Abstract

Aims.

Young adults with early psychosis want to pursue normal roles – education and employment. This paper summarises the empirical literature on the effectiveness of early intervention programmes for employment and education outcomes.

Methods.

We conducted a systematic review of employment/education outcomes for early intervention programmes, distinguishing three programme types: (1) those providing supported employment, (2) those providing unspecified vocational services and (3) those without vocational services. We summarised findings for 28 studies.

Results.

Eleven studies evaluated early intervention programmes providing supported employment. In eight studies that reported employment outcomes separately from education outcomes, the employment rate during follow-up for supported employment patients was 49%, compared with 29% for patients receiving usual services. The two groups did not differ on enrolment in education. In four controlled studies, meta-analysis showed that the employment rate for supported employment participants was significantly higher than for control participants, odds ratio = 3.66 [1.93–6.93], p < 0.0001. Five studies (four descriptive and one quasi-experimental) of early intervention programmes evaluating unspecified vocational services were inconclusive. Twelve studies of early intervention programmes without vocational services were methodologically heterogeneous, using diverse methods for evaluating vocational/educational outcomes and precluding a satisfactory meta-analytic synthesis. Among studies with comparison groups, 7 of 11 (64%) reported significant vocational/education outcomes favouring early intervention over usual services.

Conclusions.

In early intervention programmes, supported employment moderately increases employment rates but not rates of enrolment in education. These improvements are in addition to the modest effects early programmes alone have on vocational/educational outcomes compared with usual services.

Key words: Early intervention, early psychosis, employment, supported employment

Introduction

Young adults experiencing early psychosis want to work (Iyer et al. 2011; Ramsay et al. 2011). Many also want to pursue education, either in conjunction with employment or as preparation for employment (Nuechterlein et al. 2008). Vocational and educational issues are common reasons clinicians refer patients to early intervention programmes (Cotton et al. 2011).

Early intervention programmes were pioneered in Australia (McGorry et al. 1996, 2008) and subsequently spread across wealthy countries. These programmes have varied in their specific offerings, but most seek to identify people early in the course of psychotic illness and help them to achieve rapid remissions, prevent relapses and maintain functioning. No standard model of early intervention has yet emerged, although most experts endorse several core principles, such as early detection, family psychoeducation and assertive outreach (Addington et al. 2013; Hughes et al. 2014). Early formulations of the early intervention models recognised the importance of role functioning, but mainly restricted interventions in this area to social skills training. The short-term clinical effectiveness of the early intervention programmes is promising (Malla et al. 2005), but their long-term effectiveness remains uncertain (Yung, 2012). Although two narrative reviews have examined supported employment for patients with early psychosis (Killackey et al. 2006; Rinaldi et al. 2010a), no review has comprehensively examined employment and education outcomes in early intervention programmes.

Three recent developments suggest that employment services may play a crucial role in early intervention programmes. First, the early intervention has renewed hope for altering the course of psychotic illnesses, in part because these young people are highly motivated to pursue functional outcomes. People with early psychosis want help finding employment: thus employment services serve as an engagement strategy for enhancing participation in treatment. Second, following the success of supported employment in helping people with long-term serious mental illness to achieve competitive employment (Marshall et al. 2014), clinicians and researchers are adopting supported employment in early intervention programmes (Killackey et al. 2006). Young adults with mental illness appear to benefit as much, if not more, from supported employment than do their older counterparts (Browne & Waghorn, 2010; Burke-Miller et al. 2012; Ferguson et al. 2012; Bond et al. in press). Third, helping young adults experiencing early psychosis to gain employment may prevent disability. People develop schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses early in life, typically between the ages of 16 and 26. During this developmental period, most people are making important transitions to adulthood, including finishing their educations and establishing their identities as workers. The onset of psychosis often interrupts this life trajectory (Yung, 2012), in part due to professional advice to accept long periods of treatment and functional inactivity in order to achieve stability and prevent relapses (Bassett & Lloyd, 2001).

This paper provides a systematic review of the literature on the impact of early intervention services on employment and education outcomes for people experiencing early psychosis, defined as the first 6 months of experiencing psychotic symptoms (Caton et al. 2005). We hypothesised that the patients receiving supported employment based on evidence-based principles would achieve improved employment outcomes compared with baseline levels and to patients receiving services as usual. Secondarily, we hypothesised that participation in supported employment would increase enrolment rates in mainstream educational programmes.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a systematic review of employment and education outcomes for early intervention programmes, summarising outcomes for all studies reporting relevant longitudinal outcomes. As supported employment was the most frequently studied employment model, we examined it separately and in more detail.

Study inclusion criteria

We included longitudinal studies of early intervention programmes with at least ten participants reporting vocational/educational outcomes (defined broadly to include a range of indicators and scales). We included studies with uncontrolled, quasi-experimental and experimental designs.

Literature search procedures

Our literature search strategies included electronic searches of MEDLINE and of publications within the journal, Early Intervention in Psychiatry; a manual search of conference proceedings from three recent meetings of the International Early Psychosis Association; two published reviews (Rinaldi et al. 2010a; Skalli & Nicole, 2011); and manual screening of reference lists of all included studies.

We identified articles from the international literature on employment interventions among young adults with serious mental illness by searching PubMed/MEDLINE from inception to April, 2013, using key words to generate sets of records, combined by the Boolean term ‘OR,’ for the following themes: severe mental illness (‘psychosis,’ ‘schizophrenia,’ ‘bipolar disorder,’ and ‘disorders with psychotic features’), employment (‘job placement,’ ‘employment,’ ‘vocational rehabilitation,’ ‘supported employment,’ ‘individual placement and support’ and ‘occupation’) and young adulthood (‘young adult,’ ‘first episode,’ ‘first-episode’ and ‘early intervention’), restricted to English-language publications. We combined themes using the Boolean term ‘AND’ to find their intersections. Using similar search terms, we also performed an electronic search of Early Intervention in Psychiatry. Based on the abstracts from these two searches, the first author identified references for full-text review, which the first and third authors then independently assessed to determine appropriateness for inclusion. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Classification of treatments and studies

We distinguished three types of early intervention programmes: (1) those providing supported employment services, (2) those with an unspecified vocational component and (3) those without an identified vocational component.

The most widely accepted model of supported employment for adults with severe mental illness is Individual Placement and Support (IPS). It is an evidence-based model of supported employment (Marshall et al. 2014), guided by eight principles: eligibility based on consumer choice, focus on competitive employment, integration of mental health and employment services, attention to patient preferences, work incentives planning, rapid job search, systematic job development and individualised job supports (Drake et al. 2012). Programmes adhering to these principles, as measured by an IPS fidelity scale, generally have better competitive employment outcomes (Bond et al. 2011). For young adults with early psychosis, IPS has been expanded to include supported education as well as supported employment (Nuechterlein et al. 2008). In this report, we use the term ‘supported employment’ to include both programmes closely following the IPS model as well as those not explicitly adhering to IPS fidelity standards.

Outcome measures

Although our intent was to focus on studies reporting competitive employment at baseline and follow-up, we broadened the inclusion criteria to include studies reporting any vocational outcomes, including studies reporting findings for occupational functioning scales. In addition, some studies combined employment and education outcome into a single measure. When available, we also recorded rates of enrolment in education.

Review methods and data analysis

We summarised study characteristics and main findings for all studies meeting inclusion criteria. Heterogeneity of outcome measures precluded aggregating results for early intervention without an identified vocational component or an unspecified vocational component. As it was possible, we examined the supported employment studies in greater detail, using tabular reporting to facilitate study comparisons and aggregating follow-up employment and education rates. We tested the significance of differences in rates at follow-up using chi squares (χ2) and calculated the effect size (ES) for the rate differences between supported employment and controls using the arc sine approximation (Lipsey, 1990). Using RevMan (2012), a computer software program used in Cochrane meta-analytic reviews, we evaluated aggregate employment and education for supported employment studies with comparison groups. This computer software generates forest plots displaying effect sizes weighted by sample sizes.

Results

Search results

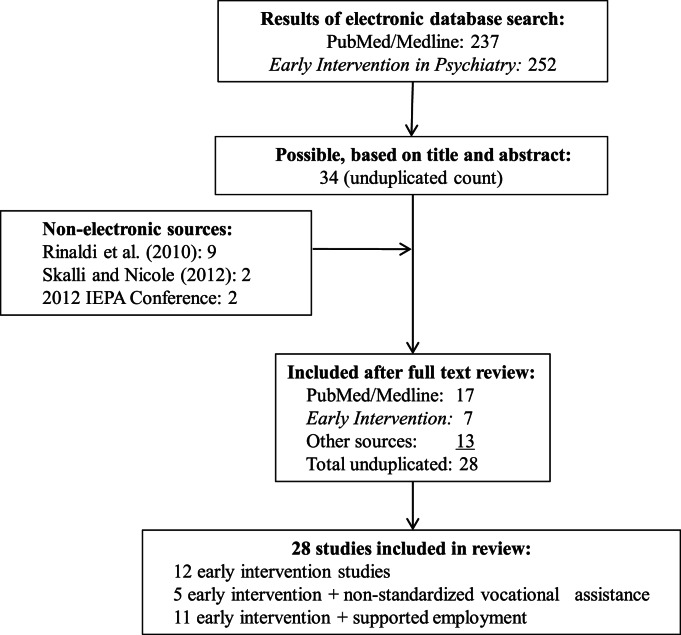

As outlined in Fig. 1, the electronic searches yielded 237 and 252 references, respectively, from PubMed/MEDLINE and Early Intervention in Psychiatry, resulting in 34 publications for full-text review (26 and 13, respectively, with five duplicates). We identified 13 additional studies from other sources and conducted full-text reviews on unduplicated studies. Finally, we identified 28 studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

Search results for systematic review of early psychosis and employment literature.

Early intervention programmes offering supported employment

We identified 11 studies of early intervention programmes offering supported employment, as shown in Table 1. These included four uncontrolled evaluations (Rinaldi et al. 2004, 2010b; Porteous & Waghorn, 2007, 2009), four controlled and quasi-controlled trials reporting employment and education rates at baseline and follow-up (Killackey et al. 2008, 2012; Major et al. 2010; Nuechterlein et al. submitted for publication), all of which reported separate statistics for employment and education, and three studies of early intervention programmes providing supported employment outcomes for a combined measure of employment and education, preventing their inclusion in our tabled results (Singh et al. 2007; Fowler et al. 2009a; Dudley et al. 2014).

Table 1.

Evaluation studies of early intervention programmes reporting employment outcomes

| Early intervention programmes providing supported employment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Year | Location | Design | Follow-up period | Sample size (follow-up) | Sample retention | Age (Baseline) | Outcome | Main finding |

| Early Intervention Programs Providing Supported Employment | |||||||||

| Porteous | 2007 | New Zealand | One-group prospective (two cohorts) | Up to 24 months | C1: 110 C2: 125 | C1:14–27 C2:15–26 | emp rate | See Table 2 and Fig. 2 | |

| Porteous | 2009 | New Zealand | One-group prospective | Up to 24 months | 135 | 14–26 | emp rate | ||

| Rinaldi | 2004 | UK | One-group prospective | 6 months | 40 | 18–32 | emp rate | ||

| Rinaldi | 2010b | UK | One-group prospective | 12 months | 142 | 17–32 | emp rate | ||

| Killackey | 2008 | Australia | RCT | 6 months | SE: 20 C: 21 | 100.0% | 15–25 | emp rate | |

| Killackey | 2012 | Australia | RCT | 6 months | SE: 67 C: 59 | 86.3% | Mn: 20.2 | emp rate | |

| Major | 2010 | UK | Quasi-exp | 12 months | SE: 44 C: 70 | 91.2% | 17–34 | emp rate | |

| Nuechterlein | 2014 | USA | RCT | 18 months | SE: 36 C: 15 | 73.9% | 18–45 | emp rate | |

| Dudley | 2014 | UK | Cross-sectional series | Up to 1 year | SE: 104 C: 90 | N/A | Mn = 24.2 (SE)/25.3 (C) | Employment and education | No differences on employment; SE had higher education rate |

| Fowler | 2009 | UK | Historical control | 24 months | Baseline: SE: 102 C: 69 | 84–96% | Mn = 22.0 (SE)/24.7 (C) | 15 h/week in paid work or education | SE: 44% C: 15%, p<0.05 |

| Singh | 2007 | UK | One-group prospective | 1 year | 121 | Mn = 22.8 | Employment or education | Increased from 29 to 42% | |

| Early Intervention Programs Providing Nonstandardized Vocational Assistance | |||||||||

| Abdel-Baki | 2013 | Canada | One-group prospective | 4 years | 66 | N/A | Mn = 23.5 | Work or school | Increase from 47 to 70% |

| Kelly | 2009 | UK | Retrospective survey | Not stated | 30 | 30% response rate | 14–35 | Self-report work or school | 57% |

| Parlato | 1999 | Australia | Retrospective survey | Not stated | 21 | N/A | 18–25 | Part-time employment | 19% |

| Poon | 2010 | Hong Kong | Retrospective survey | 3 months | 147 | N/A | 15–25 | 3 months in supported placement or comp emp | 27% |

| Garety | 2006 | UK | RCT | 18 months | EI: 67 C: 65 | 91.7% | Mn = 26 | 6 months in FT work or school | EI: 49% C: 29%, p<0.05 |

| Early Intervention Programs Without an Identified Vocational Component | |||||||||

| Henry | 2010 | Australia | One-group prospective | 7 years | 456 | 90.0% | Mn = 21.7 | emp PT or FT at follow-up | 39% employed |

| Agius | 2007 | UK | Quasi-experimental | 3 years | EI = 40 C = 40 | N/A | 14–35 | In work or school | EI: 65%* C: 48% |

| Bertelsen | 2008 | Denmark | RCT | 5 years | EI = 275 C = 272 | 100% (nat registry) | Mn = 26.6 | Working or in school | EI: 42% C: 46% |

| Chen | 2011 | Hong Kong | Historical control | 3 years | EI = 700 C = 700 | N/A | 15–25 | FT emp >6 months | EI: 64%* C: 48% |

| Cullberg | 2006 | Sweden | Historical control | 3 years | EI = 60 C = 41 | 88.6% | Mn = 27.7 (EI)/29.3 (C) | Working or in school | EI: 51% C: 49% |

| Eack | 2011 | USA | RCT | 2 years | EI = 24 C = 22 | 79.3% | Mn = 25.9 | Competitive emp at 2 years | EI: 54%* C: 18% |

| Hegelstad | 2012 | Norway | Quasi-experimental | 10 years | EI = 101 C = 73 | 61.9% | 18–65 | FT emp | EI: 28%* C: 11% |

| Mihalopoulos | 2009 | Australia | Matched historical control | Approx. 8 years | EI = 32 C = 33 | 63.7% | 14–30 | Any paid emp in last 2 years | EI: 56%* C: 33% |

| Bechdolf | 2007 | Germany | RCT | 12 months | EI = 29 C = 38 | 59.3% | Mn = 25.2 (EI)/26.4 (C) | SAS II work subscale | No difference |

| Fowler | 2009 | UK | RCT | 9 months | EI = 33 C = 38 | 92.2% | Mn = 27.8 (EI)/30.0 (C) | SOFAS | No difference |

| Macneil | 2012 | Australia | Matched controls | 18 months | EI = 20 C = 20 | 92.5% | Mn = 21.8 (EI)/21.3 (C) | SOFAS | EI > C |

| Penn | 2011 | USA | RCT | 3 months | EI = 22 C = 22 | 95.7% | Mn = 22 | RFS work subscale | EI > C |

*EI significantly higher than C.

EI, early intervention programme; SE, supported employment; nat, national; Mn, mean; C, control; emp, employment; PT, part time; FT, full time; SOFAS, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; SAS II, Social Adjustment Scale II; RFS, Role Functioning Scale.

The uncontrolled studies of early intervention programmes offering supported employment were naturalistic programme evaluations of ongoing service provision with a rolling enrolment and a shrinking sample over time. For two studies (Rinaldi et al. 2004, 2010b), we inspected sample sizes for different follow-up periods and chose the time frame that fairly reflected the outcomes while maintaining a reasonably large sample size. In two other studies (Porteous & Waghorn, 2007, 2009), the authors did not have a fixed follow-up period (Geoff Waghorn, personal communication, 2013). We reported their follow-up as ‘up to 24 months.’

Employment and education outcomes

In Table 2 we report employment and education rates at baseline and during follow-up for eight studies of early intervention programmes providing supported employment. Overall, 709 patients received supported employment and 165 patients received early intervention services excluding supported employment. The employment rate during follow-up for the supported employment patients was 49%, compared with 29% for the control patients, χ2 (1) = 21.6, p < 0.0001, ES = 0.41. Adjusting for the rate of employment among patients at programme admission, the increased employment rate from baseline to follow-up was 41% for supported employment and 17% for controls, ES = 0.54.

Table 2.

Employment and education outcomes in SE studies with early psychosis clients

| Primary author | Year of publication | N | % Competitively employed during follow-up | Estimated increase from baseline (employment) | % Education enrolments during follow-up | Estimated increase from baseline (education) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-post evaluations without comparison groups | ||||||

| Rinaldi | 2004 | 40 | 28% | 18% | 33% | 0% |

| Rinaldi | 2010b | 142 | 44% | 31% | 28% | 3% |

| Porteous | 2007 | 100 | Cohort 1: 36% | 36% | 13% | 13% |

| Porteous | 2009 | 125 | Cohort 2: 59% | 59% | 16% | 16% |

| 135 | 47% | 47% | 21% | 21% | ||

| Quasi-experimental evaluation | ||||||

| Major | 2009 | SE: 44 Ctl:70 | SE: 36% Ctl: 19% | SE: 23% Ctl: 5% | SE: 20% Ctl: 24% | SE: 6% Control: 7% |

| Randomised controlled trials | ||||||

| Killackey | 2008 | SE: 20 Ctl: 21 | SE: 65% Ctl: 10% | SE: 60% Ctl: 0% | SE: 35% Ctl: 24% | SE: 35% Ctl: 24% |

| Killackey | 2012 | SE: 67 Ctl: 59 | SE: 72% Ctl: 48% | SE: 50% Ctl: 37% | SE: 54% Ctl: 41% | SE: 38% Ctl: 22% |

| Nuechterlein | submitted | SE: 36 Ctl: 15 | SE: 69% Ctl: 33% | SE: 45% Ctl: 16% | SE: 67% Ctl: 53% | SE: 41% Ctl: 44% |

| Total (all studies) | SE | 709 | 49% | 41% | 27% | 11% |

| Ctl | 165 | 29% | 17% | 33% | 15% | |

| Effect size | 0.41 | 0.54 | −0.13 | −0.12 | ||

| χ2 (1) = 21.6, p < 0.0001 | χ2 (1) = 2.3, n.s. | |||||

SE, supported employment; Ctl, control group.

The enrolment rate in education during follow-up was 27% for supported employment participants compared with 33% of patients receiving usual services, χ2 (1) = 2.3, n.s., ES = −0.13. The increase in education enrolment rate over baseline for supported employment participants was 11% compared with 15% for patients receiving usual services, ES = −0.12.

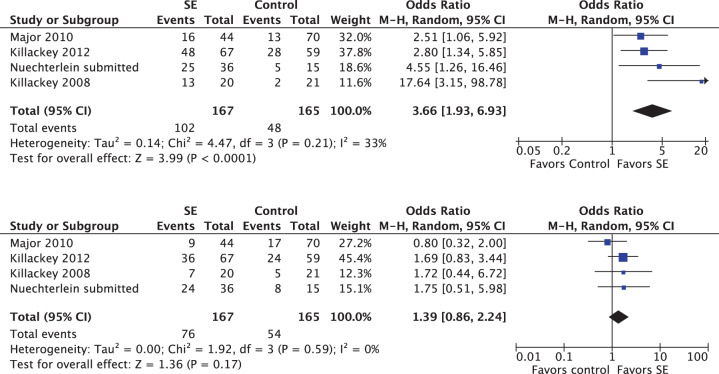

A meta-analysis on follow-up employment rates for four studies included 167 patients receiving supported employment and 165 patients receiving usual services (early intervention clinical services without supported employment), yielding a significant overall odds ratio of 3.66 [1.93–6.93], p < 0.0001, as shown in Fig. 2a. The test for heterogeneity was not significant (χ2 = 4.47, p < 0.21). The four studies each had significant odds ratios for employment outcomes favouring the supported employment condition. Meta-analysis on the increase in employment rate over baseline also significantly favoured the supported employment group 4.97 [1.53–16.22], p < 0.008 (figure not shown). The meta-analytic results for follow-up rates of education for these same studies yielded an odds ratio of 1.39 [0.86–2.24], p = 0.17, as shown in Fig. 2b. None of the studies found a significant difference between the supported employment and control conditions on enrolment in education.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for controlled and quasi-experimental studies of supported employment (SE).

Three studies using a combined measure of employment and education included a quasi-experimental study comparing an early intervention programme with a supported employment component to historical control participants who received usual community mental health treatment without supported employment. In the first, 44% of the early intervention group and 15% of the control group achieved ‘full functional recovery,’ defined as either 15 h per week in paid work or full-time student at 2-year follow-up (Fowler et al. 2009a). A second was an evaluation of an early intervention team providing supported employment that found that the rate employed or in education significantly increased from 29% at baseline to 42% at 1-year follow-up (Singh et al. 2007). A third study compared two early intervention programmes, one providing supported employment and the other not (Dudley et al. 2014). At 12 months, a measure of any vocational or educational activity significantly favoured the programme providing supported employment. However, because the authors did not follow fixed cohorts, the findings are difficult to evaluate.

After this paper was accepted for publication, another relevant study was published online ahead of print (Craig et al. 2014). Although the study focus was motivational interviewing, the authors reported a 31% paid employment rate during 12-month follow-up for 134 patients served by four early intervention teams providing IPS services. If we include these data in calculating the overall employment rate for early intervention programmes providing supported employment, the overall rate decreases from 49 to 46%.

Methodological characteristics of the supported employment studies

Of the four studies included in the meta-analysis, three were randomised controlled trials (Killackey et al. 2008, 2012; Nuechterlein et al. submitted for publication). One used a naturalistic design comparing early intervention programmes in two jurisdictions, only one staffed with an employment specialist (Major et al. 2010).

Variability in sampling can be seen across studies, as shown in Table 1. The studies differed substantially in the age eligibility criteria. In most studies, some participants were employed at the time of programme enrolment, thereby complicating the interpretation of employment outcomes. An admission criterion for two programmes was that patients had a goal of competitive employment (Porteous & Waghorn, 2007, 2009; Geoff Waghorn, personal communication, email, 2013), while in two other projects, all the patients had a goal to either get a job or complete their education (Rinaldi et al. 2004, Rinaldi et al. 2010b) (Miles Rinaldi, personal communication, 2013). The Major et al. (2010) study appears to have offered employment services to all patients who were enroled in an early intervention programme regardless of interest in employment. Nuechterlein et al. (submitted for publication) excluded patients with significant substance abuse and required an initial period of clinical stabilisation period before enrolment.

As group, strength of these evaluations was attention to model fidelity. All but one of the eight studies identified in Table 1 was explicitly modelled after IPS. The exception was the Major et al. (2010) study, which adopted many IPS principles without overtly labelling their services as IPS. The remaining studies all monitored services using the supported employment fidelity scale (Bond et al. 1997). Nevertheless, several projects also made adaptations either tailored to the population or to funding requirements. Most offered educational assistance, but did not follow a standardised supported education protocol. The supported employment programme in the Nuechterlein et al. (submitted for publication) study augmented their IPS services with a vocational skills training group. Because of funding restrictions, the two Australian studies (Killackey et al. 2008, 2012) limited IPS services to 6 months, a departure from the IPS model.

Early intervention programmes providing unspecified vocational assistance

As shown in Table 1, we identified five evaluations of early intervention programmes offering unspecified vocational services, classified as such by the absence of any clear suggestion of the intent to follow a specific vocational model (Parlato et al. 1999; Garety et al. 2006; Kelly et al. 2009; Poon et al. 2010; Abdel-Baki et al. 2013). Four were rudimentary programme evaluations with results that were difficult to evaluate. One was a randomised controlled trial reporting significant differences on a combined measure of employment and education favouring the programme with vocational services.

Early intervention programmes without formal vocational assistance

Twelve studies evaluating early intervention programmes without formal vocational assistance included eight reporting either a measure of employment outcome (Mihalopoulos et al. 2009; Henry et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2011; Eack et al. 2011; Hegelstad et al. 2012) or a combined measure of employment and education (Cullberg et al. 2006; Agius et al. 2007; Bertelsen et al. 2008). Four others reported changes on occupational functioning scales (Bechdolf et al. 2007; Fowler et al. 2009b; Penn et al. 2011; Macneil et al. 2012), as shown in Table 1.

Most controlled and quasi-controlled studies used treatment-as-usual control groups, which were usually less intensive services not tailored specifically to early psychosis. Such control groups were described as ‘standard’ or ‘generic’ community mental health treatment (Cullberg et al. 2006; Agius et al. 2007; Bertelsen et al. 2008; Mihalopoulos et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2011; Macneil et al. 2012). Other control groups were described as ‘enriched supportive therapy’ (Eack et al. 2011), ‘usual methods of detection of psychosis’ (Hegelstad et al. 2012), supportive counselling (Bechdolf et al. 2007), multidisciplinary case management (Fowler et al. 2009b), and a comprehensive, multi-element clinic for the treatment of psychosis (Penn et al. 2011). Methodological limitations were common in these studies, including uncertain equivalence between treatment groups. The sample retention rates ranged from 62 to 100%. The studies ranged in follow-up period from 2 to 10 years, all but one with a follow-up period of 3 years or more. Another limitation was the variability across study in the outcome measure used (e.g., time employed, full-time employment). Most studies identified employment as a secondary outcome measure, with clinical outcomes primary.

Of the seven studies with comparison groups reporting employment or employment/education rates at follow-up, five had significant results favouring early intervention services over usual services. We did not conduct meta-analysis on these studies, concluding that the results would be uninterpretable, given the great variability in measures used. For the same reasons, it was infeasible to calculate a meaningful overall employment rate or employment/education rate for this group of studies. Two of four studies examining changes in standardised occupational scales had significant results favouring early intervention services over usual services. One study with non-significant findings used a control group receiving some supported employment services, confounding the results (Fowler et al. 2009b). Aggregating the findings for all 11 studies with comparison groups, seven (64%) reported significant vocational/education outcomes favouring early intervention over usual services.

Discussion

This review found that incorporating well-defined evidence-based supported employment services into comprehensive early intervention programmes for patients in early psychosis significantly increases employment rates but does not improve educational outcomes compared with programmes lacking these services. About half of all patients in the programmes offering supported employment obtain competitive jobs during follow-up compared with 29% of those receiving supported employment. Although the number of studies was small, the findings for effectiveness of supported employment were consistently positive. By contrast, we cannot draw any conclusions about the effectiveness of unspecified vocational services in early intervention programmes, given the small and descriptive literature in this area.

The third type of study examined in this review evaluated specialty early intervention services v. generic, usually less intensive, community treatment. These studies hypothesised that specialised clinical care for early psychosis would promote vocational recovery, even absent specific vocational services. This hypothesis resembles the assumption held historically by many clinicians and researchers in the psychiatric field that helping patients with severe mental illness address psychiatric symptoms through medications and psychotherapy would enable them to pursue vocational rehabilitation and to gain employment – an assumption that proved false (Bond, 1992). In the current review, the parallel evidence regarding early intervention programmes without an identified vocational component was inconclusive because of the huge variability in measures of employment/educational outcome. The majority of studies did find significant improvement in functional outcome for early intervention patients compared with those in usual services, usually measured over a period of years. Confounding this overall finding, however, are methodological weaknesses in this heterogeneous group of studies.

Even assuming that we were to give the most generous interpretation of the findings from the studies of the early intervention programmes without identified vocational services, the control conditions for these studies were mostly generic mental health treatment services, which were not tailored specifically to patients with early psychosis. Also unknown is the extent to which control patients received these services rather than dropped out.

By contrast, the control groups in the supported employment studies were much more stringent, examining the added effects of supported employment for patients who were all receiving early intervention services. We conclude that the impact on employment of adding supported employment to early intervention programmes is larger than that for early intervention programmes compared with usual services.

While adding supported employment services to an early intervention programme leads to better competitive employment outcomes, the ES is moderate for the difference in employment rates at follow-up compared with services as usual. Furthermore, the overall competitive employment rate at follow-up in this review of 49% for young adults receiving supported employment is less than the overall rate of 59% in a review of 15 controlled trials of IPS for adults with severe mental illness (Bond et al. 2012b). It would be important to understand the reasons for this apparent diminished impact of supported employment for the early psychosis population.

Several interpretations are possible: First, people with early psychosis may be less responsive to evidence-based employment interventions than adults with longer-term illnesses. This conclusion seems unlikely, given a meta-analysis showing that young adults benefit from IPS as much, if not more, than older adults (Bond et al. in press). Second, some patients with early psychosis may prioritise education over employment, thereby diluting the employment rate. Third, the early intervention studies reviewed above may not have implemented IPS supported employment with high fidelity or followed patients long enough, given that some patients initially pursued education.

The field needs longer-term and more rigorous studies of employment services within early psychosis programmes. The lack of findings for educational outcomes surprises, given the importance of educational goals in this age group, but the field lacks an evidence-based model of supported education. Researchers also should track disability benefits status, although these vary tremendously from country to country.

The cost implications of increasing employment through supported employment in early intervention programmes are enormous because young people with psychotic illnesses tend to remain disabled for decades. Worldwide, people with serious mental illnesses constitute the largest and fastest-growing group of disability beneficiaries (McAlpine & Warner, 2000; Danziger et al. 2009). Many experts recommend refocusing policy on preventing entry to disability programmes rather than on promoting exits from these programmes (Burkhauser & Daly, 2011). Observational studies suggest that, after initial episodes of psychosis, young adults who join or remain in the labour market are more likely to forestall entry into the disability system (Cougnard et al. 2007; Krupa et al. 2012; Drake et al. 2013). Two evaluations aimed at diverting new applicants for disability benefits through early interventions incorporating employment services had disappointing results (Fraker, 2013; Gimm et al. 2014), but neither study used an evidence-based employment model.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. First, although it is the most comprehensive and rigorous to date, it did not meet the full standards of a PRISMA review (Moher et al. 2009). For example, we did not examine publication bias or method of concealment for randomised trials, nor did we exhaustively search the grey literature. Second, study quality was highly variable. The supported employment studies were small with short follow-ups. The effects on the population and the long-term effects of supported employment interventions are almost entirely unknown. Third, with the exception of supported employment, which was usually well described and systematically monitored with a fidelity scale, many papers lacked adequate descriptions of their interventions. This deficiency is widespread in the intervention literature (Michie et al. 2009). Fourth, the study methodologies were heterogeneous, using diverse measures, observational periods, and data collection procedures. The lack of methodological consistency across studies included in this review is striking and in sharp contrast to the consensus among IPS researchers on methodological standards for evaluation studies (Marshall et al. 2014). Shared standards permit comparisons across studies and meta-analytic syntheses. Future early intervention studies should include a comprehensive set of employment measures, including job duration, earnings and time to first job (Bond et al. 2012a). Fifth, the use of inferential statistics to evaluate differences between combined treatment and control conditions should be interpreted with caution, given multiple threats to validity, including selection and sampling biases.

Conclusions

Early intervention researchers recognise the need to include vocational interventions in programmes for early episode patients, and are now explicitly identifying IPS as the preferred model (Nordentoft et al. 2013). This review provides additional support for this recommendation. The potential of these programmes to reduce participation in disability programmes remains unclear.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- Abdel-Baki A, Létourneau G, Morin C, Ng A (2013). Resumption of work or studies after first-episode psychosis: the impact of vocational case management. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 7, 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington D, McKenzie E, Norman R, Wang JL, Bond GR (2013). Identification of essential evidence-based components of first episode psychosis services. Psychiatric Services 64, 452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agius M, Shah S, Ramkisson R, Murphy S, Zaman R (2007). Three year outcomes of an early intervention for psychosis service as compared with treatment as usual for first psychotic episodes in a standard community mental health team. Preliminary results. Psychiatria Danubina 19, 10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett J, Lloyd C (2001). Work issues for young people with psychosis: barriers to employment. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 64, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Veith V, Ruhrmann S, Pukrop R, Brockhaus-Dumke A, Berning J, Stamm E, Janssen B, Decker P, Bottlender R, Moller H, Gaebel W, Maier W, Klosterkotter J (2007). Randomized controlled multicentre trial of cognitive behaviour therapy in the early initial prodromal state: effects on social adjustment post treatment. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 1, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Øhlenschlæger J, Le Quach P, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M (2008). Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 65, 762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR (1992). Vocational rehabilitation. In Handbook of Psychiatric Rehabilitation (ed. Liberman R.P.), Macmillan: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, Vogler KM (1997). A fidelity scale for the Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 40, 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE (2011). Measurement of fidelity of implementation of evidence-based practices: case example of the IPS Fidelity Scale. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 18, 126–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Campbell K, Drake RE (2012a). Standardizing measures in four domains of employment outcome for Individual Placement and Support. Psychiatric Services 63, 751–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR (2012b). Generalizability of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment outside the US. World Psychiatry 11, 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Campbell K (in press). Effectiveness of IPS supported employment for young adults. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne DJ, Waghorn G (2010). Employment services as an early intervention for young people with mental illness. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 4, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke-Miller J, Razzano LA, Grey DD, Blyler CR, Cook JA (2012). Supported employment outcomes for transition age youth and young adults. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 35, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhauser RV, Daly M (2011). The Declining Work and Welfare of People with Disabilities: What Went Wrong and a Strategy for Change. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Caton CL, Drake RE, Hasin D, Dominguez B, Shrout PE, Samet S, Schanzer B (2005). Differences between early phase primary psychotic disorders with concurrent substance use and substance-induced psychoses. Archives of General Psychiatry 62, 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EY, Tang JY, Hui CL, Chiu CP, Lam MM, Law CW, Yew CW, Wong GH, Chung DW, Tso S, Chan KP, Yip KC, Hung SF, Honer WG (2011). Three-year outcome of phase-specific early intervention for first-episode psychosis: a cohort study in Hong Kong. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 5, 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton SM, Luxmoore M, Woodhead G, Albiston DD, Gleeson JF, McGorry PD (2011). Group programmes in early intervention services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 5, 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougnard A, Goumilloux R, Monello F, Verdoux H (2007). Time between schizophrenia onset and first request for disability status in France and associated patient characteristics. Psychiatric Services 58, 1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig T, Shepherd G, Rinaldi M, Smith J, Carr S, Preston F, Singh S (2014). Vocational rehabilitation in early psychosis: cluster randomised trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, online ahead of print May 22, 2014, doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullberg J, Mattsson M, Levander S, Holmqvist R, Tomsmark L, Elingfors C, Wieselgren IM (2006). Treatment costs and clinical outcome for first episode schizophrenia patients: a 3-year follow-up of the Swedish ‘Parachute Project’ and two comparison groups. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 114, 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danziger S, Frank RG, Meara E (2009). Mental illness, work, and income support programs. American Journal of Psychiatry 166, 398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Bond GR, Becker DR (2012). Individual Placement and Support: An Evidence-Based Approach to Supported Employment. Oxford University Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Xie H, Bond GR, McHugo GJ, Caton CL (2013). Early psychosis and employment. Schizophrenia Research 146, 111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley R, Nicholson M, Stott P, Spoors G (2014). Improving vocational outcomes of service users in an early intervention in psychosis service. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 8, 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS (2011). Effects of cognitive enhancement therapy on employment outcomes in early schizophrenia: results from a 2-Year Randomized trial. Research on Social Work Practice 21, 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KM, Xie B, Glynn SM (2012). Adapting the individual placement and support model with homeless young adults. Child and Youth Care Forum 41, 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Howells L, Millward M, Ivins A, Taylor G, Hackmann C, Hill K, Bishop N, MacMillan I (2009a). Can targeted early intervention improve functional recovery in psychosis? A historical control evaluation of the effectiveness of different models of early intervention service provision in Norfolk 1998–2007. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 3, 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Painter M, Reilly T, Crane C, MacMillan I, Mugford M, Croudace T, Jones PB (2009b). Cognitive behaviour therapy for improving social recovery in psychosis: a report from the ISREP MRC Trial Platform study (improving social recovery in early psychosis). Psychological Medicine 39, 1627–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker T (2013). The Youth Transition Demonstration: lifting employment barriers for youth with disabilities. Mathematica Policy Research Issue Brief, February 2013, 13–01.

- Garety PA, Craig TK, Dunn G, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Colbert S, Rahaman N, Read J, Power P (2006). Specialised care for early psychosis: symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction: randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 188, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimm G, Hoffman D, Ireys HT (2014). Early interventions to prevent disability for workers with mental health conditions: impacts from the DMIE. Disability and Health Journal 7, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B, Evensen J, Haahr U, Joa I, Johannesen JO, Langeveld J, Melle I, Opjordsmoen S, Rossberg JI, Rund BR, Simonsen E, Sundet K, Vaglum P, Friis S, McGlashan T (2012). Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry 169, 374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, Yuen HP, Harrigan SM, Prosser AL, Schwartz OS, Farrelly SE, Herrman H, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2010). The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 71, 716–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes F, Stavely H, Simpson R, Goldstone S, Pennell K, McGorry P (2014). At the heart of an early psychosis centre: the core components of the 2014 Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre model for Australian communities. Australasian Psychiatry 22, 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer SN, Mangala R, Anitha J, Thara R, Malla AK (2011). An examination of patient-identified goals for treatment in a first-episode programme in Chennai, India. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 5, 360–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J, Wellman N, Sin J (2009). HEART – the Hounslow Early Active Recovery Team: implementing an inclusive strength-based model of care for people with early psychosis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 16, 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey EJ, Jackson HJ, Gleeson J, Hickie IB, McGorry PD (2006). Exciting career opportunity beckons! Early intervention and vocational rehabilitation in first-episode psychosis: employing cautious optimism. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40, 951–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey EJ, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD (2008). Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. British Journal of Psychiatry 193, 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killackey EJ, Allott KA, Cotton SM, Chinnery GL, Sun P, Collins Z, Massey J, Baksheev G, Jackson HJ (2012). Vocational recovery in first episode psychosis: first results from a large controlled trial of IPS. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 6, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Krupa T, Oyewumi K, Archie S, Lawson JS, Nandlal J, Conrad G (2012). Early intervention services for psychosis and time until application for disability income support: a survival analysis. Community Mental Health Journal 48, 535–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW (1990). Design Sensitivity. Sage: Newbury Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil CA, Hasty M, Cotton S, Berk M, Hallam K, Kader L, McGorry P, Conus P (2012). Can a targeted psychological intervention be effective for young people following a first manic episode? Results from an 18-month pilot study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 6, 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major BS, Hinton MF, Flint A, Chalmers-Brown A, McLoughlin K, Johnson S (2010). Evidence of the effectiveness of a specialist vocational intervention following first episode psychosis: a naturalistic prospective cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 45, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malla AK, Norman RM, Joober R (2005). First-episode psychosis, early intervention, and outcome: what have we learned? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50, 881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T, Goldberg RW, Braude L, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, George P, Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014). Supported employment: assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services 65, 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine DD, Warner L (2000). Barriers to Employment among Persons with Mental Illness: A Review of the Literature. Center for Research on the Organization and Financing of Care for the Severely Mentally Ill Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research Rutgers, the State University: New Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, Jackson HJ (1996). EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22, 305–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Killackey E, Yung AR (2008). Early intervention in psychosis: concepts, evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry 7, 148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Fixsen D, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP (2009). Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interventions: the need for a scientific method. Implementation Science, 4, doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalopoulos C, Harris M, Henry L, Harrigan S, McGorry P (2009). Is early intervention in psychosis cost-effective over the long term? Schizophrenia Bulletin 35, 909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The Prisma Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. British Medical Journal 339, b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordentoft M, Melau M, Iversen T, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, Bertelsen M, Hjorthøj CR, Hastrup LH, Jørgensen P (2013). From research to practice: how OPUS treatment was accepted and implemented throughout Denmark. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, DOI: 10.1111/eip.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Turner LR, Ventura J, Becker DR, Drake RE (2008). Individual Placement and Support for individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia: Integrating supported education and supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31, 340–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Ventura J, Turner LR, Gitlin MJ, Gretchen-Doorly D, Becker DR, Drake RE, Wallace CJ, Liberman RP (submitted for publication). Successful return to work or school after a first episode of schizophrenia: the UCLA randomized controlled trial of Individual Placement and Support and workplace fundamentals module training. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parlato L, Lloyd C, Bassett J (1999). Young Occupations Unlimited: an early intervention programme for young people with psychosis. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 62, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Uzenoff SR, Perkins D, Mueser KT, Hamer R, Waldheter E, Saade S, Cook L (2011). A pilot investigation of the Graduated Recovery Intervention Program (GRIP) for first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 125, 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon MY, Siu AM, Ming SY (2010). Outcome analysis of occupational therapy programme for persons with early psychosis. Work 37, 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteous N, Waghorn G (2007). Implementing evidence-based employment services in New Zealand for young adults with psychosis: progress during the first five years. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 70, 521–526. [Google Scholar]

- Porteous N, Waghorn G (2009). Developing evidence-based supported employment services for young adults receiving public mental health services [online]. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy 59, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay CE, Broussard B, Goulding SM, Cristofaro S, Hall D, Kaslow NJ, Killackey E, Penn D, Compton MT (2011). Life and treatment goals of individuals hospitalized for first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Psychiatry Research 189, 344–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RevMan (2012). Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.2. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration: Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi M, McNeil K, Firn M, Koletsi M, Perkins R, Singh SP (2004). What are the benefits of evidence-based supported employment for patients with first-episode psychosis? Psychiatric Bulletin 28, 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi M, Killackey E, Smith J, Shepherd G, Singh S, Craig T (2010a). First episode psychosis and employment: a review. International Review of Psychiatry 22, 148–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi M, Perkins R, McNeil K, Hickman N, Singh SP (2010b). The Individual Placement and Support approach to vocational rehabilitation for young people with first episode psychosis in the UK. Journal of Mental Health 6, 483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Grange T, Vijaykrishnan A, Francis S, White S, Fisher H, Chisholm B, Firn M (2007). One-year outcome of an early intervention in psychosis service: a naturalistic evaluation. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 1, 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Skalli L, Nicole L (2011). Specialised first-episode psychosis services: a systematic review of the literature. [Article in French]. Encephale 37, S66–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR (2012). Early intervention in psychosis: evidence, evidence gaps, criticism, and confusion. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 46, 7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]