INTRODUCTION

Benzodiazepines, including diazepam (DZP), lorazepam (LZP), and midazolam (MDZ), are considered the initial drugs of choice for status epilepticus (SE) treatment. A number of trials have demonstrated their safety and efficacy; however, the failure rate ranges from 10–55%.1,2 This may be attributable, in part, to sub-optimal benzodiazepine dosing and timing of administration.

The Neurocritical Care Society (NCS) and American Epilepsy Society (AES) have published evidence-based guidelines for benzodiazepine use in SE that specify drugs, doses, and routes of administration.1,2 Initial benzodiazepine treatment should consist of either a 10 mg dose of intramuscular (IM) MDZ for patients weighing > 40 kg or 5 mg for those 13–40 kg; or intravenous (IV) LZP 0.1 mg/kg/dose (maximum 4 mg/dose) or IV DZP 0.15–0.2 mg/kg/dose (maximum 10 mg/dose).1,2 The LZP and DZP doses can be repeated if the initial dose fails to stop the seizure. Although not included in the guidelines, based on pharmacokinetics, 10 mg IV MDZ dose can be considered adequate therapy.3

Reports have documented underdosing of benzodiazepines used in SE; however, comprehensive information, regarding patient age, setting, drugs, doses, timing of doses, and routes is limited.4,5 This report describes patterns of benzodiazepine use in SE in a geographically diverse population.

METHODS

The Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial (ESETT) provided an opportunity to systematically observe benzodiazepine administration in patients subsequently determined to have SE unresponsive to benzodiazepines.6 Using pre-enrollment data from ESETT subjects, we describe benzodiazepine treatment with respect to: 1) drug choice, dose, and route of administration, 2) timing and setting in which the drugs were administered, and 3) patient weight (< or ≥ 40 kg for LZP, ≤ or > 40 kg for MDZ, and < or ≥ 66.7 kg for DZP). NCS and AES guidelines were used to define underdosing for our analyses. These weight-based cutoffs were per published guidelines.1,2

Because patients could receive more than one benzodiazepine, the cumulative dose was determined using LZP equivalents to account for differences in drug potencies. Transmucosal benzodiazepines, e.g. DZP or intranasal/buccal MDZ, given prior to emergency medical services (EMS) arrival are included in the calculation of cumulative benzodiazepine dose. For patients weighing ≥ 32 kg, 10 mg MDZ or DZP were considered equal to 4 mg LZP.1,2 For patients weighing < 32 kg, 0.3 mg/kg of DZP IV or 0.2 mg/kg of MDZ IV or 0.3 mg/kg of MDZ IM were considered equal to 0.1 mg/kg LZP IV.1,2 There was no upper limit for the benzodiazepine dose required to qualify for ESETT enrollment. While the ESETT protocol stipulated a minimum cumulative adequate dose for enrollment (Data supplement S1), instructions on the rate and frequency of dosing were not provided. ESETT sites were expected to dose benzodiazepines as per their local standards of care. The settings in which benzodiazepines were administered were categorized as: 1) Prior to EMS, 2) EMS, and 3) Emergency Department (ED).

Data were collected from subjects enrolled at 41 US academic and community hospitals. For this analysis, the ESETT database was frozen on December 12, 2016. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 to compute descriptive statistics.

RESULTS:

This analysis included 207 ESETT subjects: 88 children, 95 adults aged 18–65, and 24 older adults aged ≥ 66 (Data supplement S1). There were 511 administrations with an average (mean ± standard deviation) of 2.47 ± 1.04 doses per subject. LZP comprised of 61% of doses, followed by MDZ (31%), and DZP (8%). Most DZP doses (65%) were given prior to EMS arrival, whereas 68% of MDZ doses were given by EMS personnel, and 94% of LZP doses were administered in the ED. A comparison of routes of administration reveals that 95% of LZP doses were administered IV, while 5% (N=17) were by IM, IN, or buccal routes. With regards to MDZ, 41% of doses were given IM, 45% were by the IV route and the remaining 14% by IN or buccal routes. The rectal route was used for 69% of DZP administrations. Of these, 78% and 96% were in patients younger than 12 and 18 years, respectively.

First Dose of First Benzodiazepine:

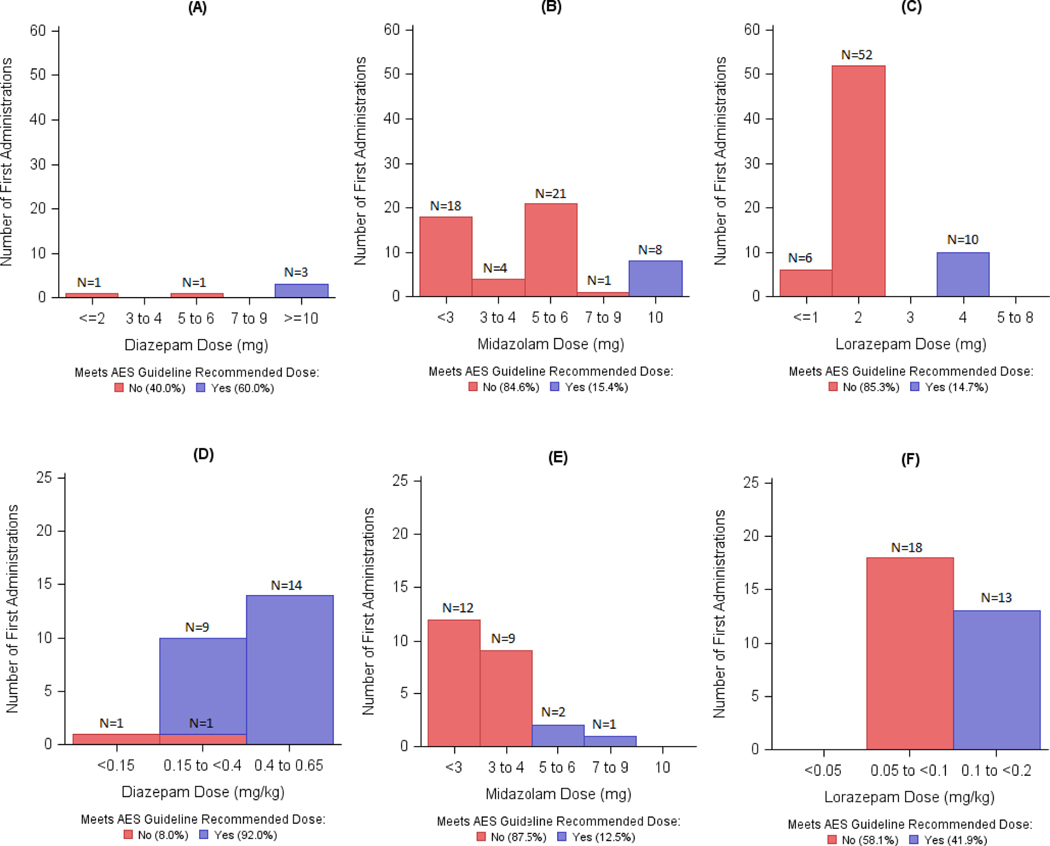

Among all subjects, 102 received their first dose of any benzodiazepine in the ED. Overall, 29.8% of first doses met minimum recommendations per guidelines. Of these, 86.7% of DZP, 14.5% of MDZ and 23.2% of LZP administrations met the minimum dose recommendations. Figure 1 shows that for subjects < 40 kg the guideline recommended LZP (≥ 0.1 mg/kg) or MDZ (≥ 5 mg) dose was administered as a first dose in 41.9% and 12.5% of the cases, respectively. In contrast, for those weighing ≥ 40 kg the recommended LZP (≥ 4 mg) or MDZ recommended (≥ 10 mg) dose was administered in 14.7% and 15.4% of the subjects, respectively. A DZP dose ≥ 10 mg was administered in 60% of the subjects ≥ 66.7 kg, while 96% of DZP administrations were ≥ 0.15 mg/kg in those < 66.7 kg.

Figure 1:

Distribution of first dose of the first administered benzodiazepine (DZP, MDZ or LZP) as actual doses. Top panel: fixed dosing, bottom panel: weight-based dosing. A:DZP doses for those ≥ 66.7kg (IV) or ≥ 50 kg (rectal); B: MDZ doses for those > 40 kg; C: LZP doses for those ≥ 40 kg; D: DZP doses for those < 66.7 kg (IV) or < 50 kg (rectal); E: MDZ doses for those ≤ 40 kg; F: LZP doses for those < 40 kg . Categorized as met (blue) or did not meet (red) guidelines.

Dose per Administration:

Seventy-seven percent of DZP, 10.7% of MDZ and 21.8% of LZP doses administered were at or above the recommendations (Data supplement S1). Prior to EMS, most administrations were DZP (25/37) given at or above the minimum recommended doses, whereas in both the EMS and ED settings, most of the administered benzodiazepine doses were below recommendations.

Cumulative Benzodiazepine Doses:

Cumulative dosing patterns were examined using LZP equivalents (Data supplement S1). Among 138 adults and older children weighing ≥ 32 kg, the cumulative dose in LZP equivalents was < 4 mg in 9%, 4 mg in 42%, 5–6 mg in 25% and > 7 mg in 24%. In 68 children weighing < 32 kg, the cumulative dose was < 0.1 mg/kg in 18%, 0.1 to < 0.2 mg/kg in 44%, 0.2 to < 0.3 mg/kg in 28% and > 0.3 mg/kg in 10% of subjects.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest that many patients with SE who fail benzodiazepine treatment are not receiving recommended initial doses of benzodiazepines. The observed practice was not consistent with published evidence-based guidelines which stipulate that the initial treatment of SE begin with a benzodiazepine administered as early as possible, as a single full dose, and by an appropriate route.1,2 In contrast, we found a pattern of administering multiple, small doses with approximately 70% of patients receiving a lower than guideline recommended first dose of the first drug. If, however, rectal DZP is excluded, the first doses of MDZ and LZP, mostly administered by EMS and/or ED personnel, were below guideline recommendations 80% of the time. Administration of subsequent doses continued the pattern of underdosing. Regardless of the number of administrations, approximately 12% o of patients never received the required cumulative dose needed to meet ESETT eligibility criteria. This potentially reduced response to benzodiazepines as delay in administering appropriate therapy is thought to place patients at risk for longer seizures and poor outcomes.7

Our results extend the findings from earlier reports on initial management of SE.4,5 In a multicenter study of adults, the investigators found that > 80% of patients with SE received a lower than recommended LZP dose.4 Langer and Fountain, in a retrospective study of generalized convulsive SE in 170 children and adults found that only 11% of the patients, all children, received an adequate initial benzodiazepine dose.5 The problem of benzodiazepine underdosing in SE may be attributable to the perceived risk of cardio-respiratory compromise associated with benzodiazepines.8 However, Alldredge et. al showed that the rate of respiratory or circulatory complications was nearly doubled (p=0.08) in untreated SE patients versus those treated with benzodiazepines.8 We also noted that on 17 occasions LZP was administered by IM, IN, or buccal routes. These routes do not support rapid LZP absorption and are inappropriate for SE therapy.9

LIMITATIONS

Our analysis is limited to SE patients who continued to have seizures despite benzodiazepine treatment. Since initial benzodiazepine underdosing is likely associated with treatment failure, our population may overestimate the rate of underdosing among patients treated for SE. While this limits the generalizability of our findings, benzodiazepine underdosing is particularly important in this subpopulation in whom seizures continue and may progress to refractory SE with attendant high rates of morbidity and mortality. Conversely, this analysis may underestimate the rate of underdosing because only those given an adequate cumulative benzodiazepine dose were eligible for ESETT enrollment. It is possible that eagerness to enroll subjects could bias toward lower cumulative benzodiazepine doses. However, in this scenario, EDs would be more likely to administer larger individual doses in order to meet the minimum adequate dose sooner and should not affect EMS practice. Lastly our sample size precluded the analysis of specific factors such as regional effects on dosing patterns.

CONCLUSIONS

Benzodiazepine underdosing for the treatment of SE was common in this geographically diverse set of EDs. This phenomenon may contribute to decreased efficacy. Further, the low doses used per administration in both ED and EMS settings suggests this represents practice culture rather than an artifact in practice driven by study enrollment. Hence, greater educational efforts and overcoming systematic and structural barriers are needed to change clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the ESETT Data and Safety Monitoring Board. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, or the United States Government.

Prior Presentations: This work has been presented as an abstract at the London Innsbruck Colloquium on Status Epilepticus and Acute Seizures, Salzburg, Austria, 6-8 April 2017.

Funding Sources: Research reported in this publication was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke under Awards U01NS088034, U01NS088023, U01NS056975, U01NS059041, and R01NS099653. (Clinical trials.gov identifier NCT01960075)

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure: All authors were supported by the ESETT study grant from NIH/NINDS (U01NS088034). Dr. Coles reports grants from NIH/NINDS, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Neurelis Pharmaceuticals, grants from Sollievo, outside the submitted work; Dr. Shinnar reports grants from NINDS, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from UCB Pharma, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Insys, outside the submitted work; Prof. Cock reports grants from NINDS, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Sage Pharmaceuticals Ltd, personal fees from Eisai Europe Ltd, personal fees from UCB Pharma Ltd, personal fees from UK Epilepsy Nurse Specialist Association, non-financial support from Special Products Ltd, non-financial support from International League Against Epilepsy, Epilepsy Certification (education) Task Force, non-financial support from European Academy of Neurology, personal fees from Bial and Eisai, outside the submitted work; Dr. Fountain reports grants from NINDS, during the conduct of the study; grants from SK Lifesciences, grants from Neurelis, grants from Takeda, grants from GW Pharma, grants from Biogen, grants from UCB, outside the submitted work. Dr. Cloyd reports a grant from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Neurelis Pharmaceuticals, grants from Sollievo, outside the submitted work. In addition, Dr. Cloyd has a patent entitled “Intranasal Drug Delivery” which the University of Minnesota has licensed to Sollievo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brophy GM, Bell R, Claassen J, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit Care 2012;17(1):3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, et al. American Epilepsy Society Guideline Evidence-Based Guideline : Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults : Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr 2016;16(1):48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell DM, Richards G, Dhillon S, et al. A comparative pharmacokinetic study of intravenous and intramuscular midazolam in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 1991;10:183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvarez V, Lee JW, Drislane FW, et al. Practice variability and efficacy of clonazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam in status epilepticus: A multicenter comparison. Epilepsia 2015;56(8):1275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer JE, Fountain NB. A retrospective observational study of current treatment for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav [Internet] 2014;37(2014):95–9. Available from: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleck T, Cock H, Chamberlain J, et al. The established status epilepticus trial 2013. Epilepsia 2013;54(SUPPL. 6):89–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaínza-Lein M, Fernández IS, Ulate-Campos A, Loddenkemper T, Ostendorf AP. Timing in the treatment of status epilepticus: From basics to the clinic. Seizure [Internet] 2018;(May. Available from: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.05.021):0–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, et al. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 2001;345(9):631–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maglalang PD, Rautiola D, Siegel RA, et al. Rescue therapies for seizure emergencies: New modes of administration. Epilepsia [Internet] 2018;(00):1–9. Available from: 10.1111/epi.14479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.