alisangco J, Castañeda SF, Kelly C. A cluster randomized controlled trial to increase breast cancer screening among African American women: the black cosmetologists promoting health program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):735–745. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30413-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadler GR, Ko CM, Wu P, Ngai P. Lessons learned from the black cosmetologists promoting health program: a randomized controlled trial testing a diabetes education program. J Commun Healthcare. 2014;7(2):117–127. doi: 10.1179/1753807614Y.0000000050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadler GR, Thomas AG, Dhanjal SK, Gebrekristos B, Wright FA. Breast cancer screening adherence in African-American women: black cosmetologists promoting health. Cancer Interdisciplinary Int J Am Cancer Society. 1998;83(S8):1836–1839. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981015)83:8+<1836::AID-CNCR34>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadler GR, Thomas AG, Gebrekristos B, Dhanjal SK, Mugo J. Black cosmetologists promoting health program: pilot study outcomes. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15(1):33–37. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Browne RC. Most black women have a regular source of hair care--but not medical care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(10):1652–1653. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Versey HS. Centering perspectives on black women, hair politics, and physical activity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(5):810–815. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smalls BL, Walker RJ, Bonilha HS, Campbell JA, Egede LE. Community interventions to improve glycemic control in African Americans with type 2 diabetes: a systemic review. Glob J Health Sci. 2015;7(5):171–182. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v7n5p171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzgibbon ML, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Porter JS, Martin IK, Odoms-Young A, Sharp LK. Weight loss and African–American women: a systematic review of the behavioural weight loss intervention literature. Obes Rev. 2012;13(3):193–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bland V, Sharma M. Physical activity interventions in African American women: a systematic review. Health Promotion Perspect. 2017;7(2):52–59. doi: 10.15171/hpp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barr-Anderson DJ, Adams-Wynn AW, DiSantis KI, Kumanyika S. Family-focused physical activity, diet and obesity interventions in African-American girls: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14(1):29–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lofton S, Julion WA, McNaughton DB, Bergren MD, Keim KS. A systematic review of literature on culturally adapted obesity prevention interventions for African American youth. J Sch Nurs. 2016;32(1):32–46. doi: 10.1177/1059840515605508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UyBico SJ, Pavel S, Gross CP. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: a systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ndumele CD, Ableman G, Russell BE, Gurrola E, Hicks LS. Publication of recruitment methods in focus group research of minority populations with chronic disease: a systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):5–23. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer K, Rivers P, Melton F, McClelland J, Hatcher J, Marrero DG, Thomson C, Garcia DO. Protocol for a systematic review of health promotion interventions for African Americans delivered in US barbershops and hair salons. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e035940. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx-Drew D, Moy N, Reid AE, Elashoff RM. A cluster-randomized trial of blood-pressure reduction in black barbershops. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):1291–1301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Victor RG, Blyler CA, Li N, Lynch K, Moy NB, Rashid M, Chang LC, Handler J, Brettler J, Rader F, Elashoff RM. Sustainability of blood pressure reduction in black barbershops. Circulation. 2019;139(1):10–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Cummings GG. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane collaboration risk of Bias tool and the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool: methodological research. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jackson N, Waters E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(4):367–374. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Victor RG, Ravenell JE, Freeman A, Leonard D, Bhat DG, Shafiq M, Knowles P, Storm JS, Adhikari E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson PG, Pletcher MJ, Hannan P, Haley RW. Effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men: the BARBER-1 study: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):342–350. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frencher SK, Jr, Sharma AK, Teklehaimanot S, Wadzani D, Ike IE, Hart A, Norris K. PEP talk: prostate education program, “cutting through the uncertainty of prostate Cancer for black men using decision support instruments in barbershops”. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(3):506–513. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0871-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holt CL. Cancer awareness in alternative settings: lessons learned and evaluation of the barbershop Men's health project. J Health Disparities Res Pract. 2010;4(2):100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Odedina F, Oluwayemisi AO, Pressey S, Gaddy S, Egensteiner E, Ojewale EO, et al. Development and assessment of an evidence-based prostate cancer intervention programme for black men: the W.O.R.D. on prostate cancer video. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8(447–473):1–15. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2014.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luque JS, Rivers BM, Gwede CK, Kambon M, Green BL, Meade CD. Barbershop communications on prostate cancer screening using barber health advisers. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5(2):129–139. doi: 10.1177/1557988310365167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]