Abstract

Objectives

Medical students’ experiences of harassment and its influence on quality of life were examined.

Design

A set of databases were employed in this review, and using ATLAS.ti, a set of emergent themes were identified.

Results

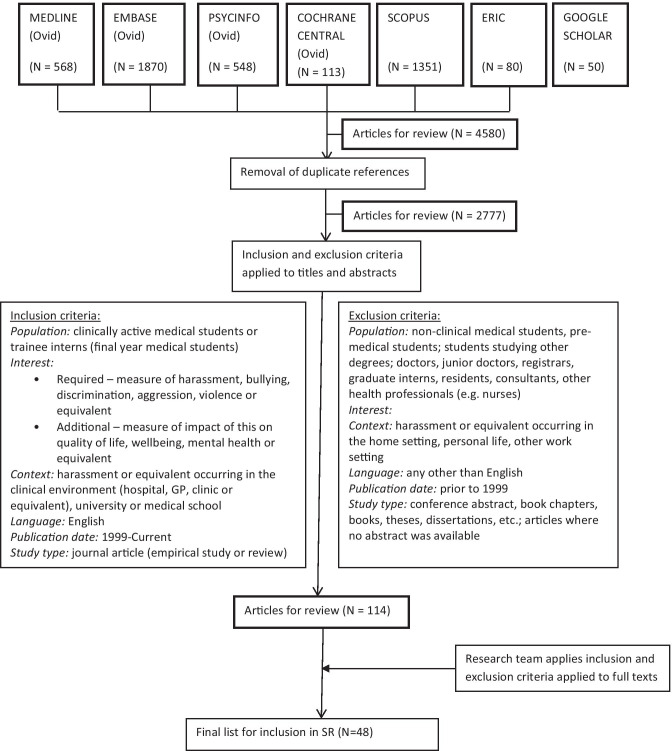

The initial search identified 4580 potential articles for review. The inclusion and exclusion criteria reduced the list to 48 articles. Two predominant emergent themes were categorised as ‘Antecedents’ of ‘harassment’ and ‘Consequences’ on quality of life.

Conclusions

Harassment likely has an adverse impact on quality of life, although more empirical research is required to establish more definitive links between the two variables.

Introduction

Medical students’ experiences of harassment and bullying have recently become essential topics for research [1, 2]. The media has commonly highlighted the disturbing extent of harassment and bullying which occurs during medical education and its impact on students and their ability to carry out their clinical work [3–6]. Furthermore, medical students’ quality of life has been raised as an issue of concern by all stakeholders within the medical education context, including students, lecturers and student support personnel [7–9]. In this study, we were interested in exploring the evidence regarding the impact that harassment or bullying may have on students’ quality of life. It makes intuitive sense to suggest that harassment/bullying adversely affects quality of life; however, the claims underpinning this assumption and the complexity of the issues between them require meticulous investigation.

Harassment and bullying do not occur in isolation and wider systemic and social issues must be considered. Simpson and Cohen [10] state that “Both harassment and bullying concern unwanted behaviour which causes offence to the targeted individual and which is not justified by the working or professional relationship.” They propose that harassment, however, is linked with adverse behaviour towards someone based on race, sex, disability, age or sexual orientation. In contrast, they view bullying as working at a more individual level “based on personality traits, work position or levels of competence”. Nonetheless, Skinner and colleagues [11] suggest that both harassment and bullying involve the abuse of power, and although we recognise the terms could be semantically differentiated, we agree with Skinner and colleagues and will not aim to differentiate between the two terms in reference to their impact or prevalence. We also note that other terms are commonly used to frame harassment and bullying, such as abuse, discrimination, mistreatment and so forth [12–15]. Henceforth, we will use the term harassment with the acknowledgement that this term can be used interchangeably with other aforementioned terms.

The notion of quality of life is also multi-layered and complex. It can be conceptualised as either a unidimensional or multidimensional construct [16]. Quality of life can refer to physical health, psychological health, social relationships and the impact of the environment [17]. Measures of quality of life can be determined through subjective evaluations (e.g. feelings of satisfaction or contentment) or by appraising objective measures (e.g. financial resources). There are numerous articles [14, 18] documenting the plight of medical students and concerns related to reduced quality of life [19, 20]. For example, Dyrbye and colleagues [8] report that distress is commonplace amongst medical students, anxiety, depression, cynicism, loss of compassion, burnout, substance abuse and suicidal ideation. In more recent studies [21–23], similar results indicate that these sequelae have not abated and concerns related to mental and physical health are frequently cited across the globe [24].

A preliminary literature search revealed that claims have been made regarding the deleterious effect harassment appears have on medical students’ quality of life [25], and in particular when they are being trained within the clinical context [2, 26, 27]. Therefore, we decided to conduct a rigorous search of the literature to evaluate the evidence of such claims. The research questions guiding this study were “What are medical students’ experiences of harassment in the clinical workplace in relation to their quality of life, and does harassment adversely affect quality of life?” We contend that this review will assist in either confirming the claim that harassment adversely affects medical students’ quality of life, or if this is not evident, then this search will assist in developing more focussed future research in this area.

Materials and Methods

The Search Process

We decided to apply a scoping review process because our aim was to explore a broad research question aimed at identifying themes, quality of evidence and potential gaps in the research [28]. We developed this approach by conducting a systematic search, selecting appropriate literature published in refereed journals and synthesizing this information into meaningful themes [28]. Our review was based on a PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) Framework [29] using the following criteria:

Types of participants: Medical students (note: some medical programs refer to final year students as interns and these students have been included).

Types of intervention: Experience of harassment, discrimination, bullying in the clinical workplace.

Types of comparison: Those who have experienced (versus those who do not) harassment, discrimination, bullying in the clinical workplace.

Types of outcome measures: Those pertaining to quality of life and other variants (see Table 1). Table 1 shows the variants for the keywords and phrases associated with harassment, quality of life and medical students. In addition, inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in more detail in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Medical subject headings (MeSH) used in search of Medline database

| MeSH | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Harassment | |

|

•Harassment, Non-Sexual •Sexual Harassment •exp Bullying o(includes cyberbullying) •exp Social Discrimination o(includes ageism, homophobia, racism, sexism, xenophobia) •Violence |

•Harass* •Bully* •Bullied •Cyberbull* •Discriminat* •Abus* •Mistreat* •Hostil* •Aggressi* •Violen* |

| Quality of life | |

|

•Quality of Life •Happiness •Mental health |

•Quality of life •Well being •Happiness •Mental health •Depress* •Anxiety |

| Medical students | |

|

•Students, Medical •Education, Medical, Undergraduate •Schools, Medical |

•Medic* ADJ2 student* •Medic* ADJ2 school* •Medic* ADJ2 education |

The asterisk (*) serves as the truncation operator. The search words match if they start with the specified word prefix stated before the asterisk (*) operator

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram used in search strategy

Scoping searches were conducted during November and December, 2019. The databases utilised were Medline (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), PsycINFO (Ovid), Cochrane Central (Ovid), Scopus, ERIC and Google Scholar (first five pages only).

Data Analysis

The decisions for choosing the articles for final review were guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In addition, only refereed journal articles were considered for review. The decision-making process of the articles for each stage of the review was documented using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, and this selection process is presented as a flow diagram (Fig. 1) [30].

A final summary (Table 2) was developed through adapting key review elements employed in other scoping reviews [31–33]. The key tabulated categories used in this review (see Table 2) and relevant to this field of study were (1) first study author and year, (2) country where the study originated, (3) study design and (4) key claims and findings: harassment links with the quality of life. Table 2 enables us to conduct the final synthesis of the key outcomes as directed by the Cochrane consumers and communication guidelines [34]. The salient themes and patterns emerging from the key findings of the final reviewed articles were analysed using a data synthesis approach [34] and with the assistance of the ATLAS.ti qualitative software programme [35] culminating in the identification of key themes.

Table 2.

Summary of articles reviewed

| First author (year) | Country | Study design | Key claims and findings: harassment links with quality of life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pottier (2015) | France | Prospective randomised crossover study | Medical students were subjected to external stressors (e.g. the patient demonstrated lack of confidence in the student’s competency and demonstrated moderately aggressive behaviour), which resulted in increased scores on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| Berryman (2018) | New Zealand | Mixed Methods | Five incidents of bullying or harassment were reported leading to adverse wellbeing (e.g. increased stress and worry) and learning deficiencies |

| Esan (2019) | Nigeria | Systematic review | High levels of psychological distress were identified and linked with mistreatment by colleagues and trainers |

| McKenna (2017) | Australia | Scoping Review | Abuse noted amongst international health students, e.g. racial and verbal abuse leading to the feeling of being frightened |

| Haglund (2009) | USA | Longitudinal survey | Non-traumatic stressful events (e.g. mistreatment by superiors and poor role modelling) were linked to repeated memories of these events, feeling very upset when reminded of these events, and avoiding thoughts or activities related to these events |

| Hardeman (2016) | USA | Longitudinal survey | Negative racial climate was linked to depressive symptoms. An inequitable medical school environment is harmful for all students with strongest effects among Asian students |

| Przedworski (2015) | USA | Cross-sectional stratified survey | Homosexual and bisexual students were more likely to report being harassed than heterosexual students leading to greater isolation, anxiety, self-rated health, and depression |

| Fond (2018)[40] | France | Cross-sectional survey | Domestic violence and sexual assault experienced by women and physical assault for men. Women reported to be more frequently counselled and antidepressants and anxiolytics use with impaired QoL. Men reported drug/alcohol addiction |

| Fond (2018)[41] | France | Cross-sectional survey | Psychiatry interns were found to have increased rates drug/alcohol use disorder, increased antidepressant and anxiolytic consumption, increased need for counselling and reduced self-reported vitality. They reported sexual and physical assault during their medical studies |

| Dyrbye (2007) | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Racial discrimination (bigotry, harassment, and unfair performance evaluations) adversely impacts students’ quality of life (e.g. higher depression and burnout scores amongst minority groups) |

| Elnicki (2002) | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Women more likely to feel abused than men. Personal consequences include depression, anger, humiliation, aggression, and suicidal thoughts. Adverse effect noted on learning e.g. avoid certain clinical rotations |

| Frank (2006) | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Harassment and belittlement related to suicidal ideation, increased drug/alcohol use, and lowered career confidence |

| Kapoor (2016) | India | Cross-sectional survey | Consumption of alcohol and cigarettes was found to be significantly associated with physical bullying |

| Kolkijkovin (2019) | Thailand | Cross-sectional survey | Psychological abuse is an associated factor when explaining the incidence of depression |

| Maida (2003) | Chile | Cross-sectional survey | Deleterious effects of abuse include: issues with physical health, mental health, social life, family life, quality of work, image of physicians, considered leaving medical school, motivation to study, afraid of reprisals, and self-worth |

| McEvoy (2019) | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Effect of pimping (attending poses a series of very difficult questions to an intern or student) on QoL is equivocal? “Whether pimping truly represents learner mistreatment is unclear, and there remains a case in favour of the practice depending on how one defines it.” |

| Oku (2015) | Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey | Mistreatment occurred in 36% of the sample, although of the link between those who experienced mistreatment and poor mental health was not evident |

| Owoaje (2012) | Nigeria | Cross-sectional survey | 98.5% of respondents experienced one or more forms of mistreatment during their training (e.g. being shouted at (92.6%), being publicly humiliated or belittled (87.4%)). Effects of the mistreatment include: stress (64.0%), strained relationships between the affected student and the perpetrator of the abuse (63.4%), loss of confidence (45.4%), depression (40.5%), lowered academic performance (24.4%) and sleeping problems (22.1%) |

| Paice (2004) | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional survey | Most of the negative behaviours (bullying) were perpetrated by other doctors, in a pecking order of seniority. Some of the behaviours that erode trainees’ professional confidence or self-esteem may be attempts by trainers to improve their performance |

| Perry (2016) | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Racial harassment was linked to depression, anxiety, perceived stress, and fatigue increased and state self-esteem decreased |

| Qamar (2015) | Pakistan | Cross-sectional survey | New medical students face bullying leading to lowered self-esteem and changes in personality. More female (90%) than male medical students reported having been victims of bullying (e.g. verbal, emotional, or institutional) |

| Rademakers (2008) | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional survey | Sexual harassment from patients almost exclusively concerned female students. Most of the incidents were either flirtatious or sexual remarks. Consequences include some students felt uncertain and inhibited when making contact with patients after an incident |

| Romo-Nava (2019) | Mexico | Cross-sectional survey | All types of current abuse (outside and inside the academic environment) were associated to an increased risk of scoring positive for a current Major Depressive Disorder |

| Shoukat (2010) | Pakistan | Cross-sectional survey | Mistreatment was reported (62.5%) by medical students. 69.7% were males and 54.9% were females. A relationship between gender, year division, stress and possible use of drugs/alcohol and reported mistreatment but no relationship with psychiatric morbidity |

| Vargas (2020) | USA | Cross-sectional survey | Women (82.5%) and men (65.1%) indicated experiencing at least one incident of sexual harassment from institutional insiders (e.g. staff, students, and faculty), which was independently associated with lower mental health, job satisfaction, and sense of safety |

| Xie (2017) | China | Cross-sectional survey | 30.6% reported patient-initiated aggression at least once (e.g. mental abuse (20.4%), offensive threats (14.6%), physical violence (8.3%), and sexual harassment (verbal: 8.3% or physical: 1.6%). However, patient-initiated aggression did not affect the medical students’ quality of life |

| Daud (2016) | Pakistan | Qualitative focus groups | Participants expressed concerns about harassment leading to demoralization and ‘nerve wrecking’ |

| Toman (2019) | USA | Qualitative focus groups | LGBTQ medical students recognised that the fear of discrimination deterred them from creating close relationships with their advisers, making them feel isolated |

| Doulougeri (2016) | Greece | Qualitative interviews | Instances of being humiliated in front of patients leading to feelings of powerlessness and, discomfort, shame and embarrassment |

| Monrouxe (2012) | England, Wales and Australia | Qualitative interviews | Examples of verbal humiliation and physical mistreatment leading to adverse emotional consequences, such as feeling upset, horrible and scared |

| Rees | England, Wales and Australia | Qualitative interviews | Types of abuse included verbal, sexual harassment, witnessing abuse of others, and physical abuse. Factors contributing to abuse include perpetrator, work and perpetrator-recipient relationship. Consequences included feeling fearful and worried about impact on learning |

| Aysola (2018) | USA | Narrative analysis | Lack of inclusion leads to psychological distress and workforce maladaptation requiring systems level interventions |

| Botha (2017) | Canada | Opinion | Harassment, bullying, and intimidation are unexplored but may have long-term negative effects on wellbeing and mental health. Victims of abuse (medical students and physicians) may experience indifference and shaming |

| Coopes (2016) | Australia | Opinion | Case examples of bullying, discrimination and sexual harassment found in the medical profession (e.g. Surgery) created a culture of fear and other mental health issues (e.g. suicidal thoughts) |

| Dyrbye (2005) | USA | Opinion | Depression, burnout, stress and other psychological distress symptoms are common amongst students and frequently mentioned antecedents include the direct experience of abuse and/or witnessing abuse |

| Dzau (2018) | USA | Opinion | Sexual harassment is frequently voiced amongst female students (e.g. 40 to 50% in some instances). This includes gender-based harassment, unwanted sexual attention and sexual coercion. Consequences are increased levels of depression, anxiety, stress and so forth |

| Elnicki (2010) | USA | Opinion | Mistreatment of medical students has a profoundly negative consequences including depression, substance abuse, changing career direction, and leaving medicine entirely |

| Ferguson (2015) | New Zealand | Opinion | Bullying seen as a rite of passage in surgery. Bullying in the clinical environment leads to poor performance, anxiety and absenteeism |

| George (2015) | USA | Opinion | Comics by students depicted physicians as monsters and themselves as victims of mistreatment. Individuals subjected to such mistreatment are at risk of psychological distress and decreased workplace performance |

| Grissinger (2015) | USA | Opinion | Repetitive demeaning treatment of nurses, medical students, and residents has resulted in numerous cases of “burnout” and clinical depression |

| Kalaichandran (2019) | USA | Opinion | Potential links between learning environment culture, prevalence of bullying and harassment and depression, anxiety, burnout and suicidal ideation |

| Parikh (2017) | USA | Opinion | Long-term bullying leads to mental and physical issues for victims (e.g. anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, sleep disorders, weight loss, increased risk of cardiovascular disease and musculoskeletal pain, and absenteeism |

| Roberts (2009) | USA | Opinion | Bullying and abuse of trainees in USA—mistreatment (17%); unwanted sexual advances (5%); hit, slapped, or pushed (2%); exchanged sexual favours for grades or other rewards (1%). Reduced opportunities due to gender, race or ethnicity, and sexual orientation |

| Schernhammer (2005) | USA | Opinion | Implied link between suicide and forms of harassment, e.g. sexual harassment incurred by women |

| Singh (2018) | USA | Opinion | Bullying can lead to depression, helplessness, anxiety and despair, suicide ideation, psychosomatic and musculoskeletal complaints, and the risk of cardiovascular disease. And increased drug/alcohol usage and decreased satisfaction |

| Stone (2015) | USA | Opinion | Literature suggests 59.4% of medical trainees experienced harassment or discrimination (sexual harassment at 33%) and Consultants were the most likely offender. This had negative impacts on emotional and physical wellbeing and professional behaviour |

| Ward (2014) | Australia | Opinion | Recent media attention on workplace bullying and the 2013 beyond blue report describing poorer than expected mental health of medical students. Hidden and undiscussed toxic culture persists contributing to burnout and mental ill-health |

| Wood (2006) | United Kingdom | Opinion | Clinical practice exposes medical students to bullying and harassment (more commonly reported by female students). 85% of students reported having been harassed or belittled and 40% had experienced both. Links to higher rates of alcohol misuse, depression, and suicidal intent and with lower satisfaction with their chosen career as a doctor |

Results

Summary of the Search Strategy

The number of initial hits (n = 4580) generated from the selected databases is shown in Fig. 1, indicating that the Scopus and Embase were the most fruitful source of information. After removing duplicates, this initial capture was reduced to 2777 articles and these were examined in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria (as described in Fig. 1) and discussed between two authors. The full article examination was conducted by one of the researchers resulting in a list of 114 potential articles. After which, this list was audited by three other authors and the final list was reduced to 48 articles.

Research Design and Origin of Articles

Based on the PRISMA search protocol [28], we were able to determine the types of research designs associated with the final review articles. As shown and described in Table 2, the reviewed articles were sorted according to the types of research design incorporated. We used an established evidence-quality classification system [36] and category consensus for each paper reviewed was reached following discussion between four investigators. We noted that only one study [37] used a high-level research design, namely a prospective randomised crossover study and one study used a mixed methods approach [38]. Two review studies have been conducted, one a systematic review [20] and the other a scoping review [13]. The most common study design used in included reports was a survey, and more specifically, 20 articles used a cross-sectional survey design [14, 25, 27, 39–54] and two studies used a longitudinal survey approach [12, 55]. Qualitative studies were less commonly undertaken, and in this review, we identified six qualitative studies using either individual interviews or focus groups [15, 56–60]. We also identified 16 opinion articles, deemed to be the lowest level of evidence [1, 8, 26, 61–73].

The study samples were identified and used as a proxy for regional derivation for researchable articles. Regional affiliation for opinion articles was derived from the first author affiliation. The majority of the articles (n = 22, 46%) utilised samples from the USA [8, 12, 14, 15, 39, 42, 46, 49, 53, 55, 60, 63–72, 74]. Four articles used samples from the UK [1, 48, 58, 59]. Although two of these articles used cross-sectional samples from England, Wales and Australia [58, 59], five articles incorporated Australian samples [13, 58, 59, 62, 73]. Three articles were derived from France [37, 40, 41], Pakistan [50, 52, 56], and Nigeria [20, 25, 47]. Two articles were identified from Canada [37, 61], and two from New Zealand [26, 38]. Finally, single articles were generated from the following regions: China [54], Greece [57], India [43], Mexico [51], Thailand [44], Chile [45] and The Netherlands [27].

Overall Summary of the Reviewed Articles

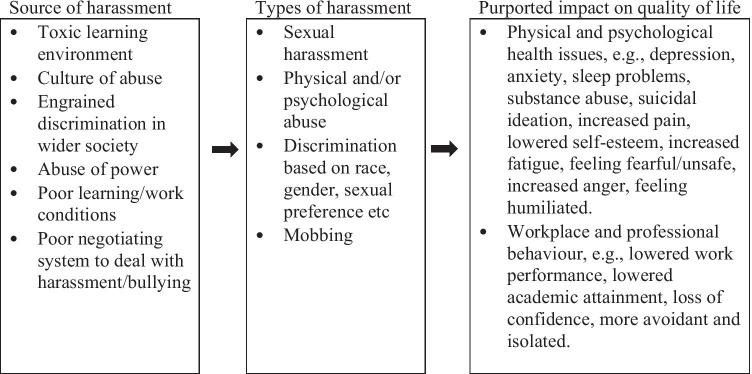

The key features of the articles included in the review are presented in Table 2. Employing ATLAS.ti [35] and a data synthesis approach [34], the key claims and findings (Table 2) linking harassment (or a similar synonym) with quality of life (or similar) were analysed for similarities and differences. This analysis resulted in a set of clearly defined themes that can be framed as antecedents and consequences.

Antecedents

(a) Workplace and learning environment

(b) Types of harassment

-

2.

Consequences

(a) Workplace and professional behaviour

(b) Psychological outcomes

(c) Physical wellness issues

Antecedents

Workplace and learning environment factors

Several workplace factors were identified explaining why harassment can proliferate in the clinical learning environment. For example, in their narrative analysis, Aysola and colleagues [60] noted that leadership in the workplace systematically marginalised certain minority groups making it “much harder to prove themselves and be treated with respect”. In addition, maternity leave and requests for religious leave were often not well received. Aysola and colleagues, further, illustrated issues associated with the cultivation of toxic work cultures, such as a culture of intimidation and the notion of being expendable, this in turn enforced social isolation, and a lack of engagement by the recipient. George and Green [65] examined students’ visual representations of the clinical learning environment and found that students would often imagine the environment as a dungeon with supervisors as ‘fiendish, foulmouthed monsters’ which accentuated the feeling of authority being maladaptive and creating toxic working and learning environments. Moreover, harassment towards students stems from various sources, including teachers, peers and patients [25, 54].

Types of harassment

Numerous incidents were identified related to harassment. Some of the extreme versions of harassment cited were in the form of sexual and physical abuse [25, 41, 54, 75]. Verbal humiliation was also cited in the literature [54, 58]. On the extreme physical end of the harassment scale, there is evidence that women are more at risk of being exposed to sexual assault, while men are more at risk of experiencing physical assault [40]. In addition, the subtypes of sexual harassment commonly experienced by women are gender-based harassment, unwanted sexual attention and sexual coercion [63]. Some students experienced incidents, which they labelled as traumatic, including threats of injury or death, or threats to integrity (i.e. attempts to discredit them as incompetent) [12]. Roberts [69] asserted that reduced opportunities are experienced due to gender, race or ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Consequences

Workplace, learning, and professional behaviour

The fear-induced consequences stemming from harassment can lead to avoidance of help-seeking, withholding ideas, increased turnover, fear of reprisals [45], blaming behaviours and maladaptive teams [26]. Harassment can also lead to absenteeism [26, 64], change in career choice [64], decreased satisfaction and sense of safety [53], decreased workplace performance [65], strained relationships between those involved and regret of career choice [1]. In addition, harassment has led to lowered academic performance [25], learning problems [38], decreased motivation to learn [45] and worries about impact on learning [59]. Sequalae of being on the receiving end of harassment often include victims becoming avoidant, silent and exhibiting unprofessional behaviour themselves (e.g. engaging in aggressive behaviour and avoiding clinical rotations) [37, 39, 72].

Psychological outcomes

Mental health and psychological distress issues were noted in numerous papers [20, 53, 60–62, 65, 68]. Some of the more specific examples included feeling depressed [8, 40, 49, 51, 55, 63, 64, 67], anxious and fearful [13, 26, 38, 40, 41, 49, 58–60, 74]. Students were also more likely to engage in substance abuse [1, 40, 41, 43, 52, 64], have suicidal ideation [62, 70], have sleep problems [25, 68], feel a loss of confidence [45, 56] and experience shame, isolation and humiliation [15, 39, 57].

Physical wellness issues

Physical wellbeing issues have been either proposed or demonstrated in the papers reviewed. Some of the concerns are related to burnout [8, 14, 66, 67, 73], fatigue [74], psychosomatic or musculoskeletal complaints and the risk of cardiovascular disease [68, 71] and lowered self-perceptions of health [49]. In addition, it was noted that students’ quality of life was moderately affected by patient-initiated aggression, as discerned by issues related to physical functioning, bodily pain and vitality [54].

Following this thematic analysis and using the claims and evidence provided in the articles, we developed a summary diagram (Fig. 2) that shows the potential links between source elements of harassment, types of harassment and purported impact on quality of life. Therefore, we were able to consider the potential deterministic links between the three components.

Fig. 2.

Potential links between

source elements of harassment, types of harassment and purported impact on quality of life

Discussion

In the introduction, we posed the following research questions, “What are medical students’ experiences of harassment in the clinical workplace in relation to their quality of life, and does harassment adversely affect quality of life?” After reviewing the salient literature in this area, we can confirm that the literature supports the existence of a link between harassment and diminished quality of life. However, despite this proposition, our results show a paucity of evidence demonstrating its causality. Hence, based on the current evidence, further definitive work is needed to establish a causal connection between harassment and quality of life. In the following discussion, we consider the findings in terms of what they purportedly suggest and appraise the quality of evidence behind the assertions made.

Purported Links Between Harassment and Quality of Life

Amongst the papers we reviewed, there are enumerable statements and claims made to convincingly indicate that medical students are the victims of harassment [25, 43]. The literature pertaining to the issues of diminished quality of life and burnout are evident [8, 18, 19, 58]. All authors cited in this review contend that there are links between the two sets of phenomena. The conceptual argument indicates that harassment in clinical teaching environments engenders a major source of emotional stress resulting in a depletion of students’ quality of life [25, 38]. This form of abusive behaviour often stems from personnel in positions of power [26, 42, 63, 71, 72] and this is evident, for example, in the area of sexual harassment where men have traditionally had greater power than women [27, 63]. In New Zealand, the current statistics indicate that more female students are enrolled in medical school than male students [76], suggesting that this power imbalance may change. There are further claims suggesting that workplaces engender a culture of harassment, which is developed within professions, sometimes at a subliminal level via the ‘hidden curriculum’ [72]. Harassment and bullying within the workplace adversely affect job fulfilment, job performance and communication with management, which adversely affects learning environments in clinical attachments [68].

In Fig. 2, we have summarised the findings according to the potential source/s of harassment/bullying, the types of harassment/bullying and the effects this could have on quality of life. The issues of quality of evidence and the demonstrable links between the three facets of source, type and impact are discussed in more detail in the next section. Nonetheless, the three facets provide a deterministic argument suggesting that the origin of the harassment lies at its source and hence systems that address the source are more likely to be effective in the long term as opposed to punishing involvement in specific types of harassment after the fact, which may only have short-term effectiveness (i.e. treating the disease rather than the symptoms). The last facet representing the consequences is simply the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, and in this case, the adverse impacts can only be ameliorated using makeshift measures (especially if considered alone), much like repairing wounded soldiers only to send them back out to battle once they have allegedly recovered.

The Quality of Evidence

This scoping review has not only highlighted the problems of harassment in terms of its impact on quality of life, but we have also identified issues associated with poor quality of evidence, lack of ability to demonstrate causal connections and the problems therein with developing convincing arguments.

We were able to find only one study with a high-level research design, namely a prospective randomised crossover study [37] and one study used a mixed methods approach [38]. In the first study, Pottier and colleagues [37] reported that medical students were exposed to stressful incidents, namely determining a diagnosis of either a clinically severe case or a low severity case, and observing a patient who could be either aggressive or co-operative. This resulted in a complex experiment involving four groups. Levels of cognitive appraisal, severity of stress and levels of anxiety were measured. When focussed on the effect of the patient (aggressive or cooperative), the authors found that the presence of aggressive behaviour increased students’ levels of anxiety but at the same time increased their clinical ability and communication scores but did not adversely impact their clinical reasoning. This experiment suggested that medical students may be counterbalancing their responses in specific situations such that if they thought the patients were aggressive, they became more attentive to the task at hand.

In the mixed method study [38], participants were asked to use the Particip8 app to record instances of self-reflection regarding their quality of life, which required students to answer eight questions on a daily basis using World Health Organisation quality of life measures. The qualitative component of the study used grounded theory. The quality of life scores indicated that students had different responses contingent upon which speciality they were assigned to, with general practice yielding the highest scores (best) and surgery the lowest (worst). The experience effect (e.g. whether they had received constructive feedback or not, felt they were bullied or harassed or felt they had been treated fairly, etc.) was shown to be linked with quality of life, thus affirming the link between experiencing harassment and the deleterious effect on quality of life. The qualitative analysis affirmed the feasibility of using the Particip8 app.

In addition, two rigorous reviews were evaluated in this scoping review [13, 20]. However, even though they were able to clearly indicate the prevalence of quality of life issues and harassment, the link between the two facets appeared circumstantial or co-existent rather than causally connected. In contrast, if we focus on the longitudinal survey studies, links between harassment and quality of life were convincingly demonstrated [12, 55]. For example, Haglund and colleagues [12] showed that the experiences of harassment (e.g. rude or belittling comments, verbal abuse or sexual harassment) were associated with increased levels of depression and posttraumatic stress. Hence, while the evidence in this review supports a connection between harassment and quality of life, further work is needed to demonstrate complex interactions involved in the causality argument.

The most common method for collecting data suggesting a link between harassment and quality of life utilised a cross-sectional survey design [14, 25, 27, 39–54]. Upon closer inspection of these articles, it became clear that they tended to report descriptive data alongside likelihood of occurrence statistics to illustrate the connection between the two facets. One exception was the study conducted by Rademakers and colleagues [27] who reported that three out of 10 students stated that sexual harassment (from doctors or patients) led to negative quality of life issues. In the remaining qualitative studies, connections within the commentaries were able to describe instances of harassment being voiced by selected students resulting in some adverse influence on quality of life [15, 56–59]. In the remaining 16 opinion articles [1, 8, 26, 61–73], the link was more assertively stated, although the evidence appeared to be descriptive. Therefore, in such opinion-based evidence, a causal connection was already presumed to exist.

A limitation of this review is that all articles reviewed were in English and the majority of articles reviewed were conducted in North America and Europe, with only a few studies being conducted in Australasia, Nigeria and Pakistan, suggesting a lack of global representation.

Conclusion

There are indications that harassment leads to diminished quality of life. As shown in Fig. 2, the existence of harassment likely stems from various sources and contexts, such as toxic workplaces and maladaptive learning cultures. To tackle the issue of harassment and its impact on quality of life, several initiatives need to be implemented. First, the studies need to employ more rigorous longitudinal designs and analyses to more clearly substantiate the complex layers that exist between harassment and quality of life facets. Second, the subtlety of the links between the facets needs to be teased out. For example, the links between sexual harassment and depression and anxiety are becoming evident; however, links between verbal abuse and quality of life are more complex. Finally, systems also need to be audited and developed to ensure that reporting and amelioration of the effects of harassment are documented.

Notes on Contributors

Marcus A. Henning, MA, MBus, PhD, is an Associate Professor and the corresponding author for this paper, Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland, New Zealand. Email: m.henning@auckland.ac.nz, TEL: 0064 923 7392, FAX: not available.

Josephine Stonyer is a medical student in the MBChB programme, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Yan Chen, PhD, is a Lecturer, Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Benjamin Alsop-ten Hove is a medical student in the MBChB programme, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Fiona Moir, MBChB, MRCGP, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer, General Practice and Primary Healthcare, Population Health, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Craig S. Webster, MSc, PhD, is an Associate Professor, Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Author Contribution

MAH conceptualised and supervised the study. JS was integral to the development of the initial list of papers considered for review. All authors were responsible for preparation, review and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of authors.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This article is a scoping review and hence did not require ethics approval.

Informed Consent

All authors gave their informed consent for inclusion as participating authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wood DF. Bullying and harassment in medical schools. BMJ. 2006;333(7570):664–665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38954.568148.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips SP, Webber J, Imbeau S, et al. Sexual harassment of Canadian medical students: a national survey. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;7:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willis O. Culture of bullying, harassment and discrimination in medicine still widespread, survey suggests. ABC News. 2020. https://www.abc.net.au/news/health/2020-02-10/bullying-harassment-medicine-doctors/11949748.

- 4.Ward L. Surge in bullying complaints from medical students. NZHerald. August 23, 2015.

- 5.Curtis P. Medical students complain of bullying. Guardian News. May 4, 2005.

- 6.Klass P. Walking on Eggshells in Medical Schools. New York Times. September 9, 2019.

- 7.Jenkins TM, Kim J, Hu C, Hickernell JC, Watanaskul S, Yoon JD. Stressing the journey: using life stories to study medical student wellbeing. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(4):767–782. doi: 10.1007/s10459-018-9827-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(12):1613–1622. doi: 10.4065/80.12.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yiu V. Supporting the well-being of medical students. CMAJ. 2005;172(7):889–890. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson R, Cohen C. Dangerous work: The gendered nature of bullying in the context of higher education. Gend Work Organ. 2004;11(2):163–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00227.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner TC, Peetz D, Strachan G, Whitehouse G, Bailey J, Broadbent K. Self-reported harassment and bullying in Australian universities: explaining differences between regional, metropolitan and elite institutions. Journal of Higher Education Policy Management. 2015;37(5):558–571. doi: 10.1080/1360080X.2015.1079400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haglund ME, aan het Rot M, Cooper NS, et al. Resilience in the third year of medical school: a prospective study of the associations between stressful events occurring during clinical rotations and student well-being. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):258–268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.McKenna L, Robinson E, Penman J, Hills D. Factors impacting on psychological wellbeing of international students in the health professions: A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2017;74:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2103–2109. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toman L. Navigating medical culture and LGBTQ identity. Clin Teach. 2019;16(4):335–338. doi: 10.1111/tct.13078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meeberg G. Quality of life: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(1):32–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18010032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whoqol Group Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Commentary: medical student distress: a call to action. Acad Med. 2011;86(7):801–803. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31821da481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354–373. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esan O, Esan A, Folasire A, Oluwajulugbe P. Mental health and wellbeing of medical students in Nigeria: a systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(7–8):661–672. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2019.1677220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gan G-G, Ling Y. Anxiety, depression and quality of life of medical students in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2019;74(1):57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erschens R, Keifenheim KE, Herrmann-Werner A, et al. Professional burnout among medical students: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. 2019;41(2):172–183. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kebede MA, Anbessie B, Ayano G. Prevalence and predictors of depression and anxiety among medical students in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0287-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayala EE, Berry R, Winseman JS, Mason HR. A cross-sectional snapshot of sleep quality and quantity among US medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):664–668. doi: 10.1007/s40596-016-0653-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owoaje ET, Uchendu OC, Ige OK. Experiences of mistreatment among medical students in a university in south west Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2012;15(2):214–219. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.97321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson C. Bullying in surgery. N Z Med J. 2015;128(1424):7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rademakers JJ, van den Muijsenbergh ME, Slappendel G, Lagro-Janssen AL, Borleffs JC. Sexual harassment during clinical clerkships in Dutch medical schools. Med Educ. 2008;42(5):452–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horsley T. Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2019;39(1):54–57. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.University of Canberra. Evidence-based practice in health. 2019. https://canberra.libguides.com/c.php?g=599346&p=4149722.

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Victoor A, Delnoij DM, Friele RD, Rademakers JJ. Determinants of patient choice of healthcare providers: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):272. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chambers D, Wilson P, Thompson C, Harden M. Social network analysis in healthcare settings: a systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e41911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan R. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: data synthesis and analysis. 2013. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/sites/cccrg.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/Analysis.pdf.

- 35.Scientific Software Development GmbH. ATLAS.ti. 2020. https://atlasti.com/.

- 36.Jensen L, Merry A, Webster C, Weller J, Larsson L. Evidence-based strategies for preventing drug administration errors during anaesthesia. Anaesth. 2004;59(5):493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pottier P, Hardouin JB, Dejoie T, et al. Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Stressors on Clinical Skills Performance in Third-Year Medical Students. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1259–1269. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3314-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berryman EK, Leonard DJ, Gray AR, Pinnock R, Taylor B. Self-Reflected Well-Being via a Smartphone App in Clinical Medical Students: Feasibility Study. JMIR Med Educ. 2018;4(1):e7. doi: 10.2196/mededu.9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elnicki DM, Curry RH, Fagan M, et al. Medical students' perspectives on and responses to abuse during the internal medicine clerkship. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(2):92–97. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1402_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fond G, Bourbon A, Auquier P, Micoulaud-Franchi J, Lancon C, Boyer L. Venus and Mars on the benches of the faculty: Influence of gender on mental health and behavior of medical students. Results from the BOURBON national study. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fond G, Bourbon A, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Auquier P, Boyer L, Lançon C. Psychiatry: A discipline at specific risk of mental health issues and addictive behavior? Results from the national BOURBON study. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frank E, Carrera JS, Stratton T, Bickel J, Nora LM. Experiences of belittlement and harassment and their correlates among medical students in the United States: longitudinal survey. BMJ. 2006;333(7570):682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38924.722037.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapoor S, Ajinkya S, Jadhav PR. Bullying and victimization trends in undergraduate medical students - a self-reported cross-sectional observational survey. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(2):VC05–VC08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Kolkijkovin V, Phutathum S, Natetaweewat N, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in medical students at Faculty of Medicine Vajira Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2019;102(9):104–108. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maida AM, Vasquez A, Herskovic V, et al. A report on student abuse during medical training. Med Teach. 2003;25(5):497–501. doi: 10.1080/01421590310001606317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McEvoy JW, Shatzer JH, Desai SV, Wright SM. Questioning Style and Pimping in Clinical Education: A Quantitative Score Derived from a Survey of Internal Medicine Teaching Faculty. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):53–64. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2018.1481752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oku A, Oku O, Owoaje E, Monjok E. An Assessment of Mental Health Status of Undergraduate Medical Trainees in the University of Calabar, Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(2):356–362. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2015.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paice E, Aitken M, Houghton A, Firth-Cozens J. Bullying among doctors in training: Cross sectional questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2004;329(7467):658–659. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38133.502569.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Przedworski JM, Dovidio JF, Hardeman RR, et al. A Comparison of the Mental Health and Well-Being of Sexual Minority and Heterosexual First-Year Medical Students: A Report From the Medical Student CHANGE Study. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):652–659. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qamar K, Khan NS, Bashir Kiani MR. Factors associated with stress among medical students. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(7):753–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romo-Nava F, Bobadilla-Espinosa RI, Tafoya SA, et al. Major depressive disorder in Mexican medical students and associated factors: A focus on current and past abuse experiences. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shoukat S, Anis M, Kella DK, et al. Prevalence of mistreatment or belittlement among medical students–a cross sectional survey at a private medical school in Karachi, Pakistan. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 2010;5(10):e13429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vargas EA, Brassel ST, Cortina LM, Settles IH, Johnson TRB, Jagsi R. #MedToo: a large-scale examination of the incidence and impact of sexual harassment of physicians and other faculty at an academic medical center. J Womens Health. 2002(pagination). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Xie Z, Li J, Chen Y, Cui K. The effects of patients initiated aggression on Chinese medical students' career planning. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):849. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2810-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardeman RR, Przedworski JM, Burke S, et al. Association Between Perceived Medical School Diversity Climate and Change in Depressive Symptoms Among Medical Students: A Report from the Medical Student CHANGE Study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2016;108(4):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daud S, Farid RR, Mahboob K, Ahsan Q, Tarin E. The wounded healers: A qualitative study of stress in medical students. Pakistan Journal of Medical and Health Sciences. 2016;10(1):168–173. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doulougeri K, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery A. (How) do medical students regulate their emotions? BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0832-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monrouxe LV, Rees CE. "It's just a clash of cultures": emotional talk within medical students' narratives of professionalism dilemmas. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2012;17(5):671–701. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9342-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. "A morning since eight of just pure grill": a multischool qualitative study of student abuse. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1374–1382. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182303c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aysola J, Barg FK, Martinez AB, et al. Perceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations: A Qualitative Narrative Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181003. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Botha D. Are we at risk of losing the soul of medicine? Can J Anaesth. 2017;64(2):122–127. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0776-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coopes A. Operate with respect: How Australia is confronting sexual harassment of trainees. BMJ (Online). 2016;354 (no pagination). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1589–1591. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1809846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elnicki D. Learning with emotion: Which emotions and learning what? Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1111. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.George DR, Green MJ. Lessons learned from comics produced by medical students art of darkness. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2345–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grissinger M. A compelling call to action to establish a culture of respect. P T. 2015;40(8):480–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kalaichandran A, Lakoff D. We must also think about trainees and the role of culture in physician mental health. CMAJ. 2019;191(36):E1009. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.72749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parikh JR, Harolds JA, Bluth EI. Workplace Bullying in Radiology and Radiation Oncology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(8):1089–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Roberts LW. Hard duty. Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(4):274–277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.4.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schernhammer E. Taking their own lives - The high rate of physician suicide. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(24):2473–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh T, Singh A. Abusive culture in medical education: Mentors must mend their ways. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2018;34(2):145–147. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.236659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stone LE, Douglas K, Mitchell I, Raphael B. Sexual abuse of doctors by doctors: Professionalism, complexity and the potential for healing: Sexual abuse in the medical profession is a complex, multifaceted problem that needs evidence-based solutions. Med J Aust. 2015;203(4):170–171.e171. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ward S, Outram S. Medicine: in need of culture change. Intern Med J. 2016;46(1):112–116. doi: 10.1111/imj.12954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perry SP, Hardeman R, Burke SE, Cunningham B, Burgess DJ, van Ryn M. The Impact of Everyday Discrimination and Racial Identity Centrality on African American Medical Student Well-Being: a Report from the Medical Student CHANGE Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(3):519–526. doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0170-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roberts LW, Warner TD, Lyketsos C, Frank E, Ganzini L, Carter D. Perceptions of academic vulnerability associated with personal illness: a study of 1,027 students at nine medical schools. Collaborative Research Group on Medical Student Health. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(1):1–15. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Poole PJ, Moriarty HJ, Wearn AM, Wilkinson TJ, Weller J. Medical student selection in New Zealand: looking to the future. NZ Med J. 2009;122(1306):88–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]