Abstract

Background

There is continuing public concern about the safety of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. While there is no compelling biological reason to expect that mRNA COVID-19 vaccination (either preconception or during pregnancy) presents a risk to pregnancy, data are limited. It is, however, well documented that SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy is associated with severe illness and increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Among recognized pregnancies in high-income countries, 11–16% end in spontaneous abortion (SAB).

Methods

People enrolled in v-safe, a voluntary smartphone-based surveillance system, who received a COVID-19 vaccine preconception or during pregnancy were contacted by telephone to enroll in the v-safe pregnancy registry. V-safe pregnancy registry participants who received at least one dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine preconception or prior to 20 weeks’ gestation and who did not report a pregnancy loss before 6 completed weeks’ gestation were included in this analysis to assess the cumulative risk of SAB using Life Table methods.

Results

Among 2,456 pregnant persons who received an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine preconception or prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, the cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation was 14.1% (95% CI: 12.1, 16.1%). Using direct age standardization to the selected reference population, the age-standardized cumulative risk of SAB was 12.8% (95% CI: 10.8–14.8%).

Conclusions

When compared to the expected range of SABs in recognized pregnancies, these data suggest receipt of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine preconception or during pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of SAB. These findings add to accumulating evidence that mRNA COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy are safe.

Keywords: pregnancy, spontaneous abortion, COVID-19 vaccine, pregnancy loss, miscarriage, vaccine safety, mRNA vaccine

Introduction

Pregnancy increases the risk for severe COVID-19 illness, and COVID-19 during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of preterm birth and may be associated with increased risk for other adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.1–3 Spontaneous abortion (SAB, often defined as pregnancy loss occurring from 6 to < 20 weeks’ gestation) is a common pregnancy outcome. Risk of SAB is highest in the first 12 weeks, substantially decreasing after the first trimester, and increases significantly with maternal age and co-morbidities.4–7 Among recognized pregnancies in high income countries, 11–16% result in SAB. 4–10

Initial data published from the v-safe pregnancy registry included 104 reports of SAB as of March 30, 2021.11 This report provides additional follow-up data on surviving pregnancies and SABs, in order to provide an estimate of risk. We estimate the cumulative risk of an SAB after receipt of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine preconception or during pregnancy prior to 20 weeks’ gestation to assess whether the risk is in the range of previously reported background rates of SAB.

Methods

Study design

V-safe and the v-safe pregnancy registry have been described previously.11–13 Briefly, v-safe is a smartphone-based tool available for all people who have received a COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Enrollment is voluntary, and participants complete web surveys which include questions about pregnancy status at the time of vaccination and since vaccination.12 Persons who report that they were pregnant at the time of vaccination or since vaccination and are 18 years or older are contacted by telephone and invited to enroll in the v-safe pregnancy registry. Enrolled participants receive a telephone follow-up each trimester, during the postpartum period, and three months following live births.13 This activity was reviewed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy; the activity met requirements of public health surveillance as defined in 45 CFR 46.102.14

Participants

Data were analyzed from participants with a singleton pregnancy who received at least one dose of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine preconception (30 days before the first day of the last menstrual period through 14 days after) or during pregnancy prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, and who had not reported a pregnancy loss before 6 completed weeks’ gestation. The inclusion of participants pregnant at 6 completed weeks’ gestation reflects when pregnancies are generally recognized and is consistent with previous literature estimating SAB in the general population.5, 8–10, 15

Given that the Janssen adenoviral vector COVID-19 vaccine is a different type of vaccine than mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, participants enrolled in the v-safe pregnancy registry who had received the Janssen vaccine (n = 272) were not included in this analysis. At this time, there are limited data available on pregnancy outcomes in these participants because the Janssen vaccine was granted Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) several months after the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed. Gestational age at vaccination was calculated using the self- reported date of vaccination, and either self-reported estimated due date or date of the first day of the last menstrual period. When participants reported an SAB, the date of SAB was recorded based on clinical diagnosis when provided by the participant.

Life table methods were used to calculate the cumulative risk of SAB by gestational week.8, 16 Participants who received an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in the preconception period or before 6 weeks’ of pregnancy were entered into the analysis at 6 weeks’ gestation whereas participants who received their first eligible dose at or after 6 weeks’ gestation entered the analysis in the week they received their first eligible dose. Participants who did not have contact with the v-safe pregnancy registry at or after 20 weeks’ gestation were censored at the time of last contact, and participants who reported other pregnancy outcomes (i.e., ectopic and molar pregnancies, induced abortions) were censored at the date of the outcome. The cumulative risk of SAB for a given gestational week was calculated by taking the product of the week-specific SAB risk and the cumulative risk of SAB at the preceding week for each week up to the week of interest. Log normal confidence intervals were calculated for cumulative risk of SAB at each gestational week. The cumulative SAB risk was also age-standardized using risk of SAB by age group from Magnus et al., 2019.5 Standard errors of the age-adjusted cumulative risk of SAB were estimated by dividing the age-adjusted rate by the square root of the number of SABs, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.17

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to estimate the maximum possible risk of SAB in our cohort by assuming all participants who we were not able to contact in the second trimester experienced an SAB immediately after last contact. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4.

Results

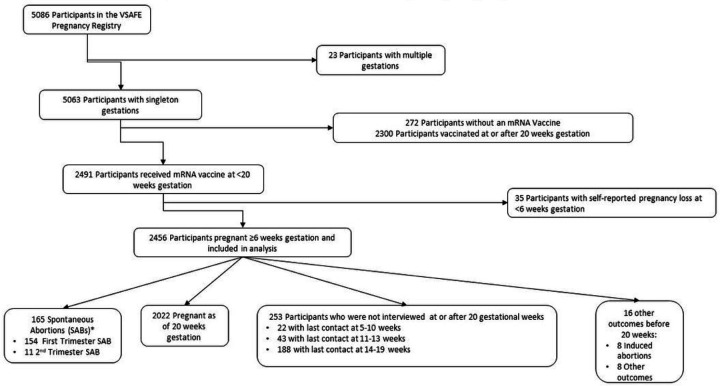

As of July 19, 2021, 5,086 participants were enrolled in the v-safe pregnancy registry, of whom 5,063 reported a singleton pregnancy. Of these, 2,491 participants received at least one mRNA COVID-19 vaccine dose preconception or prior to 20 weeks’ gestation. A total of 35 participants self-reported a pregnancy loss (33 SAB and 2 ectopic pregnancies) at less than 6 weeks’ gestation and were excluded from the analysis. As a result, 2,456 people met criteria for inclusion as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Inclusion Criteria: Receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines preconception and during pregnancy and risk of self-reported spontaneous abortions, CDC v-safe COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry 2020–21

*Percentage of SABs should not be calculated out of total participants included in the analysis and interpreted as a risk. See text for full analysis of SAB risk

The cohort consisted of mostly non-Hispanic white (78.3%) persons who identified as healthcare personnel (88.8%) with most participants aged 30–34 years (49.1%) or 35–39 years (28.2%) (Table 1). Among eligible participants, 27.5% had experienced at least one prior SAB and 9.1% had experienced at least two prior SABs. Over half of participants (52.7%) received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and 47.3% received the Moderna vaccine. Date of first eligible vaccination ranged from December 14, 2020 through April 3, 2021, and 90% of participants received two doses of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

Table 1.

Pregnancy Status at 20 Weeks’ Gestation among Pregnant People Receiving mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in the Preconception Period and through 20 Weeks’ Gestation, CDC v-safe COVID-19 Vaccine Pregnancy Registry: December 14, 2020—July 19, 2021

| All | Self-reported SAB* 6–19 weeks’gestation | Ongoing pregnancies¶ at 20 weeks’ gestation | Participants with ongoing pregnancy at contact prior to 20 weeks’ gestation | Other pregnancy loss 6–19 weeks gestation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n | % | n | %± | N | %± | n | %± | n | %± |

| Total | 2456 | 165 | 2022 | 253 | 16 | |||||

| Age at 1st eligible vaccine dose (years) | ||||||||||

| 20–29 | 432 | 17.6 | 23 | 13.9 | 343 | 17.0 | 64 | 25.3 | 2 | 12.5 |

| 30–34 | 1205 | 49.1 | 71 | 43.0 | 1020 | 50.4 | 108 | 42.7 | 6 | 37.5 |

| 35–39 | 693 | 28.2 | 54 | 32.7 | 561 | 27.7 | 72 | 28.5 | 6 | 37.5 |

| 40+ | 126 | 5.1 | 17 | 10.3 | 98 | 4.8 | 9 | 3.6 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Race and Hispanic origin | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 35 | 1.4 | 5 | 3.0 | 23 | 1.1 | 6 | 2.4 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1923 | 78.3 | 113 | 68.5 | 1613 | 79.8 | 185 | 73.1 | 12 | 75.0 |

| Hispanic | 220 | 9.0 | 21 | 12.7 | 159 | 7.9 | 39 | 15.4 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaskan Native | 7 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 8 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 210 | 8.6 | 17 | 10.3 | 179 | 8.9 | 13 | 5.1 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Non-Hispanic multiple races | 48 | 2.0 | 7 | 4.2 | 34 | 1.7 | 6 | 2.4 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Missing | 5 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Self-reported vaccine priority group | ||||||||||

| Non-healthcare essential worker | 148 | 6.0 | 6 | 3.6 | 110 | 5.4 | 30 | 11.9 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Healthcare personnel† | 2180 | 88.8 | 149 | 90.3 | 1822 | 90.1 | 196 | 77.5 | 13 | 81.3 |

| Vaccine type | ||||||||||

| Moderna | 1162 | 47.3 | 85 | 51.5 | 944 | 46.7 | 126 | 49.8 | 7 | 43.8 |

| Pfizer-BioNTech | 1294 | 52.7 | 80 | 48.5 | 1078 | 53.3 | 127 | 50.2 | 9 | 56.3 |

| Number of vaccine doses reported | ||||||||||

| 1 | 245 | 10.0 | 39 | 23.6 | 183 | 9.1 | 18 | 7.1 | 5 | 31.3 |

| 2 | 2211 | 90.0 | 126 | 76.4 | 1839 | 90.9 | 235 | 92.9 | 11 | 68.8 |

| Timing of Dose 1 | ||||||||||

| Preconception** | 380 | 15.5 | 56 | 33.9 | 212 | 10.5 | 106 | 41.9 | 6 | 37.5 |

| First trimester (>=2 and <14 weeks) | 1230 | 50.1 | 107 | 64.8 | 971 | 48.0 | 142 | 56.1 | 10 | 62.5 |

| Second trimester (>=14 and <20 weeks¶¶) | 846 | 34.4 | 2 | 1.2 | 839 | 41.5 | 5 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Timing of Dose 2 (n=2211) | ||||||||||

| Preconception** | 188 | 8.5 | 19 | 11.5 | 116 | 5.7 | 50 | 19.8 | 3 | 18.8 |

| First trimester (>=2 and <14 weeks) | 885 | 40.0 | 91 | 55.2 | 642 | 31.8 | 145 | 57.3 | 7 | 43.8 |

| Second trimester (>=14 and <28 weeks) | 1125 | 50.9 | 4 | 2.4 | 1081 | 53.5 | 40 | 15.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| After pregnancy outcome | 13 | 0.6 | 12 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Comorbidities and past medical history | ||||||||||

| Obesity±± | 432 | 17.6 | 34 | 20.6 | 340 | 16.8 | 57 | 22.5 | 1 | 6.3 |

| Pre-existing diabetes | 27 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.2 | 23 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Prior SAB | 675 | 27.5 | 59 | 35.8 | 549 | 27.2 | 65 | 25.7 | 2 | 12.5 |

| 1 Prior SAB | 452 | 67.0 | 33 | 20.0 | 373 | 18.4 | 44 | 17.4 | 2 | 12.5 |

| 2 or more Prior SABs | 223 | 33.0 | 26 | 15.8 | 176 | 8.7 | 21 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

Spontaneous abortion

Includes 19 live births, 5 stillbirths, 2 induced abortions after 20 gestational weeks, and 1996 pregnancies ongoing as of last interview

Column percentages provide among each pregnancy outcome/status; these should not be interpreted as risk estimates

Any person serving in a healthcare setting who has the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials

Preconception defined as 4 weeks before last menstrual period up to 2 weeks after

Second trimester vaccination for dose 1 limited to receipt at less than 20 weeks’ gestation per study criteria

12 cases missing information to determine body mass index for obesity

Of the 2,456 participants in the cohort, 2,020 were known to be pregnant at 20 weeks’ gestation. The pregnancy status at 20 weeks’ gestation was unknown for 253 pregnant people (65 could not be contacted for second trimester follow-up and 188 completed second trimester follow-up before 20 weeks’ gestation). A total of 165 participants self-reported an SAB, of which 154 occurred prior to 14 weeks’ gestation.

The week-specific and cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation along with their 95% confidence intervals are tabulated in Table 2. The cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation was 14.1% (95% CI: 12.1–16.1%). When stratified by age, the cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ increased with increasing age: 9.8% (95% CI: 5.9–12.4%) among participants aged 20–29 years, 13.0% (95% CI: 10.1–15.8%) among participants aged 30–34 years, 16.7% (95% CI: 12.5–20.6%) among participants aged 35–39 years, and 28.8% (95% CI: 16.8–39.1%) among participants 40 years and older. Using direct age standardization to the selected reference population2, the age-standardized cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation in the v-safe pregnancy registry was 12.8% (95% CI: 10.8–14.8%) (data not shown). In the sensitivity analysis, under the extreme assumption that all 65 participants with last contact in the first trimester experienced an SAB, the cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation was 18.8% (95% CI: 16.6–20.9%) and was 18.5% (95% CI: 16.1–20.8%) after age standardization (data not shown). Age standardization had less of an effect on our sensitivity analysis than our primary analysis, because participants who were unable to be reached in the second trimester were younger than those with second trimester follow-up (data not shown).

Table 2.

Risk of Spontaneous Abortion among v-safe Pregnancy Registry Participants, December 14, 2020—July 19, 2021

| Gestational Age | Number at risk | Self-reported SAB* | Week-specific SAB* risk (%) | Cumulative SAB risk (%, 95% CI¶) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.0 | 904 | 15 | 1.66 | 1.66 (0.83–2.48) |

| 7.0 | 982 | 18 | 1.83 | 3.46 (2.30–4.61) |

| 8.0 | 1032 | 37 | 3.59 | 6.92 (5.36–8.46) |

| 9.0 | 1087 | 39 | 3.59 | 10.26 (8.44–12.04) |

| 10.0 | 1118 | 19 | 1.70 | 11.79 (9.87–13.66) |

| 11.0 | 1184 | 12 | 1.01 | 12.68 (10.72–14.60) |

| 12.0 | 1274 | 9 | 0.71 | 13.30 (11.31–15.24) |

| 13.0 | 1394 | 5 | 0.36 | 13.61 (11.61–15.57) |

| 14.0 | 1534 | 0 | --- | --- |

| 15.0 | 1632 | 2 | 0.12 | 13.72 (11.71–15.68) |

| 16.0 | 1742 | 2 | 0.11 | 13.81 (11.81–15.78) |

| 17.0 | 1848 | 2 | 0.11 | 13.91 (11.90–15.87) |

| 18.0 | 1941 | 3 | 0.15 | 14.04 (12.03–16.01) |

| 19.0 | 2052 | 2 | 0.10 | 14.12 (12.11–16.09) |

Spontaneous abortion

Confidence interval

Discussion

While SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy is associated with severe illness and adverse obstetrical outcomes1–3, COVID-19 vaccines were not expressly studied in pregnant people prior to availability in the United States under an EUA. While there is no compelling biological mechanism to expect that mRNA COVID-19 vaccines present a risk to pregnancy, data have been limited to guide pregnant people and healthcare professionals about vaccination in the preconception period and during pregnancy. In this report, we calculated the cumulative risk of SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation for people in the v-safe pregnancy registry who received an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine preconception or in pregnancy. These findings add to the accumulating evidence about the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy.11, 18 Previous studies estimating cumulative risk of SAB in the general population have reported similar estimates as our study.4–10 However, the median age of our study population is higher than in the reference studies.7–10 Given that maternal age is a known risk factor SAB, this may have skewed our overall risk of SABs higher. When we age-standardized our estimate, the cumulative risk fell from 14.1% (95% CI: 12.1–16.1%) to 12.8% (95% CI: 10.8–14.8%). Consistent with previous studies that estimated week-specific SAB risk, our week-specific risk of SAB decreased after 12 weeks’ gestation.8, 10

Our sensitivity analysis resulted in an-age standardized risk of 18.5% (95% CI: 16.1–20.8% under the extreme assumption that all 65 pregnant people whom we were unable to contact during the second trimester experienced an SAB. It is possible that some of those not contacted in the second trimester did have an SAB, but it is highly unlikely that all did, especially given that these 65 participants were significantly younger than those with second trimester follow-up. Data in this report are preliminary, and active follow-up through the v-safe pregnancy registry is ongoing. Several limitations should be noted. First, the cohort does not include a comparison group of unvaccinated pregnant people. Additionally, the cohort is relatively homogenous with respect to racial and ethnic groups and occupation with 78% of participants non-Hispanic White and 89% healthcare personnel. Furthermore, data were collected both prospectively and retrospectively. Previous estimates of SAB proportions relied on prospective studies,5,8–10 in which pregnant people were enrolled before or at the start of pregnancy and followed over time to assess pregnancy outcomes, providing less biased estimates. Additionally, all data were self-reported, including vaccine administration dates, pregnancy status, estimated delivery date or gestational age, and pregnancy outcome. Given the voluntary nature of the registry, enrollment biases are likely. Pregnant people who experienced an SAB may have been more likely to enroll in the v-safe pregnancy registry, which would overestimate the risk. Inconsistencies in ability to obtain follow-up information may have also affected the incidence as some may not have been willing to complete their scheduled follow-up interviews if they experienced an SAB. Our sensitivity analysis accounted for that possibility.

Despite the limitations noted above and the inherent challenges of registry data without a comparison group, these data suggest that the cumulative risk of an SAB from 6–19 weeks’ gestation after receipt of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine is within the expected range based on previous SAB studies. Confirmation of these results is needed from observational studies that include unvaccinated pregnant people. Our data as of July 19, 2021 are reassuring and do not suggest an increased risk of SAB following receipt of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in the preconception period or during pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the v-safe participants for their participation in the v-safe pregnancy registry and the members of the CDC COVID-19 Response Team for their support and contributions. We would also like to thank the members of the CDC v-safe COVID-19 Pregnancy Registry Team: Amena Abbas, M.P.H.1,2, Amanda Akosa, M.P.H.3, Dayna S. Alexander, Ph.D.4, Kathryn E. Arnold, M.D.3, Jamal Bankhead, Dr.P.H.5, Tabatha Barber, Ph.D.6, Amy Blum, M.H.S.A.7, Ellen Boundy, Sc.D.8, Virginia B. Bowen, PhD.9, Kailyn M. Brooks, M.P.H.2,10, Cheryl Broussard, Ph.D.3, Tara Brown, M.P.H.11, Veronica K. Burkel, M.P.H.3, Gyan Chandra, M.S.10, Karen Chang, Ph.D.12, Dena Cherry-Brown, M.P.H.3, Monica DiRienzo, M.A.13, Tuyen Do, B.S.C.S.14, Charise Fox, M.P.H.2,3, Julianne M. Gee, M.P.H.15, Robbie Gray, A.S.16, Caitlin J. Green, M.P.H.3, Jennifer Hamborsky, M.P.H.17, Anne M. Hause, Ph.D.15, Jennifer Hegle, M.P.H.18, Obehi Ilenikhena, M.P.H.19, Jessly Joy, M.P.H.20, Ashley Judge, M.P.H.2,3, Alaya Koneru, M.P.H.17, Zanie Leroy, M.D.21, Birook Mekonnen, M.P.H.2, 13, Anne Moorman, M.P.H.22, Pedro L. Moro, M.D.15, John F. Nahabedian III, M.S.3, Morgan Nail, B.S.2, 23, Andrea Neiman, Ph.D.1, Kimberly Newsome, M.P.H.13, Suzanne Newton, M.P.H. 3, Keydra Phillips Oladapo, Ph.D.5, Nicole S. Olgun, Ph.D.6, H. Pamela Pagano, Dr.P.H.10, Lakshmi Panagiotakopoulos, M.D.22, Youngjoo Park, M.P.H.2,3, Corrine Parker, Pharm.D.12, Kara Polen, M.P.H.3, Emmitt Rathore, B.S.3, Tom T. Shimabukuro, M.D.15, Penelope Strid, M.P.H.10, Jennifer M. Swanson, M.P.H.18, Ayzsa F. Tannis, M.P.H.2,3, Naomi K. Tepper, M.D.3, Letha Thomas, Ph.D.18, Lindsey A. Torre, M.S.P.H18, Emmy L. Tran, Pharm.D.3, Susanna L. Trost, M.P.H.2,10, Diana Valencia, M.S.3, Jennifer L. Wilkers, M.P.H.2, 10, Luke Yip, M.D.24, and Sarah Zohdy, Ph.D25. We would also like to thank Ronghui (Lily) Xu, Ph.D.26, and Margaret Honein, Ph.D.12, for their statistical analysis consultation. This project was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Affiliations:

1Division of Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 2Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education; 3Division of Birth Defects and Infant Disorders, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; 4Division of Diabetes and Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 5 Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB prevention; 6Health Effects Laboratory Division, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, CDC; 7Division of Health Care Statistics, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC; 8Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 9Division of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Vital Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention, CDC; 10Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 11Division of Viral Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; 12Division of Preparedness and Emerging Infections, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 13Division of Human Development and Disability, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, CDC; 14 Office of the Director, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 15Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, CDC; 16Office of the Chief Operating Officer, Office of the Director, CDC; 17Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC; 18Division of Global HIV and TB, Center for Global Health, CDC; 19Division of Performance Improvement and Field Services, Center for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support, CDC;20Division of Analysis and Epidemiology, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC; 21Division of Population Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 22Division of Viral Hepatitis, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC; 23Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health, CDC; 24National Center for Environmental Health/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Office of Emergency Management, CDC; 25Division of Parasitic Disease Malaria, Center for Global Health, CDC; 26Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, Department of Mathematics, University of California San Diego.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mention of a product or company name is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the CDC or the FDA. All authors are U.S. government employees or U.S. government contractors and do not have any material conflicts of interest.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Lauren Head Zauche, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Bailey Wallace, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Ashley N. Smoots, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Christine K. Olson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Titilope Oduyebo, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Shin Y. Kim, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Emily E. Peterson, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Jun Ju, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jennifer Beauregard, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Allen J. Wilcox, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

Charles E. Rose, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Dana Meaney-Delman, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Sascha R. Ellington, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Zambrano LD, Ellington SR, Strid P, et al. Update: Characteristics of symptomatic women of reproductive age with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by pregnancy status — United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR. 2020;69:1641–1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei SQ, Bilodeau-Bertrand M, Liu S, Auger N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ, 2021; 193(16):E540–E548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossen LM, Ahrens KA, Branum AM. Trends in risk of pregnancy loss among US women, 1990–2011. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2018;32(1):19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnus MC, Wilcox AJ, Morken NH, Weinberg CR, Haberg SE. Role of maternal age and pregnancy history in risk of miscarriage: prospective register based study. BMJ. 2019; 364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang K, Neuvo-Chiquero A. Trends in self-reported spontaneous abortions: 1970–2000. Demography. 2012; 49(3): 989–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linnakaari R, Helle N, Mentula M, et al. Trends in the incidence, rate, and treatment of miscarriage- nationwide registry-study in Findland, 1998–2016. Hum Reprod. 2019; 34 (11): 2120–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ammon Avalos L, Galindo C, Li DK. A systematic review to calculate background miscarriage rates using life table analysis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(6):417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox AJ. Fertility and Pregnancy - An Epidemiologic Perspective, Oxford Univ Press, 2010. p 152 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldhaber MK, Fireman BH. The fetal life table revisited: Spontaneous abortion rates in three Kaiser Permenente cohorts. Epidemiology. 1991; 2(1): 33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384: 2273–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. V-safe active surveillance for COVID-19 vaccine safety. January 2021. Accessed June 15, 2021. https:/www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/pdf/V-safe-protocol-508.pdf.

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. V-safe pregnancy surveillance (amendment). 2021. Accessed June 15, 2021. https:/www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/pdf/vsafe-pregnancy-surveillance-protocol-508.pdf.

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services – 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. Sect. 241(d); 5 U.S.C. Sect. 552a; 44 U.S.C. Sect. 3501 et seq. Accessed June 17, 2021. https:/www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdf.

- 15.Wang et al. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertility and Sterility. 2003; 79(3): 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu R, Chambers C. A sample size calculation for spontaneous abortion in observational studies. Reproductive Toxicology. 2011; 32: 490–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keyfitz N. 3.Sampling variance of standardized mortality rates. Hum Biol. 1966;38(3):309–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldshtein I, Nevo D, Steinberg DM, et al. Association between BNT162b2 accination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA. Published onlineJuly12, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]