Abstract

Background:

Nonpharmacological and accessible therapies that engage individuals in self-management are needed to address depressive symptoms in pregnancy. The 12-week “Mindful Moms” intervention was designed to empower pregnant women with depressive symptomatology to create personal goals and engage in mindful physical activity using prenatal yoga.

Objectives:

This longitudinal pilot study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of the “Mindful Moms” intervention in pregnant women with depressive symptoms.

Methods:

We evaluated enrollment and retention data (feasibility) and conducted semistructured interviews (acceptability). We evaluated the intervention’s effects over time on participants’ depressive symptoms, anxiety, perceived stress, self-efficacy, and maternal–child attachment, and we compared findings to an archival comparison group, also assessed longitudinally.

Results:

Enrollment and retention rates and positive feedback from participants support the intervention’s acceptability and feasibility. “Mindful Moms” participants experienced decreases in depressive symptoms, perceived stress, anxiety, ruminations, and maternal–child attachment and no change in physical activity self-efficacy from baseline to postintervention. Comparisons of the “Mindful Moms” intervention to the comparison groups over time indicated differences in depressive symptoms between all groups and a trend in differences in perceived stress.

Discussion:

Results support the feasibility and acceptability of “Mindful Moms” for pregnant women with depressive symptoms and suggest that further research is warranted to evaluate this intervention for reducing depressive and related symptoms. Lack of a concurrent control group, with equivalent attention from study staff, and no randomization limit the generalizability of this study; yet, these preliminary findings support future large-scale randomized controlled trials to further evaluate this promising intervention.

Keywords: depression, mindful, physical activity, pregnancy, yoga

Close to one in four pregnant and postpartum women experience depressive symptoms, and suicide is a leading cause of perinatal mortality (Kendig et al., 2017). Depressive symptoms classically include feelings of sadness, anhedonia or lack of interest in typically pleasurable experiences, and fatigue (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; O’Connor et al., 2019). Despite recent recognition of the importance of perinatal depression screening, many women experiencing symptoms do not receive the standard of care (e.g., psychotherapy and/or antidepressant medications) for reasons such as perceived stigma, concerns about adverse medication effects for the fetus, and costs related to treatment (Clement et al., 2015; Epstein et al., 2014; Siu, 2016). Even when a woman receives standard-of-care therapies, she might not achieve partial or full remission; thus, there is a need to evaluate more accessible and acceptable therapies to address perinatal depressive symptoms.

A self-management intervention, combined with clinician-led motivating features, might be relevant adjuvant care for pregnant women with depressive symptoms. Self-management is typically defined as one’s active engagement in self-monitoring, self-reflection, and taking steps to manage one’s health (Lorig & Holman, 2003; Ryan & Sawin, 2009). Self-management interventions empower patients to participate actively in healthy self-care activities, particularly when combined with methods to motivate individuals and address potential barriers to self-care (Bean et al., 2015). In this study, we evaluated “Mindful Moms,” a self-management intervention that combines a brief, initial motivational interviewing-informed session and 12 weeks of group-based mindful physical activity, via prenatal yoga. Prenatal yoga is a light-intensity physical activity combining gentle physical movements, breathing, and relaxation practices tailored to fit the unique needs of pregnant women (Kinser et al., 2019; Kinser & Williams, 2008; National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2019). Gentle prenatal yoga may be a reasonable adjunctive self-management intervention for pregnant women with depressive symptoms for several reasons. First, pregnant women have expressed interest in nonpharmacological options for symptom management (Evans et al., 2020; Kinser & Masho, 2015a, 2015b). Second, the practice of yoga during pregnancy is safe and appears to improve mental health outcomes (Cramer et al., 2017; Ng et al., 2019). Third, yoga interventions in depressed nonpregnant women reduces ruminations and depressive symptoms (Kinser, Bourguignon, Taylor et al., 2013; Kinser, Bourguignon, Whaley et al., 2013). Fourth, even in a gentle form such as yoga, physical activity appears to have important antidepressant and anxiolytic effects (Cramer et al., 2017; Rimer et al., 2012; Zou et al., 2018), and yoga may contribute to positive experiences with physical activity, in turn increasing motivation for future more vigorous activity. Finally, yoga combines mindfulness with physical activity, which may help individuals mitigate stress responses via “bottom-up” physiological (e.g., parasym-pathetic activation, reduced inflammation) and “top-down” emotional/behavioral (e.g., psychological reappraisal) mechanisms (Kinser et al., 2012).

In line with recent recommendations to evaluate interventions that may prevent and treat perinatal depression (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force et al., 2019), the “Mindful Moms” intervention was developed using a patient-centered, self-management framework and feedback from pregnant women with depressive symptoms to motivate and empower women in healthy gentle physical activity (Kinser et al., 2020). The purpose of this study was to determine feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of the “Mindful Moms” intervention for pregnant women with depression on maternal psychobehavioral outcomes throughout pregnancy and into the early postpartum period—in preparation for future large-scale clinical trials.

METHODS

Research Design, Setting, and Participants

The study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board. The full study protocol and its conceptual framework were previously outlined (Kinser et al., 2020). Briefly, pregnant women were eligible to participate if they were 18 years old or older; 12–28 weeks of gestation at the baseline study visit; spoke English; self-identified as Black or White; had moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms based upon a score of at least 10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); denied active suicidal ideation, psychosis, or mania; and reported a previous history of depressive symptoms. Exclusion criteria were healthcare provider recommendation to avoid physical activity and a regular yoga or meditation practice (more than once per month during the current pregnancy; Kinser et al., 2020). The sample size was determined based upon van Belle’s guidelines for at least 12 observations required to calculate confidence intervals (Kinser et al., 2020). De-identified data from a previous observational study (Lapato et al., 2018) contributed to the creation of an archival comparison group of pregnant women who did not receive any intervention other than usual care; inclusion criteria for that study were Black and White pregnant women who were English-speaking adults, both with and without depressive symptoms. Any participants receiving usual care for depression (defined as use of psychotherapy and/or pharmacological treatments) were welcomed to continue participation in the study, for ethical reasons.

Procedures and Measures

Interested individuals responded to institutional review board-approved recruitment materials made available in the affiliated academic health system, in community-based clinics, in community bulletin boards and events, and through social media. Participants engaged in a standardized private informed consent process and provided written consent. Participants in the “Mindful Moms” group were contacted weekly by a study staff member to enhance retention, collect weekly physical activity minutes, and monitor for any adverse events. As compensation for their time, participants received a $25 gift card at the completion of each of the four assessments. Participants in the “Mindful Moms” group completed self-reported psychobehavioral measures at baseline, midpoint of intervention (Week 6), end of intervention (Intervention Week 12), and at the 6-week postpartum follow-up visit. Feasibility and acceptability measures were obtained through recruitment and retention data, class rosters/attendance at study visits, home physical activity logs, and semistructured interviews. Semistructured interviews were conducted with participants during the postpartum visit and assessing participants’ experiences with the intervention.

Outcome measures included the following: (a) Depressive symptom severity was measured with the PHQ-9 (Sidebottom et al., 2012); scores range from 0 to 27, and higher scores indicate higher depressive symptom severity. (b) Perinatal-specific depressive symptoms were measured by the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., 1987); scores range from 0 to 30, and a score of ≥10 is considered indicative of possible depressive symptoms. (c) Perceived stress was measured with the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, 1994; Hewitt et al., 1992); scores range from 0 to 40, and higher scores represent higher perceived stress. (d) Anxiety was measured with the State Anxiety Form Y (State–Trait Anxiety Inventory; Spielberger, 1983; Tilton, 2008); scores range from 20 to 80, and higher scores indicate higher state anxiety. (e) The Ruminative Responses Scale was used to measure ruminations (Treynor et al., 2003); total scores range from 10 to 40, where higher scores indicate higher rumination. (f) Self-efficacy to engage in physical activity was measured with the Physical Activity Self-Efficacy Scale–Modified (Dishman et al., 2010; Motl et al., 2000); scores range from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy. (g) Maternal–fetal/child attachment was measured using the Maternal–Fetal Attachment Scale (MFAS; Cranley, 1981; McFarland et al., 2011), with wording adapted slightly for the postpartum use; scores range from 24 to 120, with higher scores indicating higher attachment.

Intervention

“Mindful Moms” is a 12-week, manualized intervention combining three key aspects, summarized in Table 1. First, participants were encouraged to engage in mindfulness of symptoms and goal setting through a nurse–participant partnership, initiated at the first baseline visit and continued through weekly check-ins. The research nurse used aspects of motivational interviewing to facilitate the participant’s engagement in self-management (Keeley et al., 2016). The baseline visit involved discussions about whether and how the participant was aware of her depressive symptoms and how she might set goals in actively addressing those symptoms (Bilsker et al., 2012; Lorig & Holman, 2003). For example, some participants’ goals were to attend the weekly prenatal group classes; others had the goal of attending class plus walking for at least 10 minutes per day on other days. Weekly check-ins (via phone, e-mail, text, or in person prior to class) provided opportunities for participants to report home physical activity and strategize ways to overcome barriers in attending class or engaging in home-based activity. Second, participants engaged in mindful physical activity through weekly gentle prenatal yoga group classes. These 75-min classes were manualized and taught by instructors familiar with pregnant and yoga-naïve individuals. Participants joined the classes via rolling admission, and the classes were designed to have repetition of key concepts, breathing practices, and poses each week to enhance participants’ sense of mastery and competence. Each session started with an opportunity for participants to share their experiences. Table 1 provides a sample of one of the manualized classes. Prior to the start of class, participants completed a brief self-assessment to ensure they had no contraindications to physical activity, according to American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines for prenatal exercise (ACOG, 2015). Third, participants applied self-management skills through monitoring depressive symptoms and engaging in home-based physical activity. Participants were provided a study-specific handbook that contained yoga poses practiced during the group sessions as well as suggestions for other pregnancy-safe physical activities (e.g., walking, swimming, dancing) and space to journal about symptom experiences. Intervention fidelity was assessed through monthly staff discussions about possible deviations from the study protocol manual for the yoga classes and nurse discussions with participants.

TABLE 1.

Specific Activities in “Mindful Moms” Intervention

| Key aspect | Specific activities |

|---|---|

| (A) Mindfulness of symptom self-management and motivation for physical activity | At the baseline visit, the nurse and participant:

|

| (B) Mindful physical activity | Weekly group prenatal yoga class:

|

| (C) Applied self-management skills |

|

| Excerpt from weekly group prenatal yoga class manual: | |

| Checking-in and brief discussion with group | Week 3 Theme: Meeting the Mood: Brief discussion—What does “meeting the mood” mean to you? |

| Creation of safe space; empowerment to adapt practice; intention/centering | SAFE SPACE: Reinforce concepts of yoga: an opportunity to connect breathing practices, physical movements, and relaxation to enhance well-being EMPOWERMENT: Reinforce concepts of self-awareness and adapting practice to one’s specific needs, involves an awareness of “now,” letting go of expectation or self-judgment, communication, and permission to modify as needed INTENTION/CENTERING: Our focus this week—Learn to adapt your practice and meet yourself where your mood currently rests, both at home and in class; everyone has a unique experience—you play a role in adapting your yoga practice according to your personal needs and mood; this is an opportunity to become self-aware and self-accepting and develop the practice that is best for you. |

| Pranayama (breathing practices) and Asana (physical poses) |

|

| Guided Savasana (meditation and relaxation) | ❖ Awareness of sensation (guided body scan) ❖ Awareness of breath (guided breathing practice) ❖ Awareness of inner resources (guided meditation) |

ACOG = American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using both SAS v9.4 and JMP Pro 14 statistical software. Descriptive statistics were used for demographics and characteristics of the groups and to evaluate recruitment, retention, and intervention adherence data. For analyses of the “Mindful Moms” group only, a single-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance model was used, with the single factor being “visit.” If the visit effect was found to be significant, post hoc tests were performed comparing the baseline visit least squares mean to all subsequent visits least squares means. All post hoc tests were performed utilizing a Bonferroni correction to control overall Type I error. For the between-group analyses, we calculated means, variances, and covariances/correlations and 95% confidence intervals for the three groups: intervention group, positive comparison group (those with depressive symptoms receiving the usual care), and negative comparison group (those without depressive symptoms) across the study time points. The study from which the archival data were derived used the Symptom Checklist (SCL) Depression Scale; hence, the SCL Depression score was used to determine the type of comparison group (i.e., negative comparison group with a score of <10 on SCL; positive comparison group with a score of ≥10 on SCL; Kinser et al., 2018; Lapato et al., 2018). A repeated-measures analysis of variance was fit using a mixed linear model that included one between-subject factor (group), one within-subject factor (visit), and the Group × Visit interaction. Post hoc tests were performed for each group separately using the least squares mean estimates from the models to assess the significance (if any) in the change in Visit 1 (baseline) to Visit 3 (end of intervention).

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to understand participants’ perceptions of the intervention as a measure of acceptability (Sandelowski, 2000). This process involved the following steps: analysts read the postpartum interview transcripts line by line and assigned codes to key concepts, came to consensus on coding categories to create a codebook, and developed key themes. The team identified quotes to illuminate key themes. To maintain rigor and trustworthiness of the qualitative analysis, we employed two common techniques: All decisions were documented to maintain an audit trail to enhance validity, and we used peer debriefing in which the qualitative analysts discussed their analysis processes and the key findings with research team members to ensure dependability and reliability of analysis (Rodgers & Cowles, 1993).

RESULTS

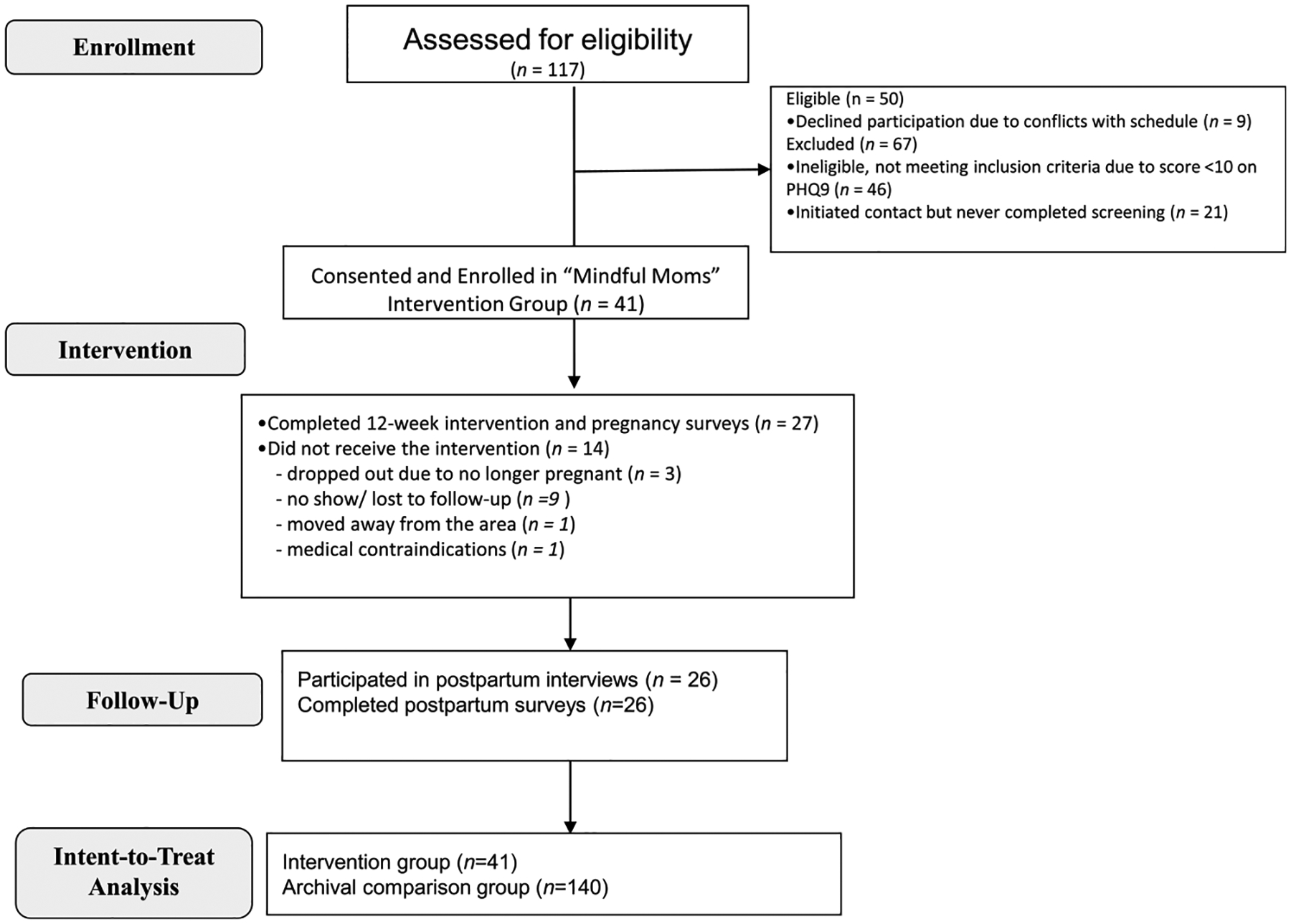

Of the 117 women assessed for eligibility, 46 were excluded primarily based on low score (<10 on the PHQ-9), and 21 women initiated contact with our study staff but never completed screening, as depicted in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram Figure 1. Sample characteristics are reported in Table 2, along with characteristics from the archival comparison group.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow diagram (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials).

TABLE 2.

Demographics and Characteristics of Study Population

| Comparison group (n = 140) | Mindful Moms (n = 41) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.82 (4.88) | 29.10 (5.32) | .7554 |

| Gestational age at baseline, mean weeks (SD) | 13.55 (4.65) | 17.46 (5.64) | <.0001 |

| Race | .0011 | ||

| White | 51% (72/140) | 29% (12/41) | |

| African American/Black | 49% (68/140) | 63% (26/41) | |

| Do not know/refuse to answer | 0% (0/140) | 7% (3/41) | |

| Relationship status | <.0001 | ||

| Married or cohabitating | 39% (54/140) | 76% (31/41) | |

| Single | 59% (83/140) | 24% (10/41) | |

| Do not know/refuse to answer | 2% (3/140) | 0% (0/41) | |

| Employment status | .9753 | ||

| Full-time | 44% (62/140) | 46% (19/41) | |

| Part-time or student | 22% (31/140) | 20% (8/41) | |

| Unemployed | 31% (44/140) | 34% (14/41) | |

| Do not know/refuse to answer | 2% (3/140) | 0% (0/41) | |

| Household income | .0031 | ||

| ≤ $100,000 | 79% (110/140) | 66% (27/41) | |

| > $100,000 | 9% (12/140) | 29% (12/41) | |

| Do not know/refuse to answer | 13% (18/140) | 5% (2/41) | |

| Education | .5501 | ||

| High school or less | 29% (40/140) | 17% (7/41) | |

| Some college | 23% (32/140) | 29% (12/41) | |

| College degree | 25% (35/140) | 29% (12/41) | |

| Some graduate school or graduate degree | 21% (30/140) | 24% (10/41) | |

| Do not know/refuse to answer | 2% (3/140) | 0% (0/41) |

Feasibility

To evaluate feasibility of enrollment and retention, an a priori determined enrollment rate threshold of >80% and retention rate threshold of >60% were set. In all cases of declining to participate in the study (n = 9), this was due to schedule conflicts, representing an 82% enrollment rate. Twenty-seven participants completed the 12-week intervention and all study surveys, representing a retention rate of 66%. For the five individuals who requested to withdraw from the study, the reasons were as follows: no longer pregnant (n = 3), had to move out of the area (n = 1), or developed medical contraindications to physical activity (n = 1). Nine participants were lost to follow-up after the baseline study visit and never received the intervention; the baseline characteristics of these individuals were not different than those who completed the intervention. Of the 27 study completers, the majority (n = 16) attended at least 9 out of the 12 intervention sessions; 96% (n = 26) attended at least 50% of the sessions. Participants reported an average of 141 minutes per week (minimum 0–maximum 1,070) of time in home-based physical activity. Based on the preestablished feasibility criteria for enrollment and retention, the “Mindful Moms” intervention was feasible.

Acceptability

Twenty-six women agreed to participate in postpartum interviews to provide perspectives about the acceptability of the intervention. First, 100% of participants reported enjoying the intervention and finding it beneficial. Participants expressed that they enjoyed the combination of physical and mindful aspects of yoga. This is exemplified in one participant’s summary of her experience: “It helped my physical and emotional well-being.…It helped me slow down.” Second, participants frequently mentioned enjoying the group-based aspect of the intervention because it provided a sense of connectedness with others. For example, a quote from one participant summarizes this sentiment: “It was nice to see other pregnant women going through the same (depression and anxiety) that I was going through.” Participants expressed gratitude that only study participants formed the group prenatal yoga classes, because “it’s easier when you know that everyone’s not pretending that everything is perfect…so this was an ultra-safe space.” Third, participants consistently reported that they appreciated regular check-ins from the study staff, as exemplified in one participant’s statement that the weekly check-ins “helped motivate me and made me accountable.” Several participants were concerned about whether they would continue to engage in mindful physical activity after the end of the study, when the formal reminders were no longer in place. Participants also reported a desire to maintain a connection with fellow participants after the end of the intervention. For example, a participant stated, “It was hard leaving that safe space, where I looked forward every week to seeing how everyone was doing.” A few participants suggested that future studies might create a social media group or a buddy system, in which participants could engage with each other beyond the confines of the study and motivate each other to engage in mindful physical activity. Finally, all participants acknowledged the challenge of regular attendance to an in-person group session on a weekly basis, given conflicting family and work schedules. However, none of the participants expressed interest in a purely online option. For instance, one participant responded, “No way. The best part about it all was the community-building. It’s really powerful to have women together like that.” Rather, participants suggested a “hybrid” format whereby they could engage in an online session as a back-up plan for days when they could not attend the in-person session. Participants also mentioned that providing childcare and offering neighborhood variety of time, day, and location for classes would have made attendance easier.

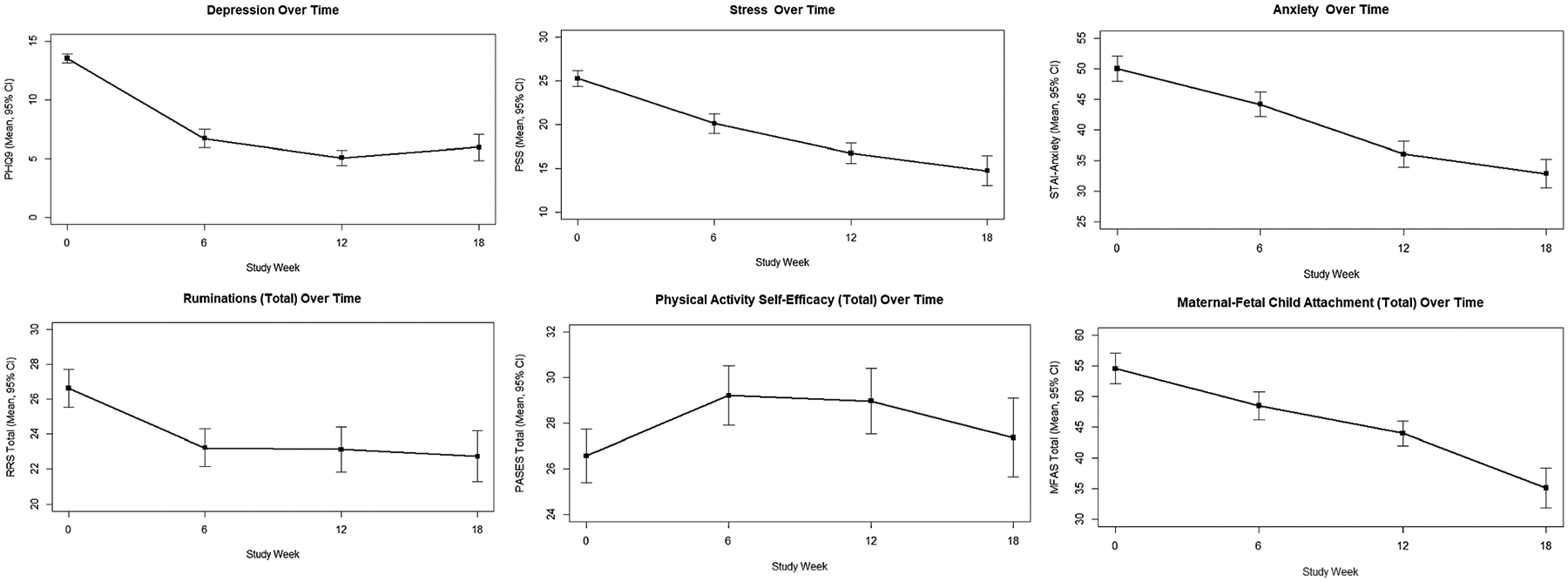

Preliminary Intervention Effects (Baseline to Postpartum)

Changes in symptom scores over time are represented in Table 3 and Figure 2. Overall, there was a significant effect of time on depression symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9, F(3, 26) = 62.87, p < .0001, , and on perinatal-specific depressive symptoms using the EPDS, F(3, 29 = 18.62, p < .0001, , among participants who engaged in the “Mindful Moms” intervention. Similarly, the following scores decreased over time: perceived stress, F(3, 25) = 28.76, p < .0001; anxiety, F(3, 28) = 9.54, ‘p = .0002; total ruminations (Ruminative Responses Scale total), F(3, 25) = 3.90, p = .0202; and maternal–fetal/child attachment (MFAS total), F(3, 28) = 11.37, p < .0001.

TABLE 3.

Change Analyses for Outcome Measures in “Mindful Moms” Group Alone (Estimated Means and Standard Errors)

| Time point | Estimated mean | Estimated Δ from baseline | t | Adjusted p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 13.54 (0.40) | — | — | — |

| 6 weeks (midpoint) | 6.70 (0.79) | −6.85 (0.73) | −9.38 | <.0001 |

| 12 weeks (end) | 5.05 (0.67) | −8.49 (0.67) | −12.76 | <.0001 |

| 18 weeks (PP) | 5.95 (1.12) | −7.60 (1.10) | −6.90 | <.0001 |

| Time point | Estimated EPDS | Estimated Δ from baseline | t | Adjusted p |

| Baseline | 15.20 (0.86) | — | — | — |

| 6 weeks (midpoint) | 9.95 (0.75) | −5.24 (0.80) | −6.55 | <.0001 |

| 12 weeks (end) | 8.06 (0.71) | −7.13 (0.96) | −7.40 | <.0001 |

| 18 weeks (PP) | 7.28 (0.95) | −7.91 (1.32) | −6.01 | <.0001 |

| Time point | Estimated stress | Estimated Δ from baseline | t | Adjusted p |

| Baseline | 25.27 (0.89) | — | — | — |

| 6 weeks (midpoint) | 20.12 (1.14) | −5.15 (0.81) | −6.37 | <.0001 |

| 12 weeks (end) | 16.72 (1.17) | −8.55 (1.04) | −8.21 | <.0001 |

| 18 weeks (PP) | 14.72 (1.72) | −10.55 (1.72) | −6.13 | <.0001 |

| Time point | Estimated anxiety | Estimated Δ from baseline | t | Adjusted p |

| Baseline | 50.02 (2.10) | — | — | — |

| 6 weeks (midpoint) | 44.17 (2.03) | −5.85 (2.12) | −2.76 | .0296 |

| 12 weeks (end) | 36.04 (2.10) | −13.98 (2.92) | −4.78 | .0001 |

| 18 weeks (PP) | 32.85 (2.39) | −17.17 (3.37) | −5.09 | <.0001 |

| Time point | Estimated ruminations total | Estimated Δ from baseline | t | Adjusted p |

| Baseline | 26.63 (1.08) | — | — | — |

| 6 weeks (midpoint) | 23.23 (1.07) | −3.41 (0.99) | −3.42 | .0063 |

| 12 weeks (end) | 23.14 (1.29) | −3.49 (1.34) | −2.60 | .0462 |

| 18 weeks (PP) | 22.74 (1.45) | −3.89 (1.60) | −2.43 | .0669 |

| Time Point | Estimated MFAS total | Estimated Δ from baseline | t | Adjusted p |

| Baseline | 54.56 (2.51) | — | — | — |

| 6 weeks (midpoint) | 48.48 (2.28) | −6.08 (1.69) | −3.59 | .0037 |

| 12 weeks (end) | 43.97 (2.01) | −10.60 (1.96) | −5.40 | <.0001 |

| 18 weeks (PP) | 35.07 (3.30) | −19.49 (4.03) | −4.84 | .0001 |

Note. EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; MFAS = Maternal–Fetal Attachment Scale; PP = postpartum.

FIGURE 2.

Preliminary effects of time from baseline (Study Week 0) to postpartum (Study Week 18) in participants in the “Mindful Moms” group.

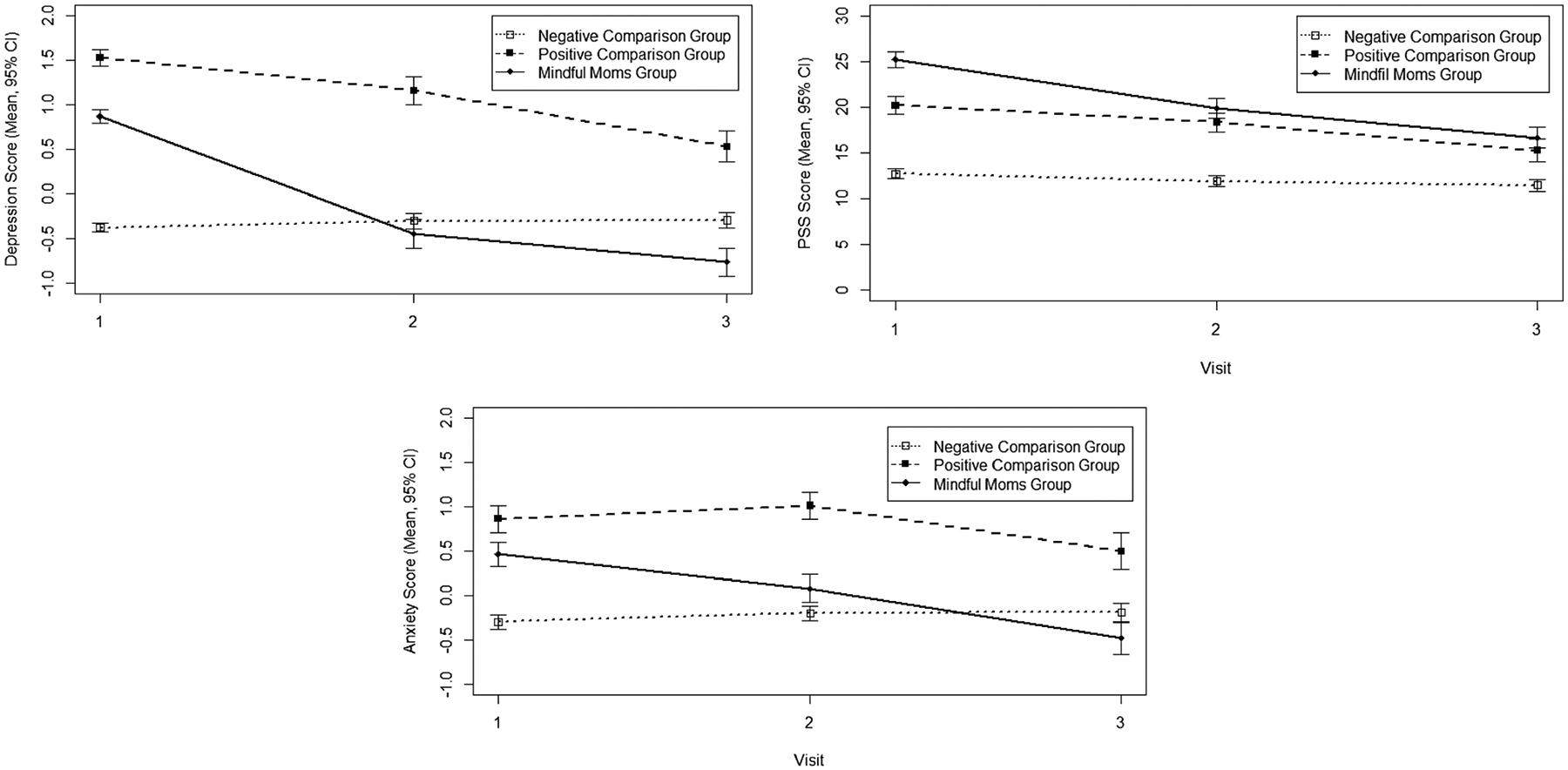

Differences Between Intervention and Usual Care

When comparing the three groups (“Mindful Moms” vs. positive comparison vs. negative comparison), with Bonferroni correction for post hoc tests, the model indicates that there were statistically significant interactions between the groups on depression symptoms (Group × Visit p value < .0001), perceived stress (Group × Visit p value < .0001), and state anxiety (Group × Visit p value < .0001), represented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Preliminary effects of time from baseline (Study Week 0) to postpartum (Study Week 18) on study outcomes of the “Mindful Moms” intervention.

Depression

In post hoc tests, statistically significant differences in the depressive symptoms change score over time were observed between the “Mindful Moms” group and the negative comparison group (−1.72, 0.19; p < .0001) and between the “Mindful Moms” group and the positive comparison group (−0.64, 0.24; p = .0270). Despite using the same threshold value for depressive symptoms, caution should be used in interpretation as the positive and negative comparison groups were assessed using the SCL versus the PHQ-9.

Stress

Significant differences in the stress (Perceived Stress Scale) change score over time were found between the “Mindful Moms” group and the negative comparison group (−7.35, 1.23; p < .0001) and between the positive comparison group and the negative comparison group (−3.68, 1.32; p = .0183). However, the comparison between the “Mindful Moms” group and the positive comparison group was not significantly different (−3.66, 1.59; p = .0690).

Anxiety

The only significant difference in the anxiety change score over time was between the “Mindful Moms” group and the negative comparison group (−1.06, 0.23; p < .0001).

DISCUSSION

A focus on adequate symptom management during pregnancy is an urgent clinical and research priority. In this longitudinal pilot study, we evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of the 12-week “Mindful Moms” intervention for pregnant women with depressive symptoms in preparation for future large-scale trials. Feasibility of enrollment and retention was supported by an enrollment rate of 82% and a retention rate of 66%. Qualitative data from participant interviews support acceptability of the intervention. Preliminary efficacy is supported in the finding of decreased levels of depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety, ruminations, and perinatal-specific depressive symptoms in the “Mindful Moms” intervention group over time. Areas for attention in rigorous future research trials are highlighted below.

Feasibility

An enrollment rate of 82% is encouraging for future large-scale studies. In-person recruitment at outpatient obstetric clinics and through community-based organizations and events were high-yield recruitment strategies (Rider et al., 2019). However, one barrier to higher enrollment was that, although many women expressed interest in the study, a significant minority (40%) was ineligible because they did not meet the depressive symptom severity threshold (≥10 on PHQ-9). This phenomenon requires future attention, as clearly many pregnant women self-identify as experiencing depression symptoms and are interested in using symptom self-management strategies. Future studies might consider expanding this inclusion criterion. It is also possible that the screening measure (PHQ-9) does not adequately measure distress in pregnancy, and another tool might be more appropriate. The PHQ-9 and the EPDS have both received support from ACOG for clinical screening purposes (ACOG, 2018); yet, research conducted with the EPDS has focused largely on the postpartum period. We recommend that future researchers consider appropriate screening tools for the enrollment of pregnant women with depressive symptoms.

Acceptability

A 66% retention rate is consistent with other studies evaluating behavioral and self-management interventions for this population. For example, a systematic review of the literature on yoga-based interventions for pregnant women found a retention rate ranging from 65% to 92% (Sheffield & Woods-Giscombé, 2016). In studies that required a threshold score of depressive symptoms as an inclusion criterion, retention ranged from 65% (Battle et al., 2015) to 82% (Muzik et al., 2012); neither of these studies included the racial and socioeconomic diversity of the current investigation. Importantly, qualitative feedback further supports acceptability of “Mindful Moms.” Participants were consistently positive about their experiences with the intervention, reporting that they appreciated the in-person, group-based format and the weekly check-ins by study staff to enhance accountability. Researchers should consider suggestions provided by participants, such as providing childcare and offering sessions in multiple locales.

Intervention Outcomes

Findings that depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety, and ruminations decreased over time among “Mindful Moms” participants are consistent with those of other studies with similar interventions. For example, an intervention conducted with nonpregnant women with depression yielded symptom improvement among women in the treatment group, with sustained effects evident at 1 year follow-up (Kinser et al., 2014). In addition, it is promising that our data highlight the preliminary efficacy of “Mindful Moms” in mitigating depressive symptom severity compared to an archival comparison group. It is perhaps not surprising that perceived stress was less amenable to change significantly with this brief intervention, considering the stress involved with becoming a mother. Of note, the decrease in ruminations experienced by those in the “Mindful Moms” group was most dramatic from baseline to the midpoint of the intervention and then leveled out by the end of intervention and at the postpartum assessment. It would be relevant to further evaluate the temporal nature of change in ruminations over time during pregnancy in a larger scale trial. Together, these findings may indicate the need to incorporate additional symptom self-management skills, such as cognitive reframing, time management, sleep hygiene, and self-care, to address the unique stress management needs of motherhood/new mothers.

There were three surprising findings of this study. First, the change scores of physical activity self-efficacy were not significantly different between groups or over time. In group-based physical activity studies involving motivational interviewing with nonpregnant populations, physical activity self-efficacy was enhanced (Barrett et al., 2018; Craike et al., 2019). It stands to reason that this measure may not be appropriate for women who have constantly shifting responsibilities and physical abilities during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. Another study of a different type of group-based gentle physical activity intervention during pregnancy also revealed no significant change over time in the Physical Activity Self-Efficacy Scale–Modified scores (Kinser et al., 2019). Few other studies have used this measure, so further research may be required in this area. Second, the maternal–fetal/child attachment scores, as measured by the MFAS, decreased over time during the study. One study of a mindful yoga intervention in pregnancy showed increases in MFAS scores over time that were independent of depressive symptom level (Muzik et al., 2012). Although our finding was unexpected, a careful review of the qualitative results suggests that participants most valued the intervention for the time allowed for self-care and enhancement of personal wellness. In fact, when asked directly about attachment, very few participants suggested a desire or need to enhance attachment, suggesting attachment may not be a relevant outcome. Third, there were no group differences in anxiety scores, even though anxiety and depressive scores are often correlated. However, despite being on the same measurement scale, the experimental and comparison groups completed different survey measures of anxiety.

Limitations

Several limitations must be addressed in future work. The sample size is somewhat small. However, given the pilot nature of the project, we were able to obtain important preliminary data that can contribute to modifications of the intervention and development of a future study with a larger sample. Generalizability of the findings is also somewhat limited because the “Mindful Moms” group was self-selecting without randomization to the intervention; thus, there may have been an expectation bias. Compared with the archival comparison group of pregnant women with depression (positive comparison), participants in “Mindful Moms” experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms. However, the comparison group did not have the same level of attention from study staff as did those in the “Mindful Moms” group, which may have been very important given the qualitative findings that participants valued study staff interactions. Future research should include randomization of larger samples to both treatment and active control groups. Also, despite regular staff meetings to discuss intervention fidelity and identify potential deviations from study protocols and intervention manuals, strict intervention fidelity measures were not applied (e.g., checklists for nurse discussions or video/audio recordings of yoga classes for fidelity to the protocol). This should be standardized in a future large-scale randomized clinical. Despite these limitations, however, this study represents an important first step, particularly given the diversity of the sample (63% Black/African American), and adds to the research on needs and preferences for self-management interventions for minority women.

Conclusion

The “Mindful Moms” intervention offers a feasible and easily sustainable therapeutic modality for pregnant women with depressive symptoms and warrants future large-scale investigation. Study findings suggest that women are not only interested in this type of intervention but also might benefit from improvements in depressive and related symptoms. The intervention provided opportunity for women to share experiences, which may have built a sense of social connectedness and belonging. In future studies, expansion of social connectedness to mitigate depressive symptoms should be explored, along with inclusion of participants experiencing subthreshold depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under Award R15HD086835 (PI: Kinser), the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation NARSAD Independent Investigator Grant (PI: York), the American Nurses Foundation Research Grant 5232 (PI: Kinser), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Award 5P60MD002256-06 (PI: York), and CTSA Award UL1TR002649 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr. Amstadter’s time is partially supported by NIAAA

K02-023239. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals for their important contributions to this study: Christine Aubry, RN, and Nastassya Russell, RN, in their roles as research assistants in the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing.

Footnotes

The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02953990; “Self-management of chronic depressive symptoms in pregnancy”).

The institutional review board at Virginia Commonwealth University approved the study (HM20006941). All participants provided written consent.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Patricia A. Kinser, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing, Richmond..

Leroy R. Thacker, Department of Biostatistics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond..

Amy Rider, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing, Richmond..

Sara Moyer, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing, Richmond..

Ananda B. Amstadter, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Richmond..

Suzanne E. Mazzeo, Department of Psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond..

Susan Bodnar-Deren, Department of Sociology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond..

Angela Starkweather, University of Connecticut School of Nursing, Storrs..

REFERENCES

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2015). ACOG Committee opinion no. 650: Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 126, e135–e142. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 757: Screening for perinatal depression. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 132, e208–e212. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Author. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett S, Begg S, O’Halloran P, & Kingsley M (2018). Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy can increase physical activity and improve health of adult ambulatory care patients in a regional hospital: The Healthy4U randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 18, 1166. 10.1186/s12889-018-6064-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle CL, Uebelacker LA, Magee SR, Sutton KA, & Miller IW (2015). Potential for prenatal yoga to serve as an intervention to treat depression during pregnancy. Womens Health Issues, 25, 134–141. 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean MK, Powell P, Quinoy A, Ingersoll K, Wickham EP 3rd, & Mazzeo SE (2015). Motivational interviewing targeting diet and physical activity improves adherence to paediatric obesity treatment: Results from the MI values randomized controlled trial. Pediatric Obesity, 10, 118–125. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2014.226.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsker D, Goldner EM, & Anderson E (2012). Supported self-management: A simple, effective way to improve depression care. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57, 203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JSL, & Thornicroft G (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 45, 11–27. 10.1017/S0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (1994). Perceived Stress Scale. www.mindgarden.com/docs/PerceivedStressScale.pdf

- Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craike M, Bourke M, Hilland TA, Wiesner G, Pascoe MC, Bengoechea EG, & Parker AG (2019). Correlates of physical activity among disadvantaged groups: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57, 700–715. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer H, Anheyer D, Lauche R, & Dobos G (2017). A systematic review of yoga for major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 70–77. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranley MS (1981). Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nursing Research, 30, 281–284. 10.1097/00006199-198109000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman RK, Hales DP, Sallis JF, Saunders R, Dunn AL, Bedimo-Rung AL, & Ring KB (2010). Validity of social-cognitive measures for physical activity in middle-school girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35, 72–88. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RA, Moore KM, & Bobo WV (2014). Treatment of nonpsychotic major depression during pregnancy: Patient safety and challenges. Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety, 6, 109–129. 10.2147/DHPS.S43308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans K, Spiby H, & Morrell JC (2020). Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce the symptoms of mild to moderate anxiety in pregnant women. A systematic review and narrative synthesis of women’s views on the acceptability of and satisfaction with interventions. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23, 11–28. 10.1007/s00737-018-0936-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL, & Mosher SW (1992). The Perceived Stress Scale: Factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14, 247–257. 10.1007/BF00962631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley RD, Brody DS, Engel M, Burke BL, Nordstrom K, Moralez E, Dickinson LM, & Emsermann C (2016). Motivational interviewing improves depression outcome in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 993–1007. 10.1037/ccp0000124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendig S, Keats JP, Hoffman MC, Kay LB, Miller ES, Simas TAM, Frieder A, Hackley B, Indman P, Raines C, Semenuk K, Wisner KL, & Lemieux LA (2017). Consensus bundle on maternal mental health: Perinatal depression and anxiety. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 62, 232–239. 10.1111/jmwh.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Bourguignon C, Taylor AG, & Steeves R (2013). “A feeling of connectedness”: Perspectives on a gentle yoga intervention for women with major depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34, 402–411. 10.3109/01612840.2012.762959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Bourguignon C, Whaley D, Hauenstein E, & Taylor AG (2013). Feasibility, acceptability, and effects of gentle hatha yoga for women with major depression: Findings from a randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27, 137–147. 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Elswick RK, & Kornstein S (2014). Potential long-term effects of a mind–body intervention for women with major depressive disorder: Sustained mental health improvements with a pilot yoga. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28, 377–383. 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Goehler LE, & Taylor AG (2012). How might yoga help depression? A neurobiological perspective. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 8, 118–126. 10.1016/j.explore.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Jallo N, Thacker L, Aubry C, & Masho S (2019). Enhancing accessibility of physical activity during pregnancy: A pilot study on women’s experiences with integrating yoga into group prenatal care. Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology, 6, 2333392819834886. 10.1177/2333392819834886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, & Masho S (2015a). “I just start crying for no reason”: The experience of stress and depression in pregnant, urban, African American adolescents and their perception of yoga as a management strategy. Women’s Health Issues, 25, 142–148. 10.1016/j.whi.2014.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, & Masho S (2015b). “Yoga was my saving grace”: The experience of women who practice prenatal yoga. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 21, 319–326. 10.1177/1078390315610554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Moyer S, Mazzeo S, York TP, Amstadter A, Thacker L, & Starkweather A (2020). Protocol for pilot study on self-management of depressive symptoms in pregnancy. Nursing Research, 69, 82–88. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Thacker LR, Lapato D, Wagner S, Roberson-Nay R, Jobe-Shields L, Amstadter A, & York TP (2018). Depressive symptom prevalence and predictors in the first half of pregnancy. Journal of Women’s Health, 27, 369–376. 10.1089/jwh.2017.6426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, & Williams C (2008). Prenatal yoga. Guidance for providers and patients. Advance for Nurse Practitioners, 16, 59–60, 62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapato DM, Moyer S, Olivares E, Amstadter AB, Kinser PA, Latendresse SJ, Jackson-Cook C, Roberson-Nay R, Strauss JF, & York TP (2018). Prospective longitudinal study of the pregnancy DNA methylome: The U.S. Pregnancy, Race, Environment, Genes (PREG) Study. BMJ Open, 8, e019721. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, & Holman H (2003). Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicines: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland J, Salisbury AL, Battle CL, Hawes K, Halloran K, & Lester BM (2011). Major depressive disorder during pregnancy and emotional attachment to the fetus. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 14, 425–434. 10.1007/s00737-011-0237-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motl RW, Dishman RK, Trost SG, Saunders RP, Dowda M, Felton G, Ward DS, & Pate RR (2000). Factorial validity and invariance of questionnaires measuring social-cognitive determinants of physical activity among adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine, 31, 584–594. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzik M, Hamilton SE, Lisa Rosenblum K, Waxler E, & Hadi Z (2012). Mindfulness yoga during pregnancy for psychiatrically at-risk women: Preliminary results from a pilot feasibility study. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 18, 235–240. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2019). Yoga: What you need to know. RetrievedOctober 9, 2020, from https://nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga

- Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Loke W, Yeo W-S, Lim DY, Chan HW, & Sim W-S (2019). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of yoga-based interventions for maternal depression during pregnancy. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 34, 8–12. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, Coppola E, & Gaynes BN (2019). Interventions to prevent perinatal depression. JAMA, 321, 588. 10.1001/jama.2018.20865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider A, Aubry C, Moyer S, & Kinser P (2019). Perspectives on successes and challenges in the recruitment and retention of pregnant women in a research study. Clinical Research, 33, 6–14. https://acrpnet.org/2019/09/19/perspectives-on-successes-and-challenges-in-the-recruitment-and-retention-of-pregnant-women-in-a-research-study/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer J, Dwan K, Lawlor DA, Greig CA, McMurdo M, Morley W, & Mead GE (2012). Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 7, CD004366. 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers BL, & Cowles KV (1993). The qualitative research audit trail: A complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing & Health, 16, 219–226. 10.1002/nur.4770160309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P, & Sawin KJ (2009). The individual and family self-management theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 57, 217–225.e6. 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing and Health, 23, 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield KM, & Woods-Giscombé CL (2016). Efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability of perinatal yoga on Women’s mental health and well-being: A systematic literature review. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 34, 64–79. 10.1177/0898010115577976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidebottom AC, Harrison PA, Godecker A, & Kim H (2012). Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9 for prenatal depression screening. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 15, 367–374. 10.1007/s00737-012-0295-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu AL (2016). Screening for depression in adults. JAMA, 315, 380–387. 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1983). Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tilton SR (2008). Review of the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). NewsNotes. [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr., Grossman DC, Kemper AR, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, & Wong JB (2019). Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 321, 580–587. 10.1001/jama.2019.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Yeung A, Li C, Wei GX, Chen KW, Kinser PA, Chan JSM, & Ren Z (2018). Effects of meditative movements on major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7, 195. 10.3390/jcm7080195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]