Abstract

Purpose

Operating or riding on farm equipment is one of the leading causes of farm-related injuries and fatalities among children and adolescents. The aim of this study is to examine environment, crash, vehicle, and occupant characteristics and the probability of injury, given a crash, in youth under age 18 on farm equipment.

Method

Data from the Departments of Transportation on farm equipment related crashes across 9 Midwestern states from 2005–2010 were used. Odds ratios were calculated using logistic regression to assess the relationship between environment, crash, vehicle, and occupant characteristics and the probability of injury, given a crash.

Findings

A total of 434 farm equipment-related crashes involved 505 child or adolescent occupants on farm equipment: 198 passengers and 307 operators. Passengers of farm equipment had 4.1 higher odds of injury than operators. Occupants who used restraints had significantly lower odds of injury than those who did not. Furthermore, occupants on farm equipment that was rear-ended or sideswiped had significantly lower odds of injury compared to occupants on farm equipment involved in noncollision crashes. Likewise, occupants on farm equipment that was impacted while turning had significantly lower odds of injury compared to those on equipment that was impacted while moving straight.

Conclusion

Precautions should be taken to limit or restrict youth from riding on or operating farm equipment. These findings reiterate the need to enforce policies that improve safety measures for youth involved in or exposed to agricultural tasks.

Children play an integral role on the family farm by assisting with numerous tasks that include transporting goods to, from, and around the farm. The agriculture industry is known as one of the most dangerous occupational sectors worldwide with 2 times the rate of occupational deaths compared to any other industry.[1] As a result, in the United States, approximately 14,000 youth were injured in the agricultural setting in 2012. Although the annual number of farm-related injuries in youth has declined substantially since 2001, the Midwestern region still accounts for over 50% of farm-related injuries in youth under age 20.[2] Furthermore, with the use of death certificates from 1995 to 2000, an annual death rate of 9.[3] per 100,0003 was estimated among the approximately 1.5 million children living and working on farms.[4] Operating or riding on farm equipment is one of the leading causes of farm-related injuries and fatalities among children and adolescents.[5–7] Twenty percent to 34% of farm injuries and fatalities among youth were due to rollovers or run overs resulting in falls, crush injuries, or amputations.[7–9] Youth ages 5–9 accounted for the highest proportion of farm-related injuries due to farm equipment. Furthermore, children under 5 years of age were more likely to be injured while riding on a tractor than any other mechanism.[7] Boys were more likely to be operators of these vehicles[10] and consequently more likely to be injured compared to girls.[3,11,12]

Childhood risk of farm-related injuries is often attributed to a mismatch of developmental abilities with the hazardous jobs on the farm. Although childhood involvement in farm operations can be helpful for the farm and provide learning opportunities for children, it is essential that these tasks be developmentally appropriate.[13] For example, young children lack the size, reach, vision and strength to adequately maneuver large farm equipment on the roadways.[7,14,15] Youth have immature decision making and reasoning skills which are vital to operate farm equipment on the roads safely and in a strategic manner.[5–8] These disadvantages have led to the development of the North American Guidelines for Children’s Agricultural Tasks (NAGCAT),[13] which suggests agricultural tasks be based on the youth’s age and developmental stage. According to these guidelines, youth who are under age 14 should be restricted from operating farm equipment such as tractors. Despite these guidelines, operating farm equipment continues to be one of the most common agricultural tasks conducted by youth as young as 9 years.[16]

The aftermath of nonfatal farm-related injuries in youth places a tremendous burden on society. The economic cost of US farm-related injuries in 1 year is estimated at $1 billion in health care expenses, decreased productivity of the farming operation, and diminished quality of life for the victims.[17] Fifty-four percent of the projected cost was attributed to the physical and psychological burden placed on the family and youth after sustaining and surviving a traumatic incident. Furthermore, up to 41% of nonfatal farm injury cases resulted in long-term disabilities[18,19] that may later foster mental health disorders.6

Little is known about the mechanisms and contributing factors of youth-involved farm equipment-related crashes, especially for crashes that cause nonfatal injuries. The few previous studies that aimed to identify risk factors of injuries resulting from farm equipment-related crashes focused on the adult population or compared the occurrence of injury between occupants of farm and nonfarm vehicles.[10,20–22] Using data on farm equipment-related crashes that occurred on public roads across multiple states, the aim of this study was to examine crash, environment, vehicle, and occupant characteristics and the probability of injury, given a crash, for youth occupants under age 18 on farm equipment.

Methods

Data Source

Data used for this study were collected by law enforcement traffic officers and maintained by the Departments of Transportation in 9 Midwestern states: Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, Illinois, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Missouri. These data were restricted to crashes occurring on public roads that involved farm equipment and incurred more than $1,000 in damage. State data sets were compiled, collapsed, and recoded into 1 hierarchical data set that described the crash, environment, vehicle, and occupants. Farm equipment was defined as a vehicle designed or constructed for agricultural purposes and used exclusively in an agricultural operation; examples include combines, tractors, sprayers, and wagons or grain carts and exclude all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), utility task vehicles (UTVs), and recreational off-highway vehicles (ROVs). All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa Internal Review Board (IRB).

Study Population

We analyzed data collected from 2005 through 2010. The study population included occupants on farm equipment who were under age 18 at the time of the crash that occurred on public roads within the 9 states. Vehicle type categorized as farm equipment and ages less than 18 identified crash reports involving farm equipment with child or adolescent occupants. Youth with missing information on vehicle (n = 2), injury status (n = 10), and position (n = 14) were excluded from the study sample.

Study Variables

The outcome of interest was injury at the person level reported by the law enforcement traffic officer on the crash report form as fatal, incapacitating injury, nonincapacitating injury, possible injury, and no injury. As done in prior literature, no injury and possible injury were combined into 1 category to create a dichotomous variable of injury and no injury.[10] Exposures of interest included crash-, environment-, vehicle-, and person-level characteristics. Crash-level characteristics included state and year. Environment-level characteristics included season, lighting, and weather. Season was categorized based on agricultural practices using the date of the crash: harvest (September-December), planting (April-May), growing (June-August), and winter (January-March). Lighting was collapsed into dark, light, and other (ie, dusk, dawn, and other), and weather was collapsed into clear, cloudy, and other (ie, rain, snow, fog/smog/smoke, and other). Vehicle-level characteristics included impact type and vehicle action. Impact was recoded from multiple categories into noncollision, rear-ended, sideswiped/hit at an angle, and other collisions (ie, head-on and other). The noncollision category included overturns/rollovers (n = 17), collisions with fixed objects (n = 26) or parked vehicles (n = 4), and other noncollisions (n = 17). Vehicle action was collapsed into turning left or right, straight, and other (ie, overtaking/passing, changing lanes, entering/leaving traffic lane, backing, slowing/stopping, and parked). Person-level characteristics included position (driver/passenger), gender (male/female), and configuration of the occupants on the farm equipment (ie, child driver only; child driver and child passenger; adult driver and child passenger). The restraints used variable (yes/no) consisted of seat belts, child safety restraints, and helmets. Age was recoded into a categorical variable to align with the developmental stages set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention[23]: 0–5, 6–11, 12–14, and 15–17.

Analysis

Univariate analysis was conducted to report the distribution of all variables using percent and frequencies. Age, restraints used, injury, and sex were stratified by position to identify descriptive patterns. Chi-square or fisher exact bivariate analysis was used to identify associations between exposures of interest and the outcome, injury. Covariates with a P < .25 were included in the logistic model. Collinearity between covariates was evaluated using the Pearson correlation test and defined by a coefficient greater than 0.5. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to calculate the odds of experiencing an injury, given a crash, for crash-, environment-, vehicle-, and person-level variables. Youth with information missing on vehicle action (n = 10), manner (n = 6), light conditions (n = 15), sex (n = 1), and weather (n = 3) were excluded from the logistic regression analyses. Twenty-three percent of the study sample had missing data for the restraints used variable. Therefore, 2 separate analyses—with and without the restraints used variable—were conducted. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were reported. All analyses were done using SAS, version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

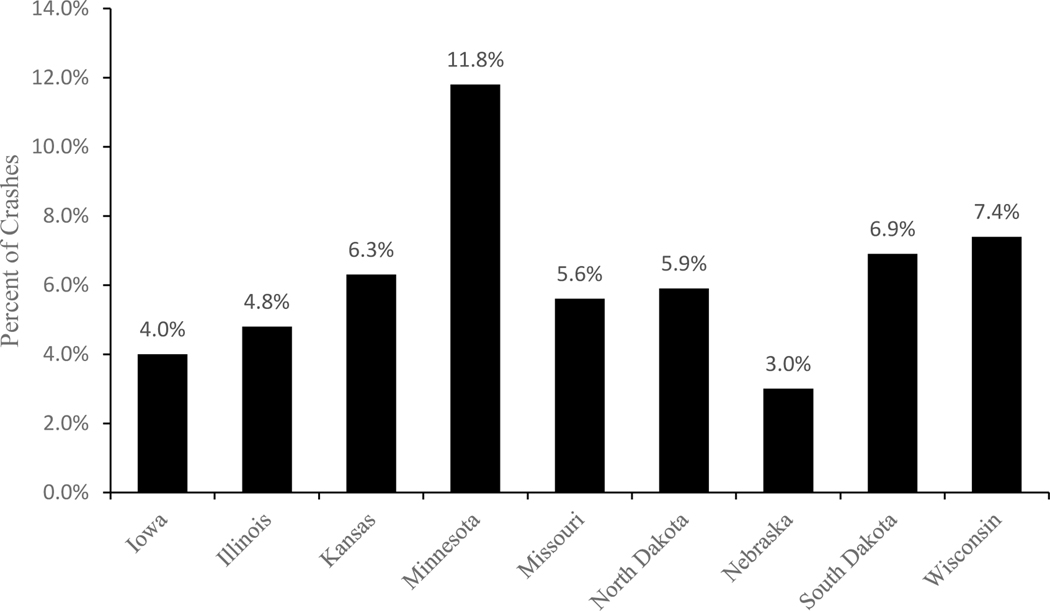

Of the 7,085 farm equipment-related crashes identified across the 9 Midwestern states from 2005 to 2010, 434 (6.1%) involved 505 child or adolescent occupants on farm equipment (Table 1). The number of crashes was consistent across the 5-year period. The most frequent youth occupant configuration was child driver only (66%) followed by adult driver and child passenger (30%). The least frequent configuration was child driver and child passenger at 4%. A substantial proportion of farm equipment-related crashes occurred during clear weather (79%), during the growing season (42%), at daylight (78%), or while the farm equipment was traveling straight (51%). Almost half of all impacts occurred at an angle or sideswiped (49%) followed by rear-ended (21%) and noncollisions (15%). The proportion of crashes occurring in each state that involved youth occupants on farm equipment ranged from 3% to 12% (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Crash Characteristics of Farm Equipment-Related Crashes Involving Children and Adolescents on Farm Equipment From 2005 to 2010 (N = 434)a

| Crash Characteristics | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Year | |

| 2005 | 78 (18.0) |

| 2006 | 67 (15.4) |

| 2007 | 75 (17.3) |

| 2008 | 66 (15.2) |

| 2009 | 77 (17.7) |

| 2010 | 71 (16.4) |

| Occupant Configuration | |

| Child driver | 289 (66.6) |

| Child driver & Child passenger | 17 (3.9) |

| Adult driver & Child passenger | 128 (29.5) |

| Season | |

| Winter | 40 (9.2) |

| Planting | 54 (12.4) |

| Growing | 180 (41.5) |

| Harvest | 160 (36.9) |

| Light Conditions | |

| Daylight | 338 (78.1) |

| Dark | 82 (18.9) |

| Otherb | 13 (3.0) |

| Farm vehicle action | |

| Straight | 218 (51.3) |

| Turning | 173 (40.7) |

| Otherc | 34 (8.0) |

| Impact | |

| Noncollision | 64 (14.9) |

| Rear-ended | 89 (20.8) |

| Angle/Sideswiped | 208 (48.5) |

| Other collisionsd | 68 (15.9) |

| Weather | |

| Clear | 343 (79.4) |

| Cloudy | 68 (15.7) |

| Othere | 21 (4.9) |

Sample size includes crashes with missing data.

Dusk, dawn, & other.

Overtaking/passing, changing lanes, entering/leaving traffic lane, backing, slowing/stopping & parked.

Head-on & other.

Rain, snow, fog/smog/smoke, & other

Figure 1.

The Proportion of Farm Equipment-Related Crashes in Each State That Involved Youth on Farm Equipment.

More youth occupants in crashes were drivers (n = 307, 61%) than passengers (n = 198, 39%) (Table 2). The proportion of youth involved in farm equipment-related crashes as drivers increased with age, from 11% in the 6–11 age group to 81% of those aged 15–17, while involvement as a passenger decreased with age. Boys were more often the driver (71%) than girls (19%). Passengers accounted for 61% of those who used restraints, yet they comprised 57% of those who were injured. Passengers (n = 59) and operators (n = 49) were reported wearing seat belts while child safety restraints (n = 21) or helmets (n = 1) were only used by passengers (not tabled).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Youth Occupants on Farm Equipment Involved in Collisions From 2005 to 2010, by Position (N = 505)a N(%)

| Driver 307 (61.8) | Passenger 198 (39.2) | Total (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occupant Characteristics | |||

| Age | |||

| 0–5 | 0 | 41 (100.0) | 41 |

| 6–11 | 11 (13.3) | 72 (86.8) | 83 |

| 12–14 | 70 (68.6) | 32 (31.4) | 102 |

| 15–17 | 226 (81.0) | 53 (19.0) | 279 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 18 (18.6) | 79 (81.4) | 97 |

| Male | 288 (70.8) | 119 (29.2) | 407 |

| Restraints usedb | |||

| Yes | 52 (38.8) | 82 (61.2) | 134 |

| No | 165 (65.0) | 89 (35.0) | 254 |

| Injuryc | |||

| Injured | 30 (43.5) | 39 (56.5) | 69 |

| Not injured | 277 (63.5) | 159 (36.5) | 436 |

Sample size includes youth with missing data.

Seat belts, child safety restraints, or helmets.

Not injured category includes no injury & possible injury.

Passengers of farm equipment had a 4.10 (95% CI: 1.88–8.94) higher odds of experiencing an injury compared to drivers of farm equipment (Table 3). We also observed 1.30 (95% CI: 0.60–2.81) higher odds of injury in youth occupants 12–14 years compared to those 15–17 years but this estimate was also not statistically significant. If restraints were used, adjusted odds ratios demonstrated significantly lower odds of injury compared to those who did not use restraints (OR = 0.12, 95% CI: 0.03–0.40) (not tabled).

Table 3.

Odds of Injury for Youth Occupants on Farm Equipment Involved in Collisions From 2005 to 2010 (N = 474)

| Injurya | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Not Injured N (%) | Injured N (%) | cOR (95% CI)b | aOR (95% CI)c | |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Occupant | ||||

| Driver | 277 (90.2) | 30 (9.8) | Ref | Ref |

| Passenger | 159 (80.3) | 39 (19.7) | 2.27 (1.35–3.79) | 4.10 (1.88–8.94) |

| Age | ||||

| 0–5 | 38 (92.7) | 3 (7.3) | 0.61 (0.18–2.09) | 0.22 (0.05–0.92) |

| 6–11 | 66 (79.5) | 17 (20.5) | 1.99 (1.04–3.80) | 0.70 (0.28–1.73) |

| 12–14 | 85 (83.3) | 17 (16.7) | 1.54 (0.82–2.92) | 1.30 (0.60–2.81) |

| 15–17 | 247 (88.5) | 32 (11.5) | Ref | Ref |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 81 (83.5) | 16 (16.5) | 1.32 (0.72–2.43) | 0.79 (0.36–1.73) |

| Male | 354 (87.0) | 53 (13.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Crash Characteristics | ||||

| Light Conditions | ||||

| Daylight | 345 (87.8) | 48 (12.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Dark | 77 (79.4) | 20 (20.6) | 1.87 (1.05–3.33) | 1.55 (0.73–3.27) |

| Farm vehicle action | ||||

| Straight | 202 (79.8) | 51 (20.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Turning | 184 (94.9) | 10 (5.2) | 0.22 (0.11–0.44) | 0.42 (0.18–0.95) |

| Other | 38 (86.4) | 6 (13.6) | 0.63 (0.25–1.56) | 0.67 (0.24–1.90) |

| Impact | ||||

| Noncollision | 48 (60.0) | 32 (40.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Rear-ended | 86 (83.5) | 17 (16.5) | 0.30 (0.15–0.59) | 0.26 (0.11–0.59) |

| Angle/Sideswiped | 224 (96.1) | 9 (3.7) | 0.06 (0.03–0.13) | 0.07 (0.03–0.18) |

| Other collisions | 75 (90.4) | 8 (9.6) | 0.16 (0.07–0.38) | 0.19 (0.07–0.52) |

| Weather | ||||

| Clear | 346 (87.8) | 48 (12.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Cloudy | 65 (84.4) | 12 (15.6) | 1.33 (0.67–2.64) | 0.92 (0.40–2.12) |

| Other | 22 (71.0) | 9 (29.0) | 2.95 (1.28–6.78) | 0.73 (0.25–2.13) |

Crude odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals, and model controls for covariates.

Other category was excluded due to an insufficient number of injured youth.

Youth occupants of crashes that occurred during the dark had 1.55 (95% CI: 0.73–3.27) higher odds of injury compared to those involved in crashes that occurred during daylight, but this estimate was not statistically significant. Occupants of farm equipment that were rear-ended (OR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.11–0.59) or impacted by sideswipe or at an angle (OR = 0.07, 95% CI: 0.03–0.18) had significantly lower odds of experiencing an injury compared to youth occupants involved in noncollision crashes. Occupants on farm equipment turning left or right had significantly lower odds of injury compared to occupants on farm equipment moving straight (OR = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.18–0.95).

Discussion

Youth passengers had more than 4 times the odds of being injured compared to youth drivers, given a crash— a finding that aligns with the common knowledge that most farm equipment, specifically tractors, are not equipped for passengers or the safety of passengers.[24,25] Of the 198 passengers identified, 90% were driven by adults—even with an adult driver, child passengers were still at risk for sustaining an injury. These data add to increasing evidence that agricultural activities need to be carefully assigned and supervised when being performed by youth.[5,12,26] Although there is a common cultural practice among farm families to have their small children take rides on tractors, injuries to child passengers could be prevented if parents refrain from allowing children to ride on tractors on and off the farm.

Youth occupants who wore restraints had half the odds of injury compared to those who did not. Child safety restraints for young children were of particular interest since farm equipment is generally unable to accommodate a passenger, let alone a child safety seat. Adults who restrained their children were likely aware that riding on farm equipment may be potentially dangerous for a child, and attempted to take steps to protect their child against potential injury. It is encouraging that restraints were used but we are uncertain if the use of child safety seats effectively prevents injuries given a farm equipment-related crash. Continued efforts to reduce children from riding on farm equipment and increase the use of seat belts when a passenger seat is present should be undertaken to prevent injuries and fatalities.

Sixty-nine percent of youth between 12 and 14 years of age were operators of farm equipment and had 1.3 higher odds of injury compared to youth between ages 15 and 17 years. Although this estimate was not statistically significant, it may still support restricting youth younger than 15 from operating farm equipment on the roadways. Most youth get their driver’s permit and begin driving between the ages of 14 and 15, and experience driving a vehicle may contribute to safe farm equipment operation on the roadway. The NAGCAT recommends that youth should not operate farm equipment on roadways until age 16,[13] and potentially not until they are licensed drivers. Despite the growing acceptance of NAGCAT among researchers and health professionals, many parents are either unaware of or disregard these guidelines. For instance, youth who work on farming operations owned by their parents were more likely to be assigned agricultural tasks at a younger age than what is recommended by the NAGCAT[16,27] and were more likely to be injured[12] compared to youth working on nonfamily farms, in spite of parents being cognizant of the NAGCAT recommendations.28 As researchers, we should continue to encourage the use of these guidelines by both parents and youth and place our efforts on disseminating this information to farm families across the country in order to reduce preventable injuries.

Occupants on farm equipment that was rear-ended, sideswiped, or hit at an angle had significantly lower odds of injury compared to occupants on farm equipment involved in a noncollision. Noncollisions consist of rollovers or overturns, both of which may result in more severe injuries and are more often fatal. In contrast, a study consisting primarily of adult drivers found that the odds of an injury occurring was higher if the farm equipment was rear-ended or sideswiped.10 Seat belt use and the presence of rollover protective structures (ROPS) are effective in reducing severe or fatal injuries during an overturn or rollover.[29,30] Despite this, a survey conducted among high school students enrolled in agricultural courses in 3 states found that youth frequently reported engaging in high-risk behaviors including operating farm equipment that lacked the necessary safety features.[31] Approximately 45% disclosed that their most frequently used tractor was not equipped with a ROPS and seat belt. Federal law requires that tractors manufactured after October 25, 1976, and operated by an employee be equipped with both devices.[32] However, 71% of these students were household youth and therefore are not protected by regulatory policies.[31] This policy should be revised to prohibit all youth from operating tractors that lack the necessary safety features of ROPS and seat belts.

Environmental factors such as weather and lighting did not contribute significantly to the risk of an injury due to a crash. Although statistically nonsignificant, the increased odds of injury in crashes that occurred in the dark are consistent with studies conducted by Gkritza et al[22] and Peek-Asa et al.[10] Studies have attributed crash injuries to low/limited visibility.[10,22,33] Generally, higher rates of crashes occur during the harvest season when crops are being transported from the farm.[10,22] We found crash occurrence to be equally high in the harvest and growing season. For youth, the growing season coincides with the summer vacation when kids are out of school and are more available to assist on or around the farm.[12] The proportion of farm equipment-related crashes that involved youth differed across the 9 participating states, although we cannot assess if this is due to an increase in youth exposure to farm equipment on roadways or an increased risk while driving on them. An evaluation comparing the effectiveness of state policies on age restrictions for employment in the agricultural industry and operating farm equipment on public roadways could provide reasoning for the differences observed between states. This may provide additional information on the policies that are implemented and are effective at reducing farm equipment crashes involving youth.

Limitations

Lack of exposure data precludes calculation of incidence rates. Higher proportions of some variables may indicate more exposure rather than greater risk. We defined the driver position as the front left seat of the farm equipment, which may not be the case for a small percentage of farm equipment where the driver may be located in the front middle or right seat. Since this configuration is rare, it is not likely to affect results reported here. Although a definition of farm equipment was provided by the Departments of Transportation, what is categorized as farm equipment at the scene of the crash was left to the discretion of the traffic officer and may not be consistent between reports. Injury status was dichotomized into yes/no categories; the no category included no injury and possible injury. In both instances, misclassification may have occurred, causing bias and inaccurate estimate of the measure of associations. The use of an alternate data set such as hospital data will eliminate the possible injury category along with any potential biases. Finally, the relatively small sample of injured youth (n = 69) may have led to reduced power, resulting in nonsignificant findings in our multivariable regression models.

Conclusion

No matter who is driving, passengers of farm equipment are at risk for sustaining an injury in a crash. Despite the substantial evidence that disputes the practice of allowing young children and adolescents to operate or ride on tractors, to date, it is still frequently performed. Collaborations between researchers, pediatricians, or community-based organizations such as 4-H, Future Farmers of America, and agriculture extension offices are just a few ways to increase dissemination, awareness, and use of the NAGCAT. It is important that parents or caregivers continue to be educated on when and how to allow youth to contribute and assist with transporting goods to, from, and around the farm.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Iowa Great Plains Center for Agricultural Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health [U50 OH007548–11]. The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.International Labour Organization. Agriculture: a hazardous work. Occup Saf Health. 2015. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/safework/areasofwork/hazardouswork/WCMS_356550/lang–en/index.htm.Accessed April 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Division of Safety Research. Childhood Agricultural Injury Survey (CAIS) results: national estimates of injuries to all youth (<20 years) on U.S. farms by type of youth. Childhood Agricultural Injury Prevention Initiative. April7, 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/childag/cais/injtables.html.Accessed April 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldcamp M, Hendricks KJ, Myers JR. Farm fatalities to youth 1995–2000: a comparison by age groups. J Safety Res. 2004;35(2):151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injuries to youth on farms and safety recommendations, U.S. 2006. Washington, DC: NIOSH; 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2009-117/pdfs/2009-117.pdf.Accessed February 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwebel DC, Pickett W. The role of child and adolescent development in the occurrence of agricultural injuries: an illustration using tractor-related injuries. J Agromedicine. 2012;17(2):214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright S, Marlenga B, Lee BC. Childhood agricultural injuries: an update for clinicians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2013;43(2):20–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivara FP. Fatal and non-fatal farm injuries to children and adolescents in the United States, 1990–3. Inj Prev. 1997;3(3):190–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little DC, Vermillion JM, Dikis EJ, Little RJ, Custer MD, Cooney DR. Life on the farm—children at risk. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(5):804–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivara FP. Fatal and nonfatal farm injuries to children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1985;76(4):567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peek-Asa C, Sprince N, Whitten P, Falb S, Madsen M, Zwerling C. Characteristics of crashes with farm equipment that increase potential for injury. J Rural Health. 2007;23(4):339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hendricks K, Myers JR, Layne LA, Goldcamp EM. Injuries to youth living on U.S. farms in 2001 with comparison to 1998. J Agromedicine. 2005;10(4):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bancej C, Arbuckle T. Injuries in Ontario farm children: a population based study. Inj Prev. 2000;6(2):135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation. Tractor fundamentals: tractor operation chart. North American Guidelines for Children’s Agricultural Tasks. Available at: http://www.nagcat.org/proxy/MCRF-Centers-NFMCNAGCAT-Guidelines-PDF-T1.2.pdf.Accessed February 19, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fathallah FA, Chang JH, Pickett W, Marlenga B. Ability of youth operators to reach farm tractor controls. Ergonomics. 2009;52(6):685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang JH, Fathallah FA, Pickett W, Miller BJ, Marlenga B. Limitations in fields of vision for simulated young farm tractor operators. Ergonomics. 2010;53(6):758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marlenga B, Pickett W, Berg RL. Assignment of work involving farm tractors to children on North American farms. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Lee B. Incidence and cost of nonfatal farm youth injury, United States, 2001–2006. J Agromedicine. 2010;16(1):6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed DB, Claunch DT. Nonfatal farm injury incidence and disability to children. Am J Prev Med. 2000;14(4S):70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson J, Sachs M, Dahlgren K, Tinguely S. Accidental farm injuries in children. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141: 1276–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costello TM, Schulman MD, Mitchell RE. Risk factors for a farm vehicle public road crash. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41(1):42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson K, Gerberich SG, Church T, et al. Tractor-related injuries: a population-based study of a five-state region in the Midwest. Am J Ind Med. 2005;47(3):254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gkritza K, Kinzenbaw CR, Hallmark S, Hawkins N. An empirical analysis of farm vehicle crash injury severities on Iowa’s public road system. Accid Anal Prev. 2010;42(4):1392–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Division of Human Development and Disabilities, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child development. positive parenting tips. 2014. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/index.html.Accessed February 19, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwab C. Extra riders mean extra dangers—safe farm. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. Ames, Iowa; 2013. Available at: https://store.extension.iastate.edu/Product/Extra-riders-mean-extra-dangers-Safe-Farm.Accessed January 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farm Safety Association Inc. A guide to safe farm tractor operation. 2003. Available at: http://nasdonline.org/document/1659/d001534/a-guide-to-safe-farmtractor-operation.html.Accessed January 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrongiello B, Zdzieborski D, Stewart J. Supervision of children in agricultural settings: implications for injury risk and prevention. J Agromedicine. 2012;17(2):149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, Ogara E, Cheng G, et al. At what age should children engage in agricultural tasks? J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickett W, Marlenga B, Berg RL. Parental knowledge of child development and the assignment of tractor work to children. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1):E11–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelsey TW, May JJ, Jenkins PL. Farm tractors, and the use of seat belts and roll-over protective structures. Am J Ind Med. 1996;30(4):447–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers ML, Cole HP, Westneat SC. Seatbelt use during tractor overturns. J Agric Saf Health. 2006;12(1): 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed D, Browning S, Westneat S, Kidd P. Personal protective equipment use and safety behaviors among farm adolescents: gender differences and predictors of work practices. J Rural Health. 2006;22(4):314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Occupational Safety & Health Administration, United States Department of Labor. Roll-over protective structures (ROPS) for tractors used in agricultural operations. 1928.51. 2005. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=10957.Accessed January 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerberich SG, Robertson LS, Gibson RW, Renier C. An epidemiological study of roadway fatalities related to farm vehicles: United States, 1988 to 1993. J Occup Environ Med. 1996;38(11):1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]