Abstract

Purpose

To investigate PD-L1 protein expression and gene amplification in lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC) and analyse their correlation with the clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of LUSC patients.

Patients and Methods

Tissue samples from 164 LUSC patients were collected. PD-L1 protein was detected by immunochemistry (IHC), and PD-L1 gene amplification was investigated by fluorescence in situ hybridization in LUSC patients.

Results

The positive expression rate of PD-L1 in LUSC was 47.6% (78/164), and the amplification rate of PD-L1 was 6.7% (11/164); both rates were higher than those of paratumor tissue. Both PD-L1 positive expression and gene amplification were correlated with clinical stage and lymph node metastasis (P<0.05). PD-L1 protein expression, PD-L1 gene amplification, late stage, lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis were significantly correlated with the prognosis of patients. Among these factors, late stage, lymph node metastasis, PD-L1 protein expression and PD-L1 gene amplification were independent prognostic factors for LUSC.

Conclusion

Positive PD-L1 protein expression and gene amplification are involved in the malignant progression and metastasis of LUSC. Both PD-L1 protein expression and gene amplification are associated with poor prognosis.

Keywords: PD-L1 protein expression, PD-L1 gene amplification, lung squamous cell carcinoma, prognosis

Introduction

Lung cancer is a malignant tumor with the highest morbidity and mortality worldwide.1 Histological types of lung cancer include non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). NSCLC is a malignant tumor with high rates of recurrence and metastasis.2,3 NSCLC has several histological subtypes, including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), and large cell carcinoma. LUSC and adenocarcinoma account for the majority of NSCLC. Various oncogene mutations mainly occur in lung adenocarcinoma,4 and driver oncogene mutations, such as EGFR and KRAS mutations, can be found in more than three-quarters of Chinese lung adenocarcinoma patients. Therefore, a variety of gene-targeting drugs for lung adenocarcinoma, such as erlotinib, have been widely used in clinical practice. However, driver gene mutation incidence in LUSC is low, and molecular targeted therapy in LUSC patients is ineffective.5–7 Fortunately, PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors have been observed to play increasingly important roles in LUSC. At present, screening patients who benefit from PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors mainly depends on PD-L1 protein expression detection by IHC. However, due to the use of different reagent manufacturers and platforms, detection criteria have not been standardised until recently. Therefore, it is urgent to find new biomarkers to provide more evidence for precisely screening beneficiaries.

Lee KS found that in CRC patients, PD-L1 gene amplification definitely contributes to the upregulation of the PD 1/PD-L1 axis.8 However, only a few studies with small samples have reported detectable PD-L1 amplification in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, cervical squamous cell carcinoma and triple-negative breast cancer. Generally, according to genetic central dogma, gene amplification leads to high expression of the protein, but it is not necessarily the only cause, because the protein overexpression may be caused by complex molecular mechanism. Therefore, it is one of the purposes of the study to analyse whether PD-L1 protein overexpression and PD-L1 gene amplification are consistent. If they are consistent, the two methods, that is, the protein expression detected by IHC and gene amplification detected by FISH, can be mutually verified in clinical practice.

Currently, the prognosis significance of PD-L1 gene amplification has been rarely studied and the findings of PD-L1 protein expression in malignant tumours remain controversial.9–16Therefore, we analysed the prognosis significance of PD-L1 protein overexpression and PD-L1 gene amplification in LUSC to determine whether the biomarker is a predictor of the clinical prognosis in LUSC patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Samples

A total of 164 LUSC patients in Shanxi Tumor Hospital between December 2012 and December 2013 were enrolled. All patients underwent radical surgical treatment for lung cancer. Patients with radiation and chemotherapy were excluded. Complete clinicopathologic and follow-up data of the patients were collected. Clinical stage was determined according to the ninth edition of the TNM staging system (Union for International Cancer Control, UICC). Among 164 patients, 146 were male and 18 were female. All patients were followed-up, and the deadline for follow-up was March 2020. All collected specimens were handled and made anonymous according to accepted ethical and legal standards. This study was approved by the Institute Research Medical Ethics Committee of Shanxi Tumor Hospital and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed written informed consent.

Construction of Tissue Microarrays (TMAs)

Three TMAs were constructed containing 164 LUSC and 16 normal control tissue cores. First, each H&E-stained section was reviewed retrospectively. Two pathologists selected representative formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks. Then, a hollow needle was used to punch and extract cores (0.9-mm diameter) from each tumor sample. Two cores were extracted from typical cancer cell nest zones in each sample for TMAs construction, and the protein expression rates of the two cores were averaged. Next, the cores were embedded in paraffin blocks of more than 10 lines across 6 rows for a total of three tissue chips with 180 samples.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

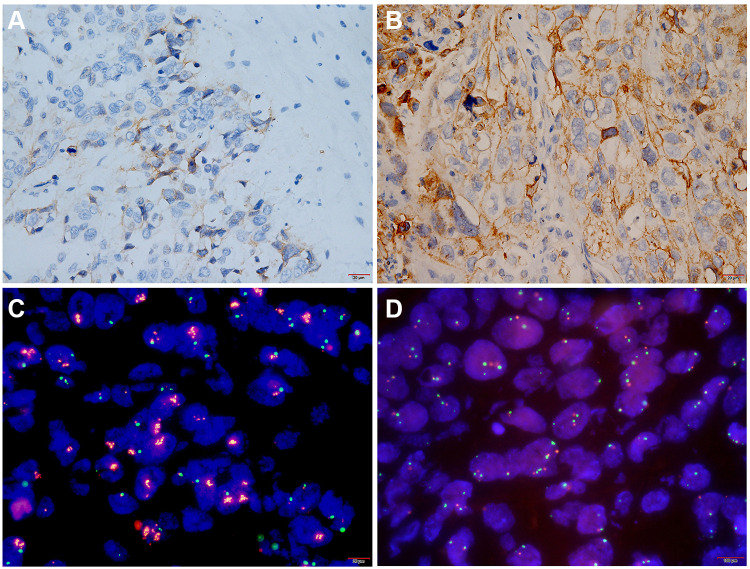

PD-L1 protein expression was detected by immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry was conducted using a Dako PD-L1 IHC 22C3 Pharm DX Assay Kit (Agilent Technologies Co. Ltd., USA) on the Dako Autostainer Link 48 (ASL48) platform. The operation was performed according to manufacturer recommendations. Briefly, the tissue sections underwent deparaffinization, rehydration and antigen retrieval. Following FLEX peroxidase blocking for 5 minutes, specimens were incubated with 22C3 clone anti-PD-L1 antibody (mouse, 1:50, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for 60 minutes at room temperature. Specimens were then incubated with the EnVision™ FLEX+ Mouse LINKER and the EnVision™ FLEX HRP visualization reagent for 30 minutes at room temperature. Finally, the specimens were developed with DAB and counterstained with haematoxylin and covered with a cover-slip. Each IHC run contained a positive control (on-slide tonsil tissue) and a negative antibody control (buffer, no primary antibody). PD-L1 expression was determined using TPS, and staining of the tumor cell membrane or basal membrane and lateral membrane with brown-yellow particles was regarded as positive expression. Cytoplasmic staining was considered nonspecific and was excluded in the assessment of staining intensity. Normal cells and tumor-associated immune cells, such as infiltrating lymphocytes or macrophages, were not included in the scoring for determining PD-L1 expression level. Using TPS≥1% and TPS≥50% as cut-offs, the expression of PD-L1 was classified into three levels (Table 1): PD-L1 TPS<1% (negative); PD-L1 1%≤TPS≤49% (Figure 1A); PD-L1 TPS≥50% (Figure 1B). Two experienced pathologists each independently read the sections.

Table 1.

Classification of PD-L1 Protein Expression Level in LUSC

| PD-L1 Expression Status | PD-L1 Expression Levels | Staining Type |

|---|---|---|

| No PD-L1 Expression | TPS<1% | Tumor cells showing partial or complete cell membrane staining (≥ 1 +) accounted for less than 1% of viable tumor cells. |

| PD-L1 Expression (Low to medium) | 1%≤TPS≤49% | Tumor cells with partial or complete cell membrane staining (≥ 1 +) accounted for 1–49% of viable tumor cells. |

| High PD-L1 Expression | TPS≥50% | Tumor cells with partial or complete cell membrane staining (≥ 1 +) accounted for more than 50% of viable tumor cells. |

Figure 1.

PD-L1 protein expression and gene amplification in lung squamous cell carcinoma. (A and B) Representative images of PD-L1 protein expression. (A) Low to moderate expression of PD-L1 (1%≤TPS≤49%) × 400. (B) High expression of PD-L1 protein (TPS> 50%) × 400. (C and D) Representative images of PD-L1 gene amplification analysed by FISH. (C) PD-L1 gene amplified Ratio > 2, parts of PD-L1 gene (red fluorescence) were expressed in clusters ×1000. (D) PD-L1 gene without amplification×1000.

Fluorescence in situ Hybridization (FISH)

A PD-L1 (9p24) two-color probe was used (Guangzhou Ambiping Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., China) to perform FISH. The sections were placed in an oven at 65°C for 30 minutes and successively immersed in xylene, 100% ethanol and distilled water 2–3 times. Afterwards, proteolysis was performed with a pepsin working liquid at 37°C for 10 minutes. Then, each section was immersed in 2×SSC for 5 minutes, dehydrated in gradient ethanol for 2 minutes, and dried naturally. Probe liquid was poured on the tissue area and covered with a cover glass. The slices were placed in a hybridization instrument (Abbott Laboratories, USA). DNA was denatured at 85°C for 5 minutes and hybridized at 37°C for 10–16 hours. Finally, cells were counterstained with DAPI, and the number of double-color signals indicative of tumor cells was counted in at least 30 cells in a high-power field. Red signals signified the PD-L1 gene, and green signals were indicative of the chromosome 9 centromere. PD-L1 gene amplification was defined as follows: (1) ratio value ≥2.0; ratio value was average gene/average centromere (or average value of the red signal/average value of the green signal ≥2.0)(Figure 1C); (2) ratio value <2.0, but average copy number of PD-L1 ≥6.0 (or average red signal number ≥6.0 or many red signals were connected in clusters)(Figure 1D). No PD-L1 gene amplification was indicated if the ratio value was less than 2.0 and the average red signal number was less than 4.0.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 26.0 statistical software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyse the data. The relationship of PD-L1 protein expression and PD-L1 gene amplification with clinicopathological factors was analysed by the χ2 test. Correlation between PD-L1 protein expression and PD-L1 gene amplification was analysed by Spearman correlation analysis. Overall survival (OS) was defined from the date of surgery to the last follow-up or death. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined from the date of surgery to recurrence. Univariate analysis of prognostic factors was done by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Log rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed by Cox regression analysis. P<0.05 was considered significant for all the above analyses.

Results

PD-L1 Protein Expression and Gene Amplification in LUSC

PD-L1 was negatively expressed in all paratumor tissues and weakly expressed in inflammatory cells. PD-L1 protein was mainly observed on cancer cell membranes (Figure 1); the results are shown in Table 2. The positive rate of PD-L1 was 47.6% (78/164). Among the 164 LUSC patients, 86 cases (52.4%) had negative expression (TPS < 1%), 47 cases (28.7%) had moderate expression (1% ≤ TPS ≤ 49%), and 31 cases (18.9%) had high expression of PD-L1 (TPS ≥ 50%). The amplification rate of PD-L1 in LUSC was 6.7% (11/164). Among these 11 patients (Table 3), the positive expression rate of PD-L1 protein was 100% (11/11), including 7 patients with high expression (7/11, 63.6%) and 4 patients with moderate expression of PD-L1 (4/11, 36.4%). Correlation analysis showed that PD-L1 gene amplification was positively correlated with protein expression intensity (r=0.786, P<0.001, Table 3), which revealed that PD-L1 protein expression and PD-L1 gene amplification were consistent in LUSC.

Table 2.

Relationship Between PD-L1 Gene Amplification and Clinicopathological Features of Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma

| Variable | Total | PD-L1 Amplification | PD-L1 Expression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | χ2 | p-value | <1% | 1–49% | ≥50% | χ2 | p-value | ||

| Total | 164 | 153 | 11 | 86 | 47 | 31 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 18 | 15 | 3 | 3.495 | 0.073 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 3.283 | 0.194 |

| Male | 146 | 138 | 8 | 80 | 39 | 27 | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤60 | 87 | 79 | 8 | 6.462 | 0.176 | 37 | 30 | 20 | 7.300 | 0.026 |

| >60 | 77 | 74 | 3 | 49 | 17 | 11 | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Yes | 101 | 94 | 7 | 0.728 | 0.885 | 60 | 26 | 15 | 5.496 | 0.064 |

| No | 63 | 59 | 4 | 26 | 21 | 16 | ||||

| Tumor size | ||||||||||

| T1 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 9.847 | 0.340 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20.450 | <0.001 |

| T2 | 75 | 72 | 3 | 28 | 33 | 14 | ||||

| T3 | 85 | 77 | 8 | 57 | 12 | 16 | ||||

| Histological grade | ||||||||||

| 1 | 44 | 40 | 4 | 1.802 | 0.531 | 26 | 10 | 8 | 1.347 | 0.853 |

| 2 | 49 | 45 | 4 | 24 | 15 | 10 | ||||

| 3 | 71 | 68 | 3 | 36 | 22 | 13 | ||||

| Stage | ||||||||||

| I | 39 | 39 | 0 | 52.897 | <0.001 | 27 | 9 | 3 | 15.391 | 0.017 |

| II | 84 | 81 | 3 | 45 | 23 | 16 | ||||

| III | 37 | 32 | 5 | 13 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| IV | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||||

| Yes | 71 | 61 | 10 | 49.639 | 0.001 | 14 | 34 | 23 | 53.774 | <0.001 |

| No | 93 | 92 | 1 | 72 | 13 | 8 | ||||

| Metastasis | ||||||||||

| Yes | 4 | 1 | 3 | 30.973 | <0.001 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4.436 | 0.109 |

| No | 160 | 152 | 8 | 85 | 44 | 31 | ||||

| Relapse | ||||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 7 | 0 | 1.501 | 0.468 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0.725 | 0.696 |

| No | 157 | 146 | 11 | 83 | 44 | 30 | ||||

Table 3.

Correlation Between PD-L1 Gene Amplification and Protein Expression

| PD-L1 Amplification | PD-L1 Expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1% | 1–49% | ≥50% | r=0.786 | P<0.001 | |

| Yes | 0 | 4 | 7 | ||

| No | 86 | 44 | 23 | ||

Relationship Between PD-L1 Protein Expression, Gene Amplification and Clinicopathological Characteristics of Patients with LUSC (See Table 2)

Positive PD-L1 protein expression was significantly correlated with age, tumor size, clinical stage and lymph node metastasis in LUSC patients (P<0.05) but not correlated with gender, smoking, histological grade, distant metastasis and recurrence (P>0.05). PD-L1 gene amplification was significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis in LUSC patients (P<0.05) but was not related to gender, age, smoking, histological grade, tumor size, or recurrence (P>0.05). The PD-L1 protein positive expression rate in patients under 60 years old was significantly higher than that in patients over 60 years old (P=0.026). Gene amplification and protein expression rates of patients with advanced stage cancer (P<0.001) were significantly higher than those of patients in early stage cancer (P=0.017), and in those with lymph node metastasis, they were significantly higher than in those without lymph node metastasis (P=0.001; P<0.001). The amplification rate of PD-L1 gene in patients with distant metastasis was significantly higher than that in patients without distant metastasis (P<0.001).

PD-L1 Positive Expression and Gene Amplification Predict Poor Prognosis in LUSC Patients

Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 2) showed that the DFS and OS of patients with moderate and high PD-L1 expression were significantly shorter than those of patients with negative PD-L1 expression. The median survival (64.29±1.99) of patients with low PD-L1 expression was significantly longer than those with moderate (52.89±2.847) and high PD-L1 expression (36.359±2.297) (P<0.001, see Table 4). Compared with patients without PD-L1 amplification, the DFS and OS of patients with PD-L1 amplification were significantly shorter, and the median survival (27.909±3.942) was significantly shorter than that of patients without PD-L1 amplification (58.184±1.636) (P<0.001, see Table 4). Patients with PD-L1 expression >50% and gene amplification positive had shorter survival time than those patients with PD-L1 expression >50% and negative gene amplification (P<0.001, see Table 4). Even in patients with PD-L1 protein expression below 50%, that accompanied by positive gene amplification had significantly shorter survival time than patients with negative gene amplification (P<0.001, see Table 4). Multivariate analysis showed that clinical stage, lymph node metastasis, PD-L1 protein expression and PD-L1 gene amplification were independent adverse prognostic factors for LUSC (see Table 5).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of PD-L1 amplification and expression in patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. (A and C) DFS curve of patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. (B and D) OS curve of patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma. (E) DFS curve of PD-L1 expression >50% and gene amplification. (F) OS curve of PD-L1 expression >50% and gene amplification. (G) DFS curve of PD-L1 expression<50% and gene amplification. (H) OS curve of PD-L1 expression <50% and gene amplification.

Table 4.

Univariate Prognostic Factor Analysis by Log Rank Test

| Variable | Total | Disease-Free Survival | Overall Survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE (Months) | 95% CI | P | Mean ± SE (Months) | 95% CI | P | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 18 | 38.726±4.682 | 29.550–47.903 | 0.458 | 52.434±5.124 | 42.391–62.478 | 0.358 |

| Male | 146 | 42.153± 1.641 | 38.936–45.370 | 56.618±1.757 | 53.173–60.062 | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≤60 | 87 | 38.142± 2.114 | 33.999–42.284 | 0.046 | 51.473± 2.026 | 47.149–55.707 | 0.006 |

| >60 | 77 | 45.851±2.168 | 41.601–50.101 | 61.394± 2.351 | 56.787–66.001 | ||

| Smoking | |||||||

| Yes | 101 | 43.377±2.018 | 39.422–47.333 | 0.221 | 57.998±2.181 | 48.347–58.373 | 0.153 |

| No | 63 | 39.372±2.406 | 34.656–44.089 | 53.360±2.558 | 53.723±62.273 | ||

| Tumor status | |||||||

| T1 | 4 | 46.500±10.618 | 25.688–67.312 | 0.155 | 60.250±9.630 | 41.376–79.124 | 0.169 |

| T2 | 75 | 45.797±2.127 | 41.627–49.967 | 60.478±2.302 | 55.967–64.989 | ||

| T3 | 85 | 38.053±2.216 | 33.709–42.379 | 52.235±2.388 | 47.555–56.915 | ||

| Histological grade | |||||||

| 1 | 44 | 42.243±3.224 | 35.924–48.562 | 0.689 | 57.26±03.602 | 50.200–64.319 | 0.555 |

| 2 | 49 | 40.361±2.653 | 35.161–45.561 | 54.681±2.814 | 49.165–60.198 | ||

| 3 | 71 | 42.350±2.311 | 37.820–46.880 | 56.449±2.461 | 51.626–61.272 | ||

| Stage | |||||||

| I | 39 | 49.736±2.760 | 44.327–55.145 | <0.001 | 66.524±2.816 | 61.004–72.043 | <0.001 |

| II | 84 | 43.933±1.976 | 40.059–47.807 | 57.701±2.037 | 53.708–61.695 | ||

| III | 37 | 30.872±3.271 | 24.461–37.283 | 44.554±3.819 | 37.068–52.039 | ||

| IV | 4 | 14.500±3.610 | 7.425–21.575 | 26.000±6.364 | 13.527–38.473 | ||

| Lymph node | |||||||

| Yes | 71 | 36.594±2.414 | 31.863–41.325 | 0.026 | 49.510±2.635 | 44.344–54.675 | 0.015 |

| No | 93 | 45.531±1.853 | 41.898–49.163 | 60.844±1.920 | 57.081–64.606 | ||

| Metastasis | |||||||

| Yes | 4 | 14.500±3.610 | 7.425–21.575 | <0.001 | 26.000±6.364 | 13.527–38.473 | <0.001 |

| No | 160 | 42.309±1.540 | 39.291–45.327 | 56.753±1.646 | 53.527–59.979 | ||

| Relapse | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 42.143±8.221 | 26.029–58.257 | 0.901 | 55.000±8.608 | 38.129–71.871 | 0.926 |

| No | 157 | 41.771±1.579 | 38.677–44.865 | 56.199±1.696 | 52.875–59.522 | ||

| PD-L1 expression | |||||||

| <1% | 86 | 49.281±1.801 | 45.751–52.811 | <0.001 | 64.291±1.992 | 60.388–68.195 | <0.001 |

| 1–49% | 47 | 38.652±2.801 | 33.161–44.143 | 52.892±2.847 | 47.311–58.473 | ||

| ≥50% | 31 | 23.925±2.221 | 19.572–44.143 | 36.359±2.297 | 31.858–40.860 | ||

| PD-L1 amplification | |||||||

| No | 153 | 43.934±1.507 | 40.980–46.889 | <0.001 | 58.184±1.636 | 54.978–61.391 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 11 | 11.909±1.522 | 8.925–14.893 | 27.909±3.942 | 20.184–35.634 | ||

| PD-L1 >50% | |||||||

| And gene amplification (+) | 8 | 11.625±1.658 | 8.376–14.874 | <0.001 | 29.875±4.812 | 20.443–39.307 | 0.130 |

| And gene amplification (-) | 22 | 28.461±2.454 | 23.650–33.271 | 38.885±2.608 | 33.774–43.996 | ||

| PD-L1 <50% | |||||||

| And gene amplification (+) | 3 | 12.667±4.055 | 4.719–20.615 | <0.001 | 22.667±7.055 | 57.756–64.380 | <0.001 |

| And gene amplification (-) | 131 | 46.269–1.591 | 43.149–49.388 | 61.068±1.690 | 59.275–66.725 | ||

Table 5.

Cox Multivariate Survival Analysis in LSUC Patents

| Variable | Disease-Free Survival | Overall Survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (years) | 0.823 | 0.576–1.175 | 0.283 | 0.823 | 0.576–1.175 | 0.179 |

| Stage | 0.001 | 0.184 | ||||

| Stage (1) | 0.219 | 0.043–1.101 | 0.065 | 0.315 | 0.063–1.577 | 0.160 |

| Stage (2) | 0.306 | 0.066–1.418 | 0.130 | 0.416 | 0.093–1.853 | 0.250 |

| Stage (3) | 0.838 | 0.180–3.897 | 0.822 | 0.691 | 0.157–3.042 | 0.625 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 2.696 | 1.521–4.779 | 0.001 | 0.494 | 0.284–0.861 | 0.013 |

| PD-L1 expression | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| PD-L1 expression (1) | 0.168 | 0.088–0.320 | <0.001 | 0.050 | 0.010–0.249 | <0.001 |

| PD-L1 expression (2) | 0.415 | 0.231–0.746 | 0.003 | 0.228 | 0.048–1.077 | 0.062 |

| PD-L1 amplification | 0.102 | 0.038–0.268 | <0.001 | 2.552 | 1.547–4.210 | <0.001 |

Discussion

Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1, also known as B7-H1, CD274) is a transmembrane protein that belongs to the B7 family.17 Human PD-L1 gene is located on chromosome 9p24.1. Programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) is mainly expressed on T lymphocytes.18 High PD-L1 expression is found in a variety of solid tumors, such as lung cancer, liver cancer, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer. PD-L1 on tumor cells binds PD-1 receptors on T cells, resulting in the dephosphorylation of Sh2p-driven T cell receptors and its coreceptor CD28, which inhibits T cell activation,19 weakening the ability of T cells to kill tumor cells. Under this mechanism, tumor cells can evade immune surveillance and promote tumor migration.20,21 The results of this study showed that there were 47.6% patients with PD-L1 positive expression in LUSC, and the expression of PD-L1 was related to lymph node metastasis and advanced stage. The results indicated that high PD-L1 expression was involved in progression and metastasis of lung squamous cell carcinoma.

The significance of PD-L1 expression in the prognosis of lung cancer remains controversial.

A few studies have shown that PD-L1 expression was associated with better prognosis or longer overall survival;22–26 only Ameratunga et al have suggested that the expression of PD-L1 was not associated with prognosis;27 most studies have suggested that the expression of PD-L1 in lung cancer cells was associated with poor prognoses,11,28–35 which is consistent with the results of this study. Both univariate analysis and multivariate analysis showed PD-L1 protein expression was significantly correlated with poor prognosis and was an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in clinical practice.

Generally, gene amplification leads to high expression of the protein, but it is not necessarily the only cause, because the protein overexpression may be caused by complex molecular mechanism, such as gene enhancer mutation, modification and regulation of transcription and translation levels, and protein stability etc. Hence, gene amplification and protein overexpression are not always consistent in malignant tumors. However, there were few researches into PD-L1 gene amplification and its consistency with protein expression in lung cancer. Inoue Yusuke et al evaluated the PD-L1 copy number of 194 cases of NSCLC and found that the PD-L1 amplification rate was only 2.6%,15 Some studies in European, American and Japanese populations have shown that PD-L1 gene amplification in NSCLC patients the PD-L1 gene amplification rate was lower than 5.3%.10,36,37 In this study, we found that the amplification rate of the PD-L1 gene in squamous cell carcinoma was 6.7%, which was slightly higher than the average amplification rate of all types of previously studied NSCLCs. Moreover, patients with PD-L1 gene amplification showed positive expression of PD-L1 protein, which supported that PD-L1 gene amplification contributes to PD-L1 protein expression in LUSC. Therefore, PD-L1 protein expression detected by IHC and PD-L1 gene amplification detected by FISH can be mutually verified in clinical practice.

As we all know, there are controversies surrounding the prognostic significance of PD-L1 gene amplification, and the prognostic implication of PD-L1 gene amplification has been rarely studied. Inoue Yusuke found that the DFS and OS of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 amplification showed good survival results.15 Other studies have shown that PD-L1 gene amplification in NSCLC patients was associated with poor prognosis,36,37 which corresponds with our findings. The results demonstrate that both PD-L1 protein expression and gene amplification can be poor prognosis predictors for LUSC patients.

As it is a retrospective investigation, this study has certain limitations. First of all, all the LUSC patients from this cohort underwent surgical therapy without being treated with PD-L1 inhibitor. So, we will expand the sample size to include patients who have undergone PD-L1 inhibitor therapy in the subsequent research so as to analyse the relationship between biomarkers and the efficacy of PD-L1 inhibitors. In addition, this study only observed the phenomenon that PD-L1 expression increased in patients in advanced clinical stages with high rates of LNs and distant metastasis, which suggested the accompanying relationship between PD-L1 and tumor progression. Further research needs to do be done to clarify whether high PD-L1 expression is a cause or a result or an accompanied feature of highly aggressive tumors.

Conclusion

PD-L1 protein overexpression and gene amplification are consistent in LUSC. PD-L1 protein and gene amplification related to the malignant progression and metastasis of lung squamous cell carcinoma and both can predict poor prognosis. Therefore, in addition to PD-L1 protein, PD-L1 gene amplification may be used as a new routine detection marker for the immunotherapy of lung squamous cell carcinoma.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants of the followings:Shanxi Province foundation of supporting scientific research projects of returned overseas students (Grant number: 2020-156);Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (Grant number: 201801D121347);Natural Science Foundation of LVliang Science Bureau (Grant number: 2020SHFZ28 and 2020SHFZ32).We are grateful to Bu fan and Jingjing JI for their generous help in providing experimental methods. We also thank Yingying Zhao and Zijuan Zeng for data analyses.

Abbreviations

LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; IHC, immunochemistry; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; TMAs, Construction of tissue microarrays; ASL48, Autostainer Link 48; FISH, Fluorescence in situ hybridization; DFS, Disease-free survival; OS, Overall survival; PD-1, Programmed death receptor-1; PD-L1, Programmed cell death ligand 1; HR, hazard ratio.

Author Contributions

Zhenwen Chen, Ning Zhao and Yirong Xu designed the whole study, collected the tissue specimens and performed FISH methods, read the sections and taken the picture of FISH, collected and analyzed data, then wrote the draft paper and revised paper. Yanfeng Xi, Huiwen Wu, Xiaoai Tian and Qi Wang developed the idea for the clinical study, collected clinicopathological data, performed IHC and wrote the materials of draft paper and revised the paper. All authors have reviewed and approved the drafted and final paper. All authors have agreed on the journal to which the article will be submitted and agreed to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Ma Q, Yao R, Liu J. Current status and development of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy for lung cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;79:106088. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z, Fillmore CM, Hammerman PS, Kim CF, Wong KK. Non-small-cell lung cancers: a heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(8):535–546. doi: 10.1038/nrc3775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandara DR, Hammerman PS, Sos ML, Lara PN Jr., Hirsch FR. Squamous cell lung cancer: from tumor genomics to cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(10):2236–2243. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-14-3039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer CJ, Redman MW, Wade JL 3rd, et al. SWOG S1400B (NCT02785913), a Phase II Study of GDC-0032 (Taselisib) for previously treated PI3K-positive patients with stage IV squamous cell lung cancer (lung-MAP sub-study). J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(10):1839–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goss GD, Felip E, Cobo M, et al. Association of ERBB mutations with clinical outcomes of afatinib- or erlotinib-treated patients with lung squamous cell carcinoma: secondary analysis of the LUX-lung 8 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):1189–1197. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma G, Deng Y, Jiang H, Li W, Wu Q, Zhou Q. The prognostic role of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer patients: an updated meta-analysis. Clini Chim Acta. 2018;482:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KS, Kim BH, Oh HK, et al. Programmed cell death ligand-1 protein expression and CD274/PD-L1 gene amplification in colorectal cancer: implications for prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(9):2957–2969. doi: 10.1111/cas.13716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takada K, Okamoto T, Toyokawa G, et al. The expression of PD-L1 protein as a prognostic factor in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2017;104:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun JM, Zhou W, Choi YL, et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a large cohort study of surgically resected cases. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(7):1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceeraz S, Nowak EC, Noelle RJ. B7 family checkpoint regulators in immune regulation and disease. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(11):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roemer MG, Advani RH, Ligon AH, et al. PD-L1 and PD-L2 genetic alterations define classical hodgkin lymphoma and predict outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(23):2690–2697. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma LJ, Feng FL, Dong LQ, et al. Clinical significance of PD-1/PD-Ls gene amplification and overexpression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Theranostics. 2018;8(20):5690–5702. doi: 10.7150/thno.28742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Wang JF, Li XW, Bu P, Bai W, Li LM. Relationship between PD-L1 protein expression and gene amplification in gastric cancer tissues. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2018;47(8):597–602. Chinese. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5807.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue Y, Yoshimura K, Nishimoto K, et al. Evaluation of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) gene amplification and response to nivolumab monotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2011818. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman AM, Piccioni D, Kato S, et al. Prevalence of PDL1 amplification and preliminary response to immune checkpoint blockade in solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):1237–1244. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedoeem A, Azoulay-Alfaguter I, Strazza M, Silverman GJ, Mor A. Programmed death-1 pathway in cancer and autoimmunity. Clin immunol. 2014;153(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui E, Cheung J, Zhu J, et al. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science. 2017;355(6332):1428–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ning Y, Shen K, Wu Q, et al. Tumor exosomes block dendritic cells maturation to decrease the T cell immune response. Immunol Lett. 2018;199:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poggio M, Hu T, Pai CC, et al. Suppression of exosomal PD-L1 induces systemic anti-tumor immunity and memory. Cell. 2019;177(2):414–27.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin G, Fan X, Zhu W, et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression and tumor infiltrating lymphocyte in surgically resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(48):83986–83994. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YB, Mu CY, Huang JA. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a 5-year-follow-up study. Tumori. 2012;98(6):751–755. doi: 10.1700/1217.13499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper WA, Tran T, Vilain RE, et al. PD-L1 expression is a favorable prognostic factor in early stage non-small cell carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2015;89(2):181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang CY, Lin MW, Chang YL, Wu CT, Yang PC. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression is associated with a favourable immune microenvironment and better overall survival in stage I pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang CY, Lin MW, Chang YL, Wu CT, Yang PC. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in surgically resected stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma and its correlation with driver mutations and clinical outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(7):1361–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velcheti V, Schalper KA, Carvajal DE, et al. Programmed death ligand-1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Lab Invest. 2014;94(1):107–116. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ameratunga M, Asadi K, Lin X, et al. PD-L1 and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes as prognostic markers in resected nSCLC. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Wang L, Li Y, et al. Protein expression of programmed death 1 ligand 1 and ligand 2 independently predict poor prognosis in surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:567–573. doi: 10.2147/ott.S59959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker A, Thakur BK, Weiss JM, Kim HS, Peinado H, Lyden D. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: cell-to-cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(6):836–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt LH, Kümmel A, Görlich D, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in NSCLC indicate a favorable prognosis in defined subgroups. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tokito T, Azuma K, Kawahara A, et al. Predictive relevance of PD-L1 expression combined with CD8+ TIL density in stage III non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;55:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okita R, Maeda A, Shimizu K, Nojima Y, Saisho S, Nakata M. PD-L1 overexpression is partially regulated by EGFR/HER2 signaling and associated with poor prognosis in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2017;66(7):865–876. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-1986-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang K, Wang J, Wei F, Zhao N, Yang F, Ren X. Expression of TLR4 in non-small cell lung cancer is associated with PD-L1 and poor prognosis in patients receiving pulmonectomy. Front Immunol. 2017;8:456. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He Y, Rozeboom L, Rivard CJ, et al. PD-1, PD-L1 protein expression in non-small cell lung cancer and their relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Med Sci Monitor. 2017;23:1208–1216. doi: 10.12659/msm.899909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuma Y, Hishima T, Kashima J, Homma S. High PD-L1 expression indicates poor prognosis of HIV-infected patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2018;67(3):495–505. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2103-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inoue Y, Yoshimura K, Mori K, et al. Clinical significance of PD-L1 and PD-L2 copy number gains in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(22):32113–32128. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeda S, Okamoto T, Okano S, et al. PD-L1 is upregulated by simultaneous amplification of the PD-L1 and JAK2 genes in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]