Abstract

Investigations into medical student study strategies have seen an increase in recent years, but we have also seen a move to more integrated medical curricula during this time. This manuscript endeavors to assess the changes in study plans and students’ reported study strategies that are associated with a move from a traditional stand-alone anatomy curriculum to an integrated, standardized curriculum. Previously validated study strategy surveys were given to medical students at the beginning of their anatomy course and again at the end of the course. These responses were then correlated with basic demographic information and outcomes in anatomy. Results indicate that this change in curriculum does correlate with changes to students’ study plans and reported study strategies. In particular, the plans for and use of web-based resources appear higher in the new curriculum while the use of self-quizzing and attendance appear lower, with potentially negative implications for understanding and long-term retention. Differences were also seen between genders and student ages. Finally, a few associations with outcomes are also noted for increased use of web-based resources and student confidence going into the exam.

Keywords: Dunning-Kruger effect, Integrated curriculum, Traditional curriculum, Web-based resources, Gender differences, Implicit curriculum

Introduction

Medical student study strategies remain a somewhat enigmatic topic for medical educators [1]. What is it that our students do outside of our classrooms to prepare for their assessments and future careers? What should we encourage them to do? Previous studies (detailed below) have looked at how medical students generally study, how they change their study plans throughout a course, and how they change their study strategies for different courses. However, as more and more medical schools in the USA are integrating their curricula in one way or another [2, 3], how do these curricular changes affect medical students’ study plans and strategies? This research adds to the literature by looking at medical students’ pre-course study plans and post-course reported study strategies in both a traditional stand-alone anatomy course and following a curricular overhaul into an integrated curricular model.

Medical and Professional Student Study Strategies

Crede and Kuncel [4] define study habits as “...study routines, including, but not restricted to, frequency of studying sessions, review of material, self-testing, rehearsal of learned material, and studying in a conducive environment.” It is the goal of these study habits or strategies to result in learning, though this may not always be the case. Furthermore, if learning does occur, it may be classified as superficial learning, which is concerned primarily with repeating the information as it was originally presented, or deep learning, involving engaging with the information and integrating the new information with previous experiences and understanding. Many students are believed to participate in both superficial and deep learning as the need arises based on course expectations, assessment, etc. [5]. This pattern of behavior is often referred to as strategic learning.

How students choose which study strategies to employ may depend on multiple factors, including both course and personal attributes. These factors include course content [6], course requirements [7–12], course logistics [13], personal interests [10], personal perceptions and attitudes towards the class [7, 14–16], and personal ideas on learning, motivation, and confidence [17, 1, 18, 19]. When examining medical student study strategies in anatomy, in particular, previous research has shown that students were most likely to participate in reading their notes/textbooks, memorizing information, recopying their notes, studying with classmates, and studying in the anatomy laboratory [20]. Unfortunately, Ward and Walker [20] go on to note that the majority of these study strategies do not lead to deep learning. Papinczak et al. [21] report that the majority of students begin medical school utilizing study strategies consistent with deep learning, but move away from those practices (towards more superficial or strategic strategies) during their first year of medical school due to the level and speed at which content is presented. This increase in superficial learning strategies was also seen in Ward’s later research [9], among others [22, 23]. However, Ward also noted that changing their approach to learning often correlated with lower mean grades [9]. Consistency in study strategies was further noted to positively correlate with outcomes by Husmann et al. [18], who found that changing more study strategies between courses correlated with lower grades. Both Ward [9] and Selvig et al. [14] also note that students who focused on superficial study strategies tended to have lower grades than their counterparts that also participated in deeper learning strategies.

Changes in Medical Curricula

Curricular change is by no means a new concept for the medical sciences. Over the past three hundred years, US medical schools have evolved through the apprenticeship model and the discipline-based model on into organ-system-based models, problem-based models, and clinical-presentation based models (see Papa and Harasym [24] for more information on each of these). In particular, medical educators think of Abraham Flexner and his integral report, published in 1910, that helped to instigate perhaps the most complete overhaul of medical curricula in US history by popularizing Johns Hopkins model of two basic science (pre-clerkship) years followed by two clinical (clerkship) years with an emphasis on scientific methodologies and clinical reasoning [25].

More recently, accrediting bodies have encouraged both horizontal (i.e., between disciplines) and vertical (i.e., between pre-clerkships and clerkships) integration of disciplines in medical curricula (e.g., Liaison Committee on Medical Education Data Collection Instrument 2020–2021, Standard 8.2 Narrative response b, accessed Sept. 12, 2019). At the same time, accrediting bodies have also required that students have unassigned time available in which to develop their self-directed learning skills (e.g., Liaison Committee on Medical Education Data Collection Instrument 2020–2021, Standard 6.3, Narrative response b, accessed Sept. 12, 2019). This requirement has then resulted in decreased hours available for class time.

When looking at anatomy in medical curricula specifically, a significant increase in the integration of anatomy curricula has occurred in the last decade. In their survey of gross anatomy instructors, McBride and colleagues [3] found that 26 of 55 (47.3%) respondents indicated that they had stand-alone anatomy courses. However, when McBride and Drake repeated this study a few years later [2], they found that only four of 66 (6%) respondents indicated that they still had a stand-alone anatomy course. When they looked at the number of hours devoted to anatomy, McBride and Drake [2] also found significantly decreased hours dedicated to both gross anatomy and histology.

Finally, one additional instigator for curricular change has been a call for more instruction on the implicit and hidden curricula in medical school [26]. Hafferty [27] defines the implicit curriculum as “an unscripted, predominantly ad hoc and highly interpersonal form of teaching and learning that takes place among and between faculty and students” while he defines the hidden curriculum as “a set of influences that function at the level of organizational structure and culture” (p. 404). These additional curricula have been implicated in the development of professionalism [28], specialty choice [29, 30], and cultural competency [31, 32], as well as the adoption of other norms and values of the profession [33, 34].

All of these curricular overhauls have been made in the attempt of creating more competent physicians and making the requirements therein more transparent. Yet despite all of these changes, curricula have yet to be found to be a significant influence on any of the US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1, 2, or 3 board scores [35] which are often used as markers of that competency. As such, we endeavor to evaluate the influence that changes in curriculum have made on the study plans that medical students report at the beginning of anatomy and the study strategies that they report using at the end of the course.

Methodology

Indiana University School of Medicine Set-up

The Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) has a nine-campus system set up all across the state of Indiana. The main medical campus resides in Indianapolis with eight regional medical campuses located in Bloomington, Evansville, Fort Wayne, Muncie, West Lafayette, Gary, South Bend, and Terre Haute. Prior to the fall of 2016, all campuses shared no less than 80% of the session level learning objectives and all gross anatomy courses began in the fall of the first year of medical school. In the fall of 2016, IUSM implemented a new statewide curriculum to better align with the accrediting guidelines listed above and to increase statewide standardization of their courses.

Legacy Curriculum—Human Gross Anatomy

Human Gross Anatomy was a first-year course that included both gross anatomy and clinically relevant embryology content. The course was divided into three to six blocks (depending on campus) and had both lecture and laboratory components. The course was assessed with one combined lecture exam and laboratory practical exam per block and one cumulative Gross Anatomy “shelf” final from the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME). The lecture exams were mostly multiple choice, some with a few short answer (1–3 sentences) questions. The laboratory practical exams were short answer (1–3 words), cadaver-based exams with predominantly identification questions and a few higher order (e.g., innervation or embryological origin) questions.

New Curriculum—Human Structure

In the fall of 2016, the previously silo-ed Human Gross Anatomy course was integrated with histology into a single Human Structure course to be completed during the first (fall) semester of medical school. While the course objectives dealing with the histology content were added to the course, all other course objectives stayed reasonably consistent. For example, the Human Gross Anatomy course included the objective “At the successful complete of our course, students will apply knowledge of normal embryonic development of the major organ systems to explain congenital defects and anomalies” while Human Structure included the objective “At the successful completion of our course, students will describe the embryology of organ systems and the developmental abnormalities that lead to common congenital defects.” All of the objectives for both courses were also mapped onto the institutional objectives to assure that the objectives were both consistent and standardized. Thus, while block exams in the previous Gross Anatomy course were developed and administered with local (campus) control, all exams in the new integrated Human Structure course are now developed and administered on a statewide level. Content within each block exam has remained 50% focused on lecture content and 50% focused on laboratory content. In addition, courses have continued to conclude with a cumulative National Board of Medical Examiner (NBME)-style “shelf” examination. However, in the new curriculum (NC), this cumulative NBME-style examination has also itself been designated a “high stakes” examination (i.e., students must pass this exam to pass the course). In addition, some changes were made to the NBME-style exam itself. For the previous stand-alone anatomy course, a traditional “shelf” examination was used that was written by the NBME and local instructors were not involved in the creation of the exam. The new integrated Human Structure course utilizes a customized NBME exam with questions that were chosen for the exam specifically by the statewide course management team.

The other major grading change instituted at this time was a new pass/fail system. In the legacy curriculum (LC), the passing cut-off was generally a merit-based cut-off of either 65 or 70% and grades were assigned on an Honors (top 10–20%), High Pass (top 25–40%), Pass, or Fail system. With the NC, the grading was changed to a strictly pass/fail grade and the cut-off for passing was established at 2 standard deviations below the statewide class mean. In both grading schema, no more than 5% of students (i.e., 18 students) failed across the state.

Following the completion of the first year in the NC, the Human Structure course continued to evolve with the following changes:

The histology laboratory was changed from an in-class laboratory using the virtual microscope (VM) to a self-directed learning model. (Note: the first week of laboratories were still completed in class to make sure that students understood the basic underlying principles and how to use the VM.)

The gross anatomy laboratory moved to a peer-teaching model with each student only attending half of the scheduled laboratory time.

Study Strategies Survey

The study strategies survey that was utilized for this study was previously developed by JB Barger (see Husmann et al., 2016 [18]) using methods established by Fowler (1995). As an overview, the survey included study strategy data, basic demographic data, and examination scores and final course grades. The survey included 37 questions, a majority of which were Likert scale questions while the demographic questions utilized individualized categorical options. The study strategy questions asked about resources the students might use to study throughout the course (e.g., reading the text, making tables, visiting websites) and general attitudes to the course (e.g., attendance, confidence going into the exam). For more information on the surveys and to view samples, see Husmann et al. (2016) [18].

Survey Administration

Students who were not on the same campus as the principal investigator (PH) were emailed a link to the survey administered through Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Students who had the principal investigator as an instructor were administered a paper copy of the survey by an outside administrator and the surveys were held by that administrator until after the course was completed in accordance with IRB protocol #1507250684. Both electronic and paper surveys included an informed consent statement complete with Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) release for students to sign. Students voluntarily completed the survey at the beginning and the end of either their Human Gross Anatomy course (AY 2015–2016) or their Human Structure course (AY 2016–2017 and AY 2017–2018). For this research, the previous curriculum will be referenced as the legacy curriculum (LC) while the new curriculum will be abbreviated as NC with NC1 referring specifically to the first year of the new curriculum (AY 2016–2017) and NC2 for the second year of the new curriculum (AY 2017–2018). The students’ grade data were then obtained from their instructors and linked to the survey responses. The data were then de-identified prior to sharing with the rest of the team and further analysis (detailed below).

Data Analysis

SPSS Statistics 24.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY) was utilized in compiling and formatting the data, as well as running statistical tests. Responses regarding study strategies were condensed into seven super-variables to minimize type 1 error associated with running numerous statistical tests. These new super-variables included:

Text-based resources: These four questions focused on the use of textbooks for the class, including diagrams, tables, or full-text use.

Lab-based resources: These two questions focused on the use of resources in or related to the laboratory component of the course, including dissectors and atlases.

Making study resources: These three questions asked if students personally made any resources with which to study, such as tables, drawings, or flashcards.

Web-based resources: These three questions focused on how students used the internet to assist in studying, including both the website for the course and other sites that students found on their own or at instructor recommendation.

Studying with others: These two questions focused on how often students studied with one or more of their classmates.

Self-quizzing: These three questions focused on how often students participated in self-quizzing specific behaviors, such as using review questions from the text, old examinations, or flashcards.

Attendance: These two questions focused on attendance for both lecture and laboratory components of the course.

Questions dealing with the number of hours of studying in the week preceding an examination and confidence walking into the examinations (post-course survey only) were also included in the survey but were kept separate from these larger categories.

Statistical comparisons were made between old and new curricula cohorts and between students in the upper and lower thirds of the classes based upon NBME examination scores. Multiple statistical tests were used to analyze the old versus new curriculum data, as well as to compare the top and bottom thirds of the students, including independent samples t tests and one-way ANOVAs. However, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs and Mann-Whitney U tests were utilized when parametric test assumptions (e.g., equality of variance and/or normality of data) were broken.

Results

Demographic data throughout the surveys (pre-course and post-course surveys for all three years) were compared and may be seen in Table 1. Chi-square analyses indicated that there were no statistically significant differences across these demographic categories among the three years of data collection.

Table 1.

Demographic information from all three years of data. Chi-square analyses indicated that there were no statistically significant differences among the three years

| Gross pre (n = 121) | Gross post (n = 103) | 2016 HS pre (n = 129) | 2016 HS post (n = 105) | 2017 HS pre (n = 139) | 2017 HS post (n = 118) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender: | ||||||

| - Male | 79 (65.3%) | 61 (59.2%) | 65 (50.4%) | 56 (53.3%) | 71 (51.1%) | 60 (50.8%) |

| - Female | 38 (31.4%) | 40 (38.8%) | 60 (46.5%) | 44 (41.9%) | 66 (47.5%) | 53 (44.9%) |

| Race | ||||||

|

- Asian- American |

19 (15.7%) | 13 (12.6%) | 18 (14.0%) | 11 (10.5%) | 17 (12.2%) | 10 (8.5%) |

|

- African- American |

6 (5.0%) | 11 (10.7%) | 9 (7.0%) | 7 (6.7%) | 7 (5.0%) | 5 (4.2%) |

| - Hispanic | 4 (3.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 17 (13.2%) | 9 (8.6%) | 5 (3.6%) | 5 (4.2%) |

| - White | 80 (66.1%) | 67 (65.0%) | 75 (58.1%) | 69 (65.7%) | 103 (74.1%) | 88 (74.6%) |

| - Other | 8 (6.6%) | 7 (6.8%) | 7 (5.4%) | 4 (3.8%) | 5 (3.6%) | 6 (5.1%) |

| Age | ||||||

| - < 22 | 5 (4.1%) | 1 (1.0%) | 9 (7.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 7 (5.0%) | 3 (2.5%) |

| - 22–23 | 69 (57.0%) | 57 (55.3%) | 83 (64.3%) | 66 (62.9%) | 99 (71.2%) | 77 (65.3%) |

| - 24–25 | 30 (24.8%) | 30 (29.1%) | 18 (14.0%) | 20 (19.0%) | 16 (11.5%) | 18 (15.3%) |

| - 26–27 | 7 (5.8%) | 5 (4.9%) | 9 (7.0%) | 4 (3.8%) | 10 (7.2%) | 10 (8.5%) |

| - 28+ | 6 (5.0%) | 7 (6.8%) | 7 (5.4%) | 8 (7.6%) | 5 (3.6%) | 6 (5.1%) |

| English first language | ||||||

| - Yes | 104 (86.0%) | 89 (86.4%) | 89 (69.0%) | 84 (80.0%) | 130 (93.5%) | 103 (87.3%) |

| - No | 13 (10.7%) | 11 (10.7%) | 18 (14.0%) | 15 (14.3%) | 7 (5.0%) | 11 (9.3%) |

Sample Bias

Response rates for all three years were as follows: AY 2015–2016—129, AY 2016–2017—105, AY 2017–2018—118. These numbers represent 35.44%, 28.85%, and 32.42%, respectively. When considering the mean final course averages and NBME examination scores between our sample and the larger class (including those students who did not complete the survey), no statistically significant results were found. The total class final grade average for NC1 (2016) was 76.4 (single sample t test: t = 1.755, p = 0.082), while the class final grade average for NC2 (2017) was 76.6 (single sample t test: t = 1.858, p = 0.066). This consistency was also seen with the NBME scores. The total class NBME average for NC1 was 72.2 (single sample t test: t = 1.936, p = 0.056) and for NC2 was 74.3 (single sample t test: t = 0.840, p = 0.403). While these results were not found to be statistically significant, it should be noted that the average scores of our sample did tend to be a bit higher than those of the class as a whole. Sample bias comparisons in the LC (legacy curriculum) were run using the NBME examinations only since each campus used their own (different) examinations except for the NBME cumulative final. This analysis also demonstrated consistency between the total class average (54.37) and our sample average (55.82, t = − 0.106, p = 0.916).

Differences in Survey Results Between Curricula

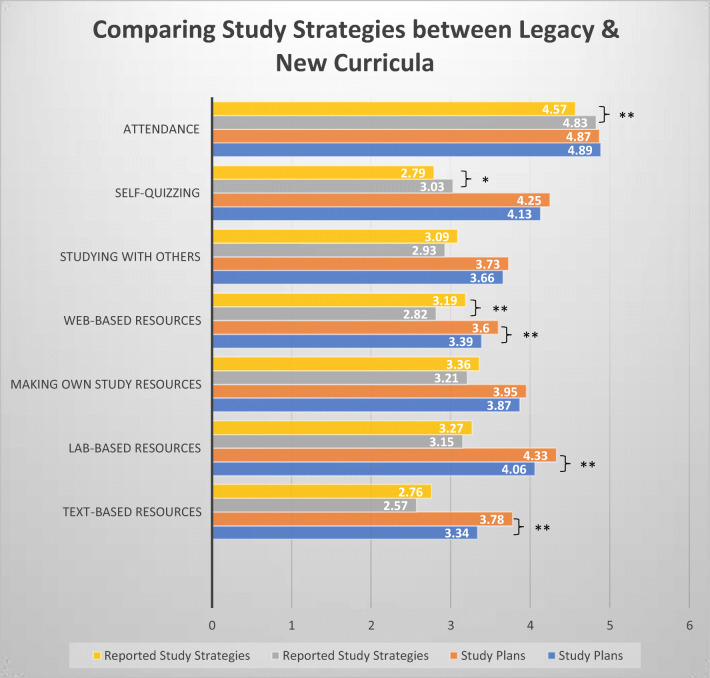

When examining students’ study plans between the LC and the NC, there were three categories in which statistically significant differences were found (Table 2 and Fig. 1). These categories were text-based resources, lab-based resources, and web-based resources. It should be noted that all three of these results focus on resources that were not made by students or faculty directly involved in the course and that students in the new curriculum were planning to use each of these resources more often than their counterparts in the previous curriculum had.

Table 2.

Independent samples t tests between study strategy supravariable results from the old curriculum and the new curriculum. Statistical significance cut-off p < 0.05

| Study plans (pre-course survey) | Reported study strategies (post-course results) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old curriculum mean | New curriculum mean | Sig. (2-tailed) | Old curriculum mean | New curriculum mean | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

| Text-based resources | 3.34 | 3.78 | 0.000* | 2.57 | 2.76 | 0.171 |

| Lab-based resources | 4.06 | 4.33 | 0.002* | 3.15 | 3.27 | 0.344 |

| Making own study resources | 3.87 | 3.95 | 0.420 | 3.21 | 3.36 | 0.263 |

| Web-based resources | 3.39 | 3.60 | 0.007* | 2.82 | 3.19 | 0.000* |

| Studying with others | 3.66 | 3.73 | 0.523 | 2.93 | 3.09 | 0.295 |

| Self-quizzing | 4.13 | 4.25 | 0.109 | 3.03 | 2.79 | 0.042* |

| Attendance | 4.89 | 4.87 | 0.714 | 4.83 | 4.57 | 0.000* |

* indicating statistical significance at p < 0.05

Fig. 1.

Comparisons of study plans and reported study strategies between the legacy curriculum and the new curriculum show multiple significant differences (double asterisks denote p < 0.01, a single asterisk denotes p < 0.05)

When attention is turned to reported student study strategies at the end of the course, there were also three categories in which statistically significant differences were found between students in the LC and those in the NC (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In this case, the three categories were web-based resources, self-quizzing, and attendance. In the new curriculum, students reported using web-based resources more often, while using self-quizzing and attending class less.

Relationships Between Study Strategies and Demographics

When study strategies in the NC were assessed across demographics, statistically significant differences were seen among gender, age, ethnic background, and English as second language status (Table 3). In particular, females were found to be significantly more likely to both plan to (pre-course survey) and report (post-course survey) making their own resources. The use of lab-based resources (e.g., atlases, dissectors) was found to positively correlate with age. At the same time, students who were less than twenty-two years old reported attending lecture less. Students of African-American backgrounds were found to more frequently report using texts and students who report English as a second language reported studying more with other classmates.

Table 3.

Non-parametric comparisons of study plans and strategy use across demographic variables in the new curriculum (NC) (ESL, English second language)

| Gender (Mann-Whitney U test) | Age (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) | Ethnic background (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) | ESL (Mann-Whitney U test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text-based plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1880.000 | 4.457 | 6.845 | 795.000 |

| p | 0.144 | 0.348 | 0.144 | 0.909 |

| n | 133 | 133 | 134 | 133 |

| Text-based strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 5106.000 | 5.761 | 11.369 | 2531.000 |

| p | 0.244 | 0.218 | 0.023* | 0.733 |

| n | 213 | 213 | 214 | 213 |

| Lab-based plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 2239.000 | 3.394 | 8.224 | 703.500 |

| p | 0.860 | 0.494 | 0.084 | 0.549 |

| n | 133 | 133 | 134 | 133 |

| Lab-based strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 5570.500 | 11.102 | 6.023 | 2541.500 |

| p | 0.995 | 0.025* | 0.197 | 0.704 |

| n | 212 | 213 | 213 | 213 |

| Making own resources plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 2729.500 | 4.228 | 5.676 | 661.000 |

| p | 0.016* | 0.376 | 0.225 | 0.385 |

| n | 133 | 132 | 133 | 132 |

| Making own resources Strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 7471.500 | 4.539 | 3.861 | 2570.500 |

| p | < 0.0001** | 0.338 | 0.425 | 0.633 |

| n | 213 | 213 | 214 | 213 |

| Web-based plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 2153.500 | 1.533 | 2.749 | 785.000 |

| p | 0.828 | 0.821 | 0.601 | 0.969 |

| n | 133 | 133 | 134 | 133 |

| Web-based strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 5411.500 | 1.968 | 4.505 | 2233.500 |

| p | 0.723 | 0.742 | 0.342 | 0.499 |

| n | 212 | 213 | 213 | 213 |

| Study with others plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 2340.500 | 0.949 | 4.645 | 884.500 |

| p | 0.523 | 0.917 | 0.326 | 0.389 |

| n | 133 | 132 | 133 | 132 |

| Study with others strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 5632.500 | 4.237 | 6.087 | 3046.000 |

| p | 0.884 | 0.375 | 0.193 | 0.030* |

| n | 212 | 212 | 213 | 212 |

| Self-Quizzing Plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 2238.000 | 3.011 | 4.124 | 776.000 |

| p | 0.736 | 0.556 | 0.389 | 0.984 |

| n | 132 | 132 | 133 | 132 |

| Self-quizzing strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 6231.500 | 4.260 | 6.897 | 2508.500 |

| p | 0.133 | 0.372 | 0.141 | 0.791 |

| n | 212 | 213 | 213 | 213 |

| Attendance | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 5914.000 | 20.371 | 4.124 | 2056.000 |

| p | 0.479 | < 0.001** | 0.389 | 0.161 |

| n | 213 | 213 | 133 | 213 |

* indicating statistical significance at p < 0.05

Similar tests with students in the LC further support a few of these trends (Table 4). In the LC, females were also found to be significantly more likely to both plan to and report making their own resources. The use of lab-based resources was also found to positively correlate with age in the LC. When the course outcomes were compared, females were found to have significantly lower scores on the NBME in both the LC and the NC (t = 3.884, p < 0.001 and t = 2.402, p = 0.017, respectively). No other demographic categories were related to statistically significant differences in course outcomes.

Table 4.

Non-parametric comparisons of study plans and strategy use across demographic variables in the legacy curriculum (LC) (ESL, English second language)

| Gender (Mann-Whitney U test) | Age (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) | Ethnic background (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA) | ESL (Mann-Whitney U test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text-based plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1241.000 | 4.487 | 3.154 | 494.000 |

| p | 0.625 | 0.344 | 0.532 | 0.852 |

| n | 104 | 104 | 104 | 104 |

| Text-based strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 782.000 | 4.454 | 1.817 | 392.500 |

| p | 0.408 | 0.348 | 0.874 | 0.848 |

| n | 86 | 85 | 85 | 85 |

| Lab-based plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1152.000 | 3.699 | 3.205 | 635.000 |

| p | 0.618 | 0.448 | 0.524 | 0.469 |

| n | 106 | 106 | 106 | 106 |

| Lab-based strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 996.000 | 12.072 | 7.486 | 420.500 |

| p | 0.601 | 0.017* | 0.187 | 0.969 |

| n | 89 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| Making own resources plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1584.000 | 0.961 | 4.739 | 457.500 |

| p | 0.009** | 0.916 | 0.315 | 0.307 |

| n | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Making own resources strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1193.500 | 1.498 | 3.305 | 354.000 |

| p | 0.042* | 0.827 | 0.653 | 0.343 |

| n | 90 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Web-based plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1313.500 | 5.608 | 8.533 | 698.000 |

| p | 0.381 | 0.230 | 0.074 | 0.154 |

| n | 105 | 105 | 105 | 105 |

| Web-based strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1071.500 | 2.344 | 3.397 | 325.000 |

| p | 0.206 | 0.673 | 0.639 | 0.388 |

| n | 89 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| Study with others plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1337.500 | 6.467 | 2.619 | 591.000 |

| p | 0.145 | 0.167 | 0.624 | 0.357 |

| n | 103 | 103 | 103 | 103 |

| Study with others strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1145.500 | 2.373 | 5.677 | 319.000 |

| p | 0.104 | 0.668 | 0.339 | 0.166 |

| n | 90 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Self-quizzing plans | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1452.500 | 1.639 | 1.633 | 485.000 |

| p | 0.115 | 0.802 | 0.803 | 0.422 |

| n | 106 | 106 | 106 | 106 |

| Self-quizzing strategy use | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 1164.000 | 3.042 | 2.327 | 354.000 |

| p | 0.075 | 0.551 | 0.802 | 0.346 |

| n | 90 | 89 | 89 | 89 |

| Attendance | ||||

| U/ANOVA | 926.500 | 1.181 | 4.801 | 400.000 |

| p | 0.769 | 0.881 | 0.187 | 0.619 |

| n | 90 | 89 | 82 | 89 |

* indicating statistical significance at p < 0.05

Relationships Between Study Strategies and Class Standing (Top and Bottom Thirds)

For the NC, study plans and strategies were compared between students with scores in the top and bottom thirds of the class on the NBME. This analysis demonstrated that the only statistically significant differences were the categories of (1) reported use of web-based resources and (2) generally felt that I had studied enough going into an exam (Table 5). For both variables, students with NBME scores in the bottom third of the class generally reported higher scores than students in the top third of the class. Unfortunately, this same comparison could not be done in the LC as only two students that participated in this study had NBME scores in the bottom third of the class.

Table 5.

Mann-Whitney U comparisons of study plans and strategy use between students in the top and bottom thirds of the class

| Category | Mann-Whitney U | p value | Top third n | Bottom third n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Text-based plans | 446.000 | 0.075 | 68 | 18 |

| Text-based strategy use | 1136.000 | 0.448 | 115 | 22 |

| Lab-based plans | 573.500 | 0.674 | 68 | 18 |

| Lab-based strategy use | 1177.000 | 0.736 | 112 | 22 |

| Making own resources plans | 559.000 | 0.632 | 67 | 18 |

| Making own resources strategy use | 1135.000 | 0.799 | 112 | 21 |

| Web-based plans | 584.000 | 0.763 | 68 | 18 |

| Web-based strategy use | 827.500 | 0.014* | 112 | 22 |

| Study with others plans | 536.000 | 0.464 | 67 | 18 |

| Study with others strategy use | 1087.000 | 0.622 | 111 | 21 |

| Self-quizzing plans | 530.500 | 0.428 | 67 | 18 |

| Self-quizzing strategy use | 1053.500 | 0.281 | 112 | 22 |

| Attendance | 1150.000 | 0.860 | 112 | 21 |

| Hours reported studying | 1105.500 | 0.522 | 112 | 21 |

| Student felt that they had studied enough | 467.500 | < 0.001** | 112 | 17 |

* indicating statistical significance at p < 0.05

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that there are significant differences in students’ study strategies between the gross anatomy stand-alone course in our previous curriculum and the more integrated Human Structure course in our new curriculum. At the beginning of the semester, our students now plan to use more textbooks, lab resources, and websites. At the end of the semester, our students report using more websites and spending less time attending class and quizzing themselves. We also found some study strategies that are significantly associated with demographics (e.g., females more likely to make their own resources and older students more likely to utilize lab-based resources). Finally, higher reports of using web-based resources and feeling as though they had studied enough going into the exams were associated with NBME scores in the bottom third of the class.

Looking specifically at the differences in study plans at the beginning of the semester, the results demonstrated that students in the NC were more likely to plan to use references that were not created by their instructors than had previously been seen with the LC. This trend may be due to the change in the writing of the exams. Since the local instructors were no longer writing the exams on their own, it is no longer as important to focus on the resources created by those instructors. These results are also consistent with previous research in study strategies related to course size and duration and may relate to rapport with the instructors in charge of the course. Previous research that evaluated medical student study strategies in anatomy related to course duration and class size, found that students in large cohorts with an anatomy course of one semester were more likely to employ outside resources [13]. Given the level of standardization across the state for the NC, students may have felt less connected to the faculty that were actually in charge of the course, since this was now done at the statewide level. These results may also relate to the commercialization of education, which has certainly been discussed at length for higher education more generally (e.g., [36–38]). In particular, with the greater focus on USMLE Step 1 scores, many students are focusing on resources associated with that exam since it may now constitute the only “grade” or quantitative value that they receive for their first two years of medical school (though this may soon change).

When evaluating the differences in reported study strategies at the end of the course, students generally report using more web-based study tools, less self-quizzing practices, and attending class less. When viewing online study tools, one question that must be addressed is the quality of these tools. While our students did not indicate precisely which online tools they were using, Barry and colleagues [39] found that one of the most common online resources used by their second-year medical students was YouTube. However, Raikos and Waidyasekara [40] had previously found that the quality of many YouTube videos (specifically for heart anatomy) was questionable. Thus, previous literature has called for instructors to be conscious of the quality of YouTube videos that their students are using and perhaps even consider producing YouTube videos to align with the class [41, 40, 39]. Raikos and Waidyasekara even provide a rubric for instructors to use to that effect. Yet, some studies have also found a fair number of high-quality resources available for students. Specifically, Choi and colleagues [42] found good quality resources were available online for surgical trainees to brush up on their anatomy. However, it must be acknowledged that this study is now more than a decade old. Furthermore, the use of web-based study tools was also associated with NBME scores in the bottom third of the class, which may further suggest that some of the online resources being used by students may not be of the highest quality or well-aligned with the course. It must also be acknowledged that students may get distracted by other websites if they regularly employ online resources to help study.

In addition, there is also some concern innate in the result that our students are reporting less self-quizzing. Self-quizzing as a form of retrieval practice has now been well established as a beneficial practice for learning in general, as well as in anatomy specifically. The labs of Roediger and Karpicke have investigated this phenomenon extensively with science content (e.g., physics). They have found that the act of practicing retrieval increases the long-term retention of the material that was tested and related (non-tested) material better than simply re-reading, re-studying, or even creating concept maps of the information [43–48]. Dobson has further investigated these effects with anatomy content with similar conclusions [49, 50]. Thus, if our students are not reporting using these self-quizzing practices, these studies by Dobson, Roediger, and Karpicke suggest that it may have profound and concerning implications, particularly for the long-term retention of this material in our students.

Finally, there are also some concerns around students attending class less. Attendance has been shown to correlate with course outcomes in undergraduate education [51]. However, the results have been significantly more mixed at the medical education level. Laird-Fick and colleagues [52] found some relationship between attendance and outcomes in their large-group flipped class setting, yet this is likely a much more active learning environment than many large classrooms. A relationship between attendance and board exam scores was also noted by Fogleman and Cleghorn [53]. However, the landscape of medical education has changed significantly since 1983. Eisen and colleagues [54] did not find a relationship between attendance and academic performance in a second-year dermatology course. Likewise, Azab and colleagues [55] did not note a significant relationship between class attendance and outcomes in their study with second-year dental students. With these mixed results at the professional school level, many questions remain. While the knowledge-based outcomes examined in the above studies do not seem to indicate a strong relationship with attendance, many researchers also suggest that anatomy courses may be important in the implicit and/or hidden curricula of medical schools [56–58]. Either or both of these additional curricula are also substantially at risk as students’ attendance continues to decline, which could have profound implications for the professionalism, interpersonal skills, and/or professional values of medical school graduates.

When considering the demographic variables that were significantly associated with study strategies, the increased reporting of females creating their own study resources was interesting to note. This would seem to suggest a great deal of active engagement with the content, which should be beneficial for understanding and retention [59, 20]. Yet, the comparison of outcomes data does not support this interpretation. Potential explanations for these results include the amount of time necessary to create one’s own resources or possibly focusing on material that was not as high yield. However, further investigation is required to parse out these details. While these trends have not been researched extensively in medical students, previous research with undergraduates had also found differences in study strategies between males and females [10, 16], though the exact strategies used vary. Vermunt [10] found that females were more likely to participate in cooperative learning (e.g., studying with other students) while Delaney and colleagues [16] report that females were more likely to attend class than their male counterparts. Both of these results might suggest that female students are more likely to rely on their colleagues, but this seems to counter our results in which females more consistently report making their own resources (as opposed to relying on someone else), and gender was not associated with differences in attendance in our data. However, Ward [9] had previously noted that female medical students demonstrated higher fear of failure rates than males, so all of these trends may illustrate ways in which females attempt to overcome that fear. In addition, Smith and Mathias [5] found that female medical students were more likely to utilize strategic approaches to their studies while males were more likely to utilize deep approaches. These results may also be consistent with female attempts to overcome a fear of failure as they focus on the strategies necessary for the assessments. Unfortunately what is consistent with our data and previous research, is that female medical students tend to have lower course grades in anatomy than males [18], so more work is needed to help improve these outcomes.

Vermunt [10] and Edmunds and Richardson [19] also found differences in study strategies associated with age. In particular, they note that older students tend to employ study strategies consistent with deep learning. These results may be seen as consistent with the results presented here when considering that increased use of lab-based resources may indicate higher levels of integration between lecture and lab, which may suggest deeper learning.

Study strategy comparisons between students with NBME scores in the top and bottom thirds of the class, however, appear much more straightforward. As noted above, increased use of web-based resources can result in resources of questionable quality and may also result in increased distractions for students, so their association with lower NBME scores is not overly surprising. The correlation between lower outcomes and higher scores on feeling as though they have studied enough for the exam, on the other hand, is a classic demonstration of what has come to be known as the Dunning-Kruger effect [60]. In this work, Kruger and Dunning demonstrate that students who perform poorly tend to be overconfident going into their exams while students that tend to perform well are more likely to be cautious in their confidence levels. Thus, a negative correlation exists between exam scores and confidence going into the exam. This effect has also been seen in prior data specifically with anatomy [59].

Limitations

As with all research, there are several limitations to this study. One limitation is the use of self-reported data. Allowing students to self-report how they study may result in inaccuracies in the information as students misremember, misrepresent, or otherwise alter their reported techniques, particularly when they know that the information will eventually be seen by their instructor. Another limitation is the incomplete sample. Our response rates for this research were not ideal; however, they are not uncommon given that we were asking medical students to complete additional work in completing the surveys. Additional research with higher response rates would be incredibly beneficial. Finally, the move to the new curriculum at IUSM included changes in the organization, assessment, and statewide standardization, all at the same time. Thus, it is difficult to parse out which changes most directly affected the students. Unfortunately, these decisions are well beyond our control as instructors and therefore were unable to be controlled. This is likely a common situation in most schools as assessments need to align with the course organization. We do recognize, however, that the additional variable of statewide standardization may limit the generalizability of these results to medical schools, like IUSM, who have students on multiple campuses.

Conclusions

This research endeavored to compare study plans and strategies between our previous traditional curriculum with a stand-alone gross anatomy course and a new standardized, integrated curriculum. Our results demonstrate that in the new integrated curriculum, students are more likely to plan to use outside resources that were not created specifically for this course (e.g., websites, textbooks). In addition, by the end of the semester, students in this new curriculum are more likely to utilize web-based study resources, less self-quizzing, and decreased class attendance. These new study plans likely relate to the increased reliance of residencies on Step I scores and the statewide standardization of the course, while the new trends in reported study strategies may also have profound implications for long-term retention [43–50] and implicit and/or hidden curricula [56–58]. Results also demonstrate consistent differences in study strategies with age and gender as well as a few differences between students in the top and bottom thirds of the class. In particular, we show that students should be cautious in using web-based resources without discernment as increased use of online resources was associated with NBME scores in the bottom third of the class and previous research has questioned the quality of web-based resources [40]. Thus, evaluating the quality of the resource and its alignment with the class must be considered. Furthermore, self-monitoring to confirm attention to course content (and not other online distractions) must be maintained. In addition, we have also shown that the negative correlation between exam scores and confidence going into the exam (i.e., the Dunning-Kruger effect) is still alive and well with our medical student population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the students who participated in the surveys that led to this work. We would also like to thank Jackie Cullison for her help in administering the surveys to students on the Bloomington campus.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

All research was completed in alignment with accepted ethics of Human Subjects Research (Indiana University IRB protocol #1507250684A001).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dunn-Lewis C, Finn K, FitzPatrick K. Student expected achievement in anatomy and physiology associated with use and reported helpfulness of learning and studying strategies. HAPS-Educator. 2016;20(4):27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McBride JM, Drake RL. National survey on anatomical sciences in medical education. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(1):7–14. doi: 10.1002/ase.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake RL, McBride JM, Pawlina W. An update on the status of anatomical sciences education in United States medical schools. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7:321–325. doi: 10.1002/ase.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crede M, Kuncel NR. Study habits, skills, and attitudes: the third pillar supporting collegiate academic performance. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(6):425–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith CF, Mathias H. An investigation into medical students’ approaches to anatomy learning in a systems-based prosection course. Clin Anat. 2007;20:843–848. doi: 10.1002/ca.20530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldman RD, Hudson DJ. A multivariate analysis of academic abilities and strategies for successful and unsuccessful college students in different major fields. J Educ Psychol. 1973;65(3):364–370. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eley MG. Differential adoption of study approaches within individual students. High Educ. 1992;23:231–254. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aharony N. The use of deep and surface learning strategies among students learning English as a foreign language in an Internet environment. Br J Educ Psychol. 2006;76:851–866. doi: 10.1348/000709905X79158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward PJ. First year medical students’ approaches to study and their outcomes in a gross anatomy course. Clin Anat. 2011;24:120–127. doi: 10.1002/ca.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermunt JD. Relations between student learning patterns and personal and contextual factors and academic performance. High Educ. 2005;49(3):205–234. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanger-Hall KF. Multiple-choice exams: an obstacle for higher-level thinking in introductory science classes. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11:294–306. doi: 10.1187/cbe.11-11-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mji A. Conceptions of learning: views of undergraduate mathematics students. Psychol Rep. 1998;83:982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husmann PR. Medical student study strategies in relation to class size and course length. HAPS-Educator. 2018;22(3):187–198. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvig D, Holaday LW, Purkiss J, Hortsch M. Correlating students’ educational background, study habits, and resource usage with learning success in medical histology. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;8:1–11. doi: 10.1002/ase.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knight JK, Smith MK. Different but equal? How nonmajors and majors approach and learn genetics. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2010;9:34–44. doi: 10.1187/cbe.09-07-0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaney L, Harmon C, Ryan M. The role of noncognitive traits in undergraduate study behaviors. Econ Educ Rev. 2013;32:181–195. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pizzimenti MA, Axelson RD. Assessing student engagement and self-regulated learning in a medical gross anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;8:104–110. doi: 10.1002/ase.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Husmann PR, Barger JB, Schutte AF. Study skills in anatomy and physiology: is there a difference. Anat Sci Educ. 2016;9:18–27. doi: 10.1002/ase.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edmunds R, Richardson JTE. Conceptions of learning, approaches to studying and personal development in UK higher education. Br J Educ Psychol. 2009;79:295–309. doi: 10.1348/000709908X368866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward PJ, Walker JJ. The influences of study methods and knowledge processing on academic success and long-term recall of anatomy learning by first-year veterinary students. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1:68–74. doi: 10.1002/ase.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papinczak T, Young I, Groves M, Haynes M. Effects of a metacognitive intervention on student’s approaches to learning and self-efficacy in a first year medical course. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2008;13:213–232. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martenson DF. Students’ approaches to studying in four medical schools. Med Educ. 1986;20:532–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tooth D, Tonge K, McManus IC. Anxiety and study methods in preclinical students: causal relation to examination performance. Med Educ. 1989;23:416–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papa FJ, Harasym PH. Medical curriculum reform in North America, 1765 to the present: a cognitive science perspective. Acad Med. 1999;74(2):154–164. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199902000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludmerer KM. Abraham Flexner and medical education. Perspect Biol Med. 2011;54(1):8–16. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2011.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner Report. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1339–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilton SR, Slotnick HB. Proto-professionalism: how professionalisation occurs across the continuum of medical education. Med Educ. 2004;39(1):58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gofton W, Regehr G. What we don’t know we are teaching: unveiling the hidden curriculum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;449:20–27. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000224024.96034.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahood SC. Medical education: beware the hidden curriculum. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(9):983–985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wachtler C, Troein M. A hidden curriculum: mapping cultural competency in a medical programme. Med Educ. 2003;37:861–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turbes S, Krebs E, Axtell S. The hidden curriculum in multicultural medical education: the role of case examples. Acad Med. 2002;77(3):209–216. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200203000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern DT. Practicing what we preach? An analysis of the curriculum of values in medical education. Am J Med. 1998;104(6):569–575. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaufberg E, Batalden M, Sands R, Bell SK. The hidden curriculum: what can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Acad Med. 2010;85(11):1709–1716. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f57899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hecker K, Violato C. Medical school curricula: do curricular approaches affect competence in medicine? Fam Med. 2009;41(6):420–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang N, Carpenter V. A case study of emerging challenges and reflections on internationalization of higher education. Int Educ Stud. 2014;7(9):56–68. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altbach PG. Higher education and the WTO: globalization run amok. Int High Educ. 2015;23. 10.6017/ihe.2001.23.6593.

- 38.Natale SM, Doran C. Marketization of education: an ethical dilemma. J Bus Ethics. 2012;105:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barry DS, Marzouk F, Kyrylo C-O, Bennett D, Tierney P, O’Keeffe GW. Anatomy education for the YouTube generation. Anat Sci Educ. 2015;9:90–96. doi: 10.1002/ase.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raikos A, Waidyasekara P. How useful is YouTube in learning heart anatomy? Anat Sci Educ. 2013;7:12–18. doi: 10.1002/ase.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaffar AA. YouTube: an emerging tool in anatomy education. Anat Sci Educ. 2012;5:158–164. doi: 10.1002/ase.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi A-RA, Tamblyn R, Stringer MD. Electronic resources for surgical anatomy. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:1082–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan JCK, McDermott KB, Roediger HL., III Retrieval-induced facilitation: initially nontested material can benefit from prior testing of related material. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2006;135(4):553–571. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karpicke JD, Roediger HL., III The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science. 2008;319(5865):966–968. doi: 10.1126/science.1152408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karpicke JD, Butler AC, Roediger HL., III Metacognitive strategies in student learning: do students practise retrieval when they study on their own. Memory. 2009;17(4):471–479. doi: 10.1080/09658210802647009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karpicke JD, Blunt JR. Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science. 2011;331:772–775. doi: 10.1126/science.1199327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roediger HL, III, Karpicke JD. Test-enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(3):249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roediger HL, III, Butler AC. The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(1):20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dobson JL, Perez J, Linderholm T. Distributed retrieval practice promotes superior recall of anatomy information. Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10:339–347. doi: 10.1002/ase.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dobson JL, Linderholm T. Self-testing promotes superior retention of anatomy and physiology information. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2015;20:149–161. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crede M, Roch SG, Kieszczynka UM. Class attendance in college: a meta-analytic review of the relationship of class attendance with grades and student characteristics. Rev Educ Res. 2010;80(2):272–295. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laird-Fick HS, Solomon DJ, Parker CJ, Wang L. Attendance, engagement and performance in a medical school curriculum: early findings from competency-based progress testing in a new medical school curriculum. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5283. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fogleman BS, Cleghorn GD. Relationship between class attendance and NBME part I examination. J Med Educ. 1983;58(10):904. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198311000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eisen DB, Schupp CW, Isseroff RR, Ibrahimi OA, Ledo L, Armstrong AW. Does class attendance matter? Results from a second-year medical school dermatology cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(7):807–816. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Azab E, Saksena Y, Alghanem T, Midle JB, Molgaard K, Albright S, et al. Relationship among dental students’ class lecture attendance, use of online resources, and performance. J Dent Educ. 2015;80(4):452–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lachman N, Pawlina W. Integrating professionalism in early medical education: the theory and application of reflective practice in the anatomy curriculum. Clin Anat. 2006;19:456–460. doi: 10.1002/ca.20344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Escobar-Poni B, Poni ES. The role of gross anatomy in promoting professionalism: a neglected opportunity! Clin Anat. 2006;19:461–467. doi: 10.1002/ca.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearson WG, Jr, Hoagland TM. Measuring change in professionalism attitudes during the gross anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:12–16. doi: 10.1002/ase.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eleazer CD, Kelso RS. Influence of study approaches and course design on academic success in the undergraduate anatomy laboratory. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11:496–509. doi: 10.1002/ase.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]