Abstract

Households experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) and food insecurity are at high risk of lifelong physical and behavioral difficulties. Longitudinal data from a perinatal home-visiting cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial in South Africa townships were used to examine the relationships between household settings and mothers’ histories of risk and children’s behavior problems at 3 and 5 years of age. IPV, food insecurity, maternal depressed mood, and geriatric pregnancy (at age of 35 or older) were consistently associated with children’s internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems. Aggressive behavior was more prevalent among 3- and 5-year olds boys, and was associated with maternal alcohol use. The effects of these factors on child behavior were more prominent than maternal HIV status. There is a continuing need to reduce IPV and household food insecurity, as well as supporting older, depressed, alcohol using mothers in order to address children’s behavioral needs.

Keywords: Child behavior problems, Maternal risks, Intimate Partner Violence, Food insecurity, HIV, Longitudinal studies

Introduction

Rates of violence in South Africa are among the highest in the world [1]. About 62% of women have been violently assaulted [2], with about half of maternal murders resulting from their partners. In the townships of Cape Town, one in four women of childbearing age report intimate partner violence (IPV) [3–6]. Witnessing violence in the home has a negative effect on children’s early development [7] and can have lifelong implications for children’s emotional and mental health [8–10]. IPV has been consistently linked to later adjustment problems and a recent review of longitudinal studies suggests that when younger children are exposed to IPV, the association between IPV and child externalizing and internalizing problems is greater [11]. These studies are predominately from high-income countries (HICs). There are fewer data on children growing up in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where 90% of children and adolescents live [12]. The current study examines the association of exposure to IPV and early adjustment in a cohort of children growing up in the townships of Cape Town in South Africa.

Examining early behavior, specifically, is important in understanding how early life exposures impact adjustment and developmental trajectories. Specifically, exhibiting early externalizing behaviors is associated with lower educational achievement, deficits in executive functioning [13, 14], higher risks for substance use [15], and violence [16] later in life. Internalizing behaviors, on the other hand, are linked to increased risks of depression and suicide [17]. More recent studies have also found associations between early externalizing and internalizing behaviors and their contribution anxiety and depression later in life, suggesting a more complex relationship between early childhood behaviors and their consequences as an adult [18].

IPV is only one of the stressors for South African children, as households face persistent adversity from many sources. These include lack of basic services like sanitation, running water, sufficient food [19], and housing where most dwellings are informal shacks rather than secure structures [20]. Food insecurity, in particular, has been linked to children’s emotional and behavioral development as well as physical health [21–23]. In the current cohort, food insecurity is common, with almost half of mothers reporting being hungry in the past week [24]. Furthermore, the majority of parents do not cohabitate, so mothers are often raising their children independently [24]. These structural stressors have been consistently linked to mental-health problems, not only in adults [25] but also in young children [7].

Women in Cape Town townships also face concurrent health challenges including high rates of depressive symptoms (30%), alcohol use (25%), and HIV (26%) [3–6]. Rates of depression among mothers living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa are high (43.5% antenatal and 31.1% postpartum) and these comorbid challenges contribute to the burdens experienced by young mothers in caring for themselves and their children [26, 27]. Among mothers living with HIV, depressive symptoms have been linked to poorer adherence to antiretroviral therapy and exclusive breastfeeding, both of which can increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission [28, 29]. Alcohol use further complicates child-rearing in this context with 20-30% of South African mothers reporting alcohol use and mothers living with HIV, particularity those with depressed symptoms, being at increased risk for alcohol abuse [30, 31]. In HICs, there is consistent evidence of the negative consequences of maternal depression on children’s well-being [32, 33]. Recently, these examinations have included cohorts in LMICs [34–37]; however, much less is understood about the impact of maternal mental health among mothers raising children in environments characterized by widespread poverty and food insecurity than in HICs.

The longitudinal data analyzed here were collected over the course of a 5-year cluster-randomized controlled trial conducted in 24 neighborhoods among townships of Cape Town, South Africa. The focus of the study was to determine whether a community-based perinatal home-visiting intervention program could improve maternal and child health. While there were significant early effects of the home-visiting intervention [24], evaluations of 3-year and 5-year child outcomes have not revealed significant intervention effects, and analyses of maternal outcomes have yielded only limited indications of intervention efficacy. Given the lack of long-term effectiveness, the analyses in the current study do not focus on any intervention effects. Beyond evaluations of the home-visiting intervention, available data provide a foundation to examine connections among household risks (IPV, food insecurity), maternal risk factors (depression, alcohol use, HIV), and children’s behavioral adjustment over the first years of life. Consistent with previous studies, we hypothesized that maternal health risks, along with deficits in household support would negatively impact early childhood behavioral outcomes as manifested in both internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

Methods

The Institutional Review Boards of University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and Stellenbosch University approved the study (IRB#10-000386; ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00996528; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00972699). Three independent teams conducted the assessments (Stellenbosch), intervention (Philani Nutrition Project), and randomization and data analyses (UCLA).

Study design and participants

As previously published [20], 24 neighborhoods (typically 450-600 households) among Cape Town townships were identified and matched for size, housing-units density, number of alcohol bars, distance to local health centers, and length of residence, and migration. Data were collected over the course of a cluster-randomized controlled trial, in which neighborhoods were randomized either to: (1) receiving a paraprofessional home-visit intervention (n = 12 neighborhoods, n = 644 mothers); or (2) receiving the standard-care (n = 12 neighborhoods, n = 594 mothers).

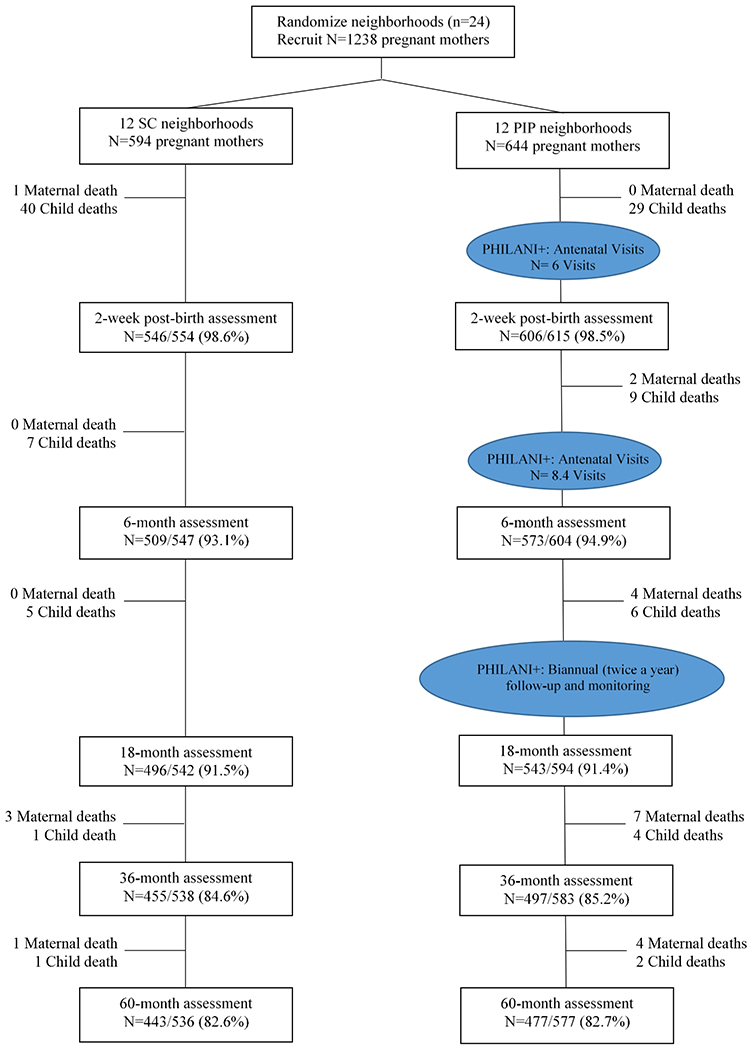

Almost all pregnant mothers (98%) were identified over 15-month period by township peers functioning as recruiters. Households (mothers and children) were assessed during pregnancy, within 2 weeks of birth, and at 0.5, 1.5, 3, and 5 years post-birth, with follow-up rates of 98.6%, 94%, 92%, 85%, and 83% as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Philani participant flow diagram

Intervention conditions

The standard care condition included access to antenatal clinics within 5 kilometers, hospitals for child delivery, primary care clinics for postnatal and well-baby care, dedicated postnatal clinics for HIV+ women and babies, and separate sites for HIV testing of male partners. Standard Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) services were provided across all clinics, including HIV testing, maternal and child anti-retroviral (ARV) treatment, nevirapine during child birth, and Cipro and PCR testing for infants at 6 weeks. By 2012, access to ARV, pre- and postnatally, was provided to mothers living with HIV and their children.

The perinatal home-visiting condition was conducted by paraprofessional community health workers (CHW). Each CHW was assigned 40 pregnant women on their caseload, and they conducted four antenatal and four postnatal home visits during the first four months post-birth, and then checked in about once a month to deliver support as needed, including daily visits if a family was in a crisis. CHWs encouraged pregnant mothers to attend at least four antenatal healthcare visits; to take prenatal vitamins and folic acid provided by clinics; recognize warning signs for a problematic pregnancy; exclusively breastfeed children and delay solid foods for babies for a minimum of six months; and to abstain from alcohol and smoking during pregnancy. The antenatal and post-birth visits typically lasted about 31 minutes and covered the following specific topics: HIV; alcohol use; nutrition; child assistance grant and other resources; self-care and social support.

Measures

All measures were administered at a research office by data collectors routinely supervised, who had initially been recruited from the townships, at each of the six scheduled assessments.

Child behavioral outcomes

At 3 years, mothers completed the Pre-school Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL/1½–5) [38], a 99-item questionnaire reporting the presence or absence of behavioral problems in children within the past 2 months. The CBCL Total Problems score at 3 years was calculated by summing all of the responses on a 0-2 Likert scale, where 0 referred to “Not true”, 1 referred to “Somewhat or sometimes true”, and 2 referred to “Very or often true”. Lower scores represent better child behavioral health. The CBCL Internalizing Behavior Problems score was computed by summing item scores of emotional reactivity (9 items), anxious/depressed syndrome profiles (8 items), somatic complaints (11 items), and evidence of being withdrawn (8 items), and the Externalizing Behavior Problems score was calculated by summing the item scores of attention problems (5 items) and aggression syndrome (19 items). Children were considered having behaviour problems if they exhibited a Total Problems scale score ≥ 52.2 (1 SD above the mean), or a score ≥ 21 on the Externalizing Problems composite scale, or a score ≥ 14 on the Internalizing Problems composite scale. At 5 years, mothers completed the CBCL questionnaire on Aggressive Behavior subscale (19 items). Children who scored ≥ 16.9 on the Aggressive Behavior subscale were seen as exhibiting aggressive behavior [38].

Maternal measurements

Intimate partner violence –

Mothers reported at each assessment whether they had been slapped, pushed or shoved, and/or threatened with a weapon by a current partner in the past 12 months.

Food insecurity –

A single-item measure from The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) was administered at each assessment, where mothers self-reported the number of days in the past week that they (mother/child) gone hungry. This measure has been found to be highly correlated with the 9-item scale used to distinguish food insecure from food secure households across different cultural contexts [39]. Food insecurity was defined if mothers ever reported being hungry in the last seven days.

Depressive symptoms –

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [40, 41], a 10-item questionnaire identifies symptoms of depression (within the past seven days) was administered at each assessment. A cut-off score greater than 13 was used to indicate probable depressed mood.

Alcohol use –

Mothers reported any alcohol use at each assessment. At baseline, mothers were asked to report on alcohol use prior to discovery of pregnancy; within 2 weeks of birth, alcohol use in the month prior to birth was reported; at 6 months post-birth, alcohol use since the baby was born was reported; and at the remaining assessments, alcohol use in the month prior to the assessment was reported.

HIV status –

At each assessment, mothers self-reported their HIV status, which had also been recorded on the child’s clinic Road-to-Health card (RtHC), a government-issued record completed by health clinic staff.

Maternal and structural characteristics –

Demographic and key structural factors included maternal age at the baseline assessment (i.e. 18 – 24, 25 – 34, and 35 years or older); partnership status (i.e. being single vs. married or living with a partner); type of housing (i.e. informal shack vs. formal housing); and having monthly household income under 2000 ZAR (about $135 USD).

Data Analysis

Demographic and maternal characteristics at baseline were compared between the home-visiting intervention and the standard-care condition using chi-squared (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests for discrete variables, and Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables.

Longitudinal mixed-effects models were used to examine household risks, maternal risks, and sociodemographic factors associated with child behavioral outcomes at 3 and 5 years post-birth. In particular, viewing outcomes as continuous scores, linear mixed-effects models were used to analyze Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Problems scores at 3 years and the Aggressive Behavior subscale score at 3 and 5 years. In addition, mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to examine binary behavioral outcomes. The mixed models included fixed effects for IPV, food insecurity, depressive symptoms, alcohol use, maternal HIV status, intervention, maternal age, marital status, household income, informal housing, and child gender. The mixed model for the Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Problems included a random intercept accounting for neighborhood random effects. The longitudinal model for the Aggressive Behavior subscale score, which was assessed at two time points, was modeled using repeated measures within neighborhoods, including random intercepts for subjects, and fixed effect for time.

We focus on an at-risk portion of the available sample; the analyses here include households, where both mother and child survived throughout the study period (104 children and 22 mothers died). Not included were 17 HIV+ children and 13 households in which mother had either a twin (24 children) or triplet (3 children).

Although the amount of missing data on individual measures at any given time-point was limited, we utilized a multiple imputation strategy to mitigate potential bias due to incomplete data [42]. Out of 12 key variables used in each of the analysis models, eight had fewer than 7% missing values, while the outcome variable, Aggressive Behavior subscale score, had around 20% missing at 5 years. Nighty-three percent of individuals had complete data at 3 years on all variables used in the initial analysis models for the Internalizing and Externalizing, and Total Problems scores, and 75% percent of the individuals had complete data jointly at 3 and 5 years on all variables in the analysis model for the Aggressive Behavior score. Missing values were assumed to be missing at random, where the probability of a value being missing allowed to depend on observed values but does not depend on the underlying unobserved value after conditioning on observed values.

Multiple imputation via fully-conditional specification [43, 44] was adopted to address missing data in binary and continuous variables, incorporating random intercepts to preserve the complexity of the multilevel data structure [45]. Missing values in each behavioral outcomes were imputed at the composite/scale levels. The imputation models incorporated 12 variables used in the analysis models, as well as two auxiliary variables: maternal education level and child pre-school attendance (“1” = not attend vs. “0” = attend), which seemed to be predictive of missing values or non-response.

All variables, except the completely observed variables (i.e. intervention, maternal age, education level, housing type, and child gender) were imputed, ensuring that each partially observed covariate is imputed from an imputation model compatible with the associated analysis model. Multiple imputation was carried out separately in the intervention and the standard-care groups using 20 imputed datasets in each. The two sets of imputed data were combined prior to analysis. All estimates of the model parameters were obtained by averaging results across the 20 imputed datasets with inferences under Multiple imputation using Rubin’s rules [42]. All analyses were conducted using Stata SE software version 16 [46] and the stand-alone imputation program Blimp Version 1.1 [47].

The results obtained from the mixed-effects models, that implicitly account for incomplete longitudinal outcomes, were comparable to the findings from multiple imputation indicating that the inferences based on the mixed-effects models were not highly sensitive to underlying assumptions regarding missing data (see Tables S1 and S2).

Results

Demographic characteristics of participants were similar across intervention arms (Table 1). Average age in pregnancy was 26.4 years (SD = 5.5); half were between 18-24 years old and about 10% were 35 years and older. Mothers had completed an average of 10.3 years (SD = 1.8) of schooling, more than 80% were unemployed, and only half were married or living with a partner. Almost half had monthly household income under 2000 ZAR; approximately two-thirds lived in an informal house/shack, and more than half experienced food insecurity in the last week. More than a third experienced IPV, one-third reported probable depressed mood (EPDS > 13), and approximately one-third were mothers living with HIV. Roughly 25% drank alcohol in the month prior to pregnancy discovery; 10% reported drinking alcohol after pregnancy discovery [24, 48].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample at baseline by intervention arms

| Intervention (N=644) | Standard-care (N=594) | Total (N=1,238) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Demographic | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Age, median [Range] | 25.0 [18.0 - 42.0] | 25.0 [18.0 - 42.0] | 25.0 [18.0 - 42.0] | |||

| Age category | ||||||

| 18-24 | 264 | 41.0 | 274 | 46.1 | 538 | 43.5 |

| 25-34 | 319 | 49.5 | 265 | 44.6 | 584 | 47.2 |

| 35 and older | 61 | 9.5 | 55 | 9.3 | 116 | 9.4 |

| Highest education level, median [Range] | 11.0 [0.0 −14.0] | 11.0 [0.0 −14.0] | 11.0 [0.0 −14.0] | |||

| Currently unemployed | 515 | 80.0 | 490 | 82.5 | 1005 | 81.2 |

| Not married or lived with partner | 267 | 41.5 | 270 | 45.5 | 537 | 43.4 |

| Monthly income ≤ 2000 ZAR | 334 | 54.4 | 301 | 51.9 | 635 | 53.2 |

| Informal housing | 447 | 69.4 | 403 | 67.8 | 850 | 68.7 |

| Food insecurity | 333 | 51.7 | 331 | 55.7 | 664 | 53.6 |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| Drank any alcohol, month prior to pregnancy discovery | 155 | 24.1 | 129 | 25.8 | 284 | 24.8 |

| Drank any alcohol, after pregnancy discovery | 56 | 8.7 | 49 | 9.8 | 105 | 9.2 |

| Mental health | ||||||

| EPDS > 13 | 238 | 37.0 | 195 | 32.8 | 433 | 35.0 |

| HIV and reproductive health behavior | ||||||

| Intimate partner violence | 205 | 35.3 | 201 | 38.6 | 406 | 36.9 |

| Mothers living with HIV | 188 | 31.5 | 175 | 31.6 | 363 | 31.5 |

The mean Total Problems score at 3 years was 47.9 (SD = 22.9) with almost one-third of the children scoring in the at risk range. The mean Internalizing Problems score was 13.4 (SD = 8.0) with 43.5% of the children scoring in the at risk range, and the mean Externalizing Problems score was 17.5 (SD = 8.6) with about one-third (32.7%) of the children scoring in the at risk range. One-quarter of the children met criteria as being in the problematic aggressive range at 3 and 5 years, separately, where the mean level for the Aggressive Behavior score was 12.7 (SD = 7.2) at 3 years and 10.7 (SD = 8.1) at 5 years.

Household and maternal risks associated with child behavioral outcomes

In the following sections, we report the estimated mean differences (MDs) – Table 2 – and the estimated odds ratios (ORs) – Table 3 – along with their associated standard errors (SE) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the multiple imputation approach.

Table 2.

Estimated regression coefficient with 95% CI obtained from multiple imputation for analysis of child behavioral outcomes on potential structural factors and maternal risks

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year assessment | 3- & 5-year assessments | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Internalizing Composite Score† | Externalizing Composite Score† | Total Scale Score† | Aggressive Behavior Subscale Score†† | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Estimate | SE | 95% CI | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Child gender, Male | 0.7 | 0.5 | (−0.3, 1.7) | 1.9 *** | 0.6 | (0.8, 3.0) | 4.2 *** | 1.5 | (1.4, 7.1) | 1.9 *** | 0.4 | (1.1, 2.7) |

| Not Married or lives with partner | −0.4 | 0.6 | (−1.5, 0.7) | −0.2 | 0.6 | (−1.4, 1.1) | −1.3 | 1.6 | (−4.5, 1.9) | −0.1 | 0.4 | (−0.9, 0.7) |

| Monthly income ≤ 2000 ZAR | −0.7 | 0.6 | (−1.9, 0.5) | −0.5 * | 0.6 | (−1.8, 0.8) | −1.1 | 1.7 | (−4.4, 2.2) | 0.0 | 0.4 | (−0.8, 0.9) |

| Informal housing | 0.4 | 0.6 | (−0.8, 1.6) | 0.5 | 0.7 | (−0.8, 1.8) | 1.6 | 1.7 | (−1.8, 4.9) | 0.8 | 0.5 | (−0.2, −1.7) |

| Food insecurity | 2.0 ** | 0.8 | (0.4, 3.5) | 2.2 *** | 0.6 | (1.0, 3.4) | 7.9 *** | 1.6 | (4.8, 11.0) | 1.7 *** | 0.4 | (0.9, 2.5) |

| Maternal age | ||||||||||||

| 25-34 years | 0.0 | 0.6 | (−1.1, 1.1) | 0.3 | 0.6 | (−0.9, 1.6) | 0.5 | 1.7 | (−2.7, 3.8) | 0.1 | 0.5 | (−0.8, 1.1) |

| 35 years and above | 2.7 *** | 0.9 | (0.8, 4.5) | 2.3 ** | 1.0 | (0.3, 4.4) | 7.2 *** | 2.7 | (2.0, 12.5) | 2.2 *** | 0.8 | (0.8, 3.7) |

| Maternal depressed mood (EPDS >13) | 3.0 *** | 0.7 | (1.7, 4.4) | 2.3 *** | 0.8 | (0.8, 3.8) | 8.9 *** | 2.0 | (5.0, 12.8) | 1.6 ** | 0.5 | (0.6, 2.5) |

| Alcohol use | 0.7 | 0.7 | (−0.7, 2.1) | 1.6 * | 0.8 | (0.0, 3.2) | 3.7 * | 2.1 | (−0.4, 7.8) | 1.5 *** | 0.5 | (0.5, 2.5) |

| Intimate partner violence | 2.3 *** | 0.5 | (1.2, 3.4) | 2.3 *** | 0.8 | (0.6, 4.0) | 7.6 *** | 2.2 | (3.2, 11.9) | 1.6 *** | 0.5 | (0.5, 2.6) |

| Mother living with HIV | −0.6 | 0.6 | (−1.7, 0.6) | 0.6 | 0.6 | (−0.7, 1.8) | −0.1 | 1.7 | (−3.3, 3.2) | 0.2 | 0.5 | (−0.7, 1.1) |

| Intervention | 0.8 | 0.6 | (−0.5, 2.0) | 0.3 | 0.7 | (−1.0. 1.7) | 1.5 | 1.8 | (−2.0, 4.9) | 0.1 | 0.5 | (−0.9, 1.2) |

| Time | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −1.6 *** | 0.3 | (−2.2, −1.0) |

Note:

p<0.1 (Italic font);

p<.05 (Bold font);

p<.01 (Bold font).

Analysis model was a linear mixed-effects model, accounting for repeated-subject measures within neighborhoods using random intercepts for neighborhoods.

Analysis model was a linear mixed-effects model, accounting for repeated-subject measures within neighborhoods using random intercepts for neighborhoods and for subjects.

Table 3.

Estimated regression coefficient with 95% CI obtained from multiple imputation for analysis of child behavioral outcomes on potential structural factors and maternal risks

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year assessment | 3- & 5-year assessments | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Internalizing Composite Score†† | Externalizing Composite Score†† | Total Scale Score†† | Aggressive Behavior Subscale Score† | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Symptomatic ≥14 | Symptomatic ≥21 | Symptomatic ≥52.2 | Symptomatic ≥16.9 | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| OR | SE | 95% CI | OR | SE | 95% CI | OR | SE | 95% CI | OR | SE | 95% CI | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Child gender, Male | 1.1 | 0.1 | (0.9, 1.5) | 1.4 ** | 0.1 | (1.1, 1.9) | 1.4 ** | 0.2 | (1.0, 1.9) | 1.9 *** | 0.3 | (1.4, 2.7) |

| Not Married or lives with partner | 0.7 * | 0.1 | (0.5, 1.0) | 0.9 | 0.2 | (0.6, 1.2) | 0.8 | 0.1 | (0.6, 1.2) | 0.9 | 0.2 | (0.6, 1.3) |

| Monthly income ≤ 2000 ZAR | 0.8 | 0.1 | (0.6, 1.1) | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.4) | 0.9 | 0.2 | (0.6, 1.2) | 1.1 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.6) |

| Informal housing | 0.9 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.3) | 1.1 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.5) | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.4) | 1.2 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.7) |

| Food insecurity | 1.6 *** | 0.2 | (1.2, 2.2) | 1.7 *** | 0.2 | (1.3, 2.3) | 1.9 *** | 0.2 | (1.4, 2.6) | 2.1 *** | 0.4 | (1.5, 2.9) |

| Maternal age | ||||||||||||

| 25-34 years | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.4) | 1.1 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.5) | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.4) | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.5) |

| 35 years and above | 1.4 | 0.3 | (0.9, 2.4) | 1.3 | 0.3 | (0.8, 2.2) | 1.7 * | 0.3 | (1.0, 2.8) | 2.2 *** | 0.7 | (1.3, 4.0) |

| Maternal depressed mood (EPDS >13) | 2.1 *** | 0.4 | (1.5, 3.1) | 1.7 *** | 0.2 | (1.2, 2.4) | 2.3 *** | 0.2 | (1.6, 3.4) | 1.4 * | 0.3 | (1.0, 2.2) |

| Alcohol use | 1.4 | 0.3 | (0.9, 2.1) | 1.2 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.8) | 1.3 | 0.2 | (0.9, 2.0) | 1.5 * | 0.3 | (1.0, 2.3) |

| Intimate partner violence | 2.0 *** | 0.4 | (1.3, 3.0) | 1.2 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.8) | 1.6 ** | 0.2 | (1.1, 2.4) | 1.5 * | 0.3 | (1.0, 2.4) |

| Mother living with HIV | 0.8 | 0.1 | (0.6, 1.1) | 1.1 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.5) | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.4) | 1.2 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.7) |

| Intervention | 1.3 | 0.2 | (0.9, 1.9) | 1.2 | 0.2 | (0.9, 1.6) | 1.0 | 0.2 | (0.7, 1.4) | 1.1 | 0.2 | (0.8, 1.5) |

| Time | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.9 | 0.1 | (0.6, 1.2) |

Note:

p<0.1 (Italic font);

p<.05 (Bold font);

p<.01 (Bold font).

Analysis model was a logistic mixed-effects model, accounting for repeated-subject measures within neighborhoods using random intercepts for neighborhoods.

Analysis model was a logistic mixed-effects model, accounting for repeated-subject measures within neighborhoods using random intercepts for neighborhoods and for subjects.

Three-Year Assessment

IPV –

Experiencing IPV was associated with higher levels of Internalizing (MD: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.2, 3.4), Externalizing (MD: 2.3; 95% CI: 0.6, 4.0), and Total Problems (MD: 7.6; 95% CI: 3.2, 11.9). Furthermore, the odds of being at risk on the Internalizing (OR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.3, 3.0) and Total Problems (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.4) scales were higher among children of mothers who experienced IPV.

Food insecurity –

Experiencing food insecurity in the past week was associated with higher scores on the Internalizing (MD: 2.0; 95% CI: 0.4, 3.5), Externalizing (MD: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.0, 3.4), and Total Problems (MD: 7.9; 95% CI: 4.8, 11.0) scales. Additionally, the odds of being at risk on the Internalizing (OR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.2, 2.2), Externalizing (OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3, 2.3), and Total Problems (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.4, 2.6) scales were higher among mothers and children who experienced food insecurity.

Depressed mood –

Having mothers with depressed mood was associated with higher levels for Internalizing (MD: 3.0; 95% CI: 1.7, 4.4), Externalizing (MD: 2.3; 95% CI: 0.8, 3.8), and Total Problems (MD: 8.9; 95% CI: 5.0, 12.8). In addition, the odds of exhibiting Internalizing (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.5, 3.1), Externalizing (OR: 1.7; 95% CI: 1.2, 2.4), and Total Problems (OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.6, 3.4) in the at risk range were higher among mothers who reported depressed mood.

Alcohol use –

No evidence of significant association was observed between drinking alcohol and children’s behavior problems.

Maternal age –

Being pregnant at 35 years or older was associated with higher scores for Internalizing (MD: 2.7; 95% CI: 0.8, 4.5), Externalizing (MD: 2.3; 95% CI: 0.3, 4.4), and Total Problems (MD: 7.2; 95% CI: 2.0, 12.5).

Child gender –

Male children appeared to have higher Externalizing (MD: 1.9; 95% CI: 0.8, 3.0) and Total Problem scores (MD: 4.2; 95% CI: 1.4, 7.1) than female children. Similarly, the odds of exhibiting Externalizing (OR: 1.4; 95% CI: 1.1, 1.9) and Total Problems (OR: 1.4; 95% CI: 1.0, 1.9) in the at risk range were higher among male than female children.

Three-Year and Five-Year Assessments

Experiencing IPV (MD: 1.6; 95% CI: 0.5, 2.6) and food insecurity (MD: 1.7; 95% CI: 0.9, 2.5), as well as having a depressed mood (MD: 1.6; 95% CI: 0.6, 2.5), drinking alcohol (MD: 1.5; 95% CI: 0.5, 2.5), and pregnancy at age of 35 or older (MD: 2.2; 95% CI: 0.8, 3.7) were associated with higher levels of children’s aggression problems. Male children scored higher on Aggressive Behavior subscale (MD: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.1, 2.7) than females. Similarly, experiencing food insecurity (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 1.5, 2.9) and pregnancy at 35 years or older (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.4, 2.6) increased the odds of exhibiting aggressive behavior in the problematic range. Aggression was more prevalent among male children (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.4, 2.7) than female children.

Overall, the mean-level changes in Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Problems and Aggressive Behavior were comparable in terms of partnership status, having income under 2000 ZAR, living in informal housing or being HIV+. Similarly, no evidence of consistent association was observed between these factors and exhibiting behavioral problems.

Discussion

In this study, we found that having a history of IPV, experiencing food insecurity, maternal depressed mood, and being over the age of 35 at the child’s birth were consistently associated with children’s behavior problems. Alcohol use showed less consistent associations with children’s behaviors. We also found evidence of elevated risk of worse child behaviors among male children. The effects of these household factors and maternal risks on child behavior were more prominent than maternal HIV status.

About one in three children in the current study show early behavioral and emotional problems by the age of 3 years in the townships of Cape Town. This rate is 50% higher than those found among children and adolescents in HICs including the United States (21%), Canada (18%), and Germany (21%) [49, 50].

Consistent with previous research, children exhibiting Internalizing behaviors experience more health issues [17]. Internalizing behavior is elevated when mothers experienced IPV. It is not surprising that the child’s externalizing and internalizing behavior will further challenge the mother’s coping ability. In addition, witnessing violence early in life has been consistently associated with an increased risk of later depression [51, 52], a consideration that especially important given recent widespread concern about the consequences of IPV in South Africa [53, 54]. Rather than IPV alone impacting children’s adjustment, IPV typically co-occurs in a cluster of symptoms – IPV, maternal depression, and alcohol use. We have documented in the current context that they are highly likely to co-occur [6], and we have collected the information on IPV at multiple time-points. However, whether there is a sequencing of how these risks emerge within a household, this is not determinable in our data.

Beyond IPV, there is ongoing interest in understanding differences in the development of emotional and behavioral problems between boys and girls. Some studies associate adversity with internalizing problems in girls and externalizing problems in boys [55, 56]. Evidence that the relationship between exposure to domestic violence and aggression and externalizing behavior is stronger for boys than for girls [51, 57] raises the question of whether later violence against women is part of a developmental cascade of externalizing behavior. Similar chain-reaction hypotheses contemplate linkages among IPV, maternal alcohol use, maternal depression, and consequent difficulties in the next generation of children, carrying the potential to fuel a continuation of the cycle [10].

Limitations

Interpretation of our findings is subject to a number of assumptions and limitations. We are not aware of studies examining reliability and validity of the CBCL/1½–5 assessment in South Africa, raising a question about whether reliability and validity findings from the United States or elsewhere [58] would be applicable to the societal context in South Africa. In our study, at the 5-year assessment, mothers were only asked about CBCL Aggression Behavior questions, limiting our ability to examine internalizing symptoms during early childhood.

We evaluated maternal self-reports of HIV by checking the child’s RtHC and the mother’s health record, and we performed 602 rapid tests for HIV and found high correlations between maternal self-reports and rapid-test results. Nevertheless, the finding that HIV status did not predict maladaptive child behaviors would have been strengthened by more routine HIV testing by study personnel.

The behavioral outcome-measures studied here were based on responses to several questionnaire items; we also considered the possibility of imputation at item-level. Such an approach makes the task of imputation more technically challenging, which was reflected in convergence problems in associated statistical computing approaches. However, given that the missing data patterns observed in the present study primarily involved unit non-response, it stands to reason that multiple imputation at the composite/scale-level could deal with missing data in the behavioral outcomes without substantial loss of generality [59].

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings provide evidence from an at-risk population in Cape Town townships, South Africa, showing the importance of both maternal risks and structural stressors in early childhood behaviors. Future investigations in LMICs would be valuable to gain further insight into how maternal and child vulnerabilities influence child behavioral problems through adolescence as well as into predictors of healthy adjustment.

Summary

Intimate partner violence, food insecurity, maternal depressed mood, and geriatric pregnancy (at age of 35 or older) were the vulnerabilities most consistently associated with worse behavioral outcomes of children living in the townships of Cape Town. Maternal alcohol use showed less consistent association with child behavior. The potential long-term adverse effects of early exposures underscore the relevance of considering how best to provide services to improve mothers’ safety and well-being, and how best to support children who have been exposed to risk factors for psychological harm.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Estimated regression coefficient with 95% CI obtained from linear mixed-effects model for analysis of child behavioral outcomes on potential structural factors and maternal risks

Table S2. Estimated regression coefficient with 95% CI obtained from logistic mixed-effects model for analysis of child behavioral outcomes on potential structural factors and maternal risks

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) R01AA017104 and supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) MH58107, 5P30AI028697, and UL1TR000124. PHR is supported by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) T32MH109205 and Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services (CHIPTS) P30MH58107. MT is supported by the National Research Foundation (South Africa) and is a lead investigator of the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University of the Witwatersrand, in South Africa. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations:

- ARV

Anti-retroviral

- CBCL

Child Behavior Checklist

- CHWs

Community health workers

- CI

Confidence interval

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- HFIAS

Household Food Insecurity Access Scale

- HICs

high-income countries

- IPV

Intimate partner violence

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- MD

Mean difference

- OR

Odds ratio

- PMTCT

Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission

- RtHC

Road-to-Health card

- SD

Standard deviation

- SE

Standard error

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval The Institutional Review Boards of University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) and Stellenbosch University approved the study (IRB#10-000386). All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent All mothers provided written, voluntary, informed consent.

References

- 1.NationMaster (2010) Murder rate per million people: Countries Compared. https://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Crime/Violent-crime/Murder-rate-per-million-people, (accessed).

- 2.Gordon C (2016) Intimate partner violence is everyone’s problem, but how should we approach it in a clinical setting? S Afr J Med Sci 106: 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honikman S, van Heyningen T, Field S, Baron E, Tomlinson M (2012) Stepped Care for Maternal Mental Health: A Case Study of the Perinatal Mental Health Project in South Africa. PLoS Med. 9: e1001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotheram-Fuller EJ, Tomlinson M, Scheffler A, Weichle TW, Rezvan PH, Comulada WS et al. (2018) Maternal Patterns of Antenatal and Postnatal Depressed Mood and the Impact on Child Health at 3-Years Postpartum. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 86: 218–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, Le Roux I, Stein JA (2015) Alcohol Use, Partner Violence, and Depression A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Among Urban South African Mothers Over 3 Years. Am. J. Prev. Med 49: 715–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis EC, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Weichle TW, Rezai R, Tomlinson M (2017) Patterns of Alcohol Abuse, Depression, and Intimate Partner Violence Among Township Mothers in South Africa Over 5 Years. AIDS Behav. 21: 174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund IO, Skurtveit S, Handal M, Bukten A, Torvik FA, Ystrom E et al. (2019) Association of Constellations of Parental Risk With Children’s Subsequent Anxiety and Depression Findings From a HUNT Survey and Health Registry Study. JAMA Pediatr 173: 251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Comm Early Childhood Adoption D, Sect Dev Behav P, Comm Psychosocial Aspects Child F, Committee on Early Childhood A et al. (2012) The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress. Pediatr. 129: E232–E246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, McCarry TW, Nurse M, Gilhooly T et al. (2010) Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Dev Sci 13: 46–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt X, Tomlinson M (2018) Child Developmental Trajectories in Adversity: Environmental Embedding and Developmental Cascades in Contexts of Risk. In Understanding Uniqueness and Diversity in Child and Adolescent Mental Health (Hodes M. et al. eds), pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vu NL, Jouriles EN, McDonald R, Rosenfield D (2016) Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal associations with child adjustment problems. Clin. Psychol. Rev 46: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieling CMD, Baker-Henningham HP, Belfer MP, Conti GP, Ertem IMD, Omigbodun OP et al. (2011) Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 378: 1515–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, Tiemeier H (2016) The bidirectional pathways between internalizing and externalizing problems and academic performance from 6 to 18 years. Dev. Psychopathol 28: 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woltering S, Lishak V, Hodgson N, Granic I, Zelazo PD (2016) Executive function in children with externalizing and comorbid internalizing behavior problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 57: 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtmann M, Buchmann AF, Esser G, Schmidt MH, Banaschewski T,Laucht M (2011) The Child Behavior Checklist-Dysregulation Profile predicts substance use, suicidality, and functional impairment: a longitudinal analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimball E (2016) Edleson Revisited: Reviewing Children’s Witnessing of Domestic Violence 15 Years Later. J. Fam. Violence 31: 625–637. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klomek ABPD Sourander AMD, Niemelä SMD Kumpulainen KMD, Piha JMD Tamminen TMD et al. (2009) Childhood Bullying Behaviors as a Risk for Suicide Attempts and Completed Suicides: A Population-Based Birth Cohort Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 48: 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fanti KA, Hellfeldt K, Colins OF, Meehan A, Andershed A-K, Andershed H et al. (2019) Worried, sad, and breaking rules? Understanding the developmental interrelations among symptoms of anxiety, depression, and conduct problems during early childhood. J Crim Justice 62: 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barros AJDD Ronsmans CP, Axelson HM Loaiza EP, Bertoldi ADP França GVAM et al. (2012) Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 379: 1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Mbewu N, Comulada WS, le Roux K et al. (2011) Philani Plus (+): A Mentor Mother Community Health Worker Home Visiting Program to Improve Maternal and Infants’ Outcomes. Prev. Sci 12: 372–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA,Jones SJ (2005) Food insecurity affects school children’s academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J. Nutr 135: 2831–2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitaker RC, Phillips SM,Orzol SM (2006) Food Insecurity and the Risks of Depression and Anxiety in Mothers and Behavior Problems in their Preschool-Aged Children. Pediatr. 118: e859–E868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seligman HK, Laraia BA,Kushel MB (2010) Food Insecurity Is Associated with Chronic Disease among Low-Income NHANES Participants. J. Nutr 140: 304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, le Roux IM, Harwood JM, Comulada S, O’Connor MJ et al. (2014) A Cluster Randomised Controlled Effectiveness Trial Evaluating Perinatal Home Visiting among South African Mothers/Infants. PLoS One 9: e105934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baingana F, Bannon I,Thomas R (2005) Mental health and conflicts: Conceptual framework and approaches. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garber J (2005) Depression and the Family. In Psychopathology and the Family (Hudson JL. and Rapee RM. eds), pp. 225–280. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowa NA, Cholera R, Pence BW,Gaynes BN (2015) Perinatal Depression in HIV-Infected African Women: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76: 1385–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Anderson J, Peltzer K, Wampold S, Cotton MF et al. (2012) Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 26: 2039–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuthill EL, Pellowski JA, Young SL,Butler LM (2017) Perinatal Depression Among HIV-Infected Women in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa: Prenatal Depression Predicts Lower Rates of Exclusive Breastfeeding. AIDS Behav. 21: 1691–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vythilingum Roos, Faure SC Geerts,Stein DJ (2012) Risk factors for substance use in pregnant women in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J 102: 853–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desmond K, Milburn N, Richter L, Tomlinson M, Greco E, van Heerden A et al. (2011) Alcohol consumption among HIV-positive pregnant women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Prevalence and correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 120: 113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brand SR,Brennan PA (2009) Impact of Antenatal and Postpartum Maternal Mental Illness: How are the Children? Clin. Obstet. Gynecol 52: 441–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Cullen C, Schanberg S,Kuhn C (2004) Prepartum, Postpartum, and Chronic Depression Effects on Newborns. Psychiatry 67: 63–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein AP, Pearson RMP, Goodman SHP, Rapa ED, Rahman AP, McCallum MMA et al. (2014) Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 384: 1800–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher J, de Mello MC, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S et al. (2012) Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ 90: 139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies LA, Cockcroft K, Olinger L, Chersich M, Urban M, Makkan CMC et al. (2017) Alcohol exposure during pregnancy altered childhood developmental trajectories in a rural South African community. Acta Paediatr. 106: 1802–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Subramoney S, Eastman E, Adnams C, Stein DJ,Donald KA (2018) The Early Developmental Outcomes of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure: A Review. Front. Neurol 9: 1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Achenbach TM,Rescorla LA. (2000) Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS,Rotheram-Borus MJ (2016) Food insufficiency, depression, and the modifying role of social support: Evidence from a population-based, prospective cohort of pregnant women in peri-urban South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med 151: 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cox JL, Holden JM,Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of Postnatal Depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 150: 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rochat T, Tomlinson M, Newell M,Stein A (2013) Detection of antenatal depression in rural HIV-affected populations with short and ultrashort versions of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Arch Womens Ment Health 16: 401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin DB. (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys, 1st edn., Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Buuren S, Brand JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn C,Rubin DB (2006) Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation. J Stat Comput Simul 76: 1049–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartlett JW, Seaman SR, White IR,Carpenter JR (2014) Multiple imputation of covariates by fully conditional specification: Accommodating the substantive model. Stat. Methods Med. Res 24: 462–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Enders CK, Keller BT,Levy R (2018) A fully conditional specification approach to multilevel imputation of categorical and continuous variables. Psychol. Methods 23: 298–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.StataCorp., Stata Statistical Software: Release 16, College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keller BT,Enders CK, Blimp User’s Manual (Version 1.1), Los Angeles, CA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomlinson M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Youssef M, Nelson SH, Scheffler A et al. (2016) Thirty-Six-Month Outcomes of a Generalist Paraprofessional Perinatal Home Visiting Intervention in South Africa on Maternal Health and Child Health and Development. Prev. Sci 17: 937–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization: WHO (2005) Atlas: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Resources: Global Concerns, Implications for the Future. https://www.who.int/mental_health/resources/Child_ado_atlas.pdf, (accessed).

- 50.Cree RA, Bitsko RH, Robinson LR, Holbrook JR, Danielson ML, Smith C et al. (2018) Health Care, Family, and Community Factors Associated with Mental, Behavioral, and Developmental Disorders and Poverty Among Children Aged 2-8 Years - United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 67: 1377–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Widom CS,Wilson HW (2015) Intergenerational Transmission of Violence. In Violence and Mental Health, pp. 27–45, Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skeen S, Macedo A, Tomlinson M, Hensels IS,Sherr L (2016) Exposure to violence and psychological well-being over time in children affected by HIV/AIDS in South Africa and Malawi. AIDS Care 28: 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russell M, Cupp PK, Jewkes RK, Gevers A, Mathews C, LeFleur-Bellerose C et al. (2014) Intimate Partner Violence Among Adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. Prev. Sci 15: 283–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campbell J (2019) What’s Behind South Africa’s Recent Violence? https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/whats-behind-south-africas-recent-violence, (accessed 2020).

- 55.Lewis T, McElroy E, Harlaar N,Runyan D (2015) Does the impact of child sexual abuse differ from maltreated but non-sexually abused children? A prospective examination of the impact of child sexual abuse on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Child Abuse Neglect 51: 31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thurman TR, Kidman R, Nice J,Ikamari L (2015) Family Functioning and Child Behavioral Problems in Households Affected by HIV and AIDS in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 19: 1408–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR,Kenny ED (2003) Child Witnesses to Domestic Violence: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 71: 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rescorla L, Achenbach T, Ivanova MY, Dumenci L, Almqvist F, Bilenberg N et al. (2007) Behavioral and emotional problems reported by parents of children ages 6 to 16 in 31 societies. J Emot Behav Disord 15: 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rombach I, Gray AM, Jenkinson C, Murray DW,Rivero-Arias O (2018) Multiple imputation for patient reported outcome measures in randomised controlled trials: advantages and disadnantages of imputing at the item, subscale or composite score level. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 18: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Estimated regression coefficient with 95% CI obtained from linear mixed-effects model for analysis of child behavioral outcomes on potential structural factors and maternal risks

Table S2. Estimated regression coefficient with 95% CI obtained from logistic mixed-effects model for analysis of child behavioral outcomes on potential structural factors and maternal risks