A few studies have compared the prevalence of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) seropositivity or incidence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among healthcare workers (HCWs) based on their degree of exposure to COVID-19 patients, but these data show conflicting results.1–5 Here, we longitudinally characterized the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections among nurses working in COVID-19 units versus non–COVID-19 units throughout the first year of the pandemic.

Methods

This longitudinal observational study was conducted at Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital (FMLH), a 607-bed academic hospital in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Using the Enterprise Internal Occupational Health (IOH) Department’s employee logs, we identified all consecutive, unique HCWs who met definition of nurse and who had a SARS-CoV-2 positive test (regardless of symptoms) between March 20, 2020, and March 28, 2021. Early in the pandemic, tests were ordered by IOH based on either symptoms or exposures, but as time progressed, only orders based on documented exposures were ordered by IOH. However, HCWs or their supervisors were required to notify IOH of positive results prior to home isolation. Data obtained from IOH included the HCW name, specialty, and hospital inpatient unit, date, and COVID-19 test results. Symptoms were entered as text in a separate, confidential IOH database, and thus were not available for this investigation. To ensure that providers were as fixed as possible to a unit rather than providing care to several units (eg, physicians, therapists), this study included only nurses assigned to inpatient settings. Nurses were defined as either registered nurses, charge nurses, nurse managers, external nurses, or clinical nurse specialists. Anecdotally, shift movements of nurses between COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 units were not common. Additionally, no special screening tests were performed among staff assigned to COVID-19 units.

For this study, SARS-CoV-2 rates were defined as the percentage of positive nurses per 100 total active nurses per unit per month. The number of nurses per unit per month was obtained from the human resources department (ie, aggregate deidentified data).

To compare SARS-CoV-2 incidence rates between COVID-19 units and non–COVID-19 units by month, we used the Fisher exact test for each month and adjusted for multiple testing.6

Results

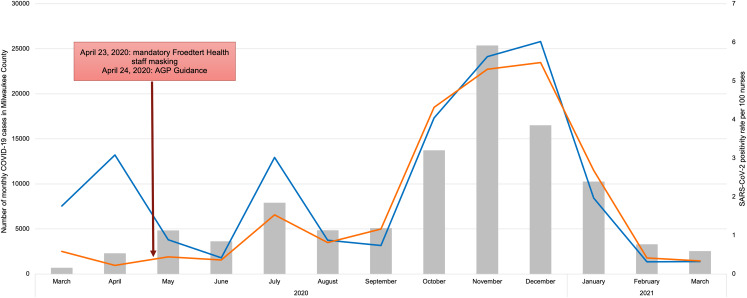

In total, 1,452 inpatient HCWs were SARS-CoV-2 positive and 375 (25.8%) met the definition of nurses. Also, 79 nurses reported a positive SARS-CoV-2 test in COVID-19 units compared to 296 in non–COVID-19 units (Fig. 1). The overall incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infections was 29.7 per 100 nurses in COVID-19 units versus 22.9 per 100 nurses in non–COVID-19 units (P = .039).

Fig. 1.

Incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 among nurses in COVID-19 units and non–COVID-19 units. Blue line indicates COVID-19 units. Orange line indicates non–COVID-19 units. Grey bars indicate total number of monthly COVID-19 cases in Milwaukee County. Note. AGP, aerosol-generating procedures.

Figure 1 shows the incidence rate across COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 units by month during the study period. We detected 2 months in which the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 was higher among nurses assigned to COVID-19 units than those of non–COVID-19 units: April 2020 (3.08 vs 0.22; P = .004) and July 2020 (3.01 vs 1.53; P = 1) (Supplementary Table 1 online). When the largest wave of cases was experienced in the community during the fall season, no statistically significant differences were observed between the 2 types of units. Controlling for false discovery rate assumed at 5%, the difference between the incidence rate in COVID-19 units and non–COVID-19 units was statistically significant only in April 2020.

Discussion

In this observational study, the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 positivity among nurses assigned to COVID-19 units was remarkably similar to non–COVID-19 units, except during April 2020. Interestingly, universal goggles and masking were made mandatory on April 23, 2020; thus, this factor was almost certainly associated with decreases in infection rates in COVID-19 units. Notably, during the fall months with highest incidence of COVID-19 in the community, the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 among nurses was the same regardless of their unit, suggesting community exposures rather than hospital-based exposures.

Two studies reported higher infection rates among HCWs working in COVID-19 units versus non–COVID-19 units.2,3 However, these studies did not evaluate changes in the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections over time. Another publication found a higher rate of COVID-19 infections (95%) among HCWs in non–COVID-19 facilities compared to COVID-19 facilities (5%) which seemed to be inversely associated to compliance with personal protective equipment (82% and 68% in COVID-19–designated and non–COVID-19–designated facilities, respectively).7 Other studies failed to find differences in COVID-19 incidence rates based on COVID-19 unit designation.5,6

The limitations of our study included the lack of data regarding demographics, comorbidities, and presence and type of symptoms among nursing staff. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 positivity was based on self-reported data (by HCW or supervisor) to IOH; however, this notification was required for any HCW to be placed on home isolation following a positive test. The number of nurse days would have been the ideal denominator but unfortunately, these data were not available to us. Despite this limitation, the incidence rates between the groups were identical after the institution of universal masking. This finding suggests that issues related to the suboptimal denominators may have been balanced in the 2 groups. In addition, we did not have compliance data related to infection control measures. However, personal protective equipment was available in all units throughout the pandemic. Finally, our results represent a single-center experience, so caution is warranted when generalizing these data to other settings.

In summary, we observed that the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 among nurses was the same in COVID-19 units as in non–COVID-19 units after implementing universal masking and eye protection. This finding is encouraging because it indicates that hospital systems are able to protect their personnel while providing care to the COVID-19 population through the implementation of infection control recommendations.

Acknowledgments

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.352.

click here to view supplementary material

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Gómez-Ochoa S, Franco O, Rojas L, et al. COVID-19 in healthcare workers: a living systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2021;190:161–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Çelebi G, Pişkin N, Çelik Bekleviç A, et al. Specific risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 transmission among health care workers in a university hospital. Am J Infect Control 2020;48:1225–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccoli L, Ferrari P, Piumatti G, et al. Risk assessment and seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers of COVID-19 and non–COVID-19 hospitals in southern Switzerland. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suárez-García I, Martínez de Aramayona López MJ, Sáez Vicente A, Lobo Abascal P.SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers in a hospital in Madrid, Spain. J Hosp Infect 2020;106:357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boffetta P, Violante F, Durando P, et al. Determinants of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Italian healthcare workers: a multicenter study. Sci Rep 2021;11:5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli, D.The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann Stat 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alajmi J, Jeremijenko AM, Abraham JC, et al. COVID-19 infection among healthcare workers in a national healthcare system: the Qatar experience. Int J Infect Dis 2020;100:386–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ice.2021.352.

click here to view supplementary material