Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Infarct volume is an important predictor of clinical outcome in acute stroke. We hypothesized that the association of infarct volume and clinical outcome changes with the magnitude of infarct size.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Data were derived from the Safety and Efficacy of Nerinetide in Subjects Undergoing Endovascular Thrombectomy for Stroke (ESCAPE-NA1) trial, in which patients with acute stroke with large-vessel occlusion were randomized to endovascular treatment plus either nerinetide or a placebo. Infarct volume was manually segmented on 24-hour noncontrast CT or DWI. The relationship between infarct volume and good outcome, defined as mRS 0–2 at 90 days, was plotted. Patients were categorized on the basis of visual grouping at the curve shoulders of the infarct volume/outcome plot. The relationship between infarct volume and adjusted probability of good outcome was fitted with linear or polynomial functions as appropriate in each group.

RESULTS:

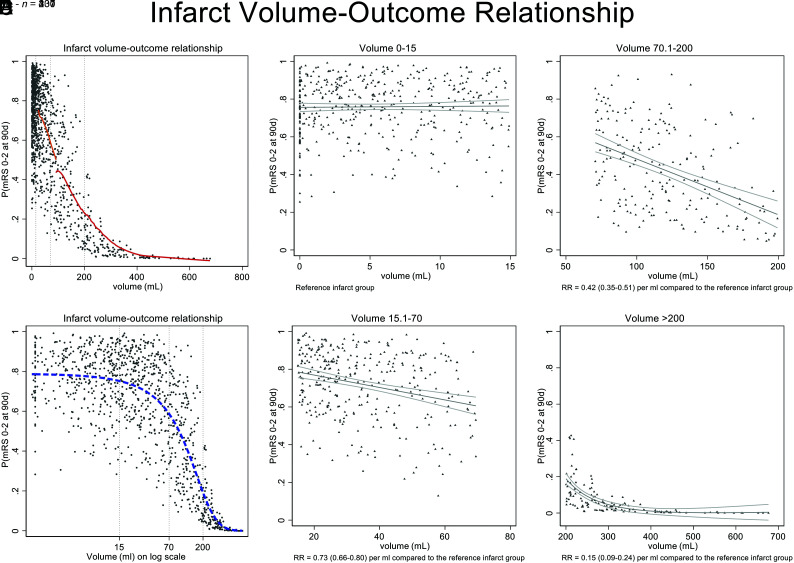

We included 1099 individuals in the study. Median infarct volume at 24 hours was 24.9 mL (interquartile range [IQR] = 6.6–92.2 mL). On the basis of the infarct volume/outcome plot, 4 infarct volume groups were defined (IQR = 0–15 mL, 15.1–70 mL, 70.1–200 mL, >200 mL). Proportions of good outcome in the 4 groups were 359/431 (83.3%), 219/337 (65.0%), 71/201 (35.3%), and 16/130 (12.3%), respectively. In small infarcts (IQR = 0–15 mL), no relationship with outcome was appreciated. In patients with intermediate infarct volume (IQR = 15–200 mL), there was progressive importance of volume as an outcome predictor. In infarcts of > 200 mL, outcomes were overall poor.

CONCLUSIONS:

The relationship between infarct volume and clinical outcome varies nonlinearly with the magnitude of infarct size. Infarct volume was linearly associated with decreased chances of achieving good outcome in patients with moderate-to-large infarcts, but not in those with small infarcts. In very large infarcts, a near-deterministic association with poor outcome was seen.

In acute ischemic stroke, the larger the irreversibly damaged area is, the more severe and permanent the clinical deficits will be. Infarct size is predictive of clinical outcome in acute ischemic stroke1 and has been used as a surrogate outcome in several studies.2 However, human brain architecture leads to an exquisite structure-function relationship so that even small lesions may cause specific disability. As a corollary, recent studies have shown that the correlation between infarct volume and clinical outcome is only moderate.3,4 Anterior choroidal infarcts, for example, are very small but frequently lead to severe disability due to the specific structures damaged.5 We explored the relationship between infarct volume and outcome, hypothesizing that the association of infarct volume and clinical outcome is nonlinear and varies by the magnitude of infarct size.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

Data are from the Safety and Efficacy of Nerinetide in Subjects Undergoing Endovascular Thrombectomy for Stroke (ESCAPE-NA1) trial, a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of the neuroprotectant nerinetide6 in patients with acute ischemic stroke who underwent endovascular treatment. Patients were randomized to a single, 2.6-mg/kg dose of intravenous nerinetide or a placebo. All patients received endovascular treatment and best medical care, including intravenous alteplase if indicated. Noncontrast CT and multiphase CTA7 at baseline were performed in all patients. Patients were eligible for the trial only if they had a large-vessel occlusion (intracranial internal carotid artery, M1 occlusion or functional M1 occlusion [occlusion of both M2 branches]), moderate or good collaterals (defined as filling of ≥50% of the middle cerebral artery territory), and an ASPECTS of ≥5. The remaining inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) 18 years of age or older, 2) baseline NIHSS score >5, functional independence before the ischemic stroke (Barthel Index score >90), and 3) time since last known well <12 hours.

Image Analysis

All imaging data (baseline noncontrast CT and multiphase CTA, conventional angiography, follow-up noncontrast CT, and DWI) were reviewed in consensus readings by an independent core lab that was blinded to clinical outcomes. Final infarct volumes were measured by summation of the manual planimetric demarcation of the infarct on axial NCCT or diffusion-weighted MR imaging at 24 hours using the open-source software ITK-SNAP (http://www.itksnap.org).

Outcomes of Interest

The primary outcome was good outcome, which was defined as an mRS 0–2 at 90 days. Additional outcomes were mRS 0–1 and mortality at 90 days.

Statistical Analysis

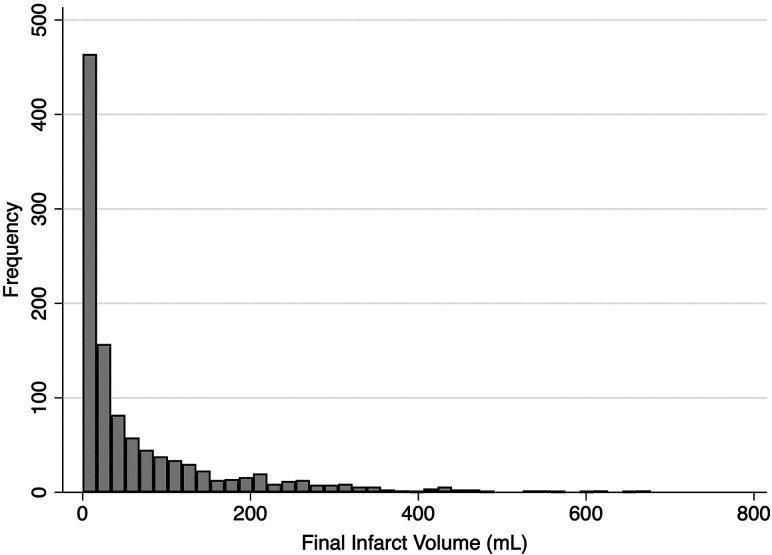

Because final infarct volume was not normally distributed (Fig 1), the relationship between infarct volume and good outcome was plotted with volume examined as a continuous variable, log-transformed in deciles, quartiles, and tertiles. On the basis of visual inspection, we defined final infarct volume groups at the curve shoulders of the infarct volume/outcome plot. Patient baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes were reported for each of the infarct volume groups. Adjusted probabilities of good outcome were obtained from a generalized linear model using a Poisson distribution with Huber-White robust sandwich variance estimation to allow direct estimation of risk ratios.8 The model was adjusted for a priori variables, including key treatment and pretreatment variables used in the minimization algorithm (age, sex, baseline NIHSS, ASPECTS, occlusion location, alteplase treatment, nerinetide treatment) as independent variables. We displayed the relationship between adjusted probability of good outcome, derived from the multivariable model, and infarct volume as a panel of plots showing volume as a continuous variable, log-transformed volume, and then by volume groups. The relationship between final infarct volume by volume group and the adjusted probability of good outcome was then fitted with a linear or polynomial function as appropriate. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and conventional levels of significance (α = .05) were used for interpretation. All analysis was performed using STATA 16.1 (StataCorp).

FIG 1.

Distribution of infarct volumes in the patient sample.

RESULTS

Infarct volume was available for 1099/1105 patients who were included in the analysis. Infarct volume was measured on CT (n = 652, 59.3%) and MR imaging (n = 447, 40.7%). Median infarct volume was 24.9 mL (IQR = 6.6–92.2 mL). Good functional outcome was achieved by 666/1105 (60.3%) at 90 days, while 147/1105 (13.3%) patients died within 90 days. On the basis of visual assessment of the infarct volume/outcome plot (Fig 2A, -B), 4 infarct volume groups were defined (0–15 mL, 15.1–70 mL, 70.1–200 mL, >200 mL). The Online Supplemental Data show patient baseline characteristics and workflow variables for the 4 groups. As expected, the ASPECTS was lower, and successful recanalization, less common in patients with larger infarcts. Clinical outcomes for the 4 groups are shown in the Table. When the relationship of infarct volume and the adjusted probability of good outcome was modelled in each infarct volume group, it became apparent at low volumes (group 1: IQR = 0–15 mL) that infarct volume had no clear relationship with outcome (Fig 2C). In volume groups 2 and 3 with volumes from 15 to 200 mL, there was progressive importance of volume as a predictor of outcome (Fig 2D, -E). When infarct volume was very large (group 4: >200 mL), the volume of infarct seemed to be the dominant factor in predicting outcome, and probabilities of achieving good outcome were generally very low (Fig 2F).

FIG 2.

Probability of mRS 0–2 at 90 days adjusted for infarct volume and key baseline variables (age, sex, NIHSS, ASPECTS, occlusion location, alteplase treatment, nerinetide treatment). A, Lines of best fit for volume groups 3 and 4, modelled within each volume group using a LOWESS function (red line). Lines of best fit are not shown for groups 1 and 2 because the volumes are so compressed by the x-axis scale. B, Volumes on a log scale better show the relationship at low infarct volumes (dashed blue line). Dashed vertical gray lines indicate curve shoulders that have been used to define infarct volume groups. C–F, Volume grouping according to visually-defined groupings at the curve shoulders. The graphs illustrate that at low volumes (IQR = 0–15 mL), the infarct volume has no relationship with outcome (C); other factors are deterministic of outcome. In volume groups 2 and 3 with volumes from 15 to 200 mL (D and E), there is progressive importance of volume as a predictor of outcome. At volumes of ≥200 mL (F), a large infarct volume is the determinant factor in predicting outcomes, which are generally poor. RR indicates risk ratio; 90d, ninety days; P, probability.

Clinical outcomes in each infarct volume group

| Variable | Infarct Volume 0–15 mL (n = 431) | Infarct Volume 15.1–70 mL (n = 337) | Infarct Volume 70.1–200 mL (n = 201) | Infarct Volume >200 mL (n = 130) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| mRS 0–2 at 90 days (No.) (%) | 359 (83.3) | 219 (65.0) | 71 (35.3) | 16 (12.3) |

| Additional outcomes | ||||

| mRS 0–1 at 90 days (No.) (%) | 269 (62.4) | 142 (42.1) | 31 (15.4) | 5 (3.8) |

| Mortality at 90 days (No.) (%) | 18 (4.2) | 26 (7.7) | 34 (16.9) | 64 (49.2) |

DISCUSSION

The relationship between infarct volume and clinical outcome varies nonlinearly with the magnitude of infarct size. In small infarcts, on average, volume did not predict clinical outcome, while in moderate-to-large infarcts, larger infarct volume was linearly associated with decreased chances of achieving good outcome. When infarcts were very large, there was a near-deterministic relationship with poor outcome. This nonlinear relationship and the widely scattered infarct volumes we observed suggest that reliable prediction of clinical outcome based on infarct volume is not feasible for individual patients.

In prior work using mediation analysis, reduction of infarct volume explains only roughly 10% of the treatment benefit of endovascular treatment,3 possibly because of confounding factors such as brain eloquence, infarct patterns (eg, white matter sparing infarcts9), and selective neuronal loss.10 This result might be particularly true when infarct volumes are small, in which case the location and eloquence of the affected tissue plays an even more critical role.

The result has relevant clinical and research implications. Infarct volume is often used as an imaging outcome in clinical trials.2 However, the association with clinical outcome is imperfect and of limited value for individual outcome prediction.4 Clinically, small infarct volumes measured at 24 hours poststroke can be considered as directly related to patient selection and treatment success. If a small infarct volume is achieved, then outcome will be determined, not by the infarct, but by complications in the follow-up period, meaning that attention to stroke unit care, stroke work-up, and prevention posttreatment will be deterministic in outcome.11 Furthermore, involvement of certain anatomic structures and the eloquence of the affected brain parenchyma probably play a role in clinical outcome in patients with small infarcts. Those with very large infarcts have so much injury that postprocedural care, while important for compassionate and palliative goals of care, may simply not be substantially important in predicting good outcome. It will remain important clinically all across the patient spectrum to work quickly and obtain high-quality reperfusion to reduce infarct volumes. When infarcts are already very large (>200 mL) or if ASPECTS is very low (0–2), the prognosis may already be so poor that intervention is likely to be futile.

Use of infarct volume as a surrogate outcome can be refined on the basis of these data. Volume may only be a useful surrogate measure in the middle range of infarcts. Work on lesion-mapping with a goal of understanding structure-function relationships, similarly, may be useful only in smaller infarcts because of the floor effects on outcome associated with large infarcts.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study are its large and inclusive randomized patient sample, which resulted in a wide spectrum of infarct volumes, which were manually measured by an independent core lab. The study also has several limitations: Infarct volumetry on noncontrast head CT can be challenging, particularly because follow-up imaging was performed relatively early at 24 hours, a time at which infarcted tissue is often not yet sharply demarcated. Only patients with baseline ASPECTS of ≥5 were included in the ESCAPE-NA1 trial, and this feature might have limited the number of patients with very large infarcts, obscuring more detailed understanding of the relationship between very large infarcts and outcome. Neither NCCT nor DWI can distinguish between pan-necrosis and incomplete infarction;12 in other words, we cannot be sure that what we think of as “infarct” on imaging is indeed irreversibly injured tissue. Measurement inaccuracy is relatively higher in smaller infarcts.13 Last, this study was a post hoc study of a patient sample of the ESCAPE-NA1 rather than a prespecified analysis and, therefore, should be considered purely exploratory. Further prospective studies to confirm our findings are needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, the relationship between infarct volume and clinical outcome depends nonlinearly on the magnitude of infarct size. Within small and very large infarct groups, outcome does not vary by volume, but there is a linear relationship between larger volume and poorer outcome in moderate-sized infarcts. Our analysis further dissects and quantitates the volume-outcome relationship and provides direction on when infarct volume could be used as a surrogate outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are most grateful to all enrolling sites.

ABBREVIATION:

- IQR

interquartile range

Footnotes

The ESCAPE-NA1 trial was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, AB Innovates, and NoNO Inc.

Disclosures: Michael D. Hill—RELATED: Grant: NoNO Inc, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, AB Innovates, Comments: grants to the University of Calgary for the ESCAPE-NA1 trial*; UNRELATED: Board Membership: Circle NVI, Canadian Neuroscience Federation, Canadian Stroke Consortium; Consultancy: Boehringer Ingelheim; Grants/Grants Pending: Alberta Innovates, Canadian Institutes for Health Research, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Stryker, Medtronic, Biogen, Comments: grants to the University of Calgary*; Patents (Planned, Pending or Issued): US Patent office No. 62/086,077; Stock/Stock Options: Circle CVI, PureWeb Inc. Bijoy K. Menon—UNRELATED: Board Membership: Circle NVI; Patents (Planned, Pending or Issued): Systems of Triage in Acute Stroke; Stock/Stock Options: shares in Circle NVI. Andrew Demchuk—RELATED: Grant: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Comments: The ESCAPE-NA1 was funded and supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research*; Consulting Fee or Honorarium: Medtronic, Comments: I have received honoraria for consulting to Medtronic; UNRELATED: Employment: University of Calgary; Patents (Planned, Pending or Issued): Circle NVI; Stock/Stock Options: Circle NVI. Raul Nogueira—OTHER RELATIONSHIPS: consulting fees for advisory roles with Anaconda, Biogen, Cerenovus, Genentech, Imperative Care, Medtronic, phenox, Prolong Pharmaceuticals, and Stryker Neurovascular and stock options for advisory roles with Astrocyte, Brainomix, Cerebrotech, Ceretrieve, Corindus Vascular Robotics, Vesalio, Viz.ai, and Perfuze. Alexandre Poppe—UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: CAsTOR networking grant, Stryker. Diogo Haussen—UNRELATED: Consultancy: Stryker, Vesalio, Cerenovus; Stock/Stock Options: Viz.ai. Manish Joshi—UNRELATED: Employment: University of Calgary, Canada. Mahesh Jayaraman—UNRELATED: Payment for Lectures Including Service on Speakers Bureaus: Medtronic, Comments: payment for lecture at International Stroke Conference 2018. Mayank Goyal—RELATED: Grant: NoNO Inc, Comments: unrestricted research grant to University of Calgary for the ESCAPE-NA1 trial*; UNRELATED: Consultancy: Stryker, Medtronic, MicroVention, Mentice. Michael Tymianski—UNRELATED: Employment: NoNO Inc, Comments: Sponsor of ESCAPE-NA1; Stock/Stock Options: I own NoNO Inc stock; OTHER RELATIONSHIPS: I am CEO of NoNO Inc, the sponsor of the ESCAPE-NA1 trial. *Money paid to the Institution.

References

- 1.Al-Ajlan FS, Goyal M, Demchuk AM, et al. for the ESCAPE Trial Investigators. Intra-arterial therapy and post-treatment infarct volumes: insights from the ESCAPE randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2016;47:777–81 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaidi SF, Aghaebrahim A, Urra X, et al. Final infarct volume is a stronger predictor of outcome than recanalization in patients with proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion treated with endovascular therapy. Stroke 2012;43:3238–44 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.671594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boers AM, Jansen IG, Brown S, et al. Mediation of the relationship between endovascular therapy and functional outcome by follow-up infarct volume in patients with acute ischemic stroke. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:194–202 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boers AM, Jansen IG, Beenen LF, et al. Association of follow-up infarct volume with functional outcome in acute ischemic stroke: a pooled analysis of seven randomized trials. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:1137–42 10.1136/neurintsurg-2017-013724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hupperts RM, Lodder J, Heuts-van Raak EP, et al. Infarcts in the anterior choroidal artery territory: anatomical distribution, clinical syndromes, presumed pathogenesis and early outcome. Brain 1994;117:825–34 10.1093/brain/117.4.825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, et al. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor-PSD-95 protein interactions. Science 2002;298:846–50 10.1126/science.1072873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon BK, d'Esterre CD, Qazi EM, et al. Multiphase CT angiography: a new tool for the imaging triage of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Radiology 2015;275:510–20 10.1148/radiol.15142256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ospel JM, Singh N, Almekhlafi MA, et al. Early recanalization with alteplase in stroke because of large-vessel occlusion in the ESCAPE trial. Stroke 2021;52:304–07 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleine JF, Kaesmacher M, Wiestler B, et al. Tissue-selective salvage of the white matter by successful endovascular stroke therapy. Stroke 2017;48:2776–83 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron JC, Yamauchi H, Fujioka M, et al. Selective neuronal loss in ischemic stroke and cerebrovascular disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014;34:2–18 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganesh A, Menon BK, Assis ZA, et al. Discrepancy between post-treatment infarct volume and 90-day outcome in the ESCAPE randomized controlled trial. Int J Stroke 2020June9[Epub ahead of print] 10.1177/1747493020929943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia JH, Lassen NA, Weiller C, et al. Ischemic stroke and incomplete infarction. Stroke 1996;27:761–65 10.1161/01.STR.27.4.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ospel JJ, Schulze-Zaachau V, Kozerke S, et al. Spatial resolution and the magnitude of infarct volume measurement error in DWI in acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020;41:792–97 10.3174/ajnr.A6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]