Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to establish the contribution of PALB2 mutations to prostate cancer risk and to estimate survival among PALB2 carriers.

Methods

We genotyped 5472 unselected men with prostate cancer and 8016 controls for two Polish founder variants of PALB2 (c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT). In patients with prostate cancer, the survival of carriers of a PALB2 mutation was compared to that of non-carriers.

Results

A PALB2 mutation was found in 0.29% of cases and 0.21% of controls (odds ratio (OR) = 1.38; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70–2.73; p = 0.45). PALB2 mutation carriers were more commonly diagnosed with aggressive cancers of high (8–10) Gleason score than non-carriers (64.3 vs 18.1%, p < 0.0001). The OR for high-grade prostate cancer was 8.05 (95% CI 3.57–18.15, p < 0.0001). After a median follow-up of 102 months, the age-adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause mortality associated with a PALB2 mutation was 2.52 (95% CI 1.40–4.54; p = 0.0023). The actuarial 5-year survival was 42% for PALB2 carriers and was 72% for non-carriers (p = 0.006).

Conclusion

In Poland, PALB2 mutations predispose to an aggressive and lethal form of prostate cancer.

Subject terms: Risk factors, Molecular medicine, Prostate cancer

Background

Prostate cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in men worldwide.1 Genetic susceptibility plays an important role in prostate cancer risk. About 10–20% of cases occur in a familial setting.2 Based on a recent study of twin pairs, prostate cancer heritability is estimated to be 57%.3 High heritability can be explained by a combination of polygenic inheritance (multiple low-risk loci) and the inheritance of rare high-risk mutations in susceptibility genes, including BRCA2, HOXB13, BRCA1, CHEK2, NBN, ATM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2.4–10 Most genes associated with a predisposition to prostate cancer play a role in DNA damage repair.

PALB2 (accession number NM_024675.3) encodes a BRCA2-binding protein that acts as a linker between BRCA1 and BRCA2 to form a BRCA1-associated genome surveillance complex. The complex is essential for the homologous DNA break repair.11 Homozygous mutations of PALB2 cause Fanconi anaemia,12 a rare recessive chromosomal breakage syndrome characterised by physical abnormalities, bone marrow failure and a high risk of malignancy. Heterozygous carriers of PALB2 mutations are at increased risk of breast, pancreatic and ovarian cancers.13

In Poland, there are two PALB2 founder mutations (c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT), which account for ~80% of all PALB2 mutations detected in the population.14 Both are localised in the 5′ end of the PALB2 gene. The c.509_510delGA (p.R170Ifs*14) and the c.172_175delTTGT (p.Q60Rfs*7) variants cause a translational frameshift with a predicted alternate stop codon, and are expected to result in the loss of PALB2 function by premature protein truncation or nonsense-mediated messenger RNA decay. There is a clear evidence that the two Polish founder mutations of PALB2 are pathogenic for breast cancer. In a large study of 12,529 women with unselected breast cancer and in 4702 controls from Poland, the odds ratio (OR) for breast cancer given the c.509_510delGA mutation was 4.09 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.89–8.88; p = 0.0004), and for the c.172_175delTTGT mutation it was 5.02 (95% CI 1.55–16.2; p = 0.007).15 We found that the prognosis of breast cancer associated with a PALB2 mutation to be poor.15 The two Polish founder mutations of PALB2 were also seen in excess in 383 cases of pancreatic cancer compared to cancer-free controls, but the difference was not significant (OR 2.61, 95% CI 0.55–12.34).16 These two variants were associated with a 3-fold increased risk of unselected ovarian cancer in Poland (OR 3.34; 95% CI 1.06–14.68).17

BRCA2 is a clear prostate cancer susceptibility gene and BRCA2 mutations are associated with poor prognosis.18 BRCA2 protein directly interacts with PALB2 protein; therefore, we reasoned that PALB2 is a good candidate gene for prostate cancer susceptibility. Prostate cancer risk in PALB2 carriers has not been extensively studied.19 To establish the contribution of PALB2 mutations to the burden of prostate cancer in Poland, we genotyped 5472 men with prostate cancer and 8016 controls for two recurrent mutations of PALB2 (c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT).

Methods

Patients

We included 5472 men with unselected prostate cancer who were diagnosed between 1999 and 2015 in 14 centres throughout Poland. This study was initiated in Szczecin in 1999 and was extended to include Białystok, Olsztyn in 2002 and Opole in 2003. Other centres began recruiting between 2005 and 2008 (Koszalin, Gdansk, Lublin, Łodź, Warszawa, Wrocław, Poznan, Rzeszów, Bydgoszcz and Zabrze). Men with newly diagnosed, untreated prostate cancer were invited to participate. Prostate cancer cases enrolled in the study are unselected for age, clinical characteristics (stage, grade, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level at the time of diagnosis), family history or treatment. Study subjects were asked to participate at the time of diagnosis. The patient participation rate was 85.4%. Patients who provided a blood sample within 6 months of diagnosis were enrolled. Men who provided blood sample above 6 months from diagnosis (n = 51) were excluded. The mean age of diagnosis was 67.8 years (range 35–96 years). A family history was taken either by the construction of a family tree or the completion of a standardised questionnaire. All first- and second-degree relatives diagnosed with prostate cancer and the ages of diagnosis were recorded. Family history was available for 4557 of the men (83.4%) with prostate cancer. Six hundred and fifty-seven of 4557 men (14.4%) reported at least one first- or second-degree relative with prostate cancer. In addition, information was recorded on PSA level at the time of diagnosis, grade (Gleason score) and stage. The vital status (dead or alive) and the date of death were requested from the Polish Ministry of the Interior and Administration in June 2016 and were obtained in July 2016. Survival data were available for 5446 men (99.5%) with prostate cancer.

Controls

Controls included 8016 cancer-free adults from the genetically homogeneous population of Poland. The control group consisted of 3314 cancer-free men aged 23–90 years (mean age, 62.2 years) and 4702 cancer-free women aged 18–94 years (mean age, 54.0 years) described previously.20,21 The purpose of the control group was to estimate with accuracy the frequency of founder alleles of PALB2 in the underlying Polish population. The allele frequencies for PALB2 variants in controls were not dependent on age and sex. The frequency of PALB2 mutations in male and female controls was the same (0.21%). All cases and controls were ethnic Poles. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, Poland.

Genotyping

All subjects were genotyped for two Polish founder mutations c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT. DNA was isolated from 5 to 10 ml of peripheral blood. PALB2 mutations were genotyped using TaqMan assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using LightCycler® Real-Time PCR 480 System (Roche Life Science). Laboratory technicians were blinded to case–control status. The presence of the mutations was confirmed by Sanger direct sequencing. Sequencing reactions were performed using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Loss of heterozygosity analysis

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples from four PALB2 mutation carriers were available in the Department of Pathology of Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin. We had access only to core biopsies with a limited amount of cancer tissue. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis at the PALB2 locus was performed in DNA from micro-dissected tumours from four PALB2 mutation-positive men using the methodology described previously8 with some modifications: (1) DNA was isolated with QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (from Qiagen); (2) LOH was analysed by direct Sanger sequencing of 101 bp DNA fragment containing the c.509_510delGA mutation (forward primer, 5′-CAGAAGAGGACATTTATTTCACAG; reverse primer, 5′-CTACTGATTTCTTCCTGTTCCTTTAG), and 92 bp DNA fragment containing the c.172_175delTTGT mutation (forward primer, 5′-CCCAAAGAGCTGAAAAGATTAAG; reverse primer, 5′-TTTTAGCTGCGGTGAGAGAT).

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of the deleterious PALB2 alleles was estimated in prostate cancer cases and population controls. ORs were generated from two-by-two tables and statistical significance was assessed using the Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test where appropriate. Men with prostate cancer, with and without a PALB2 mutation, were compared for age at diagnosis, family history and clinical features of the prostate cancers. Means were compared using t test, and medians were compared using Mann–Whitney test.

To estimate actuarial survival, a Kaplan–Meier curve was constructed. Men were followed from the date of diagnosis (the date of biopsy) until the date of death or July 2016. The vital status was available for 5446 (99.5%) of men with prostate cancer. The crude hazard ratio (HR) for death (all-cause mortality), given a PALB2 mutations, was estimated using the Cox proportional hazards model. The data were re-analysed, adjusting for age of diagnosis for all 5446 cases with prostate cancer.

Detailed clinical information was available for a subset of 2101 patients, including the age of diagnosis, PSA level at diagnosis, tumour stage and Gleason score and PALB2 mutation status. A multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed on this subset of patients.

Results

All subjects were genotyped for two Polish founder alleles (c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT). A PALB2 mutation was present in 16 of 5472 unselected cases (0.29%) and in 17 of 8016 cancer-free controls (0.21%). The OR for unselected prostate cancer given a PALB2 mutation was 1.38 (95% CI 0.70–2.73) and was not statistically significant (p = 0.45). A PALB2 mutation was detected in one (0.15%) of 657 men with familial prostate cancer compared to 0.21% of 8016 cancer-free controls; the OR was not significant (OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.10–5.40, p = 0.75). The mutation prevalence was 0.30% for men diagnosed below age 60 years, 0.29% for men diagnosed between the ages 60–70 years and 0.30% for men diagnosed above age 70 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of PALB2 mutations (c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT) in prostate cancer cases and controls.

| Category | N total | N positive | % | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unselected cases | ||||||

| c.509_510delGA | 5472 | 8 | 0.15% | 1.07 | 0.43–2.65 | 0.89 |

| c.172_175delTTGT | 5472 | 8 | 0.15% | 1.96 | 0.67–5.64 | 0.32 |

| Any PALB2 mutation | 5472 | 16 | 0.29% | 1.38 | 0.70–2.73 | 0.45 |

| Familial cases | ||||||

| c.509_510delGA | 657 | 1 | 0.15% | 1.11 | 0.14–8.61 | 0.92 |

| c.172_175delTTGT | 657 | 0 | 0.00% | — | — | 0.48 |

| Any PALB2 mutation | 657 | 1 | 0.15% | 0.72 | 0.10–5.40 | 0.75 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| <60 | 1011 | 3 | 0.30% | 1.40 | 0.41–4.79 | 0.85 |

| 60–70 | 2436 | 7 | 0.29% | 1.36 | 0.56–3.27 | 0.66 |

| >70 | 2025 | 6 | 0.30% | 1.40 | 0.55–3.55 | 0.65 |

| Controls | ||||||

| Males | ||||||

| c.509_510delGA | 3314 | 4 | 0.12% | |||

| c.172_175delTTGT | 3314 | 3 | 0.09% | |||

| Females | ||||||

| c.509_510delGA | 4702 | 7 | 0.15% | |||

| c.172_175delTTGT | 4702 | 3 | 0.06% | |||

| All controls | ||||||

| c.509_510delGA | 8016 | 11 | 0.14% | |||

| c.172_175delTTGT | 8016 | 6 | 0.07% | |||

| Any PALB2 mutation | 8016 | 17 | 0.21% | Ref. | — | — |

Familial cases refer to two or more prostate cancers in first- or second-degree relatives (including proband). Odds ratios and p values are calculated with respect to cancer-free controls as a reference.

The characteristics of the prostate cancers in men with and without a PALB2 founder mutation are presented in Table 2. There was no difference in the mean age of onset in mutation carriers and non-carriers (68.3 vs 67.3 years, p = 0.65). The median PSA value at the time of diagnosis was higher in carriers than in non-carriers (21.2 vs 10.7 ng/ml, p = 0.0059); 57.1% of carriers had a PSA level >20 ng/ml vs 28.2% of non-carriers (p = 0.036). PALB2 mutation carriers were more commonly diagnosed with high-grade (Gleason score 8–10) prostate cancers than were non-carriers (64.3 vs 18.1%, p < 0.0001). There were nine PALB2 mutation carriers among the 535 men with Gleason score 8–10 cancers (OR = 8.05, 95% CI 3.57–18.15, p < 0.0001, compared to cancer-free controls). Among the 535 men with Gleason score 8–10 tumours, three carried the c.509_510delGA mutation (compared to 11 of 8016 cancer-free controls; OR = 4.10, 95% CI 1.14–14.76) and six carried the c.172_175delTTGT mutation (compared to 6 of 8016 cancer-free controls; OR = 15.14, 95% CI 4.87–47.12). In contrast, there was only one carrier of a PALB2 mutation in 1576 men with prostate cancer of Gleason score below 7 (OR = 0.30, 95% CI 0.04–2.25, p = 0.35, compared to cancer-free controls).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with PALB2 mutation-positive and mutation-negative prostate cancer.

| Category | PALB2 mutation-positive cases (n = 16) | PALB2 mutation-negative cases (n = 5456) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of diagnosis | |||

| Mean (range) | 68.3 (52–78) | 67.3 (35–93) | 0.65 |

| <60 | 18.8% (3/16) | 18.5% (1008/5456) | 0.98 |

| 61–70 | 43.8% (7/16) | 44.5% (2429/5456) | 0.95 |

| >70 | 37.5% (6/16) | 37.0% (2019/5456) | 0.97 |

| PSA at diagnosis | |||

| Median (range) | 21.2 (7.3–243.5) | 10.7 (0.1–5000) | 0.0059 |

| ≤4.0 | 0.0% (0/14) | 5.7% (146/2542) | 0.73 |

| 4.1–10 | 14.3% (2/14) | 41.6% (1058/2542) | 0.072 |

| 10.1–20.0 | 28.6% (4/14) | 24.4% (621/2542) | 0.96 |

| >20.0 | 57.1% (8/14) | 28.2% (717/2542) | 0.036 |

| Gleason score | |||

| <7 | 7.1% (1/14) | 54.1% (1575/2913) | 0.0012 |

| 7 | 28.6% (4/14) | 27.9% (812/2913) | 0.95 |

| >7 | 64.3% (9/14) | 18.1% (526/2913) | <0.0001 |

| Stage | |||

| T1/2 | 64.3% (9/14) | 75.1% (1658/2209) | 0.54 |

| T3/4 | 35.7% (5/14) | 24.9% (551/2209) | 0.54 |

| Family history of prostate cancer | |||

| Positive | 6.3% (1/16) | 14.4% (656/4541) | 0.57 |

p Values are calculated with respect to non-carriers as a reference group. Family history refers to one or more prostate cancers in first- or second-degree relatives.

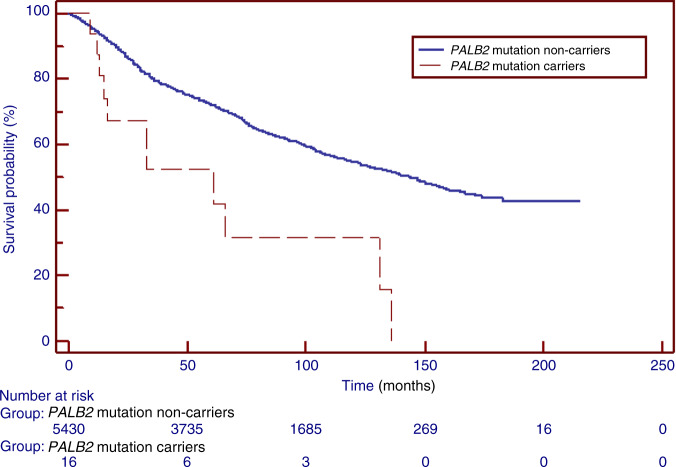

The median duration of follow-up was 102 months. There were 2230 deaths from all causes among 5430 non-carriers (41.1%) and there were 11 deaths among the 16 PALB2 mutation carriers (68.8%; p = 0.046). The actuarial 5-year all-cause survival for PALB2 carriers was 42 vs 72% for non-carriers (p = 0.006). The 10-year all-cause survival was 31% for PALB2 carriers vs 55% for non-carriers (p = 0.01) (Table 3) (Fig. 1). The unadjusted HR for death associated with the presence of a PALB2 mutation was 2.74 (p = 0.0008). After adjusting for age at diagnosis, the HR associated with a PALB2 mutation was 2.52 (95% CI 1.40–4.54; p = 0.0023).

Table 3.

Survival of men with a PALB2 mutation and in non-carriers.

| Cases with PALB2 mutation, n = 16 | Mutation-negative cases, n = 5430 | |

|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up | 96 | 102 |

| Proportion of deceased | 68.8% (11/16) | 41.1% (2230/5430) |

|

Median survival |

61 | 144 |

|

5-Year survival |

42% | 72% |

|

10-Year survival |

31% | 55% |

| Crude HR | 2.74 | Ref. |

| 95% CI | 1.52–4.95 | |

| p Value | 0.0008 | |

| Age-adjusted | ||

| HR | 2.52 | Ref. |

| 95% CI | 1.40–4.54 | |

| p Value | 0.0023 |

Follow-up is calculated from diagnosis to end of the survival study (July 2016). HR, 95% CI and p value are calculated by the Cox proportional hazards model.

Fig. 1. Kaplan–Meier curves of prostate cancer patients with a PALB2 mutation, compared with mutation-negative prostate cancer patients (non-carriers).

PALB2 mutation non-carriers—men with prostate cancer who tested negative for PALB2 c.509_510delGA and c.172_175delTTGT mutations. PALB2 mutation carriers—men with prostate cancer who tested positive for PALB2 c.509_510delGA or c.172_175delTTGT mutation.

Cause of death was available for 9 of the 11 men with prostate cancer and a PALB2 mutation. Of the nine patients with the cause of death available, seven (78%) died of prostate cancer, one (11%) died of pancreatic cancer and one (11%) died from a non-cancer-related cause. Of the seven men with a PALB2 mutation who died of prostate cancer, three had the c.509_510delGA mutation and four had the c.172_175delTTGT mutation.

In a subset analysis including 2101 men with detailed clinical information, the adjusted HR associated with a PALB2 mutation was 1.78 (95% CI 0.96–3.32, p = 0.069). This analysis was adjusted for age of diagnosis, Gleason score, stage and PSA level. We also did a separate analysis in which we adjusted for Gleason score (>7 vs ≤7) and PSA level (>20 vs ≤20 ng/ml). In this analysis of 2378 men with prostate cancer, the adjusted HR associated with a PALB2 mutation was 1.99 (95% CI 1.07–3.71, p = 0.031).

To investigate if men with prostate cancer and a PALB2 mutation carry other prostate cancer-predisposing mutations, we screened the entire coding sequence of BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 and CHEK2 in the 16 PALB2 mutation carriers with prostate cancer (using NGS Agilent SureMASTER BRCA Screen Kit, and Illumina Miniseq), and also genotyped the 16 carriers for the presence of HOXB13 G84E founder mutation and the NBN 657del5 founder mutation (using TaqMan-PCR). Neither carrier of a PALB2 mutation tested positive for mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, NBN or HOXB13 genes.

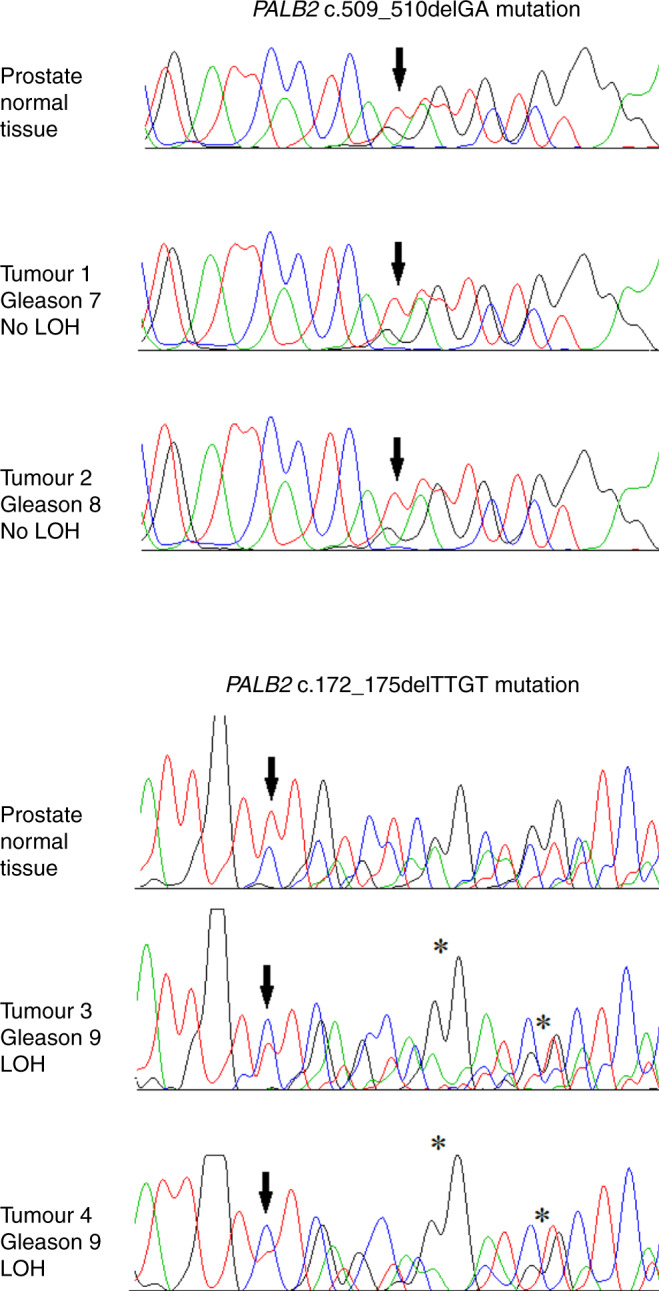

We analysed tumour DNA of four men with a PALB2 mutation for LOH using Sanger sequencing of short fragments (of ~100 bp) containing the two PALB2 mutations. Although Sanger sequencing is not an ideal method for LOH study, two of the four tumour DNA samples showed an increased ratio of the mutated allele vs normal allele (compared to the ratio seen in normal prostate tissues), which suggested the existence of LOH (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) analysis in prostate cancer tissues and normal tissues from four carriers of a PALB2 mutation; retention of the wild-type PALB2 allele is seen in two tumours; two tumours probably have loss of the wild-type PALB2 allele (best shown by asterisks).

PALB2 mutations are indicated by an arrow (↓). On chromatograms green peaks correspond to nucleotide A, red peaks to nucleotide T, black peaks to nucleotide G, and blue peaks to nucleotide C.

Discussion

In this study of 5472 unselected patients with prostate cancer and 8016 controls, we failed to find an increased risk of prostate cancer associated with truncating PALB2 mutations (OR = 1.38; p = 0.45). However, we found that PALB2 mutations were associated with high-grade prostate cancer. The OR for Gleason 8–10 prostate cancers was 8.05 (95% CI 3.57–18.15, p < 0.0001) compared to cancer-free controls. High Gleason grade was seen in 64% of carriers vs 18% of non-carriers (p < 0.0001). This suggests that PALB2 mutations predispose specifically to aggressive prostate cancers.

Early studies did not identify an association of PALB2 loss-of-function mutations with unselected and familial prostate cancer risk.22,23 Matejcic et al. sequenced PALB2 in men of African Ancestry and detected pathogenic variants in only 4 out of 2098 prostate cancer cases compared to none of 1481 controls (p = 0.03).24 In a study from the United Kingdom, which included 1281 early-onset cases and 1160 selected controls, no pathogenic PALB2 mutations were reported.25 An international study from the Prostate Cancer Association Group to Investigate Cancer Associated Alterations in the Genome (PRACTICAL) genotyped 22,301 European men with prostate cancer and 22,320 controls for two protein-truncating PALB2 variants; neither was associated with a significantly increased risk.26 A recent large study of 524 prostate cancer families from 21 countries, all with a PALB2 pathogenic variant, reported the estimated risk ratio for prostate cancer to be 0.42 (95% CI 0.21–0.84).13

It is perhaps not surprising that the overall incidence of prostate cancer is not increased among PALB2 carriers, if they mostly develop very aggressive disease, and aggressive tumours constitute the minority of prostate cancer cases in the general population. It is notable that a PALB2 mutation was associated with a lower risk of low-grade prostate cancer (Gleason below 7), albeit not significant. It is possible that PALB2 is not associated with prostate cancer susceptibility, but predisposes to an aggressive phenotype among those who develop it, that is, in the presence of a PALB2 mutation an otherwise non-aggressive prostate cancer acquires aggressive features. In support of this hypothesis, others have suggested an association of PALB2 with aggressive or metastatic prostate cancer. Wu and colleagues reported PALB2 mutations in two of 706 (0.28%) high-grade tumours compared to one of 988 (0.10%) low-grade cancers (OR 2.80, 95% CI 0.15–165.43), p = 0.57).27 Pritchard et al. found a PALB2 mutation in three of 692 men with metastatic prostate cancer (OR = 3.5, 95% CI = 0.7–10.3, p = 0.05) compared to cancer-free controls in the Exome Aggregation Consortium.28 Leongamornlert et al. identified a single PALB2 deleterious mutation in a man with metastatic disease from the United Kingdom. In this study, all 191 men had three or more cases of prostate cancer in their family.29 In the largest study to date of 5545 men with prostate cancer, 18 of 2770 aggressive cases (0.65%) and three of 2775 of non-aggressive cases (0.11%) carried PALB2 mutations (OR = 6.31, 95% CI 1.83–21.7).30

Our study is the first to provide evidence that the aggressive features of the prostate cancers in PALB2 carriers adversely affect their survival and the first to estimate survival rates for men with prostate cancer and a PALB2 mutation. Forty-two percent of the patients with mutations died within 5 years of diagnosis (compared to 72% in non-carriers, p = 0.006). The mean survival was 61 months in carriers, vs 144 months in non-carriers, and after adjusting for age, the HR for death was 2.5 (95% CI 1.4–4.5). After adjustment for age, grade, stage and PSA, the HR for the PALB2-associated cancers was 1.8 (95% CI 0.96–3.3, p = 0.07).

We have previously reported poor survival for women with breast cancer and a PALB2 mutation.15 Breast cancer patients who carried one of the two Polish PALB2 founder mutations had a 10-year survival of 48%, compared to 75% for patients with breast cancer without a PALB2 mutation (HR = 2.27, 95% CI 1.64–3.15; p < 0.0001). Studies from Finland and China also reported relatively poor survival of PALB2-associated breast cancer patients.31,32 So, the evidence is growing that PALB2 mutations predispose to both poor prognosis breast and prostate cancer.

The principal strength of our study is that it is large and population-based. Cancer patients were unselected for family history. Clinical information data was collected for the majority of PALB2 carriers and we are able to establish the date of death from the national vital statistics database. We studied the impact of two mutations in one country (Poland) and it is possible that the risk estimates and survival may differ by specific mutation or by country of residence.

It is important to determine if men with prostate cancer and a PALB2 mutation may benefit from therapy beyond the standards of radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy. In a recent study, among prostate cancer patients with an alteration in BRCA1, BRCA2 or ATM, progression-free survival was significantly longer in men treated with the PARP inhibitor olaparib than in a control group.33 Sensitivity of PALB2-related prostate cancers to chemotherapy has not been studied, but a dramatic response to PARP inhibition in a PALB2-mutated metastatic breast cancer was recently reported.34

We were able to perform LOH analysis in four PALB2 mutation carriers with prostate cancer. Loss of the wild allele was seen in two tumour samples, and notably, both tumours with LOH had Gleason score of 9. These data suggest that the mechanism of carcinogenesis in the prostate and poor prognosis associated with a PALB2 mutation may be due to the classic Knudsen two-hit hypothesis, but further studies are needed.

In conclusion, PALB2 mutations predispose to an aggressive and lethal form of prostate cancer. In our study, <50% of men with prostate cancer and a PALB2 mutation were alive at 5 years. Given the high case fatality associated with PALB2, we believe it is justified to include PALB2 to the testing panels both for breast and for prostate cancer, in particular for patients with aggressive/metastatic disease. Studies of the use of chemotherapy in the treatment of all PALB2-associated cancers are warranted.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daria Zanoza and Ewa Putresza for their help with managing databases.

Members of the Polish Hereditary Prostate Cancer Consortium

Bartłomiej Masojć8, Adam Gołąb9, Bartłomiej Gliniewicz10, Andrzej Sikorski9, Marcin Słojewski9, Jerzy Świtała10, Tomasz Borkowski11, Andrzej Borkowski11, Andrzej Antczak12, Łukasz Wojnar12, Jacek Przybyła13, Marek Sosnowski13, Bartosz Małkiewicz14, Romuald Zdrojowy14, Paulina Sikorska-Radek15, Józef Matych15, Jacek Wilkosz16, Waldemar Różański16, Jacek Kiś17, Krzysztof Bar17, Piotr Bryniarski18, Andrzej Paradysz18, Konrad Jersak19, Jerzy Niemirowicz19, Piotr Słupski20, Piotr Jarzemski20, Michał Skrzypczyk21, Jakub Dobruch21, Michał Puszyński9, Michał Soczawa9, Mirosław Kordowski10, Marcin Życzkowski18, Andrzej Borówka21, Joanna Bagińska22, Kazimierz Krajka22, Małgorzata Stawicka23, Olga Haus24, Hanna Janiszewska24, Agnieszka Stembalska25, Maria Małgorzata Sąsiadek25.

Author contributions

D.W. designed the study, analysed the study data and drafted the manuscript. W.K., K.S., B.R., K.G. and S.M. selected and prepared DNA samples for genotyping and performed genotyping. T.H., J.G., T.D., M.S. and C.C. enrolled patients and controls for the study, and collected phenotypic data for the study. A.K. performed statistical analyses. W.K. and A.J. performed NGS sequencing. P.D. selected, prepared and provided tissue samples and performed LOH analysis. M.R.A. performed bioinformatics analysis of NGS sequencing data and assisted in drafting the manuscript. S.A.N. and J.L. assisted in coordination of the study and in drafting the manuscript. C.C. conceived, designed and coordinated the study and assisted in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin (IRB No. KB-0012/97/17). Patient clinical data have been obtained in a manner conforming with IRB ethical guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability

The main research data supporting the results of this study are included in Tables 1–3 and Figs. 1 and 2. Other data can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Competing interests

S.N. is an editorial board member for the British Journal of Cancer. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

This study was funded by National Science Centre, Poland; project number: 2015/19/B/NZ2/02439.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the Polish Hereditary Prostate Cancer Consortium are listed above Acknowledgements.

Contributor Information

Cezary Cybulski, Email: cezarycy@pum.edu.pl.

the Polish Hereditary Prostate Cancer Consortium:

Bartłomiej Masojć, Adam Gołąb, Bartłomiej Gliniewicz, Andrzej Sikorski, Marcin Słojewski, Jerzy Świtała, Tomasz Borkowski, Andrzej Borkowski, Andrzej Antczak, Łukasz Wojnar, Jacek Przybyła, Marek Sosnowski, Bartosz Małkiewicz, Romuald Zdrojowy, Paulina Sikorska-Radek, Józef Matych, Jacek Wilkosz, Waldemar Różański, Jacek Kiś, Krzysztof Bar, Piotr Bryniarski, Andrzej Paradysz, Konrad Jersak, Jerzy Niemirowicz, Piotr Słupski, Piotr Jarzemski, Michał Skrzypczyk, Jakub Dobruch, Michał Puszyński, Michał Soczawa, Mirosław Kordowski, Marcin Życzkowski, Andrzej Borówka, Joanna Bagińska, Kazimierz Krajka, Małgorzata Stawicka, Olga Haus, Hanna Janiszewska, Agnieszka Stembalska, and Maria Małgorzata Sąsiadek

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;136:359–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter BS, Beaty TH, Steinberg GD, Childs B, Walsh PC. Mendelian inheritance of familial prostate cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:3367–3371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mucci LA, Hjelmborg JB, Harris JR, Czene K, Havelick DJ, Scheike T, et al. Familial risk and heritability of cancer among twins in Nordic countries. JAMA. 2016;315:68–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher FR, Al Olama AA, Berndt SI, Benlloch S, Ahmed M, Saunders EJ, et al. Association analyses of more than 140,000 men identify 63 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:928–936. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0142-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewing CM, Ray AM, Lange EM, Zuhlke KA, Robbins CM, Tembe WD, et al. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:141–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, Baker SM, Berlin M, McAdams M, et al. The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1401–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705153362001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong X, Wang L, Taniguchi K, Wang X, Cunningham JM, McDonnell SK, et al. Mutations in CHEK2 associated with prostate cancer risk. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:270–280. doi: 10.1086/346094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cybulski C, Górski B, Debniak T, Gliniewicz B, Mierzejewski M, Masojć B, et al. NBS1 is a prostate cancer susceptibility gene. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1215–1219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Na R, Zheng SL, Han M, Yu H, Jiang D, Shah S, et al. Germline mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 distinguish risk for lethal and indolent prostate cancer and are associated with early age at death. Eur. Urol. 2017;71:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raymond VM, Mukherjee B, Wang F, Huang SC, Stoffel EM, Kastrinos F, et al. Elevated risk of prostate cancer among men with Lynch syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:1713–1718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Ma J, Wu J, Ye L, Cai H, Xia B, et al. PALB2 links BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the DNA-damage response. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:524–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid S, Schindler D, Hanenberg H, Barker K, Hanks S, Kalb R, et al. Biallelic mutations in PALB2 cause Fanconi anemia subtype FA-N and predispose to childhood cancer. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:162–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang X, Leslie G, Doroszuk A, Schneider S, Allen J, Decker B, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline PALB2 pathogenic variants: an International Study of 524 Families. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020;38:674–685. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cybulski C, Kluźniak W, Huzarski T, Wokołorczyk D, Kashyap A, Rusak B, et al. The spectrum of mutations predisposing to familial breast cancer in Poland. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;145:3311–3320. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cybulski C, Kluźniak W, Huzarski T, Wokołorczyk D, Kashyap A, Jakubowska A, et al. Clinical outcomes in women with breast cancer and a PALB2 mutation: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:638–644. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lener MR, Scott RJ, Kluźniak W, Baszuk P, Cybulski C, Wiechowska-Kozłowska A, et al. Do founder mutations characteristic of some cancer sites also predispose to pancreatic cancer? Int. J. Cancer. 2016;139:601–606. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Łukomska A, Menkiszak J, Gronwald J, Tomiczek-Szwiec J, Szwiec M, Jasiówka M, et al. Recurrent mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51C, PALB2 and CHEK2 in Polish patients with ovarian cancer. Cancers. 2021;13:849. doi: 10.3390/cancers13040849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page EC, Bancroft EK, Brook MN, Assel M, Battat MHA, Thomas S, et al. Interim results from the IMPACT study: evidence for prostate-specific antigen screening in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur. Urol. 2019;76:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandão, A., Paulo, P. & Teixeira, M. R. Hereditary predisposition to prostate cancer: from genetics to clinical implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 10.3390/ijms21145036 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Cybulski C, Carrot-Zhang J, Kluźniak W, Rivera B, Kashyap A, Wokołorczyk D, et al. Germline RECQL mutations are associated with breast cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:643–646. doi: 10.1038/ng.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cybulski C, Wokołorczyk D, Kluźniak W, Jakubowska A, Górski B, Gronwald J, et al. An inherited NBN mutation is associated with poor prognosis prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2013;108:461–468. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tischkowitz M, Sabbaghian N, Ray AM, Lange EM, Foulkes WD, Cooney KA. Analysis of the gene coding for the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2 in hereditary prostate cancer. Prostate. 2008;68:675–678. doi: 10.1002/pros.20729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pakkanen S, Wahlfors T, Siltanen S, Patrikoski M, Matikainen M, Tammela T, et al. PALB2 variants in hereditary and unselected Finnish Prostate cancer cases. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 2009;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matejcic M, Patel Y, Lilyquist J, Hu C, Lee KY, Gnanaolivu RD, et al. Pathogenic variants in cancer predisposition genes and prostate cancer risk in men of African ancestry. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2020;4:32–43. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leongamornlert DA, Saunders EJ, Wakerell S, Whitmore I, Dadaev T, Cieza-Borrella C, et al. Germline DNA repair gene mutations in young-onset prostate cancer cases in the UK: evidence for a more extensive genetic panel. Eur. Urol. 2019;76:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southey MC, Goldgar DE, Winqvist R, Pylkäs K, Couch F, Tischkowitz M, et al. PALB2, CHEK2 and ATM rare variants and cancer risk: data from COGS. J. Med. Genet. 2016;53:800–811. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Yu H, Li S, Wiley K, Zheng SL, LaDuca H, et al. Rare germline pathogenic mutations of DNA repair genes are most strongly associated with grade group 5 prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2020;3:224–230. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2019.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, De Sarkar N, Abida W, Beltran H, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, Dadaev T, Tymrakiewicz M, Goh C, Jugurnauth-Little S, et al. Frequent germline deleterious mutations in DNA repair genes in familial prostate cancer cases are associated with advanced disease. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;110:1663–1672. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darst BF, Dadaev T, Saunders E, Sheng X, Wan P, Pooler L, et al. Germline sequencing DNA repair genes in 5,545 men with aggressive and non-aggressive prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heikkinen T, Kärkkäinen H, Aaltonen K, Milne RL, Heikkilä P, Aittomäki K, et al. The breast cancer susceptibility mutation PALB2 1592delT is associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:3214–3222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng M, Chen HH, Zhu X, Luo M, Zhang K, Xu CJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of germline mutations in BRCA1/2 and PALB2 genes in 2769 unselected breast cancer patients in China. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;145:1517–1528. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Bono J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, Sandhu S, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2091–2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grellety T, Peyraud F, Sevenet N, Tredan O, Dohollou N, Barouk-Simonet E, et al. Dramatic response to PARP inhibition in a PALB2-mutated breast cancer: moving beyond BRCA. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:822–823. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The main research data supporting the results of this study are included in Tables 1–3 and Figs. 1 and 2. Other data can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.