Abstract

Introduction

Burnout is considered to be at the opposite end of the continuum from engagement. People who experience burnout first go through various intermediate patterns that lead to burnout, which in medical students is associated with reduced empathy, intention to leave school, and suicidal ideation. Thus, understanding how to mitigate burnout is of primary importance. In this study, we investigate if students’ positive perceptions of the educational program’s alignment with adult education principles decreased symptoms suggestive of typical patterns of intermediate burnout.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study of all currently enrolled Duke-NUS Medical School students in Singapore (n = 238). An electronic questionnaire contained demographic questions and additional measures for factors known to be associated with burnout, including depression, anxiety, social support, and workload. In addition, we measured students’ perceptions of how well the educational program aligned with adult learning principles by using a modified version of the Andragogical Practices Inventory (API) to suit medical education. An intermediate pattern of burnout was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Using logistic regression, we then assessed the unique association between the presence of an intermediate pattern of burnout with students’ perceptions of the educational program’s alignment with adult learning principles.

Results

The survey response rate was 52%. Overall, 76% (95% CI 67–84%) displayed symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout. Perceptions of the educational program’s alignment with adult learning principles were found to be inversely related to the pattern of burnout after controlling for depression, anxiety, and subjective workload.

Discussion and Conclusion

Though adult learning theory is the subject of rich debate, the results of this study suggest that promoting educational activities that are aligned with adult learning principles may help to ultimately reduce the risk of burnout in medical school students.

Keywords: Education environment, Evaluation, Medical education research, Psychometrics

Background

Burnout is a well-studied phenomenon in the medical profession, which is considered to be at the opposite end of the spectrum from being fully engaged. Maslach defined burnout as “… a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job…defined by the three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy.” Emotional exhaustion is the individual component of burnout where the person feels overextended and depleted of their resources. Cynicism, or depersonalization, is the interpersonal component of burnout where the individual exhibits inappropriate responses to various aspects of the job and misconstrued by others to be negative, callous, or excessively detached. Inefficacy is the self-evaluation component of burnout where individual perceives themselves as incompetent and devalues their own personal accomplishments. Evidence suggests that people who experience burnout first go through various intermediate patterns that ultimately lead to burnout [1].

The public health significance of burnout in working professionals results from its association with adverse outcomes for the affected individual as well as for the workplace. Burnout has been linked to poor psychological health, inadequate coping, interpersonal dysfunction, and also associated with professional issues such as absenteeism, lower productivity, and job dissatisfaction [1].

Certain occupations predispose individuals to burnout because of the nature of work. In particular, occupations that require interactions with other people are at risk. The medical profession, therefore, is an example of a profession vulnerable to burnout, as the primary clients of healthcare professionals come from a vulnerable population—the sick and the disabled [2]. Burnout has been described across all levels of a medical career, from students [3], residents [4, 5], senior consultants [6], and among allied health professionals [7]. The most concerning feature of burnout is its deleterious impact on the “burned out” individual. Typical consequences of burnout among students include lower levels of empathy [4], a greater intention to leave the educational institution [8], and a higher likelihood of suicidal ideation [3]. Among physicians, burnout has been shown to lead to sub-optimal patient care [9] and increased perceived medical errors [10]. In contrast, for physicians, a sense of well-being has been found to be important for upholding the quality of care provided to patients in clinical settings [11]. The potential negative impact of burnout within the medical profession is highlighted by Jennings, who stated that “…burnout is not a benign rite of passage but a painful and disorienting experience with serious potential consequences for a student’s health, professionalism, and patient care.” [12]

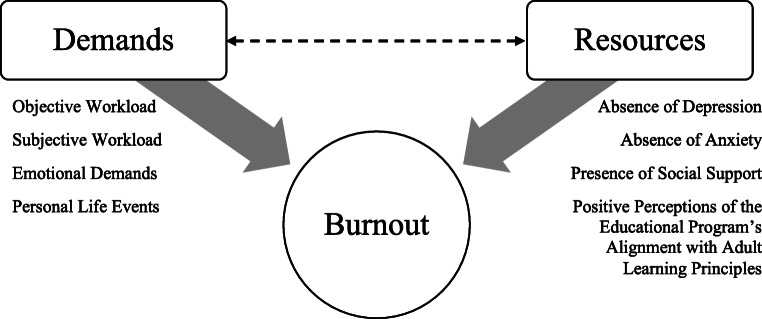

A conceptual model of burnout based on the Job Demands-Resources Model is shown in Fig. 1. The model, as adapted for medical students, categorizes risk factors into either demands or resources and predicts that demands and resources interact and modulate one another. Demands of medical education include the student’s workload, the emotional demands of interactions with colleagues or patients, and also personal life events [3]. Resources refer to factors available to the individual for support. Such psychosocial factors include the absence of depression or anxiety and the presence of good social support. From the point of view of this model, one potential resource to combat the development of medical student burnout may be the student’s perceptions of the educational experience itself.

Fig. 1.

A conceptual model for medical student burnout based on the Job Demands-Resources Model

Adult learning theory, or “andragogy,” is a framework used for the development of educational processes that support learning [13]. Adult learning theory posits that six basic principles are best suited for educational programs for adults. They are the following: first, the learner’s motivation is internal. Second, the learner’s prior experiences serve as a resource for further learning. Third, the learner needs to know the relevance of the subject material. Fourth, the learner is prepared to learn what they need to cope with different situations. Fifth, the learner’s self-concept is that of being self-directed as opposed to being dependent. Sixth, the learner’s orientation to learning is problem-centered as opposed to subject-centered. These principles squarely focus the educational process away from the teacher and on to the learner.

Educational practices based on adult learning theory reinforce the independence of the learner and their learning needs. As such, the central hypothesis of our research was that reinforcing these adult learning internal characteristics of the individual has a beneficial effect on their internal coping mechanisms in the face of chronic stressors. In particular, we hypothesized that the depth and breadth of medical education are better conducted when done in a manner that caters, rather than conflicts, to their learning needs. We posit that this alignment between the educational program and the adult learner’s tendencies builds up resilience and thus, they become less likely to develop burnout as they progress through medical education. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate if students’ positive perceptions of the educational program’s alignment with adult learning principles is associated with decreased symptoms suggestive of typical patterns of intermediate burnout.

Methods

Setting and Subjects

A cross-sectional study of all currently enrolled medical students (n = 238) from Duke-NUS Medical School was conducted using survey methodology. Duke-NUS is an American style, graduate-entry, allopathic medical school in Singapore. This study was approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board.

Survey Instrument

The survey contained demographic questions and screening tests that have been previously suggested as valid markers of each factor in the conceptual model as shown in Fig. 1.

Intermediate patterns of burnout were measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) which is the most widely used instrument for measuring burnout and has been validated and utilized in several populations including physicians and medical students [3, 14–16]. The MBI evaluates burnout using three subscales, and a high score on either the emotional exhaustion or depersonalization subscale suggested an intermediate pattern of burnout [1]. To assess students’ perceptions of how well the educational program aligns with adult learning principles, we used a modified version of the Andragogical Practices Inventory (API), an instrument that is the most comprehensive measure of student perceptions of andragogical principles that have been published to date [17]. For this study, we modified the API by retaining 21 questions for measuring perceptions of andragogical principles but omitting the remaining 22 questions regarding andragogical process design elements. Symptoms of depression were assessed using the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D). The CES-D is a widely used screening tool for depression and has been previously used in the medical student population [3]. Anxiety symptoms were measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Screener (GAD-7), a self-report questionnaire previously used in primary care settings [18]. Current evidence supports the reliability and validity of the GAD-7 as a measure of anxiety in the general population [19]. To measure the availability of social support, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was used [20]. The MSPSS has been shown to have good reliability and validity in a broad range of research participant groups [20]. Lastly, emotional demands were measured with a subscale of the Questionnaire Experience and Evaluation of Work (QEEW) [21]. The QEEW has been used successfully in previous studies examining factors contributing to burnout [22].

The survey was created on an online platform and a link to the survey was sent out to the Duke-NUS medical student mailing list. Two reminder e-mails were sent out after the initial invitation e-mail, sent 1 and 2 weeks afterwards, respectively.

To assess the internal consistency reliability of each survey instrument, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each individual scale (or subscale where appropriate). Summary statistics of survey instruments are reported for all responders in terms of numbers and percentages or mean scores and standard deviations, where appropriate. As part of the descriptive process, we also conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of the 21 API items in order to ascertain whether the previously reported factor structure would be replicated in our particular sample.

Reliability Statistics

The internal reliability of survey instruments used in the study was compared with previous values found in the literature and results shown in Table 1. Overall, our obtained reliability statistics (Cronbach’s alpha) closely matched previously reported values.

Table 1.

Calculated reliability statistics of survey instruments and comparison with previously reported values

| Scale | Number of items | Obtained Cronbach’s alpha | Previously reported alpha | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBI | 16 | Iwanicki & Schwab [23] | ||

| Emotional Exhaustion | 5 | 0.90 | 0.90 | |

| Depersonalization | 5 | 0.85 | 0.76 | |

| Personal accomplishment | 6 | 0.87 | 0.76 | |

| CES-D | 20 | 0.92 | 0.85–0.90 | Radloff [24] |

| GAD-7 | 7 | 0.93 | 0.79–0.91 | Dear [25] |

| API | 21 | Holton et al. [26] | ||

| Self-directedness | 3 | 0.80 | 0.73 | |

| Need to know | 4 | 0.83 | 0.76 | |

| Readiness | 3 | 0.86 | 0.81 | |

| Experience | 3 | 0.89 | 0.84 | |

| Motivation | 8 | 0.92 | 0.93 | |

| MSPSS | 12 | 0.93 | 0.88–0.92 | Zimet et al. [27] |

| Workload | 2 | 0.54 | 0.56 | Jacobs & Dodd [28] |

| Emotional demands | 7 | 0.82 | 0.85 | van Veldhoven et al. [29] |

MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; CES-D, Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Screener; API, Andragogical Practices Inventory; MSPSS, Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of API Items

In order to determine whether the previously reported factor structure for the Andragogical Practices Inventory (API) items that measured perceptions of adult learning principles was replicated in the present sample, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using covariance structure analysis via PROC CALIS in SAS version 9.2. An a priori factor structure was specified based on the factors previously reported by Holton and colleagues, the developers of the API [17]. To make the test as rigorous as possible, both the factor structure itself (including the factor intercorrelations) and the factor loadings for each item were specified within the model. Under these conservative conditions, we observed that the prespecified model was a poor fit to the sample data, χ2 (179) = 552.48, p < 0.001. Examination of modification indices revealed that the inter-factor correlations within our sample were somewhat higher than those reported by Holton and colleagues, which substantially reduced the confirmatory model’s goodness of fit. We then conducted a follow-up CFA in which the factor intercorrelations were left free to vary. This analysis resulted in a significantly better fit to the present sample data, χ2 (182) = 251.11, p < 0.001. Examination of additional fit indices suggested that the original factor structure for the API items measuring adult learning principles was a marginally acceptable fit to the present data, CFI = 0.89, NFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.08. Based on this second CFA, we concluded that the API was appropriate for inclusion in our subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis for this study was conducted in three phases. The first phase of analysis described the sample, with summaries of demographic data and the different survey instruments. For demographic data, the following are reported: responders, year in medical school, age range, gender, relationship status, highest education achievement, part-time work and hours worked, and previous psychiatric history in terms of numbers and percentages.

The second phase of analysis identified potential factors associated with the development of burnout. Categorical variables such as demographic data and continuous variables such as API scores were compared between groups of students with no or high symptoms suggestive of an intermediate patterns of burnout and tested for statistical significance with chi-square and independent samples t tests, respectively. Associated factors with a p value less than 0.10 were retained for multivariable analyses. To show the direction of change for MBI subscale scores and total API scores, linear regression analyses also were conducted.

The third and final phase of analysis sought to determine the unique contribution of student perceptions of the educational program (over and above the other resources and demands postulated by our model) in predicting medical students’ self-reports of symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout. Binary logistic regression analysis was conducted with significant variables identified in the second phase of the study. A backward conditional stepwise entry method was used as a conservative data-analytic strategy. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), with the level of significance set a priori at < 0.05.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A total of 124 students responded to the survey from a possible 238 students, yielding a response rate of 52%. Demographic data are shown in Table 2. Most of the responses were obtained from first-year and third-year medical students. There was no significant difference between the number of male and female responders (p = 0.47). A majority of the responders were single, did not perform any part-time work, and also did not report any psychiatric history.

Table 2.

Demographic data of survey responders

| Responders (n = 124) | Responders/Population (n = 238) | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Year in medical school | ||

| 1 | 39 (33.3) | 39/62 (63) |

| 2 | 21 (17.9) | 21/56 (38) |

| 3 | 37 (31.6) | 37/50 (74) |

| 4 | 14 (12.0) | 14/49 (28) |

| PhD | 6 (4.8) | 6/21 (28) |

| Age | ||

| 21–29 | 103 (87.3) | 103/202 (51) |

| 30–39 | 15 (12.7) | 15/15 (100) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 55 (47) | 55/120 (46) |

| Male | 62 (53) | 62/117 (53) |

| Highest educational achievement | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 97 (83.6) | 97/169 (57.4) |

| Master’s degree | 11 (9.5) | 11/3 1(35.5) |

| Doctor of philosophy | 8 (6.9) | 8/17 (47) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 17 (14.8) | – |

| Single | 98 (85.2) | |

| Part-time work | ||

| No | 109 (93.2) | – |

| Yes | 8 (6.8) | |

| Psychiatric history | ||

| No | 111 (97.4) | – |

| Yes | 3 (2.6) | |

Descriptive statistics for survey instruments are shown in Table 3. MBI scores are listed by subscale. A high score in emotional exhaustion or depersonalization indicated symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout. Using these definitions, a majority of responders met the previously established statistical criterion for the intermediate pattern of burnout (N = 79, 76%; 95% CI 67.7–84.2). Depression and anxiety also were prevalent among responders, with 36.2% (95% CI 27.7, 44.7) and 9.7% (95% CI 4.5, 14.9) of students screening positive for major depression and clinically significant anxiety, respectively. Responders reported a high level of social support and a low subjective workload, despite the majority allocating 22 or more hours to their course of study every week. Score distribution histograms and descriptive statistics for API and emotional demands are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

Descriptive data of survey instruments

| Mean (SD) | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Burnout | ||

| Emotional exhaustion | 16.4 ± 7.3 | |

| Low | 27 (26.0) | |

| Moderate | 20 (19.2) | |

| High | 57 (54.8) | |

| Depersonalization | 11.7 ± 6.9 | |

| Low | 25 (24.5) | |

| Moderate | 24 (23.5) | |

| High | 53 (52.0) | |

| Personal accomplishment | 22.7 ± 7.1 | |

| Low | 49 (47.6) | |

| Moderate | 38 (36.9) | |

| High | 16 (15.5) | |

| Have burnout | 79 (76) | |

| Depression | ||

| Screen negative | 67 (63.8) | |

| Screen positive | 38 (36.2) | |

| Overall | 19.4 ± 11.9 | |

| Anxiety | ||

| Low | 53 (51.5) | |

| Mild | 30 (29.1) | |

| Moderate | 10 (9.7) | |

| Severe | 10 (9.7) | |

| Overall | 5.80 ± 5.4 | |

| API | ||

| Self-directedness | 11.3 ± 2.3 | |

| Need to know | 16.1 ± 2.7 | |

| Readiness | 10.8 ± 2.6 | |

| Experience | 11.4 ± 2.6 | |

| Motivation | 31.0 ± 5.4 | |

| Overall | 80.6 ± 13.7 | |

| MSPSS | ||

| Significant other | 5.1 ± 1.8 | |

| Family | 5.3 ± 1.3 | |

| Friends | 5.4 ± 1.2 | |

| Total | 5.3 ± 1.2 | |

| Workload | ||

| Subjective workload | ||

| Low | 48 (50.5) | |

| Moderate | 25 (26.3) | |

| High | 22 (23.2) | |

| Objective workload | ||

| 8 to 9 h | 2 (2.1) | |

| 10 to 11 h | 3 (3.1) | |

| 12 to 13 h | 8 (8.2) | |

| 14 to 15 h | 3 (3.1) | |

| 16 to 17 h | 2 (2.1) | |

| 18 to 19 h | 1 (1.0) | |

| 20 to 21 h | 1 (1.0) | |

| 22 or more hours | 77 (79.4) | |

| Emotional demands | ||

| Mean score | 15.6 ± 3.8 | |

Fig. 2.

Score distribution for the Andragogical Principles Inventory and Emotional Demands

We compared demographics and explanatory variables between responders with symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout. Results of these comparative analyses are shown in Tables 4 and 5. As the Duke-NUS Medical School curriculum is somewhat unique within American style medical schools, we compared students with and without intermediate patterns of burnout based on their primary focus of study, rather than a year of study. At Duke-NUS, year 1 represents the basic sciences, year 2 represents the clinical clerkships, year 3 represents research, and year 4 represents a return to the clinical setting. No significant association was found between any demographic variable and the presence of an intermediate pattern of burnout in responders. However, higher self-reported levels of depression, anxiety, and subjective workload were associated with the presence of high symptoms of burnout. Furthermore, a less favorable perception of adult learning principles and higher emotional demands also were associated with the presence of symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout. Social support and objective workload were found not to differ significantly between groups and thus excluded from further analysis.

Table 4.

Comparisons between demographic data and burnout

| Intermediate pattern of burnout | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 25) | Yes (n = 79) | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Focus of current study | ||||

| Basic sciences | 8 (32%) | 26 (33.3%) | 0.550a | – |

| Clinical sciences | 5 (20%) | 23 (29.5%) | ||

| Research | 12 (48%) | 29 (37.2%) | ||

| Age | ||||

| 21–29 | 20 (80%) | 70 (88.6%) | 0.272a | 0.51 (0.16–1.71) |

| 30–39 | 5 (20%) | 9 (11.4%) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 14 (56%) | 36 (46.2%) | 0.391a | 1.46 (0.60–3.68) |

| Male | 11 (44%) | 42 (53.8%) | ||

| Relationship status | ||||

| Married | 6 (25%) | 10 (12.8%) | 0.151a | 2.27 (0.73–7.07) |

| Single | 18 (75%) | 68 (87.2%) | ||

| Highest educational achievement | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 20 (80%) | 66 (83.5%) | 0.683a | 0.79 (0.25–2.48) |

| Master’s degree or doctor of philosophy | 5 (20%) | 13 (16.5%) | ||

| Part-time work | ||||

| Yes | 2 (8%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.771a | 1.29 (0.23–7.08) |

| No | 23 (92%) | 74 (93.7%) | ||

| Psychiatric history | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0.430b | – |

| No | 25 (100%) | 75 (96.2%) | ||

aChi-square test

bFisher’s exact test (one-sided)

Table 5.

Comparisons between survey instruments and burnout

| Intermediate pattern of burnout | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 25) | Yes (n = 79) | p value | |

| Depression | |||

| Screen positive | 3 (12%) | 35 (44.3%) | 0.003a |

| Anxiety | |||

| Low | 22 (91.7%) | 30 (38.5%) | < 0.001a |

| Mild | 2 (8.3%) | 28 (35.9%) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0%) | 10 (12.8%) | |

| Severe | 0 (0%) | 10 (12.8%) | |

| API | |||

| Self-directedness | 12.4 ± 1.5 | 11.01 ± 2.5 | 0.002b |

| Need to know | 17.1 ± 1.9 | 15.76 ± 2.9 | 0.036b |

| Readiness | 12.2 ± 1.9 | 10.38 ± 2.7 | 0.001b |

| Experience | 12.3 ± 2.5 | 11.14 ± 2.5 | 0.068b |

| Motivation | 33.7 ± 4.3 | 30.22 ± 5.5 | 0.007b |

| Overall | 87.7 ± 10.1 | 78.52 ± 14.1 | 0.005b |

| MSPSS | |||

| Significant other | 5.2 ± 1.6 | 5.14 ± 1.9 | 0.869b |

| Family | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.15 ± 1.3 | 0.041b |

| Friends | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 5.37 ± 1.2 | 0.133b |

| Overall | 5.6 ± 1.2 | 5.23 ± 1.2 | 0.202b |

| Workload | |||

| Subjective workload | |||

| Low | 17 (81%) | 31 (41.9%) | 0.003a |

| Moderate | 4 (19%) | 21 (28.4%) | |

| High | 0 (0%) | 22 (29.7%) | |

| Objective workload | |||

| Less than 22 h | 2 (9.5%) | 18 (24%) | 0.149a |

| 22 or more hours | 19 (90.5%) | 57 (76%) | |

| Emotional demands | |||

| Mean score | 14.1 ± 2.8 | 16.0 ± 4.0 | 0.041b |

aChi-square test

bIndependent samples t test

To quantify the association between student perceptions of andragogical principles and an intermediate pattern of burnout, a linear regression analysis was conducted between API scores and MBI subscale scores. Results are shown in Fig. 3. A statistically significant inverse association between students’ perceptions of adult learning principles and two burnout subscales, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, was observed. Moreover, favorable perceptions of andragogical principles were associated with a higher score on the personal efficacy subscale.

Fig. 3.

Linear regression plots of MBI subscale scores and total API scores

Multivariable Analysis

Finally, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict the presence of an intermediate pattern of burnout for 95 responders after accounting for missing data using significant variables identified in the previous phase of analysis. A backward stepwise regression model was constructed and results presented in Table 6. The initial variables included in the model were depression, anxiety, emotional demands, subjective workload, and andragogical perceptions. The analysis determined that anxiety, subjective workload, and andragogical perceptions were statistically significant predictors of the presence of symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout. Depression and emotional demands were not found to be significant, although it should be noted that the moderate levels of intercorrelation among the predictor variables require that we interpret these findings cautiously.

Table 6.

Results of binary logistic regression analysis for predicting the presence of the intermediate pattern of burnout

| B | Standard Error (S.E.) | Wald | df | p value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Depression | 0.915 | 0.937 | 0.954 | 1 | 0.329 | 2.50 (0.40–15.64) |

| Anxiety | 2.422 | 0.838 | 8.346 | 1 | 0.004 | 11.27 (2.18–58.26) |

| Emotional demands | 0.049 | 0.098 | 0.246 | 1 | 0.620 | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) |

| Subjective workload | 1.626 | 0.611 | 7.070 | 1 | 0.008 | 5.08 (1.53–16.85) |

| API | − 0.054 | 0.027 | 3.911 | 1 | 0.048 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Depression | 0.926 | 0.937 | 0.977 | 1 | 0.323 | 2.52 (0.40–15.82) |

| Anxiety | 2.498 | 0.830 | 9.068 | 1 | 0.003 | 12.16 (2.39–61.80) |

| Subjective workload | 1.621 | 0.613 | 6.985 | 1 | 0.008 | 5.06 (1.52–16.82) |

| API | − 0.053 | 0.027 | 3.811 | 1 | 0.051 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) |

Discussion

The results of this study show that positive perceptions of the educational program in terms of aligning with adult learning principles may play an important role in protecting against burnout symptoms among medical students. This finding is important for educators as it provides support for the use of an adult learning theory as a framework for medical education. Though the effects of an adult learning approach to teaching on learning outcomes are a subject of rich debate, there are reports in the literature suggesting that an adult learning approach improves student satisfaction with the instructor and the course [30]. Therefore, our results add to the body of knowledge surrounding adult learning theory and highlight its potential role in enhancing student well-being. This observed association between positive educational perceptions and low symptoms suggestive of burnout may stem from the method that adult learning theory employs in engaging the adult learner. The adult learning approach reinforces internal characteristics of the adult learner, enabling effective delivery of the learning experience. It is possible that reinforcement of these internal characteristics extends beyond learning and into the individual learner’s well-being. Through the cultivation of a learner’s inherent characteristics to solve various problems independently, adult learning theory may also bring about the development of resilience in an individual. This notion then pushes for the development of curriculum and learning environments that cater to the adult learner, as it possesses positive effects for student well-being.

Another important finding in our study was the high prevalence of symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout, depression, and, to a lesser extent, anxiety in our medical student sample. In this study, the percentage of responders with high burnout symptoms was 76%. This figure is much higher than that of similar studies in US medical students, which reported figures of 45% and 49.6% [3]. However, our study involved several key differences from the aforementioned studies. Dyrbye and colleagues used the MBI Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) which is a 22-item version of the MBI and has an emphasis on service relationships. Despite having additional items in the emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment subscales, the MBI-HSS uses different values for categorizing subscale scores as low, average, or high depending on the occupation surveyed. Previous studies used the cutoff scores for medical professionals, which are substantially higher than that of the MBI student survey (e.g., for high emotional exhaustion, 27 compared with 16 for MBI-HSS and MBI-SS, respectively). Since medical students are a population separate from other post-secondary learners and working medical professionals, it may be prudent to consider the prevalence of burnout separately for each population. Furthermore, as medical training encompasses both classroom-based and hands-on teaching, it is challenging to rely on a single instrument for evaluating burnout given the possible differences in these two teaching environments. However, this observation also suggests new avenues for burnout research in medical students in terms of identifying a tool or method which best evaluates symptoms across all stages of training.

The prevalence of major depression in our study (using the standard CES-D criterion score) was 36.2%, which is lower than previously reported figures of 53.5% and 56% in other studies of medical students [3, 31]. Although different questionnaires were used for assessing student risk of major depression, both instruments used were validated in the medical student population [32, 33]. As the prevalence of depression in the general population of Singapore and the USA is similar [34, 35], we suspect that this discrepancy is due to other factors besides cultural differences. Interestingly, we find that screening positive for major depression is not a significant predictive variable for high burnout symptoms. Previous studies have shown that burnout and depression are separate clinical entities [36], and some even attribute burnout to be a contributing factor to the development of depression [3]. However, causality is difficult to demonstrate with cross-sectional studies, and it may be that depression and burnout influence one another as different manifestations of an individual’s mental distress. Nevertheless, depression itself is a serious mental illness that demands attention and treatment.

Surprisingly, anxiety was found to be strongly predictive of burnout symptoms. Although previous work has found that anxiety is strongly correlated with burnout [37], it has not been emphasized in contemporary burnout research, particularly within samples of medical students. Turnipseed suggested that the presence of anxiety sensitizes an individual to distressing stimuli regardless of the social situation, thus predisposing the individual to develop burnout [38]. A state of anxiety would no doubt expedite the rate of emotional exhaustion and pre-occupation with anxiety would lead to an individual to discount their own personal accomplishments. Subjective workload was the last of the factors found to be significantly predictive of burnout symptoms after logistic regression analysis. This association is perhaps best interpreted with the definition of burnout as a prolonged response to chronic stressors. Intuitively, we surmise that if one rates their own stressors as low, that one is better equipped to manage those stressors and thus less likely to develop burnout. However, we note that the internal reliability of the subjective workload scale was relatively low at 0.54, consistent with previously reported values [39]. Further improvement can be made to increase the reliability of this construct such as asking the student to compare their current workload with that of their highest workload to date.

We note that our study has several limitations. First, cross-sectional study design is not able to demonstrate causality between our hypothesized explanatory factors and the development of burnout in medical students. Although some longitudinal studies have examined mental health in medical students [40, 41], these studies focused on trends of mental distress over time. A longitudinal study to look at causation would not only prove valuable in establishing local trends of student mental health but also would serve as an effective tool in evaluating current methods of instruction in terms of student well-being. Second, our response rate among Duke-NUS medical students was 52%. Although comparable with similar studies in medical students and physicians [31, 42, 43], a higher response rate would have provided more accurate data regarding the prevalence of distress within the medical student population. Nevertheless, even if all non-responders exhibited low burnout and screened negative for major depression, we would have obtained a prevalence of approximately 33% and 16% for intermediate patterns of burnout and depression, respectively. This figure remains a concern overall, and the outcomes of these conditions definitely deserve attention on an individual basis. Furthermore, and importantly, we note that there have been some concerns raised regarding how learners’ previous educational experiences impact their response to adult learning educational experiences. For example, Pew suggests that some students have difficulty with educational experiences based on adult learning theory if they were previously exposed to teacher-reliant educational experiences [44]. We believe this is an important point worthy of future research.

Conclusions

In summary, we observed an inverse association between perceptions of the educational program in terms of its alignment with adult learning principles and symptoms suggestive of an intermediate pattern of burnout in medical students. This study also found that anxiety and subjective workload may contribute to the development of burnout, after controlling statistically for other factors. We reported on the prevalence of mental health issues in the medical student population, namely intermediate patterns of burnout, depression, and anxiety, and discussed reasons for their pervasiveness and the issues surrounding them. Finally, we recommend measures that may be taken to enhance student well-being during medical training.

Authors’ contributions

• DJS designed and conducted the study, collected data, analyzed data, and is the primary author of the manuscript.

• TJS analyzed data and co-authored sections of the manuscript.

• SC conceived and designed the study, analyzed data, and co-authored sections of the manuscript.

• All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National University of Singapore (B-15-090E).

Informed consent

This study was exempted from informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: a new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burn Res. 2016;3(4):89–10. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felton J. Burnout as a clinical entity—its importance in health care workers. Occup Med. 1998;48:237–250. doi: 10.1093/occmed/48.4.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Personal life events and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Acad Med. 2006;81:374–384. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talih F, Warakian R, Ajaltouni J, Shehab AA, Tamim H. Correlates of Depression and Burnout Among Residents in a Lebanese Academic Medical Center: a Cross-Sectional Study. Acad Psychiatry : the journal of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and the Association for Academic Psychiatry. 2015;40:38–45. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramirez A, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM, Leaning MS, Snashall DC, Timothy AR. Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:1263–1269. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siefert K, Jayaratne S, Chess WA. Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover in health care social workers. Health Soc Work. 1991;16:193–202. doi: 10.1093/hsw/16.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLuca A. (2004) Burnout, coping, and intention to leave college in undergraduate students: a cross-ethnic perspective. (Hofstra University.

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West CP, Huschka MM, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Kolars JC, Habermann TM, Shanafelt TD. Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. Jama. 2006;296:1071–1078. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace JE, Lemaire J. Physician well-being and quality of patient care: an exploratory study of the missing link. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14:545–552. doi: 10.1080/13548500903012871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennings M. Medical student burnout: interdisciplinary exploration and analysis. J Med Human. 2009;30:253–269. doi: 10.1007/s10912-009-9093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles M (1973) The adult learner: a neglected species

- 14.Cordes CL, Dougherty TW. A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Acad Manag Rev. 1993;18:621–656. doi: 10.2307/258593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR, Rudisill JR. Validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42:488–492. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198605)42:3<488::AID-JCLP2270420315>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trufelli D, et al. Burnout in cancer professionals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care. 2008;17:524–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holton EF, Wilson LS, Bates RA. Toward development of a generalized instrument to measure andragogy. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2009;20:169–193. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266–274. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dear BF, Titov N, Sunderland M, McMillan D, Anderson T, Lorian C, Robinson E. Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40:216–227. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veldhoven MJPMV (2009) Psychosociale arbeidsbelasting en werkstress. Swets & Zeitlinger

- 22.Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Taris TW, Schaufeli WB, Schreurs PJ. A multigroup analysis of the Job Demands-Resources Model in four home care organizations. Int J Stress Manag. 2003;10:16–38. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwanicki EF, Schwab RL. A Cross Validation Study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory12. Educational and psychological measurement 1981;41:1167–1174.

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement 1977;1:385–401.

- 25.Dear BF et al. Psychometric comparison of the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for measuring response during treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Cognitive behaviour therapy 2011;40:216–227. 10.1080/16506073.2011.582138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Holton EF, Wilson LS & Bates RA. Toward development of a generalized instrument to measure andragogy. Human Resource Development Quarterly 2009;20:169–193.

- 27.Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S & Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of personality assessment 1990;55:610–617. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Jacobs SR & Dodd D. Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. Journal of College Student Development 2003;44:291–303.

- 29.van Veldhoven M, de Haan S, & Vethman A, Handleiding VBBA. (SKB Vragenlijst Services Amsterdam,

- 30.Wilson LS (2005) A test of andragogy in a post-secondary educational setting, San Jose State University.

- 31.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Power DV, Eacker A, Harper W, Durning S, Moutier C, Szydlo DW, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:334–341. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-5-200809020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosal MC, et al. A longitudinal study of students’ depression at one medical school. Acad Med: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1997;72:542–546. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosley TH, Jr, et al. Stress, coping, and well-being among third-year medical students. Acad Med: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1994;69:765–767. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199409000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chong SA. A population-based survey of mental disorders in Singapore. Ann Acad Med-Singapore. 2012;41:49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pratt LA & Brody DJ (2008) Depression in the United States household population, 2005-2006. NCHS data brief, 1-8. [PubMed]

- 36.Iacovides A, Fountoulakis K, Kaprinis S, Kaprinis G. The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;75:209–221. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vealey RS, Udry EM, Zimmerman V, Soliday J. Intrapersonal and situational predictors of coaching burnout. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1992;14:40–58. doi: 10.1123/jsep.14.1.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turnipseed DL. Anxiety and burnout in the health care work environment. Psychol Rep. 1998;82:627–642. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.2.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs SR, Dodd D. Student burnout as a function of personality, social support, and workload. J Coll Stud Dev. 2003;44:291–303. doi: 10.1353/csd.2003.0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richman JA, Flaherty JA. Gender differences in medical student distress: contributions of prior socialization and current role-related stress. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:777–787. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90201-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pyskoty CE, Richman JA, Flaherty JA. Psychosocial assets and mental health of minority medical students. Acad Med. 1990;65:581–585. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.IsHak W, et al. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. The clinical teacher 10, workload. J Coll Stud Dev. 2003;44:291–303. doi: 10.1353/csd.2003.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:61–67. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pew S Andragogy and pedagogy as foundational theory for student motivation in higher education. (2007). Student Motivation. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ864274.pdf. Accessed 16 Sep 2019.