Abstract

Besides sharing knowledge, values, and attitudes, the members of a profession share a way of understanding how to perceive life, also known as professional identity. The formation of this identity is related to the acquisition of multiple roles, responsibilities, and collaboration, defining their professional culture. The medical educator is a professional who is committed to student development, who is a leader in his field, and who is active in academic or clinical activities, demonstrating the commitment to the community. The objective of this study was to explore the professional culture through the perception of the medical educator identity. A qualitative method was implemented by applying a content analysis strategy. A sample of 39 medical educators participated in structured interviews. Answers transcription was analyzed unitizing assumptions, effects, enablers, and barriers through the professional culture model: individualism, balkanized, collegiality per project, and extended collaboration. The definition of the medical educator was associated with 44% to individualism, 31% balkanized, 13% collegiality per project, and 13% extended collaboration. Generally, contributions from Basic Science educators are more individual, and the projects in the university are part of the operation planned for the short and medium term. Clinical Science educators are used to working in medical specialty groups, and some of them are involved in strategical social projects that provide care for the community. A cultural change transitioning from a highly autonomous strategy toward meaningful collaborative projects can help physicians and health professionals to develop a shared vision of what it means to be a medical educator. The medical school should provide a sense of collegial community environment to set common goals and expectations with adequate resources, and leadership is the standard.

Keywords: Identity, Professional identity, Medical educator, Professional culture, Medical schools

Introduction

Professional identity has been widely discussed; however, its definition is inherently subjective because multiple individual and collective meanings integrate it. Professional identity dictates the roles and functions that an individual has in a work environment [1]. The individual must demonstrate mastery of skills but also adopt the social rules that indicate how he should behave and perceive himself [2]. This type of identity has an essential social conception since it allows the individual to position himself in a system where identification and differentiation are in a constant balance [3]. This type of identity is dynamic and under construction by the culture shared within different participants, interest groups, and contexts in the profession. Recently, medical educators have been immersed in a complex professional culture that makes them debate between priorities from multiple activities and roles.

Professional Culture

Professional culture is both the content and the dynamics within a profession [4]. The content refers to the beliefs, values, and habits, while the form refers to the models of association and membership. Hargreaves and Fullan describe the appropriation of this culture as part of the professional identity through four levels: individualism, balkanized, segregation, and extended collaboration [5].

The culture of individualism refers to a highly capable individual who works by himself because he feels independent, instead of being interdependent as a member of a larger whole; then, his obligations or responsibilities are due to their direct clients [4]. Conceptually, the construction of professional identity is consistent with the processes in which personality develops [6]. Erikson describes two processes: the biological, which represents the organization of the systems, and the psychic, which organizes the individual experience through the synthesis of the self [7]. From a cognitive development approach, Piaget identifies intelligence as the factor that shapes the physiological adaptation tied to cognitive evolution [8]. For Cruess, Cruess, Boudreau, Snell, and Steinert, the identity of the doctor is a representation of himself, formed through time, in which his characteristics, values, and norms of medicine have been internalized as a result of reasoning, acting, and feeling like a doctor [6].

Balkanized culture describes subgroups that share specialized training and have an intermittent interaction; their obligations are also for their direct leaders. The narration that an individual makes about himself, consequently, is a construction that comes from the symbolic interaction with the values of the profession [1]. Mead affirms that the identity is constructed as the person interacts with people and from there reinforcement of sociocultural patterns [9]. The process of assembling this identity should be on strong social, organizational, and relationships that provide context for the individual to evolve from the edge of a community of practice to a role of greater responsibility [5]. Becher describes communities in the academic environment as tribes with disciplinary cultures that have recognizable traits [10].

The term culture of segregation implies a negative perspective; therefore, a more generic term would be a culture of collegiality per project. This level refers to individuals who collaborate around a specific goal, with a manager who makes the team designation. The perception of identity as a stable and immovable construct has evolved into a dynamic conception where the individual has multiple facets or roles that are part of his own identity [6]. Hence, identity is described as multiple, dynamic, situational, and negotiable according to the activities or roles that the professional is taking part in.

Finally, the extended collaboration culture includes individuals who commit to the sustainability of the organization. This culture represents a tightly knit network in which individuals expect members of their group to show loyalty to the collective [4]. Wenger named these groups as a learning community and defines them as a project of profound social transformation, in which a group of people is involved in participatory education that transcends the classroom training [11]. For example, integration is observable in a group of surgeons exploring new treatment techniques or students who are defining their identity in a new school.

Medical Educator

Within the framework of professional identity, the case of teachers is of particular interest, because their activities include a constant balance among three areas: scholar, teaching students, and the connection with the professional environment of their discipline.

The medical educator is competent in patient care, research, management, and teaching-learning [6]. The medical educator is a professional who is committed to student development, who is a leader in his field, and who is active in academic or clinical activities demonstrating commitment to the community. Some models like the one from Steinert describe the concept in roles: education, curricular design, evaluation, educational leadership, innovation, and research [12]. Harden and Crosby proposed a framework of 12 areas of competence: information provider, model, facilitator, evaluator, curriculum and class planner, content creator, and producer of study guides [13]. The CanMedS model includes mental criteria that describe a good clinical teacher: expert doctor, communicator, collaborator, administrator, community leader, and academic [14]. Other models include the skills, knowledge, and attitudes that the educators must demonstrate to perform pedagogical skills.

Acting as a medical educator is different from being one, and the difference lies in the internalization of the values associated with their role, that is, the appropriation of their professional identity [15]. Adapting the model of Hargreaves and Fullan to medical education allows an interpretation that teachers have about their professional identity as members of the same educational project [3, 4].

The professional cultural approach of a medical educator at the individualism level refers to a person who performs tasks autonomously. A medical school, with this orientation, provides creativity and freedom for teaching, research, and clinical care, among other activities. However, institutional results may vary on performance and quality across users [13, 15]. Some authors consider that individualism impacts professional identity on physical and psychological isolation [4].

In the balkanized level of professional culture, the collaborative approach is seen as a united responsibility toward the group, for example, those who share the same specialty or teach the same subject. The medical school empowers these groups for the improvement of contents, the definition of evaluation methods, and the instructional design [4]. The impact on professional identity lies in the belonging within subgroups and the acceptance of common grounds from ways of thinking and teaching.

In the collegiality per project, the collaborative approach is temporal, strategic, and resource consuming. Teamwork projects arise from long-term medical school requirements, including program design, quality accreditations, or international partnerships, which demand multidisciplinary expertise and qualifications. The interaction of the members is regulated by time, costs, and leadership. The impact on professional identity is the construction of relationships with people from different organization levels and areas [4].

The extended collaboration cultural approach has a broader scope that goes beyond the medical school or the clinical care institutional facilities. The members of the group act with agency further than the predefined role. They participate as agents of change to improve the community or societal outcomes [12, 13]. Participant’s interaction arises freely, without restrictions on time or space. The identity of the medical educator is shaped by a shared vision that impacts professional identity with a sense of the willingness to participate as part of a learning community [4].

Every stage describes characteristics that accumulate through an incremental process. For example, a professor working in developing a new program (collegiality per project) must have already mastered the level of working with people from his medical specialty (balkanized) and must be excellent in delivering a class to students (individualism). This evolution process is presented graphically in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Professional culture model

The objective of this study was to explore the professional culture through the perception of the medical educator identity.

Materials and Methods

This is a pilot study that is part of a broader project aimed to understand the phenomenon of professional identity from the perspective of the medical educator [16]. A qualitative method was implemented using a content analysis strategy. Qualitative studies seek to understand on a personal level the motives and beliefs that are behind the actions of people, through the collection of words and behaviors [17]. The design focuses on analyzing the transcription of the interviews to identify and apply rules that divide each text into segments that can be treated at separate units [18]. One of the objectives of this strategy is unitizing assumptions, effects, enablers, and barriers in the text segments. This coding scheme is based on the themes that the researcher is searching for or uncovers as the text is being classified [19].

The instrument and methodology applied were early described by Steinert, who explored through open-ended questions the process of identity construction from medical educators [12]. Through this inquiry method, participants are encouraged to provide detail in their responses. The questions explored five areas: the definition of a medical educator, the process of becoming a medical educator, a moment when the medical educator felt the proudest, the required competencies, and what advice would the interviewed would give to a young person entering the field; however, for this study only the first one is reported. Steinert recommends using probes as follow-up questions; through these interviews, they were based on providing examples that could illustrate their claims.

The collected data was transcribed to an electronic format, which was aimed to organize and systematize the data for further analysis and interpretation [20]. The research team who was experienced in this type of design independently analyzed the transcription and used the professional culture model as a framework to identify categories, codes, and emergent themes. Once each researcher had completed the analysis, a consensus was reached about the data, and extracts of the transcription were gathered as examples of each level of professional culture [21].

Participants were selected by convenience sampling [18]. This method was recommended because of the advantage for the team research of this study of the ease of access and cost-effectiveness for conducting a pilot implementation that would provide information for formulating further studies [21]. The disadvantages are the possible bias on results because of the underrepresentation of the groups in the population and the lack of sensitivity to identify differences within those groups. The sample consisted of 39 medical educators from 1 private medical school, 59% women and 41% men. These professionals represented different disciplines, training backgrounds, and stages of the medical program. The participants belonged 39% to Basic Science and 61% to Clinical Sciences. All participants voluntarily consented their participation in the study. Information gathered remains confidential for this research only.

Results

The participants came from a variety of specialties: 21% Pediatrics, 18% Dentistry, and 8% Pharmacology, and the rest belonged to different medical disciplines, and the ages corresponded 21% to the 20–35 years group, 34% to 35–50, and 44% were over 50 years. The type of clinical settings in which they work had a balance of 51% private and 49% public sector.

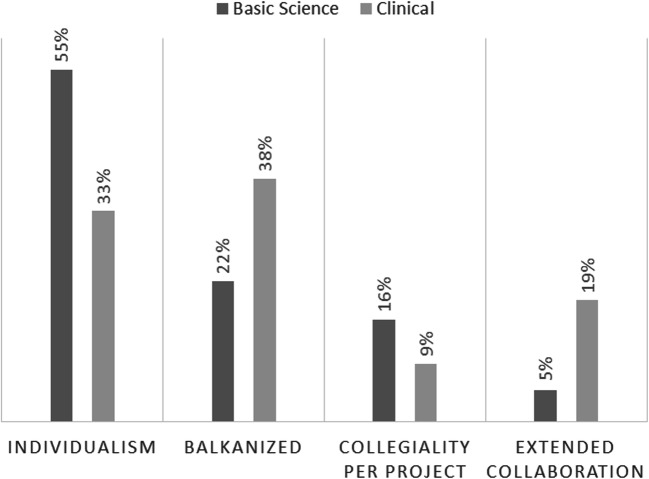

Table 1 summarizes the professional cultures derived from responses to the question about the meaning of being a medical educator. Categories indicated that participants’ answers about what it means to be a medical educator were 44% associated with the culture of individualism, 31% with balkanized culture, 13% with collegiality per project, and 13% to extended collaboration. Another analysis that was performed was the level of professional culture found across the different stages of the medical program. The professional culture of medical educators from the Basic Science and Clinical Sciences is presented in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Answers to the question of what it means to be a medical educator

| Professional culture | Incidence of category | Affiliation | Transcript extracts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individualism | 44% | Basic Science |

“Someone who facilitates learning” “Teacher in medical school” “Someone who has the required qualifications” |

| Clinical Science |

“A professional with the required credentials” “A professor in medical school” “A clinical doctor who teaches” “One who is learner-centric and prepared in his field” |

||

| Balkanized | 31% | Basic Science |

“Someone who shares medical knowledge and experience with others” “Facilitator of health sciences learning” |

| Clinical Science |

“A person who facilitates the teaching-learning process and feels responsible for their students” “A mentor who knows how to give feedback” “Any person that can teach and guide students in their training as a professional in medicine” “Teacher with participation in the medical field” |

||

| Collegiality per project | 13% | Basic Science |

“An individual who develops, implements, and evaluates the student training curriculum” “Someone who teaches by example and develops resources and experiences for learning” |

| Clinical Science |

“A person that goes the extra mile to be part of planning the teaching-learning experience to assure the desired outcome” “Wise competent mentor with role modeling skills” |

||

| Extended collaboration | 13% | Basic Science |

“Someone teaching, researching, and has scholarly contributions to public health” “One who teaches, learns from students, acts as a role model, develops resources, designs curriculum, facilitates faculty development workshops, and documents his educational research” |

| Clinical Science |

“A health professional committed to society, seeking with his experience to transmit knowledge and the patient’s well-being” “Teacher focused on contributing to the continuous improvement of the education of the medical student, to achieve a change in the care, diagnosis, and treatment of the patient that translates into an impact on global health” “A professional that commits to the students’ learning as well as for patient well-being” |

Fig. 2.

Basic Science and Clinical Science medical educators professional culture

Discussion

There was a higher concentration of individualism (44%). Participants argue that a medical educator was someone with the required credentials, someone that had a faculty appointment at a medical school, or someone who is a clinical doctor who teaches. They also made reference to the commitment toward the students’ learning. Although individuality is desirable in the development of highly capable professionals, this category does not include collaboration with other excellent medical educators [4]. Faculty working in isolation can have an impact on student learning and in the development of young teachers. Dolan found that the main issues are inadequate frequency and depth of communication, lack of recognition of instructor value to the institution, and lack of opportunities for skill development [2]. The concentration in Basic Science educators was higher (55%) from the clinical educators (33%) since classroom-based approaches require less coordination and interaction with peers than clinical settings.

The participants also showed a concentration toward a balkanized professional culture (31%). Participants described that a medical educator is someone who facilitates the teaching-learning process and shares experience with others who teach or train professionals in medicine. This approach has been found to offer important advantages like increased support, the opportunity for ongoing conversation about the teaching practice, and experience in learning how to collaborate to improve the educational program [22, 23]. Faculty with an orientation toward this culture has an impact on student learning improvement and on the development of younger teachers from medical educators’ perspectives [4]. However, balkanized culture could promote negative competition between small functional groups, departments, or specialties because of the lack of systemic vision from either academic or clinical settings from other areas. The balkanized culture was higher in Clinical Science (38%) than Basic Science educators (22%); this result is due to common spaces and practices within colleagues from the same medical specialty who share clinical experiences. For example, pediatricians have regular meetings to analyze patient cases.

The incidence of collegiality per project was the lowest score (13%). Participants provided examples of a medical educator being an individual who is involved in curriculum development to improve learning experiences. They also mentioned going the extra mile to assure the desired learning outcome or the graduate profile. This level of professional interaction resembles the cultural anthropology which is defined as an exact feeling of belonging to a group [24]. Basic Science educators were higher (16%) than clinical educators (9%). Basic Science educators reflected more participation in instructional design and program design than clinical educators because they feel more passionate about pedagogical strategies and curriculum contents. Clinicians were more concerned about practical experiences.

The incidence of extended collaboration was also a low figure (13%). Participants described a faculty member who is focused on contributing to the continuous improvement of medical education to impact patient care by diagnostic, treatment, and global health. They described a health professional who teaches, learns from students, acts as a role model, develops educational resources, participates in curriculum design, leads faculty development, and performs educational research. The identity of these medical educators is integrated by roles as clinicians and educators with multiple activities, including the commitment with the society [12, 14]. Clinical educators were higher (19%) than Basic Science educators (5%). Clinicians described themselves as part of the healthcare system and recognized the importance of their roles providing care to their community.

Generally, contributions from Basic Science educators are more individual, and the projects in the university are part of the operation planned for the short and medium term. Clinical Science educators are used to working in medical specialty groups, and some of them are involved in strategical social projects that provide care for the community.

Conclusions

Regarding professional culture, the results indicate that medical educators share beliefs and values toward individualism in medical education [12]. A reflection as medical schools is the focus given to the individual responsibilities of teachers. They receive individual feedback and economic incentives based on evidence such as publications, awards, and results from student satisfaction surveys. Although traditionally it has been seen as a way to improve the quality of education, it is more related to the prestige of the faculty themselves [25]. The community that works to achieve the educational project, as a whole, is responsible for helping medical students on becoming physicians [26]. Then, it is not the job of a single educator to do so.

A cultural change transitioning from a highly autonomous strategy toward meaningful collaborative projects can help physicians and health professionals to develop a shared vision of what it means to be a medical educator. The medical school should provide a sense of collegial community environment to set common goals, and expectations with adequate resources and leadership are the standard. The professional culture provides an atmosphere where peers share encouragement and appreciation of the crucial role they play as well as the experimentation of others. It can be done through orientation and feedback to clinicians in a systematic approach to providing concrete opportunities for collaboration and improvement [27]. Similarly, these activities would allow exploring possible mechanisms to attract new educators with the appropriate profiles and vocation to train the professionals of the future.

The perception that faculty members have on what it means to be a medical educator provides useful information on the status quo of the medical school. It contributes to design teacher training that nurtures collaboration through focused activities for the level of a professional culture that is shared, as well as motivating self-reflection for physicians to understand their strengths and weaknesses as a community. By incorporating it into cycles of continuous professional development, the practitioners can analyze how the professional culture impacts their teaching strategies or how they can plan a successful career in their institutions. The faculty development team can also adapt the current training programs to guarantee the minimum competencies required. The steering committee can gather insight on how to involve and promote their faculty into other roles, especially the ones that have shown higher impact con students, patients, and society.

Funding Information

No financial support was received for the development of this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Tecnologico de Monterrey.

Informed Consent

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Caballero K. Construcción y desarrollo de la identidad profesional del profesorado universitario [dissertation]. Granada, España: Universidad de Granada. 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/2200 Accessed 30 Sep 2019.

- 2.Ibarra H. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Adm Sci Q. 1990;44:764–727. doi: 10.2307/2667055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fullan M. Professional culture and educational change. School Psychology Review, 25: 496–5.

- 4.Hargreaves A, Fullan M. Understanding teacher development. London: Teacher College Press y Cassell; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, Young H. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25:369–364. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau D, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med 2014; 89,1446–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Munley PH. Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development and vocational behavior. J Couns Psychol. 1975;22:314–315. doi: 10.1037/h0076749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castilla MF. La teoría del desarrollo cognitivo de Piaget aplicada en la clase de primaria [dissertation]. Valladolid, Spain: Universidad de Valladolid. 2013. http://uvadoc.uva.es/handle/10324/5844 Accessed 30 Sep 2019.

- 9.Mead GH. Mind, self, and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becher T. Academic tribes and territories, intellectual enquiry and the cultures of disciplines. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open university Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization. 2000;7:225–221. doi: 10.1177/135050840072002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinert Y. Faculty development: on becoming a medical educator. Med Teach. 2012;34:74–72. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.596588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harden R, Crosby J. The good teacher is more than a lecturer: the twelve roles of the teacher. Teaching and Learning 2000; 22: 334–3.

- 14.Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van der Berg JW. The struggle to support the transition to medical educator. Med Educ. 2018;52:139–138. doi: 10.1111/medu.13505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López Cabrera MV, Olivares SL, Heredia, Y. Interpretacion de la identidad profesional del educador médico como miembro de un Proyecto educativo. Latin American Conference of Residency Education (LACRE) 2019; 2019 May 29-31; Santiago (Chile).

- 17.Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introduction to qualitative research methods: the search for meanings. New York: Wiley; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. New York: SAGE Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacherjee A. Social science research: principles, methods, and practices. Florida: USF Tampa Bay Open Access Textbooks Collection; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basic of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryman A. Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bullough RV, Young J, Birrel JR, Clark DC, Egan MW, Erickson L, Frankovich M, Brunetti J, Welling M. Teaching with a peer: a comparison of two models of student teaching. Teach Teach Educ. 2003;19:57–15. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00094-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolan V. The isolation of online adjunct faculty and its impact on their performance. Int Rev Res Open Dist Learn. 2011;12:63–14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walliman N. Research methods: the basics. London: Routledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sclafani S. Evaluating and rewarding the quality of teachers: international practices. Mexico: OECD Publishing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldie J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012;34:e641–e647. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.687476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berenson EA, Rice T. Beyond measurement and reward: methods of motivating quality improvement and accountability. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:2155–2130. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]