Abstract

A head-to-head comparison of outcomes of unrelated donor allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for AML between reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) and myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens using thymoglobulin for GVHD prophylaxis is limited. We evaluated outcomes of 122 AML patients who received either busulfan (Bu)/fludarabine (Flu)/low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) as RIC (n = 64, 52%) or Bu/Flu as MAC (n = 58, 48%), and thymoglobulin 4.5 mg/kg total dose between day − 3 to − 1 for GVHD prophylaxis. Grades III–IV acute GVHD (aGVHD) was lower with Bu/Flu/TBI compared with Bu/Flu (6.2% vs 26.1%, p = 0.009). At 1 year, Bu/Flu/TBI was associated with similar chronic GVHD (41.2% vs 44.8%, p = 0.75), OS (61.9% vs 56.9%, p = 0.69), relapse rate (29.9% vs 20.7%, p = 0.24), relapse-free survival (52.8% vs 50%, p = 0.80), non-relapse mortality (17.4% vs 29.3%, p = 0.41), and GVHD-free relapse-free survival (24.2% vs 27.5%, p = 0.80) compared with Bu/Flu. Multivariable analysis did not reveal any difference in outcomes between both regimens. In summary, thymoglobulin at 4.5 mg/kg did not have any adverse impact on survival when used with RIC regimen. Both Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu conditioning regimens yielded similar survival.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Thymoglobulin (ATG), Allogeneic stem cell transplantation, Unrelated donor transplant, Reduced intensity conditioning regimen, Myeloablative conditioning regimen

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) is the curative treatment modality for intermediate and adverse risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [1]. Post-transplant relapse and GVHD are two major factors affecting the efficacy of alloSCT. Conditioning regimens play an important role in balancing both factors. Myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens improve outcomes in young AML patients undergoing transplant in complete remission (CR). The BMT CTN 0901 study randomized AML-MDS patients up to 65 years into MAC and reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens. Interim analysis showed a higher rate of relapse and lower overall survival (OS) in AML patients undergoing RIC compared to MAC alloSCT [2]. Unfortunately MAC regimens are not considered in older or frail patients due to poor tolerance leading to higher non-relapse mortality (NRM) and adverse OS [3–5]. RIC, on the other hand, relies more on graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect, is better tolerated, and is widely used in older patients [6–10]. Disease relapse, however, remains one of the major causes of failure of RIC alloSCT. Addition of low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) to RIC regimens has shown to inhibit host immune response, facilitate full donor chimerism [11], and improve alloSCT outcomes [12–14].

With an aging population, the incidence of AML will rise, and use of unrelated donor (URD) alloSCT is expected to increase. Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) when incorporated with MAC and RIC regimens has been shown to reduce acute and chronic GVHD rates [15] and improve GVHD-free relapse-free survival (GRFS) [16–18]. However, in vivo T cell depletion carries the risk of increased disease relapse and opportunistic viral infections [15, 19]. The risk of relapse is particularly higher when ATG is used with RIC regimen, as it attenuates the GVL effect of the allograft. Previous large retrospective studies evaluated the impact of ATG on RIC URD alloSCT outcomes; however, they are limited by heterogeneity of patient population, disease characteristics, stem cell source, and/or ATG dosing [20–22]. An EBMT study evaluating in vivo T cell depletion (alemtuzumab, thymoglobulin) in AML in first complete remission (CR1) after RIC matched-sibling alloSCT demonstrated reduced acute and chronic GVHD and no differences in relapse, NRM, and overall survival [21]. Conversely, a CIBMTR study assessing in vivo T cell depleting agents (alemtuzumab, ATG) in RIC alloSCT showed reduced GVHD but increased relapse and adverse disease-free and overall survival [22]. Both these studies used various formulations of ATG at different doses.

At our institute, we use rabbit ATG (Thymoglobulin, Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA; total dose of 4.5 mg/kg) in combination with tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) for GVHD prophylaxis in URD transplants as previously described [18]. This is the first study comparing outcomes of URD transplants for AML patients between RIC and MAC regimens when thymoglobulin was used for GVHD prophylaxis. The objective of this study was to evaluate impact of pre-transplant thymoglobulin on the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD and long-term outcomes in patients receiving either a RIC (Bu/Flu/TBI) or MAC (Bu/Flu) regimens followed by URD peripheral blood allogeneic stem cell transplant (PBSCT) in AML.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated adult AML patients who underwent URD PBSCT at Karmanos Cancer Institute between January 2005 and December 2017. All received G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood stem cells, and tacrolimus, MMF, and thymoglobulin for GVHD prophylaxis. AML patients were grouped into good risk, intermediate risk, and poor risk categories [23]. Pre-transplant comorbidity index (HCT-CI) was calculated using HCT-CI formula [24]. Acute and chronic GVHD classification and grading was as per physician discretion using standard criteria [25, 26]. This study was approved by the Wayne State University Review Board. This research work is carried out in accordance with the code of ethics of the Declaration of Helsinki for experiments involving humans.

Conditioning regimen and GVHD prophylaxis

The decision to administer conditioning regimens was per treating physician discretion. MAC regimen included IV busulfan 130 mg/m2 daily for 4 days (days − 6 to − 3) and IV fludarabine 30 mg/m2 daily for 5 days (days − 6 to − 2). RIC regimen included IV busulfan 130 mg/m2 daily for 2 days (days − 6 and − 5), IV fludarabine 30 mg/m2 daily for 5 days (days − 6 to − 2), and TBI 200 cGy (day 0). Since 2009, busulfan was dosed pharmacokinetically to achieve AUC of 5000 μmolar × minute.

A total dose of 4.5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin was administered in divided fashion (0.5 mg/kg on day − 3, 1.5 mg/kg on day − 2, and 2.5 mg/kg on day − 1). Tacrolimus was administered intravenously (0.03 mg/kg/day) starting on day − 3 and tapered starting around day + 60 in the absence of active GVHD, with a goal of tapering off completely by day + 180 if patient did not develop GVHD. The initial dose of tacrolimus was 0.03 mg/kg/day, and then, the dose was adjusted with a target trough level of 5 to 15 ng/ml. IV MMF was initiated at 15 mg/kg three times daily from day − 3 and stopped at day + 30.

Statistics

Definition and study endpoints

The endpoints of this study were to compare cumulative incidence and severity of acute and chronic GVHD, OS, relapse rate, NRM, RFS, and GVHD-free relapse-free survival (GRFS) between Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu regimens.

Statistical methods

Baseline patient characteristics were summarized using count and percentage for categorical variables, and median and range for continuous variables. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare groups for continuous variables and Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Length of hospital stay was calculated from admission to discharge following transplant. OS was defined from transplant to death from any cause. Patients who were alive were considered censored at the date of the last observation. RFS was defined from transplant to relapse or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients who were alive without relapse were considered censored at the date of the last observation. GRFS was defined from transplant to grades III–IV acute GVHD (aGVHD), extensive chronic GVHD (cGVHD), disease relapse, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to summarize the distributions of GRFS, RFS and OS. The cumulative incidences of aGVHD and cGVHD were calculated with relapse or death without GVHD as competing risks. When calculating the cumulative incidence of grades II–IV aGVHD, grades III–IV aGVHD and extensive cGVHD, the events of grade I aGVHD, those of grades I–II aGVHD and those of limited cGVHD were ignored, respectively. The cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM were calculated with death without relapse for relapse and death with relapse for NRM, respectively, as competing risks. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were fit to assess associations between covariates and survival benefit (RFS and OS). For aGVHD, cGVHD, relapse, and NRM, the proportional subdistribution hazards regression model in competing risks was used for univariable and multivariable analyses with covariates. The covariates were selected based on a univariable p value of 0.05 among 12 patient baseline characteristics (age at transplant, sex, disease status at transplant, HCT-CI, cytogenetics at diagnosis, ABO matching, CMV serotype, sex mismatch, HLA match, Karnofsky Performance Score, CD34, and total nucleated cells) for all multivariable analyses to assess associations between group and outcomes. Based on univariable analysis, two covariates (age at transplant and comorbidity index) were selected for aGVHD and one covariate (disease status at transplant) for NRM and RFS. No covariate was selected for other outcomes (i.e., cGVHD, relapse, GRFS, and OS). In particular, multivariable analyses for cGVHD included aGVHD as an additional covariate; for relapse, NRM and RFS included aGVHD and extensive cGVHD as additional covariates, and for OS included aGVHD, extensive cGVHD, and relapse as additional covariates. The proportional hazard assumption was checked, and no violation was found except for aGVHD, cGVHD, and relapse, which were resolved using time-varying covariates. The follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier estimate.

Results

Patient characteristics

From January 2005 through December 2017, 122 patients with AML underwent URD PBSCT. Of these, 88 (72%) patients had de novo and 34 (28%) had secondary AML (Table 1). Sixty-four patients (52%) received Bu/Flu/TBI as a RIC regimen, and 58 (48%) received Bu/Flu as a MAC regimen. Patients in Bu/Flu/TBI were older (66 vs 53 years, p < 0.001), had worse Karnofsky performance status (70% vs 80%, p = 0.03), a higher proportion had intermediate risk AML (72% vs 43%, p = 0.001), and a higher proportion received 8/8 HLA matched URD (88% vs 64%, p = 0.004) compared to Bu/Flu.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| BU-FLU-TBI (N = 64) | BU-FLU (N = 58) | All (N = 122) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age at transplant, median (range) | 66 (44,77) | 52.5 (20,70) | 60 (20,77) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, no. (%) | > 0.99 | |||

| Male | 34 (53) | 30 (52) | 64 (52) | |

| Female | 30 (47) | 28 (48) | 58 (48) | |

| Race, no. (%) | 0.169 | |||

| Caucasian | 63 (98) | 53 (91) | 116 (95) | |

| African-American | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| AML, no. (%) | 0.108 | |||

| De novo | 42 (66) | 46 (79) | 88 (72) | |

| Secondary | 22 (34) | 12 (21) | 34 (28) | |

| Disease status at transplant, no. (%) | 0.869 | |||

| First complete remission | 36 (56) | 27 (47) | 63 (52) | |

| Second complete remission | 12 (19) | 12 (21) | 24 (20) | |

| Relapse | 7 (11) | 8 (14) | 15 (12) | |

| Primary induction failure | 6 (9) | 7 (12) | 13 (11) | |

| No treatment | 3 (5) | 4 (7) | 7 (6) | |

| Cytogenetics at diagnosis, no. (%)@ | 0.001 | |||

| Good risk | 0 (0) | 5 (9) | 5 (4) | |

| Intermediate risk | 46 (72) | 25 (43) | 71 (58) | |

| Poor risk | 14 (22) | 22 (38) | 36 (30) | |

| Number of transplant, no. (%) | 0.668 | |||

| 1 | 62 (97) | 55 (95) | 117 (96) | |

| 2 | 2 (3) | 3 (5) | 5 (4) | |

| Comorbidity index, median (range) | 2 (0,10) | 1 (0,7) | 2 (0,10) | 0.106 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status, median (range)$ | 70 (60,100) | 80 (50,90) | 70 (50, 100) | 0.031 |

| ABO matching (donor/recipient), no. (%) | 0.939 | |||

| Match | 33 (52) | 29 (50) | 62 (51) | |

| Major mismatch | 12 (19) | 10 (17) | 22 (18) | |

| Minor mismatch | 18 (28) | 19 (33) | 37 (30) | |

| Bidirectional | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| CMV serotype (donor/recipient), no. (%) | 0.156 | |||

| +/+ | 20 (31) | 9 (16) | 29 (24) | |

| −/+ | 19 (30) | 23 (40) | 42 (34) | |

| +/− | 9 (14) | 6 (10) | 15 (12) | |

| −/− | 16 (25) | 20 (34) | 36 (30) | |

| SEX mismatch (donor/recipient), no. (%) | 0.561 | |||

| M/M | 25 (39) | 24 (41) | 49 (40) | |

| M/F | 22 (34) | 16 (28) | 38 (31) | |

| F/M | 9 (14) | 6 (10) | 15 (12) | |

| F/F | 8 (12) | 12 (21) | 20 (16) | |

| HLA match, no. (%) | 0.004 | |||

| 8/8 | 56 (88) | 37 (64) | 93 (76) | |

| 7/8 | 8 (12) | 19 (33) | 27 (22) | |

| 6/8 | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | |

| CD34, median (range)* | 7.38 (2.58, 212.1) | 7.64 (2.97, 511.4) | 7.6 (2.58, 511.4) | 0.500 |

| Total nucleated cells, median (range)& | 695.8 (2.44, 1615.7) | 748.95 (7.49, 1659.5) | 721.5 (2.44, 1659.5) | 0.164 |

Data are not available for one patient

data are not available for 3 patients

data are not available for 5 patients

data are not available for 10 patients

data are not available for 11 patients

Engraftment and hematological recovery

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 12 (range, 9–21) and 11 (range, 7–19) days for Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, respectively (p = 0.05), while platelet engraftment time was 15 (range, 0–33) days for both groups (p = 0.38). One patient in the Bu/Flu group had primary graft failure. Median length of hospitalization was 25 (range, 19–46) and 27 (range, 20–90) days for Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, respectively (p = 0.05). Donor chimerism was evaluated around day + 30 post-transplant. Median donor cell percentage was 100% for both myeloid and lymphoid lineage in both groups.

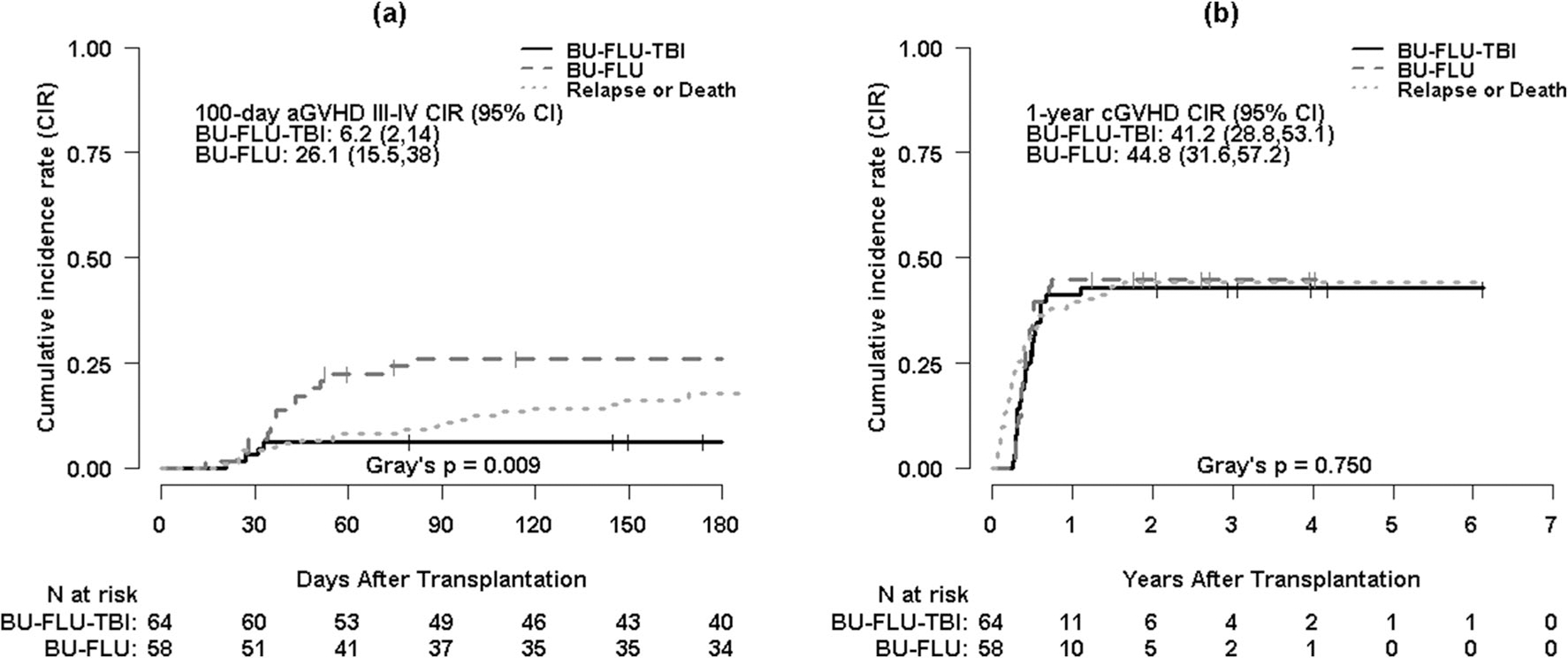

Acute and chronic GVHD

Six-month cumulative incidence of grades II–IV aGVHD was 26.6% (95% CI, 16.4–37.9%) and 55.6% (95% CI, 41.6–67.5%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, respectively (p = 0.002). Cumulative incidence of grades III–IV aGVHD at 6 months is 6.2% (95% CI, 2–14%) and 26.1% (95% CI, 15.5–38%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, respectively (p = 0.009) (Fig. 1a). One-year cumulative incidence of cGVHD is 41.2% (95% CI, 28.8–53.1%) and 44.8% (95% CI, 31.6–57.2%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, respectively (p = 0.75) (Fig. 1b). After adjusting for age at transplant and HCT-CI, multivariable analysis did not demonstrate any significant difference in aGVHD between Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu groups (HR = 1.71, p = 0.10). Similarly, no difference in cGVHD is noted between the two groups (HR = 0.83, p = 0.51) in multivariable analysis (Table 2). Acute GVHD is associated with a high risk of cGVHD (HR = 2.73, p = 0.002) (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

a Cumulative incidence curves for grades III–IV acute GVHD (aGVHD III–IV) with disease relapse or death as competing risks by conditioning regimen. b Cumulative incidence curves for chronic GVHD (cGVHD) with disease relapse or death as competing risks by conditioning regimen

Table 2.

Multivariable analyses of acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, non-relapse mortality (NRM), relapse, relapse-free survival (RFS), GVHD-free/relapse-free survival (GRFS), and overall survival (OS) by group (BU-FLU vs. BU-FLU-TBI)

| HR or SHR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted bya | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Acute GVHD | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 1.708 (0.904, 3.230) | 0.099 | Age at transplant, comorbidity index |

| Chronic GVHD | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 0.828 (0.470, 1.458) | 0.513 | Acute GVHD |

| Relapse | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 0.752 (0.401, 1.412) | 0.376 | Disease status at transplant, acute GVHD, extensive chronic GVHD |

| NRM | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 1.022 (0.507, 2.063) | 0.951 | Acute GVHD, extensive chronic GVHD |

| RFS | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 0.833 (0.524, 1.324) | 0.440 | Disease status at transplant, acute GVHD, extensive chronic GVHD |

| GRFS | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 0.952 (0.643, 1.411) | 0.808 | |

| OS | |||

| BU-FLU-TBI | Reference | ||

| BU-FLU | 0.862 (0.526, 1.414) | 0.557 | Acute GVHD, extensive chronic GVHD, relapse |

Multivariable Cox or subdistribution proportional hazard regression analyses were performed after adjusting by these factors; HR, hazard ratio; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Infectious complications

Rate of CMV reactivation was 34% in both groups (p > 0.99). Two patients (3%) in Bu/Flu/TBI and six patients (10%) in Bu/Flu developed GI CMV disease (p = 0.12). Rate of EBV reactivation was 8% and 7% in Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, respectively (p > 0.99). For Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu, Cl. difficile occurred in 25% and 22% of patients, respectively (p = 0.83); systemic bacterial infections occurred in 22% and 21% of patients, respectively (p > 0.99); Aspergillus was noted in 2% and 7%, respectively (p = 0.19); and mucormycosis was observed in 2% patients in Bu/Flu.

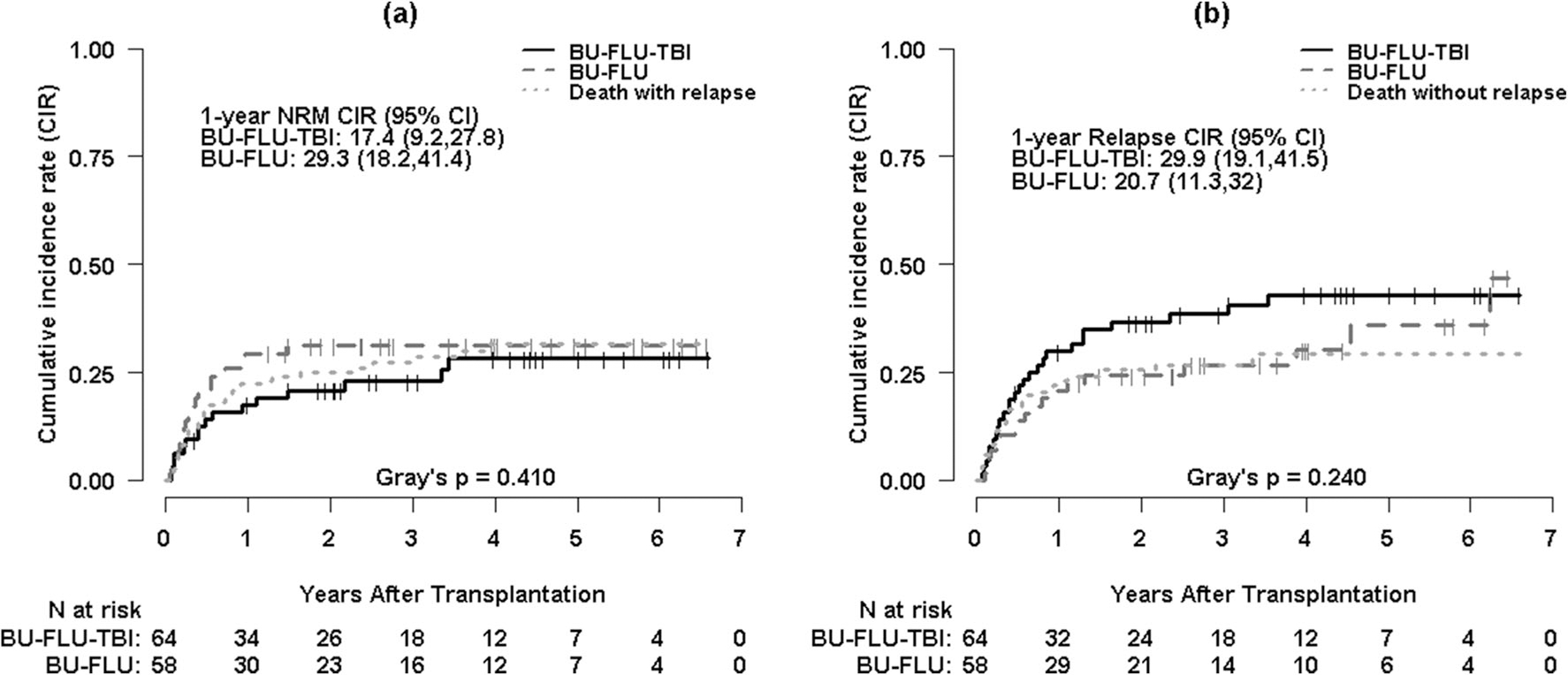

NRM

One-year cumulative incidence of NRM is 17.4% (95% CI, 9.2–27.8%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and 29.3% (95% CI, 18.2–41.4%) for Bu/Flu (p = 0.41) (Fig. 2a). In multivariable analysis, relapse/refractory disease (HR = 2.09, p = 0.04) and aGVHD (HR = 2.66, p = 0.02) are associated with higher risk of NRM (Table S1). There is no significant difference in NRM between Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu groups (HR = 1.02, p = 0.95) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

a Cumulative incidence curves for non-relapse mortality (NRM) with death with relapse as a competing risk by conditioning regimen. b Cumulative incidence curves for relapse with death without relapse as a competing risk by conditioning regimen

Relapse, RFS, and GRFS

One-year cumulative incidence of relapse is 29.9% (95% CI, 19.1–41.5%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and 20.7% (95% CI, 11.3–32%) for Bu/Flu (p = 0.24) (Fig. 2b). Forty-four patients relapsed: 26 (41%) in the Bu/Flu/TBI and 18 (31%) in the Bu/Flu. Fourteen patients relapsed within 100 days, 17 between 100 days and 1 year, and 13 beyond 1 year (p = 0.93). Of relapsed patients, nine (20%) received second alloSCT, two (4%) received donor lymphocyte infusion, seven (16%) had hypomethylating agents, and the rest received supportive care. At the time of the last follow-up, nine patients (20%) with relapse were alive and 35 (80%) died of AML.

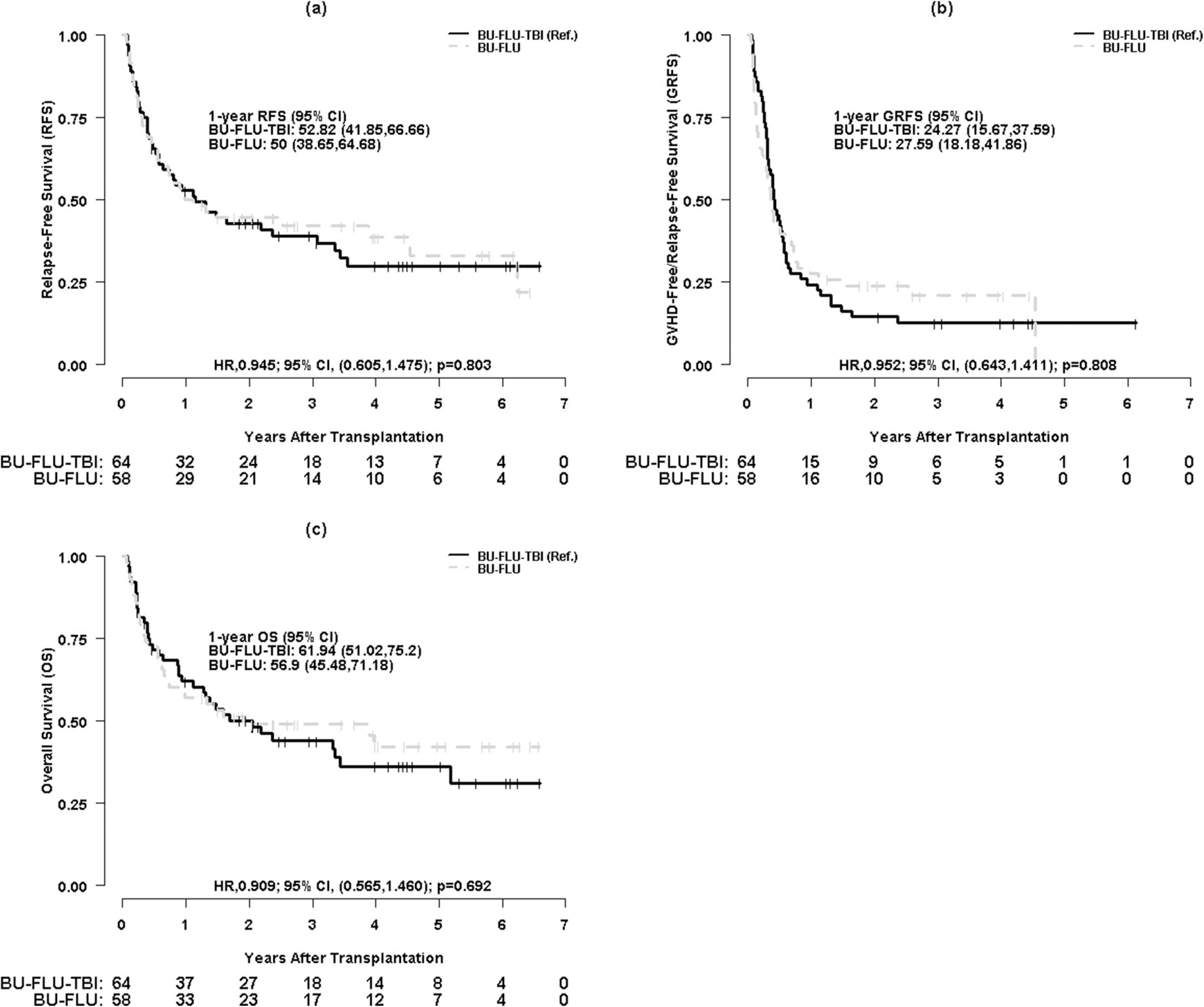

One-year RFS was 52.8% (95% CI, 41.9–66.7%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and 50% (95% CI, 38.7–64.7%) for Bu/Flu (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.61–1.48, p = 0.80). One-year GRFS is 24.3% (95% CI, 15.7–37.6%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and 27.6% (95% CI, 18.2–41.9%) for Bu/Flu (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.64–1.41, p = 0.81) (Fig. 3a, b). No significant difference in relapse rate (HR = 0.75, p = 0.38), RFS (HR = 0.83, p = 0.44), and GRFS (HR = 0.95, p = 0.81) is noted between Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu (Table 2). Extensive cGVHD is associated with superior RFS (HR = 0.51, p = 0.05) (Table S2).

Fig. 3.

a Kaplan-Meier survival curves for relapse-free survival (RFS) by conditioning regimen. b Kaplan-Meier survival curves for GVHD-free relapse-free survival (GRFS) by conditioning regimen. c Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival (OS) by conditioning regimen

Overall mortality

At a median follow-up of 4.4 (95% CI, 2.96 to 5.59) and 4.0 (95% CI, 2.73 to 5.11) years for OS for Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu groups, respectively, 26 patients (41%) in the Bu/Flu/TBI and 27 (47%) in the Bu/Flu were alive and in remission (total n = 53). One-year OS is 61.9% (95% CI, 51.0–75.2%) for Bu/Flu/TBI and 56.9% (95% CI, 45.5–71.2%) for Bu/Flu (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.57–1.46, p = 0.69) (Fig. 3c). In multivariable analysis, survival is not different between both groups (HR = 0.86, p = 0.56) (Table 2). Acute GVHD (HR = 2.67, p = 0.02) and relapse (HR = 9.72, p < 0.001) are associated with adverse OS (Table S2).

The cause of death included disease relapse (54%), acute GVHD (12%), multiorgan failure (12%), infection (10%), chronic GVHD (3%), and second malignancy (1%).

Discussion

ATG has emerged as an important GVHD prophylaxis agent and has crucial effects on immune reconstitution following alloSCT [27–29]. It inhibits T cell proliferation, induces T cell differentiation into regulatory cells, and affects chemotaxis and alters immune cell function [30, 31]. Therefore, the dose and timing of ATG are important to balance GVHD and graft-versus-tumor effects. Previously, we have shown that the addition of thymoglobulin at 4.5 mg/kg total dose to tacrolimus and MMF reduced the incidence of grades III–IV aGVHD, NRM, and improved OS in URD alloSCT recipients [18]. However, there is a paucity of data on how thymoglobulin affects transplant outcomes in patients receiving RIC and MAC regimen. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing a head-to-head comparison of URD PBSCT outcomes between RIC and MAC when ATG was used as a part of GVHD regimen. In this study, we found that patients receiving Bu/Flu/TBI experienced a significantly lower rate of grades III–IV aGVHD compared to those receiving Bu/Flu (6.2% vs 26.1%, p = 0.009). Despite a numerically higher relapse rate (29.9% vs 20.7%, p = 0.24) and lower NRM in those receiving Bu/Flu/TBI (17.4% vs 29.3%, p = 0.41), these differences were not statistically significant. Moreover, OS was not different between the two groups.

The incidence and severity of acute GVHD were significantly higher in Bu/Flu group compared to Bu/Flu/TBI in the univariable analysis, but that difference was not significant after adjusting with other variables in the multivariable analysis. No difference in chronic GVHD was noticed between both groups. Studies have revealed that MAC regimens induce profound tissue injury leading to release of inflammatory markers and higher rates of acute GVHD [32–34]. Compared to a landmark phase III trial evaluating calcineurin inhibitor plus methotrexate or mycophenolate with or without pre-transplant thymoglobulin (4.5 mg/kg total dose) in URD alloSCT, our study noted a lower rate of grades III–IV aGVHD (15.6% vs 28%) and a higher rate of extensive cGVHD (30% vs 13%) [17]. Possible reasons for higher cGVHD in our study include sole use of PBSC allograft (100% vs 89%), higher percentages of mismatched donors (24% vs 16%), and increased concentrations of total nucleated cells in the allograft. Interestingly, the rates of grades III–IV aGVHD and cGVHD in our study were comparable to prior studies utilizing much higher doses of thymoglobulin (7.5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg) [35] and another product of ATG (ATG-Fresenius) [36]. Few studies have demonstrated that the addition of TBI to RIC regimens may minimize graft rejection, improve engraftment [11], and transplant outcomes [12–14]. We found 100% donor chimerism at day + 30, which could be attributed partly to the immunosuppressive effects of TBI to RIC regimen.

Increased risk of relapse remains a concern with the use of rabbit ATG in RIC alloSCT. One-year relapse rate in the entire cohort was 25%. We observed a numerically higher relapse rate with RIC compared to MAC regimen (29.9% vs 20.7%) which was statistically not significant (p = 0.24) [2]. The numerically higher relapse rate seen with RIC regimen was likely related to underlying disease biology than actual effect of thymoglobulin, although the latter cannot be entirely excluded. Two landmark studies have specifically evaluated the use of ATG in RIC alloSCT and observed conflicting results. The CIBMTR study revealed higher relapse rate and lower disease-free and overall survival with T cell antibodies (ATG or alemtuzumab) compared to T cell–replete GVHD regimens after both related and URD transplantation [22]. Three-year relapse rate in the ATG arm was 49% compared to 38.5% in our study. Several differences exist which could explain the differences between our analysis and the CIBMTR study. The CIBMTR study used a combination of horse and rabbit ATG, and two-thirds of patients received a higher dose of thymoglobulin (≥ 6 mg/kg) than our cohort. Conversely, the EBMT study did not demonstrate any difference in relapse, leukemia-free, and overall survival among ATG, alemtuzumab, and control groups in AML CR1 patients undergoing RIC-matched related alloSCT. This study noted that the use of < 6 mg/kg ATG was not associated with increased relapse risk [21]. Consistent with the EBMT study, we did not observe high relapse rate in RIC regimen. This can be explained by the use of low dose of thymoglobulin. By using another product of ATG (ATLG- anti-T-lymphocyte globulin; formerly ATG-Fresenius), Soiffer et al. revealed lower PFS and OS with ATLG in acute leukemia patients undergoing myeloablative URD transplants [15]. The difference in the results can be explained by the use of TBI as a myeloablative regimen and different antigenic profile of ATLG. TBI as a MAC regimen is associated with profound lymphopenia, which might lead to excess level of ATLG and indirectly higher relapse rate.

In vivo T cell depletion carries an increased risk of infections and it is often dose-dependent. In a study by Bacigalupo et al., thymoglobulin at 15 mg/kg was associated with a significantly higher rate of lethal infections and NRM in URD transplants [35]. A prior study had shown comparable rate of aGVHD and significantly lower rates of CMV infections and NRM when thymoglobulin dose was reduced from 7.5 to 6 mg/kg [37]. Several studies have shown favorable outcomes of RIC alloSCT when thymoglobulin was dosed between 5 and 7 mg/kg [20, 38, 39]. Our results corroborate with these studies and indicate that thymoglobulin at 4.5 mg/kg can be given without excessive NRM in URD alloSCT. We noticed that relapse/refractory disease at transplant was associated with increased risk of NRM. We hypothesize that patients with relapse/refractory AML are predisposed to increased risk of cumulative chemotherapy-related toxicities and infectious complications related to prolonged cytopenia, which might lead to increased NRM. No difference in RFS or survival was noted between Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu in the multivariable analysis, which we think could be related to the use of low dose of thymoglobulin. Our results indicate that this dose of thymoglobulin may be enough to prevent GVHD without causing adverse impact on survival.

One of the limitations of this study is that the choice of conditioning regimen was based on physician discretion indicating a potential selection bias. The major strengths of our study is homogeneous population in terms of disease (all AML patients), conditioning regimen (Bu/Flu/TBI and Bu/Flu), GVHD prophylaxis (tacrolimus, MMF and thymoglobulin), source of stem cells (only PBSC), and donor type (unrelated donors). Given the single center experience and universal practice pattern among these patients, our cohort seems to reflect the impact of thymoglobulin on the transplant outcomes accurately in this population.

In summary, we conclude that in vivo T cell depletion with thymoglobulin does not affect survival in recipients of RIC compared to MAC regimens in AML patients undergoing URD PBSCT. Thymoglobulin was associated with a marginally reduced rate of severe acute GVHD when used with a RIC regimen.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Not applicable

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-021-04445-8.

Availability of data and material Available up on request

Code availability Not applicable

References

- 1.Peccatori J, Ciceri F (2010) Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 95(6):857–859. 10.3324/haematol.2010.023184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott BL, Pasquini MC, Logan BR, Wu J, Devine SM, Porter DL, Maziarz RT, Warlick ED, Fernandez HF, Alyea EP, Hamadani M, Bashey A, Giralt S, Geller NL, Leifer E, Le-Rademacher J, Mendizabal AM, Horowitz MM, Deeg HJ, Horwitz ME (2017) Myeloablative versus reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol 35(11):1154–1161. 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.7091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cahn JY, Labopin M, Schattenberg A, Reiffers J, Willemze R, Zittoun R, Bacigalupo A, Prentice G, Gluckman E, Herve P, Gratwohl A, Gorin NC (1997) Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia in patients over the age of 40 years. Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Leukemia 11(3):416–419. 10.1038/sj.leu.2400573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallen H, Gooley TA, Deeg HJ, Pagel JM, Press OW, Appelbaum FR, Storb R, Gopal AK (2005) Ablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults 60 years of age and older. J Clin Oncol 23(15):3439–3446. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zikos P, Van Lint MT, Frassoni F, Lamparelli T, Gualandi F, Occhini D, Mordini N, Berisso G, Bregante S, De Stefano F, Soracco M, Vitale V, Bacigalupo A (1998) Low transplant mortality in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: a randomized study of low-dose cyclosporin versus low-dose cyclosporin and low-dose methotrexate. Blood 91(9): 3503–3508 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alyea EP, Kim HT, Ho V, Cutler C, Gribben J, DeAngelo DJ, Lee SJ, Windawi S, Ritz J, Stone RM, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ (2005) Comparative outcome of nonmyeloablative and myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age. Blood 105(4):1810–1814. 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farag SS, Maharry K, Zhang MJ, Perez WS, George SL, Mrozek K, DiPersio J, Bunjes DW, Marcucci G, Baer MR, Cairo M, Copelan E, Cutler CS, Isola L, Lazarus HM, Litzow MR, Marks DI, Ringden O, Rizzieri DA, Soiffer R, Larson RA, Tallman MS, Bloomfield CD, Weisdorf DJ, Acute Leukemia Committee of the Center for International B, Marrow Transplant R, Cancer, Leukemia Group B (2011) Comparison of reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation with chemotherapy in patients age 60–70 years with acute myelogenous leukemia in first remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17(12):1796–1803. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta V, Daly A, Lipton JH, Hasegawa W, Chun K, Kamel-Reid S, Tsang R, Yi QL, Minden M, Messner H, Kiss T (2005) Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia in patients 60 years or older. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 11(10):764–772. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong R, Giralt SA, Martin T, Couriel DR, Anagnostopoulos A, Hosing C, Andersson BS, Cano P, Shahjahan M, Ippoliti C, Estey EH, McMannis J, Gajewski JL, Champlin RE, de Lima M (2003) Reduced-intensity conditioning for unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as treatment for myeloid malignancies in patients older than 55 years. Blood 102(8):3052–3059. 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modi D, Deol A, Kim S, Ayash L, Alavi A, Ventimiglia M, Bhutani D, Ratanatharathorn V, Uberti JP (2017) Age does not adversely influence outcomes among patients older than 60 years who undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for AML and myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant 52(11): 1530–1536. 10.1038/bmt.2017.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill-Kayser CE, Plastaras JP, Tochner Z, Glatstein E (2011) TBI during BM and SCT: review of the past, discussion of the present and consideration of future directions. Bone Marrow Transplant 46(4):475–484. 10.1038/bmt.2010.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gyurkocza B, Storb R, Storer BE, Chauncey TR, Lange T, Shizuru JA, Langston AA, Pulsipher MA, Bredeson CN, Maziarz RT, Bruno B, Petersen FB, Maris MB, Agura E, Yeager A, Bethge W, Sahebi F, Appelbaum FR, Maloney DG, Sandmaier BM (2010) Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28(17): 2859–2867. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell JA, Irish W, Balogh A, Chaudhry MA, Savoie ML, Turner AR, Larratt L, Storek J, Bahlis NJ, Brown CB, Quinlan D, Geddes M, Zacarias N, Daly A, Duggan P, Stewart DA (2010) The addition of 400 cGY total body irradiation to a regimen incorporating once-daily intravenous busulfan, fludarabine, and antithymocyte globulin reduces relapse without affecting nonrelapse mortality in acute myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16(4):509–514. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen GL, Hahn T, Wilding GE, Groman A, Hutson A, Zhang Y, Khan U, Liu H, Ross M, Bambach B, Higman M, Neppalli V, Sait S, Block AW, Wallace PK, Singh AK, McCarthy PL (2019) Reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine, melphalan, and total body irradiation for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: the effect of increasing melphalan dose on underlying disease and toxicity. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25(4):689–698. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soiffer RJ, Kim HT, McGuirk J, Horwitz ME, Johnston L, Patnaik MM, Rybka W, Artz A, Porter DL, Shea TC, Boyer MW, Maziarz RT, Shaughnessy PJ, Gergis U, Safah H, Reshef R, DiPersio JF, Stiff PJ, Vusirikala M, Szer J, Holter J, Levine JD, Martin PJ, Pidala JA, Lewis ID, Ho VT, Alyea EP, Ritz J, Glavin F, Westervelt P, Jagasia MH, Chen YB (2017) Prospective, randomized, double-blind, phase III clinical trial of anti-T-lymphocyte globulin to assess impact on chronic graft-versus-host disease-free survival in patients undergoing hla-matched unrelated myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 35(36):4003–4011. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.8177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finke J, Schmoor C, Bethge WA, Ottinger H, Stelljes M, Volin L, Heim D, Bertz H, Grishina O, Socie G (2017) Long-term outcomes after standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-human-T-lymphocyte immunoglobulin in haemopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: final results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Haematol 4(6):e293–e301. 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30081-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker I, Panzarella T, Couban S, Couture F, Devins G, Elemary M, Gallagher G, Kerr H, Kuruvilla J, Lee SJ, Moore J, Nevill T, Popradi G, Roy J, Schultz KR, Szwajcer D, Toze C, Foley R, Canadian B, Marrow Transplant G (2016) Pretreatment with antithymocyte globulin versus no anti-thymocyte globulin in patients with haematological malignancies undergoing haemopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol 17(2):164–173. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00462-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ratanatharathorn V, Deol A, Ayash L, Cronin S, Bhutani D, Lum LG, Abidi M, Ventimiglia M, Mellert K, Uberti JP (2015) Low-dose antithymocyte globulin enhanced the efficacy of tacrolimus and mycophenolate for GVHD prophylaxis in recipients of unrelated SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 50(1):106–112. 10.1038/bmt.2014.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Barisione G, Bruzzi P, Guidi S, Alessandrino PE, di Bartolomeo P, Oneto R, Bruno B, Sacchi N, van Lint MT, Bosi A, Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo O (2006) Thymoglobulin prevents chronic graft-versus-host disease, chronic lung dysfunction, and late transplant-related mortality: long-term follow-up of a randomized trial in patients undergoing unrelated donor transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 12(5):560–565. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devillier R, Furst S, El-Cheikh J, Castagna L, Harbi S, Granata A, Crocchiolo R, Oudin C, Mohty B, Bouabdallah R, Chabannon C, Stoppa AM, Charbonnier A, Broussais-Guillaumot F, Calmels B, Lemarie C, Rey J, Vey N, Blaise D (2014) Antithymocyte globulin in reduced-intensity conditioning regimen allows a high disease-free survival exempt of long-term chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 20(3):370–374. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron F, Labopin M, Blaise D, Lopez-Corral L, Vigouroux S, Craddock C, Attal M, Jindra P, Goker H, Socie G, Chevallier P, Browne P, Sandstedt A, Duarte RF, Nagler A, Mohty M (2014) Impact of in vivo T-cell depletion on outcome of AML patients in first CR given peripheral blood stem cells and reduced-intensity conditioning allo-SCT from a HLA-identical sibling donor: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 49 (3):389–396. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, Kan F, Artz A, Champlin RE, Devine S, Isola L, Lazarus HM, Marks DI, Porter DL, Waller EK, Horowitz MM, Eapen M (2011) Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood 117(25):6963–6970. 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armand P, Gibson CJ, Cutler C, Ho VT, Koreth J, Alyea EP, Ritz J, Sorror ML, Lee SJ, Deeg HJ, Storer BE, Appelbaum FR, Antin JH, Soiffer RJ, Kim HT (2012) A disease risk index for patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 120(4):905–913. 10.1182/blood-2012-03-418202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, Baron F, Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Storer B (2005) Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood 106(8):2912–2919. 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, Williams KM, Wolff D, Cowen EW, Palmer J, Weisdorf D, Treister NS, Cheng GS, Kerr H, Stratton P, Duarte RF, McDonald GB, Inamoto Y, Vigorito A, Arai S, Datiles MB, Jacobsohn D, Heller T, Kitko CL, Mitchell SA, Martin PJ, Shulman H, Wu RS, Cutler CS, Vogelsang GB, Lee SJ, Pavletic SZ, Flowers ME (2015) National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21(3):389–401 e381. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, Lerner KG, Thomas ED (1974) Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HLA-matched sibling donors. Transplantation 18(4):295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosch M, Dhadda M, Hoegh-Petersen M, Liu Y, Hagel LM, Podgorny P, Ugarte-Torres A, Khan FM, Luider J, Auer-Grzesiak I, Mansoor A, Russell JA, Daly A, Stewart DA, Maloney D, Boeckh M, Storek J (2012) Immune reconstitution after anti-thymocyte globulin-conditioned hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cytotherapy 14(10):1258–1275. 10.3109/14653249.2012.715243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonnefoy-Berard N, Flacher M, Revillard JP (1992) Antiproliferative effect of antilymphocyte globulins on B cells and B-cell lines. Blood 79(8):2164–2170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zand MS, Vo T, Huggins J, Felgar R, Liesveld J, Pellegrin T, Bozorgzadeh A, Sanz I, Briggs BJ (2005) Polyclonal rabbit antithymocyte globulin triggers B-cell and plasma cell apoptosis by multiple pathways. Transplantation 79(11):1507–1515. 10.1097/01.tp.0000164159.20075.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haidinger M, Geyeregger R, Poglitsch M, Weichhart T, Zeyda M, Vodenik B, Stulnig TM, Bohmig GA, Horl WH, Saemann MD (2007) Antithymocyte globulin impairs T-cell/antigen-presenting cell interaction: disruption of immunological synapse and conjugate formation. Transplantation 84(1):117–121. 10.1097/01.tp.0000266677.45428.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaCorcia G, Swistak M, Lawendowski C, Duan S, Weeden T, Nahill S, Williams JM, Dzuris JL (2009) Polyclonal rabbit antithymocyte globulin exhibits consistent immunosuppressive capabilities beyond cell depletion. Transplantation 87(7):966–974. 10.1097/TP.0b013e31819c84b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couriel DR, Saliba RM, Giralt S, Khouri I, Andersson B, de Lima M, Hosing C, Anderlini P, Donato M, Cleary K, Gajewski J, Neumann J, Ippoliti C, Rondon G, Cohen A, Champlin R (2004) Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease after ablative and nonmyeloablative conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 10(3):178–185. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill GR, Crawford JM, Cooke KR, Brinson YS, Pan L, Ferrara JL (1997) Total body irradiation and acute graft-versus-host disease: the role of gastrointestinal damage and inflammatory cytokines. Blood 90(8):3204–3213 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill GR, Ferrara JL (2000) The primacy of the gastrointestinal tract as a target organ of acute graft-versus-host disease: rationale for the use of cytokine shields in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood 95(9):2754–2759 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, Guidi S, Alessandrino PE, di Bartolomeo P, Oneto R, Bruno B, Barbanti M, Sacchi N, Van Lint MT, Bosi A (2001) Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors: 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Blood 98(10):2942–2947. 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finke J, Bethge WA, Schmoor C, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, Volin L, Ruutu T, Heim DA, Schwerdtfeger R, Kolbe K, Mayer J, Maertens JA, Linkesch W, Holler E, Koza V, Bornhauser M, Einsele H, Kolb HJ, Bertz H, Egger M, Grishina O, Socie G, Group AT-FT (2009) Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 10(9):855–864. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70225-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamadani M, Blum W, Phillips G, Elder P, Andritsos L, Hofmeister C, O'Donnell L, Klisovic R, Penza S, Garzon R, Krugh D, Lin T, Bechtel T, Benson DM, Byrd JC, Marcucci G, Devine SM (2009) Improved nonrelapse mortality and infection rate with lower dose of antithymocyte globulin in patients undergoing reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 15(11): 1422–1430. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devillier R, Crocchiolo R, Castagna L, Furst S, El Cheikh J, Faucher C, Prebet T, Etienne A, Chabannon C, Vey N, Esterni B, Blaise D (2012) The increase from 2.5 to 5 mg/kg of rabbit anti-thymocyte-globulin dose in reduced intensity conditioning reduces acute and chronic GVHD for patients with myeloid malignancies undergoing allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 47(5):639–645. 10.1038/bmt.2012.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malard F, Cahu X, Clavert A, Brissot E, Chevallier P, Guillaume T, Delaunay J, Ayari S, Dubruille V, Mahe B, Gastinne T, Blin N, Harousseau JL, Moreau P, Miplied N, Le Gouill S, Mohty M (2011) Fludarabine, antithymocyte globulin, and very low-dose busulfan for reduced-intensity conditioning before allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with lymphoid malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17(11):1698–1703. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.