Abstract

Moral injury emerged in the healthcare discussion quite recently because of the difficulties and challenges healthcare workers and healthcare systems face in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moral injury involves a deep emotional wound and is unique to those who bear witness to intense human suffering and cruelty. This article aims to synthesise the very limited evidence from empirical studies on moral injury and to discuss a better understanding of the concept of moral injury, its importance in the healthcare context and its relation to the well-known concept of moral distress. A scoping literature review design was used to support the discussion. Systematic literature searches conducted in April 2020 in two electronic databases, PubMed/Medline and PsychInfo, produced 2044 hits but only a handful of empirical papers, from which seven well-focused articles were identified. The concept of moral injury was considered under other concepts as well such as stress of conscience, regrets for ethical situation, moral distress and ethical suffering, guilt without fault, and existential suffering with inflicting pain. Nurses had witnessed these difficult ethical situations when faced with unnecessary patient suffering and a feeling of not doing enough. Some cases of moral distress may turn into moral residue and end in moral injury with time, and in certain circumstances and contexts. The association between these concepts needs further investigation and confirmation through empirical studies; in particular, where to draw the line as to when moral distress turns into moral injury, leading to severe consequences. Given the very limited research on moral injury, discussion of moral injury in the context of the duty to care, for example, in this pandemic settings and similar situations warrants some consideration.

Keywords: COVID-19, ethics, moral conflict, moral injury, moral integrity, pandemic

Introduction

Today, health services globally face one of the most significant challenges in their history. Worldwide, healthcare systems have been significantly impacted but continue to depend on the deep commitment and sacrifice on the part of their healthcare workers. They are at the front line of the global pandemic of COVID-19, and their situation has prompted us to consider the risk of suffering from moral injury.1,2 As a concept, moral injury first appeared in the literature in the 1990s3 in the context of combat and war circumstances – however, it has recently been brought up more broadly in the healthcare context.4–6 This article aims to synthesise the very limited evidence from empirical studies on moral injury and to develop a better understanding of the concept of moral injury and its importance in the healthcare context.

Background

When faced with the global pandemic of the coronavirus7 after the epidemic started in China,8 many countries encountered a serious threat to their healthcare systems due to the exponential growth of positive cases and deaths. Horrific scenes from wards across China, Italy and Spain illustrate the severity of the situation and the overload of patient cases which hospitals cannot manage because of lack of resources (beds, respirators, personal protective equipment (PPE)) and exhausted healthcare professionals.9 The exhaustion of healthcare professionals is mostly due to their active role of being at the front line and working overtime, not seeing their families, and not having adequate rest. They also suffer from mental health exhaustion by witnessing patients in life-threatening situations and not being able to help them; or if able to help, needing to prioritise the scarce resources they have.10 This requires decisions regarding who will have the chance to survive.11 Health workers also face the anxiety of getting infected and passing on the infection to their loved ones when they go home.12 Although prepared to face many difficult situations during their professional education and career, working on the front line during a pandemic is likely to have exceeded their worst fears and will potentially affect them severely and have long-term consequences.13,14 Making difficult, even impossible, decisions, working under pressure and not fulfilling their non-negotiable moral and professional principle ‘first do no harm’ may lead to moral injury.1,2 Decision making in these situations often ranges across issues such as the allocation of scarce resources, caring for severely ill patients, aligning patient needs with family, and balancing with one’s own physical and mental health needs. Very often this results in situations where one cannot say to the family ‘We did all we could’ but only ‘We did our best with the staff and resources available, but it wasn’t enough’,2 which become, as pointed out by Greenberg and colleagues, the seeds of moral injury.

The consequences of similar situations can be seen in the relatively recent example of the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa in 2014–2016. Here, at the end of the outbreak, the epidemic had severe physical and mental health consequences for healthcare workers and the wider community, resulting in death of 50% of infected healthcare workers and countless people suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).15 As Bartzak16 has argued, the occurrence of PTSD might be a manifestation of moral injury, and this causal relationship has also been observed to be moderate-to-strong in a systematic review of potential morally injurious events at the work place in a military and non-military context.17 The term moral injury was born in the PTSD context. In the 1990s, the psychiatrist Shay3 observed that some Vietnam veterans did not suffer from PTSD, but carried within themselves a kind of wound, which they named moral injury. Shay emphasises three requirements for something to be recognised as moral injury: ‘Moral injury is present when (i) there has been a betrayal of what is morally right, (ii) by someone who holds the legitimate authority and (iii) in a high-stakes situation’.18(p. 183) Later research demonstrated that in 28% of war veterans, moral injury was related to ethical situations they had faced where they did not know how to respond19; in other words, they faced a moral uncertainty.20,21

However, Shay’s definition focuses mostly on the power holders, and the feelings of powerlessness leading to helplessness and hopelessness, and the loss of faith in the goodness of the world and humanity; encompassing symptoms such as feelings of guilt or shame. These feelings are linked to a lack of trust towards self and others, social isolation, and emotional numbing, which arise from the potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs).22

Litz and colleagues23 describe another form of the concept of moral injury, focusing more on a personal perspective, by defining PMIE as ‘perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations’,23(p. 700) which may leave long-lasting emotionally, psychologically, behaviourally and spiritually harmful impacts. The exposure to PMIEs may lead to a wide range of biological, psychological/behavioural, social and religious/spiritual sequelae, ultimately manifesting as severe distress and functional impairments known as ‘moral injuries’.24 Through their integrative review, Griffin and colleagues24 observed the absence of a consensus definition and gold-standard measure for moral injury, as well as scant study of moral injury outside of military-related contexts. More recently, several measurement tools have been developed: Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES),25 Moral Injury Appraisals Scale (MIAS),26 and Moral Injury Symptom Scale–Military Version (MISS-M).27

Moral injury has appeared in the context of exceptional circumstances, typically in military or war settings.3 However, the concept of moral injury has recently been recognised in other contexts among other professionals who work with humans, such as the police,28 journalists29 and in emergency medicine, such as medical students in prehospital care30 or paramedics.31 Murray and colleagues30 demonstrated that the witnessing experiences of medical students, in the emergency medicine wards, of events challenging one’s moral code, acts of violence, particularly those including children, having its consequences in the form of secondary/vicarious trauma seem most effectively encompassed in the notion of moral injury. The actions taken, including violations of human rights, restrictions or violations of autonomy or similar, are harmful to individuals, and non-action in such situations may seep into daily practice. This has been presented in the ethics literature and called a slippery slope.32 Over time, these moral injury experiences may affect/impact daily practice, thus undermining and dehumanising the caregiving practice.33 In this context, witnessing severe immoral or unethical actions or behaviours may have profound consequences and may manifest as moral injury in some people.

The impact on everyday practice was one of the main motivators for Talbot and Dean4 in extending the use of the concept of moral injury to the healthcare context. They argue that physicians are not burning out but are suffering from moral injury, described as ‘the challenge of simultaneously knowing what care patients need but being unable to provide it due to constraints that are beyond our control’.5(p. 401) They argue that although the behavioural signs that concern them may look like those of burnout, the concept of moral injury better describes their experience – which is filled with anguish. Talbot and Dean have established a non-profit advocacy group called Moral Injury of Healthcarei to promote public awareness of moral injury in the healthcare domain. Dean and colleagues5 emphasise the difference between burnout and moral injury by arguing that in burnout, the root of the problem lies in the broken individual who lacks resilience. In contrast, in the case of moral injury, the root of the problem is in the broken system that, using a reductionist business model, has prioritised profit over healing.

However, the use of the term moral injury in healthcare has encountered some criticism because of its necessity and similarity to other existing concepts. For example, it is argued that the term burnout itself does not blame the physician, nor does it absolve the healthcare system of its responsibilities. Second, it is argued that it is unnecessary to have another concept besides moral distress, which is a term already recognised in medicine, and finally, it is claimed that ‘moral injury in medicine is not well operationalised or researched’.34 Furthermore, even Kopacz and colleagues6 point out some overlap in the conceptual understanding and signs and symptoms, and see an opportunity of bringing the notion of moral injury among healthcare professionals into the ‘burnout’ discussion. They argue that including moral injury in the ‘burnout’ discussion might also help combat the stigma surrounding mental health disorders and treatment. However, such consideration risks neglecting the morality aspects in moral injury, by erroneously considering moral injury purely as mental disorder/issue and failing to recognise the ethical aspects. The critique raised regarding the conceptual clarity of the term moral injury has motivated us to investigate further the idea of moral injury within the healthcare context, including exploring the possible differences from/similarities to the concept of moral distress.

Empirical studies on moral injury

Systematic literature searches were conducted in April 2020 using two electronic databases, PubMed/Medline and PsychInfo, the most comprehensive and relevant databases in healthcare, to identify the relevant articles for the review. The search sentence included terms related to moral injury and healthcare. The sentence was the following: Moral AND (injur* OR distress OR stress OR damag* OR residue OR suffering) AND (nursing OR nurse OR nurses OR physician* OR doctor OR doctors OR health care OR healthcare). The search focused on titles and abstracts, resulting in a total of 2044 hits (PubMed/Medline n = 1407, PsychInfo n = 637). Inclusion criteria were that the article (1) was an empirical study report in a peer-reviewed journal, (2) was a study reporting health professionals’/care providers’ perspective on the topic and (3) analysed healthcare professionals’ moral injury (or damage or suffering). Excluded were articles that were (1) commentaries, discussions or editorials; (2) focused on patients or veterans; or (3) focused only on the topic of moral distress.

The retrieval of empirical articles followed a two-phased procedure. First, the screening of citations focused on titles and abstracts. Two researchers performed the screening (n = 2044). All the identified citations were examined, and where reviewers disagreed, a third reviewer confirmed the inclusion or exclusion of the citation. Second, two researchers assessed the eligibility of the citation based on the full text (n = 8). After consensus agreement, the full texts were included in the review (n = 7), and one of the selected texts not focusing on moral injury was excluded.

Results

Description of the studies included

Altogether seven studies about ‘moral injury’ or similar concepts were identified from the records. The majority of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 3), followed by Australia, Sweden, Denmark and Korea, one in each. The first empirical study appeared in Sweden in 2008.35 It is important to note here that the cultural aspects in these empirical studies from different parts of the world are also worth taking into consideration.

Moral injury as a research topic

The concept of moral injury was the topic in two studies.36,37 Other concepts used in studies were stress of conscience,35 regrets for an ethical situation,38 moral distress and ethical suffering,39 guilt without fault,40 and existential suffering with inflicting pain.41 Although only two of the papers do use directly the term moral injury, the others indirectly refer fully or partially to moral injury as an individual’s internal reaction to moral wrongdoing (action or non-action) or to morally injurious events.

Research methods used in the studies

The studies were descriptive and cross-sectional (n = 4)35,36,38,39 in nature or used mixed-methods designs.37,40,41 Data collection methods included surveys (n = 2),35,38 interviews (n = 2)36,39 or both.40,41 The studies focused on healthcare professionals in general (n = 1), nurses (n = 3) or medical (n = 1) professionals, or both nurses and physicians (n = 2). Sample sizes varied from 1439 to 423.35 The contexts in which the studies were carried out included hospitals,35 a clinical practice not specified,38 critical care in university hospitals,39 neonatal units,41 midwifery and obstetrics,40 combat/war context,36 or en route military nursing.37

Factors associated with moral injury

Moral injury, particularly in the case of military healthcare personnel and war zone scene events, has mostly been associated with traumatic events, such as betrayal, disproportionate violence, incidents involving innocent civilians or even experiencing violence on their own skin.36 Those involved in military contexts were torn between the military mission and their professional obligation to help patients and people in need in situations where the military mission always takes precedence. Such contexts often led to acts of omission or commission which transgressed participants’ deeply held beliefs. These acts created inner conflict leading to psychosocial sequelae, manifesting in most cases as sleep problems, anger, grief or sadness.36 Participants emphasised situations, particularly when caring for injured children, where they felt powerless as they did not have the skills to care for severely injured children, and they only performed the mechanics of care provision, which led to a sense of being void of empathy. Such acts resulted in regrets in having witnessed or experienced such situations.37 However, vulnerability to moral regret has not only been discovered among healthcare personnel in the combat context, but also among healthcare personnel involved in ethically distressing situations. These participants perceived that well-intended actions may sometimes cause injury, harm or even death to their patients, from beginning-of-life40 to end-of-life situations.38

Nurses have witnessed that ultimately, these difficult ethical situations where they are faced with unnecessary patient suffering and a feeling of not doing enough, tend to lead to a sense of hopelessness and helplessness, resulting in burnout among nurses caring for these patients.38 Such situations produce inevitable stress of conscience when individuals are not able to follow their own conscience and have a sense of moral burden, that is, are unable to deal with moral problems which are the result of restrictions and boundaries set by their superiors and managers.35 Stress of conscience emerges particularly when external constraints force us to prioritise tasks over human dignity, causing ethical insensitivity or ambivalence among healthcare personnel. The resulting mechanistic provision of care despite the sense of accomplishment with tasks may lead to ethical suffering.39 However, healthcare personnel are keen to empathise with the patient, especially in cases involving vulnerable groups of patients, such as suffering children in neonatal wards, while experiencing more than ever a feeling of powerlessness in the face of their existential suffering.39 In fact, this ability to sense and try to understand the existential suffering of others demonstrates the healthcare personnel’s ability to respect other human beings and their sensitivity to others’ suffering, followed by the desire to relieve their suffering and not to inflict pain.39

Of the seven studies, only that of Gibbons and colleagues36 makes a clear distinction between moral distress and moral injury, relying on the notion of Fry and colleagues42 stating that ‘moral distress among military health professionals occurs when an individual makes a moral judgment about a patient situation but does not act accordingly. This occurs when actions are obstructed by an organisation or by a more powerful individual’.36(p. 248) On the contrary, in defining ‘moral injury’, Gibbons and colleagues36 refer to the work of Litz and colleagues,23 stating that ‘Moral injury involves a deeper emotional wound and is unique to those who bear witness to intense human suffering and cruelty’.36(p. 248) Distinguishing one from the other, they emphasise that their respondents do not suffer from posttraumatic stress, but from moral injury, which leaves a deep trace in their inner self, and suggest that the only treatment is forgiveness and compassion. Nurses/midwives and physicians need to recognise and acknowledge guilt or guilty feelings40 and forgive themselves by making peace with the traumatic exposures that haunt them because of moral injury. Not doing so can lead to self-harm, problematic substance use43 and even suicide.36

Discussion

Discussion and concept contextualization

Given the very limited empirical literature on moral injury, this review seeks to stimulate much-needed discussion on the topic of moral injury among healthcare professionals in various healthcare environments. It also commences an investigation of the relationship of the concept of moral injury with those of moral distress and burnout, stress of conscience, regrets for an ethical situation, ethical suffering, guilt without fault and existential suffering with inflicting pain. Moral injury has been strongly linked to exceptional circumstances, mostly followed by some internal moral conflict raised by traumatic events in combat conditions, for example, witnessing severe violence against human life and having a responsibility to act in such circumstances.36,37 Furthermore, other difficult, ethically stressful situations which can manifest in caring for patients at any point in the life cycle from birth40 to death38 have also left a deep emotional trace among healthcare personnel in the form of regret and guilt, as they wish they could have acted differently and judge themselves harshly, even though it may not have been possible to do otherwise at the time. However, as indicated by Gibbons and colleagues,36 moral injury is a deep emotional wound that may be inflicted on an individual due to a unique set of circumstances rooted in witnessing a situation of intense human cruelty and suffering. In moral injury, not only do traumatic events cause distress, but the immorality of the action (our own or that of others)19 which violates our deeply held beliefs (moral compass) or conscience produces a deep emotional reaction with long-lasting consequences.44 The morality aspect of moral injury not only creates temporary distress but also internal dissonance from acting in a way that conflicts with moral beliefs, creating a breach in the individual’s moral identity and inner self, which can result in long-standing anxiety and social withdrawal.36

We argue that the description of moral injury in healthcare provided by Talbot and Dean4 introduces some conceptual confusion because it practically corresponds to what is currently understood as moral distress: being morally distressed by knowing what is good for the patient but being unable to provide it because of constraints that are beyond our control. These constraints which are beyond our control might give rise to traumatic, morally distressing situations, but the authors later clarify this as in fact referring to the broken system which prioritises profit over healing and not to the traumatic circumstances. Moreover, they emphasise that the antecedents to this are not high-stakes situations, but institutional or healthcare system constraints, which in their description better corresponds to moral distress. Furthermore, describing the shared psychological consequences with moral distress such as sense of betrayal of values, internalising anguish and, finally, burnout implies they refer to moral distress. Therefore, at the moment, it may seem that healthcare professionals do not suffer from burnout, but if these consequences of moral distress are underestimated and not addressed in a timely manner, they might do so in the future. Healthcare professionals,45–47 including leaders and managers,48,49 face many ethical dilemmas, problems and challenges in their daily work. Research has reported several situations where individual professionals are faced with unethical behaviour of others, or witness abuse or neglect committed by professionals in healthcare settings (older people care settings),50 by other patients (in care homes for people with memory disorders) or by family members (e.g. intimate partner violence). These situations have mostly been associated with the occurrence of moral distress among caregiving professionals, particularly among nurses – having direct impact on nurses’ relationship with patients consisting in fiduciary duty, fidelity and loyalty and at the end also affecting the duty to care. Their vision of moral injury has commonalities with the historical development of the moral distress concept, initially defined by Jameton as ‘when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action’.20 Later on, Jameton related this concept to the ‘feeling of guilt’,20(p. 283) clarifying moral distress through two stages: the first, initial one ‘involves feelings of frustration, anger, and anxiety people experience when faced with institutional obstacles and conflict with others about values’ while the second, reactive one ‘is the distress that people feel when they do not act upon their initial distress’.21(p. 544) Jameton’s work in this area had significant influence on the first empirical research study performed by Wilkinson.51 Wilkinson described moral distress as ‘the psychological disequilibrium and negative feeling state experienced when a person makes a moral decision but does not follow through by performing the moral behaviour indicated by that decision’.51(p. 16) Although Wilkinson provided a new definition, it did not clarify what it means to experience psychological disequilibrium52; however, she extended the causes of moral distress from a focus on external causes such as institutional constraints to include internal causes as well.

This shift from external to internal helped Corley53 to further develop the notion of the moral sensitivity52 and to redefine the concept as ‘a consequence of the effort to preserve moral integrity when the persons act against their moral convictions’.53(p. 645) In particular, she focused on moral sensitivity and commitment in nursing, arguing that when professional goals are impeded, moral goals are also obstructed. This is particularly true in situations in which nurses ‘have moral sensitivity and commitment, but lack moral courage or moral autonomy, they suffer moral distress’.53(p. 647) This lack of moral courage and moral autonomy might be seen in cases of unfinished or missed care,54 evolving into moral distress that ‘arises from a number of different sources and that (mostly) impacts negatively on nurses’ personal and professional lives and, ultimately, harms patients’.46(p. 150) Within the frame of the impact of moral distress, nurses can become desensitised, or passive, silent, deaf and blind to moral challenges.55 Despite Jameton’s definition and Wilkinson and Corley’s revisions, some authors have pointed criticism at the inconsistency of the moral distress concept and emphasised a need for a broader conceptual redefinition. Fourie45 insisted that moral distress needs to be understood as a psychological response to morally challenging situations of moral constraint or moral conflict.56 Campbell et al.,57 on the contrary, made a substantial revision of the definition by emphasising moral distress as ‘one or more negative self-directed emotions or attitudes that arise in response to one’s perceived involvement in a situation that one perceives to be morally undesirable’ (p. 6). However, these conceptual redefinitions have brought only vagueness and more confusion, as pointed out by Tigard52 Tigard argues that it is not a new definition of moral distress that is needed but the adequate understanding of the nature of moral distress, because most researchers have focused only on its causes and perceived it as something negative. Tigard further argues that moral distress emerges from moral conflict and can be understood twofold: as something negative and undesired manifesting in irrational fear or aversion, that is, phobia, and as something useful and desirable, demonstrating possession of moral sensitivity and values.58

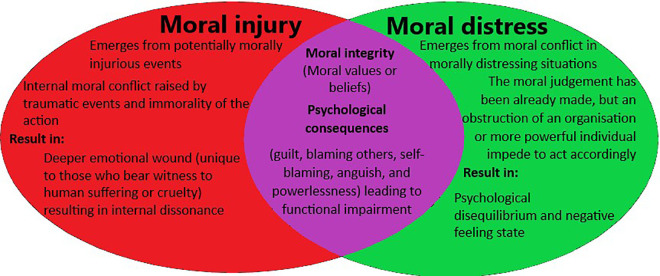

Taking into consideration the short overviews of moral injury and moral distress, we may perceive that they have some commonalities, but also the differences between them (Figure 1). First, among the commonalities, is the moral integrity aspect, where they both reflect the internal relation to moral values and beliefs. Second is that they have some mutual psychological consequences such as sense of guilt, blame towards self and others, anguish and sense of powerlessness. Besides their commonalities, they also differ in terms of the context where they occur. Moral injury emerges from the PMIEs followed by internal moral conflict caused by traumatic events and immorality of the action. Moral injury occurs in PMIEs consisting of external factors (high-stakes situations, beyond our control, broken system) and internal factors (perpetrating, failing to prevent or bearing witness to transgression of deeply held moral beliefs). On the contrary, moral distress emerges from moral conflict in morally distressing situations caused by external constraints (situational, legal, nursing/hospital administration or policies) or internal characteristics (moral sensitivity, threatened moral values, thwarted moral actions, feeling powerlessness).59 They also differ in severity of the resulting consequences for the individual. Moral injury creates a deep emotional wound unique to those who bear witness to human suffering and cruelty. Moral distress results in psychological disequilibrium and negative feeling states (blaming others, self-blaming, self-criticising, depression, anxiety, embarrassment, anguish, sarcasm manifesting in psychological distress) and can also have a negative impact on patient care (loss of ability to provide care, loss of integrity betrayal of values and overall impediment of ethical practice), leading to reduced job satisfaction and burnout, and ultimately to leaving the profession.59 Some of the consequences of moral distress may also be found among the consequences of moral injury (guilt, blaming others, self-blaming, anguish and powerlessness) leading to functional impairment.24 The main difference between moral distress and moral injury is that moral distress represents a form of situational problem (due to the external or internal constraints), while moral injury represents an experience of the problem that results in a long-lasting change to an individual’s sense of losing hope, trust, integrity and so on. In fact, moral distress represents a challenge which may be relatively easy to prevent, if the external constraints are removed and the internal constraints mitigated by reinforcing and increasing moral resilience directly increasing the moral sensitivity level and quality of care provision.60,61 On the contrary, moral injury results in long-term emotional scarring or damage contributing to permanent numbness, malfunctioning and social isolation, which may on the other hand result, if treated in time, in a posttraumatic growth.

Figure 1.

Interplay between moral injury and moral distress.

However, we would also not exclude the possibility that some cases of moral distress may turn into moral injury with time, and in certain circumstances and contexts. The relationship between these two concepts needs further investigation and confirmation through empirical studies, particularly in terms of where to draw the line as to when significant moral distress turns into moral injury leading to severe consequences. ‘Moral injury’, as a new concept in healthcare, might help in providing the basis for a broader understanding of ‘moral distress’ sought by Fourie45 and Campbell et al.57 Some empirical studies have already demonstrated a correlation between moral distress and compassion fatigue.62,63 Exposure to traumatic and stressful events, and in some cases even to potentially injurious events, might elevate the level of compassion fatigue, ultimately resulting in moral injury and possibly, burnout.

The COVID-19 global pandemic context might shed some new light on insights about morally injurious experiences among healthcare professionals, because many of them will be unable to contextualise, justify and accommodate their actions, which might bring about the long-lasting impairment of moral injury. There is good reason to believe that this crisis will have a strong impact on healthcare workers, from mental health and other perspectives (e.g. economically, as family bereavements). Therefore, now would be a timely moment to speak about moral injury among healthcare professionals.6 Recent studies from China confirm that healthcare workers who were in direct contact with COVID-19 patients reported elevated symptoms of depression (50.4%), anxiety (44.6%), insomnia (34%) and distress (71.5%), and nurses reported more severe degrees of all measurements of mental health symptoms than other healthcare workers.64 Interestingly, some studies65 even warn about the risk of medical staff who are not on the front line, particularly nurses, experiencing much higher vicarious traumatisation scores than those in non-healthcare work settings.

These enormous stresses might also lead to poor decisions and mistakes, or even dissatisfaction with the care provision to their patients, which may result in a sense of guilt, regret and moral injury. The conflict between duty to care, as a responsibility of a professional, and traumatising events places a significant ethical burden on healthcare professionals, leaving a serious impact on their mental health. However, the current studies have not assessed the moral injury aspect in respect to traumatic events within the healthcare context, such as witnessing innocent deaths as a result of making moral decisions in triage prioritisation, lack of and allocation of resources, and a sense of powerlessness and hopelessness in the face of overcrowded hospitals. These situations have challenged healthcare workers’ decision-making in having altruistic and even existential connotations particularly in already broken healthcare system, such as choosing between their professional duties and safeguarding themselves and their family members. Furthermore, besides the shocking experiences of witnessing injustice towards patients, the pressure becomes even harder in situations involving their own colleagues with whom they have worked together caring for patients; now, they need to provide care for their colleagues and make tough decisions at their bedside or bear witness to decisions that are beyond their control to influence. It is being argued that the reality of moral injury among healthcare professionals caused by the exposure to certain traumatic events and situations in healthcare contexts, such as the current COVID-19 crisis, deserves to be adequately addressed. This is in order to implement timely, preventive intervention measures to build additional resilience, and to enable those affected the possibility of receiving the needed help and support to survive these traumatic, injurious sets of experiences and continue to work effectively in our health services.

Turning back to the question posed by the critics of the necessity of the concept of moral injury,34 we argue that it fits perfectly to the current perspective of healthcare professionals. Moreover, the moral injury concept might be an answer to the many challenges faced within the conceptual redefinitions of moral distress, such as broadening it45,57,66 or turning it into an umbrella concept67 covering a range of various experiences of individuals who are morally constrained. These attempts, to date, have been unsuccessful, and even counterproductive, leading to dissolution of the significance and importance of moral distress. Introducing the concept of moral injury into healthcare might contribute to the establishment and concise definition of moral distress by preserving its useful and positive aspect as emphasised by Tigard.58 This positive aspect refers to the individual’s moral sensitivity and integrity in the form of moral courage. However, the negative aspect of moral distress endorsed by Tigard, which he describes as a phobia ‘…a state wherein one is truly at odds with herself…’68(p. 368) is more suited and corresponds better to the moral injury concept than to moral distress. Therefore, adopting the concept of moral injury into healthcare does not mean undermining the concept of moral distress; on the contrary, it is more likely to increase its definitional/conceptual clarity.

Conclusion

With this review, our aim is to consider the idea of moral injury and investigate the value of its use in the healthcare context. We argue that ‘moral injury’ is a useful concept in helping to understand the experience some healthcare professionals have as they carry out their work in situations that are at times extraordinarily demanding and even traumatic. However, our intention is not to establish firm grounds for this new concept in healthcare, but to start a discussion and to motivate further theoretical and empirical research. The acknowledgement of the existence of moral injury among healthcare professionals should impact practice, especially patient care provision and healthcare professionals’ inner well-being.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and useful comments, which helped us to improve our paper in clarity and precision.

Note

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This research has been funded by the STSM grant of the RANCARE Cost Action CA15208 funded under Horizon 2020, and also in part supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under project number UIP-2019-04-3212.

ORCID iDs: Anto Čartolovni  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9420-0887

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9420-0887

Minna Stolt  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1845-9800

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1845-9800

P Anne Scott  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5790-8066

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5790-8066

Riitta Suhonen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4315-5550

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4315-5550

Contributor Information

Anto Čartolovni, Catholic University of Croatia, Croatia; University of Hull, UK.

Minna Stolt, University of Turku, Finland.

P Anne Scott, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland.

Riitta Suhonen, University of Turku, Finland.

References

*Included in the review.

- 1.Williamson V, Murphy D, Greenberg N. COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. Occup Med 2020; 70: 317–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, et al. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during Covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020; 368: m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shay J. Achilles in Vietnam: combat trauma and the undoing of character. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talbot SG, Dean W. Physicians aren’t ‘burning out’: They’re suffering from moral injury – STAT. STATREPORTS, 2018, https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/(accessed 8 April 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract 2019; 36(9): 400–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopacz MS, Ames D, Koenig HG. It’s time to talk about physician burnout and moral injury. Lancet Psychiat 2019; 6(11): e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19, 2020, https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020(accessed 8 April 2020).

- 8.Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiat 2020; 7(4): e15–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy: ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1873–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2049–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage: allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1973–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiat 2020; 7(3): e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez PR, Lord H, Halcomb PE, et al. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud 2020; 111: 103637, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020748920301218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrlich H, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Protecting our healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med 2020; 8(7): 1527–1528. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32336585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond M, Liana W.Covid-19: Protecting frontline healthcare workers: what lessons can we learn from Ebola? BMJ 2020, https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/03/25/healthcare-workforce-safety-and-ebola-in-the-context-of-covid-19/(accessed 8 April 2020).

- 16.Bartzak PJ.Moral injury is the wound: PTSD is the manifestation. Medsurg Nurs 2015; 24(3): 10–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williamson V, Stevelink SAM, Greenberg N. Occupational moral injury and mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2018; 212(6): 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shay J. Casualties. Daedalus 2011; 140(3): 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meador KG, Nieuwsma JA. Moral injury: contextualized care. J Med Humanit 2018; 39(1): 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jameton A. Nursing practice, the ethical issues, vol. 22. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984, p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jameton A. Dilemmas of moral distress: moral responsibility and nursing practice. AWHONNS Clin Issue Perinat Women Healt Nurs 1993; 4(4): 542–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiinikka-Lydon J. Mapping moral injury: comparing discourses of moral harm. J Med Philos 2019; 44(2): 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev 2009; 29: 695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin BJ, Purcell N, Burkman K, et al. Moral injury: an integrative review. J Trauma Stress 2019; 32(3): 350–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil Med 2013; 178(6): 646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffman J, Liddell B, Bryant RA, et al. The relationship between moral injury appraisals, trauma exposure, and mental health in refugees. Depress Anxiety 2018; 35(11): 1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenig HG. Measuring symptoms of moral injury in veterans and active duty military with PTSD. Religions 2018; 9(3): 86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papazoglou K, Chopko B. The role of moral suffering (moral distress and moral injury) in police compassion fatigue and PTSD: an unexplored topic. Front Psychol 2017; 8: 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feinstein A, Pavisian B, Storm H. Journalists covering the refugee and migration crisis are affected by moral injury not PTSD. JRSM Open 2018; 9(3): 875901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray E, Krahé C, Goodsman D. Are medical students in prehospital care at risk of moral injury. Emerg Med J 2018; 35(10): 590–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray E. Moral injury and paramedic practice. J Paramed Pract 2019; 11(10): 424–425. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welsh DT, Ordóñez LD, Snyder DG, et al. The slippery slope: how small ethical transgressions pave the way for larger future transgressions. J Appl Psychol 2015; 100: 114–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenbrunsel AE, Messick DM. Ethical fading: the role of self-deception in unethical behavior. Soc Justice Res 2004; 17(2): 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asken MJ.Physician burnout: Moral injury is a questionable term. BMJ 2019; 365: l2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.*Glasberg A-L, Eriksson S, Norberg A. Factors associated with ‘stress of conscience’ in healthcare. Scand J Caring Sci 2008; 22(2): 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.*Gibbons SW, Shafer M, Hickling EJ, et al. How do deployed health care providers experience moral injury. Narrat Inq Bioeth 2013; 3(3): 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.*Simmons AM, Rivers FM, Gordon S, et al. The role of spirituality among military en route care nurses: source of strength or moral injury? Crit Care Nurse 2018; 38(2): 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.*Pavlish C, Brown-Saltzman K, Hersh M, et al. Nursing priorities, actions, and regrets for ethical situations in clinical practice. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011; 43(4): 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.*Choe K, Kang Y, Park Y. Moral distress in critical care nurses: a phenomenological study. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71(7): 1684–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.*Schrøder K, la Cour K, Jørgensen JS, et al. Guilt without fault: a qualitative study into the ethics of forgiveness after traumatic childbirth. Soc Sci Med 2017; 176: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.*Green J, Darbyshire P, Adams A, et al. It’s agony for us as well. Nurs Ethics 2016; 23(2): 176–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fry ST, Harvey RM, Hurley AC, et al. Development of a model of moral distress in military nursing. Nurs Ethics 2002; 9(4): 373–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross CA, Berry NS, Smye V, et al. A critical review of knowledge on nurses with problematic substance use: the need to move from individual blame to awareness of structural factors. Nurs Inq 2018; 25(2): e12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molendijk T. Toward an interdisciplinary conceptualization of moral injury: from unequivocal guilt and anger to moral conflict and disorientation. New Ideas Psychol 2018; 51: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fourie C. Moral distress and moral conflict in clinical ethics. Bioethics 2015; 29(2): 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarthy J, Gastmans C. Moral distress: a review of the argument-based nursing ethics literature. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22(1): 131–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh Y, Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: a quantitative literature review. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22(1): 15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aitamaa E, Suhonen R, Puukka P, et al. Ethical problems in nursing management: a cross-sectional survey about solving problems. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19(1): 417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laukkanen L, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H. Solving work-related ethical problems. Nurs Ethics 2016; 23(8): 838–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Myhre J, Saga S, Malmedal W, et al. Elder abuse and neglect: an overlooked patient safety issue: a focus group study of nursing home leaders’ perceptions of elder abuse and neglect. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20(1): 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkinson JM. Moral distress in nursing practice: experience and effect. Nurs Forum 1987; 23(1): 16–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tigard DW. Rethinking moral distress: conceptual demands for a troubling phenomenon affecting health care professionals. Med Health Care Philos 2018; 21(4): 479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corley MC. Nurse moral distress: a proposed theory and research agenda. Nurs Ethics 2002; 9(6): 636–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suhonen R, Stolt M, Habermann M, et al. Ethical elements in priority setting in nursing care: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud 2018; 88: 25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics 2009; 20(4): 330–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morley G, Bradbury-Jones C, Ives J. What is ‘moral distress’ in nursing? A feminist empirical bioethics study. Nurs Ethics 2020; 27(5): 1297–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Campbell SM, Ulrich CM, Grady C. A broader understanding of moral distress. Am J Bioeth 2016; 16(12): 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tigard DW. The positive value of moral distress. Bioethics 2019; 33(5): 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deschenes S, Gagnon M, Park T, et al. Moral distress: a concept clarification. Nurs Ethics 2020; 27(4): 1127–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rushton CH, Caldwell M, Kurtz M. CE: moral distress: a catalyst in building moral resilience. Am J Nurs 2016; 116(7): 40–49, https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2016/07000/CE__Moral_Distress__A_Catalyst_in_Building_Moral.25.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lachman VD. Moral resilience: managing and preventing moral distress and moral residue. Medsurg Nurs 2016; 25(2): 121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maiden J, Georges JM, Connelly CD. Moral distress, compassion fatigue, and perceptions about medication errors in certified critical care nurses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2011; 30(6): 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mason VM, Leslie G, Clark K, et al. Compassion fatigue, moral distress, and work engagement in surgical intensive care unit trauma nurses: a pilot study. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2014; 33(4): 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to Coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3(3): e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z, Ge J, Yang M, et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 88: 916–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nathaniel AK. Moral reckoning in nursing. West J Nurs Res 2006; 28(4): 419–438; discussion 439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCarthy J, Deady R. Moral distress reconsidered. Nurs Ethics 2008; 15(2): 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tigard DW. Moral distress as a symptom of dirty hands. Res Publica 2018; 25(3): 353–371. [Google Scholar]