Abstract

Background

We evaluated the effect of early awake prone position administration on oxygenation and intubation requirements and short-term mortality in patients with acute respiratory failure due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia.

Methods

This is an observational-cohort study. Patients receiving mask oxygen therapy in our intensive care units because of acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia were included. The Awake Prone Position (APP) group consisted of patients who were applied awake prone position, whereas non-APP group consisted of patients who were not applied awake prone position. PaCO2, PaO2, pH, SpO2 values and PaO2/FiO2 ratios were recorded at the beginning and 24th hour. Demographic data, comorbidities, intubation requirements, ventilator-free days, length of intensive care unit stay and short-term mortality of the patients were recorded.

Results

The data of total 225 patients were examined, and 48 patients who met our study criteria were included. At the 24th hour, the median SpO2 value of the APP group was 95%, the median PaO2 value was 82 mmHg, whereas the SpO2 value of the non-APP group was 90% and the PaO2 value was 66 mmHg. (p = 0.001, p = 0.002). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups in length of intensive care unit stay and ventilator-free days, but short-term mortality and intubation requirements was lower in the APP group (p = 0.020, p = 0.001)

Conclusion

Awake prone position application in patients receiving non-rebreather mask oxygen therapy for respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia improves oxygenation and decreases the intubation requirements and mortality.

Keywords: COVID-19, Respiratory failure, Prone position, Intensive Care Unit

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, which has led to the pandemic since the end of 2019, can cause acute respiratory failure due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia. Patients with acute respiratory failure must be monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU), largely under the support of mechanical ventilation. Despite close follow-up and treatment in this group of patients, the mortality rate is quite high.1 In previous studies of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), early prone position (PP) application with neuromuscular blockers and low tidal volume administration improved the PaO2/FiO2 ratio and decreased mortality at a moderate level. The PP is known to show a recruitment effect on the dorsal lung, increase lung volume at the end of expiration, increase chest wall elasticity, and reduce alveolar.2, 3, 4 To avoid intubation in moderate-level ARDS cases, awake PP combined with noninvasive mechanical ventilation or nasal high-flow applications can correct ventilation/perfusion incompatibility and provide lung drainage.5 Awake PP is prevalently used by clinicians during mask oxygen or nasal high-flow application in patients with mild to moderate acute respiratory failure after COVID-19. The fact that pulmonary compliance was largely preserved suggests that the benefit from PP may be more than expected. A paucity of literature is available that reports improved oxygenation and reduced intubation requirements when PP was applied during mask oxygenation or nasal high flow in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia.6, 7, 8 None of the previous studies were randomized controlled studies, and their conclusions were largely suggestive not conclusive.

In our study, we evaluated the effect of early awake PP administration on oxygenation and intubation requirements and short-term mortality in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia.

Methods

The study was retrospectively conducted in five COVID-cohort intensive care units in our hospital, including patients from March 15 to June 15, 2020. The study was started after approval from the local ethics committees of our hospital (2807) and the Ministry of Health (2020-04-30T19_46_45), and after registering in the Clinical Trials (NCT04427969). Informed consent form was obtained from the patient or patient relatives. The data of patients >18 years of age who were monitored and treated in the ICU for acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia were retrospectively identified. Patients who developed acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia and received conventional oxygen therapy with nonrebreather mask oxygen upon admission to the ICU were included in the study. Patients who were supported with noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation due to respiratory acidosis (pH <7.30 and PaCO2 >50 mmHg), PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150, Glasgow Coma Scale score <12 points, or hemodynamic instability from the moment of admission to the ICU were excluded from the study. In addition, patients with primary pulmonary pathologies (lung cancer, cardiopulmonary edema, and Kartagener’s syndrome) other than pneumonia, patients who underwent nasal high-flow therapy, and those who applied awake PP < 12 hours in 1 day were excluded from the study.

COVID-19 was diagnosed using a polymerase chain reaction test. The diagnosis of pneumonia was made on the basis of clinical results and the appearance of multifocal frosted glass opacities forming consolidation on computed tomography. Acute respiratory failure was defined as a PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300 despite conventional oxygen therapy using a nonrebreather mask at 6 L.min-1. The FiO2 (%) = 21 + 4 × flow rate (L.min-1) formula was used for the calculation in the patients who received oxygen support through a nonrebreather mask.

The first group (APP) consisted of patients who applied 12–18 hours of awake PP with nonrebreather mask oxygen support, and the second group (non-APP) consisted of patients who had only nonrebreather oxygen support and did not receive awake PP. No patient selection criteria were applied for indicating awake PP. Awake PP was targeted for all patients admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. However, awake PP could not be applied to all patients because of patient refusal or noncompliance.

Age, sex, body mass index, and demographic data of all the patients and comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart disease insufficiency, and chronic renal failure) were recorded. In both groups, the SpO2, PaO2/FiO2, pH, PaCO2, and PaO2 values measured in arterial blood gas at the beginning and 24th hour (after awake PP application for at least 12 hours in the APP group) were recorded.

Conventional oxygen therapy was administered to all patients by using a nonrebreather mask, targeting SpO2 >93% at a flow rate of 6–15 L.min-1. It was aimed at applying awake PP for 18 hours intermittently in a day for all patients. However, the period varied between 12 and 18 hours owing to the uncomfortable position caused by the therapy. Unless treatment failure occurred, awake PP was applied to our patients at least 12 h.day-1. Treatment failure was defined as a PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150, SpO2 <93%, Glasgow Coma Scale score <12, and respiratory acidosis (pH < 7.40 and PaCO2 >50 mmHg). In case of treatment failure, the patients were intubated and received invasive mechanical ventilation.

The patients’ intubation need, ventilator-free days, length of ICU stay, and short-term mortality were recorded. Short-term mortality was defined as death within 28 days of ICU stay, post intensive care hospitalization or home discharge.

Statistical analysis

The data were evaluated using Windows SPSS 15. Descriptive results were obtained as number and percentage distributions for categorical variables and mean and standard deviations and median – interquartile range for numerical variables. For statistical analysis, normal distribution status of numerical values were evaluated according to Shapiro-Wilk test, histogram and Q–Q plots graph and Student’s t-test. Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparisons. For categorical variables statistical analysis, Fisher's exact chi-square test was used when there is a value between 5–25 in any of the cells and Continuity Correction is less than 5. Results are interpreted practically/clinically with significant effect size values. An acceptable level of significance was p < 0.05.

Results

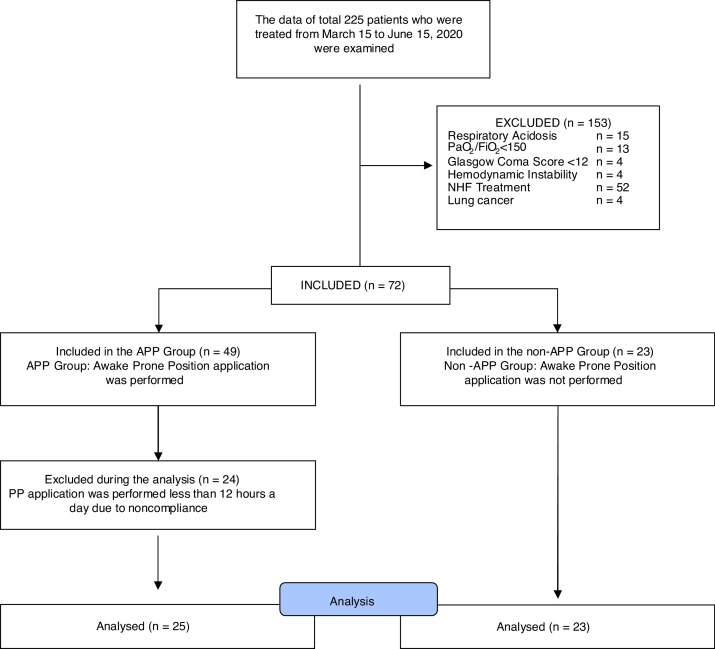

The data of 225 patients who were treated between March 15 and June 15, 2020 were examined. Of the patients, 61 who were admitted to the ICU had already been intubated. Fifteen patients had respiratory acidosis, 13 had PaO2/FiO2 ratios <150, 4 had Glasgow Coma Scale scores <12, and 4 had hemodynamic instability. These 36 patients were supported with noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation. Nasal high-flow treatment was applied in 52 patients. PP application was performed in 24 patients less than 12 hours a day due to patient incompatibility, and four had lung cancer among the comorbidities. For this reason, the data of 177 patients were excluded from the study. The data of 48 patients who met our study criteria were included in the study. The APP group consisted of 25 patients, whereas the non-APP group consisted of 23 patients (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Table 1 lists the demographic data and comorbidity states. The median age of the patients in the APP group was lower than that of the patients in the non-APP group (p = 0.002). We found no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of sex, body mass index, and comorbidity states.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants at inclusion in the study.

| APP (n = 25) | non-APP (n = 23) | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||||

| Age (years) | 62.4 ± 10.9 (43–83) | 72.6 ± 10.1 (51–89) | 0.002a | 0.99 | |

| Body Mass Index (kg.m-2) | 25.1 ± 2.5 (20.2–30.1) | 26.6 ± 3.1 (21.6–36.7) | 0.079b | 0.55 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | Phi | |||

| Sex | Female | 14 (56.0) | 14 (60.9) | 0.732 | 0.05 |

| Male | 11 (44.0) | 9 (39.1) | |||

| Comorbidity | 17 (68.0) | 20 (87.0) | 0.223 | 0.23 | |

| DM | 10 (40.0) | 6 (26.1) | 0.475 | 0.15 | |

| HT | 10 (40.0) | 15 (65.2) | 0.145 | 0.25 | |

| CAD | 2 (8.0) | 4 (17.4) | 0.407 | 0.14 | |

| COPD | 2 (8.0) | 0 | 0.490 | 0.20 | |

| CHF | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.3) | 1.000 | 0.01 | |

| KBY | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0.479 | 0.15 | |

| Cancer | 0 | 2 (8.7) | 0.224 | 0.22 | |

| Other | 6 (24.0) | 9 (39.1) | 0.413 | 0.16 | |

p, Chi-Square Test; BMI, Body Mass Index; DM, Diabetus Mellitus; HT, Hypertension; CAD, Coroner Artery Disease; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF, Congestive Heart Failure; CRF, chronic renal failure.

*Plus–minus values are median (IQR) Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50 and Phi value ≥ 0.30 practically/clinically significant.

Student t and Test.

Mann Whitney U Test.

Moreover, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups in terms of initial SpO2, pH, PaO2, and PaO2/FiO2 values. The initial PaCO2 values in the APP group were higher than those in the non-APP group (p < 0.001; Table 2). No statistically significant differences in pH, PaCO2, and PaO2/FiO2 values were found between the groups at the 24th hour. The APP group had higher 24th-hour SpO2 and PaO2 values than the non-APP group (p = 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively; Table 3). When the changes in the initial values within the 24th hour were compared between the APP and non-APP groups, the decrease in pH value was significantly higher in the non-APP group than in the APP group (p = 0.002). The PaO2 values increased in the APP group, whereas they decreased in the non-APP group, and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The PaCO2 values decreased in the APP group but increased in the non-APP group, and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (p = 0.007). The increase in SpO2 value was significantly higher in the APP group (p = 0.016). The PaO2/FiO2 ratios increased in the APP group and decreased in the non-APP group, but the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 2.

Initial SpO2, PaO2/FiO2 and arterial blood gas values.

| APP (n = 25) | non-APP (n = 23) | p | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| SpO2 (%) | 89 (85.5–93) | 90 (82–96) | 0.860 | 0.01 |

| pH | 7.45 (7.37–7.49) | 7.48 (7.4–7.51) | 0.100 | 0.58 |

| PaCO2 | 36 (33–46) | 30 (25–34) | <0.001 | 1.02 |

| PaO2 | 65 (58–71.5) | 63 (59–79) | 0.368 | 0.37 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 175.7 (156.8–193.2) | 167.6 (159.5–213.5) | 0.649 | 0.28 |

SpO2, Saturation Pulse Oxygen; P/F:PaO2/FiO2, Partial Oxygen Pressure/Fraction of Inspired Oxygen; PaO2, Partial Oxygen Pressure; PaCO2, Partial Carbon Dyoxid Pressure.

*Plus–minus values are median (IQR). Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50 practically/clinically significant p: Mann Whitney U Test #Student t test.

Table 3.

24th hour SpO2, PaO2/FiO2 and arterial blood gas values.

| APP (n = 25) | non-APP (n = 23) | p | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| SpO2 (%) | 95 (92.5–96) | 90 (89–94) | 0.001 | 1.06 |

| pH | 7.46 (7.33–7.485) | 7.40 (7.23–7.48) | 0.268 | 0.38 |

| PaCO2 | 37 (33.5–43.5) | 35 (29–40) | 0.243 | 0.17 |

| PaO2 | 82 (74–92) | 66 (60–70) | 0.002 | 0.80 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 190.2 (166.7–214) | 164.9 (154.1–186.5) | 0.124 | 0.20 |

SpO2, Saturation Pulse Oxygen; PaO2/FiO2, Partial Oxygen Pressure/Fraction of Inspired Oxygen; PaO2, Partial Oxygen Pressure; PaCO2, Partial Carbon Dyoxid Pressure.

*Plus–minus values are median (IQR). Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50 practically/clinically significant p: Mann Whitney U Test.

Table 4.

Changes in SpO2 and arterial blood gas values at the initial and 24th hour.

| APP (n = 25) | non-APP (n = 23) | p | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| SpO2 (%) | 5 (0.5/10) | -1 (-54/5) | 0.016 | 0.74 |

| pH | 0 (-0.025/0.045) | -0.05 (0/-0.19) | 0.002 | 0.051 |

| PaCO2 | -1 (-4.5/4) | 4 (-1/14) | 0.007 | 0.086 |

| PaO2 | 16 (5.5/31.5) | -1 (-14/7) | <0.001 | 1.14 |

SpO2, Saturation Pulse Oxygen; P/F:PaO2/FiO2, Partial Oxygen Pressure/Fraction of Inspired Oxygen; PaO2, Partial Oxygen Pressure; PaCO2, Partial Carbon Dyoxid Pressure.

*Plus–minus values are median (IQR). Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50 practically/clinically significant p: Mann Whitney U Test.

We found no statistically significant difference between the groups in length of ICU stay and ventilator-free days, but the short-term mortality and intubation requirements were lower in the APP group than the non-APP group (p = 0.020 and p = 0.001, respectively; Table 5).

Table 5.

ICU stay period, ventilator-free period, mortality rate, and intubation need.

| APP (n = 25) | Non-APP (n = 23) | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| Ventilator free period (day) | 3,5 (3–6,5) | 2 (2–3) | 0,004 | 1,64 |

| ICU stay period (day) | 5 (4–11) | 8 (4–12) | 0,258 | 0,30 |

| n (%) | n (%) | Phi value | ||

| Intubation requirements | 8 (32) | 19 (82,6) | 0.001 | 0.51 |

| Mortality rate | 9 (36.0) | 16 (69.6) | 0.020 | 0.37 |

ICU, Intensive Care Unit.

*Plus–minus values are median (IQR). Cohen’s d ≥ 0.50 and Phi value ≥ 0.30 practically/clinically significant.

p: Mann Whitney U Test and -Chi-Square Test.

Discussion

The prevalence of acute respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia is approximately 19%. Based on the preliminary data, the oxygen treatment requirement is 14% and the ICU admission and mechanical ventilation requirement is 5%.9

The initial data demonstrated that the risk factors associated with ICU admission are as follows: age >60 years, male sex, diabetes, and immunodeficiency, while cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, and diabetes were associated with high mortality.9, 10 In our study, the median age of the patients in both groups was >60 years and most patients were male. The lower median age of the PP group might be associated with older patients being less compatible with PP application. A high proportion of patients in both groups had a history of comorbidities, and no significant difference was found between the groups in terms of the presence of comorbidities. Among the comorbidities, diabetes and hypertension had high prevalence rates.

Acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia was assessed as ARDS because it largely met the Berlin criteria at the initial stage.11 With the acquired experience, two different phenotypes were identified (L and H phenotypes). In the prevalently-observed L phenotype, respiratory mechanics were well preserved in spite of severe hypoxia, lung weight did not increase, and the ventilation/perfusion ratio decreased. Moreover, the H phenotype was considered the conventional ARDS.12

The treatment recommendations for respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia are largely based on ARDS data, which show that early PP application >12 hours in a day reduces mortality and improves oxygenation. Moreover, PP shows a recruitment effect on the dorsal lung, reduces alveolar shunt, and increases end of expiration lung volume and chest wall elasticity.2, 3, 4

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines recommend PP application for 12–16 hours as a weak recommendation with a low evidence level for patients with COVID-19.13 Studies on the clinical outcomes of PP application are unavailable in this group of patients, which are known to have different respiratory mechanics from ARDS.

Difficulties exist, such as extracting the intubation tube used during PP application in an intubated patient, preventing pressure wounds, reducing the need for deep sedation and neuromuscular blockers, and meeting the large number of personnel required for application.14, 15 Therefore, the PP application rate was reported to be 32.9% in conventional ARDS and 11.5% in respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia because of excess contact.10, 14 However, the fact that additional staff and sedative agents are not required for awake PP leads to ease of application.

Based on the preliminary data from China and Italy, noninvasive mechanical ventilation or nasal high-flow applications were not preferred in patients with inadequate response to mask oxygenation because of high aerosolization, and early intubation was recommended.16, 17 However, the high postintubation mortality rate and severe ICU resource constraints led to the search for a new treatment strategy.18 As a result, awake PP applied along with mask oxygenation or nasal high flow was introduced.6, 7

Ding et al.5 reported the positive effects of PP administration on oxygenation in patients with ARDS who underwent noninvasive mechanical ventilation and nasal high-flow therapy. They demonstrated that PP application in awake patients minimizes complications and the application difficulties observed in intubated PP. Moreover, awake PP is prevalently preferred for patients with COVID-19 in clinical practice; however, limited literature is available on this topic.6, 7, 19

In the study by Caputo et al.7 in 50 patients admitted to the emergency service who had a COVID-19 preliminary diagnosis and required oxygen mask support, the effect of awake PP application for 5 minutes on SpO2 changes was evaluated. The average SpO2 was initially 80% in room air, 84% after oxygen support, and 94% after 5 minutes of awake PP. Moreover, the intubation requirement was 24% within 24 hours. In this study, which did not perform arterial blood gas and mortality evaluations, short-term PP application under oxygen support was demonstrated to improve oxygenation in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. In our study, the average initial SpO2 value was 89% in both groups. After PP, these values increased, and the intubation requirement was reported to be 32% in the PP group and 82.6% in the non-PP group. In our study, the follow-up was not limited to 24 hours, and the median number of ventilator-free days was 3.5 days in the PP group and 2 days in the non-PP group.

In a case report, a 68-year-old patient with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 received awake PP application with nasal high flow for 16–18 hours daily. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio increased from 100 to 150 to 250, and no intubation was required for 4 days. Moreover, the patient’s abilities to participate in physiotherapy, conduct phone calls with family, and receive oral nutrition were highlighted as significant advantages.19 In a Letter to the Editor, the success of COVID-19 treatments in the Jiangsu Province of China was reported to be higher and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was lower than that in other provinces; moreover, self-PP was demonstrated as a reason for the treatment success.6

In our study, we found no significant difference in the initial PaO2/FiO2 ratio between the two groups. The median PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 175.7 in the PP group and 167.6 in the non-PP groups. At the 24th hour, the median PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 190.2 after PP application and 164.9 in the non-APP group. Although the difference in the change in PaO2/FiO2 ratio between the groups was not statistically significant, the increase in PaO2/FiO2 ratio with PP application was remarkable. The PaO2 and SpO2 values increased significantly with awake PP application. A remarkable point was that although the initial PaCO2 value was higher in the PP group, it decreased at the end of 24 hours in the PP group but increased in the non-APP group.

Although the figures reported from different countries and centers vary, the mortality from COVID-19 due to respiratory failure in the ICU ranged from 30% to 40%; however, this rate reached 90% in patients with an invasive mechanical ventilation need.18, 20, 21 In our study, the mortality rate was as low as 36% in the patients who received awake PP application and both the intubation requirement and mortality rates were as high as 69.6% in the non-APP group.

Our study is limited in that it was not a prospective randomized controlled study.

In conclusion, awake PP applied in patients receiving nonrebreather mask oxygen treatment for respiratory failure due to COVID-19 pneumonia improved oxygenation and decreased the intubation requirement and short-term mortality rate.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guérin C., Reignier J., Richard J.-C., et al. Prone Positioning in Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2159–2168. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallet R.H. A comprehensive review of prone position in ARDS. Respir Care. 2015;60:1660–1687. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munshi L., Del Sorbo L., Adhikari N.K.J., et al. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:S280–8. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-343OT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding L., Wang L., Ma W., et al. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: A multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2738-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Q., Qiu H., Huang M., et al. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:2–5. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caputo N.D., Strayer R.J., Levitan R. Early Self-Proning in Awake, Non-intubated Patients in the Emergency Department: A Single ED’s Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27:375–378. doi: 10.1111/acem.13994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghelichkhani P., Esmaeili M. Prone Position in Management of COVID-19 Patients; a Commentary. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8:1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Rossi S. COVID-19 pneumonia: ARDS or not? Crit Care. 2020;24:1–3. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Caironi P., et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alhazzani W., Møller M.H., Arabi Y.M., et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854–887. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guérin C., Beuret P., Constantin J.M., et al. A prospective international observational prevalence study on prone positioning of ARDS patients: the APRONET (ARDS Prone Position Network) study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:22–37. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4996-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCormick J., Blackwood B. Nursing the ARDS patient in the prone position: The experience of qualified ICU nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17:331–340. doi: 10.1054/iccn.2001.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livingston E., Bucher K. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1335. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slessarev M., Cheng J., Ondrejicka M., et al. Patient self-proning with high-flow nasal cannula improves oxygenation in COVID-19 pneumonia. Can J Anesth. 2020;67:1288–1290. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01661-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quah P., Li A., Phua J., et al. Mortality rates of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: A systematic review of the emerging literature. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du R.H., Liu L.M., Yin W., et al. Hospitalization and critical care of 109 decedents with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:839–846. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]