Abstract

Objective

To determine if structured worksheets can aid resident teaching on the obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) clerkship.

Design

We developed structured worksheets to aid residents in teaching medical students. In this pilot study, we measured the impact of the material by conducting end of clerkship focus groups between October 2017 to June 2018 and administering surveys to medical students who had recently completed the clerkship. We performed analyses of the focus group transcriptions for positive and negative themes and analyzed questionnaire data utilizing unpaired t-test and chi-square test to determine whether resident use of structured worksheets influenced student perception of resident teaching quality.

Setting

Medical students rotated at either an academically affiliated public safety-net hospital or tertiary maternity care hospital.

Participants

Medical students completing the OB/GYN clerkship volunteered to participate.

Results

A total of 37 students participated in focus groups and completed the survey. Focus group comments revealed a generally positive attitude towards the structured worksheets. The survey data revealed that this material helped to facilitate student’s clinical reasoning skills and assisted residents in using questions to effectively teach.

Conclusions

Structured worksheets can aid resident teaching on the OB/GYN clerkship. Students perceived the teaching material most favorably when residents utilized the material in a purposeful and timely manner. Effective resident use of structured worksheets on the OB/GYN clerkship can strengthen a culture that promotes student learning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-021-01318-7.

Keywords: Medical education, Resident educator, Structured worksheets, OB/GYN, Focus group

Introduction

Medical students estimate that a third of their clinical learning comes from residents, and residents, in turn, view teaching as one of their important professional responsibilities [1, 2]. There has been concern that pre-clinical medical school curriculum does not adequately prepare students for the clinical learning environment, leading to a need for a quick “catch up” when beginning a core clerkship [3]. However, clinical workload can constrain resident teaching efforts, particularly in OB/GYN, where nationwide surveys have demonstrated residents rank among the least effective teachers out of all the core clerkships [4, 5].

Several residency programs have instituted resident-as-teacher programs designed to train, assess, and improve resident’s teaching of medical students [6]. One of the initiatives of the resident-as-teacher program within our institution was the creation of structured worksheets that addressed common topics in the field of OB/GYN that was made available to residents so they could work through the material with rotating students. Learner-centered strategies like structured worksheets have been commonly used in other educational arenas. One study evaluating their use in undergraduate biology courses found greater post-assessment scores in the groups exposed to more student-centered and active learning pedagogies [7].

Our aim was to evaluate the impact of the structured worksheets on resident teaching of medical students on the OB/GYN clerkship. OB/GYN residents and attendings created worksheets covering important clinical topics such as fetal heart rate tracings, abnormal uterine bleeding, and postpartum hemorrhage. The goal was to create a hybrid of didactics and problem-based learning that could be done in short sessions during a clinical rotation.

Materials and Methods

From January to May of 2017, we developed structured worksheets on basic OB/GYN topics that students would be expected to understand by the end of their clinical rotation. The structured worksheets were based on sentinel clinical literature that were felt to integral to medical student’s foundational knowledge of obstetrics and gynecology (Appendix) [8–16]. The worksheets were designed by individual residents and attendings with the goal of covering a core topic that students would encounter on the core clerkship. Designers were instructed to focus on the high-yield teaching points that would help students succeed clinically on the rotation and prepare them for the end-of-rotation exam. In general, the worksheets were a single page with fill-in-the-blank questions that students could then fill in during a guided session with resident educators and then be used as a study guide to prepare for the exam. We distributed these materials to all 48 OB/GYN residents on flash drives in June 2017. Structured worksheets were also stored in paper format in resident workrooms. All residents were informed about the availability of these materials, but it was not mandatory for residents to use them.

Beginning in October 2017, authors CCK and BMR facilitated end-of-clerkship focus groups with medical students (MS-2 s, MS-3 s, and MS-4 s) at the conclusion of their 8-week OB/GYN clerkship. At the outset of the clerkship, prior to any interactions with the residents or other faculty, student participants volunteered to participate in the focus groups. The students were excused from their clinical duties to participate in the study. We obtained verbal consent at the outset of each focus group and transcribed the content in a deidentified manner using a third-party transcription service.

The main purpose of the focus groups was to understand the medical student experience with resident teaching [17]. We performed a sub-analysis of this qualitative data to assess views of the structured worksheets. We extracted transcript comments regarding resident use of worksheets and analyzed them for positive, neutral, and negative themes.

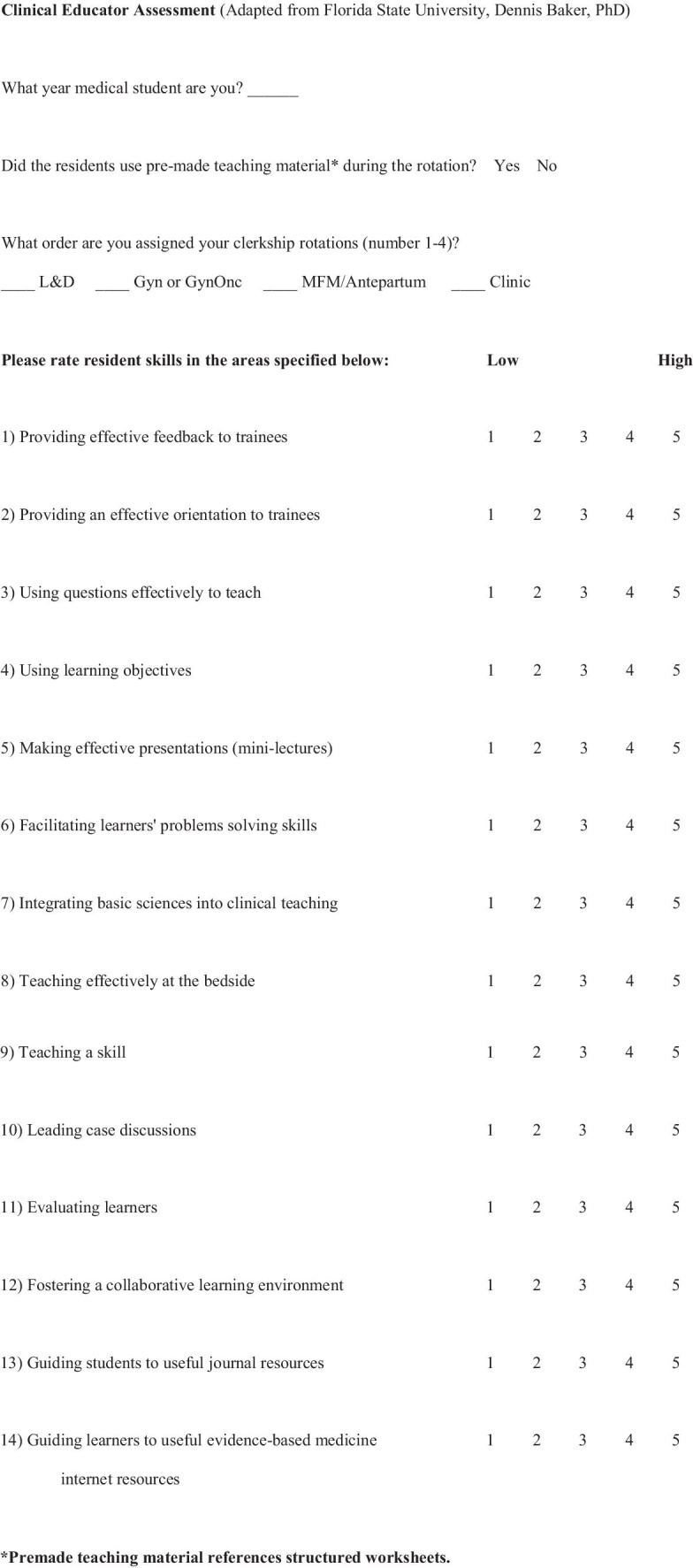

We also distributed an anonymous survey to the students at the beginning of each focus group. This fourteen-item survey was based on the Clinical Educator Self-Assessment, an unpublished instrument developed by Dennis Baker, PhD, at Florida State University (Fig. 1). This modified questionnaire asked students to rate resident teaching skills on a 1–5 (1 = low, 5 = high) Likert scale. This assessment has been used as an outcome measure for resident-as-teacher programs and has evidence of content validity [18, 19]. We included questions regarding resident use of the structured worksheets as well as demographic information. An unpaired t-test was used to compare mean student scores based on resident use of the structured worksheets. Chi-square test of proportions was used to compare answers to individual questions stratified by resident use of the structured worksheets by grouping answer choices into a binary comparison. All statistical analysis was performed using Prism 7, version 7.01, GraphPad, CA. This mixed method study was approved by Baylor College of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board.

Fig. 1.

Clinical Educator Assessment (

Adapted from Florida State University, Dennis Baker, PhD)

Results

We performed five focus groups with six to nine students each from October 2017 to June 2018. During this time period, 155 students completed the OB/GYN clerkship, and of those, a total of 37 students (24%) participated in focus groups and completed the survey. Eighteen (48%) were 2nd-year students, eleven (30%) were 3rd-year students, and eight (22%) were 4th-year students. All 37 students also filled out the survey.

Twelve students (32%) responded to the survey stating that residents used the structured worksheets, while twenty-five students (68%) stated that residents did not. There was a trend among students who worked with residents that used the structured worksheets to rate resident teaching skills on average higher than those students who did not have residents use structured worksheets (3.39 vs 2.90, p = 0.09).

The distribution of answers to the clinical educator assessment stratified by use of structured worksheets is reported in Table 1. For the purposes of statistical comparison, those medical students answering a question at a 1, 2, or 3 and those medical students answering a question at a 4 or 5 were grouped together (1 = low; 5 = high). Mean scores for answers to individual questions are also presented but were not used for statistical comparison. Residents that used the structured worksheets were significantly more likely to be rated a 4 or 5 in three of the fourteen areas: providing an effective orientation to trainees (p = 0.01), facilitating students’ clinical reasoning skills (p = 0.01), and using questions effectively to teach (p = 0.02). There was no significant difference in the answers in the other eleven areas.

Table 1.

Comparison of medical student responses to Baker Clinical Educator Self-Assessment Survey based on use of structured worksheets

| Prompt | Structured worksheets | Worksheets not used | p-Value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–3 | 4–5 | Mean | 1–3 | 4–5 | Mean | ||

| Providing effective feedback to trainees | 7 | 5 | 3.50 | 18 | 7 | 2.88 | 0.45 |

| Providing an effective orientation to trainees | 7 | 5 | 3.08 | 23 | 2 | 2.60 | 0.01** |

| Using questions effectively to teach | 2 | 10 | 4.00 | 14 | 11 | 3.44 | 0.02** |

| Using student learning objectives | 12 | 0 | 2.58 | 23 | 2 | 2.24 | 0.31 |

| Making effective mini-lectures | 6 | 6 | 3.08 | 17 | 8 | 2.76 | 0.29 |

| Facilitating students’ clinical reasoning skills | 4 | 8 | 3.83 | 19 | 6 | 3.00 | 0.01** |

| Integrating basic sciences into clinical teaching | 9 | 3 | 2.97 | 22 | 3 | 2.44 | 0.32 |

| Teaching effectively at the bedside | 4 | 8 | 3.75 | 14 | 11 | 3.32 | 0.30 |

| Teaching a skill | 2 | 10 | 4.17 | 7 | 18 | 3.84 | 0.45 |

| Leading a clinical case discussions | 8 | 4 | 2.92 | 21 | 4 | 2.56 | 0.23 |

| Evaluating students | 8 | 4 | 3.17 | 21 | 4 | 2.80 | 0.23 |

| Fostering a collaborative learning environment | 5 | 7 | 3.83 | 10 | 15 | 3.52 | 0.92 |

| Guiding students to useful journal resources | 8 | 4 | 3.08 | 20 | 5 | 2.40 | 0.37 |

| Guiding students to useful EBM internet resources | 5 | 7 | 3.50 | 17 | 8 | 2.80 | 0.13 |

Distribution of answers into negative (1–3) and positive (4–5) stratified by use of structured worksheets and mean of score in each group

*Chi-square test comparing students that answered 1–3 versus 4–5 stratified by resident use of pre-made teaching material

**Denotes statistical significance

Table 2 displays comments from focus group manuscripts that specifically described resident use of worksheets. Most comments were positive, displaying appreciation for resident preparedness to teach and knowledge gained from the worksheets. Neutral comments were regarding worksheet use and need to establish baseline knowledge level prior to use. Some negative comments described the worksheets as “busy work” and that their use revealed resident disinterest in teaching.

Table 2.

Qualitative comments regarding obstetric worksheets from medical student focus groups on resident teaching

| Comments | |

| Positive | “For L&D nights, I think it was the single most effective thing they did is they had a teaching worksheet. They had a little one page Microsoft Word workshop that was made by a second-year resident.” |

| “My partner and I found it to be really helpful when we were doing the criteria for what's labor and then fetal heart tones as well. Especially since it was our first week on L&D. They were really short, one page, we just worked on them on our own. She was like, ‘If you want to discuss any of it, if you have any questions, always feel free to ask.’” | |

| “And she had specific resources to pass out and to give. I was really impressed. Those worksheets were pretty awesome.” | |

| “On L&D, we got a worksheet on drugs, like the side effects. That was actually pretty useful, to look up all those drugs and look up their side effects, contraindications, all of that stuff. It reminded me of doing homework in high school; it was a good learning experience.” | |

| “When she first handed it to us, I was like, “You want us to do what?” But then as we worked on it, I was like, oh this is actually really good, I'm learning a lot of things.” | |

| Neutral | “If you could come up with the ones that are sort of most relevant, such as fetal heart tracings, and maybe try to get the residents to teach us on day 1 or day 2, as opposed to waiting until the last day.” |

| “Speaking a little bit to her point, so she had someone that gave her a work sheet. My thought was that sometimes, whenever residents ask you, “Do you have any questions?” Sometimes we don't necessarily know what we don't know, so it is good to have a common ground or a baseline of, “This is the sort of stuff that you should know,” like the worksheet, which was kind of basic information that you really do need to have solidified prior to having larger thoughts.” | |

| Negative | “It’s basically busy work for when L&D is not super busy and they’re like, let’s do this worksheet, and you're like, I’m actually doing my UWise questions. Or studying things.” |

| “I felt like they were just a way to occupy me so the resident didn't have to interact with me and then she didn't have to actually teach it. She could just read the answers off.” |

Conclusions

Our pilot study evaluated the effectiveness of structured worksheets on medical student education in the clinical learning environment. This project aimed to develop our residents as medical educators and facilitate their teaching of students. The primary roles of medical residents, providing patient care and educating learners, are often in conflict [20]. Morrison et al. demonstrated that residents typically enjoy teaching when time allows and that students prefer brief, but high-value learning over longer lectures [21]. We designed the teaching material with the goal of creating accessible teaching content that did not require significant preparation from residents.

Residents that used the structured worksheets were rated statistically that are more likely to provide effective orientation, facilitate clinical reasoning, and use questions effectively to teach. In our sample, it did not reach statistical significance, but overall, students also rated the resident teachers that utilized the worksheets as more effective teachers on average. The materials conveyed that there was an effort to provide formal medical student teaching, like how an effective orientation conveys willingness to teach. As a basis for discussion, the worksheets gave the residents a guide to explain concepts which facilitated a safe space to ask clinical questions. By focusing on basic concepts, the residents have straightforward pathways to orienting the students to the clinical workflow and expectations. The teaching tools were focused on straightforward clinical scenarios, facilitating clinical questions that avoided “on the fly” and “pimping” questions which can often facilitate a hostile environment [22]. To aid those students that struggle with the transition to the clinical environment, the style and structure were similar to pre-clinical didactics [23]. This similarity creates a platform for students as they begin to demonstrate clinical reasoning, strengthening skill transition. Previous work has shown that students appreciate a clerkship handbook to aid in the transition to a new clinical rotation, and these worksheets may serve in a similar fashion to guide students to foundational clinical knowledge [24].

Overall, our focus groups revealed a generally positive impression of using structured worksheets to facilitate learning, with students expressing appreciation for resident teaching. Students also expressed that timing the use of the structured worksheets at the beginning of the rotation can help build a better clinical knowledge base for more complex topics. Not all students found the material to be helpful teaching tools. We suspect this was related to variation in resident use of the materials. Some students felt that residents used the material as standalone teaching, rather than a basis for guided discussion. This finding supports the idea that effective teaching requires the resident to make time and display an interest in teaching. Past studies have shown that positive attitudes towards teaching can both improve perceived effectiveness of the teacher and influence learners on their specialty choices [25, 26].

Our study is limited by the short time period and its single institution setting, and we did not evaluate the worksheets themselves, but merely whether they were utilized. Almost half of the students on the rotation were second-year students due to a condensed 18-month pre-clinical course work at our institution. These students have limited experience on clinical rotations and may require different approaches to teaching compared to more experienced students. We may have also excluded some student’s interaction with residents due to recall bias with the focus groups at the end of the rotation. In addition, we did not survey resident use and attitudes toward the material, which would allow us to edit our intervention to build engagement from the residents. Using a Likert scale to assess views has natural limitations, including the limited number of discrete choices to represent a continuous variable. Therefore, the attitudes in between numbers on the scale are pushed one way or another, and there is a tendency to avoid extreme values, which pushes responses to the middle [27].

To improve resident teaching at our institution, we plan to use end-of-rotation comments to continue to address and guide future resident teaching efforts. Also, we will continue to improve the current worksheets and develop new materials targeting topics important to students. Encouraging residents to use the most high-yield material at the beginning of sub-rotations remains another opportunity to optimize their impact. Based on our study, structured worksheets can enhance the perception of effective resident teaching of students. The material especially strengthened favorable student perception among committed, sincere resident teachers. The pre-made nature of the material shifts teaching tool creation off residents and can reinforce important concepts for students, especially when used early in the rotation. In the future, development of assessment methods for the material will allow us to evaluate their success in conveying key clinical knowledge to students.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeff Lin, MD for his creation of the Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia Worksheet and Dennis Baker, PhD, of Florida State University for the use of the unpublished Baker Clinical Educator Self-Assessment.

Author Contribution

All authors made substantial contribution of concept and/or design of this manuscript, drafted and/or revised the manuscript, agreed to be accountable for the work, and have approved the final version for submission.

Data Availability

Data available at request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Approved by Baylor College of Medicine IRB.

Consent to Participate

All study participants consented to be part of the group and be included in research.

Consent for Publication

All authors consent to submitting this final version for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Busari JO, Prince KJAHAH, Scherpbier AJJAJA, et al. How residents perceive their teaching role in the clinical setting: A qualitative study. Med Teach. 2002;24(1):57–61. 10.1080/00034980120103496. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Barrow MV. Medical student opinions of the house officer as a medical educator. J Med Educ. 1966;41(8):807–810. doi: 10.1097/00001888-196608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Windish DM, Paulman PM, Goroll AH, Bass EB. Do clerkship directors think medical students are prepared for the clerkship years? Acad Med. 2004;79(1):56–61. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy ST, Zegarek MH, Fromme HB, Ryan MS, Schumann S-A, Harris IB. Barriers and facilitators to effective feedback: a qualitative analysis of data from multispecialty resident focus groups. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):214–219. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00461.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges. Graduation Questionnaire (GQ) - Data and Analysis - AAMC, aamc.org. Accessed Sept 22, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data/gq.

- 6.Ricciotti HA, Dodge LE, Head J, Atkins KM, Hacker MR. A novel resident-as-teacher training program to improve and evaluate obstetrics and gynecology resident teaching skills. Med Teach. 2012;34(1):e52–e57. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.638012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connell GL, Donovan DA, Chambers TG. Increasing the use of student-centered pedagogies from moderate to high improves student learning and attitudes about biology. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(1):ar3. 10.1187/cbe.15-03-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Practice Bulletin No. 128. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Diagnosis and management of benign breast disorders. Practice Bulletin No. 164.Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:e141–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Endometrial cancer. Practice Bulletin No. 149. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:1006–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Screening for fetal aneuploidy. Practice Bulletin No. 163. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:e123–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of intrapartum fetal heart rate tracings. Practice Bulletin No. 116. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1232–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 96. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:201–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist. Diagnosis and treatment of gestational trophoblastic disease. Practice Bulletin No. 53. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Postpartum hemorrhage. Practice Bulletin No. 183. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e168–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Belfort, MA. Overview of postpartum hemorrhage. Lockwood, CJ, Barss VA, ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc. https://www.uptodate.com. (Accessed on June 3rd, 2019)

- 17.Ratan BM, Greely JT, Jensen MD, Kilpatrick CC. A conceptual model for residents as teachers in obstetrics and gynecology. Medical Science Educator. 2020;30(3):1169–1176. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-00985-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaba ND, Blatt B, Macri CJ, Greenberg L. Improving teaching skills in obstetrics and gynecology residents: evaluation of a residents-as-teachers program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(1):87.e1-e87.e7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Berger JS, Daneshpayeh N, Sherman M, et al. Anesthesiology residents-as-teachers program: a pilot study. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):525–528. doi: 10.4300/jgme-d-11-00300.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yedidia MJ, Schwartz MD, Hirschkorn C, Lipkin M., Jr Learners as teachers: the conflicting roles of medical residents. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(11):615–623. doi: 10.1007/BF02602745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison EH, Hollingshead J, Hubbell FA, Hitchcock MA, Rucker L, Prislin MD. Reach out and teach someone: generalist residents’ needs for teaching skills development. Fam Med. 2002;34(6):445–450. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12164622 [PubMed]

- 22.Stoddard HA, O’Dell DV. Would Socrates have actually used the “Socratic method” for clinical teaching? J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1092–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3722-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho KK, Marjadi B, Langendyk V, Hu W. Medical student changes in self-regulated learning during the transition to the clinical environment. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0902-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atherley A, Taylor C., Jr Student perceptions of clerkship handbooks. Clin Teach. 2017;14(4):242–246. doi: 10.1111/tct.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berman AC. Good teaching is good teaching: a narrative review for effective medical educators. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;8(4):386–394. doi: 10.1002/ase.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elzubeir MA, Rizk DE. Identifying characteristics that students, interns and residents look for in their role models. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):272–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guilford JP. Psychometric Methods. McGraw-Hill; 1954.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available at request.