Abstract

Background

A “boot camp” or senior preparatory course can help to bridge the gap between knowledge and skills attained in required clerkships and residency expectations. An under-researched area is in interventions across specialties and with student confidence as the outcome.

Objective

A multi-specialty school-wide boot camp for 4th year medical students was evaluated with a curriculum that focused on specialty milestones and entrustable professional activities and the importance of student confidence as an outcome.

Methods

A school-wide “boot camp” was developed to help 4th year students become ready for their matched specialty. Faculty resources were pooled to teach students from multiple specialties’ common milestone topics. Surveys were collected from 3 academic years (2014–2015 to 2016–2017): pre-boot camp (Pre), immediately post-boot camp (Post 1), and 3 months after starting residency (Post 2). Dependent t-tests were employed to determine pre-post differences.

Results

Over the 3-year study period, 185 students participated in boot camp, 162 (87.6%) completed the first 2 surveys, and 75 (40.5%) students provided data at all 3 points in time. With more robust findings between Pre and Post 1, students improved their confidence level in communicating with families and most specialty skills, and students felt more prepared to be an intern as a result of the boot camp.

Conclusions

The robust increase in student confidence suggested that a multi-specialty, school-wide approach to a capstone curriculum should be considered by medical schools, which will not only benefit students but faculty as well. Future research should examine student competence in achieving specialty skills.

Keywords: Boot camp, Milestones, Entrustable professional activities, Faculty resources

Introduction

Medical students are expected to possess a wide array of knowledge, skills, and attitudes at graduation and upon entering residency training programs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) created milestones to assess the competency of learners during residency [1]. At graduation, these newly minted interns are expected to be Level 1 milestone-ready at a minimum. In addition, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) developed entrustable professional activities (EPA) that all medical graduates should be entrustable with minimal supervision on day one of residency [2]. Clerkship requirements that students complete during their 3rd year of medical school do not necessarily match with the Level 1 milestones and entrustability of all EPAs that students are expected to have on their first day as interns.

Residency program directors and supervising faculty have expressed concern that some of the incoming interns are not well prepared for residency [3–5]. Graduating students have had low confidence in their ability to perform core EPAs, including procedural skills [3, 6]. Incoming intern competency also falls below expectations of medical student graduates, particularly in the areas of communication skills and prescribing [7–9].

A “boot camp” or senior preparatory course can help to bridge the gap between knowledge and skills attained in required clerkships with medical school graduation requirements and residency expectations [10]. Some schools refer to this senior preparatory course as a “capstone” course or “boot camp” course. A “boot camp” curriculum of intensive procedural and skills training can help medical students practice clinical skills and procedural techniques [11, 12]. Residency programs have also adopted boot camps to teach their residents procedural skills [13, 14]. While a few schools now have an integrated (including various specialties) school-wide boot camp, to our knowledge, there has not been a study to determine whether an integrated school-wide “boot camp” with a curriculum that focuses on specialty milestones and EPAs can enhance the preparation of medical students for their residency training. Our boot camp could be considered partly as a refresher course as students are exposed to EPAs during clerkships and 4th year rotations; however, we wanted to assess whether their confidence in performing these important skills would improve after completing this refresher training.

Student confidence is an often-neglected outcome when evaluating medical student curriculum and instruction. On a general level, confidence is a component of the important construct of self-efficacy [15]. In particular to health education, confidence has been shown to be important to residents’ ability to lead and gain trust in a team [16], and confidence has also been found to correlate substantially with medical student competence [17].

The primary objective of our project was to determine if an integrated school-wide milestone-driven boot camp increased student self-confidence in residency milestone-related skills and EPAs.

Methods

Program Description

We created a multi-specialty, school-wide “boot camp” at the John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM) of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa as part of the mandatory curriculum for all 4th year medical students. Clerkship directors from each of the disciplines (i.e., Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Psychiatry, Family Medicine, and Emergency Medicine) met as an integrated team to discuss what our students would need for their specialty. Each clerkship director focused on specialty milestones and relevant EPA skills and developed his or her specialty boot camp topics. We pooled faculty resources and grouped the students into larger sessions for milestones common across all disciplines and EPAs, such as communication and transitions of care. For more specific milestones, such as suturing, one workshop was conducted for students entering Surgery, Family Medicine, Obstetrics/Gynecology (OB/GYN), and Emergency Medicine specialties. Another example of integration included Family Medicine, Emergency Medicine, and Pediatric students who participated in an infant lumbar puncture workshop taught by Pediatric faculty. Psychiatry students also participated in primary care modules.

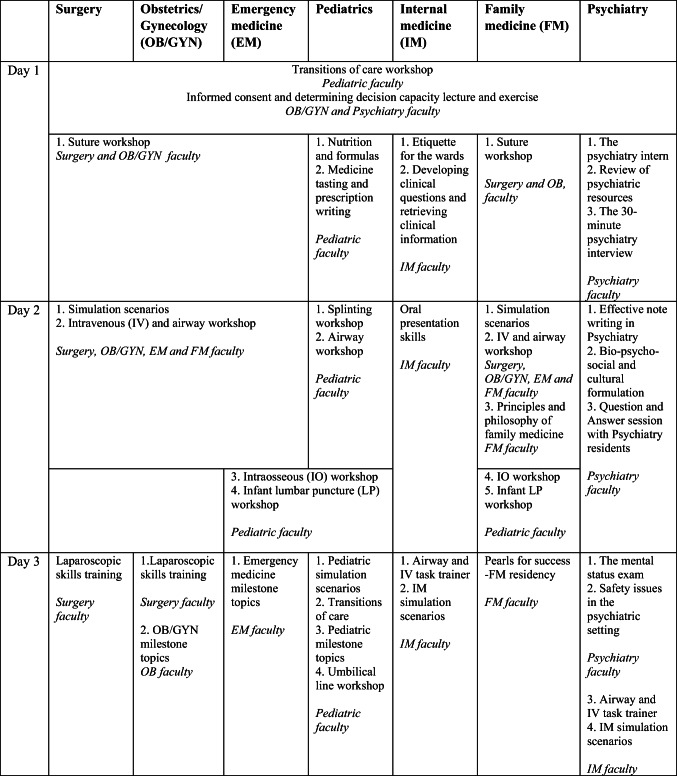

This boot camp was conducted over 2 days in 2015 and 3 days in 2016 and 2017, as part of a week-long senior seminar curriculum. Topics were added in 2016 and 2017 to enhance the specialty content of the boot camps, which were added to the 3rd day of curricula. The boot camp schedule is provided in Table 1. The table lists the school-wide and specialty topics selected by the clerkship director of specialties and how the workshops were scheduled. The specialty faculty who conducted the sessions are also listed in the table. Every student participated in the boot camp as it was included as part of a mandatory curriculum.

Table 1.

Boot camp schedule of topics

Each module was developed by faculty with special interest or expertise in the specialty topic. Clerkship directors collaborated to determine which students would benefit from participation in which specific modules.

Sample Description

Surveys were collected from 3 academic years (2014–2015 to 2016–2017). Across the 3-year period, there were 185 students who completed the boot camp and participated in the first survey and 162 (87.6%) medical students who completed the first 2 surveys, and 75 (40.5%) students provided data at all 3 points in time. A total of 187 students participated in the boot camp, with 2 declining to participate in the study surveys. The residencies these students were entering were as follows: 8 Emergency Medicine; 15 Family Medicine; 53 Internal Medicine; 6 Obstetrics & Gynecology; 21 Pediatrics; 13 Psychiatry; 41 Surgery; and 5 not indicated or other. Our study was anonymous. We did not collect gender data as this could have been used to identify students in specialties with smaller numbers of participants.

Measures

The survey contained questions of student confidence level pertaining to skills that were taught during the boot camp. The specific wording of the items was derived by the boot camp leaders and respective specialists. The survey included 48 items (with Cronbach alpha of the Pre boot camp item as an indicator of internal consistency and reliability): 3 general (0.50); 8 Emergency Medicine (0.89); 6 Family Medicine (0.68); 5 Internal Medicine (0.84); 5 Obstetrics and Gynecology (0.83); 8 Pediatrics (0.86); 7 Psychiatry (0.94); and 4 Surgery (0.73). Table 2 provides the exact wording for each item. All items were rated on a 1–5 scale (1 = no confidence; 3 = some confidence; 5 = complete confidence). For each set of specialty items, a composite score was derived by computing the mean of the respective items. All students were asked to complete the 3 general survey questions regarding the common sessions and then to complete their respective specialty survey questions.

Table 2.

Comparisons between Pre and Post 1, Pre and Post 2, and Post 1 and Post 2

| Item No. | Description | Pre vs. Post 1 | Pre vs. Post 2 | Post 1 vs. Post 2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post 1 | Pre | Post 2 | Post 1 | Post 2 | |||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | N | M | SD | M | SD | N | M | SD | M | SD | N | ||

| Generala | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | I am prepared to function as an intern | 2.81 | 0.91 | 3.49 | 0.77 | 162 **** | 2.86 | 0.80 | 3.70 | 0.74 | 79 **** | 3.55 | 0.74 | 3.68 | 0.74 | 75 |

| 2 | A 3 day long intern prep course is worthwhile | 3.87 | 0.95 | 4.37 | 0.84 | 160 **** | 3.94 | 0.96 | 4.25 | 0.80 | 77 ** | 4.49 | 0.78 | 4.24 | 0.79 | 75 * |

| 3 | I can communicate with patients effectively | 3.14 | 0.91 | 3.74 | 0.78 | 160 **** | 3.16 | 0.85 | 3.95 | 0.64 | 79 **** | 3.77 | 0.80 | 3.96 | 0.65 | 75 * |

| Emergency Medicine (EM) - Overall | 3.70 | 0.60 | 4.30 | 0.43 | 8 ** | 3.25 | 0.00 | 4.31 | 0.09 | 2 | 3.94 | 0.09 | 4.31 | 0.09 | 2 | |

| 1 | I am comfortable recognizing abnormal vital signs | 4.25 | 0.71 | 4.63 | 0.52 | 8 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.50 | 0.71 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 2 | I am comfortable managing a single patient amidst distractions | 3.88 | 0.83 | 4.50 | 0.76 | 8 * | 3.50 | 0.71 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 1.41 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 3 | I am comfortable performing basic airway maneuvers or adjuncts (jaw thrust/chin lift/oral airway/nasopharyngeal airway) and ventilating/oxygenating a patient using BVM | 3.63 | 0.52 | 4.50 | 0.53 | 8 ** | 3.50 | 0.71 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 4 | I am comfortable performing local anesthesia using appropriate doses of local anesthetic and appropriate technique to provide skin to sub- dermal anesthesia for procedures | 4.00 | 0.76 | 4.63 | 0.52 | 8 * | 4.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 5 | I am comfortable performing basic suturing | 4.25 | 0.71 | 4.63 | 0.52 | 8 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 2 |

| 6 | I am comfortable performing venipuncture | 3.50 | 0.76 | 4.25 | 0.71 | 8 * | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 4.00 | 1.41 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| 7 | I am comfortable placing a peripheral intravenous Line | 3.50 | 0.93 | 4.13 | 0.64 | 8 * | 3.00 | 0.00 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| 8 | I am comfortable performing an arterial puncture | 2.63 | 1.51 | 3.13 | 1.25 | 8 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 1.50 | 0.71 | 2.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| Family Medicine (FM) - Overall | 4.28 | 0.43 | 4.84 | 0.26 | 15 *** | 4.17 | 0.52 | 4.42 | 0.42 | 6 | 4.81 | 0.34 | 4.42 | 0.42 | 6 | |

| 1 | I recognize that effective relationships are important to quality of care | 4.67 | 0.49 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 15 * | 4.67 | 0.52 | 4.50 | 0.55 | 6 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 4.50 | 0.55 | 6 |

| 2 | I recognize that respectful communication is important to quality of care | 4.60 | 0.51 | 4.93 | 0.26 | 15 * | 4.67 | 0.52 | 4.50 | 0.55 | 6 | 4.83 | 0.41 | 4.50 | 0.55 | 6 |

| 3 | I am able to identify physical, cultural, psychological, and social barriers to communication | 4.23 | 0.68 | 4.67 | 0.62 | 15 ** | 4.17 | 0.75 | 4.17 | 0.41 | 6 | 4.67 | 0.52 | 4.17 | 0.41 | 6 |

| 4 | I am able to use the medical interview to establish rapport and facilitate patient-centered information exchange | 3.80 | 0.68 | 4.60 | 0.63 | 15 ** | 3.50 | 0.84 | 4.17 | 0.41 | 6 | 4.67 | 0.52 | 4.17 | 0.41 | 6 |

| 5 | I acknowledge that patients with undifferentiated signs, symptoms, or health concerns are appropriate for the family physician and am committed to addressing their concerns | 4.07 | 0.88 | 4.93 | 0.26 | 15 ** | 3.83 | 1.17 | 4.67 | 0.52 | 6 | 4.83 | 0.41 | 4.67 | 0.52 | 6 |

| 6 | I recognize that an in-depth knowledge of the patient and broad knowledge of the sciences are essential to the work of the family physicians | 4.33 | 0.82 | 4.93 | 0.26 | 15 * | 4.17 | 1.17 | 4.50 | 0.55 | 6 | 4.83 | 0.41 | 4.50 | 0.55 | 6 |

| Internal Medicine (IM) - Overall | 3.08 | 0.59 | 3.91 | 0.51 | 53 **** | 2.93 | 0.67 | 3.99 | 0.48 | 24 **** | 3.82 | 0.55 | 3.98 | 0.49 | 23 | |

| 1 | I am comfortable with developing my own clinical questions that will help me provide better patient care | 3.38 | 0.90 | 4.13 | 0.59 | 53 **** | 3.25 | 0.94 | 4.04 | 0.62 | 24 ** | 3.83 | 0.65 | 4.00 | 0.60 | 23 |

| 2 | I am familiar with research tools that allow me to retrieve useful clinical information | 3.52 | 0.90 | 4.15 | 0.57 | 52 **** | 3.35 | 0.98 | 4.00 | 0.60 | 23 * | 4.04 | 0.64 | 3.91 | 0.51 | 23 |

| 3 | I am comfortable requesting specialty consultations on behalf of my patients | 3.08 | 0.78 | 3.96 | 0.71 | 53 **** | 2.78 | 0.85 | 4.22 | 0.60 | 23 **** | 3.91 | 0.61 | 4.27 | 0.63 | 22 * |

| 4 | I am comfortable presenting my patients clearly, succinctly and accurately in the wards, the clinic, and in the intensive care unit setting | 3.20 | 0.57 | 3.89 | 0.63 | 51 **** | 3.17 | 0.65 | 4.09 | 0.60 | 23 *** | 3.82 | 0.59 | 4.14 | 0.64 | 22 |

| 5 | I am comfortable with the most common night float calls on the wards, and feel I am appropriately equipped with strategies to respond | 2.28 | 0.72 | 3.43 | 0.97 | 53 **** | 2.13 | 0.74 | 3.65 | 0.91 | 24 **** | 3.52 | 0.85 | 3.63 | 0.93 | 23 |

| Obstetrics & Gynecology (OB) – Overall | 2.60 | 0.67 | 3.43 | 0.87 | 6 ** | 2.60 | 0.85 | 3.50 | 0.99 | 2 | 3.50 | 1.27 | 3.50 | 0.99 | 2 | |

| 1 | I am comfortable writing admission orders for patients with an undifferentiated diagnosis | 1.83 | 0.98 | 2.50 | 1.05 | 6 | 2.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 2.12 | 2 | 3.00 | 1.41 | 3.50 | 2.12 | 2 |

| 2 | I have a better understanding of changes in patient's conditions that require immediate attention | 2.83 | 0.98 | 3.33 | 0.82 | 6 | 2.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| 3 | I have a better comprehension of available sources of help when I'm feeling overwhelmed | 2.17 | 0.41 | 3.67 | 1.03 | 6 ** | 2.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 4.00 | 1.41 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| 4 | I recognize the importance of expanding my differential diagnosis for common disease states | 3.50 | 1.22 | 4.33 | 1.21 | 6 * | 3.00 | 1.41 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 3.50 | 2.12 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| 5 | I am comfortable discussing surgical options with patients and their families | 2.67 | 1.03 | 3.33 | 0.82 | 6 | 2.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 3.50 | 0.71 | 2 |

| Pediatrics - Overall | 2.64 | 0.62 | 3.79 | 0.55 | 21 **** | 2.75 | 0.58 | 3.82 | 0.31 | 17 **** | 3.77 | 0.59 | 3.82 | 0.31 | 17 | |

| 1 | I am comfortable performing an infant lumbar puncture | 2.50 | 0.89 | 3.63 | 0.58 | 20 **** | 2.65 | 0.86 | 3.71 | 0.69 | 17 *** | 3.68 | 0.58 | 3.71 | 0.69 | 17 |

| 2 | I am comfortable performing an intraosseous line | 1.71 | 0.72 | 3.90 | 0.77 | 21 **** | 1.82 | 0.73 | 3.35 | 0.79 | 17 **** | 3.76 | 0.75 | 3.35 | 0.79 | 17 |

| 3 | I am comfortable handling the initial management of a seizure | 2.19 | 0.75 | 3.55 | 0.80 | 21 **** | 2.24 | 0.75 | 3.59 | 0.62 | 17 **** | 3.44 | 0.79 | 3.59 | 0.62 | 17 |

| 4 | I am comfortable handling the initial management of a patient with sepsis | 2.71 | 0.85 | 3.69 | 0.78 | 21 **** | 2.76 | 0.75 | 3.76 | 0.56 | 17 **** | 3.68 | 0.85 | 3.76 | 0.56 | 17 |

| 5 | I am comfortable incorporating feedback into daily practice | 3.19 | 0.81 | 4.00 | 0.84 | 21 *** | 3.29 | 0.85 | 4.06 | 0.66 | 17 ** | 4.00 | 0.87 | 4.06 | 0.66 | 17 |

| 6 | I am comfortable triaging sick vs not sick patients | 2.81 | 0.87 | 3.71 | 0.78 | 21 **** | 2.94 | 0.83 | 3.76 | 0.75 | 17 * | 3.82 | 0.81 | 3.76 | 0.75 | 17 |

| 7 | I am comfortable communicating effectively with patients and families | 3.52 | 0.93 | 3.95 | 0.74 | 21 * | 3.65 | 0.93 | 4.41 | 0.51 | 17 ** | 4.06 | 0.75 | 4.41 | 0.51 | 17* |

| 8 | I am comfortable writing prescription orders | 2.43 | 0.93 | 3.83 | 0.73 | 21 **** | 2.65 | 0.86 | 3.91 | 0.36 | 17 **** | 3.74 | 0.66 | 3.91 | 0.36 | 17 |

| Psychiatry (PSY) - Overall | 3.44 | 0.87 | 4.33 | 0.51 | 13 *** | 3.47 | 0.85 | 4.27 | 0.51 | 7 | 4.41 | 0.55 | 4.27 | 0.51 | 7 | |

| 1 | I am comfortable incorporating feedback into daily practice. | 4.15 | 0.90 | 4.77 | 0.44 | 13 * | 4.00 | 1.00 | 4.43 | 0.53 | 7 | 4.71 | 0.49 | 4.43 | 0.53 | 7 |

| 2 | I am comfortable communicating effectively with patients and families | 3.92 | 0.95 | 4.23 | 0.83 | 13 | 3.86 | 0.90 | 4.57 | 0.53 | 7 | 4.14 | 0.90 | 4.57 | 0.53 | 7 |

| 3 | I am comfortable writing prescription orders. | 2.23 | 1.09 | 3.46 | 1.13 | 13 ** | 2.14 | 1.07 | 4.00 | 0.82 | 7 * | 3.57 | 1.40 | 4.00 | 0.82 | 7 |

| 4 | I am comfortable obtaining a psychiatric review of systems during my patient evaluation | 3.62 | 0.87 | 4.46 | 0.66 | 13 *** | 3.71 | 0.76 | 4.14 | 0.69 | 7 | 4.71 | 0.49 | 4.14 | 0.69 | 7 |

| 5 | I am comfortable obtaining a mental status examination and presenting the findings | 3.69 | 0.95 | 4.54 | 0.52 | 13 ** | 3.86 | 0.90 | 4.29 | 0.49 | 7 | 4.71 | 0.49 | 4.29 | 0.49 | 7 |

| 6 | I am comfortable formulating the psychiatric assessment in the Bio-Psycho-Social-Cultural format. | 3.31 | 0.95 | 4.31 | 0.63 | 13 *** | 3.43 | 0.98 | 4.14 | 0.69 | 7 | 4.43 | 0.53 | 4.14 | 0.69 | 7 |

| 7 | I am comfortable evaluating the patient safety issues in a psychiatric setting. | 3.15 | 1.28 | 4.54 | 0.52 | 13 ** | 3.29 | 1.25 | 4.29 | 0.49 | 7 | 4.57 | 0.53 | 4.29 | 0.49 | 7 |

| Surgery (SUR) - Overall | 3.07 | 0.82 | 3.88 | 0.78 | 41 **** | 2.85 | 0.91 | 3.67 | 0.99 | 17 ** | 3.74 | 0.86 | 3.74 | 1.01 | 18 | |

| 1 | I am comfortable to perform suturing techniques | 3.50 | 1.04 | 4.15 | 0.95 | 40 **** | 3.18 | 1.13 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 17 ** | 3.83 | 1.04 | 4.06 | 1.00 | 18 |

| 2 | I am comfortable to perform basic laparoscopic techniques | 2.54 | 1.02 | 3.62 | 1.09 | 39 **** | 2.31 | 0.79 | 3.19 | 1.17 | 16 * | 3.71 | 0.99 | 3.29 | 1.21 | 17 |

| 3 | I am comfortable to perform airway skill including intubation | 3.15 | 1.20 | 4.00 | 0.95 | 41 **** | 2.88 | 1.36 | 3.76 | 1.39 | 17 ** | 3.75 | 1.14 | 3.83 | 1.38 | 18 |

| 4 | I am comfortable to evaluate and manage a patient scenario (eg abdominal pain, cardiac, respiratory) | 3.12 | 1.03 | 3.83 | 0.86 | 41 **** | 3.12 | 1.32 | 3.71 | 1.16 | 17 * | 3.78 | 0.88 | 3.78 | 1.17 | 18 |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 Note: rating scale = 1–5 scale (1 = no confidence; 3 = some confidence; 5 = complete confidence); na = not applicable; Pre means were not identical and Post 1 means were not identical because the means were derived based on only complete pairs of pre-post data

aGeneral items by specialty – statistically significant differences where n > 5; (-) indicates decrease across time: Pre vs. Post 1

Item 1: FM, IM, PED, SUR Item 2: IM, PED, SUR Item 3: FM, IM, PED, SUR

Pre vs. Post 2:

Item 1: FM, IM, PED, SUR

Item 2: IM

Item 3: FM, IM, PED, SUR

Post 1 vs. Post 2

Item 1: none

Item 2: IM(-)

Item 3: IM

Procedures

The evaluation of the boot camp involved surveying each medical student just prior to the first day of the boot camp (Pre), immediately after the last day of the boot camp (Post 1), and 3 months after the participants started his or her residency training (Post 2). Written consent was obtained from the students to complete surveys as part of the study. All 4th year students were allowed to participate in the boot camp, regardless of their participation in the study. Two students declined to participate in the study but completed the boot camp. Paper surveys were administered in the morning before the first day of the boot camp and in the afternoon following the final day of the boot camp. Electronic Post 2 surveys were administered to the participants 3 months after they started residency training. Code names were assigned by the principal investigator and, after initial distribution to the students, were kept in a locked office. Codes were used to maintain the anonymity of the medical students and to link the anonymous data across time. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

Data Analysis

For each item and composite score across each of the three time periods (Pre, Post, Post 2), the mean, standard deviation, and sample size were computed. Dependent sample t-tests were employed to determine whether there were statistically significant differences among (1) Pre vs. Post; (2) Pre vs. Post 2; and (3) Post vs. Post 2. In addition, for the three general items that included pre-post differences, t-tests were conducted within each specialty. The alpha level was set at 0.05. In addition, effect size was computed for the 3 general questions and the specialty-specific composite scores for Pre-Post.

Results

The integrated approach of a school-wide boot camp was effective as student confidence levels increased significantly across all subspecialties (overall) immediately after the boot camp (Table 2). In particular, confidence levels increased for all parameters for the subspecialties of Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Surgery, 6 of 7 items for Psychiatry, 2 of 5 parameters for Obstetrics and Gynecology, and 5 of 8 parameters for Emergency Medicine.

After completing the boot camp, the confidence level rating increased significantly for the following questions: 1) I am prepared to function as an intern; 2) I can communicate with patients effectively; and 3) A 3-day-long intern prep course is worthwhile. Additionally, the Pediatric (Question #8) and Psychiatry (Question #3) students significantly increased their confidence level rating for “I am comfortable writing prescription orders.”

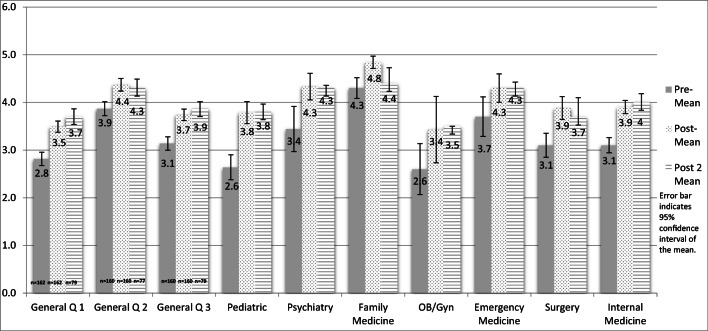

The effect sizes for the specialty-specific composites and 3 general questions were moderate to large ranging from 0.55 to 1.97. The increases in the confidence levels in the general and specialty-specific composite items can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Mean student confidence levels Pre, Post, and Post 2 survey results after completion of the workshop

Only 45% of surveys were returned 3 months after the boot camp, and statistical comparisons were more difficult because of the small sample size (e.g., only 2 were received for Emergency Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynecology). However, where the sample size was larger (i.e., > 10), such as Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Surgery, the increased confidence level was recognized 3 months after the boot camp. This finding suggested that the effect may have been maintained across the 3 month period but could not be fully detected due to small sample sizes.

Conclusion

Overall, there were statistically significant positive increases in confidence for the general and specialty-specific items and composites. This overall pattern was stronger for the Pre-Post comparisons and for specialties that entailed larger sample sizes. The latter was expected given that p values are more statistically significant with larger sample sizes; all other things equal (e.g., mean differences, variances). Moderate to large effect sizes were found.

This investigation fills the gap in the published literature on teaching medical students transitioning to residency via a boot camp program with the important outcome of student confidence. While a few schools utilize an integrated school-wide boot camp, this is the first published study that involved the development of an integrated, school-wide approach for a medical school boot camp program. Due to the integrated approach in the creation of this boot camp, every student in our school was able to participate in this boot camp. In addition, the boot camp experience was tailored to everyone’s needs as it had common sessions with topics applicable to EPAs needed for all medical student graduates as well as specialty-specific sessions that focused on their specialty milestone.

Limitations

There were several limitations for the present study: (1) We did not measure actual application of increased self-reported confidence and did not report in this study other meaningful outcomes, such as future residency performance. Future research should examine these aspects more fully. (2) The survey was not validated through factor analysis because of the small sample size. However, the overall pattern of statistically significant findings suggested reliability and validity of the survey. (3) The p values of the specialty comparisons appeared to be highly dependent upon the sample size, as would be expected. However, despite this, there were statistically significant differences found for comparisons with relatively small sample sizes due to the moderate to large effect sizes. (4) The Pre, Post 1, and Post 2 means in Table 2 were based on only complete pairs of pre-post data, thus resulting in, for example, the two pre means not being identical and the possibility of some bias due to attrition. (5) Alpha was set at 0.05 despite the number of comparisons made. Alpha was set at this level because of the relatively small sample sizes (i.e., low statistical power). However, 46 of the 53 (87%) of the Pre-Post comparisons were statistically significant indicating that the overall pattern did not occur by chance. (6) The 3-month participation rate was 46% (75/162). Although this rate could be considered to be an adequate participation rate for busy residents, we are uncertain of the bias that this might have contributed. (7) The 3-month Post 2 evaluation may have been confounded with residency training that may have diminished the long-term impact of the boot camp. Future research should examine this possible confounding by surveying the medical students prior to residency training as well as to determine how residency internship overlaps with the content covered by the boot camp. And (8) the dissipating effects across the 3-month period may suggest decreased statistical power due to attrition, the need for “booster” interventions, and/or overlapping content with residency internship training.

Implications

The overall empirical results support maintaining the boot camp. In addition, a case could be made for cautious but wide generalization and permanence of such educational interventions for medical schools. Many schools, particularly in preparation for surgical residency programs, have developed individualized boot camp or capstone programs for their students preparing to enter residency [17, 18]. The benefits of individualized boot camp preparation courses for students in different specialties have been documented [19, 20]. However, an integrated approach to the development of a capstone course is a novel one. Given the effect sizes were moderate to large, the students had a significant increase in their confidence level in measured boot camp items. In addition, the students improved confidence in skills that the literature has shown incoming interns to fall below expectations in communication skills for all students and prescription writing in the Pediatric and Psychiatry students. While an integrated school-wide workshop requires more planning and coordination efforts than individual subspecialty workshops, the integrated approach can circumvent difficulty obtaining faculty volunteers to teach workshops for all students. For example, the suture workshop was taught by the OB/GYN and Surgery faculty. However, the Surgery, OB/GYN, Family Medicine, and Emergency Medicine medical students were able to benefit from this single workshop. The school-wide integrated approach also increased substantially the likelihood that all students would receive preparation rather than only specific specialties that offered the boot camp. An inclusive boot camp to train students entering multiple specialties has value to a medical student curriculum, as seen by the increase in student confidence levels in post-survey 1. If the boot camp curriculum was developed for only specific specialties, then students entering other specialties would have felt left out. This program was able to allow participation of all students and provide them a specialty-specific curriculum. Additionally, in an era of “do more with less,” the integrated approach provides training for more medical students requiring fewer resources per student.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge our fellow clerkship directors who helped to develop the curriculum for this novel integrated boot camp: Dr. Sheldon Riklon, Dr. Damon Lee, Dr. Gregory Suares, Dr. Lawrence Burgess, Dr. Christie Izutsu, Dr. Mari Shiraishi, Dr. Susan Steinemann, and Dr. Chad Cryer.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict(s) of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Milestones. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf?ver=2016-05-31-113245-103. Accessed 15 Mar 2019

- 2.Assoc. of American Medical Coll. (AAMC). Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. Available at: https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Core%20EPA%20Faculty%20and%20Learner%20Guide.pdf Accessed 15 Mar 2019

- 3.Lindeman BM, Sacks BC, Lipsett PA. Graduating students’ and surgery program directors’ views of the association of American colleges core entrustable professional activities for entering residency: where are the gaps? J Surg Educ. 2015;72:e184–e192. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyss-Lerman P, Tehrani A, Aagaard E, Loeser H, Cooke M, Harper GM. What training is needed in the fourth year of medical school? Views of residency program directors. Acad Med. 2009;84:823–829. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a82426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K, Cameron HS. Are medical graduate ready to face the challenges of foundation training? Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:590–595. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2010.115659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce AN, Kumar A, Malekzadeh S. Procedural skills of the entrustable professional activities: are graduating US medical students prepared to perform procedures in residency? Journal Surg Educ. 2017;74:589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lypson ML, Frohna JG, Gruppen LD, Woolliscroft JO. Assess residents’ competencies at baseline: identifying the gaps. Acad Med. 2004;79:564–570. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matheson C, Matheson D. How well prepared are medical students for their first year as doctors? The views of consultants and specialist registrars in two teaching hospitals. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:582–589. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.071639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilmer SN, Seale JP, Le Couteur DG, Crampton R, Liddle C. Do medical courses adequately prepare interns for safe and effective prescribing in New South Wales public hospitals? Intern Med J. 2009;39:428–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laack TA, Newman JS, Gayal DG, Torsher LC. A 1-week simulated internship course helps prepare medical students for transition to residency. Simul Healthc. 2010;5:127–132. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181cd0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esterel RM, Henzi DL, Cohn SM. Senior medical student “boot camp”: can result in increased self-confidence before starting surgery internships. Curr Surg. 2006;63:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wayne DB, Cohen ER, Singer BD, Moazed F, Barsuk JH, Lyons EA, Butter J, McGaghie WC. Progress toward improving medical school graduates’ skill via a “boot camp” curriculum. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(1):33–39. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krajewski A, Filippa D, Staff I. Singh R, Kirton OC. Implementation of an intern boot camp curriculum to address clinical competencies under the new accreditation council for graduate medical education supervision requirements and duty hour restrictions. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(8):727–732. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontes RB, Selden NR, Byrne RW. Fostering and assessing professionalism and communication skills in neurosurgical education. J of Surg Educ. 2014;71:e83–e89. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen T, Beier-Holdersen R, Ostergaard D, Dieckmann P. Training residents to lead emergency teams: a qualitative review of barriers, challenges and learning goals. Heliyon. 2018;12:e01037. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonoff MB, Swanson JA, Green CA, Mann BD, Maddaus MA, D’Cunha J. The significant impact of a competency-based preparatory course for senior medical students entering surgical residency. Acad Med. 2012;87:308–319. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318244bc71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neylan CJ, Nelson EF, Dumon KR, Morris JB, Williams NN, Dempsey DT, Kelz RR, Fisher CS, Allen SR. Medical school surgical boot camps: a systematic review. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns R, Alder M, Mangold K, Trainor J. A brief boot camp for 4th-year medical students entering into pediatric and family medicine residencies. Cureus. 2016;8:e488. doi: 10.7759/cureus.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackmore C, Austin J, Lopushinsky SR, Donnon T. Effects of postgraduate medical education “boot camps” on clinical skills, knowledge, and confidence: a meta-analysis. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:643–645. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00373.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]