Abstract

Background

The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) determined the etiologic agents of moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) in children under 5 years old in Africa and Asia. Here, we describe the prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of nontyphoidal Salmonella (NTS) serovars in GEMS and examine the phylogenetics of Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 isolates.

Methods

Salmonella isolated from children with MSD or diarrhea-free controls were identified by classical clinical microbiology and serotyped using antisera and/or whole-genome sequence data. We evaluated antimicrobial susceptibility using the Kirby-Bauer disk-diffusion method. Salmonella Typhimurium sequence types were determined using multi-locus sequence typing, and whole-genome sequencing was performed to assess the phylogeny of ST313.

Results

Of 370 Salmonella-positive individuals, 190 (51.4%) were MSD cases and 180 (48.6%) were diarrhea-free controls. The most frequent Salmonella serovars identified were Salmonella Typhimurium, serogroup O:8 (C2-C3), serogroup O:6,7 (C1), Salmonella Paratyphi B Java, and serogroup O:4 (B). The prevalence of NTS was low but similar across sites, regardless of age, and was similar among both cases and controls except in Kenya, where Salmonella Typhimurium was more commonly associated with cases than controls. Phylogenetic analysis showed that these Salmonella Typhimurium isolates, all ST313, were highly genetically related to isolates from controls. Generally, Salmonella isolates from Asia were resistant to ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone, but African isolates were susceptible to these antibiotics.

Conclusions

Our data confirm that NTS is prevalent, albeit at low levels, in Africa and South Asia. Our findings provide further evidence that multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 can be carried asymptomatically by humans in sub-Saharan Africa.

Keywords: moderate-to-severe-diarrhea (MSD), Salmonella, antibiotic susceptibility, serovars, gastroenteritis

In agreement with prior studies, we show that nontyphoidal Salmonella is prevalent in stool of children <5 years, albeit at low levels, in Africa and South Asia and Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 can be carried asymptomatically by humans in sub-Saharan Africa.

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovars Typhi (Typhi), Paratyphi A (Paratyphi A), and Paratyphi B sensu stricto (Paratyphi B) cause enteric fever, while nontyphoidal Salmonella (NTS) generally causes self-limited gastroenteritis in healthy individuals. However, in young infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised hosts, NTS can lead to bacteremia resulting in hospitalization and death [1]. In some resource-limited countries, NTS is a recognized etiologic agent of diarrhea [2–5] and an important risk factor for diarrhea-related morbidity and mortality in children [6]. In 2015, an estimated 37 410 children died as a result of NTS gastroenteritis, with a large burden of disease in Southeast Asia and South Asia [7]. Serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis are the most common NTS isolated from cases of gastroenteritis worldwide. Despite the capacity to isolate Salmonella by stool culture, little is known about the prevalence of NTS serovars that cause gastroenteritis in Africa and South Asia.

Invasive NTS (iNTS) causes bacteremia in sub-Saharan Africa, occurring predominantly in infants, toddlers, as well as in malnourished or malaria-infected adults and/or those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [8, 9]. Although the incidence of iNTS has declined in many sites across Africa [10], it is still one of the most common causes of bloodstream infections in African children [11]. Interestingly, unique clades of serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis are associated with bacteremia in this region [8, 12, 13]. Most of the Typhimurium strains isolated from blood in sub-Saharan Africa belong to multi-locus sequence type (ST) 313 [14]. In contrast, the most common genotype isolated worldwide is ST19, which is generally associated with gastroenteritis [15] but has recently been reported as a primary cause of invasive infections in a study in Uganda [16]. Both ST19 and ST313 genotypes have been isolated from patients with either gastroenteritis or bacteremia in Kenya, although the number of diarrhea cases was low [17].

The use of antibiotics to treat uncomplicated NTS gastroenteritis in children is not recommended, except where progression to invasive disease is a risk [18, 19]. However, information about the antimicrobial susceptibility of NTS is useful as this knowledge contributes to our overall understanding of resistance markers that are circulating in specific geographic locations. In fact, NTS harboring antimicrobial resistance traits in the gastrointestinal tract could serve as a reservoir for iNTS [20]. Presently, countries with the highest burden of iNTS disease report 48–75% multidrug resistance to commonly used antibiotics, a major concern given that more-effective third-generation cephalosporins or fluoroquinolones may be less available or more costly in these settings [11, 21].

During 2007–2010, the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) determined the etiologic agents of moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) in children 0–59 months old living in The Gambia, Mali, Mozambique, Kenya, India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan [22]. This large, prospective, case-control study determined that NTS was significantly associated with MSD in infants (0–11 months) from the Bangladesh site and toddlers (12–23 months) and young children (24–59 months) from the Kenya site [22]. Here, we determined the prevalence of Salmonella serovars isolated in GEMS, evaluated antimicrobial susceptibility, identified Typhimurium sequence types, and examined the phylogenetic relatedness of Typhimurium ST313 isolates.

METHODS

GEMS Study Participants

The methods and main findings from GEMS have previously been described [22–24]. Briefly, GEMS participants were recruited from censused populations during 2007–2010 in The Gambia, Mali, Mozambique, Kenya, Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. Study participants included children aged 0–59 months of age with MSD who presented to a sentinel health facility (see Supplementary Methods for additional details). Children were recruited into 0–11-, 12–23-, and 24–59-month age groups. For each child with MSD (case) enrolled, 1–3 children without diarrhea during the previous week (controls) were recruited. Scientific and ethics committees and institutional review boards of participating institutions in each country as well as the coordinating institution, University of Maryland, Baltimore, approved the study protocol prior to implementation. Informed consent was obtained in the local dialect from all participating caretakers before recruitment of their children into the study.

Detection of Salmonella spp.

A panel of enteropathogens was identified from stool specimens, collected at the clinic from MSD cases or obtained at home by caregivers of children in the control group, as previously described [24]. Salmonella spp. were shipped to the Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health (CVD) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine for additional characterization.

Characterization of Salmonella Serovars From Stools

At CVD, Salmonella spp. were agglutinated using polyvalent O and O1 antisera followed by serogroups O:2 (A), O:4 (B), O:6,7 and O:7 (C1), O:6,8 and O:8 (C2-C3), O:9 (D1), O:9,46 (D2), O:3,10 (E1), O:11 (F), and O:13 (G) antisera (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan). Serovars Typhimurium, Typhi, Enteritidis, and Paratyphi B were fully serotyped (using O and H typing antisera) and additionally confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [25, 26].

Sequence Typing of Typhimurium Isolates

Sequence types were determined for all 87 Typhimurium isolates using multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) by PCR and sequencing and/or by examining whole-genome sequences. Sequence typing by MLST followed methodology described previously [15].

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

The majority of the Salmonella isolates (355 out of 370) were subjected to whole-genome sequencing. Following sequencing, 120 isolates were excluded from subsequent analyses as they did not meet the quality-control criteria. Details of sequencing and phylogenetic analyses are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

The susceptibility of the 370 Salmonella isolates to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), gentamicin, and ceftriaxone was determined using the Kirby-Bauer disk-diffusion method and interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. Multidrug resistance was defined as resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and TMP/SMX. To assess whether the high resistance of NTS to antimicrobials was associated with antibiotic prescription rate, we determined the percentage of children with MSD (and Salmonella isolated in stools) who had been prescribed (but may or may not have been given) antimicrobial agents after visiting any of the sentinel health facilities that participated in GEMS.

Statistical Analysis

To determine which individual Salmonella serovars were driving the association between Salmonella and MSD that was found in the original GEMS analyses [22], we used the same conditional logistic regression model as previously described [27]. Instead of including Salmonella species in the model we included variables for each Salmonella serogroup/serovar. The association of each serovar with MSD was adjusted for other co-pathogens. The rationale for this approach, generally, and in the unique context of GEMS, has been discussed previously [27]. Analyses were conducted using R version 3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Participants With Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea

Of the cases with Salmonella identified, 86 (44%) were in the 0–11-month age group, 55 (29%) were in the 12–23-month age group, and 49 (26%) were in the 24–59-month age group (Table 1). Cases experienced severe signs of MSD. Approximately 20% of infants with Salmonella spp. detected had bloody diarrhea, while 100% of children aged 12–59 months old with Salmonella spp. produced watery diarrhea. Of note, a lower proportion of children with MSD who had Salmonella isolated tended to be female in all age groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children With Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea and From Whom Salmonella Were Isolated

| Clinical Signs and Symptoms | 0–11 Months (n = 86) | 12–23 Months (n = 55) | 24–59 Months (n = 49) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stool consistency | |||

| Mucus | 72.94 | 61.82 | 53.06 |

| Pus | 3.49 | 9.09 | 12.24 |

| Bloody | 24.42 | 12.73 | 0 |

| Watery | 75.58 | 87.27 | 100 |

| Medical history | |||

| Vomiting >3 times/day | 40.70 | 40.0 | 48.98 |

| Drank much less than usual | 19.77 | 21.82 | 14.29 |

| Very thirsty | 59.3 | 67.27 | 83.33 |

| Decreased activity or lethargy | 36.05 | 54.55 | 53.06 |

| Irritable or restless | 45.35 | 61.82 | 55.10 |

| Fever >38°C or parent perception | 73.26 | 72.73 | 77.55 |

| Physical examination | |||

| Admitted to the hospital | 17.44 | 18.18 | 22.45 |

| Undernutrition | 9.30 | 16.36 | 12.24 |

| Loss of skin turgor | 26.74 | 25.45 | 36.73 |

| Dry mouth | 54.65 | 74.55 | 81.63 |

| Sunken eyes | 65.12 | 85.45 | 87.76 |

| Axillary temperature >38.3°C | 18.60 | 21.82 | 26.53 |

| Gender | |||

| Female gender | 37.21 | 45.45 | 40.82 |

Data are presented as percentages.

Geographical Distribution and Prevalence of Salmonella Serovars

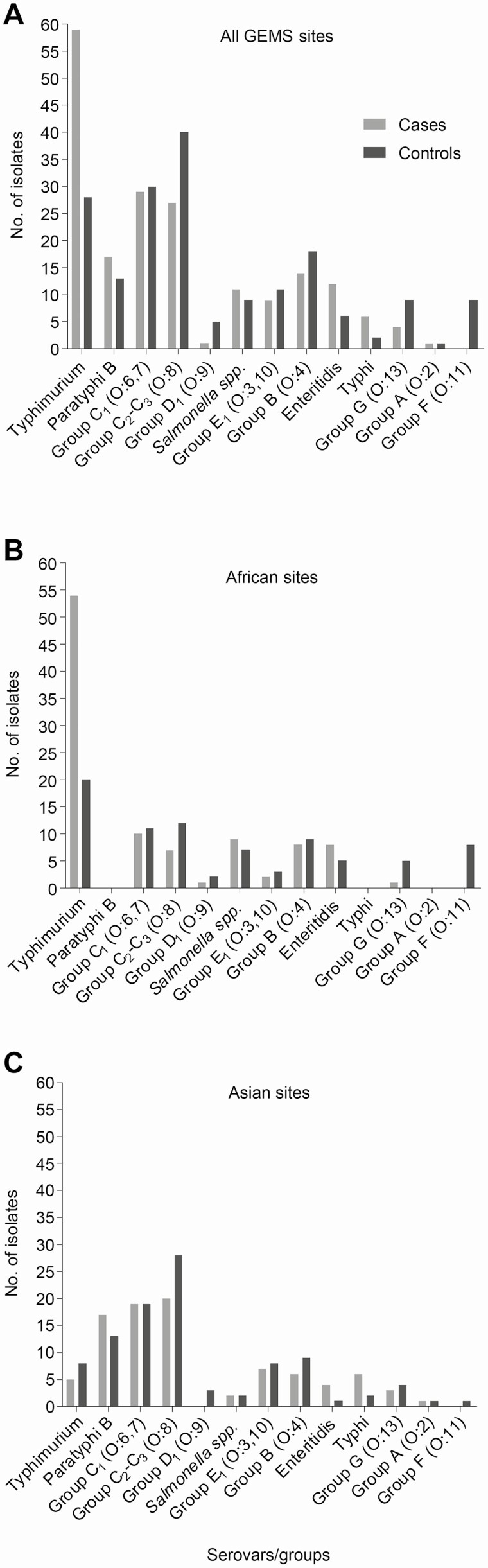

The serovar distribution of the 370 Salmonella isolates (190 from cases and 180 from controls) collected from stools of study participants is shown in Figure 1. Of these, 361 were NTS. Additionally, we recovered 8 Typhi from Asia and 1 Paratyphi A isolate from Bangladesh. The most frequent NTS serovars identified were Typhimurium, serogroup O:8 (C2-C3), serogroup O:6,7 (C1), Paratyphi B Java, and serogroup O:4 (other than Typhimurium or Paratyphi B). Serovar Typhimurium predominated in Africa, whereas serogroup O:6,7 (C1) and O:8 (C2-C3) serovars were the most common in Asia.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Salmonella serogroups and serovars isolated from MSD cases and diarrhea-free asymptomatic controls. Salmonella spp. isolated from stools at (A) all 7 GEMS sites, (B) Africa, and (C) Asia. Abbreviations: GEMS, Global Enteric Multicenter Study; MSD, moderate-to-severe diarrhea.

Prevalence of Salmonella Serovars by Site and Age Stratum

The prevalence of the most abundant serovars isolated in GEMS, as well as serovar Enteritidis (due to its importance in iNTS disease in Africa), is shown in Table 2. The individual serovars of isolates are listed in Supplementary Table 1. In general, we found that the rates of NTS isolation were low (≤5.3%) in both cases and controls regardless of age groups, although some site-to-site variation was apparent. At the Kenya site, serovar Typhimurium, the most prevalent serovar, was recovered in stools of MSD cases at a rate of 3.3% for infants, 3.7% for toddlers, and 4.3% for young children. In Bangladesh, Paratyphi B Java, the most prevalent serovar there, was recovered from 2.0% of infants with MSD. Serogroup O:8 (C2-C3) organisms were most prevalent in stools at the Pakistan site. The prevalence of NTS in cases and controls in The Gambia, Mali, Mozambique, and India was less than 1.5%.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Nontyphoidal Salmonella at GEMS Sites Among Children With Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea (Cases) and Controls

| Basse, The Gambia | Bamako, Mali | Manhica, Mozambique | Nyanza Province, Kenya | Kolkata, India | Mirzapur, Bangladesh | Karachi (Bin Qasim Town), Pakistan | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of NTS | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls |

| 0–11 Months | ||||||||||||||

| No. of participants | 400 | 585 | 727 | 727 | 374 | 697 | 673 | 673 | 672 | 685 | 550 | 878 | 633 | 633 |

| No. of NTS (%) | 5 (1.3) | 12 (2.1) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 34 (5.1) | 29 (4.3) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (1.5) | 27 (4.9) | 14 (1.6) | 15 (2.4) | 24 (3.8) |

| Typhimurium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 (3.3) | 9 (1.3) | 0 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Enteritidis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paratyphi B Java | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 11 (2.0) | 8 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

| Serogroup O:4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Serogroup O:6,7 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 9 (1.6) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) |

| Serogroup O:8 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | 7 (1.1) | 13 (2.1) |

| Other serovars | 4 (1.0) | 9 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 6 (0.9) | 0 | 5 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 4 (0.6) |

| 12–23 Months | ||||||||||||||

| No. of participants | 455 | 639 | 682 | 695 | 195 | 391 | 410 | 621 | 588 | 598 | 476 | 761 | 399 | 676 |

| No. of NTS (%) | 6 (1.3) | 8 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 24 (5.9) | 21 (3.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) | 7 (1.5) | 9 (1.2) | 14 (3.5) | 19 (2.8) |

| Typhimurium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 (3.7) | 6 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) |

| Enteritidis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Paratyphi B Java | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Serogroup O:4 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| Serogroup O:6,7 | 2 (0.4) | 4 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 4 (0.6) |

| Serogroup O:8 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.7) | 4 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 4 (0.5) | 4 (1.0) | 7 (1.0) |

| Other serovars | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (1.5) | 2 (0.3) |

| 24–59 Months | ||||||||||||||

| No. of participants | 174 | 345 | 624 | 642 | 112 | 208 | 393 | 589 | 308 | 731 | 368 | 826 | 226 | 529 |

| No. of NTS (%) | 4 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 (5.1) | 11 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.3) | 7 (2.2) | 6 (0.7) | 10 (5.8) | 10 (2.3) |

| Typhimurium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 (4.3) | 5 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) |

| Enteritidis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paratyphi B Java | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Serogroup O:4 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) |

| Serogroup O:6,7 | 3 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) |

| Serogroup O:8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Other serovars | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (3.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Total participants (all ages) | 1029 | 1569 | 2033 | 2064 | 681 | 1296 | 1476 | 1883 | 1568 | 2014 | 1394 | 2465 | 1258 | 1838 |

| Total no. of NTS (all ages) (%) | 15 (1.5) | 20 (1.3) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 5 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | 78 (5.3) | 61 (3.2) | 3 (0.2) | 14 (0.7) | 41 (2.9) | 29 (1.2) | 39 (3.1) | 53 (2.9) |

Abbreviations: GEMS, Global Enteric Multicenter Study; NTS, nontyphoidal Salmonella.

Salmonella Serovars Significantly Associated With Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea

Previously, 3.2% and 3.7% of MSD episodes in toddlers (12–23 months) and children (24–59 months) at the Kenya site, respectively, and 4.6% of MSD episodes in infants at the Bangladesh site were shown to be attributable to Salmonella [22]. We determined the serovars driving the associations by using a conditional logistic regression model (Supplementary Table 2). In Bangladesh, serogroup O:6,7 (C1) (odds ratio [OR], 6.4; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.84–22.58), O:8 (C2-C3) (OR, 6.0; 95% CI: 1.28–28.33), and serovar Paratyphi B Java (OR, 4.8; 95% CI: 1.87–12.29) were significantly associated with MSD. In Kenya, the association was driven by serovar Typhimurium among children aged 12–23 months (OR, 4.3; 95% CI: 1.86–9.93) and 24–59 months (OR, 4.9; 95% CI: 2.09–11.64). All other serovars occurred in too few cases and controls to produce significant results.

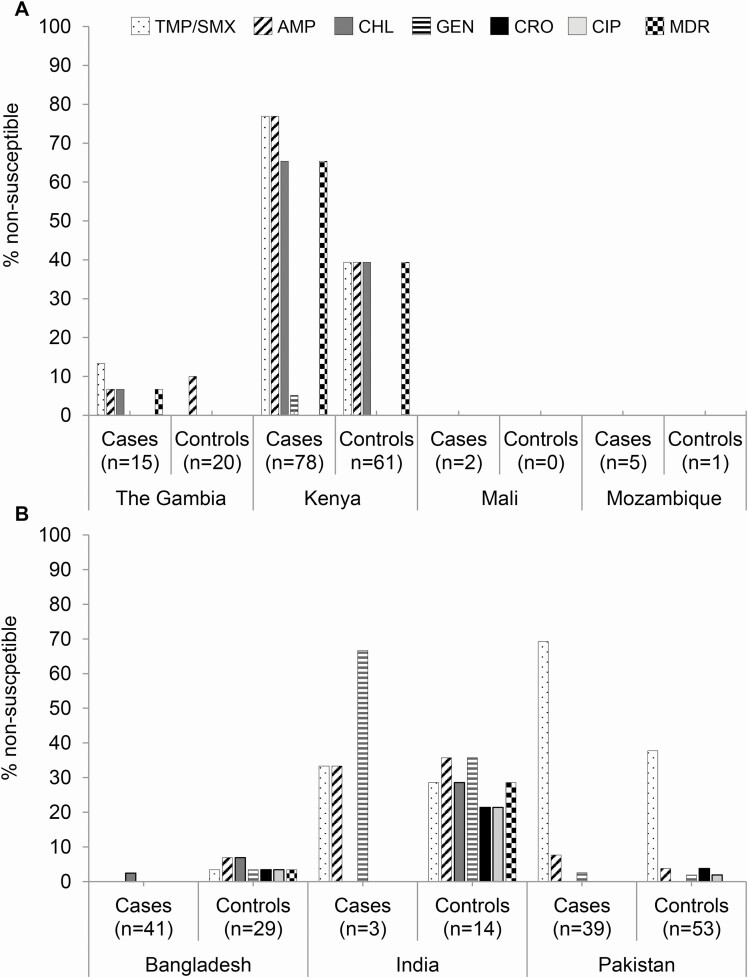

Antimicrobial Susceptibility at GEMS Sites

Salmonella isolates from the African and Asian sites differed in terms of their antimicrobial susceptibility (Figure 2). Isolates from Africa were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone, whereas resistance to these antibiotics was observed among Asian NTS isolates. We observed 65.4% of NTS from MSD cases in Kenya to be multidrug resistant (MDR) to ampicillin, TMP/SMX, and chloramphenicol. However, isolation of nonsusceptible NTS was less frequent at the site in The Gambia; only 6.7% of NTS from cases showed an MDR phenotype (Figure 2A). In Asia, Indian isolates showed more resistance to the antibiotics tested than isolates from the other 2 Asian sites (Figure 2B). We observed antimicrobial susceptibility profiles among NTS from controls that were similar to cases at each site except for Kenya and India.

Figure 2.

Percentage of NTS nonsusceptible to any of 6 commonly used antimicrobial agents. NTS isolated from (A) Africa and (B) Asia. Abbreviations: AMP, ampicillin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CRO, ceftriaxone; GEN, gentamicin; MDR, multidrug resistant; NTS, nontyphoidal Salmonella; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

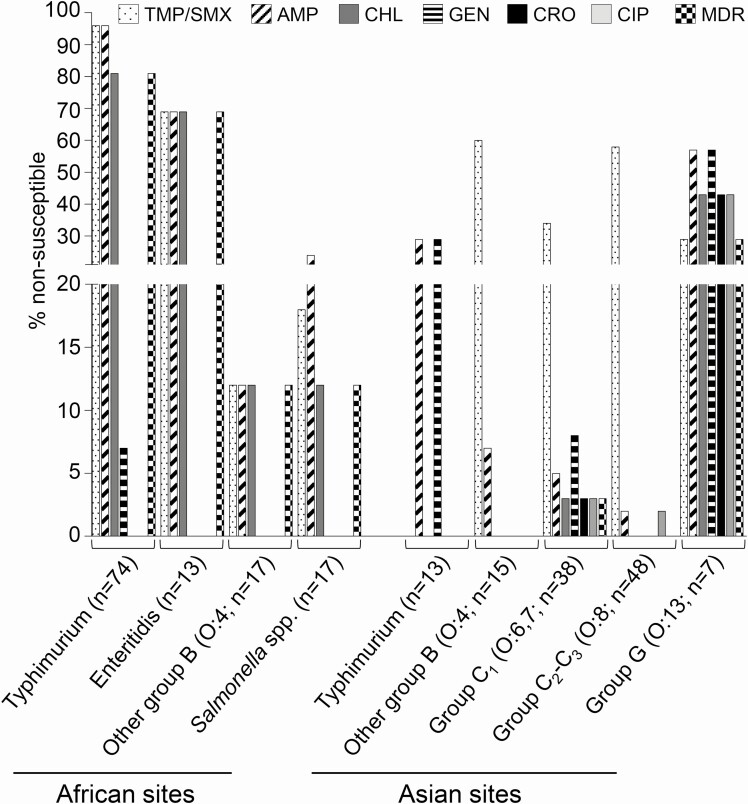

Serovars Typhimurium and Enteritidis from Africa and serogroup O:6,7 (C1) and serogroup O:13 (G) isolates from Asia showed the highest percentage of antimicrobial resistance (Figure 3). All Enteritidis and Paratyphi B Java isolates recovered from GEMS stools from Asia were pan-susceptible to antimicrobial agents, while the 6 serogroup O:13 (G) isolates from Africa were pan-susceptible. Five of the 8 (62.5%) serovar Typhi from Asia (Pakistan and India) were MDR.

Figure 3.

Percentage of NTS that were nonsusceptible to 6 antibiotics by serotype or serogroup. Only serotypes or serogroups that showed nonsusceptibility to antibiotics are shown. Abbreviations: AMP, ampicillin; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CRO, ceftriaxone; GEN, gentamicin; MDR, multidrug resistant; NTS, nontyphoidal Salmonella; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

In general, most MSD cases with Salmonella had been prescribed or given an antibiotic (except in Pakistan) (Table 3). Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic in Africa, whereas ciprofloxacin was the most common in Asia.

Table 3.

Proportion of Children With Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea and Positive for Salmonella Prescribed Any Antimicrobial Agents After Seeking Care at Sentinel Health Facilities That Participated in GEMS at Sites in Africa and Asia

| Africa | The Gambia | Mali | Mozambique | Kenya | Asia | India | Bangladesh | Pakistan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of casesa | 100 | 15 | 2 | 5 | 78 | 90 | 5 | 42 | 43 |

| No antibiotics prescribed/given, n (%) | 23 (23.0) | 4 (26.7) | 0 | 0 | 19 (24.4) | 36 (40.0) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 35 (81.4) |

| Any antibiotics prescribed/given, n (%) | 77 (77.0) | 11 (73.3) | 2 (100) | 5 (100) | 59 (75.6) | 54 (60.0) | 5 (100) | 41 (97.6) | 8 (18.6) |

| Antimicrobial agent, n (%) | |||||||||

| Ampicillinb | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chloramphenicolb | 6 (6.0) | 3 (20.0) | 0 | 3 (60.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ciprofloxacin/other fluoroquinoloneb | 5 (5.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 4 (5.1) | 43 (47.8) | 4 (80.0) | 31 (73.8) | 8 (18.6) |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazoleb | 59 (59.0) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (100) | 1 (20.0) | 48 (61.5) | 6 (6.7) | 1 (20.0) | 5 (11.9) | 0 |

| Gentamicinb | 12 (12.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (40.0) | 10 (12.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Amoxicillin | 4 (4.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (20.0) | 2 (2.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Azithromycin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4.4) | 0 | 4 (9.5) | 0 |

| Erythromycin | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 0 |

| Penicillin | 9 (9.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (40.0) | 7 (9.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Selexid/pivmecillinam | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other macrolides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviation: GEMS, Global Enteric Multicenter Study.

aTotal number of cases with moderate-to-severe diarrhea who were prescribed or given any antimicrobial agent at any participating sentinel health facility.

bAntimicrobial agents that were tested for susceptibility.

Phylogenetic Analysis of Salmonella Typhimurium

Since Typhimurium was the most important cause of iNTS disease at several GEMS sites and was the most frequent serovar isolated from stools, a phylogenetic analysis was performed. Of 87 Typhimurium isolates, 74 (85.0%) were from Africa (Kenya), while 13 (14.9%) were from Asia (Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh). Table 4 shows the sequence types (ST) of these Typhimurium isolates listed by site of origin.

Table 4.

Sequence Types of Typhimurium Isolates Identified in GEMS Stools Determined Using Multi-Locus Sequence Typing Polymerase Chain Reaction and/or Whole-Genome Sequencing

| Sequence Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | ST36 | ST313 | Total |

| Africa | 0 | 74 | 74 |

| Kenya | 0 | 74 | 74 |

| Asia | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| Bangladesh | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Pakistan | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| India | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| All sites | 9 | 78 | 87 |

Abbreviations: GEMS, Global Enteric Multicenter Study; ST, sequence type.

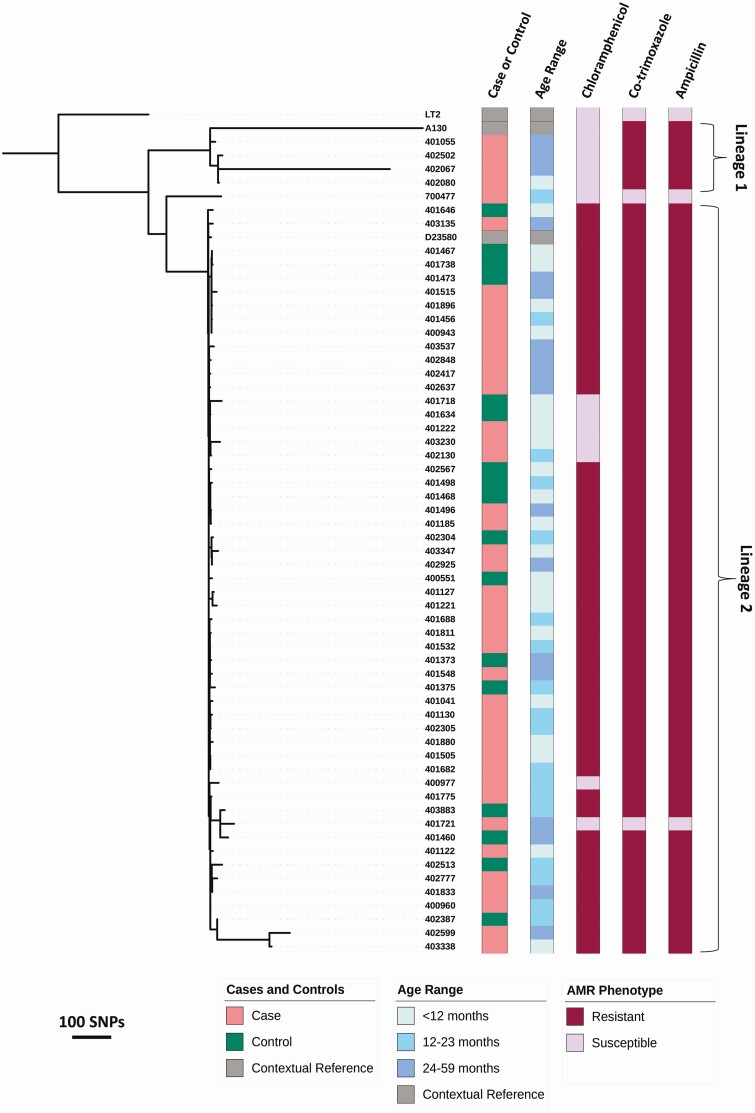

A phylogeny was constructed using whole-genome sequences to determine the relationship between the Typhimurium ST313 isolates from MSD cases and controls (Figure 4). The African ST313 sequence type has been divided into the older lineage 1 isolates and the more recent lineage 2 [13, 28]. Here, 50 of 55 study isolates analyzed (90.9%) clustered with the ST313 lineage 2 reference genome D23580, 49 of 55 (89%) of which showed the typical MDR phenotype associated with lineage 2, namely resistance to chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, and ampicillin. The lineage 2 isolates from the MSD cases and diarrhea-free controls were closely related and could not be distinguished phylogenetically. A group of 5 isolates in stools of cases and controls, regardless of age, formed a small lineage 2 subcluster associated with susceptibility to chloramphenicol.

Figure 4.

Genetic relationship between Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 isolated from MSD cases and diarrhea-free controls. The core genome maximum likelihood tree is shown for Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 isolated from the stool of cases and controls of children aged under 5 years in Kenya and Pakistan (1 isolate), which were collected as part of the GEMS. Scale bars in SNPs are shown beneath the phylogeny. Patient group, age range, and AMR data for the isolates are displayed using color strips created using Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL; Biobyte Solutions, Heidelberg, Germany) and are labeled and colored according to the in-laid key. Isolates that cluster with the lineage 1 or lineage 2 reference genomes are indicated. The tree is rooted using ST19. Abbreviations: AMR, antimicrobial resistance; GEMS, Global Enteric Multicenter Study; MSD, moderate-to-severe diarrhea; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; ST, sequence type.

Four of the 55 isolates (7%) clustered with the ST313 lineage 1 reference genome A130, all of which were isolated from MSD cases in Kenya and were sensitive to chloramphenicol. Of note, the 1 study isolate (specimen 700477) that failed to cluster with lineage 1 or lineage 2 and demonstrated pan-susceptibility to antibiotics was isolated from a case of MSD from Pakistan.

DISCUSSION

Salmonella isolates were detected in stools of children with MSD and from diarrhea-free community controls at each of the GEMS sites. A primary finding of our analysis was that, except for Typhimurium, the prevalence of most Salmonella serovars was similar in stools of cases and controls, regardless of age and across study sites. Because children enrolled as controls in GEMS only had to have been free of diarrhea for the previous 7 days, we could not rule out asymptomatic carriage or shedding of Salmonella among controls due to persistent excretion or convalescence [29]. Nontyphoidal Salmonella are reportedly excreted for longer periods in children than adults, lasting from several weeks to months [18, 30]. We found that NTS was as prevalent in cases as in controls, which suggests that NTS is endemic at the 7 GEMS sites [3, 31, 32].

In this study, we report the association of Typhimurium ST313 with acute diarrhea in Kenya using a conditional logistic regression model, showing that these bacteria cause diarrhea and are not just associated with invasive disease. This observation is supported by recent studies from Kenya, the Central African Republic, and Democratic Republic of Congo, which also detected Typhimurium ST313 in stool [17, 33, 34]. Typhimurium ST313 was identified in both MSD cases and controls, confirming that this important sequence type can be carried asymptomatically by humans. Phylogenetic analysis identified lineages 1 and 2, in accordance with previous findings [28]. We found that the same ST313 lineage (lineage 2) was prevalent in the stools of both MSD cases and controls. The fact that isolates from cases and controls are found in every part of the phylogeny suggests that the Typhimurium isolates that cause MSD are closely related to those associated with asymptomatic carriage; NTS carriage has been reported elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa [34–36].

Several groups have attempted to identify the reservoir of iNTS isolates in Africa. Kariuki et al [20] were the first to suggest that these bacteria are not acquired zoonotically but are acquired by anthroponotic transmission. In this and other studies, NTS isolated from blood cultures of bacteremic index cases were highly similar to isolates from household contacts but different from NTS from animal or environmental sources taken from around the homes of index cases [20, 36]. Collectively, these prior studies suggest that the reservoir for Typhimurium ST313 is indeed humans. It remains possible that the lack of detection of Salmonella spp. from animals and the environment reflects difficulties in culture from these specimen types. However, if the inference from the above-mentioned studies is correct, our data would support these findings by showing that Typhimurium strains isolated from stools of cases and controls in GEMS are highly genetically related to isolates from blood.

When we examined the antimicrobial susceptibility of GEMS NTS isolates, we detected marked regional differences in resistance. We observed similar antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in stools of cases and asymptomatic controls at all GEMS sites except for Kenya and India. Our data suggest that antibiotic-resistant NTS are circulating in the GEMS communities. Nonsusceptible NTS strains could serve as a reservoir from which antibiotic-resistance determinants can spread horizontally to other microorganisms [37]. In Africa, the majority of Typhimurium and Enteritidis isolates were MDR, which is consistent with previous findings [20, 38]. Importantly, none of the isolates from GEMS African sites were resistant to ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone, in contrast to isolates from Asia, suggesting a difference in utilization of these antibiotics. Five (of 8) Typhi from India and Pakistan were MDR but none were extensively drug resistant, as seen in the recent typhoid fever outbreak in Hyderabad, Pakistan [39].

Antibiotics are not recommended for the treatment of NTS gastroenteritis in pediatric patients due to the predisposition for extended excretion of bacteria and relapse of infection [18, 40, 41]. However, our data suggest that children with NTS disease are being prescribed antibiotics, which may have selected for resistant bacteria. We observed high prescription rates for ciprofloxacin and other fluoroquinolones in Asia and, not surprisingly, also high resistance of Salmonella to ciprofloxacin in Asia but not Africa (where ciprofloxacin was rarely prescribed). In contrast, we recorded high antibiotic prescription rates of TMP/SMX in Africa, which possibly led to the high resistance observed in Africa. TMP/SMX in combination with highly active antiretroviral therapy has been used routinely as prophylaxis for opportunistic infections in patients with HIV in Africa [42].

The low frequency of Salmonella in MSD cases from Mali, The Gambia, and Mozambique was somewhat unexpected given that these countries report high iNTS disease burdens [3, 31, 32]. However, the incidence of iNTS disease during GEMS (2007–2010) in these 3 countries decreased relative to earlier estimates, concomitant with a reduction in clinical malaria [3, 31, 32, 43]. Indeed, there is growing evidence to suggest that iNTS disease is correlated with clinical malaria and that efforts to control malaria have resulted in reduced iNTS disease incidence [9, 44]. A re-analysis of GEMS using quantitative molecular diagnostic methods showed higher attributable fractions for Salmonella in all age groups at all sites [45].

Our findings have 3 main implications: (1) the prevalence data could be used to refine incidence estimates for individual Salmonella serovars; (2) we report for the first time the association of Typhimurium ST313 with acute diarrhea, thereby showing that these bacteria are not just associated with invasive disease; and (3) our data demonstrate widespread asymptomatic carriage of ST313, a key cause of iNTS infections. Because we found that humans are carriers of MDR Salmonella strains that also cause iNTS [46], it is possible that these individuals serve as intermediaries in transmission and maintenance of these bacteria in the community.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (grant numbers 38874, OPP1033572) to M. M. L. M. M. L. is supported in part by the Simon and Bessie Grollman Distinguished Professorship. This work was also supported by a Global Challenges Research Fund data and resources grant to the Earlham Institute (grant number BBS/OS/GC/000009D) and the Core Strategic Program of the Earlham Institute (grant number BB/CCG1720/1). Next-generation sequencing and library construction were delivered via the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council National Capability in Genomics and Single Cell at Earlham Institute (grant number BB/CCG1720/1), by members of the Genomics Pipelines Group. This project was also supported by the Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (grant number 106914/Z/15/Z) to J. C. D. H. C. V. P. is supported by a Fee Bursary award and the John Lennon Memorial Scholarship awarded by the University of Liverpool.

Potential conflicts of interest. S. M. T. and M. M. L. are co-inventors (covered by multiple patents) of a trivalent Salmonella (Enteritidis/Typhimurium/Typhi Vi) conjugate vaccine and live attenuated NTS vaccines. M. M. L. reports grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation during the conduct of the study; in addition, M. M. L. has a US patent 9 050 283, entitled “Broad Spectrum Vaccine Against Non-Typhoidal Salmonella,” issued 9 June 2015, licensed to Bharat Biotech International; a UK patent 2387417, entitled “Broad Spectrum Vaccine Against Non-Typhoidal Salmonella,” issued 11 May 2016, licensed to Bharat Biotech International; a France patent 2387417, entitled “Broad Spectrum Vaccine Against Non-Typhoidal Salmonella,” issued 11 May 2016, licensed to Bharat Biotech International; a Germany patent 2387417, entitled “Broad Spectrum Vaccine Against Non-Typhoidal Salmonella,” issued 11 May 2016, licensed to Bharat Biotech International; an India patent 312110, entitled “Broad Spectrum Vaccine Against Non-Typhoidal Salmonella,” issued 1 May 2019, licensed to Bharat Biotech International; a US patent 10 716 839, entitled “Compositions and Methods for Producing Bacterial Conjugate Vaccines,” issued 21 July 2020, licensed to Bharat Biotech International; and an India patent application 201717038528, entitled “Compositions and Methods for Producing Bacterial Conjugate Vaccines,” filed 30 October 2017, pending to Bharat Biotech International. S. M. T. reports grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation during the conduct of the study; in addition, S. M. T. has a US patent 9 050 283 licensed to Bharat Biotech for Salmonella vaccines, a US patent 9 011 871 licensed to Bharat Biotech for Salmonella vaccines, a patent for live attenuated nontransmissible Salmonella vaccine pending (application pending), and a patent for a broad-spectrum Salmonella vaccine pending (provisional patent application submitted). D. S. and A. S. G. F. report full-time employment with GSK Vaccines, after the conduct of the study. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Jones TF, Ingram LA, Cieslak PR, et al. Salmonellosis outcomes differ substantially by serotype. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardemil CV, Sherchand JB, Shrestha L, et al. Pathogen-specific burden of outpatient diarrhea in infants in Nepal: a multisite prospective case-control study. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2017; 6:e75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwambana-Adams B, Darboe S, Nabwera H, et al. Salmonella infections in The Gambia, 2005-2015. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(Suppl 4):S354–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung DT, Das SK, Malek MA, et al. Non-typhoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis at a diarrheal hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1996–2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2013; 88:661– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taniuchi M, Sobuz SU, Begum S, et al. Etiology of diarrhea in Bangladeshi infants in the first year of life analyzed using molecular methods. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:1794–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Reilly CE, Jaron P, Ochieng B, et al. Risk factors for death among children less than 5 years old hospitalized with diarrhea in rural western Kenya, 2005–2007: a cohort study. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD 2016 Diarrhoeal Disease Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1211–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA. Invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa. Lancet 2012; 379:2489–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SE, Pak GD, Aaby P, et al. The relationship between invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease, other bacterial bloodstream infections, and malaria in sub- Saharan Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62(Suppl 1):S23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iroh Tam PY, Musicha P, Kawaza K, et al. Emerging resistance to empiric antimicrobial regimens for pediatric bloodstream infections in Malawi (1998–2017). Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks F, von Kalckreuth V, Aaby P, et al. Incidence of invasive Salmonella disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicentre population-based surveillance study. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5:e310–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feasey NA, Hadfield J, Keddy KH, et al. Distinct Salmonella Enteritidis lineages associated with enterocolitis in high-income settings and invasive disease in low-income settings. Nat Genet 2016; 48:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okoro CK, Barquist L, Connor TR, et al. Signatures of adaptation in human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium ST313 populations from sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015; 9:e0003611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res 2009; 19:2279–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Achtman M, Wain J, Weill FX, et al. ; S. Enterica MLST Study Group . Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1002776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molly Freeman HK, Tasimwa H, Van Duyne S, Caidi H, Lauer A, Mikoleit M. Characterization of Salmonella isolates from invasive infections collected during acute febrile illness (AFI) surveillance in Uganda from 2016–2018 [a bstract 37]. In: Abstracts of the 11th International Conference on Typhoid and Other Invasive Salmonelloses (Hanoi, Vietnam). Washington, DC: Sabin Vaccine Institute, 2019.

- 17.Akullian A, Montgomery JM, John-Stewart G, et al. Multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella associated with invasive disease in western Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossier P, Urfer E, Burnens A, et al. Clinical features and analysis of the duration of colonisation during an outbreak of Salmonella braenderup gastroenteritis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000; 130:1185–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onwuezobe IA, Oshun PO, Odigwe CC. Antimicrobials for treating symptomatic non-typhoidal Salmonella infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 11:CD001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kariuki S, Revathi G, Kariuki N, et al. Invasive multidrug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in Africa: zoonotic or anthroponotic transmission? J Med Microbiol 2006; 55:585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kariuki S, Gordon MA, Feasey N, Parry CM. Antimicrobial resistance and management of invasive Salmonella disease. Vaccine 2015; 33(Suppl 3):C21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013; 382:209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotloff KL, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, et al. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(Suppl 4):S232–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panchalingam S, Antonio M, Hossain A, et al. Diagnostic microbiologic methods in the GEMS-1 case/control study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(Suppl 4):S294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy H, Diallo S, Tennant SM, et al. PCR method to identify Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi, Paratyphi A, and Paratyphi B among Salmonella isolates from the blood of patients with clinical enteric fever. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:1861–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tennant SM, Diallo S, Levy H, et al. Identification by PCR of non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars associated with invasive infections among febrile patients in Mali. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4:e621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blackwelder WC, Biswas K, Wu Y, et al. Statistical methods in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(Suppl 4):S246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR, et al. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet 2012; 44:1215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine MM, Robins-Browne RM. Factors that explain excretion of enteric pathogens by persons without diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(Suppl 4):S303–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mølbak K, Wested N, Højlyng N, et al. The etiology of early childhood diarrhea: a community study from Guinea-Bissau. J Infect Dis 1994; 169:581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandomando I, Bassat Q, Sigauque B, et al. Invasive Salmonella infections among children from rural Mozambique, 2001–2014. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(Suppl 4):S339–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tapia MD, Tennant SM, Bornstein K, et al. Invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella infections among children in Mali, 2002–2014: microbiological and epidemiologic features guide vaccine development. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(Suppl 4):S332–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breurec S, Reynaud Y, Frank T, et al. Serotype distribution and antimicrobial resistance of human Salmonella enterica in Bangui, Central African Republic, from 2004 to 2013. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019; 13:e0007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phoba MF, Barbé B, Ley B, et al. High genetic similarity between non-typhoidal Salmonella isolated from paired blood and stool samples of children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14:e0008377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kariuki S, Mbae C, Van Puyvelde S, et al. High relatedness of invasive multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella genotypes among patients and asymptomatic carriers in endemic informal settlements in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020; 14:e0008440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Post AS, Diallo SN, Guiraud I, et al. Supporting evidence for a human reservoir of invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella from household samples in Burkina Faso. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019; 13:e0007782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McInnes RS, McCallum GE, Lamberte LE, van Schaik W. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in the human gut microbiome. Curr Opin Microbiol 2020; 53:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordon MA, Graham SM, Walsh AL, et al. Epidemics of invasive Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium infection associated with multidrug resistance among adults and children in Malawi. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:963–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qamar FN, Yousafzai MT, Khalid M, et al. Outbreak investigation of ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and its risk factors among the general population in Hyderabad, Pakistan: a matched case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson JD, Kusmiesz H, Jackson LH, Woodman E. Treatment of Salmonella gastroenteritis with ampicillin, amoxicillin, or placebo. Pediatrics 1980; 65:1125–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stapels DAC, Hill PWS, Westermann AJ, et al. Salmonella persisters undermine host immune defenses during antibiotic treatment. Science 2018; 362:1156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crook AM, Turkova A, Musiime V, et al. ; ARROW Trial Team . Tuberculosis incidence is high in HIV-infected African children but is reduced by co-trimoxazole and time on antiretroviral therapy. BMC Med 2016; 14:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Institut National de la Statistique (INSTAT), Cellule de Planification et de Statistique Secteur Santé-Développement Social et Promotion de la Famille (CPS/SS-DS-PF) and ICF. Enquête Démographique et de Santé au Mali 2018. Bamako, Mali and Rockville, Maryland, USA: INSTAT, CPS/SS-DS-PF and ICF, 2019. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR358/FR358.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tabu C, Breiman RF, Ochieng B, et al. Differing burden and epidemiology of non-Typhi Salmonella bacteremia in rural and urban Kenya, 2006–2009. PLoS One 2012; 7:e31237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, et al. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet 2016; 388:1291–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.GBD 2017 Non-Typhoidal Salmonella Invasive Disease Collaborators. The global burden of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:1312–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.