Abstract

Purpose of review:

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) survivors frequently suffer significant, prolonged physical disability. ‘ICU Survivorship’, or addressing quality of life impairments post-ICU care, is a defining challenge, and existing standards of care fail to successfully address these disabilities. We suggest addressing persistent catabolism by treatment with testosterone analogs combined with structured exercise is a promising novel intervention to improve “ICU Survivorship”.

Recent Findings:

One explanation for lack of success in addressing post-ICU physical disability is most ICU patients exhibit severe testosterone deficiencies early in ICU that drives persistent catabolism despite rehabilitation efforts. Oxandrolone is an FDA-approved testosterone analogue for treating muscle weakness in ICU patients. A growing number of trials with this agent combined with strutured exercise show clinical benefit, including improved physical function and safety in burns and other catabolic states. However, no trials of oxandrolone/testosterone and exercise in non-burn ICU populations have been conducted.

Summary:

Critical illness leads to a catabolic state, including severe testosterone deficiency that persists throughout hospital stay, and results in persistent muscle weakness and physical dysfunction. The combination of an anabolic agent with adequate nutrition and structured exercise is likely essential to optimize muscle mass/strength and physical function in ICU survivors. Further research in ICU populations is needed.

Keywords: muscle, testosterone, oxandrolone, rehabilitation, critical illness

Introduction

Critical illness remains a major U.S. public health crisis. Critical illness currently affects 5.7 million Americans/year and every American can expect to average 1.7 intensive care unit (ICU) admissions in their lifetime (1). Cost savings of up to $1 billion/quality life-year gained can be achieved with improved management of ICU-related illness and disability (2). Innovations in ICU care resulted in yearly reductions in hospital mortality from sepsis (3), and recent data indicates >90% of ICU patients survive ICU stays. However, survival comes at a cost. ICU survivors frequently experience significant disabilities, commonly physical including muscle weakness and functional impairments that can persist for years (4-6). Muscle weakness in the ICU is associated with delayed liberation from ventilation, extended ICU and hospital stays, worse long-term survival and physical functioning and quality of life (4-7). These same data reveal many ICU “survivors” do not return home to functional lives following ICU care, but instead are discharged to rehabilitation settings where it is unclear if they ever return to a meaningful quality of life (6). Collectively, these impaired physical functions are defined as ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) or Post-ICU Syndrome (PICS)(6, 8)**. While we have improved therapies to increase the initial survival from critical illness, the challenge of optimizing recovery and survivorship after ICU care is yet to be meaningfully addressed.

Why is it essential to develop novel, innovative therapies for ICU-Acquired Weakness?

Critical illness is characterized by muscle catabolism with early onset through upregulation of proteolytic pathways (9) associated with systemic inflammatory conditions such as sepsis (10)* and pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with bedrest (11). This acute catabolic response leads to rapid loss of lean body mass, weakness, and loss of physical function (6)(12). ICU-AW is a clinical diagnosis made via manual muscle strength testing and is reported in 25 to 65% of patients (13). Catabolism, hypermetabolism, and muscle weakness, under current standard of ICU care, often persists for a prolonged period after onset of critical illness, and is a major contributor to the prolonged physical disability and slow rehabilitation process (14)**.

Recent data shows that 2 of 3 ICU survivors (65%) suffer significant functional limitations and impaired quality of life (6). Another recent study showed ICU patients (mean age: 55) are most likely to be discharged to post-acute care facilities and incur substantial costs of ~$3.5 million per functioning survivor (15). Studies of diverse populations consistently show ICU-survivors experience a high burden of muscle weakness, functional impairment and activity limitation (6, 16). In fact recent data reveal persistent functional limitation results in only 50% of patients returning to employment at 1 year after receiving ICU care (17, 18). Patients also have difficulty performing activities of daily living, and only reach 60%-65% of functional exercise capacity 12 months after onset of critical illness (8 **,(19, 20). Finally, survivors report prolonged weakness and loss of function following ICU care as the most concerning disabilities they experience (8)**. Thus, the question arises, are we creating survivors…or victims?. In response, ‘ICU Survivorship’ and addressing impaired quality of life and function in ICU survivors has been named “the defining challenge of critical care” for this century (21). The NIH along with all major ICU societies have recommended giving priority to research addressing quality of life issues after ICU treatment (22). Thus, a significant unmet need is thoroughly evident, and should engender development of new therapies to address the devastating impairments facing ICU survivors and improve their functional outcomes in this rapidly growing population.

Physical Rehabilitation/Exercise Interventions Alone Fail to Consistently Address Muscle Loss and Recovery of Quality of Life in ICU Survivors

The landmark Schweikert trial (23) found very early mobilization in mechanically ventilated medical ICU patients improved measures of physical function at hospital discharge. However, this trial did not examine long-term quality of life outcomes. Further, this study is yet to be meaningfully repeated in a broader ICU population (i.e. including surgical ICU patients). Unfortunately, the most recent (2018) meta-analysis of early rehabilitation in the ICU was unable to conclude whether early exercise in ICU improves patient muscle strength or quality of life after ICU care (24) **. Further, mixed results were seen for the effect of early exercise on physical function (24) **. In actual practice initiation of ICU rehabilitation is often markedly delayed or sometimes not delivered for many days after ICU admission. The mean time to commence rehabilitation in the ICU in the only 3 RCTs that have examined this question is 9 days after ICU admission (19, 23, 25). A large multi-site point prevalence study showed that less than 20% of ICU patients were mobilized out-of-bed at all (26). Unfortunately, the current usual standard of care of delayed ICU rehabilitation has shown limited benefit on any ICU-AW and quality of life outcomes (8) **. As stated in a recent review of interventions for Post-ICU Syndrome (PICS) article “Randomized controlled trials of physical rehabilitation interventions initiated several days after ICU admission have generally yielded no consistent evidence of benefit (8) **”. Further, very few studies examined the effect of rehabilitation after ICU care. A recent summary of this limited evidence concluded insufficient evidence was present to determine any effect on functional exercise capacity or quality of life for an exercise-based intervention initiated after ICU discharge (27). Unfortunately, no effect on quality of life was reported by any study examined. On balance, for optimal benefit it is clear rehabilitation should begin early in ICU stay and continue after ICU discharge. These data indicate that ICU exercise and rehabilitation, even controlled interventions in RCTs, fail to consistently improve physical function or quality of life. Thus, despite promising signals on some early outcomes after discharge from the ICU, it does not appear that ICU rehabilitation alone is sufficient to meaningfully address ICU-AW and improve function and quality of life in patients receiving ICU care.

Why Do ICU Rehabilitation Efforts Fail To Address Muscle and Physical Function Recovery in ICU Survivors?:

A primary explanation for the inability of current rehabilitation and exercise interventions to meaningfully address functional recovery and survivorship in ICU patients is the significant ongoing catabolism and anabolic resistance observed in critical illness, that extends well into the time after ICU care. High levels of muscle protein degradation (28) and sustained muscle atrophy leading to impaired muscle recovery (29) are strongly related to ongoing catabolism and inability to utilize available substrate for muscle anabolism and recovery. This is known to occur, despite adequate nutrition delivery and physical rehabilitation (29). Critically ill and injured patients can lose as much as a kilogram of lean body mass (LBM) per day (30). Patients often regain weight after ICU care, but much of this is fat mass accumulation rather than functional LBM gain (4). Adequate nutrition delivery is essential for ICU functional and LBM recovery and mitigates the extent of weight loss in ICU patients, but this is mostly via acquisition of additional fat mass (31). Interestingly, even with aggressive enteral feeding, where 2-3g/kg/day of protein is provided, skeletal muscle wasting continues to persist in ICU patients with burns. This persistent hypermetabolism and catabolism, which is currently not meaningfully addressed by even aggressive nutrition and/or exercise/rehabilitation interventions appear to be markedly hindering recovery of muscle mass and function, and ultimately meaningful “survivorship” in ICU survivors (30).

Role of Testosterone Deficiency in ICU Catabolism and Poor Functional Recovery

Critical illness is characterized by marked reductions in gonadal steroid production, significantly contributing to the catabolic state ubiquitously observed in the ICU (32). Initially, this likely reflects the global hormonal dysregulation seen in acute illness, and is commonly observed with other well-known hormones (insulin, cortisol). However, persistent hypotestosteronemia (Low-T) in acute illness contributes to impaired recovery and rehabilitation (32), as low-T conditions are correlated with disease severity and survival (32). Low-T discovered during hospitalization is associated with increased in-hospital (33) and long-term mortality (34), and predicts both all-cause mortality (35) and cardiovascular mortality (36) *. Specific to ICU patients who receive mechanical ventilation, low-T levels occur by day 3 in 94.4% (total T) and 100% (free T) of patients. In this study, total and free T levels correlated inversely with ventilator days and ICU length of stay (32). Low-T levels are also known to persist throughout ICU stay and into the period after ICU discharge. A study in patients after ICU care showed 96% of patients were testosterone deficient after ICU discharge (37). Thus, any intervention targeted to attenuate catabolism and muscle loss, must continue into the post-ICU period.

Benefits of testosterone and its analogues combined with rehabilitative exercise on clinical outcome and physical function have been demonstrated in a range of illnesses, although no studies of a combined multi-modal intervention examined physical function and muscle outcomes in non-burned critically ill patients at greatest risk of ICU-AW. A recent meta-analysis showed that testosterone improves exercise tolerance in heart failure patients (38). A randomized trial of an anabolic-targeted testosterone analogue nandrolone versus testosterone or placebo for HIV muscle-wasting showed improved weight gain and quality of life (39). COPD patients given the testosterone analogue nandrolone also showed improved muscle function and exercise capacity (40). Oxandrolone (OX), an easier to utilize oral anabolic-targeted testosterone analogue, is FDA-approved for use in ICU and surgical patients. Although little research has been conducted to support this indication in non-burn ICU patients, two small trials examined OX alone on basic clinical outcomes in surgical and trauma populations. A small trial in trauma patients gave OX during acute ICU phase and did not find differences in mortality or length of ICU stay (41). Another small study of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation (>7 d) showed a signal of prolonged ventilation days in OX group (42). Limitations include the question of whether low tidal ARDSnet volume strategies were employed, which is the current worldwide standard of care. Further, subjects in both groups only received 2~50% of calorie/protein delivery during the study, limiting potential of anabolic agent to benefit patients. Finally, OX was initiated later in ICU stay and was only given during ICU stay, and not in the critical period upon discharge from ICU when adequate nutrition delivery and recovery of muscle mass is more likely to occur. No described rehabilitation intervention, nor collection of muscle/physical function, quality of life, or direct muscle mass endpoints were conducted in either of these studies.

OX has been used successfully in a range of other settings to improve clinical and functional outcomes(43). In severe burns, many trials show benefits of OX administration (30) and it is a common standard of care in burn centers worldwide (personal communication: S Wolf). A recent burn injury trial, shows OX leads to gains in LBM, bone mineral content and muscle strength in critically ill burned children (44). Interestingly, lean mass was not found to be restored by the nutrition-treatment and standard usual care rehabilitation/physical therapy alone group in this study, showing nutrition and usual care rehabilitation is not sufficient to recover LBM without an anabolic stimulus (44). Importantly, the improvements from OX were maintained 6 months after discontinuation of OX. Other studies showed OX reduces mortality in severely burned patients (45), reduced muscle protein catabolism via improved protein synthesis efficiency (46), and reduced wound healing times and weight loss (47). Significant reductions in length of hospital stay were observed in a prospective randomized, multicenter study of OX in burn injury (48). A key trial also showed OX benefits were age-independent, as older adults (mean age-60) experienced similar benefits of reduced hospital LOS and improved muscle mass as younger patients (49). A meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 806 participants showed OX has significant benefits in severe burns treated in the ICU including reduced weight loss, increased lean body mass loss, decreased nitrogen loss, improved donor-site healing time, and reduced LOS without any increase in infection, metabolic rate, hyperglycemia, or liver dysfunction (50). Overall, this systematic review suggests OX is an effective and safe treatment in critically ill burn patients.

One factor potentially limiting wider-use of testosterone and its analogues in the ICU has been concern for association of testosterone and increased cardiacvascular and thromboembolic events (51). Concerns for these potential risks were dispelled by 2 large studies, including a ~43,000 subject trial showing teststerone-deficient persons, including most ICU patients receiving testosterone had a 33% reduction in all-cause cardiovascular events and 28% reduced stroke risk compared to those not treated (52). A second trial of 4,736 testosterone-deficient subjects receiving testosterone had 26% reduced 3-year Major Adverse CV Event (MACE) rate, and 35% reduced death rate compared to untreated subjects (53). In patients with known cardiovascular disease, untreated low testosterone levels were associated with higher 3-year MACE and death rates. Thus, testosterone supplementation, even in pre-existing cardiovascular/stroke-related disease, does not appear to lead to risk of adverse events. In fact, testosterone supplementation appears to reduce cardivascular/stroke risk in low-T patients. Thus, we suggest that treatment of common and pervasive testosterone deficiency in ICU patients may be a solution to facilitate the presumed benefit of structured rehabilitative exercise with adequate nutrition delivery, and improve function, quality of life, and recovery following ICU care. Studies to address this potential should be undertaken.

Suggestions for Testosterone and Oxandrolone Dosing:

See Table 1 for summary of commonly used Testosterone and Testosterone analogues. Testosterone and testosterone analoges have two primary properties: androgenic and anabolic. The different mechanisms include modulation of androgen receptor expression and interference of glucocorticoid receptor expression, which results in an anti-catabolic and anabolic effects. Targeted anabolic testosterone analouhes have modified the testosterone structure to maximize anabolic properties, while attempting to eliminate/minimize unwanted androgenic effects. Targeted anabolic testosterone agents such as oxandrolone or nandrolone exhibit significantly higher selectivity for muscle recovery and anabolic properties, with minimal androgenic effects (anabolic:androgenic activity ratio of 12:1 and 13:1, resp.)(54). Consequently, potential for adverse outcomes including aromatization and virilizing effects in women is significantly minimized.

Table 1:

Commonly Used Forms of Testosterone Supplements in ICU/Burn Setting

| - Oxandrolone: Commonly Utilized Dosing: 5-10 mg orally (PO) twice daily (typical adult dose: 10 mg) (doses used in ref 55-57) |

| ◦ Primarily anabolic with minimal androgenic effects |

| ◦ Minimal risk of liver enzyme elevation |

| ◦ Anabolic: androgenic activity ratio 13:1 (54) |

| - Nandrolone: Commonly Utilized Dosing: 100-200 mg (male) and 50-100 mg (female) intramuscularly weekly (doses discussed in ref 58) |

| ◦ Primarily anabolic with minimal androgenic effects |

| ◦ Anabolic: androgenic activity ratio 12:1 (54) |

| - Testosterone Cypionate: Commonly Utilized Dosing: 200-400 mg intramuscularly every 2 weeks (doses derived from package insert- see weblink*) |

| ◦ Relatively balanced ratio of anabolic to androgenic activity: 0.7–1.3:1 (54) |

| ◦ Commonly utilized outpatient testosterone replacement intervention |

| - Testosterone Patches: Example dose: 2-4 mg patch for patch specific number of days per application. Please note that different patch strengths and types exist? Check with local hospital pharmacy for specific patch type available and prescribing recommendations) |

| ◦ May be poorly absorbed in ICU patients due to edema and poor skin perfusion |

| ◦ May not adequately correct severe testosterone deficiencies present in ICU patients |

Care Notes:

-Check regular (weekly) testosterone levels when giving primary testosterone preparations to ensure adequate correction (Testosterone level- > 240 ng/dL ) and to avoid elevated testosterone levels (> 950 ng/dL) (per Mayo Clinic Reference Lab normal values).

- Check regular (weekly) Liver function tests for AST/ALT to follow liver enzyme elevations that are rarely related to testosterone therapy

Testosterone Cypionate package insert: https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=f60c5520-b336-44a2-95d5-f274939fa595&type=display

Typical adult dosing used in studies of burned patients from our preliminary results and previous literature in burn injury and other illnesses show 10 mg 2 x day has been effective in improving muscle strength, muscle function and clinical outcomes (55-57). In most studies this is given starting a few days after hospital admission (typically within 96 hours of ICU admission) until hospital discharge. Nandrolone, an anabolic specific testosterone agent, has also been published in case reports of ICU patients to address ICU-acquired weakness(58)*. Other testosterone delivery methods may also be effective, such as traditional intramuscular testosterone cypionate (which is a common outpatient testosterone replacement formaulations) given at a dose of 200-400 mg every 2 weeks. Testosterone patches can also be utilized (typical dose supplied 4 mg patch) although this often is not as effective absorbed in critically ill patients with edema and altered skin perfusion and may not adequately correct thee severe deficiencies seen in ICU patients. Following testosterone levels throughout care is essential to ensure adequate testosterone replacement is occurring with elevated levels being observed. Further, weekly liver function tests should be monitored, although elevations of LFTs from shorter-term ICU oxandrolone and testosterone use are relatively rare.(55-57).

Structured, Multi-Domain Rehabilitation (MDR):

An intervention that addresses multiple domains necessary for independent physical function, that is individually tailored with targeted milestones for progression, and that extends through the hospital stay has yet to be fully explored in patients with critical illness. A potential model of interest is that used in the NIH-funded REHAB-Heart Failure (HF) trial (clinicaltrails.gov NCT02196038), which implemented MDR for HF patients with profound physical deficits paralleling those found in critically illness (59**-61).

The REHAB-HF MDR intervention is an application of proven rehabilitation therapies selected and integrated specifically to target deficits in physical function precipitated by acute illness (59)**. The goal of the intervention is to increase functional performance across the four physical function domains of strength, balance, mobility, and endurance using reproducible, targeted exercises with, importantly, specific milestones for progression. The relative time spent on each physical function domain during a rehabilitation session is tailored to the patient’s deficits. For example, a patient with poor balance and functional mobility spends a greater proportion of time performing balance and mobility exercises in the early stages of the intervention. Alternatively, a patient with adequate balance and mobility spends most of the session performing endurance and strengthening. Strengthening rehabilitation include functional strengthening exercises on the lower extremities (i.e., closed chain sit-to-stand, step-ups, calf/toe raises). Balance rehabilitation incorporates static exercises, including progressively narrowing base of support with eyes open or closed, and dynamic exercises, including reaching forward and backward starting within base of support and progressing to outside base of support. Mobility rehabilitation includes dynamic start and stop while walking, changing direction while walking, and episodes of decelerated and accelerated gait. Endurance rehabilitation includes walking as the preferred mode. The MDR intervention would begin once the ICU patient can voluntarily participate (i.e., post-sedation, stable vitals) and continue through hospital discharge.

Role of Nutrition in ICU Recovery utilizing anabolic agents and structured exercise:

Adequate nutrition delivery must be assured to optimize potential benefit of OX and exercise intervention. A structured nutrition delivery strategy is optimal for achieving this successfully as described in recent review on ICU and post-ICU nutrition (62)**. Another excellent algorithm is described in the recently published EFFORT trial. This multi-center randomized trial studied acutely ill hospitalized patients at high nutrition risk(63)** and found a structured nutrition algorithm led to significant reductions in mortality and complications at 30 days. Importantly, the nutrition algorithm should be adapted for the ICU and after ICU discharge to lead to significant improvement in recovery and functional independence (p< 0.006) and EQ-5D QoL at 30 d (p=0.018). Thus, we believe using a structured feeding algorithm and the long-studied nutrition strategies described should optimize necessary nutrition delivery in the ICU

Conclusion

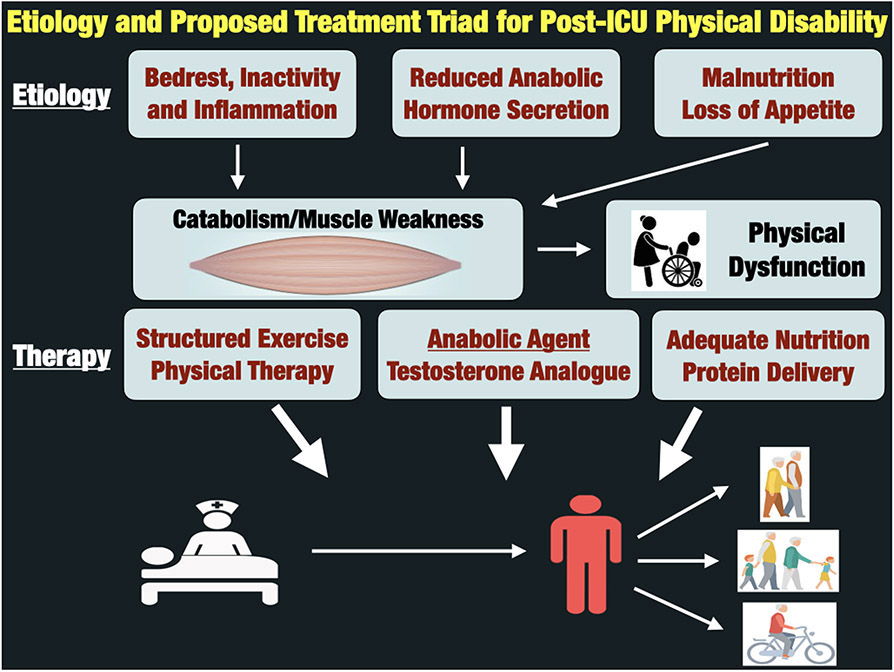

In conclusion, critical illness leads to a catabolic state, including severe testosterone deficiency, that persists throughout hospital stay. This results in persistent muscle weakness, physical dysfunction and impaired functional QoL. We believe the combination of an anabolic agent with early exercise and adequate nutrition is the essential triad required to optimize muscle mass/strength and physical function in ICU survivors (See Figure 1). We belive all three key pathways (anabolism, exercise and nutrition) must be addressed in an ICU recovery intervention if we hope to ultimately improve “ICU Survivorship”, address impaired post-ICU quality of life in ICU survivors and triump over “the defining challenge of critical care” for this century(22).

Figure 1:

Etiology and Proposed Treatment Triad for Post-ICU Physical Disability

Key Points:

ICU survivors experience a high burden of muscle weakness, functional impairment and activity limitation, currently existing standards of ICU rehabilitative care when studied in trials are failing to successfully address these disabilities.

One explanation for lack of success of ICU rehabilitation trials is most all ICU patients exhibit severe testosterone deficiencies early in ICU stay contributing to persistent catabolism and potentially underlying lack of response to current physical therapy interventions.

Oxandrolone is an FDA-approved testosterone analogue for treating muscle weakness in ICU patients and a growing number of trials with this agent combined with strutured exercise show clinical benefit, including improved physical function and safety in burns and other catabolic states.

Currently, no trials of oxandrolone or other anabolic testosterone analougues and structured exercise in non-burn ICU populations have been conducted- thus this research is urgently needed.

The combination of an anabolic agent with adequate nutrition and structured exercise is likely essential to optimize muscle mass/strength and physical function in ICU survivors.

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Linda Denehy B App Sc (Physiotherapy), PhD for her tremendous and wise insight on ICU rehabilitation and potential research and trial design concepts for combination of anabolic agents and exercise in the ICU setting.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

PEW- Has received grant funding related to this work from NIH, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Abbott, Baxter, Fresenius, Nutricia, and Takeda. PEW serves as a consultant to Abbott, Fresenius, Baxter, Nutricia, and Takeda for research related to nutrition in surgery and ICU care; received unrestricted gift donation for surgical and critical care nutrition research from Musclesound and Cosmed; received honoraria or travel expenses for CME lectures on improving nutrition care in surgery and critical care from Abbott, Baxter, Nutricia, and Fresenius. OS – receives grant funding from the NIH JW- receives grant funding support from the International Anesthesiology Research Society (IARS). SEW – receives grant funding from the NIH and NIDILRR JM- Receives research grant funding from Nutricia, MuscleSound, and Cosmed. AP- Has received grant funding related to this work from NIH, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, PCORI and American Physical Therapy Association. RK- declares funding from DOD and NIH.

References:

- 1.Milbrandt EB, Kersten A, Rahim MT, Dremsizov TT, Clermont G, Cooper LM, et al. Growth of intensive care unit resource use and its estimated cost in Medicare. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(9):2504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talmor D, Shapiro N, Greenberg D, Stone PW, Neumann PJ. When is critical care medicine cost-effective? A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness literature. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11):2738–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. Jama. 2014;311(13):1308–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):683–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(14):1293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kress JP, Hall JB. ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1626–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinglas VD, Aronson Friedman L, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz CB, Ciesla ND, et al. Muscle Weakness and 5-Year Survival in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **8. Brown SM, Bose S, Banner-Goodspeed V, Beesley SJ, Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, et al. Approaches to Addressing Post-Intensive Care Syndrome among Intensive Care Unit Survivors. A Narrative Review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(8):947–56. Key excellent recent review article on interventions to address PICS in ICU survivors. Data presented demonstrates recent studies of late ICU rehabilitation efforts are showing limited benefit of on ICU-acquired weakness and QoL outcomes. A “must-read” article in ICU recovery field.

- 9.Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. Jama. 2013;310(15):1591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *10. Wernerman J, Christopher KB, Annane D, Casaer MP, Coopersmith CM, Deane AM, et al. Metabolic support in the critically ill: a consensus of 19. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):318. Recent consensus conference review article summarizing current knowledge and questions to be answered in ICU metabolism.

- 11.Truong AD, Fan E, Brower RG, Needham DM. Bench-to-bedside review: mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit--from pathophysiology to clinical trials. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Preiser JC, van Zanten AR, Berger MM, Biolo G, Casaer MP, Doig GS, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care. 2015;19:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(2):371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **14. van Gassel RJJ, Baggerman MR, van de Poll MCG. Metabolic aspects of muscle wasting during critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23(2):96–101. Excellent review of muscle wasting in critical illnes

- 15.Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, Hopkins RO, Rice TW, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):725–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins RO, Suchyta MR, Kamdar BB, Darowski E, Jackson JC, Needham DM. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living after Critical Illness: A Systematic Review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(8):1332–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1293–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Wozniak AW, Rice TW, et al. One year outcomes in patients with acute lung injury randomised to initial trophic or full enteral feeding: prospective follow-up of EDEN randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346:f1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denehy L, Skinner EH, Edbrooke L, Haines K, Warrillow S, Hawthorne G, et al. Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical illness: a randomized controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up. Crit Care. 2013;17(4):R156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, Jackson JC, Hough CL, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding. EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(5):567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwashyna TJ. Survivorship will be the defining challenge of critical care in the 21st century. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(3):204–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham CO 3rd, et al. Core Outcome Measures for Clinical Research in Acute Respiratory Failure Survivors. An International Modified Delphi Consensus Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(9):1122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **24. Doiron KA, Hoffmann TC, Beller EM. Early intervention (mobilization or active exercise) for critically ill adults in the intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD010754. Comprehensive recent met-analysis of early mobilization and rehabilitation trials in critical illness

- 25.Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, Ferdinande P, Langer D, Troosters T, et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(9):2499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berney SC, Harrold M, Webb SA, Seppelt I, Patman S, Thomas PJ, et al. Intensive care unit mobility practices in Australia and New Zealand: a point prevalence study. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15(4):260–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connolly B, Salisbury L, O'Neill B, Geneen L, Douiri A, Grocott MP, et al. Exercise rehabilitation following intensive care unit discharge for recovery from critical illness: executive summary of a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7(5):520–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaude M, Mori M, Tjader I, Gustafsson T, Wernerman J, Rooyackers O. Protein metabolism and gene expression in skeletal muscle of critically ill patients with sepsis. Clin Sci (Lond). 2012;122(3):133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dos Santos C, Hussain SN, Mathur S, Picard M, Herridge M, Correa J, et al. Mechanisms of Chronic Muscle Wasting and Dysfunction after an Intensive Care Unit Stay. A Pilot Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(7):821–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanojcic M, Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG. Anabolic and anticatabolic agents in critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22(4):325–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart DW, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, Chinkes DL, Lal SO, Obeng MK, et al. Energy expenditure and caloric balance after burn: increased feeding leads to fat rather than lean mass accretion. Ann Surg. 2002;235(1):152–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almoosa KF, Gupta A, Pedroza C, Watts NB. Low Testosterone Levels are Frequent in Patients with Acute Respiratory Failure and are Associated with Poor Outcomes. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(10):1057–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iglesias P, Prado F, Macias MC, Guerrero MT, Munoz A, Ridruejo E, et al. Hypogonadism in aged hospitalized male patients: prevalence and clinical outcome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37(2):135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muraleedharan V, Jones TH. Testosterone and mortality. Clinical endocrinology. 2014;81(4):477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shores MM, Matsumoto AM, Sloan KL, Kivlahan DR. Low serum testosterone and mortality in male veterans. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36. Rallidis LS, Kotakos C, Tsalavoutas S, Katsimardos A, Drosatos A, Rallidi M, et al. Low Serum Free Testosterone Association With Cardiovascular Mortality in Men With Stable CAD. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(21):2674–5. New article showing low testosterone is associated with and predicts increased cardiovascular mortality in men with coronary artery disease.

- 37.Nierman DM, Mechanick JI. Hypotestosteronemia in chronically critically ill men. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(11):2418–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Toma M, McAlister FA, Coglianese EE, Vidi V, Vasaiwala S, Bakal JA, et al. Testosterone supplementation in heart failure: a meta-analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(3):315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sardar P, Jha A, Roy D, Majumdar U, Guha P, Roy S, et al. Therapeutic effects of nandrolone and testosterone in adult male HIV patients with AIDS wasting syndrome (AWS): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. HIV Clin Trials. 2010;11(4):220–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schols AM, Soeters PB, Mostert R, Pluymers RJ, Wouters EF. Physiologic effects of nutritional support and anabolic steroids in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A placebo-controlled randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4 Pt 1):1268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gervasio JM, Dickerson RN, Swearingen J, Yates ME, Yuen C, Fabian TC, et al. Oxandrolone in trauma patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(11):1328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bulger EM, Jurkovich GJ, Farver CL, Klotz P, Maier RV. Oxandrolone does not improve outcome of ventilator dependent surgical patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240(3):472–8; discussion 8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gullett NP, Hebbar G, Ziegler TR. Update on clinical trials of growth factors and anabolic steroids in cachexia and wasting. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(4):1143S–7S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demling RH, DeSanti L. Oxandrolone induced lean mass gain during recovery from severe burns is maintained after discontinuation of the anabolic steroid. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2003;29(8):793–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gauglitz GG, Williams FN, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. Burns: where are we standing with propranolol, oxandrolone, recombinant human growth hormone, and the new incretin analogs? Curr Opin Clin Nutr. 2011;14(2):176–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hart DW, Wolf SE, Ramzy PI, Chinkes DL, Beauford RB, Ferrando AA, et al. Anabolic effects of oxandrolone after severe burn. Ann Surg. 2001;233(4):556–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demling RH, Orgill DP. The anticatabolic and wound healing effects of the testosterone analog oxandrolone after severe burn injury. J Crit Care. 2000;15(1):12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf SE, Edelman LS, Kemalyan N, Donison L, Cross J, Underwood M, et al. Effects of oxandrolone on outcome measures in the severely burned: a multicenter prospective randomized double-blind trial. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27(2):131–9; discussion 40-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demling RH, DeSanti L. The rate of restoration of body weight after burn injury, using the anabolic agent oxandrolone, is not age dependent. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2001;27(1):46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Guo Y, Yang Z, Roy M, Guo Q. The efficacy and safety of oxandrolone treatment for patients with severe burns: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns : journal of the International Society for Burn Injuries. 2016;42(4):717–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, Adams JL, Frasco MA, Cook MB, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheetham TC, An J, Jacobsen SJ, Niu F, Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, et al. Association of Testosterone Replacement With Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Men With Androgen Deficiency. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(4):491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson JL, May HT, Lappe DL, Bair T, Le V, Carlquist JF, et al. Impact of Testosterone Replacement Therapy on Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, and Death in Men With Low Testosterone Concentrations in an Integrated Health Care System. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(5):794–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kicman AT. Pharmacology of anabolic steroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(3):502–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Przkora R, Herndon DN, Suman OE. The effects of oxandrolone and exercise on muscle mass and function in children with severe burns. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith BA, Raper JL, Weaver MT, Bittner VA, Gower B, Hunter GR, et al. Double blind placebo controlled study of exercise and oxandrolone on lean mass, fat distribution, blood lipids, bone density and training markers in HIV infected men and women on HAART The XV International AIDS Conference2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeschke MG, Finnerty CC, Suman OE, Kulp G, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. The effect of oxandrolone on the endocrinologic, inflammatory, and hypermetabolic responses during the acute phase postburn. Ann Surg. 2007;246(3):351–60; discussion 60-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *58. Anstey M, Desai S, Torre L, Wibrow B, Seet J, Osnain E. Anabolic Steroid Use for Weight and Strength Gain in Critically Ill Patients: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Crit Care. 2018;2018:4545623. Case series describing potential role and benefit of nandrolone for weight gain and ICU-related muscle weakness. Good review of anabolic testosterone analogue pharmacology.

- **59. Pastva AM, Duncan PW, Reeves GR, Nelson MB, Whellan DJ, O'Connor CM, et al. Strategies for supporting intervention fidelity in the rehabilitation therapy in older acute heart failure patients (REHAB-HF) trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;64:118–27. This article presents a working model for maintaining intervention fidelity in physical intervention trials and illustrates how the intervention fidelity strategies align with the Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium recommendations.

- 60.Reeves GR, Whellan DJ, O'Connor CM, Duncan P, Eggebeen JD, Morgan TM, et al. A Novel Rehabilitation Intervention for Older Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: The REHAB-HF Pilot Study. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5(5):359–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reeves GR, Whellan DJ, Duncan P, O'Connor CM, Pastva AM, Eggebeen JD, et al. Rehabilitation Therapy in Older Acute Heart Failure Patients (REHAB-HF) trial: Design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2017;185:130–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **62. van Zanten ARH, De Waele E, Wischmeyer PE. Nutrition therapy and critical illness: practical guidance for the ICU, post-ICU, and long-term convalescence phases. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):368. Excellent and comprehensive review of ICU nutrition delivery across all phases of ICU and post-ICU care

- **63. Schuetz P, Fehr R, Baechli V, Geiser M, Deiss M, Gomes F, et al. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10188):2312–21. Critical new large multi-center randomized controlled trial of a structured nutrition intervention in malnourished hospitalized patients led to significant reductions in mortality and complications at 30 days. The early malnutrition intervention also led to significant improvement in recovery and functional independence (p< 0.006) and EQ-5D QoL at 30 d (p=0.018).