Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

How accurately do women report a diagnosis of endometriosis on self-administered questionnaires?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Based on the analysis of four international cohorts, women self-report endometriosis fairly accurately with a > 70% confirmation for clinical and surgical records.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

The study of complex diseases requires large, diverse population-based samples, and endometriosis is no exception. Due to the difficulty of obtaining medical records for a condition that may have been diagnosed years earlier and for which there is no standardized documentation, reliance on self-report is necessary. Only a few studies have assessed the validity of self-reported endometriosis compared with medical records, with the observed confirmation ranging from 32% to 89%.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

We compared questionnaire-reported endometriosis with medical record notation among participants from the Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS; 1995-2013), Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (E3N; 1990-2006), Growing Up Today Study (GUTS; 2005–2016), and Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII; 1989–1993 first wave, 1995–2007 second wave).

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Participants who had reported endometriosis on self-administered questionnaires gave permission to procure and review their clinical, surgical, and pathology medical records, yielding records for 827 women: 225 (BWHS), 168 (E3N), 85 (GUTS), 132 (NHSII first wave), and 217 (NHSII second wave). We abstracted diagnosis confirmation as well as American Fertility Society (AFS) or revised American Society of Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) stage and visualized macro-presentation (e.g. superficial peritoneal, deep endometriosis, endometrioma). For each cohort, we calculated clinical reference to endometriosis, and surgical- and pathologic-confirmation proportions.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Confirmation was high—84% overall when combining clinical, surgical, and pathology records (ranging from 72% for BWHS to 95% for GUTS), suggesting that women accurately report if they are told by a physician that they have endometriosis. Among women with self-reported laparoscopic confirmation of their endometriosis diagnosis, confirmation of medical records was extremely high (97% overall, ranging from 95% for NHSII second wave to 100% for NHSII first wave). Importantly, only 42% of medical records included pathology reports, among which histologic confirmation ranged from 76% (GUTS) to 100% (NHSII first wave). Documentation of visualized endometriosis presentation was often absent, and details recorded were inconsistent. AFS or rASRM stage was documented in 44% of NHSII first wave, 13% of NHSII second wave, and 24% of GUTS surgical records. The presence/absence of deep endometriosis was rarely noted in the medical records.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

Medical record abstraction was conducted separately by cohort-specific investigators, potentially introducing misclassification due to variation in abstraction protocols and interpretation. Additionally, information on the presence/absence of AFS/rASRM stage, deep endometriosis, and histologic findings were not available for all four cohort studies.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Variation in access to care and differences in disease phenotypes and risk factor distributions among patients with endometriosis necessitates the use of large, diverse population samples to subdivide patients for risk factor, treatment response and discovery of long-term outcomes. Women self-report endometriosis with reasonable accuracy (>70%) and with exceptional accuracy when women are restricted to those who report that their endometriosis had been confirmed by laparoscopic surgery (>94%). Thus, relying on self-reported endometriosis in order to use larger sample sizes of patients with endometriosis appears to be valid, particularly when self-report of laparoscopic confirmation is used as the case definition. However, the paucity of data on histologic findings, AFS/rASRM stage, and endometriosis phenotypic characteristics suggests that a universal requirement for harmonized clinical and surgical data documentation is needed if we hope to obtain the relevant details for subgrouping patients with endometriosis.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This project was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development grants HD48544, HD52473, HD57210, and HD94842, National Cancer Institute grants CA50385, R01CA058420, UM1CA164974, and U01CA176726, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant U01HL154386. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. AS, SM, and KT were additionally supported by the J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation. MK was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Programme (#PIOF-GA-2011-302078) and is grateful to the Philippe Foundation and the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation for their financial support. Funders had no role in the study design, conduct of the study or data analysis, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. LA Wise has served as a fibroid consultant for AbbVie, Inc for the last three years and has received in-kind donations (e.g. home pregnancy tests) from Swiss Precision Diagnostics, Sandstone Diagnostics, Kindara.com, and FertilityFriend.com for the PRESTO cohort. SA Missmer serves as an advisory board member for AbbVie and a single working group service for Roche; neither are related to this study. No other authors have a conflict of interest to report. Funders had no role in the study design, conduct of the study or data analysis, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: validation, endometriosis, cohort, population studies, data harmonization, self-report

Introduction

Endometriosis, in which endometrial-like tissue is found outside of the uterus, affects approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women and can lead to debilitating pelvic pain, diminished quality of life, infertility, and significant health care costs (Missmer et al., 2004; Shafrir et al., 2018; Zondervan et al., 2018; Ghiasi et al., 2020). It is a heterogeneous disease in terms of lesion characteristics, symptom presentation, and response to treatment (Zondervan et al., 2020). As such, studies with large sample sizes that include diverse populations are needed to identify and adequately analyze informative endometriosis subgroups. Grouping all endometriosis participants into one category may bias estimates towards the null if some subgroups but not others are associated with certain risk factors or with predicting treatment responses.

Currently, definitive diagnosis of endometriosis requires surgical visualization, with some arguing for the additional requirement of histologic confirmation of endometrial glands and/or stroma in at least one excised lesion (Agarwal et al., 2019). Thus, many studies rely on medical record abstraction. However, conducting medical record abstraction in large epidemiologic studies can be costly and time-consuming while still yielding inconsistent information (Becker et al., 2014; Vitonis et al., 2014). Consequently, many studies include small samples from single clinical sites that may provide care to biased subsets of the general population of women at risk for endometriosis. Indeed, the prevalence of endometriosis alone may differ by an order of magnitude when comparing specialty clinic populations to general populations (Ghiasi et al., 2020). Additionally, analyses of insurance claims data (e.g. International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes), which capture a more comprehensive population, are limited to patients who received an ICD-10 code for billing purposes and have been shown to inadequately capture the full extent of endometriosis disease (Whitaker et al., 2019). For example, endometriosis remains coded within ‘non-inflammatory disorders of female genital tract,’ which is entirely inconsistent with current knowledge, and thus may be overlooked. In addition, there is no coding option to define endometriosis subgroups such as superficial or deep disease (Whitaker et al., 2019).

Currently, overcoming these limitations requires reliance on self-reported endometriosis via self-administered questionnaires. To date, only a few studies have assessed the validity of self-reported endometriosis, finding a wide range of validation proportions—32–89%––across different populations and using different data sources (e.g. medical records and inpatient hospital registries) as the gold standard for confirmation (Treloar et al., 2000; Missmer et al., 2004; Saha et al., 2015, 2017). No study has compared the validity of self-reported endometriosis against medical records across populations that differ with respect to age and race/ethnicity.

Therefore, we compared endometriosis diagnoses reported via self-administered questionnaires to medical record notation across four diverse cohorts. We also assessed the availability of endometriosis phenotypic details, including American Fertility Society (AFS) or revised American Society of Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) stage and visualized macro-presentation of endometriosis lesions (e.g. superficial peritoneal, endometrioma, deep endometriosis).

Materials and methods

Participant populations

To assess the validity of self-reported endometriosis, medical records were obtained for participants of the following four cohorts who had reported endometriosis on self-administered questionnaires: the Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS), Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (E3N)––often referred to in the USA as the ‘French Teachers’ Cohort’, Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), and Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII). In all four cohorts, women (or a subset of women as described below and in Table I) who reported an endometriosis diagnosis on a self-administered questionnaire (see Supplementary Data for cohort-specific questions) were contacted by cohort staff to confirm their report and to provide consent to release pertinent medical records. We evaluated the accuracy of reporting ‘Yes’ to having been diagnosed with endometriosis. No cohort attempted to collect medical records from participants who never reported that they had been diagnosed with endometriosis, although all cohorts asked the participants repeatedly at an interval of a minimum of every 2 years whether they had been diagnosed with endometriosis. None of the cohorts included a question on undergoing a laparoscopy or laparotomy except for in the context of confirmation of endometriosis by laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, it would be logistically and financially infeasible to obtain medical records to validate ‘never’ report of endometriosis among the full cohorts.

Table I.

Population characteristics and validation study eligibility of the Black Women’s Health Study, Etude Epidémiologique aupres de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale d l’Education Nationale, Growing Up Today Study, and Nurses’ Health Study II.

| BWHS | E3N | GUTS |

NHSII

first wave |

NHSII

second wave |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment years | 1995 | 1989–1991 | 1996 & 2004 | 1989 | 1989 |

| Age range at baseline (yrs) | 21–69 | 39–66 | 9–17 | 25–42 | 25–42 |

| Baseline population (N) | 59,001 | 98,995 | 15,044 | 116,429 | 116,429 |

| Post-high school education (%) | 83% | 87% | 98% | 100% | 100% |

| Questionnaire cycles of endometriosis self-report | 1995–2013 | 1990–2005 | 2005–2016 | 1989–1993 | 1989–2007 |

| Total self-reported endometriosis cases (N) | 1,605 | 2,104 | 491 | 1,766 | 9,452 |

| Endometriosis case type for validation1 | Incident | Incident | Incident & prevalent | Incident | Incident & prevalent |

| Eligible endometriosis cases (N)2 | 1,605 | 558 | 491 | 1,766 | 711 |

| Endometriosis cases selected for validation study (N) | 1,605 | 200 | 380 | 200 | 711 |

BWHS, Black Women’s Health Study; E3N, Etude Epidémiologique aupres de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale d l’Education Nationale; GUTS, Growing Up Today Study; NHSII, Nurses’ Health Study II.

Participants were considered to have prevalent endometriosis if they reported their endometriosis had been diagnosed before baseline. Incident endometriosis cases were diagnosed after baseline.

Number of self-reported endometriosis cases eligible for inclusion in the cohort's case validation study.

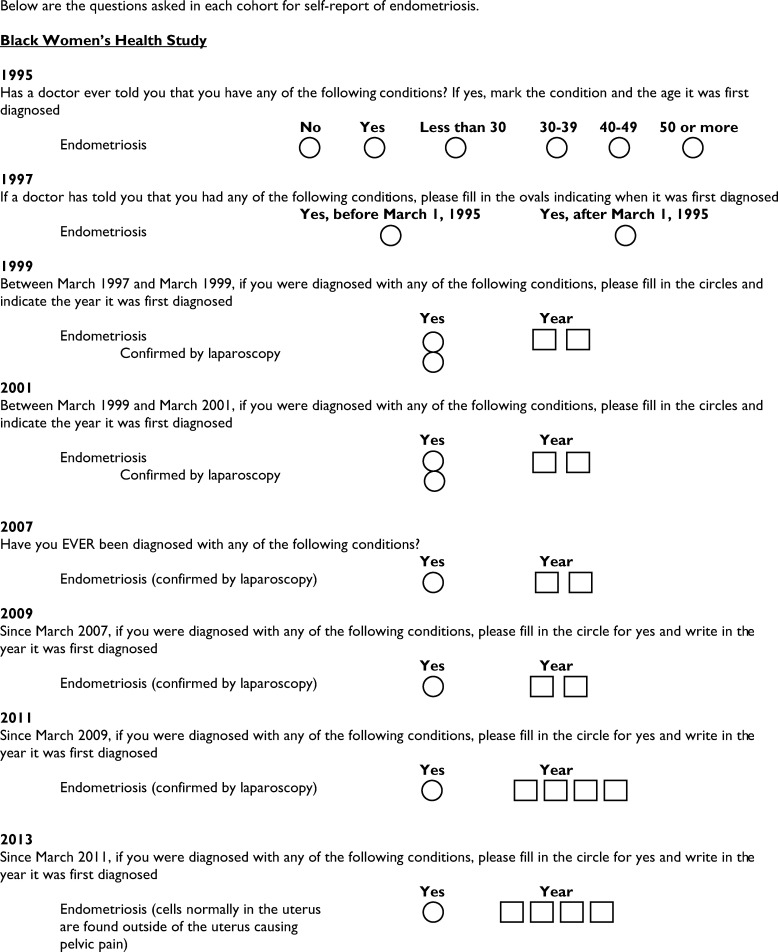

Black Women’s Health Study

The BWHS is an ongoing, prospective cohort study that began in 1995 when 59,001 self-identified black women aged 21–69 years living within the USA were recruited from the subscription list of Essence magazine and black professional organizations (Rosenberg et al., 1995; Russell et al., 2001). At baseline, participants completed self-administered postal questionnaires to collect data on demographic, lifestyle, and behavioral factors; reproductive and medical history; and medication use. Participants then completed follow-up questionnaires every 2 years following enrollment to update outcome, exposure, and covariate data. From 1995 onward, participants were asked to report any diagnosis of endometriosis. From 1999 onward, participants who reported an endometriosis diagnosis were additionally asked about confirmation by laparoscopic surgery. From 2008 through 2016, all participants of reproductive age who reported an incident diagnosis of endometriosis between baseline (1995) and 2013 (n = 1605) were re-contacted to confirm their diagnosis and to consent for study staff to procure portions of their medical record pertinent to endometriosis and its diagnosis. For participants who provided consent for procurement and review of their medical record, study staff attempted to contact the treating physician and/or hospital to obtain all relevant medical records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Campus.

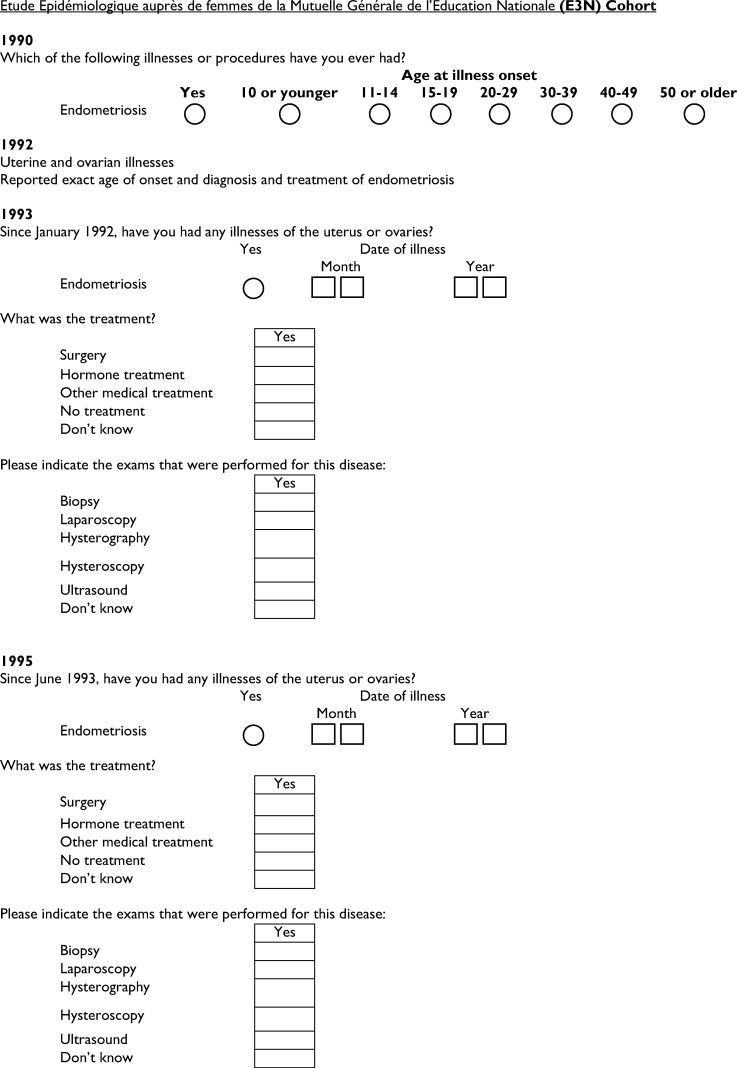

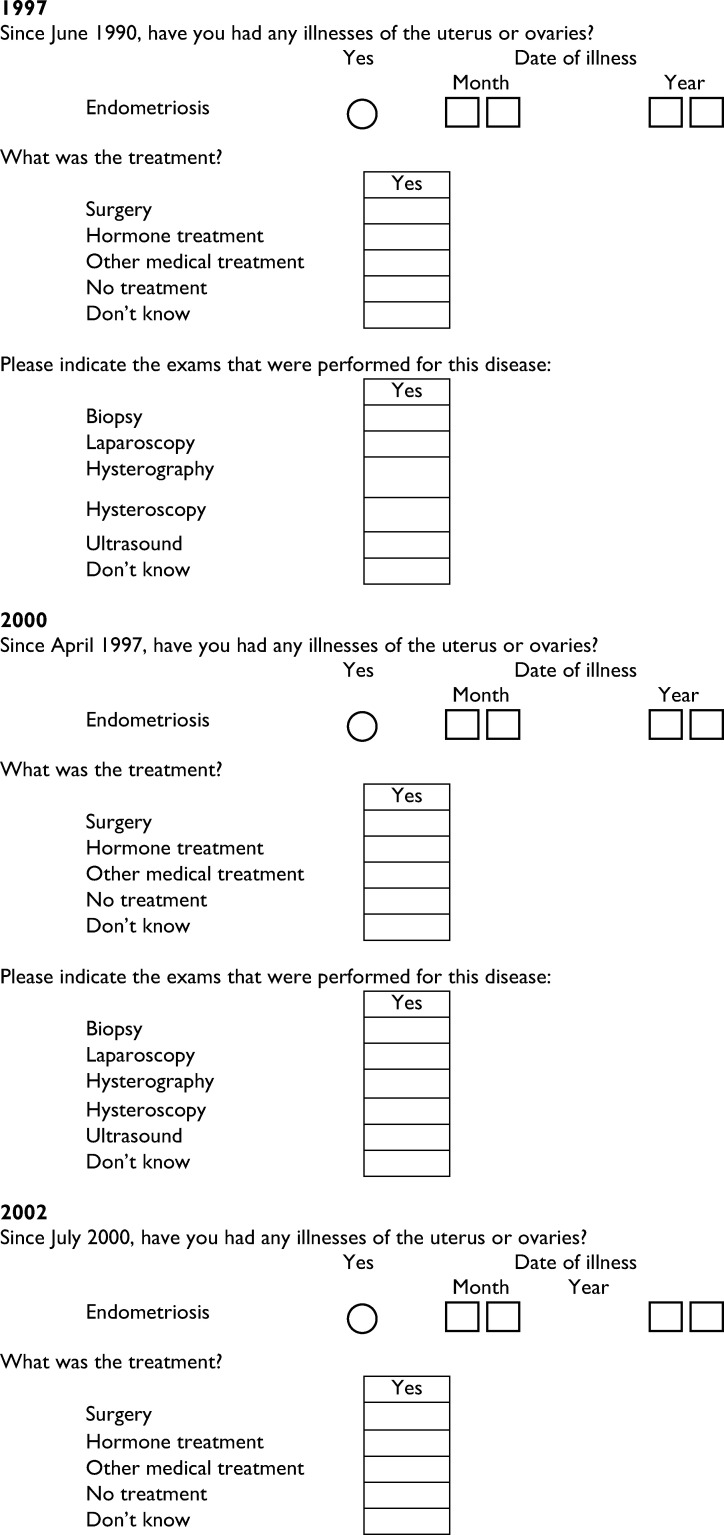

Etude Epidémiologique auprès de femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale

The E3N study is a French prospective cohort study involving 98,995 French women born between 1925 and 1950 and insured by a national health plan primarily covering teachers (Clavel-Chapelon and E3N Study Group, 2015). Participants were enrolled from February 1, 1989 through November 30, 1991 after returning a self-administered questionnaire on lifestyle and medical history and a signed consent form. Follow-up questionnaires are sent every 2–3 years to update lifestyle and medical information. In 1992, when these women were age 42 to 67 years, participants reported if they had ever been diagnosed with endometriosis; information on endometriosis diagnosis was updated at each subsequent questionnaire cycle through 2008. Between 1990 and 2005, 558 participants reported that they had an incident endometriosis diagnosis, and in 2006, 200 of these participants were randomly selected to confirm their diagnosis and to provide their hospital and pathology records related to endometriosis, along with the contact details of their physicians. A participant’s physician was contacted if the participant could not find her medical records or questions arose while abstracting from the medical records received to seek a definitive confirmation. The E3N cohort received ethical approval for the study from the French National Committee for Computerized Data and Individual Freedom (Comité National Informatique et Libertés, CNIL).

Nurses’ Health Study II

The NHSII is an ongoing, prospective cohort study. A total of 116,429 women aged 25–42 years and living in one of 14 states in the USA were enrolled in 1989—all were registered nurses. Through self-administered questionnaires, participants provided information on demographic, lifestyle, anthropometric, reproductive, and medical factors at baseline and biennially. Starting in 1993, participants were asked to report on each questionnaire if they had been diagnosed with endometriosis and whether that diagnosis was confirmed by laparoscopy. Two endometriosis validation studies within the NHSII have been performed. In the first wave in 1994, a random sample of 200 women from the 1,766 who had self-reported an incident diagnosis of endometriosis between 1989 and 1993 were contacted to confirm their report and consent to procurement of their pertinent medical records for review (Missmer et al., 2004). In the second wave, from 2009 through 2011, all participants who reported a diagnosis of endometriosis between 1989 and 2007, were not part of the first validation study, and were members of the NHSII nested blood sample cohort (n =711) (Tworoger et al., 2006) were contacted to confirm their endometriosis diagnosis and consent to procurement of the pertinent portions of their medical records for review. The relevant physicians and/or hospitals were contacted to obtain these medical records. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Growing Up Today Study

GUTS is an ongoing, prospective cohort of 27,706 women and men (n =15,044 women) living in the USA. The first stage of the cohort (GUTS1) began in 1996 with the recruitment of girls and boys, then aged 9–14 years, who are children of women in NHSII. In 2004, a second group of GUTS participants, then aged 10–17 years, were also enrolled (GUTS2). All participants completed baseline questionnaires and annual or biennial follow-up questionnaires on demographics, lifestyle factors, and reproductive and medical history. Starting in 2005, female participants were asked to report on each questionnaire if they had been diagnosed with endometriosis and if their diagnosis was confirmed by laparoscopy. All participants who had reported ever being diagnosed with endometriosis on questionnaires between 2005 and 2016 were contacted to confirm their diagnosis and obtain consent to procure the pertinent portions of their medical records for review (n =380). The relevant physicians and/or hospitals were contacted to obtain these medical records. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Medical record abstraction

For all four cohorts, cohort-specific trained investigators and/or physicians abstracted information about endometriosis from the medical records using standardized forms designed for and specific to each cohort. For the validation component, these standardized forms captured: if the medical records received were missing records deemed relevant to endometriosis (e.g. no information from a primary care physician, surgeon, or gynecologist; no information on gynecologic conditions or review of gynecologic issues); evidence of surgery for suspected endometriosis; noted visualization of endometriosis at surgery; and availability of pathology report findings. Endometriosis reported on the self-administered questionnaire was classified as confirmed if documentation of endometriosis was found in any of the physician, surgical, or pathology records. Participants were further classified according to the source of endometriosis documentation. Participants were classified as having a clinical diagnosis of endometriosis if there was documentation of a physician diagnosis of endometriosis without evidence of a surgical evaluation. Surgically confirmed endometriosis was noted if there was evidence of a surgical evaluation and a report that a surgeon had visualized endometriosis during a laparoscopy, laparotomy, or hysterectomy (regardless of surgical modality). If a pathology report was available, documentation of endometriosis and/or the identification of endometrium-like glands or stroma were classified as histologically confirmed endometriosis. Participants for whom endometriosis was not noted as having been visualized during surgery but for whom the pathology report documented endometriosis were also classified as histologically confirmed, but it was noted that endometriosis had been erroneously absent from the surgical record. In the first and second NHSII waves and GUTS, additional information on AFS (The American Fertility Society, 1979, 1985) or rASRM (American Society for Reproductive Medicine, 1997) stage and the presence or absence of endometrioma(s) or deep endometriosis (NHSII second wave and GUTS only) were also abstracted.

Statistical analyses

For each cohort, we calculated overall confirmation of self-reported endometriosis (i.e. positive predictive value) as the proportion of participants with any medical record documentation of endometriosis (i.e. those with a clinical, surgical, or histologic diagnosis) divided by the total number of participants for whom relevant medical records were obtained. Additionally, we assessed the proportion of participants with surgical confirmation and the proportion with histologically confirmed endometriosis out of participants with surgical and/or pathology records available. Finally, we calculated the proportion of participants with clinical confirmation (i.e. a clinician had told them they have endometriosis) out of participants without evidence of surgery. In secondary analyses within BWHS, GUTS, and NHSII, we assessed the surgical and physician confirmation proportions separately for those who reported that they had laparoscopic confirmation of endometriosis and those who did not report that their diagnosis had included laparoscopic confirmation. Additionally, in NHSII second wave, we assessed the overall and surgical confirmation proportions separately for those with concurrent infertility and those who never reported infertility, as we hypothesized a priori that women with concurrent infertility may recall their endometriosis diagnosis more accurately than women who never experienced infertility. Concurrent infertility included women who reported undergoing an infertility evaluation in the same follow-up cycle as their self-reported endometriosis diagnosis. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The proportion of cohort participants who did not respond to mailings or had an undeliverable address ranged from 8% for NHSII first wave to 70% for BWHS (Table II). Among those contacted, 12.5% (BWHS), 16.8% (GUTS), 1.5% (NHSII first wave), and 10.8% (NHSII second wave) denied their original report of an endometriosis diagnosis. These data were not available for the E3N cohort. Of those who were contacted and did not deny their original report of an endometriosis diagnosis, 19.7% (BWHS), 91.5% (E3N), 36.7% (GUTS), 75.6% (NHSII first wave), and 56.8% (NHSII 2 wave) provided permission to obtain their medical records for review.

Table II.

Physician, surgical, and pathology record receipt and confirmation proportions by cohort.

| Cohort | BWHS | E3N | GUTS |

NHSII

first wave |

NHSII

second wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline population | 59 001 | 98 995 | 15 044 | 116 429 | 116 429 |

| Years in which endometriosis was self-reported | 1995–2013 | 1990–2005 | 2005–2016 | 1989–1993 | 1989–2007 |

| Years when participants were contacted for validation | 2008–2016 | 2007 | 2011–2017 | 1996 | 2009–2011 |

| Eligible women who self-reported endometriosis (N) | 1605 | 558 | 491 | 1766 | 711 |

| Contacted for medical record review (N) | 1605 | 200 | 380 | 200 | 711 |

| Unable to contact/never responded1 | 1128 | — | 139 | 16 | 169 |

| Denied diagnosis on consent form | 200 | — | 64 | 3 | 77 |

| Confirmed diagnosis but not access to medical records2 | — | — | 61 | 32 | 15 |

| Permission obtained to review medical records3 | 277 (19.7%) | 183 (91.5%) | 116 (36.7%) | 149 (75.6%) | 360 (56.8%) |

| Medical records never received | 52 | 0 | 27 | 17 | 132 |

| Inadequate information received4 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 0 | 11 |

| Relevant medical records received and reviewed | 225/277 (81.2%) | 168/183 (91.8%) | 85/116 (73.3%) | 132/149 (88.6%) | 217/360 (60.3%) |

| Found no clinical diagnosis and no surgery performed | 18 | — | 4 | 12 | 3 |

| Clinical diagnosis noted but no surgery performed5 | 28 | — | 16 | 14 | 4 |

| Surgically confirmed | 134 | 137 | 63 | 98 | 185 |

| Clinical diagnosis noted but disconfirmed at surgery6 | 0 | — | 2 | 8 | 2 |

| Found no clinical diagnosis and disconfirmed at surgery | 45 | — | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Pathology-confirmed but not visualized at surgery | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Pathology-confirmed but no surgical report obtained | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Overall confirmation proportion 7 | 162/225 (72.0%) | 137/168 (81.5%) | 81/85 (95.3%) | 112/132 (84.8%) | 206/217 (94.9%) |

| Surgically confirmed proportion8 | 134/179 (74.9%) | 137/168 (81.5%) | 63/65 (96.9%) | 98/106 (92.5%) | 185/204 (90.7%) |

| Clinically confirmed proportion9 | 18/28 (64.3%) | — | 16/20 (80.0%) | 14/26 (53.8%) | 4/7 (57.1%) |

Number of participants we were either unable to contact or never responded to repeated mailings.

These participants confirmed their endometriosis diagnosis but either denied access to their medical records or did not respond to requests for access.

The percentage providing permission to obtain medical records was calculated out of the total contacted minus those who denied their endometriosis diagnosis.

Reasons inadequate information was received for medical records included no information on disease history and symptoms or medical records not relating to primary care physician, surgeon or gynecologic visits.

Evidence found in the medical records that the participant had been told by her clinician that she most likely had endometriosis but no evidence that she ever had surgery to confirm her diagnosis.

The eight surgically disconfirmed endometriosis cases in the NHSII first wave were all clinically confirmed (found documentation that the woman was told by her clinician that she most likely had endometriosis) and included in the overall and the clinically confirmed proportion.

The numerator of this measure includes those who were surgically confirmed and clinically confirmed.

The denominator of this measure includes those who had evidence of surgery in their medical records.

The denominator of this measure includes those who did not have evidence of surgery in their medical records.

Among those who confirmed their diagnosis and consented to records procurement, relevant medical records were obtained and reviewed for 827 women: n =225 (BWHS), 168 (E3N), 85 (GUTS), 132 (NHSII first wave), and 217 (NHSII second wave) (Table II). We excluded 30 participants for having irrelevant medical records, as the only documents we received were unrelated to either primary care physician, surgical, or gynecologic visits. In the NHSII second wave, 211 participants had information to inform their surgical confirmation; for six individuals a pathology report but no surgical report could be procured. We noted that all six of these participants had documentation in their pathology reports of histologically confirmed endometriosis.

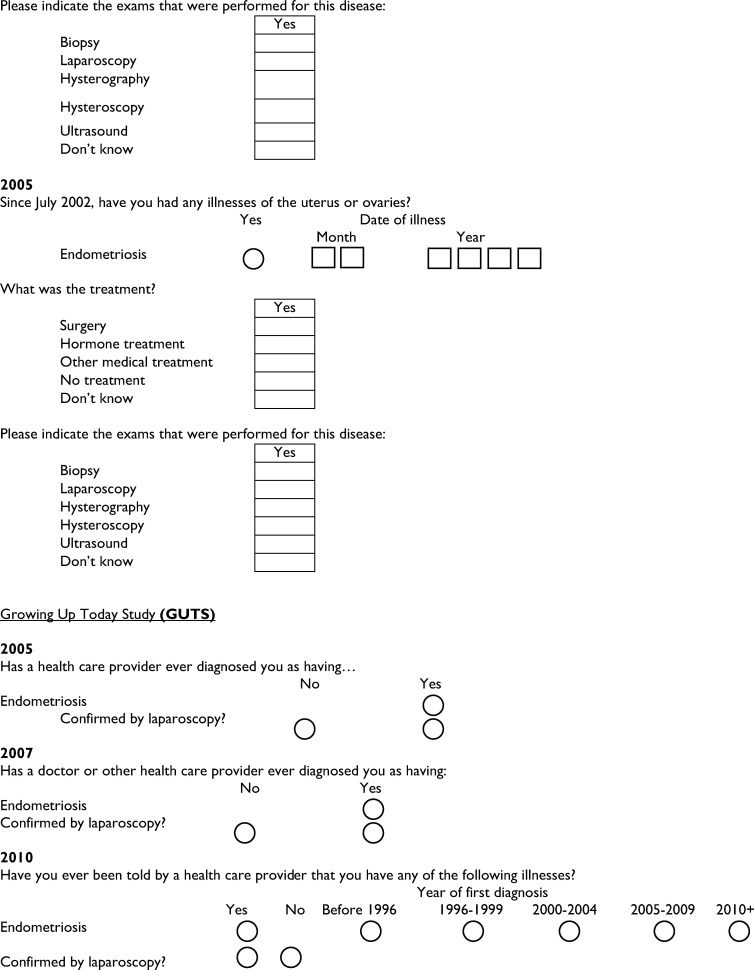

Among those for whom relevant medical records were reviewed, the overall confirmation proportion of self-reported endometriosis diagnosis was 84.4% (698/827), ranging from 72% for BWHS to 95% for GUTS (Table II). A pathology report was available for only 42% of surgeries (Fig. 1). Among participants with surgically confirmed endometriosis, the overall histologic confirmation proportion was 92% (133/145) and ranged from 76% for GUTS to 100% for NHSII first wave (data not shown). When validation was restricted to those who self-reported a laparoscopic confirmation of their diagnosis, the overall confirmation proportion rose to 97% (367/379), ranging from 95% for NHSII second wave to 100% for NHSII first wave (Table III). Among participants for whom endometriosis was suspected prior to surgery but not visualized at surgery (surgically disconfirmed endometriosis), there was often documentation of other conditions, such as uterine fibroids or endometrial polyps, that are associated with symptoms common among women with endometriosis (e.g. chronic pelvic pain), as opposed to having no evidence of pathologic disorders (data not shown).

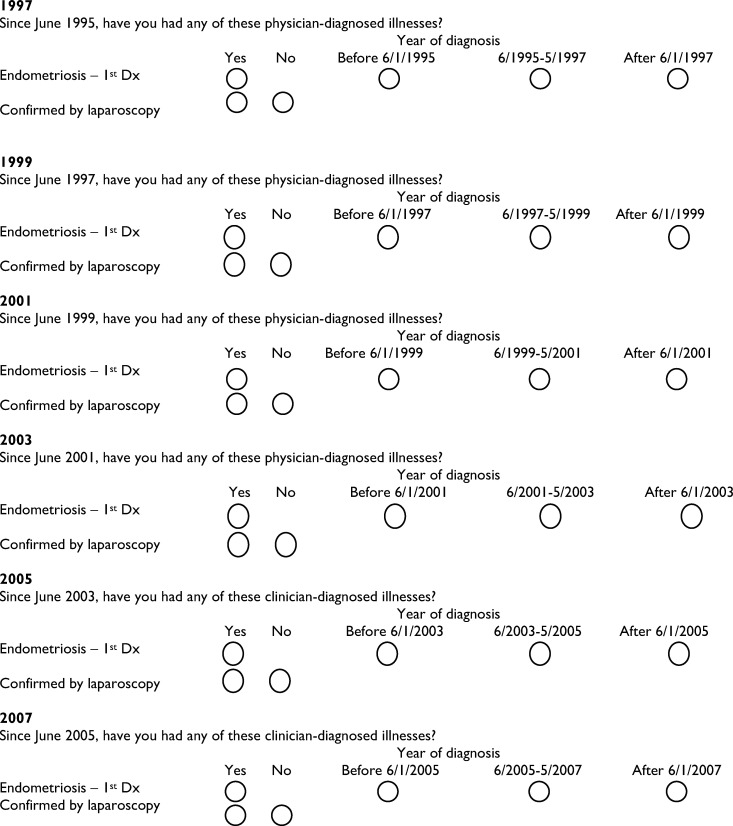

Figure 1.

Availability of histologic, AFS/rASRM stage, and endometriosis phenotypic characteristics from medical records. Percentage of Nurses’ Health Study II 1st and second wave (NHSII W1 and NHSII W2) and Growing Up Today Study (GUTS) participants with surgically confirmed endometriosis who had a pathology report or information within the surgical record noting: American Fertility Society (AFS) or revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) stage; presence or absence of deep endometriosis; or presence or absence of endometrioma.

Table III.

Differences in surgical and physician confirmation proportions by self-reported laparoscopic confirmation.1

| Cohort | GUTS |

NHSII

first wave |

NHSII

second wave |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Laparoscopic Confirmation | |||

| Medical records received and reviewed (N) | 64 | 105 | 210 |

| Found no clinical diagnosis and no surgery performed | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Clinical diagnosis noted but no surgery performed2 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Surgically confirmed | 59 | 97 | 180 |

| Clinical diagnosis noted but disconfirmed at surgery3 | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Found no clinical diagnosis and disconfirmed at surgery | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Pathology-confirmed but not visualized at surgery | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Pathology-confirmed but no surgical report obtained | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Overall confirmation proportion 4 | 63/64 (98.4%) | 105/105 (100%) | 199/210 (94.8%) |

| Surgically confirmed proportion5 | 59/60 (98.3%) | 97/105 (92.4%) | 180/199 (90.5%) |

| Clinically confirmed proportion6 | 3/4 (75.0%) | — | 3/6 (50.0%) |

| Did Not Report Laparoscopic Confirmation 7 | |||

| Medical records received and reviewed (N) | 20 | 27 | 7 |

| Found no clinical diagnosis and no surgery performed | 3 | 12 | 0 |

| Clinical diagnosis noted but no surgery performed2 | 13 | 14 | 1 |

| Surgically confirmed | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Clinical diagnosis noted but disconfirmed at surgery | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Found no clinical diagnosis and disconfirmed at surgery | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pathology-confirmed but not visualized at surgery | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pathology-confirmed but no surgical report obtained | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Overall confirmation proportion | 17/20 (85.0%) | 15/27 (55.6%) | 7/7 (100%) |

| Surgically confirmed proportion5,8 | 3/4 (75.0%) | 1/1 (100%) | 5/5 (100%) |

| Clinically confirmed proportion6 | 13/16 (81.3%) | 14/26 (53.8%) | 1/1 (100%) |

Participants who reported laparoscopic confirmation of their endometriosis diagnosis on self-administered questionnaires.

Evidence in the medical records that the participant had been told by her clinician that she most likely had endometriosis but no evidence that she ever had surgery to confirm her diagnosis.

The eight surgically disconfirmed cases in the NHSII first wave were all clinically confirmed (found documentation that the woman was told by her clinician that she most likely had endometriosis) and included in the physician confirmation proportion.

The numerator of this measure included those who were surgically confirmed and clinically confirmed.

The denominator of this measure includes those who had evidence of surgery in their medical records.

The denominator of this measure includes those who did not have evidence of surgery in their medical records.

Total N does not add up to 21 for GUTS as one participant was missing laparoscopic confirmation status self-report and therefore could not be stratified.

Evidence of surgery was found for 11 of the participants who did not self-report having had a laparoscopic confirmation. For the one participant from NHSII first wave and five participants from NHSII second wave, all had hysterectomies at which the presence of endometriosis was documented. For the four GUTS participants, three of them had self-reported a clinical diagnosis that preceded the data of the medical record documentation of laparoscopic surgery and one had a tubal ligation during which endometriosis was visualized.

In secondary analyses, among participants who did not self-report a laparoscopic confirmation in the NHSII and GUTS, the overall confirmation proportion varied substantially among cohorts—ranging from 56% in NHSII first wave to 100% in NHSII second wave—although these estimates were based on small sample sizes (Table III). Among the women who did not self-report a laparoscopic confirmation but were found to have a report of surgically visualized endometriosis within their medical records, six had a hysterectomy (NHSII) and the remaining four (GUTS) received a clinical diagnosis before their laparoscopic surgery. In the BWHS, confirmation proportions were somewhat higher among women who had reported laparoscopic confirmation on their questionnaire—74.8% (134 of 179)––as compared with those who had not reported laparoscopic confirmation—61.8% (28 of 46) (data not shown). However, the first two (1995 and 1997) BWHS questionnaires did not ask about laparoscopic confirmation of endometriosis; therefore, some of those in the group who had not reported laparoscopic confirmation would probably have reported laparoscopic confirmation if asked, thereby raising the first proportion and lowering the second. The overall confirmation proportion did not vary between NHSII second wave participants who were never infertile (94.9%) compared with those who concurrently reported infertility and an endometriosis diagnosis (95.2%; Supplementary Table SI). However, the surgical confirmation proportion was higher in the concurrent infertile group (98%) compared with the never infertile group (89%).

For GUTS and NHSII 1st and second waves, attempts for abstraction of details on stage (AFS or rASRM when available), histologic findings, and visualized endometriosis macro-phenotypic presentation (endometrioma(s) and deep endometriosis) from the medical records showed that this information was most often absent (Fig. 1). The proportion of medical records among participants with surgically confirmed endometriosis and any stage information varied from 13% in NHSII second wave to 44% in NHSII first wave. Only 3% of NHSII second wave and 6% of GUTS records mentioned the presence or absence of deep endometriosis among participants with surgically confirmed endometriosis.

Discussion

Although large sample sizes of women with endometriosis are needed in order to fully investigate the heterogeneity of endometriosis in relation to risk factors and response to treatments, the majority of large studies rely on self-report of endometriosis diagnosis from self-administered questionnaires, the accuracy of which has not been fully investigated. Our results indicated that women report endometriosis fairly well, with an overall confirmation proportion of 84% (ranging from 72% to 95% among cohorts), indicating that if a participant reported being told by a physician that she had endometriosis, she reliably reported that information. Women who reported that their endometriosis diagnosis was confirmed by laparoscopic surgery had an exceptionally high overall confirmation proportion of over 94%. Confirmation of endometriosis diagnosis did not substantially vary by infertility status at the time of endometriosis self-report. Information on pathology results, AFS or rASRM stage, and the presence or absence of deep endometriosis or endometrioma(s) were often absent from the medical records reviewed.

For the purposes of the present study, the overarching goal was to determine validity of endometriosis case status via self-administered questionnaire in large, diverse populations. Thus, although there is debate about the requirement of surgical visualization with and without pathology confirmation for ‘true’ endometriosis diagnosis (Agarwal et al., 2019), we deemed that if a physician had noted in the clinical record that this patient likely had endometriosis, it is reasonable to believe that, when asked, that woman would indeed report that she had been told by a physician that she had endometriosis.

Previous studies on the validity of self-reported endometriosis have observed varying confirmation proportions, ranging from 32% to 89% (Treloar et al., 2000; Missmer et al., 2004; Saha et al., 2015, 2017). These variations in confirmation proportions could be due to: differences in the definition of a confirmed case (e.g. surgical with and without pathologic confirmation versus clinical); different population groups (e.g. health professionals versus general population); differences in methods for confirming endometriosis (e.g. registries versus medical records); and differences in how questions about self-reported endometriosis were asked (e.g. confirmation by laparoscopic surgery). Saha et al., (2015) reported a confirmation proportion for endometriosis of 82%, which included surgical, histologic and/or clinical medical record evidence within two large Swedish twin cohorts. Within the same twin cohorts, Saha et al., (2017) observed a confirmation proportion of only 32% when comparing self-reported endometriosis to Swedish inpatient registry data. This discrepancy highlights that the choice of the gold standard confirming endometriosis and the definition of a confirmed endometriosis case can dramatically alter findings.

Within our study, we observed a fairly wide range of overall confirmation proportions, potentially due to differences in the populations of the four cohort studies. BWHS, a cohort of women from the general US population (aged 21–69 years at enrollment), had the lowest overall confirmation proportion (72%), whereas GUTS, a cohort of children of registered nurses (aged 9–17 years at enrollment), had the highest overall confirmation proportion (95%). The overall confirmation proportion in the E3N, a cohort of women from the general French population (aged 39–66 years at enrollment), was fairly high (82%). This may be due to differences in access to medical records between the US and French populations, as French participants possessed and provided their own medical records, whereas almost all US participant records had to be obtained from a healthcare provider. These results suggest that consideration of the accuracy of self-reported endometriosis should depend on the context/population within which the study is conducted, and therefore should inform the level of detail and format for the wording of questions to maximize validity.

We additionally aimed to capture information on histologic confirmation. Often reviewers and readers of endometriosis scientific papers assume that histologic information is or should be readily available. This study reinforces that that is not the case in the USA. Less than half of the GUTS and NHSII 1st and second wave participants had a relevant pathology report from which we could assess histologic confirmation. For those who did have a pathology report, additional challenges arose in abstracting information on pathology findings including: most often only a single index lesion was sent to pathology; and lack of evidence of assessment for endometriosis by the pathologist, particularly during a hysterectomy, for an indication other than endometriosis. For example, one NHSII second wave participant had surgery with a suspected endometrioma sent to pathology, which was determined to be an inclusion cyst by the pathologist. However, the surgical report documented visualization of additional lesions believed to be superficial peritoneal endometriotic implants—none of which were sent to pathology. Thus, the participant must remain—perhaps erroneously—classified as surgically but not histologically confirmed. With the paucity of pathology reports and the lack of physicians sending appropriate lesion biopsies to pathologists, caution should be used when abstracting histologic confirmation from medical records and by overemphasis of diagnostic criteria that are not widely standard of clinical care.

Although we found that women self-reported their endometriosis diagnosis fairly well, there are ways in which self-report could be improved. Among some of the cohorts studied, approximately 10-17% of participants contacted denied their initial self-report upon re-contact. It may have been that at the time of completing a given questionnaire, they believed they had endometriosis and later learned this was not the case, or it could simply be that an incorrect box was checked on that questionnaire. Therefore, re-contacting the participant to confirm self-report could help to improve the accuracy of initial self-reports. Additionally, the overall confirmation proportion was higher among women reporting laparoscopic confirmation of their endometriosis diagnosis compared with those not reporting laparoscopic confirmation. This may be driven by the number and clarity of discussions between a patient and practitioner when choosing to undergo laparoscopy and subsequently reviewing the results. The addition of a question about whether an endometriosis diagnosis was confirmed by laparoscopic surgery would help to subset participants with the most accurate reporting of endometriosis.

Information on AFS or rASRM stage was highly variable in medical records from NHSII 1st and second waves and GUTS. Although 44% of NHSII first wave medical records included information on stage, only 13% of NHSII second wave and 24% of GUTS included stage information. The majority of reports indicated stage either numerically (e.g. Stage III) or qualitatively (e.g. mild-to-moderate stage) with very few reports listing out the actual score. The presence or absence of deep endometriosis was also rarely documented. Interestingly, among surgically confirmed cases, a higher proportion of GUTS (6%) as compared to NHSII second wave (3%) medical records reported deep endometriosis; the opposite of what we would expect, given the age distribution of the two cohorts. However, the GUTS cases were evaluated for endometriosis during a time period (1996-2016) when surgeons and radiologists or other imaging specialists have been more thoroughly assessing for deep endometriosis as compared to the time period when NHSII second wave cases (1972-2008) were diagnosed. These results highlight the existing limitations of using medical records to abstract information on surgical information relevant for subgrouping endometriosis cases.

The presence of an endometrioma was reported in almost 30% of NHSII second wave medical records; aligning with the expected 20-40% of endometriosis patients who will have at least one endometrioma. However, the presence of an endometrioma was reported in only 8% of GUTS medical records, potentially due to the younger age at diagnosis for GUTS compared to NHSII participants. Accurate reporting of endometriomas in medical records is crucial for appropriate subgrouping of endometriosis patients as the presence of an endometrioma contributes to the rASRM categorization of stage III or IV disease, which have been more strongly associated with genomic loci compared to stage I and II disease (Sapkota et al., 2015). Additionally, endometriomas may be an important subgroup potentially contributing to the risk of ovarian cancer among women with endometriosis (Saavalainen et al., 2018), and lack of information on the endometriosis subtypes will make it impossible to rigorously explore these associations.

The lack of information on histologic confirmation, AFS or rASRM stage, and endometriosis macro-phenotypes calls into question the feasibility of using medical records for abstracting subtyping information and may yield biased data when analyses are restricted to only those records that do include this information. Furthermore, the lack of consistency in the information documented additionally hampers discovery. Without required, standardized documentation tools, medical records are subject to recording bias due to: time pressures placed on physicians limiting the amount of information they record; variations in how well physicians document the full medical history of their patients; and correlation with the intensity of specialization or personal interest of the physician (Luck et al., 2000). Luck et al., (2000) used patient ‘actors’ with four different medical conditions to assess how well the quality of care received by the patients was reflected in the medical records. Using standardized checklists filled out by the patients (gold standard) and chart abstraction of visits with the physicians, the authors found a sensitivity of only 70% and specificity of 81% for reporting of absolutely necessary care within the medical records. The authors concluded that medical records are neither sensitive nor specific. Therefore, for information to be reliably abstracted from medical records, particularly about histologic findings, rASRM stage and endometriosis lesion characteristics, adoption of harmonized surgical and pathology reporting is imperative. For endometriosis, surgical documentation tools such as those developed by the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF) Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonization Project (EPHect) are essential (Becker et al., 2014). For cancer discovery, consistent accuracy and detail, including tumor and patient characteristics, has been critical to informative sub-phenotyping and staging (Reis-Filho and Pusztai, 2011; Vaughan et al., 2011). This must occur for women with endometriosis.

The present study is the largest to evaluate the validity of self-reported endometriosis; it includes four large cohort studies with a diverse range of age and population groups including both general population and healthcare providers. Additionally, for GUTS, NHSII and BWHS, we had detailed information on confirmation by laparoscopic surgery, and within GUTS and NHSII, we had information on reporting of AFS or rASRM stage and the presence or absence of endometriomas or deep endometriosis. The medical record abstraction was conducted separately among the four cohort studies, potentially leading to differences in classification of participants. However, we standardized the information abstracted from the medical records as much as possible to minimize this effect. Additionally, we did not have complete information for all the cohorts. We were missing information on histologic confirmation for E3N and BWHS and on reporting of AFS/rASRM stage and endometriosis macro phenotype for BWHS and E3N. However, we do not expect to have seen large differences in the availability of stage and endometriosis macro phenotype information in the BWHS and E3N given that these data were absent from the majority of the records from NHSII and GUTS. The response for the BWHS validation study was low (20%), probably because the BWHS sought records from all women who reported endometriosis instead of restricting to a random sample of women who had recently responded to questionnaires, as was done in the other cohorts.

Conclusion

Overall, we observed that endometriosis is self-reported with reasonable accuracy (84% overall confirmation proportion, ranging from 72 to 95% among these cohorts), and reports of endometriosis confirmed by laparoscopy are exceptionally accurate (≥95%, ranging from 95 to 100% among these cohorts). Abstraction of more details was ineffective, as documentation of endometriosis presentation was often absent from medical records and lacking basic phenotypic details and consistent descriptions even when documented. This reinforces the need for harmonized clinical and surgical data documentation to further endometriosis care and discovery.

Data availability

For the Nurses’ Health Study II and Growing Up Today Study, further information including the procedures to obtain and access data is described at https://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/researchers (contact email: nhsaccess@channing.harvard.edu). For the Black Women’s Health Study, further information including procedures to access data is described at https://www.bu.edu/bwhs/for-researchers/. For the E3N, the data used and analyzed in the current study are available from Dr. Marina Kvaskoff (Marina.kvaskoff@gustaveroussy.fr) upon reasonable and justified request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lori Ward for overseeing medical record collection and review for NHSII and GUTS and Allison Vitonis, Cameron Fraer, McKenzie Goodwin, and Ayo Fadyomi for their help with reviewing the GUTS and NHSII second wave medical records. This is also an important opportunity to acknowledge the altruism of study participants who commit so much effort to these large, longstanding population cohorts simply to benefit women’s health. Their self-reports are valid, and yet are all too often not believed or dismissively defined as ‘low quality’ data. We would also like to acknowledge the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as the home of the Nurses’ Health study.

Authors’ roles

S.A.M. designed the study with critical discussions from L.A.W., J.R.P., and M.K., A.L.S., L.A.W., J.R.P., Z.O.S., L.M.K., P.V., M.K., and S.A.M. contributed to the data collection and execution of the study with A.L.S., Z.O.S., L.M.K., P.V., and M.K. contributing to the statistical analyses. A.L.S., L.A.W., J.R.P., M.K., K.L.T., and S.A.M. contributed to the interpretation of the data. A.L.S. drafted the original manuscript version and all authors contributed to reviewing and editing the final manuscript draft.

Funding

This project was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development grants HD48544, HD52473, HD57210, and HD94842, National Cancer Institute grants CA50385, R01CA058420, UM1CA164974, and U01CA176726, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant U01HL154386. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. AS, SM, and KT were additionally supported by the J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation. MK was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship within the 7th European Community Framework Programme (#PIOF-GA-2011-302078) and is grateful to the Philippe Foundation and the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation for their financial support. Funders had no role in the study design, conduct of the study or data analysis, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of interest

L.A. Wise has served as a fibroid consultant for AbbVie, Inc for the last 3 years and has received in-kind donations (e.g. home pregnancy tests) from Swiss Precision Diagnostics, Sandstone Diagnostics, Kindara.com, and FertilityFriend.com for the PRESTO cohort. SA Missmer serves as an advisory board member for AbbVie and a single working group service for Roche; neither are related to this study. No other authors have a conflict of interest to report. Funders had no role in the study design, conduct of the study or data analysis, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplementary data

References

- Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA, Singh SS, Taylor HS . Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;220:354.e1–354.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine Classification of Endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril 1997;67:817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CM, Laufer MR, Stratton P, Hummelshoj L, Missmer SA, Zondervan KT, Adamson GD, Adamson GD, Allaire C, Anchan R. et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project: I. Surgical phenotype data collection in endometriosis research. Fertil Steril 2014;102:1213–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavel-Chapelon F, Group ES, for the E3N Study Group. Cohort profile: the French E3N cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi M, Kulkarni MT, Missmer SA . Is endometriosis more common and more severe than it was 30 years ago? J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27:452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck J, Peabody JW, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M, Glassman P . How well does chart abstraction measure quality? A prospective comparison of standardized patients with the medical record. Am J Med 2000;108:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ . Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:784–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis-Filho JS, Pusztai L . Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: classification, prognostication, and prediction. Lancet 2011;378:1812–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg L, Adams-Campbell L, Palmer JR . The Black Women’s health study: a follow-up study for causes and preventions of illness. J Am Med Womens Assoc 1995;50:56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell C, Palmer JR, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L . Follow-up of a large cohort of Black women. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:845–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavalainen L, Lassus H, But A, Tiitinen A, Härkki P, Gissler M, Pukkala E, Heikinheimo O . Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Risk of gynecologic cancer according to the type of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:1095–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha R, Marions L, Tornvall P . Validity of self-reported endometriosis and endometriosis-related questions in a Swedish female twin cohort. Fertil Steril 2017;107:174–178.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha R, Pettersson HJ, Svedberg P, Olovsson M, Bergqvist A, Marions L, Tornvall P, Kuja-Halkola R . Heritability of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2015;104:947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota Y, Attia J, Gordon SD, Henders AK, Holliday EG, Rahmioglu N, Macgregor S, Martin NG, McEvoy M, Morris AP. et al. Genetic burden associated with varying degrees of disease severity in endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 2015;21:594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafrir AL, Farland LV, Shah DK, Harris HR, Kvaskoff M, Zondervan K, Missmer SA . Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: a critical epidemiologic review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2018;51:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American Fertility Society. Classification of endometriosis. The American Fertility Society. Fertil Steril 1979;32:633–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American Fertility Society. Revised American Fertility Society classification for endometriosis: 1985. Fertil Steril 1985;43:347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar SA, Macones GA, Mitchell LE, Martin NG . Genetic influences on premature parturition in an Australian twin sample. Twin Res 2000;3:80–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworoger SS, Sluss P, Hankinson SE . Association between plasma prolactin concentrations and risk of breast cancer among predominately premenopausal women. Cancer Res 2006;66:2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan S, Coward JI, Bast RC, Berchuck A, Berek JS, Brenton JD, Coukos G, Crum CC, Drapkin R, Etemadmoghadam D. et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitonis AF, Vincent K, Rahmioglu N, Fassbender A, Buck Louis GM, Hummelshoj L, Giudice LC, Stratton P, Adamson D, Becker CM. et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Endometriosis Phenome and biobanking harmonization project: II. Clinical and covariate phenotype data collection in endometriosis research. Fertil Steril 2014;102:1244–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker LHR, Byrne D, Hummelshoj L, Missmer SA, Saraswat L, Saridogan E, Tomassetti C, Horne AW . Proposal for a new ICD-11 coding classification system for endometriosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2019;241:134–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Koga K, Missmer SA, Taylor RN, Viganò P . Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2018;4:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondervan KT, Becker CM, Missmer SA . Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1244–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For the Nurses’ Health Study II and Growing Up Today Study, further information including the procedures to obtain and access data is described at https://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/researchers (contact email: nhsaccess@channing.harvard.edu). For the Black Women’s Health Study, further information including procedures to access data is described at https://www.bu.edu/bwhs/for-researchers/. For the E3N, the data used and analyzed in the current study are available from Dr. Marina Kvaskoff (Marina.kvaskoff@gustaveroussy.fr) upon reasonable and justified request.