Abstract

Objectives:

To report an unusual case of simultaneous presentation of Addison's and Graves' disease in an adolescent female previously diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and Hashimoto's.

Case presentation:

A 15-year-old female with T1D and hypothyroidism presented to the emergency department with altered mental state, fever, and left arm weakness for one day. Clinical work-up revealed coexistent new-onset adrenal insufficiency and hyperthyroidism. Her clinical course was complicated by severe, life-threating multisystem organ dysfunction including neurologic deficits, acute kidney injury, and fluid overload. Thyroidectomy was ultimately performed in the setting of persistent signs of adrenal crises and resulted in rapid clinical improvement.

Conclusions:

Endocrinopathy should be included in the differential diagnosis of altered mental status. This case additionally illustrates the challenges of managing adrenal insufficiency in the setting of hyperthyroidism and supports the use of thyroidectomy in this situation.

Keywords: autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2, adrenal insufficiency, Addison’s Disease, Graves’ disease, thyrotoxicosis

Introduction

Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2 (APS-2) is a polygenic disorder defined by the presence of two or more of the following autoimmune endocrinopathies: Addison’s disease (primary adrenal insufficiency), type 1 diabetes (T1D), and thyroid disease (hypo- or hyperthyroidism) [1]. Approximately 11% of individuals with APS-2 will have all three of these conditions, with hypothyroidism being more common than hyperthyroidism [2]. Additional autoimmune disorders may also be present. APS-2 is more prevalent in women and is most commonly diagnosed in early adulthood, although it can develop at any age [3]. Development of clinical autoimmunity can proceed in any order. Addison’s disease has been reported to be the initial disorder in approximately 50% of cases [3]. However, when one of the endocrinopathies is T1D, T1D tends to develop first [4]. Current clinical practice guidelines from the American Diabetes Association suggest that children with T1D should be screened annually for thyroid disease (by serum thyroid stimulating hormone) and every 2–5 years for celiac disease (by serum tissue transglutaminase antibodies) [5]. Routine biochemical screening for Addison’s is not recommended, owing to the low incidence of these conditions

Here we report an unusual simultaneous presentation of new-onset Addison’s and Graves’ disease in an adolescent with existing T1D and Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism. Her clinical course was complicated by severe multisystem organ dysfunction and sustained adrenal crisis that did not resolve until thyroidectomy.

Case description

A 15-year-old female with T1D and hypothyroidism presented to the emergency department with altered mental state, fever, and left arm weakness for 1 day. She developed T1D at 8 years of age and was being treated with a basal-bolus insulin regimen via pump. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values had ranged from 8.4 to 8.7% over the past 2 years, last assessed 7 months prior. Insulin doses at presentation included a basal rate of 0.55 units/h over 24 h, insulin sensitivity factor of 1:60 mg/dL, target 140 mg/dL, and carbohydrate coverage of 1:17 g. Review of outside endocrine records did not reveal any recent changes in insulin requirements. She had been treated with levothyroxine 25 mcg daily since the age of 14 years, no recent thyroid function tests were available. There was no mention of goiter, hyperpigmentation, or weight loss on past physical exams.

Physical exam upon presentation was notable for tachycardia (heart rate of 124 beats per minute), confusion, hyporeflexia, and thyromegaly. Blood pressure was 124/68 mm Hg. Initial testing included head CT and MRI (normal, performed with concern for cerebrovascular accident), EEG (abnormal, encephalopathy with frequent epileptiform discharges), EKG (abnormal, diffuse T wave inversion and prolonged QT interval with QTc 489 ms), echocardiogram (structurally normal heart, mildly decreased right ventricular function, mild mitral regurgitation). Laboratory data at admission are summarized in Table 1 and were notable for suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) with elevated free thyroxine (free T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), elevated N-terminal pro hormone brain natriuretic protein (NT-pro-BNP) and HbA1c of 8.5%. Urine toxicology screen was negative, initial electrolytes were normal with the exception of hypomagnesemia, complete blood count showed normal white blood cell concentration, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed lymphocytic pleocytosis without organisms or viral DNA.

Table 1:

Laboratory data at presentation in a 15-year-old female with altered mental status.

| Patient | Reference range | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Chemistry | ||

| Sodium, mmol/L | 139 | 133–145 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.5 | 3.6–5.2 |

| Chloride, mmol/L | 105 | 96–108 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 21 | 20–28 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 19 | 6–20 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.79 | 0.5–1 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 117 | 60–99 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 9.1 | 9–10.4 |

| Magnesium, mg/dL | 1.2 | 1.6–2.5 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 4.8 | 2.7–4.5 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.3 | 3.5–5.2 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 27 | 0–35 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 32 | 0–35 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 71 | 70–230 |

| Hematology | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.6 | 11.2–15.7 |

| Hematocrit, % | 32 | 34–45 |

| White blood cells, thou/uL | 7.8 | 4–10 |

| Platelets, thou/uL | 287 | 160–370 |

| Sedimentation rate, mm/h | 19 | 0–20 |

| Thyroid | ||

| TSH (uIU/mL) | <0.01 | 0.27–4.2 |

| Free T4, ng/dL | 3.6 | 0.9–1.7 |

| T3, ng/dL | 405 | 80–200 |

| Cardiac | ||

| NT-pro-BNP, pg/mL | 2839 | 0–450 |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | ||

| Nucleated cells, U/L | 10 | 0–7 |

| Red blood cells, U/L | 520 | 0–5 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 95 | 50–80 |

| Protein, mg/dL | 31 | 10–41 |

Italics indicate potentially clinically relevant values outside the reference range

The patient was admitted to the PICU for further care. Antithyroid therapy was initiated with propylthiouracil (PTU). Levetiracetam and empiric antibiotics were also started. Within hours of admission, she experienced recurrent hypoglycemic episodes requiring intravenous dextrose infusion. A cosyntropin stimulation test was performed with peak cortisol response <1.1 ug/dL. Random adrenocorticotropic was markedly elevated (2101 pg/mL, normal 7–63 pg/mL), consistent with primary adrenal insufficiency. Despite the initiation of stress dose steroids, the patient experienced rapid clinical deterioration including respiratory distress requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation, edema (10 kg weight gain over admission), acute kidney injury with oliguria, and low-grade fever (max 38.4 Celsius). The patient was switched from PTU to methimazole (suspected adverse reaction in setting of edema/respiratory distress), started on propranolol (to control hyperthyroid symptoms), received intermittent furosemide (diuretic, to treat edema), maintained on IV hydrocortisone at stress doses, and IV insulin infusion. Clinical status improved and she was extubated after 4 days. TSH receptor antibody and thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin were elevated, confirming Graves’ disease. All blood and CSF cultures were negative, as were viral and autoimmune encephalitis panels, immunoglobulins, and antibody testing for lupus and autoimmune vasculitis. CSF was notable for elevated glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) levels and mildly elevated oligoclonal bands.

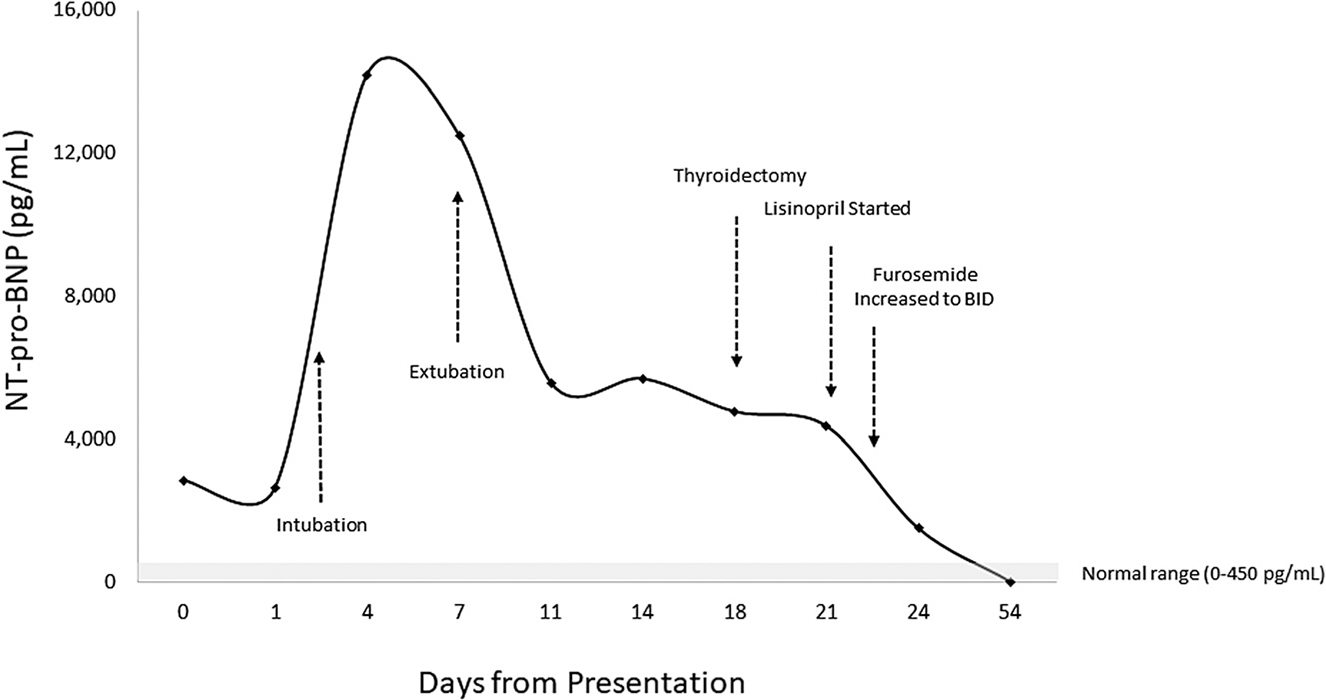

The patient’s post-ICU course was complicated by ongoing edema and volume overload requiring twice daily furosemide for diuresis and afterload reduction with lisinopril. Attempts to wean steroid replacement to maintenance doses were met with symptomatic hypoglycemia and nausea/vomiting. Serum T3 improved on therapy, but free T4 remained elevated and TSH remained suppressed (Supplemental Figure 1). Total thyroidectomy was performed 18 days after presentation. There was rapid clinical improvement postoperatively. Hydrocortisone was weaned to maintenance within three postoperative days and she was discharged within a week. Weight at discharge was down 17 kg from maximum during the hospital admission, discharge medications included hydrocortisone, fludrocortisone, insulin lispro (via pump), levothyroxine, lisinopril, magnesium oxide, and calcium carbonate. At cardiology follow-up 3 weeks postdischarge, she was found to be normotensive, with normal ventricular function on echocardiogram, an improved QTc of 461 ms, and NT-pro-BNP levels that had normalized (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

N-terminal (NT)-pro hormone brain natriuretic protein (NT-pro-BNP) was elevated at presentation, increased markedly in the setting of clinical deterioration marked by rapid onset of edema and respiratory distress, and eventually normalized after resolution of hyperthyroidism via thyroidectomy and after-load reduction via ace inhibitor and diuresis with furosemide.

Permission to publish details of this case was provided by patient and family, per the policies of the IRB of the University of Rochester Medical Center, IRB oversight and written consent/assent were not required as this report did not meet definition of human subject research.

Discussion

Simultaneous presentation of new-onset Graves’ and Addison’s disease is extremely uncommon. We could find only three previous reports of children with APS-2 presenting in this manner [6, 7]. Notably, none of these children had T1D. Our patient’s clinical course was more severe than those previously reported. Extensive investigations for other autoimmune or infectious disease did not identify any additional comorbid conditions to explain the severity of her symptoms. Furthermore, she exhibited rapid clinical improvement after thyroidectomy, suggesting that her presentation was an extreme example of the adverse multisystem effects of hyperthyroidism, confounded by adrenal insufficiency and diabetes.

An interesting aspect of this case was the dramatically elevated NT-pro-BNP levels, fluid retention, and weight gain. NT-pro-BNP is a cardiac peptide commonly used as a biomarker of heart failure. The degree of NT-pro-BNP evaluation in our patient was out of proportion to her evaluation, with only mild right ventricular systolic dysfunction seen on echocardiogram (which subsequently resolved). Acute kidney injury (AKI) and volume overload were also present, which likely contributed to the rise in NT-pro-BNP in the days following admission [8]. It is not clear what triggered the AKI or fluid overload, as these are not commonly observed features of either Graves’ or Addison’s disease. Anaphylaxis to PTU was considered, but there was no rash or laryngeal edema noted. Thyrotoxicosis may have also played a role, as individuals with hyperthyroidism have been show ntoha ve high erNT-p ro-BNPleve lscomp aredto t hose with normal or low thyroid function, although the mechanism is not known [9]. Ultimately, the combination of thyroidectomy, afterload reduction with ace-inhibitor therapy, and diuresis resulted in complete normalization of NT-pro-BNP levels within a few weeks.

Another notable aspect of her course was the altered mental status and focal neurologic deficit at presentation. Disorientation and encephalopathy were also present in one of the prior reports of thyrotoxicosis and Addison’s disease, but no cause was ever determined [6]. Encephalopathy and seizures have been reported in association with thyroid storm, although the mechanistic pathway is unknown [10]. In the setting of T1D and Addison’s, it is also possible that the patient had an unrecognized severe hypoglycemic event preceding hospital presentation. Finally, CSF analysis revealed elevated GAD antibody levels (also elevated in serum), which have been associated with a variety of neurologic disorders [11]. However, the clinical significance of elevated GAD antibodies in the CSF of people with T1D is not clear. Also surprising was the lack of abnormalities in sodium and potassium levels at presentation, given the degree of ACTH elevation. Intracellular shifting of potassium in the setting of thyrotoxicosis has been described [12]; however, the relative magnitude of this shift relative to the expected rise of serum potassium in association with mineralocorticoid deficiency is not known.

There was debate among clinical providers as to whether our patient’s presentation was consistent with thyroid storm. Thyroid storm is a life-threatening condition resulting from severe thyrotoxicosis that can lead to multiple organ failure [13]. Diagnostic criteria vary due to the range of clinical manifestations, especially within the pediatric population. The Burch–Wartofsky Scale is commonly used to identify thyroid storm in adults. This tool assigns point values based upon the severity of clinical manifestations including fever, tachycardia, congestive heart failure, central nervous system disturbance, gastrointestinal-hepatic dysfunction, and a precipitating event, with a score of >45 suggestive of thyroid storm [14]. Our patient scored 50, with half of the points coming from her neurologic and cardiac status. Adjuvant therapies for thyroid storm, including iodine and high-dose glucocorticoids, were considered, but were not administered based upon findings of only mild hypertension and tachycardia. It is possible that the untreated adrenal insufficiency at presentation may have been masking the more classic features of thyrotoxicosis (severe tachycardia and hypertension).

We attribute her inability to wean from stress dose to maintenance steroids to inadequately controlled hyperthyroidism. Hyperthyroidism increases the metabolism of corticosteroids and can lead to adrenal crisis [15]. Rapid resolution of the hypoglycemia and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency postthyroidectomy in our patient appear to support the contributory role of thyroid hormone excess. In contrast to our patient, the previous reported cases of new-onset Graves’ and Addison’s disease recovered with medical management alone. We suspect that the additional presence of insulin-dependent diabetes, a complicating factor in our patient’s case, contributed to the hypoglycemic episodes that occurred with steroid dose reductions.

Supplementary Material

What is new?

Our case illustrates that early thyroidectomy may be beneficial in patients with thyrotoxicosis accompanied by adrenal crisis and multisystem organ dysfunction.

Aggressive medical management with an ace inhibitor and loop diuretic was additionally required to treat severe volume overload accompanied by elevated N-terminal pro hormone brain natriuretic protein levels, a rare complication of thyrotoxicosis.

Learning points.

Endocrinopathy including hyperthyroidism and adrenal insufficiency should be included in the differential diagnosis of the child presenting with altered mental status.

Thyroidectomy may be superior to antithyroid medical management in medically complex cases of thyrotoxicosis accompanied by adrenal insufficiency and multisystem organ dysfunction.

Fluid overload accompanied by elevated NT-pro-BNP is a rare complication of thyrotoxicosis that may require aggressive medical management to promote diuresis and reduce cardiac afterload.

Research funding:

DRW was supported by National Institutes of Health DK114477, BG by the Strong Children’s Research Center at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The funding organizations played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Supplementary Material: Biochemical response of thyroid function tests to antithyroid medications. Propylthiouracil was initiated on hospital day 1 at a dose of 50 mg every 8 h, increased to 100 mg every 8 h on hospital day 2, and changed to methimazole 20 mg every 6 h on hospital day 3 due to concern for anaphylaxis. Reference ranges in the University of Rochester lab for triiodothyronine (T3, 80–200 ng/dL) and free thyroxine (Free T4, 0.9–1.7 ng/dL) are shown bounded by dashed and solid lines, respectively.

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/jpem-2020-0438).

Contributor Information

Bethany Graulich, Department of Pediatrics, Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester NY, USA.

Krystal Irizarry, Department of Pediatrics, Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester NY, USA.

Craig Orlowski, Department of Pediatrics, Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester NY, USA.

Carol A. Wittlieb-Weber, Department of Pediatrics, Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester NY, USA

David R. Weber, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Roberts Center for Pediatric Research, 2716 South Street, 19146, Philadelphia, PA, USA, and Department of Pediatrics, Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester NY, USA.

References

- 1.Husebye ES, Anderson MS, Kampe O. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1132–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van den Driessche A, Eenkhoorn V, Van Gaal L, De Block C. Type 1 diabetes and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome: a clinical review. Neth J Med 2009;67:376–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schatz DA, Winter WE. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome. II: Clinical syndrome and treatment. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 2002;31:339–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chantzichristos D, Persson A, Eliasson B, Miftaraj M, Franzén S, Svensson AM, et al. Incidence, prevalence and seasonal onset variation of Addison’s disease among persons with type 1 diabetes mellitus: nationwide, matched cohort studies. Eur J Endocrinol 2018;178:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. 13. Children and adolescents: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020; 43:S163–s82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell GA, Coulter JB, Isherwood DM, Diver MJ, Smith DS. Autoimmune Addison’s disease and thyrotoxic thyroiditis presenting as encephalopathy in twins. Arch Dis Child 1991;66: 350–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz L, Hammer E. Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type II with co-manifestation of Addison’s and Graves’ disease in a 15-year-old boy: case report and literature review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2020;33:575–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law C, Glover C, Benson K, Guglin M. Extremely high brain natriuretic peptide does not reflect the severity of heart failure. Congest Heart Fail 2010;16:221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pakula D, Marek B, Kajdaniuk D, Krysiak R, Kos-Kudla B, Pakula P, et al. Plasma levels of NT-pro-brain natriuretic peptide in patients with overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Endokrynol Pol 2011;62:523–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HS, Hwang JS. Seizure and encephalopathy associated with thyroid storm in children. J Child Neurol 2011;26:526–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baizabal-Carvallo JF. The neurological syndromes associated with glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies. J Autoimmun 2019;101: 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam L, Nair RJ, Tingle L. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis. SAVE Proc 2006;19:126–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh T, Isozaki O, Suzuki A, Wakino S, Iburi T, Tsuboi K, et al. Guidelines for the management of thyroid storm from the Japan thyroid association and Japan endocrine society (First edition). Endocr J 2016;63:1025–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burch HB, Wartofsky L. Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 1993;22:263–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer G, Badenhoop K, Linder R. Addison’s disease with polyglandular autoimmunity carries a more than 2.5-fold risk for adrenal crises: German Health insurance data 2010–2013. Clin Endocrinol 2016;85:347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.