Abstract

Background:

Advanced practice providers in the outpatient setting play a key role in antibiotic stewardship, yet little is known about how to engage these providers in stewardship activities and what factors influence their antibiotic prescribing practices.

Methods:

We used mixed methods to obtain data on practices and perceptions related to antibiotic prescribing by nurse practitioners (NP) and Veteran patients. We interviewed NPs working in the outpatient setting at one Veterans Affairs facility and conducted focus groups with Veterans. Emerging themes were mapped to the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety framework. We examined NP antibiotic prescribing data from 2017 to 2019.

Results:

We interviewed NPs and conducted Veteran focus groups. Nurse practitioners reported satisfaction with resources, including ready access to pharmacists and infectious disease specialists. Building patient trust was reported as essential to prescribing confidence level. Veterans indicated the need to better understand differences between viral and bacterial infections. NP prescribing patterns revealed a decline in antibiotics prescribed for upper respiratory illnesses over a 3-year period.

Conclusion:

Outpatient NPs focus on educating the patient while balancing organizational access challenges. Further research is needed to determine how to include both NPs and patients when implementing outpatient antibiotic stewardship strategies. Further research is also needed to understand factors associated with the decline in nurse practitioner antibiotic prescribing observed in this study.

Published by Elsevier Inc. on behalf of Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc.

Keywords: Advanced practice providers, Antibiotic stewardship, Veterans, Outpatient, Ambulatory

Appropriate prescribing of antibiotics is necessary for addressing antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic prescribing that is not concordant with guidelines can result in overprescribing and can impact patient safety by increasing the risk for Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) and bacterial resistance.1–4 Although efforts are increasing to address appropriate prescribing of antibiotics, the primary focus has been interventions targeting physicians5–10 and little is known about advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners (NPs) prescribing and participation in antibiotic stewardship efforts in the outpatient setting. A recent Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America white paper outlined high-value targets for antibiotic stewardship efforts. One such target was identifying stewardship strategies for primary care, urgent care and emergency departments.11

In the United States, NPs can prescribe medications, including antibiotics, with varying degrees of independence based on individual states’ NP practice authority. In early 2019, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) granted independent prescribing authority of advanced practice nurses (which includes NPs), even in states that require physician oversight. Concurrently, there has been a significant increase in the number of NPs hired by the VA health system to address expanded capacity of primary medical care. Current data indicate an estimated 7,000 NPs working for the VHA alone, with an estimated 2,500 working in primary care. This makes NPs well-positioned as stewards of antibiotics.

Studies focused on NP prescribing have been conducted primarily in pediatric or long-term care settings.12–14 There have been studies comparing other prescribers to physician prescribers. These studies indicate that antibiotics are more frequently prescribed during visits with NPs and physician assistants compared to physician-only visits.15–17 Suda et al also examined trends in antibiotic prescriptions by provider type from 2005 to 2010 and showed that, during this time period, overall prescriptions for broad-spectrum antibiotic agents decreased for physicians and increased for NPs and physician assistants. These data suggest increasing trends in the United States for prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics may be, in part, attributable to prescribers other than physicians.18

Uncovering factors influencing NP decision-making is essential to optimize guideline-concordant antibiotic prescribing. However, patients are also key stakeholders in antibiotic stewardship efforts. Literature indicate that patients recognize antibiotic resistance as a serious public health problem but may not perceive themselves as personally affected by it.19 There is also evidence that patients do not understand when an antibiotic is needed or not needed and can pressure prescribers for an antibiotic prescription.20,21 Further investigation is needed to elucidate specifics on how patients could engage as good stewards to improve prescribing practices.

The goal of our study was to identify barriers and facilitators to guideline-concordant prescribing among NP prescribers in a VHA outpatient setting. We also wanted to explore perspectives about perceived roles in antibiotic stewardship efforts—both NPs and patient roles.

METHODS

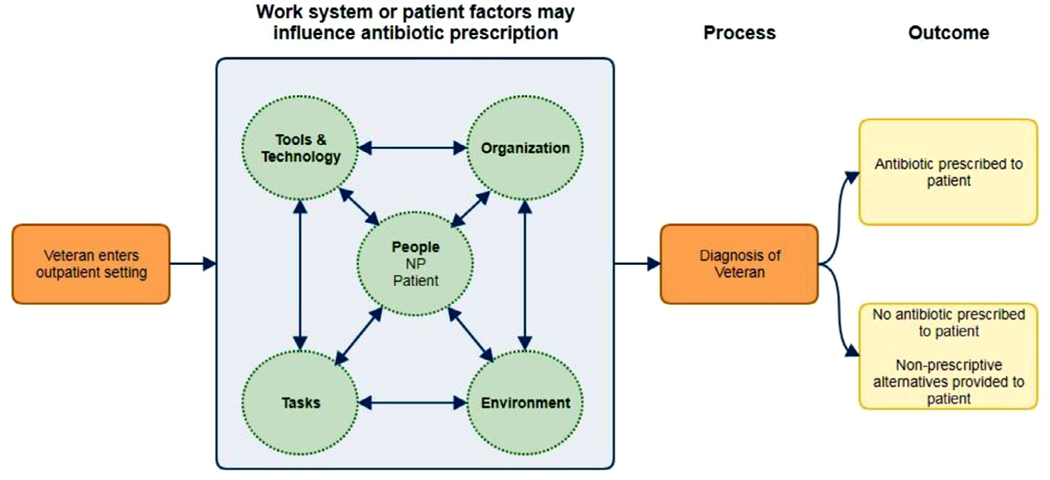

We used a convergent parallel mixed methods design to uncover barriers and facilitators that can guide strategies to improve guideline-concordant prescribing of antibiotics. Data analyses (qualitative and quantitative) occurred separately, and neither analysis depended on the other during the final analysis. Findings were not compared or consolidated until analyses were completed.22–24 As a recent study of methods used to examine NP prescribing indicated the need for a theoretical framework,25 we used a systems approach—the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model (Fig 1)—to examine workflow and organizational factors that hinder or help NPs in making decisions about prescribing antibiotics. In this study, we examined process outcomes related to each aspect of the work system (people—those involved in the process of prescribing; tasks—diagnosing, guideline retrieval, and prescribing; tools—the electronic medical record, guidelines, and testing equipment; organization—the policies related to antibiotic prescribing and leadership aspects of implementing stewardship activities; environment—the physical environment of the VA ambulatory clinics). The SEIPS model emphasizes that any one work system component can affect changes in all other components.26,27

Fig 1.

Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model adapted to this study.

Study population

The primary study population was VA-employed NPs working in an outpatient capacity at one VA medical facility (William S. Middleton VA Hospital, Madison, WI) that includes 6 satellite ambulatory sites known as Community-based Outpatient Clinics (CBOCs). Veterans receiving care at any VA facility made up the study population of patient focus groups. Participation was voluntary for both NPs and Veterans. The institutional review board (IRB) determined this study met criteria for exempt human subjects research.

Qualitative data—NP interviews

We conducted face-to-face semistructured interviews to explore NP decision-making for patients presenting with nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections. We recruited NPs for study participation by presenting our study during a staff meeting. Study fact sheets were distributed during this meeting. The Associate Director of Patient Care Services attended this meeting and endorsed using NP protected time for the interview. We obtained names for all facility-level NPs who work in outpatient settings. An email request with the fact sheet was sent by the primary investigator to all NPs. Once the NP agreed to participate, the lead investigator called or emailed to coordinate a date and time to meet at the outpatient setting or, if an in-person interview was not feasible, a phone call interview was scheduled.

Interviews were conducted at 6 CBOCs located in rural areas of 2 states. At the time of this study (2019), there were 31 NPs working in the 6 CBOCs. We were able to reach 14 NPs (45%) for an in-person interview, with 2 interviews conducted by phone due to NP preference. All NPs were interviewed prior to February 2020—prior to the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown. We used both inductive and deductive methods to analyze interview data. Statements were extracted from transcripts and organized into themes and mapped to SEIPS elements. Interviews were recorded, transcribed by a VA-approved transcriptionist, coded for recurring themes, and mapped to the SEIPS framework (Fig 1). We used a survey conducted with NPs in 2012 as a starting point for developing the interview questions5 and consulted with a local VA infectious disease physicians. Questions were vetted by 2 investigators (KS and KB) and the primary investigator pilot tested the questions with 3 NPs at a rural VA facility not participating in the project. Modifications were made to questions based on the pilot test. The interviews covered topics such as appropriate prescribing, perceptions and ideas about the NP role in antibiotic stewardship, participating in developing an intervention targeting NPs, the VA policy mandating antibiotic stewardship, and barriers and facilitators to concordant prescribing in the outpatient VA setting. We also included questions on level of prescribing confidence, personal prescribing versus other NP prescribing, concern about antibiotic resistance, broad spectrum antibiotics versus using narrow spectrum agents and antibiotic stewardship program elements. We covered the “should you treat” and “how you treat” aspects of prescribing.

Qualitative data—Veteran focus groups

Focus groups were conducted with Veterans to generate multiple perspectives in an interactive group setting. Three focus groups were held between November 9, 2019 and January 9, 2020 (prior to COVID-19 restrictions). Recruitment consisted primarily of word of mouth. Inclusion criteria consisted of any Veteran, with no age or gender restrictions. A skilled focus group leader led all three focus groups (KB), while the primary investigator (MJK) took notes by hand. Focus group questions were generated from a combination of general literature related to patient engagement in antibiotic stewardship and the SEIPS framework. We piloted focus group questions with an existing health care-associated infection patient engagement group, which included Veterans. Order of questions and language were modified based on feedback from this group. At the conclusion of each focus group, the facilitator circulated examples of patient-centered antibiotic stewardship materials available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Focus group participants provided feedback on these materials. Duration of each focus group was approximately 1.5 hours. Veterans were paid $150 for participating to cover time and driving expenses. All 3 focus groups were conducted at the Madison VA facility.

Quantitative data

To assess guideline concordance with antibiotic prescribing, we extracted data over 3 calendar years (2017–2019) on NP prescribing for diagnoses categories (acute unspecified upper respiratory infections) in which, according to guidelines, antibiotics are not indicated. For those Veterans prescribed an antibiotic, we examined 2 diagnoses—acute bronchitis unspecified and acute respiratory infection unspecified for the type of antibiotic prescribed. Current CDC adult treatment recommendations indicate no antibiotics are needed for these 2 diagnoses. We also extracted patient demographic data including distance the Veteran lives from the CBOC (using zip codes). We also examined day of week and time of day of the clinic visit related to Veterans prescribed an antibiotic and those who were not prescribed an antibiotic, separating Monday-Wednesday, from Thursday and Friday visits. Finally, we investigated whether Veterans prescribed an antibiotic for upper respiratory illness had a positive CDI test within 90 days of the antibiotic prescribed.

RESULTS

Fourteen NPs were interviewed; demographic information is included in Table 1. A breakdown of recurring themes categorized by SEIPS elements including barriers and facilitators is depicted in Table 2. NPs appear to be strong advocates for better triage to reduce unnecessary office visits and to decrease unnecessary travel for Veterans and thus, providing access to Veterans needing a higher level of care. The factors most influencing NP comfort level or confidence with prescribing were patient-provider relationships, aversion to risk (potentially avoiding risk) and access to clinical decision support tools, including pharmacists. NPs identify as patient educators and building patient relationships was identified as essential to building trust between patients and providers and this promoted guideline-concordant prescribing by NPs. Time constraints had the least influence on prescribing confidence level, since NPs overwhelming stated that VA provides adequate patient visit time.

Table 1.

Nurse practitioner characteristics (n = 14)

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| 18–39 | 5 (36) |

| 40–59 | 6 (43) |

| >60 | 3 (21) |

| Years since graduate school | |

| <5 | 5 (36) |

| 5–10 | 1 (7) |

| >10 | 8 (57) |

| Years in practice as NP | |

| <5 | 5 (36) |

| 5–10 | 1 (7) |

| >10 | 8 (57) |

| Years in practice at VA(NP or not NP) | |

| <5 | 7 (50) |

| 5–10 | 5 (36) |

| >10 | 2 (14) |

Table 2.

NP interview recurring themes mapped to SEIPS elements

| Recurring theme | SEIPS element | Barrier or facilitator |

|---|---|---|

| VA resources available | Organization | Facilitator |

| Ready access to pharmacists and infectious disease specialists | Organization | Facilitator |

| Lab results delayed if patient visit is late in day | Organization | Barrier |

| Veteran driving distance to outpatient clinic | Organization | Barrier |

| NPs see themselves as educators | People | Facilitator |

| Patient-provider relationships (communication) are critical to prescribing | People | Facilitator |

| Time with patient is adequate | Organization | Facilitator |

| Clinical decision support tools are available | Organization | Facilitator |

A total of 15 Veterans (10 males, 5 females) participated in focus groups. Table 3 outlines recurring themes heard from Veterans with corresponding SEIPS element. These data were integrated with NP interview data to present a comprehensive picture of antibiotic use from the perspectives of both stakeholders—patient and prescriber.

Table 3.

Veteran focus group themes mapped to SEIPS elements

| Recurring theme | SEIPS element/work system or patient factors |

|---|---|

| Knowing the difference between a viral and bacterial infection is important | People Patient knowledge |

| Antibiotics seem to be overprescribed and don’t always work; fear of “superbugs” | Tools and technology Patient knowledge |

| VA experience different than other health care facilities | Organization/work system |

| Pharmacists play a key role in communication with patients about antibiotics | Organization/work system |

| Proper triage can eliminate a trip to the clinic; access issues | Organization; tools and technology/work system |

Examination of prescribing data for 3 years (2017–2019) indicated a sharp downward trend in the proportion of antibiotics prescribed by VA outpatient NPs (Table 4). During these 3 years, acute bronchitis unspecified was diagnosed 94 times with a prescription provided to the patient. In that same time frame, acute upper respiratory infection unspecified was diagnosed 72 times with a prescription provided to the patient. We examined one broad spectrum antibiotic—azithromycin—for these 2 diagnoses. Azithromycin is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic agent.28 For acute bronchitis unspecified, azithromycin was prescribed in 46% (43/94) of visits over a 3-year time period, with a dramatic drop in both 2018 and 2019. However, for acute upper respiratory infection unspecified, azithromycin was prescribed in 28% (20/72) of patient visits but did not drop during the three years (Table 5).

Table 4.

Veterans diagnosed with nonspecific URI by NP (outpatient) versus prescribed an antibiotic (facility-level only)

| Year | No. diagnosed with nonspecific URI | No. prescribed an antibiotic (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 595 | 237 (40%) |

| 2018 | 666 | 68 (10%) |

| 2019 | 609 | 28 (5%) |

Table 5.

Percentage of visits in which azithromycin was prescribed for 2 different diagnoses

| Year | Acute bronchitis unspecified | Acute upper respiratory infection unspecified |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 53% (40/75) | 27% (12/45) |

| 2018 | 14% (2/14) | 30% (5/17) |

| 2019 | 20% (1/5) | 30% (3/10) |

There were no appreciable differences in the average ages of Veterans prescribed an antibiotic and those who were not prescribed an antibiotic (ages ranged from 63 to 67). There were also no appreciable differences in prescribing related to average distance traveled to the outpatient clinic. Distance ranged from 16.61 to 23.89 miles. Examining prescribing related to time of week, we found that NPs did not prescribe differently at the end of the week (Thursday-Friday) versus the beginning of the week (Monday-Wednesday) In fact, for all 3 years, examining prescribing for Thursdays and Fridays, 80% (296/369) of visits ended without an antibiotic being prescribed. Our data pull also indicated no incidences recorded in VA records of a CDI diagnosis during the 3 years for those Veterans prescribed an antibiotic.

DISCUSSION

We uncovered a downward trend in antibiotics being prescribed by NPs during the years 2017–2019. This appears to be contradictory to advanced practice providers’ prescribing trends seen in the private sector.21 This downward trend occurred during the same time period when NPs were given increased prescribing autonomy. An investigation into our local stewardship activities uncovered numerous pharmacy-led stewardship activities during 2018 and 2019. Two examples of these included nurse practitioner education on antibiotic stewardship and antibiotic stewardship reminder in the weekly pharmacy newsletter. Details of these initiatives are provided as Supplementary Appendix A. Although, no definitive correlation can be made, we believe these stewardship activities contributed to local downward trends in antibiotic prescribing and may be replicated at other facilities. This connection between increased outpatient stewardship activities and decreased prescribing of antibiotics is supported by the fact that we found no appreciable difference in antibiotic prescribing related to patient visit day, time of day, age of patient or distance traveled (access) to the clinic.

Including nurses as key stakeholders in antibiotic stewardship has been studied in the past. However, most studies have focused on stewardship opportunities for bedside nurses.29–33 Examining prescribing patterns among outpatient NPs was recently recommended by the nursing profession.34,35 Our study was unique in that we not only examined prescribing patterns, but we also examined NP and Veteran perceptions about antibiotic use and their respective roles in antibiotic stewardship.

First, we found that trust between the NP and patient was viewed as facilitating guideline-concordant prescribing—whether for upper respiratory conditions or other health problems. This important relationship factor between nurses and patients has been previously identified in the context of antibiotic stewardship.36 Second, we learned that organizational factors such as delayed lab results and challenges with triage (patients coming in when not necessary) were viewed as barriers to concordant prescribing. Organizational factors were also outlined in a study on inpatient nurses.31 Nurse practitioners see themselves as patient educators, not just prescribers. Third, there is a need for patient health literacy related to use of antibiotics.37 This harmonizes with current literature related to NPs working in both outpatient and inpatient settings.38–41 Lastly, NPs expressed satisfaction with resources such as clinical decision support tools and access to pharmacists and infectious disease specialists. We found that both NPs and Veterans view pharmacists as an integral part of decision-making related to prescribing of antibiotics. This also harmonizes with current literature related to the increased role of pharmacists in antibiotic stewardship.42–44

Although education efforts by the CDC about antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance has been in place for over 2 decades,45 the need exists to communicate with patients about differences between viral and bacterial infections and why or why not an antibiotic may be needed.37 Veteran patients appeared to understand the consequences of antibiotic overuse—talking about “superbugs”—but did not appear to understand the reason for the overuse. We also learned Veteran patients appreciate time spent with providers and indicated pharmacists as important communicators about the drugs they have been prescribed or are currently using. Veterans also see triage as important to saving driving time—which in rural areas can be significant. Our findings are similar to a recent study on provider perspectives on stewardship in the outpatient setting including the need for further patient education.46

Our findings can be used to address human factors and work system barriers that exist for providers prescribing antibiotics in the outpatient setting—issues which ultimately have clinical implications.47 The marked decline in antibiotic use over a 3-year time period indicates the need for ongoing and consistent stewardship activities targeting advanced practice providers in the outpatient setting.

We did not extract co-morbidities of Veterans presenting with unspecified upper respiratory infections. This could be considered a limitation; however, co-morbidities are not considered rationale for antibiotic prescription for viral respiratory infections. Another limitation is the small number of sites and participants in our study and all NP participants were employed by the same regional facility. However, these preliminary findings related to prescribing practices in conjunction with NP and Veteran perceptions can be used to both scale up and test interventions to increase guideline-concordant prescribing—interventions that are practical and easily integrated into routine care of Veterans seen in the outpatient setting. Stewardship committee activities, as described in Supplement A, can be replicated providing a strategy for those working on outpatient antibiotic stewardship issues.

CONCLUSION

NPs working in the outpatient setting rely not only rely on clinical judgment and reciprocal provider-patient trust, but also on work system tools and technology, such as clinical decision support tools and pharmacists to make prescribing decisions. NPs practice patient-centered care focused on communicating with and educating patients while balancing organizational challenges. This, coupled with increasing numbers of NPs in the outpatient setting, signals the need to include NPs as pivotal players within antibiotic stewardship programs. Further investigation is needed to determine how to increase both NP and patient engagement in outpatient antibiotic stewardship activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the advice and expertise of several key VA stewardship advocates such as VA infectious disease specialists and VA pharmacists. We acknowledge the nursing leadership for allowing NPs protected time for interviews. We acknowledge all NPs and Veterans who participated in this study.

Funding: This work was supported by Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development pilot (1–121-HX002692–01A1).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.01.018.

References

- 1.Fodero KE, Horey AL, Krajewski MP, Ruh CA, Sellick JA Jr., Mergenhagen KA. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on patient safety in veterans prescribed vancomycin. Clin Ther. 2016;38:494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1308–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chitnis AS, Holzbauer SM, Belflower RM, et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013; 173:1359–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dantes R, Mu Y, Hicks LA, et al. Association between outpatient antibiotic prescribing practices and community-associated Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbo L, Smith L, Pereyra M, Wyckoff M, Hooton TM. Nurse practitioners’ attitudes, perceptions, and knowledge about antibiotic stewardship. J Nur Pract. 2012; 8:370–376. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempsey PP, Businger AC, Whaley LE, Gagne JJ, Linder JA. Primary care clinicians’ perceptions about antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchitis: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drekonja DM, Filice GA, Greer N, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in outpatient settings: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36: 142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis by ambulatory care physicians. JAMA. 1997;278:901–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections−success that’s way off the mark: comment on “a cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magin P, Tapley A, Morgan S, et al. Reducing early career general practitioners’ antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections: a pragmatic prospective non-randomised controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2018;35:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris AM, Calderwood MS, Fridkin SK, et al. Research needs in antibiotic stewardship. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40:1334–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goolsby MJ. Antibiotic prescribing habits of nurse practitioners treating pediatric patients: AntiBUGS pediatrics. J Am Acad Nurs Pract. 2007;19:332–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weddle G, Goldman J, Myers A, Newland J. Impact of an educational intervention to improve antibiotic prescribing for nurse practitioners in a pediatric urgent care center. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson BM, Shick S, Carter RR, et al. An online course improves nurses’ awareness of their role as antimicrobial stewards in nursing homes. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez GV, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Cawley JF, Hicks LA. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing among United States nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ference EH, Min JY, Chandra RK, et al. Antibiotic prescribing by physicians versus nurse practitioners for pediatric upper respiratory infections. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:982–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suda KJ, Roberts RM, Hunkler RJ, Taylor TH. Antibiotic prescriptions in the community by type of provider in the United States, 2005–2010. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2016;56:621–626.e621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heid C, Knobloch MJ, Schulz LT, Safdar N. Use of the health belief model to study patient perceptions of antimicrobial stewardship in the acute care setting. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleming-Dutra KE, Mangione-Smith R, Hicks LA. How to prescribe fewer unnecessary antibiotics: talking points that work with patients and their families. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:200–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King LM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Hicks LA. Advances in optimizing the prescription of antibiotics in outpatient settings. BMJ. 2018;363:k3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guetterman TC, Fetters MD, Creswell JW. Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13:554–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Neill BJ, Dwyer T, Reid-Searl K, Parkinson L. Nursing staff intentions towards managing deteriorating health in nursing homes: a convergent parallel mixed methods study using the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:e992–e1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ness V, Price L, Currie K, Reilly J. Influences on independent nurse prescribers’ antimicrobial prescribing behaviour: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:1206–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(suppl 1):i50–i58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caya T, Musuuza J, Yanke E, et al. Using a systems engineering initiative for patient safety to evaluate a hospital-wide daily chlorhexidine bathing intervention. J Nurs Care Qual. 2015;30:337–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1308–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monsees E, Goldman J, Popejoy L. Staff nurses as antimicrobial stewards: an integrative literature review. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monsees E, Goldman J, Vogelsmeier A, Popejoy L. Nurses as antimicrobial stewards: recognition, confidence, and organizational factors across nine hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monsees E, Lee B, Wirtz A, Goldman J. Implementation of a nurse-driven antibiotic engagement tool in 3 hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monsees E, Popejoy L, Jackson MA, Lee B, Goldman J. Integrating staff nurses in antibiotic stewardship: opportunities and barriers. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46: 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monsees EA, Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE, Miller MA, Fabre V. Integrating bedside nurses into antibiotic stewardship: a practical approach. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40:579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards R, Drumright L, Kiernan M, Holmes A. Covering more territory to fight resistance: considering nurses’ role in antimicrobial stewardship. J Infect Prev. 2011;12:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manning ML, Pfeiffer J, Larson EL. Combating antibiotic resistance: the role of nursing in antibiotic stewardship. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:1454–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olans RD, Olans RN, Witt DJ. Good nursing is good antibiotic stewardship. Am J Nurs. 2017;117:58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castro-Sanchez E, Chang PWS, Vila-Candel R, Escobedo AA, Holmes AH. Health literacy and infectious diseases: why does it matter? Int J Infect Dis. 2016;43:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griggs KM, Hrelic DA, Williams N, McEwen-Campbell M, Cypher R. Preterm labor and birth: a clinical review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2020;45:328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoy HM, O’Keefe LC. Practical guidance on the recognition of uncontrolled asthma and its management. J Am Assoc Nurs Pract. 2015;27:466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lareau SC, Hodder R. Teaching inhaler use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Am Acad Nurs Pract. 2012;24:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rance KS. Helping patients attain and maintain asthma control: reviewing the role of the nurse practitioner. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bishop C, Yacoob Z, Knobloch MJ, Safdar N. Community pharmacy interventions to improve antibiotic stewardship and implications for pharmacy education: a narrative overview. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15:627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parente DM, Morton J. Role of the pharmacist in antimicrobial stewardship. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:929–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe TA, Linder JA. Novel approaches to decrease inappropriate ambulatory antibiotic use. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17:511–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belongia EA, Knobloch MJ, Kieke BA, Davis JP, Janette C, Besser RE. Impact of statewide program to promote appropriate antimicrobial drug use. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yates TD, Davis ME, Taylor YJ, et al. Not a magic pill: a qualitative exploration of provider perspectives on antibiotic prescribing in the outpatient setting. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keller SC, Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE, et al. Ambulatory antibiotic stewardship through a human factors engineering approach: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:417–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.