Abstract

Objective

To explore the evidence on nurses’ experiences and preferences around shift patterns in the international literature.

Data sources

Electronic databases (CINHAL, MEDLINE and Scopus) were searched to identify primary studies up to April 2021.

Methods

Papers reporting qualitative or quantitative studies exploring the subjective experience and/or preferences of nurses around shift patterns were considered, with no restrictions on methods, date or setting. Key study features were extracted including setting, design and results. Findings were organised thematically by key features of shift work.

Results

30 relevant papers were published between 1993 and 2021. They contained mostly qualitative studies where nurses reflected on their experience and preferences around shift patterns. The studies reported on three major aspects of shift work: shift work per se (i.e. the mere fact of working shift), shift length, and time of shift. Across all three aspects of shift work, nurses strive to deliver high quality of care despite facing intense working conditions, experiencing physical and mental fatigue or exhaustion. Preference for or adaptation to a specific shift pattern is facilitated when nurses are consulted before its implementation or have a certain autonomy to self-roster. Days off work tend to mitigate the adverse effects of working (short, long, early or night) shifts. How shift work and patterns impact on experiences and preferences seems to also vary according to nurses’ personal characteristics and circumstances (e.g. age, caring responsibilities, years of experience).

Conclusions

Shift patterns are often organised in ways that are detrimental to nurses’ health and wellbeing, their job performance, and the patient care they provide. Further research should explore the extent to which nurses’ preferences are considered when choosing or being imposed shift work patterns. Research should also strive to better describe and address the constraints nurses face when it comes to choice around shift patterns.

Introduction

Shift work is an established feature of working life for many hospital nurses, who work to provide 24-hour healthcare. Several directives and regulations influence how shift work is organised, including the European Working Time Directive of 2003 [1] and the US Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 [2]. Such directives limits the maximum number of weekly hours or regulate the frequency of work breaks. Notwithstanding such regulations, shift work can be organised in a variety of ways, in terms of shift length, overtime, weekly hours, rotating and/or permanent schedules. How shift patterns are organised play a key role in factors influencing nurses’ wellbeing and performance, as well as patient outcomes and health systems’ productivity [3].

For instance, shift work may require nurses to work overnight causing adverse health effects, such as increased sleepiness at the end of the shift [4] or disturbed sleep [5]. Shift work schedules can also have unintended consequences depending on whether they are rotating or permanent. Working permanent night shifts is associated with higher long-term sickness absence rates in comparison to day-shifts only [6]. In the same vein, working as part of a rotating schedule is associated with increased levels of acute fatigue [7], errors [8] and higher risks of alcohol consumption [9]. These factors can in turn jeopardise the quality of care.

While a three-shift pattern with two 8-hour day shifts and a night shift remains common, long shifts of 12 hours or more as part of a two-shift system have become standard in many countries including Ireland, Poland, the USA and increasingly in the UK [10, 11]. Despite a number of claims that a two-shift system is more efficient, there is no evidence of productivity gain when working long shifts [12] and job dissatisfaction is higher among nurses working long shifts [11, 13, 14]. Working long shifts is also associated with nurses reporting reduced educational opportunities, fewer opportunities to discuss patient care [15], increased delayed or missed care [16] and higher (pneumonia) mortality rates [17] in comparison to shorter shifts. Nurses working long shifts are also more likely to experience burnout and report intention to leave in comparison to their counterparts [13, 14].

Despite such adverse outcomes, some literature suggest certain nurses prefer working long shifts, as evidenced by their higher job and schedule satisfaction, as well as their lower emotional exhaustion level [18]. Preference for long shifts is also attributed to improved work-life balance [19], higher number of days off and opportunities for greater continuity of care [20]. However, the mechanisms explaining such preferences, how nurses experience these shift patterns, and how these shift patterns interact with other aspects of their life remains unclear.

The evidence on nurses’ subjective experience and preferences around shift patterns has not been summarised, as quantitative studies reporting associations dominate the field. In these studies, adverse experiences are indirectly inferred from (for example) reported associations between shift patterns and burnout. The purpose of such quantitative studies is generally not to capture nurses’ perspectives. Yet, insights from nurses’ perspective are key to better understand mechanisms of preference and choice around shift patterns. Studies where nurses’ perspectives are directly obtained (rather than inferred by the researcher) could shed further light on the contradictions arising from the quantitative body of evidence. Nursing staff form the largest group in the health workforce, and comprehending their experience and preferences around shift patterns is key to effectively improve nursing working conditions, enhance nurses’ job satisfaction and increase quality of care. This review focusses only on nurses because the experience of shift work is specific to the occupation and the context specific [21]. Therefore, the aim of this review is to examine and summarise the extent, range and nature of research activity on nurses’ subjective experience and preferences around shift patterns.

Methods

Because of our broad research question, we conducted a scoping review [22, 23], aiming to summarise existing evidence and highlight gaps.

Search and inclusion/exclusion strategy

We searched CINAHL, Medline and Scopus with terms pertaining to nurses’ experience and preferences around shift patterns. Searches were undertaken up to April 2021. Table 1 provides a detailed list of the key terms that we used for the search. We limited our search to studies with an English language abstract. There was no restriction on the publication date to ensure the review of research was comprehensive.

Table 1. Search strategy for scoping review on nurses’ experience and preferences around shift pattern.

| CINHAL (EBSCO) (N = 1,225) |

| S1 shift work |

| S2 work schedule |

| S3 shift pattern |

| S4 shift length |

| S5 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 |

| S6 “nurse” |

| S7 health professionals |

| S8 S6 OR S7 |

| S9 S5 AND S8 |

| S10 “impact” |

| S11 “effect” |

| S12 “affect” |

| S13 “perception” |

| S14 “experience” |

| S15 “reaction” |

| S16 “prefer*” |

| S17 S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 |

| S18 S9 AND S17 Limiters: English |

| S19 S9 AND S16 Limiters: English—Research Article |

| Medline (Ovid) (N = 1,054) |

| 1. (shift adj4 work*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 2. work* schedule.mp. |

| 3. shift pattern*.mp. |

| 4. shift length.mp. |

| 5. "Personnel Staffing and Scheduling"/ |

| 6. (shift or schedule).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

| 7. 5 and 6 |

| 8. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 7 |

| 9. nurse*.mp. |

| 10. health professional.mp. |

| 11. 9 or 10 |

| 12. impact.mp. |

| 13. effect.mp. |

| 14. affect.mp. or Affect/ |

| 15. perception.mp. or Perception/ |

| 16. experience.mp. |

| 17. reaction*.mp. |

| 18. preference.mp. |

| 19. 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 |

| 20. 8 and 11 and 19 |

| 21. 20 and “Journal Article” [Publication Type] |

| Scopus (Elsevier) (N = 1,127) |

| ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“shift work”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“work schedule”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“shift pattern”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“shift length”))) AND ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“nurse”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“health professional”))) AND ((TITLE-ABS-KEY (“impact”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“effect”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“affect”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“perception”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“experience”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“reaction”)) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“prefer*”))) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, "English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, "ar”)) |

Because we were interested in nurses’ experience and preferences around shift patterns from their perspective, we only included papers that contained explicit comments or views as reported by nursing staff, whilst excluding papers that made indirect inferences. Papers that were not specific to nursing, as well as news articles and opinions were excluded from the scoping review.

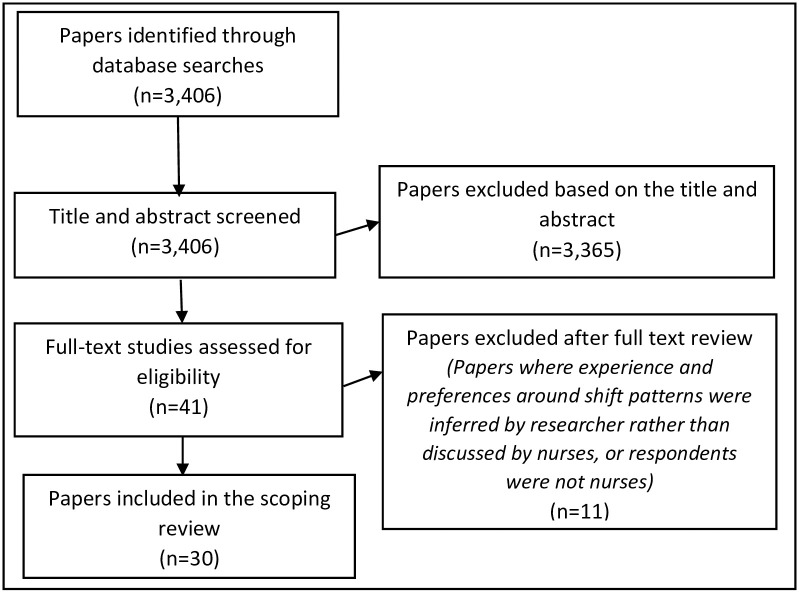

OE applied the inclusion/exclusion criteria to screen all titles and abstracts, after which CDO and PG reviewed the selections. All authors agreed that the sample of articles selected for full-text review were relevant for the research question. OE extracted data from relevant studies and met regularly with CDO and PE to discuss findings. It was during these meetings that the key concepts were discussed and refined. Any uncertainties about inclusions and exclusions were also discussed between OE, CDO and PG. The Prisma flow diagram describes the literature search and screening process in details (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Prisma flow diagram of the literature search and screening process for the scoping review on nurses’ experience and preferences around shift patterns.

Analysis

To understand the landscape of the literature, we extracted publication date, respondents’ roles (i.e. registered vs unregistered nurse), working place and shift characteristics for each study. Using Excel®, we tabulated a spreadsheet where results were recorded and organised by themes based on the authors’ findings. Using an iteration process by re-reading and analysing our results, we separated results based on the advantages and disadvantages of various shift patterns. Results reported on three core aspects of shift work, namely shift work per se, shift length and time of shift.

Results

Firstly, we provide a description of our literature findings based on the number of articles published by date, geographic setting, clinical setting, research methodology and type/length of shift. Secondly, we use a narrative to synthetize the results of the scoping review based on the three aspects of shift work that emerged from the review.

Numerical analyses of included studies

Three thousand four hundred and six (N = 3,406) records were retrieved from the database searches (Fig 1). 30 papers published between 1993 and 2021 were judged eligible. Half of the papers (n = 16) were published between 2018 and 2021. The largest group of papers came from the USA (n = 8). The UK (n = 7) and Australia (n = 6) had the second highest output. Other papers came from Asia (Iran, n = 2, China, n = 1, India, n = 1 and Cambodia, n = 1), other European countries (one each from Germany, Norway and Sweden respectively) and Canada (n = 1).

Most studies were undertaken with staff working in Acute Hospital wards (n = 27), 2 studies took place in Acute Mental Health Trusts and one study used staff from multiple settings (i.e. Acute Hospitals, Community Trusts and Care Home). The majority of papers included only registered nurses (RNs) (n = 23), whilst other papers included other nursing staff (healthcare assistant and other staff, n = 2, nursing assistant, n = 2, midwives, n = 1 and student nurse, n = 1). One paper focussed solely on unregistered healthcare staff (n = 1). The number of participants ranged between 10 [24] and 1355 [25], with female participants representing the majority of the sample.

Fifteen papers used semi-structured interviews. Four papers used questionnaire with open-ended questions and another four papers used qualitative interviews. Two papers used mixed-methods with a qualitative component and five papers used focus groups. Each paper included a discussion about nurses’ experiences and preferences around shift work from their perspective.

Overview of themes

The studies we found reported on three aspects of shift work: namely (i) shift work per se (e.g. the mere fact of working shift without referring to its length or time), (ii) shift length, and (iii) time of shift, referring to when shifts were occurring (i.e. morning, evening, or night); and, in some cases, whether these shifts were worked as part of a rotating or fixed schedule.

Discussions on shift work per se were never the focus of a whole study. Rather, nurses were in certain case describing the impact of shift work on their work or life without referring to the length or time. This concerns more than half of the studies (n = 18). When we consider the length of shift, studies focussing on long (12+ hour) shifts were more common (n = 8, including one study investigating 24-hour shifts, Koy, Yunibhand [26]). Seven studies compared 12 hour shifts with other lengths of shift, such as 4, 8 or 10 hours. In these studies, discussion and results were mainly focussed on 12 hours shifts, however. Studies focussing specifically on nurses working short shifts were less common (n = 2).

The third aspect of shift work describes shifts based on their occurrence during the day (n = 11), including studies with night shifts as sole focus (n = 9). The remaining studies (n = 4) described shifts as follows. Epstein, Söderström [27] used a basic shift description, such as ‘morning and evening’ or ‘morning, evening and night’. Gifkins, Loudoun [28] referred to nursing schedule as shift including ‘late night’ or ‘overnight work’. de Cordova, Phibbs [29] used the terminology off-shift (night and weekend), whilst Bauer [30] simply mentioned ‘early shift’ (6 to 7 am start) without indicating the overall number of hours of the shift worked. Table 2 provides a summary of all studies included in the scoping review.

Table 2. Papers included in the scoping review (arranged by aspect of shift and descending chronological order).

| Shift aspect & patterns | Author(s) and date | Country of origin | Role | Setting | Sample size | Aims of study | Methods | Theme(s) | Aspect of shift(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift length: 24 hours | Koy, V., et al. (2020) | Cambodia | RNs | Hospital | 30 | To explore the perception and experiences of 30 ICU RNs regarding their working 24h shifts | Focus groups |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 17 | |||||||||

| Male = 13 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | Suter, J. and T. Kowalski (2020) | England | RNs and HCAs | Acute mental health trust | 70 | To examine the impact of extended shifts on employee strain in a large mental healthcare organisation | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 54 | |||||||||

| Male = 16 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | Suter, J., et al. (2020) | England | RNs, HCA & managers | Acute mental health trust | 70 | To evaluate how employees in acute mental health settings adapt and respond to a new 12h shift system from a wellbeing perspective | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift length |

| Female = 54 | |||||||||

| Male = 16 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | Ose, S. O., et al. (2019) | Norway | RNs | Hospital | 24 | To record the experiences of 24 nurses working 12h shifts | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 24 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | Webster, J., et al. (2019) | Australia | RNs | Hospital | 266 | To investigate the effect on nurses and patients of 8h rostering compared with 12h rostering among 266 RNs | Questionnaire with open-ended questions |

|

Shift length |

| Female = 209 | |||||||||

| Male = 57 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | Parkinson, J., et al. (2018) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 30 | To explore the perceptions of rehabilitation nurses who are working in or who have worked 12h shifts in an acute rehabilitation hospital and to identify the advantages and disadvantages of 12h shifts | Mixed-method study with qualitative questions |

|

Shift length |

| Female = 27 | |||||||||

| Male = 3 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | Thomson, L., et al. (2017) | England | Unregistered healthcare staff | Hospital, Community trusts, Care homes | 25 | To explore unregistered healthcare staff’s perceptions of 12h shifts on work performance and patient care | Focus groups |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Shift length: 12 hours | McGettrick, K. S. and M. A. O’Neill (2006) | Scotland | RNs | Hospital | 54 | To elicit critical care nurses’ perceptions of working 12h shifts | Focus group |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 50 | |||||||||

| Male = 4 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 4 or 8, 8 and 12 | Gao, X., et al. (2020) | China | RNs | Hospital | 14 | To explore 14 nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns while providing front-line care for COVID-19 patients in isolation wards of hospitals in Shanghai and Wuhan | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 12 | |||||||||

| Male = 1 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8, 10 and 12 hours | Haller, T., et al. (2020) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 190 | To explore clinical nurses’ perspectives of shift length among 190 clinical nurses | Questionnaire with open-ended questions |

|

Shift length |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Shift length: 10 and 12 hours | Horton Dias, C. and R. M. Dawson (2020) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 21 | To explore hospital shift nurses’ experiences and perceptions of influences on making healthy nutritional choices while at work | Semi-structure interviews |

|

Shift length |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8 and 12 hours | Baillie, L. and N. Thomas (2019) | England | RNs and NAs | Hospital | 22 | To investigate how nursing care is organised on wards where nursing staff work different lengths of day shifts, and how length of day shift affects the staffing of wards | Qualitative interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8 and 12 hours | Haller, T. M., et al. (2018) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 87 | To explore clinical nurses’ perceptions of 12h shifts versus traditional 8h shifts | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8 and 10 hours | Centofanti, S., et al. (2018) | Australia | RNs and midwives | Hospital | 22 | To investigate the way nurses and midwives utilised napping and caffeine countermeasures to cope with shift work, and associated sleep, physical health, and psychological health outcomes among 130 shift-working nurses and midwives | Qualitative interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 19 | |||||||||

| Male = 3 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8 and 12 hours | Baillie, L. and N. Thomas (2017) | England | RNs and NAs | Hospital | 22 | To explore how length of day shift affects patient care and quality of communication between nursing staff and patients/families in older people’s wards | Mixed-method study with qualitative questions |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8 hours | Rathore, H., et al. (2012) | India | RNs | Hospital | 60 | To have an insight into the problems faced by female nurses in shift work | Qualitative interviews |

|

Shift work per se Shift length |

| Female = 60 | |||||||||

| Shift length: 8 and 12 hours | Reid, N., et al. (1994) | England | Student nurse | Hospital | 47 | To report on the attitudes of nurse educators and students to the 12-hour shift and their views on the impact such a shift has on nursing education among students registered general/mental nurse | Qualitative interviews |

|

Shift length |

| Female = 46 | |||||||||

| Male = 1 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Landis, T. T., et al. (2021) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 16 | To describe and interpret the lived experience of hospital night shift nurses taking breaks and the meaning of this phenomenon as it relates to the workplace. | Semi-strucured interviews |

|

Time of shift |

| Female = 14 | |||||||||

| Male = 2 | |||||||||

| Tine of shift: Morning, evening and night | Epstein, M., et al. (2020) | Sweden | RNs | Hospital | 11 | To explore newly graduated nurses’ strategies for, and experiences of, sleep problems and fatigue when starting shift-work | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 10 | |||||||||

| Male = 1 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Smith, A., et al. (2020) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 39 | To elicit night shift nurses’ perceptions of drowsy driving, countermeasures, and educational and technological interventions. | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Time of shift |

| Female = 26 | |||||||||

| Male = 13 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Matheson, A., et al. (2019) | Australia | RNs | Hospital | 10 | To explore women’s experiences of working shift work in nursing whilst caring for children | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 10 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Books, C., et al. (2017) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 101 | To study night shift work and its health effects on nurses | Questionnaire with open-ended questions |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 88 | |||||||||

| Male = 13 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Shifts including late night and overnight work | Gifkins, J., et al. (2017) | Australia | RNs | Hospital | 21 | To compare perceptions of nurses exposed to short- or longer-term shift work and their experiences working under this type of scheduling | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 21 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | West, S., et al. (2016) | Australia | RNs | Hospital | 1355 | To develop a conceptual model of nurse-identified effects of night work among 1355-night working RNs employed in a state/public health system | Questionnaire with open-ended questions |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 115 | |||||||||

| Male = 192 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Off-shift (night and weekend) | de Cordova, P. B., et al. (2013) | USA | RNs | Hospital | 23 | To qualitatively explore 23 RNs perceptions of off-shift nursing care and quality compared with regular hours | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Time of shift |

| Female = 20 | |||||||||

| Male = 3 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Faseleh Jahromi, M., et al. (2013) | Iran | RNs | Hospital | 20 | To describe 20 Iran novice nurses’ perception of working night shifts | Focus groups |

|

Time of shift |

| Female = nr | |||||||||

| Male = nr | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Powell, I. (2013) | Australia | RNs | Hospital | 14 | To report a study that explored the experiences of night-shift among 14 nurses, focusing on employee interrelationships and work satisfaction. | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Time of shift |

| Female = 14 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Fallis, W. M., et al. (2011) | Canada | RNs | Hospital | 13 | To explore nurses’ perceptions, experiences, barriers, and safety issues related to napping/not napping during night shift | Focus groups |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 11 | |||||||||

| Male = 2 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Night shift | Nasrabadi, A. N., et al. (2009) | Iran | RNs | Hospital | 18** | To describe the perceptions held by Iranian registered nurses (IRNs) concerning their night shift work experiences | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Shift work per se Time of shift |

| Female = 11 | |||||||||

| Male = 5 | |||||||||

| Time of shift: Early shift (6 to 7am) | Bauer, I. (1993) | Germany | RNs | Hospital | 14 | To explore perception of German nurses of early shift | Semi-structured interviews |

|

Time of shift |

| Female = 13 | |||||||||

| Male = 1 |

HCA = Health Care Assistant NA = Nursing Assistant nr = not reported

**As reported by the authors

Findings from the review are summarised and presented according to these three aspects of shift work, namely shift work per se, shift length, and time of shift. Within each aspect of shift work the impacts of shift pattern on experience and preferences are discussed.

Shift work per se

An aspect discussed by nurses when reflecting on shift patterns was shift work per se, meaning the mere fact of working shifts as opposed to a regular “9 to 5” day job.

Nurses often reported detrimental mental and physical health as a result of working shifts, as well as failure to adopt healthy strategies, such as walking or exercising when working shifts [31]. Working shifts could also act as a barrier to healthy eating with nurses reporting unhealthy eating practices [32, 33], such as overconsumption of caffeine and energy drinks, resulting in poor sleep and health outcomes [34]. Such habits could stem from different sources, including exhaustion and job-related stress which further exacerbated circadian rhythm disruption [33]. Notwithstanding the negative effect of shift work on nurses’ health and wellbeing, presenteeism (i.e. going to work when being sick resulting in lower engagement and productivity) was often brought up, in particular by nurses who are mothers. They reported feeling guilty about calling in sick, because staff shortages would mean that their shift would have to be covered by a colleague forced to do overtime [24]. This was amplified by nurses experiencing increased workload as a result of staff shortages during their shifts [25, 26, 35, 36].

Nurses asserted that working shifts could in certain cases not be conducive for rest and napping [34] or restricting access to planned break periods [37–39]. Fatigue was often discussed in relation to shift work, and it was found to be exacerbated by working more than two consecutive long shifts [37, 40]. Noticeably, nurses observed that the reduction in consecutive shifts decreased work absence [38]. Fatigue could be manifested by physical pain [41], difficulty to transition from day to night-time (and vice-versa) [42], reduced concentration [27, 37], difficulty in taking decisions or emotional manifestation, such as being easily annoyed or unengaged during shift [27].

One study revealed that preference for shift work varied depending on the length of time (i.e. experience) in working shift [28]. Experienced nurses (i.e. at least three years of shift work experience) had a preference for shift work because it aided in their work-life balance. They benefited from the support of their family, friends and senior nurses which positively impacted on their domestic and children caring responsibilities. In contrast, inexperienced nurses reported being isolated and missing out on family and social activities, because friends (more often than family) did not always understand the time constraints of working shifts [28]. The ability to request for their own roster also helped nurses to cope with shift work [28]. Relatedly, nurses choosing their own roster were more satisfied with their job [43]. In contrast, nurses were more reluctant to accept, adapt or prefer a particular shift pattern when it was mandatorily imposed [26, 37, 44].

One study by Gao et al. [35] offered a perspective on how the experience of shift work was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of the increase in patient numbers and their acuity, and, consequently in workload, nurses highlighted the need to adjust shift patterns dynamically according to the workload. They also emphasised the importance to account for nurses’ knowledge, skills and abilities during shift scheduling, as well as considering their physical and mental experience [35]. Based on their shift experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses asserted that their perspectives should be taken into consideration to humanise shift patterns. Besides, communication between managers and front-line nurses should be strengthened to understand nurse perspective when scheduling shift schedules [35].

Shift length

Nurses reflected on their experience and preferences around the length of shifts. Our review report on two main lengths of shift, short shifts (<12 hours), including 4-hours [35], 8- or 10-hour shifts; and long shifts (≥ 12 hours and more), including one study focussing on 24-hour shifts [26].

A factor discussed by nurses in relation to different shift lengths was handovers. Studies consistently highlighted how nurses believe the additional handovers resulting from shorter shifts posed a threat to safety in terms of miscommunication of patient information. One study found that nurses were concerned about the additional handover when moving from long to short shifts, such that the information did not always reach the next shifts [36]. Nurses believed the introduction of an additional handover as a result of moving to 8 hour shifts had led to a higher risk of information being miscommunicated, similar to a Chinese Whispers effect [36]. When the length of shifts was reduced from 8 to 4-hour during the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses described how they felt shorter shifts had led to more handover errors [35]. In another study, nurses reported that communication with all levels of senior staff improved, probably as a result of the extra time that long shifts offered [45]. However, not all studies concluded that long shifts were beneficial to improve communication. One study mentioned that implementing long shifts led to a disruption in communication with colleagues [38].

The loss of one handover when implementing 12 hour shifts limited opportunities for clinical education [38]. It also led to a decrease in informal social support, reduced opportunities for sharing good practices and reflection time. Nurses reported being more isolated, because core staff increasingly worked alongside agency staff which worsened collegiality [46]. In contrast, in one study, nurses reported an increased access to professional development education after 12 hour shifts were introduced. The higher rate of professional development leave was supported by organisational data [45]. One study highlighted how the ability to study was affected by the subsequent tiredness after working long shifts [47]. In some instances, the introduction of 12 hour shifts also reduced nurse confidence in their clinical skills and knowledge following extended time away from a dynamic ward environment [44, 46]. Nurses working short shifts also declared having limited access to education, teaching or staff development as a result of work intensity [36].

Nurses believed there had been an increase in staff turnover after 8 hour shifts were imposed, because staff did not like or did not adapt to the new shift pattern [36]. Some nurses feared 12 hour shifts would cause recruitment challenges of adequately trained nurses [47]. In contrast, another study reported that nurses believed 12 hour shifts would improve retention of experienced staff due to the shift flexibility and ability to increase nurses’ morale, possibly because those nurses reported a strong preference for this shift pattern [45]. Relatedly, some nurses believed the implementation of long shifts had improved staffing levels, with more nurses available during the shifts [38].

Across different studies there were contrasting results for nurses’ views about the impact of long shifts on the quality and continuity of care after 12 hour shifts were implemented. Long shifts were perceived by unregistered healthcare staff [37] and nurses to improve patient and continuity of care [38, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 49]. The implementation of long shifts rendered possible the full completion of their nursing tasks, as evidenced by fewer interruptions of work tasks and the possibility to focus on their tasks for longer [41, 42]. Nurses perceived improved communication with patients [42], as they were able to care for the same patients throughout their shifts [48]. They also reported achieving more nursing care with their patients resulting from the extra time long shifts offered [37, 41, 42].

However, in a few studies nurses reported a deterioration in the quality of care they were delivering in the last (four) hours of the shifts [47]. Nurses also had mixed views about the effect of short or long shifts on quality of care, stating their uncertainty about which shifts improved patient care [36, 40]. Nurses reported that the introduction of 12 hour shifts amplified their job strain and left some nursing tasks incomplete because of the intensity of work over an extended period of time [46]. Another study revealed that frequent changes in assignments during long shifts could negatively impact continuity of care, as nurses could not complete their nursing care with the same patients throughout their shifts [48]. The perceived increase in continuity of care over time, in the control over nursing tasks completion, and in the improved communication with patients as reasons for preferring 12 hour shifts [37, 42].

Fatigue (or tiredness) was a feature reported by nurses across all shift lengths, suggesting nurse endure a physical burden when working shifts irrespective of their length. Nursing staff working short [37, 43] and long shifts [27, 38, 40–42, 44, 47–49] reported experiencing fatigue when working shifts. Nurses reported having to pace themselves to complete their shifts, reflecting the necessity for increased physical, mental and emotional stamina when working long shifts [44, 46]. Exhaustion during and after working long shifts was also a common feature reported by nurses [26, 33, 44]. They described that working long shifts led to burnout, reduction in physical and mental health [49].

Nurses’ sleep patterns were reported to be negatively affected by both short [43] and long shifts alike [27, 33], apart for one study where nurses reported an increase in their sleep hours after moving to 12 hour shifts [45]. Some nurses working 12 hour shifts reported fatigue was more manageable since they benefited from more days off-work to recover [38, 45, 47]. In one study, some nurses recognised that fatigue was an adverse effect of long shifts, but they found this was mitigated by the increased number of days off-work [46]. The extra days off and improved work-life balance were often mentioned as the reason for a preference for long shifts [36, 38, 41, 42, 44–49]. Work-life balance was also positively rated by nurses working 8 hour shifts [49]. Noticeably, one study reported that nurses’ views of shift length on their leisure was mixed. The contrast may stem from the fact that the population of interest were student nurses, whose educational commitments may restrict their leisure time [47].

Long shifts was associated with anticipated anxiety to return to work, where nurses apprehended returning to a challenging and unpredictable workplace [44]. Stress could also stem from the changes in skill mix resulting from the implementation of 12 hour shifts. For instance, nurses’ supervision increased as a result of using extensive agency and bank staff to cover for sickness absence. Indeed, these temporary staff were unfamiliar with the ward and needed more support from substantive staff [44]. In contrast, in one study nurses felt that working long shifts reduced sickness and/or family leave, as nurses could benefit from extra days off work [45]. Nurses also reported being able to take more planned breaks when working long shifts [41, 42], albeit this was dependent on patient acuity and case mix [38].

Whilst two studies revealed nurses were satisfied or had a preference for short shifts [42, 49], more studies showed nurses preferring long shifts [37, 38, 41, 45, 47, 49]. Acceptance of 12 hour shifts was facilitated when staff were consulted prior to moving to long shifts, and, in some cases, when the request to change to 12 hour shifts came from staff themselves [41, 45, 47]. Individual characteristics and personal circumstances (e.g. age, marital status, grade or presence of children) influenced the extent to which nurses could adapt to the new shift patterns. For instance, the strain of long shifts on wellbeing was particularly intense for older nurses [25, 44, 46]. A further predictor of adaptation to 12 hour shifts was public healthcare commitment: when nursing staff were devoted to the National Health Service (NHS) and their Trust, nurses expressed they accepted the move to 12 hour shifts because they wanted to be helpful towards a struggling sector and employer [46]. Furthermore, nurses reported wanting to be seen to be coping with long shifts as a means of improving their team’s morale [46]. Nurses also reported that childcare costs were reduced when working long shifts as they allowed them to spend more days at home caring for their children [42].

Time of shift

Nurses working night shifts described how the lack of resources, for example other healthcare professionals and administrative staff, led to higher collaboration among them, higher sense of cohesion and better teamwork [25, 29], but also led to difficulty to taking their breaks [50]. Nurses working night shifts experienced increased autonomy and fewer interruptions to planned healthcare as a result of fewer family visits [25, 51]. More specifically, working night shifts allowed nurses to carry out indirect (e.g. administrative) as well as direct clinical patient care with more autonomy [25]. Relatedly, night working enabled nurses to feel more independent and more skilled, fostering their desire to continue working at night [32, 52].

However, lack of resources and of support from other professionals during the night shift led to significant concerns for nursing staff, who reported feeling not considered and appreciated by staff on day shifts [51]. Communication problems between day and night shift nurses could occur, where night nurses felt disconnected from and neglected by day nurses, and struggled to access relevant (patient) information [25]. They perceived their role as under-appreciated by other nurses [29], referring to a universal consensus that night shift nurses are perceived to be practising less or not all [51]. Some nurses experienced fear and insecurity in the last hours of their night shifts resulting from lack of resources [52], exacerbating worries around patient and professional safety [25]. Other nurses denounced inferior working conditions in comparison to their daytime counterparts, including a perception of minimal leadership [51], as well as a lack of welfare facilities [52]. Staffing levels and skill mix were also discussed in relation to night work; night shifts were often covered by temporary staff, and substantive staff felt this was a positive thing because staffing levels could be maintained [29].

Nurses working night shifts valued patient care, as evidenced by the importance they placed in knowing their patients’ conditions and care needs [51]. Nurses’ sense of duties and responsibilities firstly towards their patients also meant they could neglect taking their breaks [50]. The more ‘relaxed’ pace during weekend day shifts allowed nurses to focus more on their patients [29]. However, nurses reported that staffing levels were often inadequate at night [25] or workload was too high [51]; leading staff to report that the quality of care they delivered was negatively affected. Inexperienced nurses (less than one year nursing experience) perceived increased work pressure when working night shifts [52]. Relatedly, nurses experienced tremendous workload when working early shifts, which rendered the work unappealing altogether [30]. Nurses working off-shifts (night and weekend) also revealed they completed more tasks as a result of inadequate staffing level during these shifts [29].

Nights shifts gave rise to educational and clinical learning opportunities from which nurses benefited [25, 32, 52]. Nurses stated that night shifts were more relaxed and some e-learning not available during the day were available at night [25]. In contrast, nurses also reflected on the conundrum of night shifts where their learning opportunities were perceived as suboptimal. This was evidenced by a reduced or lack of education access in comparison to their daytime counterparts, despite added responsibility [51].

Depression, tiredness [31] and fatigue were experienced by nurses working night [25, 51, 52] and day (including evening) [27] shifts. Nurses working night shifts also experienced drowsy driving after completing their shifts [53]. Nurses adopted unhealthy strategies to combat fatigue and adapt to late or night shifts. This included caffeinated drinks and snacking on sugary foods, as well as drinking alcohol to rest and recover after night shifts [27, 28, 39]. Most common strategies to combat drowsy driving after night shifts included listening to music, talking on the phone with relatives, as well as unhealthy snacking [53]. Nurses working early shift also reported being exhausted, as evidenced by their physiological system not being used to start working so early [30].

Nurses asserted their sleep patterns were negatively affected by both early [30] and night shifts [25, 27, 31, 32, 52]. Sleep deprivation stemmed from nurses’ inability to rest between late to early shifts [30], insomnia [52], feeling sleep-deprived while working or the difficulty to achieve a normal sleep pattern after the completion of night work [25]. Nurses reported suffering from anxiety, nutritional imbalance, changed physical appearance and skin pigmentation as a result of working night shifts [32]. Early shifts also caused anticipated anxiety to return to work, with nurses finding difficult to disconnect from work and over-processing their nursing tasks while at home [30]. Stress could also results from dysfunctional organisational structures or poor workplace conditions when nurses worked night shifts [52].

Nurses worked a variety of shift work schedules (i.e. permanent or rotating) and preferences for shift patterns could vary depending on the shift work schedules they were assigned to. For instance, there is evidence nurses preferred working permanent night shifts in comparison to rotating shifts [24, 25, 31]. And there is also evidence that nurses working night shifts on a permanent basis were satisfied with this shift pattern [29]. Whilst working night shifts was exhausting, it also gave nurses a sense of fulfilment [32]. Nurses stated that the environment was more relaxed at night, as evidenced by reduced noise, fewer nursing task interruptions and increased focus-thinking time.

Nurses were able to care for their family when working late or night shifts, despite financial and non-financial constraints for single-parent families [25], or pervasive fatigue [51]. For instance, nurses working night shifts declared benefiting from shared parental responsibility and their presence at home during the day meant they avoided using after-school care [25]. However, nurses also described their sense of guilt when leaving their children to work night shifts, as well as the difficulty in co-ordinating their family and social life [24]. Working early [30] or night shifts could also result in nurses being or feeling isolated from family and friends due to unsociable working hours [25, 28, 31, 51, 52].

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first scoping review to provide a comprehensive overview of research on nurses’ experiences and preferences around shift patterns in the nursing literature. A broad range of international studies were found and included, reflecting the global interest in understanding nurses’ perspectives when reflecting on the impact of shift patterns. Findings mostly focussed on either the mere fact of working shifts, the length of shifts or the time of shift, although issues such as number of days worked in a row and ability to choose shifts also emerged. We found that all different aspects of shift work elicited a variety of positive and negative views from nursing staff, with no single shift pattern described as without limitations. In the same vein, we found that some topics or issues reported by nurses align or contrast with the corresponding quantitative evidence on nursing shifts (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparative table between subjective and quantitative evidence around nursing shift patterns.

| Theme | Quantitative evidence | Subjective experience |

|---|---|---|

| SHIFT WORK PER SE | ||

| Nurses’ health and wellbeing | ||

| SHIFT LENGTH | ||

| Nurses’ health and wellbeing |

|

|

| Patient care and workload |

|

|

| Capacity building |

|

|

| TIME OF SHIFT | ||

| Nurses’ health and wellbeing |

|

|

| Patient care |

|

|

| Workload & capacity building |

|

|

For example, exhaustion, physical and mental fatigue were outcomes reported by all nurses engaged in working shifts, regardless of their length or time of day. Quantitative research has shown that fatigue increases with the length of shift [57] and is more acute when nurses work during their days off [56]. Inter-shift fatigue (i.e. not feeling recovered from previous shift at the start of the next shift) is also prominent among nurses [4]. In our review, fatigue and exhaustion were recurring outcomes identified across all shift patterns, and they were further exacerbated by high number of consecutive shifts and the COVID-19 pandemic. Notwithstanding the frequent reports of fatigue, nurses did not seem to deploy effective coping systems. For example, studies reported how nurses resorted to unhealthy eating and drinking to survive night and/or long shifts. In addition, a number of studies highlighted how even when fatigued or ill, nurses expressed a sense of guilt towards colleagues and patients and a need to self-sacrifice, which led nurses to work when sick (i.e. presenteeism) and to miss breaks during their shifts.

This feeling of obligation towards colleagues, patients and the healthcare system is well reflected in recent studies [78] and it exemplifies the “Supernurse” culture [79], according to which nurses feel they need to sacrifice themselves, their health or their children’s health [24] for the greater good (i.e. the nursing team and/or their patients). This is a major barrier to nurses taking their breaks, calling in sick when needed and, consequently, to reducing their fatigue levels. This might be further exacerbated by the fact that the majority of nurses are women, including mothers, who feel pressured to juggle their work and childcare responsibilities [80]. Whilst fatigue was often mentioned by nurses, there was little description of their experience of fatigue. Capturing fatigue levels and its manifestation from a subjective perspective is essential, and any interventions that modify shift patterns should consider how fatigue could be impacted from the nurses’ perspective. Having enough days off to recover from shift work-related fatigue was noted in several studies. Changes and adaptations to shift patterns should consider the sequencing of days off between shifts and the cumulative number of days worked and not simply the total days off within the (arbitrary) seven day week.

We found that personal characteristics including age, length of experience, and caring responsibilities affected the experience and preferences around different shift patterns. While these were often mentioned by nurses, there was no discussion on how such personal characteristics represented a constraint for nurses when choosing or working shifts. Further research may explore the extent to which personal circumstances are constraining nurses when choosing or working shifts. Especially considering the evidence that personal circumstances are not consistently taken into account by health services when designing rotas, which are often designed based primarily on service demands rather than staff needs [46, 58, 59].

The majority of the studies included in this review were conducted in Acute Care Hospitals, indicating there is a dearth of investigation of nurses’ experiences and preferences around shift patterns in other settings. These include community and mental health hospitals. Research conducted in these areas is needed, as experiences of nurses working in those settings may differ significantly from those in acute care hospitals.

The perceived impact of shift patterns on patient care and capacity building was inconclusive, with nurses stating both negative and positive views. Some nurses reported higher continuity of care, and a lower risk of information being miscommunicated when working long shifts. In contrast, nurses in some studies felt that continuity was decreased because they were away from the ward for longer due to having more days off. Other studies found no evidence that nurses working 12 hour shifts reported improved continuity of care and less miscommunication of information compared to nurses working shorter shifts [15]. Similarly, there were contrasting views when it came to educational opportunities and shift length. Yet, an observational study found that nurses working 8 hour shifts reported having more education opportunities in comparison to those 12 hour shifts [15]. Large observational studies also show that nurses working 12 hour shifts are less likely to report high quality care or improving safety on their wards compared to those working shorter shifts [10, 68].

We found that nurses tend to prefer shift patterns when they were involved in designing those shift patterns, or, even more, when changes had been adopted based on requests from staff. Two studies captured nurses’ preferences for long shifts using a longitudinal design, enabling to elicit nurses’ preferences before, during and after the implementation of 12 hour shifts [41, 44]. Results confirmed that the mandatory imposition of changes in shift patterns [44] in contrast to a voluntary approach [41] increased the likelihood of nurses disapproval. Having choice and flexibility around shift patterns is a known predictor of increased wellbeing and health [65, 81]. Hence, interventions aimed at modifying shift patterns should consider involving nursing staff to maintain a certain degree of choice.

Our findings that many nurses prefer long shifts and believe working long shifts does not affect patient care largely contradicts the quantitative evidence, where those working long shifts are likely to report lower quality of care and job satisfaction and higher levels of burnout [10, 13, 14, 68]. Higher rates of sickness absence have also been reported for nurses working 12 hour shifts [63]. This contrast between qualitative and quantitative evidence needs further exploring; specifically, further research is required to better understand the mechanisms that lead nurses to prefer some shifts, for example whether a higher degree of choice around shift patterns is a consistent moderating factor for the negative outcomes of long shifts for either staff or patients. Previous research does not seem to indicate this [82], but a deeper investigation including triangulation of roster data and qualitative reports might shed more light.

The evidence from large observational studies does not directly link individual preferences for shifts with patient and care outcomes [62, 83], but it could be that nurses exercise choice for shift patterns that lead to less favourable working conditions because of external considerations, such as childcare. The need to accommodate responsibilities such as childcare might explain why nurses could sacrifice job satisfaction in order to balance demands. This could explain some of the apparent contradiction between these two bodies of research, such that nurses could prefer particular shifts despite the association with occupational burnout and decreased job satisfaction. Indeed, the staff themselves may not make the direct attribution even if their shift patterns played a causal role.

Whilst the scoping review has shed some light on nurses’ experiences and preferences around shift patterns, our study is not without limits. Following the scoping review process, we did not conduct a systematic appraisal of the qualities of studies [22]. Whilst this approach widens the scope of studies included in the review, it may also bias the conclusion of our findings as the strength of the evidence is not being assessed. Noticeably, we also found that most studies come from the USA, UK and Australia, and these findings might not apply to nurses working in other parts of the world. As expected in qualitative research, the sample size may appear small, but since generalisability was not the focus of our work, the themes identified in our work are still a valuable starting point that merits further investigation. However, the scoping review provides an overview of the topic under consideration, including the gaps in the literature.

Conclusion

Across all shift patterns, nurses describe how they strive to deliver high quality of care and resort to various mechanisms to cope with an ever-changing and demanding work environment. From the current literature, it is evident that shift patterns are often organised in ways that are detrimental to nurses’ health and wellbeing, to their job performance, and consequently, to the patient care they provide. Our findings highlight a number of factors that may be important in influencing nurses’ choice of shift patterns and the resulting outcomes for quality of care and the staff themselves.

While important issues such as individual differences, accommodating preferences and the need to manage fatigue are highlighted by these findings, it is not clear how best to organise shifts. The mixed findings on experience and preference for both long shifts and night work are in contrast with observational studies that show long shifts to be associated with adverse outcomes. Further research should explore the extent to which nurses’ preferences are considered when choosing or being imposed shift work patterns. Research should also strive to better describe and address the constraints nurses face when it comes to choice around shift patterns, including childcare or any other caring responsibilities, as well as individual factors such as age, with the aim to consider these constraints when restructuring shift patterns.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data (i.e. references used for the scoping review) are within the manuscript with the corresponding URL or DOI.

Funding Statement

PG received funding from NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Wessex; https://www.arc-wx.nihr.ac.uk/research-areas/workforce-and-health-systems/nursing-shift-patterns-in-acute-community-and-mental-health-hospital-wards/ The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.European Commission. Working Conditions—Working Time Directive 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=706&langId=en&intPageId=205.

- 2.U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division. Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. 2011. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/FairLaborStandAct.pdf

- 3.Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2016;57:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiger-Brown J, Rogers VE, Trinkoff AM, Kane RL, Bausell RB, Scharf SM. Sleep, sleepiness, fatigue, and performance of 12-hour-shift nurses. Chronobiology International. 2012;29(2):211–9. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.645752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kecklund G, Axelsson J. Health consequences of shift work and insufficient sleep. BMJ. 2016;355:i5210. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Redfern OC, Griffiths P. Night work for hospital nurses and sickness absence: a retrospective study using electronic rostering systems. Chronobiology International. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1806290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han K, Trinkoff AM, Geiger-Brown J. Factors associated with work-related fatigue and recovery in hospital nurses working 12-hour shifts. Workplace Health & Safety. 2014;62(10):409–14. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20140826-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niu SF, Chu H, Chen CH, Chung MH, Chang YS, Liao YM, et al. A comparison of the effects of fixed- and rotating-shift schedules on nursing staff attention levels: a randomized trial. Biological Research in Nursing. 2013;15(4):443–50. doi: 10.1177/1099800412445907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trinkoff AM, Storr CL. Work schedule characteristics and substance use in nurses. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1998;34(3):266–71. Available online: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths P, Dall’Ora C, Simon M, Ball J, Lindqvist R, Rafferty AM, et al. Nurses’ shift length and overtime working in 12 European countries: the association with perceived quality of care and patient safety. Medical Care. 2014;52(11):975–81. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ball J, Day T, Murrells T, Dall’Ora C, Rafferty AM, Griffiths P, et al. Cross-sectional examination of the association between shift length and hospital nurses job satisfaction and nurse reported quality measures. BMC Nursing. 2017;16(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s12912-017-0221-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths P, Dall’Ora C, Sinden N, Jones J. Association between 12-hr shifts and nursing resource use in an acute hospital: Longitudinal study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2019;27(3):502–8. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dall’Ora C, Griffiths P, Ball J, Simon M, Aiken LH. Association of 12 h shifts and nurses’ job satisfaction, burnout and intention to leave: findings from a cross-sectional study of 12 European countries. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008331. Available online: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stimpfel AW, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Affairs. 2012;31(11):2501–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dall’Ora C, Griffiths P, Emmanuel T, Rafferty AM, Ewings S, Consortium RC. 12-hr shifts in nursing: Do they remove unproductive time and information loss or do they reduce education and discussion opportunities for nurses? A cross-sectional study in 12 European countries. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(1–2):53–9. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dall’Ora C, Griffiths P, Redfern O, Recio-Saucedo A, Meredith P, Ball J, et al. Nurses’ 12-hour shifts and missed or delayed vital signs observations on hospital wards: retrospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e024778. Available online: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trinkoff AM, Johantgen M, Storr CL, Gurses AP, Liang Y, Han K. Nurses’ work schedule characteristics, nurse staffing, and patient mortality. Nursing Research. 2011;60(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181fff15d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone PW, Du Y, Cowell R, Amsterdam N, Helfrich TA, Linn RW, et al. Comparison of nurse, system and quality patient care outcomes in 8-hour and 12-hour shifts. Medical Care. 2006;44(12):1099–106. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000237180.72275.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day G. Is there a relationship between 12-hour shifts and job satisfaction in nurses. Alabama State Nurses’ Association. 2004;31(2):11–2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ball J, Dall’Ora C, Griffiths P. The 12-hour shift: Friend or foe? Nursing Times. 2015;111(6):12–4. Available online at: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/patient-safety/the-12-hour-shift-friend-or-foe-30-01-2015/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferguson SA, Dawson D. 12-h or 8-h shifts? It depends. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2012;16(6):519–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. Available online: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis. 2020;18(10). doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matheson A, O’Brien L, Reid JA. Women’s experience of shiftwork in nursing whilst caring for children: A juggling act. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019;28(21–22):3817–26. Available online: 10.1111/jocn.15017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West S, Rudge T, Mapedzahama V. Conceptualizing nurses’ night work: an inductive content analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2016;72(8):1899–914. Available online: 10.1111/jan.12966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koy V, Yunibhand J, Turale S. "It is really so exhausting": Exploring intensive care nurses’ perceptions of 24‐hour long shifts. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(17/18):3506–15. Available online: 10.1111/jocn.15389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein M, Söderström M, Jirwe M, Tucker P, Dahlgren A. Sleep and fatigue in newly graduated nurses—Experiences and strategies for handling shiftwork. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(1–2):184–94. Available online: 10.1111/jocn.15076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gifkins J, Loudoun R, Johnston A. Coping strategies and social support needs of experienced and inexperienced nurses performing shiftwork. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2017;73(12):3079–89. Available online: 10.1111/jan.13374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Cordova PB, Phibbs CS, Stone PW. Perceptions and observations of off-shift nursing. Journal of Nursing Management. 2013;21(2):283–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01417.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bauer I. Nurses’ perception of the first hour of the morning shift (6.00–7.00 a.m.) in a German hospital. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1993;18(6):932–7. Available online: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18060932.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Books C, Coody LC, Kauffman R, Abraham S. Night shift work and its health effects on nurses. Health Care Manager. 2017;36(4):347–53. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nasrabadi AN, Seif H, Latifi M, Rasoolzadeh N, Emami A. Night shift work experiences among Iranian nurses: a qualitative study. International Nursing Review. 2009;56(4):498–503. 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horton Dias C, Dawson RM. Hospital and shift work influences on nurses’ dietary behaviors: A qualitative study. Workplace Health & Safety. 2020;68(8):374–83. doi: 10.1177/2165079919890351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centofanti S, Banks S, Colella A, Dingle C, Devine L, Galindo H, et al. Coping with shift work-related circadian disruption: A mixed-methods case study on napping and caffeine use in Australian nurses and midwives. Chronobiology International. 2018;35(6):853–64. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2018.1466798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao X, Jiang L, Hu Y, Li L, Hou L. Nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns in isolation wards during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020;29(21–22):4270–80. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baillie L, Thomas N. Changing from 12-hr to 8-hr day shifts: A qualitative exploration of effects on organising nursing care and staffing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019;28(1–2):148–58. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson L, Schneider J, Hare Duke L. Unregistered health care staff’s perceptions of 12 hour shifts: an interview study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2017;25(7):531–8. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGettrick KS, O’Neill MA. Critical care nurses: Perceptions of 12-h shifts. Nursing in Critical Care. 2006;11(4):188–97. 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2006.00171.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fallis WM, McMillan DE, Edwards MP. Napping during night shift: Practices, preferences, and perceptions of critical care and emergency department nurses. Critical Care Nurse. 2011;31(2):e1–e11. doi: 10.4037/ccn2011710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baillie L, Thomas N. How does the length of day shift affect patient care on older people’s wards? A mixed method study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2017;75:154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ose SO, Tjønnås MS, Kaspersen SL, Færevik H. One-year trial of 12-hour shifts in a non-intensive care unit and an intensive care unit in a public hospital: A qualitative study of 24 nurses’ experiences. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haller TM, Quatrara B, Letzkus LC, Keim-Malpass J. Nurses’ perceptions of shift length: What are the benefits? Nursing Management. 2018;49(10):38–43. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000546202.40080.c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rathore H, Shukla K, Singh S, Tiwari G. Shift work—problems and its impact on female nurses in Udaipur, Rajasthan India. Work. 2012;41:4302–14. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0725-4302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suter J, Kowalski T. The impact of extended shifts on strain-based work–life conflict: A qualitative analysis of the role of context on temporal processes of retroactive and anticipatory spillover. Human Resource Management Journal. 2020. 10.1111/1748-8583.12321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webster J, McLeod K, O’Sullivan J, Bird L. Eight-hour versus 12-h shifts in an ICU: Comparison of nursing responses and patient outcomes. Australian Critical Care. 2019;32(5):391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suter J, Kowalski T, Anaya-Montes M, Chalkley M, Jacobs R, Rodriguez-Santana I. The impact of moving to a 12 hour shift pattern on employee wellbeing: a qualitative study in an acute mental health setting. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020:103699. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reid N, Robinson G, Todd C. The 12-hour shift: the views of nurse educators and students. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;19(5):938–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01172.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parkinson J, Arcamone A, Mariani B. A pilot study exploring rehabilitation nurses’ perceptions of 12-hour shifts. Nursing. 2018;48(2):60–5. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000529817.74772.9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haller T, Quatrara B, Miller-Davis C, Noguera A, Pannone A, Keim-Malpass J, et al. Exploring perceptions of shift length: A state-based survey of RNs. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2020;50(9):449–55. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Landis TT, Wilson M, Bigand T, Cason M. Registered nurses’ experiences taking breaks on night shift: A qualitative analysis. Workplace Health & Safety. 2021:2165079920983018. doi: 10.1177/2165079920983018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Powell I. Can you see me? Experiences of nurses working night shift in Australian regional hospitals: a qualitative case study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013;69(10):2172–84. doi: 10.1111/jan.12079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faseleh Jahromi M, Moattari M, Sharif F. Novice nurses’ perception of working night shifts: a qualitative study. Journal of Caring Sciences. 2013;2(3):169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith A, McDonald AD, Sasangohar F. Night-shift nurses and drowsy driving: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moreno CRC, Marqueze EC, Sargent C, Wright KP Jr, Ferguson SA Jr., Tucker P. Working time society consensus statements: Evidence-based effects of shift work on physical and mental health. Industrial Health. 2019;57(2):139–57. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.SW-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akerstedt T, Wright KP Jr. Sleep loss and fatigue in shift work and shift work disorder. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2009;4(2):257–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sagherian K, Clinton ME, Abu-Saad Huijer H, Geiger-Brown J. Fatigue, work schedules, and perceived performance in bedside care nurses. Workplace Health & Safety. 2016;65(7):304–12. 10.1177/2165079916665398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barker LM, Nussbaum MA. Fatigue, performance and the work environment: a survey of registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011;67(6):1370–82. Available online: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodriguez Santana I, Anaya Montes M, Chalkley M, Jacobs R, Kowalski T, Suter J. The impact of extending nurse working hours on staff sickness absence: Evidence from a large mental health hospital in England. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;112:103611. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merrifield N. Essex trust switches to 12-hour nursing shifts to alleviate staffing and cost concerns. Nursing Times. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Todd C, Robinson G, Reid N. 12-hour shifts: job satisfaction of nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 1993;1(5):215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.1993.tb00216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stimpfel AW, Lake ET, Barton S, Gorman KC, Aiken LH. How differing shift lengths relate to quality outcomes in pediatrics. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2013;43(2):95–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Estryn-Behar M, Van der Heijden BI, Group NS. Effects of extended work shifts on employee fatigue, health, satisfaction, work/family balance, and patient safety. Work. 2012;41Suppl 1:4283–90. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0724-4283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Redfern O, Recio-Saucedo A, Maruotti A, Meredith P, et al. Are long nursing shifts on hospital wards associated with sickness absence? A longitudinal retrospective observational study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2019;27(1):19–26. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dall’Ora C, Dahlgren A. Shift work in nursing: closing the knowledge gaps and advancing innovation in practice. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020:103743. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Turunen J, Karhula K, Ropponen A, Koskinen A, Hakola T, Puttonen S, et al. The effects of using participatory working time scheduling software on sickness absence: A difference-in-differences study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;112:103716. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scott LD, Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Zhang Y. Effects of critical care nurses’ work hours on vigilance and patients’ safety. American Journal of Critical Care. 2006;15(1):30–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rogers AE, Hwang WT, Scott LD, Aiken LH, Dinges DF. The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. Health Affairs. 2004;23(4):202–12. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stimpfel AW, Aiken LH. Hospital staff nurses’ shift length associated with safety and quality of care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2013;28(2):122. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182725f09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ropponen A, Koskinen A, Puttonen S, Härmä M. Exposure to working-hour characteristics and short sickness absence in hospital workers: A case-crossover study using objective data. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2019;91:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burch JB, Tom J, Zhai Y, Criswell L, Leo E, Ogoussan K. Shiftwork impacts and adaptation among health care workers. Occupational Medicine. 2009;59(3):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hansen AB, Stayner L, Hansen J, Andersen ZJ. Night shift work and incidence of diabetes in the Danish nurse cohort. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2016;73(4):262–8. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2015-103342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ulaş T, Büyükhatipoğlu H, Kırhan İ, Dal MS, Eren MA, Hazar A, et al. The effect of day and night shifts on oxidative stress and anxiety symptoms of the nurses. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2012;16:594–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson AL, Jung L, Song Y, Brown KC, Weaver MT, Richards KC. Sleep deprivation and error in nurses who work the night shift. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2014;44(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Cordova PB, Bradford MA, Stone PW. Increased errors and decreased performance at night: A systematic review of the evidence concerning shift work and quality. Work. 2016;53:825–34. doi: 10.3233/WOR-162250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Flagg RL, Sparks A. Peer-to-peer education: Nighttime is the right time. Nursing Management. 2003;34(5):42–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilson M, Riedy SM, Himmel M, English A, Burton J, Albritton S, et al. Sleep quality, sleepiness and the influence of workplace breaks: A cross-sectional survey of health-care workers in two US hospitals. Chronobiology International. 2018;35(6):849–52. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2018.1466791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens SR, Harris M. Nurse staffing and inpatient hospital mortality. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364(11):1037–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1001025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rainbow JG. Presenteeism: Nurse perceptions and consequences. Journal of Nursing Management. 2019;27(7):1530–7. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steege LM, Rainbow JG. Fatigue in hospital nurses—’Supernurse’ culture is a barrier to addressing problems: A qualitative interview study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2017;67:20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lowson E, Arber S. Preparing, working, recovering: gendered experiences of night work among women and their families. Gender Work and Organization. 2014;21(3):231–43. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nijp HH, Beckers DG, Geurts SA, Tucker P, Kompier MA. Systematic review on the association between employee worktime control and work-non-work balance, health and well-being, and job-related outcomes. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2012;38(4):299–313. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, Aronsson G, Akerstedt T. The impact of work time control on physicians’ sleep and well-being. Applied Ergonomics. 2015;47:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stimpfel AW, Fletcher J, Kovner CT. A comparison of scheduling, work hours, overtime, and work preferences across four cohorts of newly licensed Registered Nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2019;75(9):1902–10. doi: 10.1111/jan.13972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data (i.e. references used for the scoping review) are within the manuscript with the corresponding URL or DOI.