ABSTRACT

Background: Previous studies indicate that social functioning and resilience can mitigate the adverse psychological effects of interpersonal violence. Unfortunately, the role of these variables has not been studied in survivors of groups, organizations, and communities in which psychological abusive strategies are inflicted to recruit and dominate their members.

Objective: To examine the mediating role of social functioning and resilience in the relationship between psychological abuse experienced in the past while in a group and current psychosocial distress and psychopathological symptoms.

Method: In this cross-sectional study, an online questionnaire was administered to 794 English-speaking former members of different kinds of groups, such as religious, pseudo therapeutic, pyramid scheme groups, and others. Among them, 499 were victims of group psychological abuse and 295 were non-victims.

Results: Victims of group psychological abuse reported lower levels of social functioning and resilience than non-victims, and higher levels of psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms. Serial mediation analyses revealed that social functioning and resilience mediated part of the impact of group psychological abuse on psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms. Sex and age joining the group were included as covariates. Participants who had experienced higher levels of group psychological abuse tend to have poorer social functioning, which is related to lower resilience. In turn, lower levels of social functioning and resilience are related with higher distress.

Conclusions: This research sheds light on the underlying mechanisms involved in the relationship between group psychological abuse and distress suffered following this kind of traumatic experiences. Findings highlight the protective role of social adjustment, which can help promote and enhance resilience and mitigate psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms in survivors of group psychological abuse.

KEYWORDS: Cult survivors, distress, group psychological abuse, interpersonal trauma, psychological violence, resilience, social adjustment

HIGHLIGHTS

More severe abuse is associated with lower social functioning and resilience.

Lower social functioning and resilience are associated with higher distress.

Social functioning and resilience may be key aspects in fostering recovery for survivors of group psychological abuse.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: Estudios previos indican que la adaptación social y la resiliencia pueden mitigar los efectos psicológicos adversos de situaciones de violencia interpersonal. Desafortunadamente, no se ha estudiado aún el rol de estas variables en supervivientes de grupos, organizaciones y comunidades en las cuales se aplican estrategias de abuso psicológico para reclutar y dominar a sus miembros.

Objetivo: Examinar el rol mediador de la adaptación social y la resiliencia en la relación entre el abuso psicológico experimentado en un grupo en el pasado y el malestar psicosocial y síntomas psicopatológicos sufridos en la actualidad.

Método: Se diseñó un estudio transversal y se administró un cuestionario online a 794 personas de habla inglesa exmiembros de grupos de distinta naturaleza, como religiosos, pseudo terapéuticos, de estructura piramidal, u otros. De ellas, 499 fueron víctimas de abuso psicológico en grupo y 295 personas no fueron víctimas.

Resultados: Las víctimas de abuso psicológico en grupos reportaron menores niveles de adaptación social y resiliencia que las personas que no fueron víctimas, y mayores niveles de dificultades psicosociales y síntomas psicopatológicos. Los análisis de mediación en serie revelaron que la adaptación social y la resiliencia mediaron parte del impacto del abuso psicológico en las dificultades psicosociales y los síntomas psicopatológicos. El sexo y la edad de entrada al grupo fueron introducidos como covariantes. Los participantes que han experimentado mayores niveles de abuso psicológico en grupos tienden a tener menor funcionamiento social, lo que está relacionado con menor resiliencia. En consecuencia, menores niveles de funcionamiento social y resiliencia se relacionan con mayor malestar.

Conclusiones: Este estudio ayuda a comprender los mecanismos subyacentes implicados en la relación del abuso psicológico en grupos y el malestar sufrido después de este tipo de experiencias traumáticas. Los hallazgos resaltan la importancia del rol protector de la adaptación social, el cual puede ayudar a promover y mejorar la resiliencia y a mitigar las dificultades psicosociales y síntomas psicopatológicos en supervivientes de abuso psicológico en grupos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: supervivientes de sectas, malestar, abuso psicológico en grupos, trauma interpersonal, violencia psicológica, resiliencia, adaptación social

Short abstract

背景:先前研究表明, 社会功能和心理韧性可以减轻人际暴力的不利心理影响。不幸的是, 尚未在采用心理虐待策略来招募和支配其成员的团体, 组织和社区的幸存者中研究这些变量的作用。

目的:考查社会功能和心理韧性在过去在团体中经历的心理虐待与当前社会心理困扰和精神病理学症状之间的关系中的中介作用。

方法:在本横断面研究中, 对 794 名来自不同类型团体 (例如宗教, 伪治疗, 传销团体等) 的讲英语的前成员进行了在线问卷调查。其中, 团体心理虐待受害者499人, 非受害者295人。

结果:团体心理虐待的受害者报告的社会功能和心理韧性水平低于非受害者, 而心理社会困难和精神病症状水平更高。系列中介分析显示, 社会功能和心理韧性中介了团体心理虐待对社会心理困难和精神病症状的部分影响。加入该团体的性别和年龄作为协变量纳入。经历过较高程度团体心理虐待的参与者往往具有较差的社会功能, 这与较低的心理韧性有关。反过来, 较低水平的社会功能和心理韧性与较高的痛苦有关。

结论:本研究揭示了团体心理虐待与此类创伤经历后遭受的痛苦之间关系的潜在机制。研究结果强调了社会适应的保护作用, 这有助于促进和增强团体心理虐待幸存者的心理社会困难和心理病理症状。

关键词: 邪教幸存者, 痛苦, 团体心理虐待, 人际创伤, 心理暴力, 心理韧性, 社会适应

1. Introduction

There is a growing body of research indicating that positive social processes may promote more positive and adaptive coping in the management of traumatic experiences (Sippel, Pietrzak, Charney, Mayes, & Southwick, 2015), and may mitigate mental health disorders following interpersonal violence, such as intimate partner violence (Beeble, Bybee, Sullivan, & Adams, 2009), child abuse (Schumm, Briggs-Phillips, & Hobfoll, 2006), or war experiences (Wingo et al., 2017). However, little is known about the role of positive social processes regarding how survivors of social groups that are high-demand, manipulative, or abusive towards their members cope with trauma (e.g. Lalich & Tobias, 2006). As a first step in the exploration of this phenomenon, the purpose of this study was to examine how social functioning and resilience may influence distress suffered by survivors of group psychological abuse.

1.1. Group psychological abuse

Researchers have extensively documented psychologically abusive practices that may take place in group settings to recruit and retain followers (e.g. Coates, 2016; Rousselet, Duretete, Hardouin, & Grall-Bronnec, 2017; Saldaña, Antelo, Rodríguez-Carballeira, & Almendros, 2018).Group psychological abuse is defined as a process of systematic and continuous perpetration of pressure, control, manipulation, and coercion strategies that are inflicted on group members to achieve their submission (Rodríguez-Carballeira et al., 2015), their conformity to group norms and expectations (Coates, 2016), their obedience and compliance with group authority figures (Hassan & Shah, 2019), and their extreme dependency on the group. Group authority figures may take advantage of the control they have over victims of psychological abuse in order to obtain different personal benefits, such as financial resources, access to sexual relationships or ways of strengthening their power. Prior studies have classified the psychologically abusive behaviours that may occur in group settings into 26 strategies (Rodríguez-Carballeira et al., 2015), including isolation from family, manipulation of information, control of affective relationships, control over activities and time use, intimidation and threats, manipulation of guilt, denigration of critical thinking, and imposition of an absolute authority. In addition to these psychologically abusive behaviours, a small number of victims also experience physical or even sexual abuse in the group (e.g. Boeri, 2002; Lalich & Tobias, 2006; Malinoski, Langone, & Lynn, 1999).

Evidence shows that group psychological abuse occurs in groups, organizations, and communities of different shape, size, and with many variations in beliefs, practices, and social customs (Lalich & Tobias, 2006). Thus, psychological abuse has been reported by former members of religious, political, philosophical, pseudo-therapeutic, personal development, and pyramid scheme groups, among others. The limited existing data on the prevalence of this phenomenon indicate that there are at least 5,000 groups in which psychological abuse is perpetrated operating in the United States and Canada with a combined membership of over 2,500,000 people (McCabe, Goldberg, Langone, & DeVoe, 2007). However, prevalence data should be approached with caution as many abusive groups often go undetected. The human and clinical relevance of this phenomenon stems from its negative consequences for the victims, their relatives, and society as a whole.

1.2. Distress in survivors of group psychological abuse

The recovery process of survivors of group psychological abuse and the way they cope with trauma can be very diverse, as is also the case for victims of other forms of interpersonal violence. Most survivors describe having gone through a difficult period of readjustment to society outside the group (e.g. Coates, 2010; Durocher, 1999; Lalich & Tobias, 2006). In their own words, they describe feeling like ‘Martians’ (Boeri, 2002, p. 338), feeling ‘out of place’ (Coates, 2010, p. 306), or even perceiving the outgroup society as ‘a strange and scary new world’ (Matthews & Salazar, 2014, p. 198). Furthermore, some victims of group psychological abuse may have been born or raised within the group, generally experiencing a more significant loss, and facing additional readjustment challenges when leaving the group (Gibson, Morgan, Wooley, & Powis, 2011; Kendall, 2016; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). However, some victims face this readjustment with a more positive perspective, feeling relieved by not being in the group and enjoying making decisions on their own and being masters of their personal life (Durocher, 1999; Kendall, 2016).

Regarding the negative outcomes of group psychological abuse, evidence shows that survivors may experience psychological and social difficulties (Saldaña et al., 2018), psychopathological symptoms (Gasde & Block, 1998; Goldberg, Goldberg, Henry, & Langone, 2017; Malinoski et al., 1999), and impairment in general well-being (Saldaña, Rodríguez-Carballeira, Almendros, & Guilera, 2021), even many years after they have left the group (Aronoff, Lynn, & Malinoski, 2000). Psychosocial difficulties frequently reported by survivors include feelings of loss, anger, guilt, low self-esteem, decision-making difficulties, and social skill deficits. Psychopathological symptoms usually found in this population include depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and dissociation. A growing body of research shows that the degree of group psychological abuse experienced predicts severity of distress (e.g. Göransson & Holmqvist, 2018). Previous studies have explored the mediator role of post-involvement stressful life events in the relationship between group psychological abuse and psychopathological symptoms (Saldaña et al., 2021). However, protective factors such as social functioning or resilience that could mediate the relationship between group psychological abuse and distress still need to be explored.

1.3. The role of social functioning when coping with trauma

Social functioning defines how people interact with their environment and their ability to fulfill various roles in different social settings such as work, social activities, and relationships with partners, family, and friends (Bosc, Dubini, & Polin, 1997). Survivors of group psychological abuse may also experience limitations in their social functioning after leaving the group, as do victims of intimate partner violence (e.g. McCaw, Golding, Farley, & Minkoff, 2007). The socialization process that takes place within an abusive group has been compared with those identified in total institutions (Goffman, 1961), and usually involves isolation, intensive interaction with other members of the group, breaking up with the past, creating false identities, and restrictions on personal life (Boeri, 2002; Coates, 2010; Hassan & Shah, 2019). While members are in the group their social network is drastically reduced, as they are encouraged to distance themselves from their family and friends (Rousselet et al., 2017). Some members are also encouraged to stop studying or working and to dedicate most of their time and life to the group, and even their daily life decisions such as who to relate to or what to do in their free time can be controlled by the group (Lalich & Tobias, 2006; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). Thus, most survivors face significant social challenges after leaving the group as they seek to ‘get their life back’ (Kendall, 2016; Matthews & Salazar, 2014; Rousselet et al., 2017).

Prior studies have analysed the relationship between social functioning and distress in clinical populations and also in victims of different traumatic experiences. On the one hand, impairment in social functioning has been associated with more symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression, or physical health problems (e.g. Bosc, 2000; Wingo et al., 2017). On the other hand, social adjustment and supportive relationships also seem to serve as protective factors, decreasing the likelihood of developing mental health problems (e.g. Beeble et al., 2009; Coker, Watkins, Smith, & Brandt, 2003). Among the different pathways leading from social functioning to less distress, evidence shows that resilience has an important role. Resilience is defined as the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress (American Psychological Association, 2012). It is a multidimensional construct which entails features such as self-efficacy, tolerance of negative affect, adaptability to change, secure relationships, and a realistic sense of control (Connor & Davidson, 2003). Several studies on victims of traumatic experiences have suggested that good quality social relationships and an adequate level of social functioning contribute to resilience, and, in turn, decrease mental health problems (e.g. Collishaw et al., 2016; Howell, Thurston, Schwartz, Jamison, & Hasselle, 2018; Machisa, Christofides, & Jewkes, 2018). Thus, to understand the negative consequences of interpersonal violence it seems critical to examine how social functioning can be affected by the abusive experience and, in turn, how that can affect resilience. Although these associations have been already studied in intimate partner violence, child abuse, or in other populations such as war veterans, to our knowledge, they have not yet been studied in survivors of group psychological abuse.

1.4. Research objectives

The main objective of the present study was to contribute to the understanding of the adverse consequences of group psychological abuse by documenting its impact on psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms by exploring social functioning and resilience as potential serial mediators (Figure 1). The model we are proposing describes possible relations between these variables drawing on previously published evidence. The nature of the psychological abuse practices that take place in groups lead to the group itself becoming the centrepiece in the lives of its members, impeding and damaging their social relations, support networks and other social resources outside the group itself. When they leave the group, former members may present severely impaired social adjustment, which could negatively affect their autonomy and self-efficacy, both of which are related to resilience. Finally, poor social functioning and resilience can exacerbate the suffering experienced by survivors of group psychological abuse. Thus, we have specified the following hypotheses:

Victims of group psychological abuse (vs. non-victims) will report lower levels of social functioning and resilience, but higher levels of distress;

Experienced group psychological abuse will correlate negatively with social functioning and resilience;

Social functioning and resilience will be positively correlated and will correlate negatively with distress;

Social functioning and resilience will serially mediate the relationship between experienced group psychological abuse and distress.

Figure 1.

Proposed model concerning the relationship between group psychological abuse and distress: social functioning and resilience as mediators

2. Method

2.1. Procedure and participants

The study was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Barcelona. Data were collected through an online questionnaire using convenience non-probabilistic and snowball sampling methods. Survey responses were collected online using Qualtrics and the study was announced through victims’ associations, organizations providing information, education and counselling about group psychological abuse, health professionals, and on social media. Every participant received information regarding the study’s objectives, gave their informed consent, and participated anonymously without compensation. Participants were asked to report their experiences in a group they had been members of in the past and that they no longer belonged to when the study took place. If they had belonged to more than one group, they were asked to select the group in which they were most involved. We provided our email address in case they needed support or wished to receive further information.

The sample consisted of 794 participants (Sex: 67.1% women, 31.5% men; Age: M = 49.5, SD = 15.8). All participants were English-speaking, and they were mainly from the United States (76.3%), while a smaller percentage was from Europe (12.6%) or from Canada, and other western countries (11.1%). Participants were self-identified as former members of different groups, including religious (61.3%), personal growth or therapeutic (11.1%), cultural or leisure (9.6%), political (4.8%), humanitarian (3.3%), or pyramid scheme (3.1%) groups, among others. The age in which participants entered the group ranged from 0 to 66 (M = 19, SD = 16.4), the length of group membership was 14.8 years on average (SD = 12.5), and time passed since participants left the group was 15.7 years on average (SD = 13.5).

Participants were separated into two subsamples according to whether they had experienced psychological abuse in the group they selected. To divide the participants, we used the optimal cut-off point on a scale measuring experiences of group psychological abuse (see ‘Measures’ section). A first sample included 499 victims of group psychological abuse, and a second sample included the remaining 295 non-victims. Table 1 shows the main descriptive data of the sociodemographic and group-related information for each sample, including the comparisons between the sample of victims and the sample of non-victims.

Table 1.

Descriptive data of the samples of victims and non-victims

| Total sample | Victims | Non-victims | Comparisons |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics | Effect size | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 31.5% | 31.9% | 30.8% | χ2 = 6.85 | V = .09 |

| Women | 67.1% | 65.9% | 69.2% | ||

| Other | 1.4% | 2.2% | 0% | ||

| Age | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 49.5 (15.8) | 47.1 (14.5) | 53.7 (17) | t = 5.64 | d = .43 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Primary education | 7% | 7.2% | 6.5% | χ2 = 2.80 | V = .06 |

| Secondary education | 22.6% | 20.7% | 25.9% | ||

| University | 70.4% | 72% | 67.7% | ||

| Job status | |||||

| Student | 5.6% | 6.8% | 3.4% | χ2 = 71.15 | V = .30 |

| Unemployed | 12.8% | 11.7% | 14.6% | ||

| Full time work | 41.1% | 48.1% | 29.3% | ||

| Part time work | 16.1% | 18.1% | 12.6% | ||

| Pensioner | 24.5% | 15.3% | 40.1% | ||

| Age joining the group | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 19 (16.4) | 13.9 (13.8) | 27.8 (16.8) | t = 12.03 | d = .93 |

| Years inside the group | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.8 (12.5) | 17.3 (12.5) | 10.6 (11.3) | t = −7.79 | d = −.55 |

| Years outside the group | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 15.7 (13.5) | 15.9 (12.9) | 15.4 (14.5) | t = −.49 | d = −.03 |

| Group nature | |||||

| Religious | 61.3% | 77% | 34.9% | χ2 = 138.18 | V = .42 |

| Non-religious | 38.7% | 33% | 65.1% | ||

| Method of leaving | |||||

| Personal reflection | 56.9% | 63.9% | 45.1% | χ2 = 101.14 | V = .36 |

| Counselled | 7.2% | 9.8% | 2.7% | ||

| Expelled/Dissolution | 21.4% | 20.8% | 22.4% | ||

| Other (e.g. life change) | 14.5% | 5.4% | 29.8% | ||

| Group psychological abuse | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 62.7 (45.9) | 95 (21.9) | 8.2 (11.1) | t = −73.85 | d = −4.65 |

Total sample n = 794. Victims: n = 499. Non-victims: n = 295. χ2 = Pearson chi-square test. V = Cramer’s V. t = Student’s t test. d = Cohen’s d. All chi-square tests and t tests were significant at p < .05, except in ‘educational level’ (p = .24) and ‘years outside the group’ (p = .62). Group psychological abuse = measured through the Psychological Abuse Experienced in Groups Scale.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Group psychological abuse

We used the Psychological Abuse Experienced in Groups Scale (PAEGS; Saldaña, Rodríguez-Carballeira, Almendros, & Escartín, 2017) to assess the degree of group psychological abuse experienced while in the group. It is a self-report questionnaire composed of 31 Likert-type items ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (continually). An example item states, ‘They tried to make me spend as much time as possible with the group’. A total score was calculated by adding the items and the theoretical range of the scale scores is from 0 to 124. A score above 39 has been found to be useful as a threshold for detecting group psychological abusive experiences in an English-speaking population, with a sensitivity of 94.1% and a specificity of 95.3% (Saldaña, Antelo, & Rodríguez-Carballeira, 2020). This empirical criterion was used to classify participants in the current study into a sample of victims and a sample of non-victims. PAEGS has demonstrated good internal consistency, and convergent and discriminant validity. In the current study, McDonald’s Omega coefficient for the overall score was ω = .99.

2.2.2. Social functioning

The Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale (SASS; Bosc et al., 1997) was used to explore the areas of work and leisure, family and extrafamilial relationships, intellectual interests, satisfaction in roles, and self-perception regarding the ability to manage and control the environment. It contains 21 Likert-type items with four response categories, with 0 indicating low social adjustment and 3 indicating high social adjustment. Items include ‘How – in general – do you rate your relationships with other people?’ and ‘To what extent are you involved in community life (such as club, church, etc.)?’ A total score is computed by adding the items. The original study reported adequate psychometric properties in terms of internal structure, reliability, and external validity evidenced by correlations with psychological distress. In the current study, McDonald’s Omega coefficient was ω = .88.

2.2.3. Resilience

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC; Campbell‐Sills & Stein, 2007) was used to assess the ability to cope with adversity. It is composed of 10 items ranged on a 5-point scale from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time), with a score ranging from 0 to 40. An example item states, ‘I am not easily discouraged by failure’. The CD-RISC is a widely used scale with excellent psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, reliability, and validity in different cultures. In our sample we found an adequate internal consistency coefficient (ω = .94).

2.2.4. Distress

The Inventory of Psychosocial Difficulties in survivors of Abusive Groups (IPD-AG; Antelo, Saldaña, Guilera, & Rodríguez-Carballeira, 2021) was used to assess the specific psychological and social distress that survivors of group psychological abuse can suffer since they left the group. It is a self-report questionnaire composed of 32 Likert-type items (0 = not at all; 1 = a little bit; 2 = moderately; 3 = quite a bit; 4 = extremely). Items include ‘Regret for things I did in the group, later considered inappropriate’ and ‘Distress about having wasted an important time in my life by being in the group’. The IPD-AG distinguishes four types of difficulties: emotional difficulties, cognitive difficulties, relational and social integration difficulties, and other specific problematic behaviours. The original study has shown good internal consistency and convergent validity. In this study, we considered the overall score and the four dimensions of the scale. McDonald’s Omega coefficient for the total score was .99, ranging from .91 to .97 in the four dimensions.

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983) was used to evaluate current psychopathological symptoms. It is composed of 53 Likert-type items ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), with higher mean scores indicating a greater degree of psychopathological symptoms. In this study, we considered Global Severity Index and the nine psychopathological dimensions. The BSI has demonstrated high internal consistency and construct validity in a variety of samples, including victims of different abusive contexts. In the present study, evidence of internal consistency was found for the Global Severity Index (ω = .99) and for the nine dimensions (ω = .92-.96).

2.3. Analysis plan

To test Hypothesis 1, independent sample t tests were computed to explore the differences between the samples of victims and non-victims on social functioning, resilience, and distress measures. Effect sizes were obtained computing Cohen’s d. To test Hypotheses 2 and 3, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the correlations between group psychological abuse, social functioning, resilience, and distress measures. To test Hypothesis 4, we conducted two serial mediation analyses using the PROCESS 3.5 Macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2017; Model 6). We assessed the indirect effect of group psychological abuse on psychosocial difficulties and on psychopathological symptoms through social functioning and through both social functioning and resilience. The 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect was obtained with 10,000 bootstrap resamples, and unstandardized and standardized coefficients were reported. Mediated effects are statistically significant when the coefficient’s confidence interval does not contain zero (Hayes, 2017). Preliminary analyses showed that sex and age joining the group were associated with psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms. Therefore, these variables were included as covariates. For all the hypotheses and their respective analyses, a p value lower than .05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses

In order to test Hypothesis 1, we examined the scores of social functioning, resilience, and distress measures. As predicted, comparisons of means between the samples of victims and non-victims showed significant differences on all scales (Table 2). Victims of group psychological abuse reported lower levels of social functioning (t792 = −5.34, p < .001, d = −.39) and resilience (t792 = −3.36, p = .001, d = −.25), with small effect sizes, and higher levels of psychosocial difficulties (t791,06 = 42.53, p < .001, d = 2.74) and psychopathological symptoms (t790,34 = 21.21, p < .001, d = 1.39), with large effect sizes. Regarding the dimensions of psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms, consistent results were found when examining them separately (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). The dimensions with the largest differences were Emotional Difficulties (d = 2.97) and Relational Difficulties (d = .2.44) on the psychosocial difficulties measure, and Paranoid ideation (d = 1.43) and Obsessive-Compulsive (d = 1.39) on the psychopathological symptoms measure.

Table 2.

Descriptive data and correlations between measures

| Victims |

Non-Victims |

Comparisons |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t | d | ||||

| Social functioning | 36.68 (8.57) | 40.04 (8.55) | −5.34*** | −.39 | |||

| Resilience | 25.72 (7.98) | 27.69 (7.94) | −3.36** | −.25 | |||

| Psychosocial difficulties | 6.57 (28.48) | 9.08 (16.23) | 42.53*** | 2.74 | |||

| Psychopathological symptoms | 1.54 (.95) | .38 (.59) | 21.21*** | 1.39 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1. Group psychological abuse | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 2. Social functioning | −.19*** | - | - | - | - | ||

| 3. Resilience | −.09** | .57*** | - | - | - | ||

| 4. Psychosocial difficulties | .84*** | −.32*** | −.25*** | - | - | ||

| 5. Psychopathological symptoms | .59*** | −.42*** | −.37*** | .79*** | - | ||

Total sample: n = 794. Victims: n = 499. Non-victims: n = 295.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

3.2. Correlational analysis

In order to test Hypotheses 2 and 3, we examined the correlations of all the main measures of the study (Table 2). As expected, group psychological abuse was negatively associated with social functioning (r = −.19, p < .001) and resilience (r = −.09, p = .009) with small strength. Likewise, group psychological abuse was positively and strongly related to psychosocial difficulties (r = .84, p < .001) and psychopathological symptoms (r = .59, p < .001). Social functioning and resilience were negatively associated with distress measures with medium strength. In addition, we found a strong positive association between social functioning and resilience (r = .57, p < .001). Consistent results were found when analysing the associations between the nine dimensions of distress and social functioning and resilience (see Table S2).

3.3. Serial mediation analyses

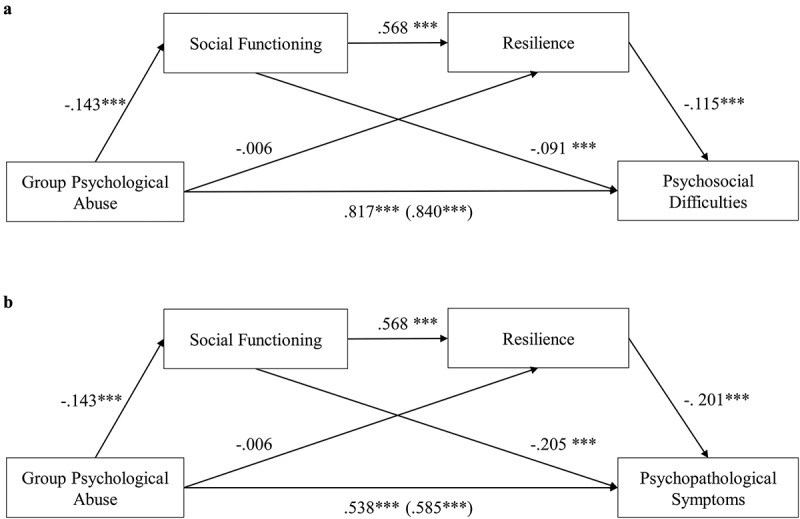

In order to test Hypothesis 4, we conducted independent serial mediation analyses. Results provided support for the hypothesized sequential model, which revealed how the association between group psychological abuse and distress measures was found to be influenced by both social functioning and resilience while controlling for sex and age joining the group. As Figure 2 and Table 3 show, participants who suffered a higher degree of group psychological abuse report lower levels of social functioning, and consequently, lower levels of resilience and higher levels of psychosocial difficulties (Figure 2a) and psychopathological symptoms (Figure 2b). Regarding sex and age joining the group as control variables, men reported higher levels of social functioning (f1 = 2.07, p = .002) and lower levels of psychosocial difficulties (g1 = −3.85, p = .02). Furthermore, people who joined the group at a younger age reported lower levels of social functioning (f3 = .059, p = .005). The overall regression models predicting psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms explained 74% and 48% of the total variance, respectively.

Figure 2.

Serial mediation models: social functioning and resilience mediating the association between group psychological abuse and distress

Values shown are standardized coefficients. Total effect of Group Psychological Abuse is shown in parenthesis. Covariates were sex and age joining the group but are not represented here. Panel A: Serial mediation model predicting Psychosocial Difficulties. Panel B: Serial mediation model predicting Psychopathological Symptoms. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Table 3.

Model coefficients of serial mediation analyses

| Consequent |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | Y1 | Y2 | |||

| Antecedent | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | Coefficient (SE) | ||

| X | a | −.027 (.007) *** | −.001 (.005) | c’ | .728 (.018) *** | .012 (.001) *** |

| M1 | d | - | .523 (.027) *** | b1 | −.429 (.111) *** | −.023 (.003) *** |

| M2 | - | - | b2 | −.587 (.121) *** | −.025 (.004) *** | |

| C1 | f1 | 2.07 (.653) ** | .914 (.518) | g1 | −3.85 (1.70) * | .043 (.059) |

| C2 | f2 | −.069 (3.32) | 4.25 (1.70) * | g2 | 2.58 (5.01) | −.115 (.193) |

| C3 | f3 | .059 (.021) *** | −.018 (.015) | g3 | .021 (.049) | −.001 (.001) |

| constant | i1 | 37.85 (.77) *** | 6.67 (1.16) *** | i2 | 38.40 (4.31) *** | 1.93 (.161) *** |

| R2 = .06 | R2 = .33 | R2 = .74 | R2 = .48 | |||

| F4, 789 = 13.07*** | F5, 788 = 79.89*** | F6, 787 = 657.43*** | F6, 787 = 208.90*** | |||

n = 794. Coefficient = unstandardized regression coefficients. X = Group psychological abuse. M1 = Social functioning. M2 = Resilience. C1 = Sex: Men vs Women and Other. C2 = Sex: Other vs Women and Men. C3 = Age joining the group. Y1 = Psychosocial difficulties. Y2 = Psychopathological symptoms.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

As predicted, the total indirect effect of group psychological abuse through social functioning and resilience on distress measures was significant (Psychosocial difficulties: standardized beta = .009, SE = .003, 95% CI [.004, .025]; Psychopathological symptoms: standardized beta = .016, SE = .005, 95% CI [.007, .027]). Furthermore, there was a significant indirect path from group psychological abuse to distress measures only through social functioning (Psychosocial difficulties: standardized beta = .013, SE = .005, 95% CI [.004, .024]; Psychopathological symptoms: standardized beta = .029, SE = .009, 95% CI [.013, .049]). Note that there was no significant path from group psychological abuse to resilience, and there was also no indirect effect of group psychological abuse on distress measures through resilience (Psychosocial difficulties: standardized beta = .001, SE = .004, 95% CI [−.006, .008]; Psychopathological symptoms: standardized beta = .001, SE = .006, 95% CI [−.011, .014]). The direct effect of group psychological abuse on psychosocial difficulties (c’ = .75, p < .001) and psychopathological symptoms (c’ = .013, p < .001) remained significant after including the mediators.

Consistent results were found when examining each dimension of the psychosocial difficulties and the psychopathological symptoms measures (Table S3) separately. Interestingly, different levels of explained variance were found among the dimensions’ models. Regarding psychosocial difficulties, although the overall regression model explained the highest level of variance in Emotional Difficulties (77%), this seems to be mainly due to the influence of group psychological abuse. In comparison, social functioning and resilience seem to predict more Relational Difficulties and Cognitive Difficulties, respectively. Regarding psychopathological symptoms, the overall regression models which explained the highest levels of variance were in Obsessive-Compulsive symptoms (49%), Depression (48%), Interpersonal sensitivity (47%), Paranoid ideation (46%) and Psychoticism (45%). Focusing on the indirect effects, a pattern similar to the overall scores of psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms emerged for every dimension.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the relationship between experiences of group psychological abuse, and social functioning, resilience, and distress after leaving a high-demand, manipulative, or abusive group. Focusing on the differences between the sample of victims and non-victims, as predicted, victims of group psychological abuse reported higher levels of psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms in comparison to non-victims, which is consistent with previous findings (e.g. Aronoff et al., 2000; Göransson & Holmqvist, 2018; Saldaña, Antelo, Almendros, & Rodríguez-Carballeira, 2019). Victims of group psychological abuse also reported lower levels of social functioning and resilience in comparison to non-victims. Furthermore, results revealed that social functioning and resilience were positively interrelated and negatively related to group psychological abuse. This is consistent with the fact that victims of group psychological abuse usually suffer continuous emotional abuse and control of their personal life, and are gradually isolated from outside influences, cutting their personal, professional, and family ties (Rodríguez-Carballeira et al., 2015). In consequence, after leaving the group, their social networks and even the way they relate to other people might have been affected (Coates, 2010; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). People who have experienced group psychological abuse are likely to undergo a difficult adjustment period, having to face emotional and social challenges, even long after the abusive experience has remitted. In this regard, victims of group psychological abuse may perceive environmental demands as more stressful (Saldaña et al., 2021), frequently expressing a feeling of failure in achieving life goals and feeling confused and lost (Lalich & Tobias, 2006; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). These findings suggest that, in addition to just negatively affecting mental health and well-being, group psychological abuse also affects a person’s subsequent adjustment to society and their way of dealing with the experience of trauma and daily sources of stress.

Correlational analyses also showed that social functioning and resilience were negatively related to distress measures. Thus, as is the case for victims of other types of interpersonal violence (e.g. Howell et al., 2018; Machisa et al., 2018; Wingo et al., 2017), among survivors of group psychological abuse it seems that being better adjusted to society, and having good quality relationships and positive coping skills, might be protective factors against further distress. Furthermore, serial mediation analyses revealed that the association between group psychological abuse and distress was partially mediated by social functioning and resilience. In particular, the paths ‘group psychological abuse → social functioning → distress’ and ‘group psychological abuse → social functioning → resilience → distress’ were significant. These findings are similar to those seen in intimate partner violence settings, indicating that psychological abuse may influence poor mental health by undermining social and personal resources (e.g. Beeble et al., 2009; McCaw et al., 2007). Interestingly, although results of correlational analyses showed that group psychological abuse is negatively correlated with resilience; serial mediation analyses showed that the severity of the abuse did not directly predict resilience. Therefore, survivors’ social resources and the quality of their relationships may have greater influence on their ability to cope with the traumatic experience and daily sources of stress than the intensity of the group psychological abuse they suffered. However, it is important to note that other studies have shown that resilience may also promote social functioning, or more likely, that a complex bidirectional relationship exists between them (e.g. Silverman, Molton, Alschuler, Ehde, & Jensen, 2015). Furthermore, experiencing distress may also lead to lower social functioning over time, since passivity, anxiety, lack of social skills, and other difficulties could decrease people’s ability to achieve social integration and elicit favourable attitudes from others (e.g. Bosc et al., 1997; Tsai, Harpaz-Rotem, Pietrzak, & Southwick, 2012). It would be beneficial for future researchers to explore these alternative paths between social functioning, resilience, and distress in this specific population of victims.

Focusing on the covariates included in the mediation analyses, results showed that sex and the age at which the group was joined did not directly predict distress after leaving the group, but social functioning did. Regarding sex, being a woman was associated to lower levels of social functioning, which could be due to additional difficulties because of the patriarchal stratification system and a more limited access to resources (Boeri, 2002; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). In addition, researchers have documented that groups where group psychological abuse might be inflicted generally follow a patriarchal structure and rigid gender roles (Boeri, 2002; Lalich & Tobias, 2006). In consequence, women may find it more difficult to adjust to society due to greater subjugation and dependence while in the group. On the other hand, joining the group at an earlier age was also associated with lower levels of social functioning. Survivors who were born or raised within the group might have been exposed to group psychological abuse for all or a large part of their life. Thus, they were usually encouraged to only relate with other members and socialize within the group. In consequence, their loss can be much more significant, leaving behind in the group their family, friends and even their way of life (Gibson et al., 2011; Kendall, 2016; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). Most of them also report feeling left behind in education, employment, or management of daily problems, feeling lost, confused, and different from others around them (Gibson et al., 2011; Matthews & Salazar, 2014).

Finally, focusing on distress, serial mediation analyses suggested that victims who experienced higher levels of psychological abuse and are also less socially well-adjusted and resilient, may suffer with greater intensity specific psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms. Therefore, survivors might feel inferior to others, extremely lonely or even paranoid and suspicious, having difficulties when relating with other people and fear that they may reject them (e.g. Coates, 2010; Matthews & Salazar, 2014). In addition, they might experience other cognitive problems, such as difficulties in making their own decisions or thinking clearly, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and psychoticism (e.g. Gasde & Block, 1998; Saldaña et al., 2021). Likewise, victims of group psychological abuse frequently suffer symptoms of depression and a wide range of emotional difficulties particularly related with the group psychological abuse experienced (e.g. Malinoski et al., 1999; Saldaña et al., 2019). In this line, it is important to note that a direct effect was found in group psychological abuse to psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms even after controlling for social functioning and resilience. Interestingly, it has been argued that this distress is a consequence of a major life transition and reflects a predictable response as a result of leaving a social group and subsequent problems readjusting to society (e.g. Coates, 2016). However, our results suggest that group psychological abuse is the main variable that influences later distress, while social functioning and resilience play a fundamental role in mitigating psychosocial difficulties and psychopathological symptoms.

4.1. Clinical implications

The present findings have important implications for the assessment and treatment of survivors of group psychological abuse. In the first place, this study highlights the importance of social adjustment for fostering recovery from the abusive experience. Victims of group psychological abuse often report that they would have wished for more information and support to develop daily life skills, such as job hunting or communication skills (Durocher, 1999), especially those born and/or raised within the group (Matthews & Salazar, 2014). In this sense, counsellors could help survivors to improve their social functioning through basic life skills training, encouraging educational and career plans, and learning relationship skills. Furthermore, support groups with other victims of group psychological abuse may help them express and process their traumatic experience and improve their social skills without fear of being judged or misunderstood (Goldberg et al., 2017; Lalich & Tobias, 2006).

On the other hand, enhancing adaptive and positive coping strategies seems to be another key aspect in fostering recovery. After the abusive experience, victims of group psychological abuse may feel disoriented and immobilized and have difficulties taking everyday decisions and living autonomously due to their past subjugation to and dependence on the group (Durocher, 1999; Kendall, 2016). Counsellors should promote self-confidence and self-efficacy, encouraging survivors to see the experience as a process of growth and promoting their personal autonomy. Thus, effective interventions will need to focus on a wide range of factors, including the abusive experience characteristics, the circumstances of the survivors such as sex or the age joining the group, and the promotion of social functioning and resilience.

4.2. Limitations and future directions

This study’s findings should be evaluated in the light of several limitations. Regarding generalizability, we used a convenience sample composed of a higher proportion of women and former members of religious groups who have been out of the group for a long time. Since survivors of group psychological abuse are a hard-to-reach hidden population, it was not possible to use a probabilistic sampling method and the representativeness of our sample could not be verified. Second, differences in demographic and group-related variables between the samples of victims and non-victims indicate that our conclusions should be approached with caution. Additional research with more diverse and equivalent samples, and with people who have left the group recently, is necessary to better understand the relationships between group psychological abuse, social functioning, resilience, and distress. Third, the cross-sectional design of the study implies that no causality can be inferred from the results of the mediation analyses. Even though group psychological abuse and distress measures were completed addressing different time frames (i.e. when they were in the group and the week prior to participating in the study, respectively), no time frame was specified for social functioning and resilience measures. Further studies should implement longitudinal designs to examine alternative paths between those variables, for example analysing if distress might be affecting social functioning and resilience at the same time. Finally, some variables that might be seen to have relevant influence on the examined associations were not included in the study, such as group-based physical and sexual abuse, psychosocial support, and counselling received. Researchers should examine the impact of these variables to better understand the long-term consequences of group psychological abuse.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Spain, under Grant PSI2016-75915-P, AEI/ FEDER, EU. Principal investigators: Álvaro Rodríguez-Carballeira and Jordi Escartín. Emma Antelo is the recipient of fellowship 2018FI-B2-00004 from the Agency for University and Research Grant Management, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain. Omar Saldaña is a Serra Hunter Lecturer.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due that it contains information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Barcelona (reference number: IRB00003099). Every participant received information regarding the study’s objectives, gave their informed consent, and participated anonymously without compensation.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- American Psychological Association . (2012). The road to resilience: What is resilience. Author. https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience [Google Scholar]

- Antelo, E., Saldaña, O., Guilera, G., & Rodríguez-Carballeira, A. (2021). Psychosocial difficulties in survivors of group psychological abuse: Development and validation of a new measure using classical test theory and item response theory. Psychology of Violence, 11(3), 286–12. doi: 10.1037/vio0000307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, J., Lynn, S. J., & Malinoski, P. (2000). Are cultic environments psychologically harmful? Clinical Psychology Review, 20(1), 91–111. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00093-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeble, M. L., Bybee, D., Sullivan, C. M., & Adams, A. E. (2009). Main, mediating, and moderating effects of social support on the well-being of survivors of intimate partner violence across 2 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 718. doi: 10.1037/a0016140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri, M. W. (2002). Women after the utopia: The gendered lives of former cult members. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 31(3), 323–360. doi: 10.1177/0891241602031003003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosc, M. (2000). Assessment of social functioning in depression. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 41(1), 63–69. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(00)90133-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosc, M., Dubini, A., & Polin, V. (1997). Development and validation of a social functioning scale, the social adaptation self-evaluation scale. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 7(1), 57–70. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(97)00420-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell‐Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC): Validation of a 10‐item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates, D. D. (2010). Post-involvement difficulties experienced by former members of charismatic groups. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(3), 296–310. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9251-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates, D. D. (2016). Life inside a deviant “religious” group: Conformity and commitment as ensured through “brainwashing” or as the result of normal processes of socialization. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 44, 103–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlcj.2015.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coker, A. L., Watkins, K. W., Smith, P. H., & Brandt, H. M. (2003). Social support reduces the impact of partner violence on health: Application of structural equation models. Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00122-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw, S., Hammerton, G., Mahedy, L., Sellers, R., Owen, M. J., Craddock, N., … Thapar, A. (2016). Mental health resilience in the adolescent offspring of parents with depression: A prospective longitudinal study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(1), 49–57. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00358-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor‐Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durocher, N. (1999). Insights from cult survivors regarding group support. British Journal of Social Work, 29(4), 581–599. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/29.4.581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasde, I., & Block, R. A. (1998). Cult experience: Psychological abuse, distress, personality characteristics, and changes in personal relationships reported by former members of Church Universal and Triumphant. Cultic Studies Journal, 15, 192–221. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, K., Morgan, M., Wooley, C., & Powis, T. (2011). Life after centrepoint: Accounts of adult adjustment after childhood spent at an experimental community. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, L., Goldberg, W., Henry, R., & Langone, M. (Eds.) (2017). Cult recovery: A clinician’s guide to working with former members and families. Bonita Springs. [Google Scholar]

- Göransson, M., & Holmqvist, R. (2018). Is psychological distress among former cult members related to psychological abuse in the cult? International Journal of Cultic Studies, 9, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S. A., & Shah, M. J. (2019). The anatomy of undue influence used by terrorist cults and traffickers to induce helplessness and trauma, so creating false identities. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 8, 97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2019.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, K. H., Thurston, I. B., Schwartz, L. E., Jamison, L. E., & Hasselle, A. J. (2018). Protective factors associated with resilience in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence, 8(4), 438. doi: 10.1037/vio0000147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, L. (2016). Born and raised in a sect: You are not alone. Progression Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lalich, J. A., & Tobias, M. (2006). Take back your life: Recovery from cults and abusive relationships. Berkeley, CA: Bay Tree Press. [Google Scholar]

- Machisa, M. T., Christofides, N., & Jewkes, R. (2018). Social support factors associated with psychological resilience among women survivors of intimate partner violence in Gauteng, South Africa. Global Health Action, 11(sup3), 1491114. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1491114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinoski, P. T., Langone, M. D., & Lynn, S. J. (1999). Psychological distress in former members of the International Churches of Christ and noncultic groups. Cultic Studies Journal, 16, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, C. H., & Salazar, C. F. (2014). Second-generation adult former cult group members’ recovery experiences: Implications for counseling. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 36(2), 188–203. doi: 10.1007/s10447-013-9201-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, K., Goldberg, L., Langone, M., & DeVoe, K. (2007). A workshop for people born or raised in cultic groups. ICSA E-Newsletter, 6. http://www.icsahome.com/articles/sgaworkshop

- McCaw, B., Golding, J. M., Farley, M., & Minkoff, J. R. (2007). Domestic violence and abuse, health status, and social functioning. Women & Health, 45(2), 1–23. doi: 10.1300/J013v45n02_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Carballeira, A., Saldaña, O., Almendros, C., Martín-Peña, J., Escartín, J., & Porrúa-García, C. (2015). Group psychological abuse: Taxonomy and severity of its components. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 7, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselet, M., Duretete, O., Hardouin, J. B., & Grall-Bronnec, M. (2017). Cult membership: What factors contribute to joining or leaving? Psychiatry Research, 257, 27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, O., Antelo, E., Almendros, C., & Rodríguez-Carballeira, A. (2019). Development and validation of a measure of emotional distress in survivors of group psychological abuse. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 22, Article E33. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2019.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, O., Antelo, E., & Rodríguez-Carballeira, A. (2020). Nuevas evidencias de validez de la Escala de Abuso Psicológico Experimentado en Grupos [New evidence of validity of the Psychological Abuse Experienced in Groups Scale]. XII Congreso Internacional de Psicología Jurídica y Forense, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, O., Antelo, E., Rodríguez-Carballeira, A., & Almendros, C. (2018). Taxonomy of psychological and social disturbances in survivors of group psychological abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(9), 1003–1021. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1405315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, O., Rodríguez-Carballeira, Á., Almendros, C., & Escartín, J. (2017). Development and validation of the psychological abuse experienced in groups scale. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 9(2), 57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpal.2017.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, O., Rodríguez-Carballeira, Á., Almendros, C., & Guilera, G. (2021). Group psychological abuse and psychopathological symptoms: The mediating role of psychological stress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(11–12), NP6602–NP6623. doi: 10.1177/0886260518815710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm, J. A., Briggs-Phillips, M., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2006). Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19(6), 825–836. doi: 10.1002/jts.20159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, A. M., Molton, I. R., Alschuler, K. N., Ehde, D. M., & Jensen, M. P. (2015). Resilience predicts functional outcomes in people aging with disability: A longitudinal investigation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(7), 1262–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel, L. M., Pietrzak, R. H., Charney, D. S., Mayes, L. C., & Southwick, S. M. (2015). How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecology and Society, 20(4). doi: 10.5751/ES-07832-200410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Pietrzak, R. H., & Southwick, S. M. (2012). The role of coping, resilience, and social support in mediating the relation between PTSD and social functioning in veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 75(2), 135–149. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.2.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo, A. P., Briscione, M., Norrholm, S. D., Jovanovic, T., McCullough, S. A., Skelton, K., & Bradley, B. (2017). Psychological resilience is associated with more intact social functioning in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Psychiatry Research, 249, 206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due that it contains information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.