Abstract

Recent efforts to enrich the medical education experience recommended interinstitutional and collaborative efforts. Within this context, the author describes a model for school-specific augmented medical education. The evidence-backed conceptual model is composed of six foundational elements, which include the following: technology-enriched learning environments, analytics to drive instructional interventions, cognitive neuroscience and educational psychology research (the Science of Learning), self-regulated learning strategies, competency-based approaches, and blended learning instructional design. Harnessing the creativity of our leadership, medical educators, and learners is fundamental to improving the learning experience for all. This model could be used to meaningfully guide implementation processes.

Keywords: Medical education, Blended learning, Educational technologies, Cognitive neuroscience, Instructional design, Faculty development

Blended learning designs use appropriate technologies to help create meaningful face-to-face sessions that promote a learner-centered atmosphere where active learning is favored, and measurable learning objectives define the environment [1–4]. In such an environment, the role of the educator changes from a “teller” of information at the front of the room to an “academic coach” who carefully orchestrates individualized practice sessions that prepare learners for their gameday assessments. Although educational technology allows us the means to provide content in different ways, it is not the primary driver. How we use appropriate technologies and harness the creative energy of our faculty members and students to improve the learning experience for everyone is what matters. In a learner-centered environment, interactions are different from lecture-based sessions—medical educators are responsible for ensuring those interactions are deeper, contextually-relevant, and more meaningful.

Le and Prober described how customized digital solutions, curricular redundancies, and inconsistencies impact fiscal resources for medical education students, faculty members, and institutions [5]. And in response, they proposed a shared curricular ecosystem model, where medical students would participate in common competency-based learning experiences, regardless of institutional location. They also indicated that such a shared curricular ecosystem would potentially enrich the educational experiences for students, while “augmenting the unique characteristics of each medical school” [5; p. 105]. Their pioneering proposal launches new possibilities for exploring school-specific augmented medical education experiences and examining how medical school programs could evolve under such a paradigm shift.

Technology-enriched learning incorporates appropriate interactions to create dynamic and personalized environments where learners practice self-regulated learning strategies [6]. Within the shared curricular ecosystem proposed by Le and Prober, school-specific medical educators could construct contextually relevant and innovative digital learning ecosystems by carefully blending appropriate instructional design features with pedagogical practices grounded in cognitive neuroscience research [5]. Thus, the primary goal of this article is to describe a model for school-specific augmented medical education.

Description of Augmented Medical Education

Digital learning environments, competency-based approaches, and frameworks utilizing entrustable professional activities are guiding recent undergraduate medical education enhancement initiatives [7–9]. And, preclinical medical education reform initiatives promote experiential learning opportunities that map to national physician competencies [10, 11]. Under this context of medical education reform, what does school-specific augmented medical education look like and how might it function?

Le and Prober proposed a shared curricular ecosystem with common standards for implementation at-scale [5]. The shared curricular ecosystem could potentially remove educational redundancies, improve curriculum alignment, and make better use of limited human capital (faculty effort) and fiscal resources [5]. Within a shared ecosystem, medical students could consume content on-demand via an iTunes®-like model. Students could choose relevant content at the topic-level from virtually any institution and any participating faculty member. Faculty members could receive royalties (a compensation percentage) for every lecture a learner downloads. This might serve as a motivator since the best content producers would likely be accessed more than others, which would improve quality for the entire shared ecosystem across time. At the institutional level, resource allocations would change dramatically. Physical spaces, digital platforms, and faculty effort are three high-level arenas where financial resources could be modified.

By minimizing faculty effort toward delivering redundant (and uneven) lectures, medical school programs could offer site-specific opportunities that align better with their unique characteristics. School-specific programs and faculty members could focus less effort on fundamental knowledge building and more on skills/behaviors development, clinical applications, and experiential opportunities. Optimal site-specific curriculum delivery with high-impact student interactions is the hallmark of this school-specific augmented medical education model.

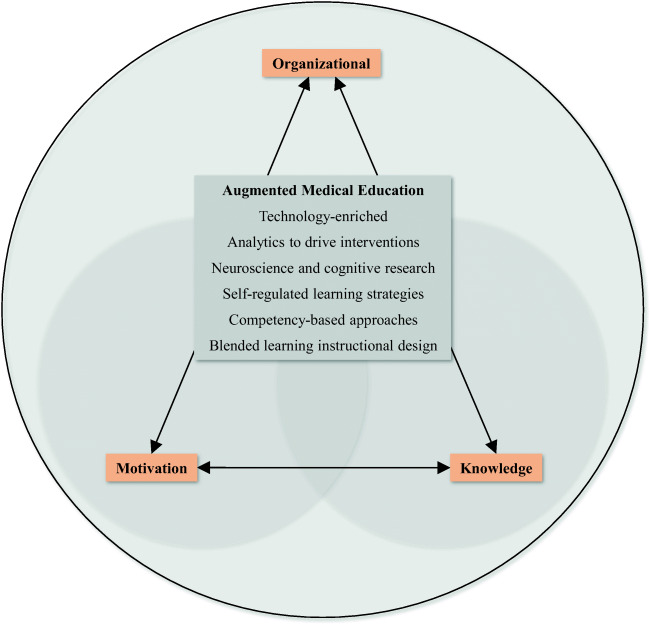

Careful fusion of the best elements of digital learning and face-to-face interactions creates novel approaches to medical education enhancements and curriculum delivery. Thus, implementing school-specific augmented medical education initiatives requires the use of best practices for instructional design. The six foundational components of the school-specific augmented medical education model are grounded in educational best practices and include the following: technology-enriched learning environments, analytics to drive instructional interventions, cognitive neuroscience and educational psychology research (the Science of Learning), self-regulated learning strategies, competency-based approaches, and blended learning instructional design (Fig. 1). Table 1 describes the foundational elements of school-specific augmented medical education (AME), which would likely yield optimal site-specific curriculum delivery with enriched student interactions.

Fig. 1.

School-specific augmented medical education is grounded in educational best practices, and features six foundational elements. However, in the absence of strategic planning and effective leadership, successful curriculum delivery would likely be limited by the interactions of knowledge, motivation, and organizational influences [3, 12]. In this illustration, the organization represents medical school leadership. This organization would define a strategic performance goal related to implementing augmented medical education elements into their curricula. Then, by applying the Clark and Estes’ gap analysis procedures, stakeholder knowledge, motivation, and organizational needs could be identified [12]. Evidence-based solutions could then be implemented and assessed so that organizational performance goals could be achieved

Table 1.

Primer for the foundational elements of the site-specific augmented medical education (AME) model aligned with pedagogical best practices

| AME Component | Literature | Best practices with relevance to AME |

|---|---|---|

| Technology-enriched learning environments | • Duffy MC, Azevedo R. (2015, November). Motivation matters: Interactions between achievement goals and agent scaffolding for self-regulated learning within an intelligent tutoring system. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 338–348. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.041 | • Technology-enriched learning environments necessitate carefully-designed educational experiences, where physicians-in-training practice self-regulated learning strategies. Instructional design strategies enable affective, behavioral, cognitive, and socio-cultural learner engagement. Throughout the UME curriculum, traditional lectures (in many cases) would be replaced with mobile-friendly digital learning assets, autonomous AR/VR simulation exercises, and self-guided learning modules. |

| • Moos DC, Bonde C. (2016). Flipping the classroom: Embedding self-regulated learning prompts in videos. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 21(2), 225–242. doi:10.1007/s10758-015-9269-1 | ||

| • Plass JL, Homer BD, Kinzer CK. (2015). Foundations of Game-Based Learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 258–283. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533 | ||

| • Ruthenbeck G, Reynolds K. (2015). Virtual reality for medical training: The state-of-the-art. Journal of Simulation, 9(1), 16–26. doi:10.1057/jos.2014.14 | ||

| Analytics to drive interventions | • ECAR-ANALYTICS Working Group. The Predictive Learning Analytics Revolution: Leveraging Learning Data for Student Success. ECAR working group paper. Louisville, CO: ECAR, October 7, 2015. Pp. 1–23. Retrieved from: https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2015/10/ewg1510-pdf.pdf | • Data-driven organizations improve learner outcomes by using predictive learning analytics to guide educational interventions with individual medical students. During the instructional design process, learning analytics would be linked with decision-making processes to inform stakeholders and instructors. Given the potential that learning analytics can often be unclear and not necessarily tied to improved learning outcomes, quality indicators with criterion would guide the use of learning analytics in undergraduate medical education. Novel approaches using the Internet of Things (IoT) provide real-time data to educators, so that targeted educational interventions could be implemented during educational experiences. |

| • Persico D, Pozzi F. (2015). Informing learning design with learning analytics to improve teacher inquiry. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2), 230–248. doi:10.1111/bjet.12207 | ||

| • Scheffel M, Drachsler H, Stoyanov S, Specht M. (2014). Quality indicators for learning analytics. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 17(4), 117–132. Retrieved from http://libproxy.usc.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.libproxy1.usc.edu/docview/1660157092?accountid=14749 | ||

| • Strang KD. (2016). Do the critical success factors from learning analytics predict student outcomes? Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 44(3), 273–299. doi:10.1177/0047239515615850 | ||

| • Kredell M. (2018, Summer). CHARIOT begins testing wearable technology. Retrieved October 7, 2018, from https://rossier.usc.edu/magazine/ss2018/chariot-begins-testing-wearable-technology/ | ||

| Neuroscience and cognitive research (The Science of Learning) | • Anguera JA, Boccanfuso J, Rintoul JL, Al-Hashimi O, Faraji F, Janowich J, Kong E, Larraburo Y, Rolle C, Johnston E, Gazzaley A. (2013). Video game multitasking training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature, 501, (September), 97–101. doi:10.1038/nature12486 | • Neuroscience research and metacognitive strategies guide the design and development of site-specific augmented medical education learning environments, which adapt to meet individual learner needs. Social and emotional factors, prior knowledge, and individual learner characteristics drive successful instructional design within undergraduate medical education curricula. Thus, within technology-enriched learning environments, effective learning is facilitated when instruction increases germane cognitive load by engaging the learner in meaningful learning and schema construction. |

| • Homer BD, Plass JL, Blake L. (2008). The effects of video on cognitive load and social presence in multimedia learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(3), 786–797. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2007.02.009 | ||

| • Immordino-Yang MH, Christodoulou JA, Singh V. (2012). Rest is not idleness: Implications of the brain’s default mode for human development and education. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 7(4), 352–364. doi: 10.1177/1745691612447308 | ||

| • Schraw G, McCrudden M. (2006). Information processing theory. Retrieved from: http://www.education.com/reference/article/information-processing-theory/. | ||

| • Kirschner P, Kirschner F, Paas F. (2006). Cognitive load theory. Retrieved from: http://www.education.com/reference/article/cognitive-load-theory/. | ||

| Self-regulated learning strategies | • Azevedo R, Cromley JG, Moos DC, Greene JA, Winters FI. (2011). Adaptive content and process scaffolding: A key to facilitating students’ self-regulated learning with hypermedia. Psychological Testing and Assessment Modeling, 53(1), 106–140. Retrieved from: http://search.proquest.com.libproxy1.usc.edu/docview/1399687107? accountid = 14,749 | • Within technology-enriched learning environments, content and process scaffolding facilitates medical students’ self-regulated learning. Instructional design must minimize extraneous cognitive load by incorporating adaptable learner-centered interactions that promote metacognitive behaviors. These types of interactions are based, in part, on learners’ prior knowledge levels. |

| • Song SH, Pusic M, Nick MW, Sarpel U, Plass JL, Kalet AL. (2014, February). The cognitive impact of interactive design features for learning complex materials in medical education. Computers and Education, 71, 198–205. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.09.017 | ||

| • Taub M, Azevedo R, Bouchet F, Khosravifar B. (2014, October). Can the use of cognitive and metacognitive self-regulated learning strategies be predicted by learners’ levels of prior knowledge in hypermedia-learning environments? Computers in Human Behavior, 39, 356–367. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.018 | ||

| Competency-based approaches | • Englander R, CameronT, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. (2013). Toward a common taxonomy of competency-based domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1088–1094. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b | • The infrastructure of a shared curricular ecosystem relies on general physician competencies to determine learner mastery of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors. Assessment strategies for competency-based medical education (CBME) are evolving, but increased accountability, transparency, and effectiveness are driving systemic change and curricular overhauls. Improved formative feedback and student-faculty relationships are just two of many advantages when CBME approaches are implemented. |

| • Hawkins RE, Welcher CM, Holmboe ES, Kirk LM, Norcini JJ, Simons KB, Skochelak SE. (2015). Implementation of competency-based medical education: Are we addressing the concerns and challenges? Medical Education, 49(11), 1086–1102. doi:10.1111/medu.12831 | ||

| • Levine MF, Shorten G. (2016). Competency-based medical education: Its time has arrived. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal Canadien d’Anesthésie, 63(7), 802–806. doi:10.1007/s12630-016-0638-6 | ||

| • Pettepher CC, Lomis KD, Osheroff N. (2016). From theory to practice: Utilizing competency-based milestones to assess professional growth and development in the foundational science blocks of a pre-clerkship medical school curriculum. Medical Science Educator, 26(3), 491–497. doi:10.1007/s40670-016-0262-7 | ||

| Blended learning instructional design | • Garrison D, Vaughan N. (2008). Blended learning in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. | • Blended learning environments require careful consideration, in that the best elements of face-to-face (F2F) instruction are fused with the best elements of computer-assisted learning. Medical students would engage in sustained learning environments that transcend convenience and efficiency. Integration of F2F instruction with technology-driven learning assets requires organizational commitment and fundamental medical educator role-changes. But, the resulting educational space provides many opportunities to infuse high-impact educational strategies, such as simulation education. |

| • Garrison D, Vaughan N. (2013). Institutional change and leadership associated with blended learning innovation: Two case studies. Internet and Higher Education, 18, 24–28. | ||

| • McGee P, Reis A. (2012). Blended Course Design: A Synthesis of Best Practices. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 16(4): 7–22. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.libproxy1.usc.edu/ps/i.do?p=AONE&sw=w&u=usocal_main&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA302298974&sid=summon&asid=a03339e2a5cb05e2b76a495f48695c57 | ||

| • Strayer JF. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learning Environments Research, 15(2), 171–193. doi:10.1007/s10984-012-9108-4 | ||

| • Motola I, Devine LA, Chung HS, Sullivan JE, Issenberg SB. (2013). Simulation in healthcare education: a best evidence practical guide. AMEE Guide No. 82. Medical Teacher, 35(10), e1511-e1530. |

Emergence of Practical Solutions for Medical Education

Medical education’s paradigm shift is here. Contemporaneous reform efforts are redefining preclinical medical education experiences. Chen, van den Broek, and ten Cate described the types of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) that are most relevant to undergraduate medical education (UME) and proposed how they could be evaluated [7]. Furthermore, they defined a potential framework for competency-based undergraduate medical education by aligning the incorporation of EPAs in a scaffolded approach with the continuum of the UME experience. Hurtubise, et al. proposed an example of a competency-based flipped classroom model, where they outlined organizational change management strategies related to coalition-building, communicated vision, demonstrating successes, faculty development, and inquiry-based culture shifts [13]. Mehta et al. provided a review of innovative practices that are disrupting medical education and proposed a digital-badging strategy that links competency-based education (with EPAs) by tracking student mastery of activities [8]. Preclinical medical education reform initiatives aim to replace traditional didactic sessions with blended-learning strategies that integrate experiential and competency-based strategies.

Building curiosity enriches the learning experiences for physicians in training. Prober and Heath envisioned a blended-learning experience where traditional lectures were replaced with short videos accompanied by self-assessment questions, so that opportunities for meaningful faculty-student discussions were maximized [14]. Prober and Khan disrupted the traditional culture and made the official call to “reimagine medical education” by explaining a technology-supported curriculum model where students are encouraged to pursue personalized deeper dives into areas of personal interest [10]. Le and Prober then proposed a shared curricular ecosystem model to conserve scarce resources, while providing a common high-quality educational experience [5]. Consequently, school-specific augmented medical education curricula would promote learner-centered experiences that feature carefully designed technology-enriched learning environments. Implementing such complex initiatives necessitates role changes and new critical behaviors from key stakeholders (including medical school leadership, instructors, and learners). Thus, practical recommendations to implement these strategic overhauls are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Practical recommendations to implement augmented medical education initiatives aligned with key stakeholder groups

| Stakeholder group | Practical recommendations for implementation |

|---|---|

| Leadership | • Establish a shared vision for medical school-specific augmented medical education. |

| • Establish measurable performance goals. | |

| • Generate novel accountability mechanisms aligned with strategic plan and critical behaviors. | |

| • Provide human capital, allocate fiscal resources, and create spaces for faculty development. | |

| • Conduct knowledge, motivation, and organizational needs analyses to inform decision-making processes. | |

| • Communicate organizational-level successes and opportunities-for-growth openly with all critical stakeholders in a transparent manner. | |

| Instructors | • Align instructional activities with measurable learning objectives when delivering their sessions. |

| • Generate opportunities for learners to apply academic content to authentic and clinical scenarios. | |

| • Create opportunities for learners to reflect on their learning experiences. | |

| • Ensure that learners forge meaningful interactions with peers and instructors. | |

| • Incorporate competency-based and mastery-based assessments (in place of multiple choice knowledge exams). | |

| • Use learning analytics to inform individualized educational interventions. | |

| • Provide formative and summative assessment data to learners. | |

| • Craft individualized feedback narratives for learners, which communicate successes and opportunities for growth. | |

| • Participate as subject matter experts in the collaborative and iterative process of curricular (re)designs. | |

| • Engage in metacognitive processes to reflect on professional development as an educator. | |

| Learners | • Actively engage in online and face-to-face learning opportunities. |

| • Dedicate significant effort to employing self-regulated learning strategies (in place of rote memorization). | |

| • Collaborate with peers and instructors to enrich the learning experience. | |

| • Respond to formative and summative feedback in a reflective manner. | |

| • Use learning analytics to inform and self-monitor progress. | |

| • Synthesize deliverables that demonstrate learning. |

Technology-Enriched Learning Environments

Technology-enriched learning environments provide the digital instructional mechanisms to support novel approaches to competency-based medical education. Aronson, Plass, and Bania suggested opening new research that is aimed at determining specific characteristics of an educational intervention so that the most effective personalized educational experience can be achieved [15]. In a meta-analysis, where 2705 articles were reviewed, Cook et al. suggested that interactivity, practice exercises, repetition, and feedback were associated with improved learning outcomes in technology-enriched learning environments [16]. Indeed, Grunwald and Corsbie-Massay presented guidelines for educational strategies, cognitive load, and interface design [17].

Analytics to Drive Educational Interventions

Learning analytics support modern teaching and learning needs [18]. Using learning analytics in medical education is beginning to guide policy-making by improving and customizing how academic content is delivered to improve the learning experiences for physicians in training [19]. Simultaneously, medical education learning spaces are evolving away from traditional lecture halls and now include online interactions, collaborative/social sessions, and experiential/community-based opportunities. Analytics may provide instructors and learners with real-time information about course engagement, assessments, and learning metrics [20]. Students may use these data for self-monitoring of their own performance, while instructors may use this same information to inform their individualized and real-time educational interventions. Moreover, research with wearables and the Internet-of-Things (IoT) is fine-tuning the degree to which individualized data can be used to improve the learning experience in classrooms [21]. The careful and ethical alignment of learner data with instructional design and course delivery yields new opportunities for reconceptualizing the modern classroom and participant roles.

Neuroscience and Cognitive Research (The Science of Learning)

Recent advances in neuroscience research increase understanding of cognitive control, neural processes, and neural-plasticity [22]. During the instructional design process, personalized lessons can be developed that meet an individual’s needs based on their prior (incoming) knowledge [23]. For example, Anguerra et al. highlighted that goal-directed behaviors drive human learning, when technology-enriched learning experiences intersect with medical education [24]. Moreover, customized learning experiences via video games demonstrated the underlying neural mechanisms that serve as tools for cognitive development [24]. Berman, Fall, Maloney, and Levine argued for using appropriate and integrated computer-assisted instruction (CAI) to improve medical education, where assessment of skills and mastery could be enhanced [25]. Mayer sought to apply the science of learning to medical education and identified research-based principles for instructional design of multimedia lessons (cognitive theory of multimedia learning), which included reducing extraneous processing, managing essential processing, and fostering generative processing [26].

Self-Regulated Learning Strategies

Academic successes are positively influenced when learners engage in metacognitive behaviors, where they reflect on their study strategies and learn how to control their own learning [27]. During the development of novel medical education interventions, stakeholders need to understand learner use of self-regulated strategies, which include the following: learner motivation, methods of learning, time management, physical and social environments, goal-setting, and self-monitoring of performance [28, 29]. Medical educators can monitor learners’ uses of self-regulated learning strategies within technology-enriched learning environments by employing tools like the self-regulation measure for computer-based learning [6]. Evidence collected with this type of a tool can help inform improvements to the curriculum over time so that learners benefit from the learning experiences.

Competency-Based Approaches

Competency-based learning strategies are emerging as solutions for preclinical medical education reform efforts [30]. In addition to articulating a reference list of general physician competencies, Englander et al. provided standardized language and competencies for future benchmark comparisons, evaluations, and research [31]. Hawkins et al. outlined the challenges and concerns related to implementing competency-based medical education (CBME) strategies and argued for evidence-based practices that articulate consistent definitions and frameworks for CBME [32]. Levine and Shorten argued for precisely defined criteria and increased opportunities for frequent formative feedback for learner-centered CBME programs to be successful, fair, transparent, and meaningful [33]. Emerging solutions to medical education reform necessitate the use of national physician competencies embedded within core curricular activities [30]. Implementing competency-based approaches to preclinical medical education creates mechanisms for physicians-in-training to demonstrate mastery of core concepts and expected behaviors.

Blended Learning Instructional Design

Blended-learning pedagogical designs support competency-based curricular overhauls [34]. Blended designs are flexible alternatives to traditional didactic lectures, where competency-based learning strategies can be featured [13]. In medical education, well-designed blended learning course redesigns lead to improved student satisfaction and increased academic performance [35–37]. However, with these successes, research is needed that specifically links blended-learning pedagogical designs with competency-based medical education.

Conclusion

During this current paradigm shift in medical education, opportunities exist to reinvent the educational experiences for both educators and physicians in-training alike [5, 7–11, 14, 34]. For example, technology-enriched learning environments potentially offer personalized lessons that reduce extraneous cognitive load and maximize academic performance [38, 39]. By drawing on intersections between neuroscience research, cognitive behaviors, and digital learning environments, Immordino-Yang recommended that learners should not be merely dependent upon the technology for information, but instead, they should be interacting with technology in ways that allows them to demonstrate mastery in novel ways [40]. Currently, medical education programs are launching computer-assisted instruction, but more empirical studies are needed to ensure that effective interface designs are aligned with current neuroscience research and cognitive theory. Specifically, research is lacking that aligns technology-enriched learning initiatives with competency-based medical education.

Limitations to adopting and implementing this school-specific augmented medical education model faces knowledge, motivation, and organizational barriers [3, 12]. Furthermore, these barriers would be unique to each medical school, and to each stakeholder group. For example, some educators would need procedural knowledge of how to build blended learning environments based on educational best practices by using shared curricular resources [3]. And from a motivational perspective, some educators would need to value the extra effort they spend in redesigning their modules [41, 42]. They would also need to expect that their extra effort spent directly yields improved student outcomes [41]. Novel accountability mechanisms would need to be established that align organizational-level performance goals with a shared vision and stakeholder expectations [43, 44]. Thus, within this cultural change, leadership will need to prioritize faculty development initiatives by providing adequate human capital, fiscal resources, and physical creativity spaces [3, 45, 46].

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Melora Sundt, Kenneth Yates, Monique Datta, and Kathy Hanson. Additionally, conversations with Charles Prober aided with streamlining and improving this manuscript. Importantly, the author wishes to thank the Educational Development Office’s Division of Innovations in Medical Education at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine for support and assistance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Previous Presentations

Portions of this work originated as part of the author’s dissertation study at the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Garrison D, Vaughan N. Blended learning in higher education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrison D, Vaughan N. Institutional change and leadership associated with blended learning innovation: two case studies. Inter High Edu. 2013;18:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DP. A Gap Analysis of Course Directors’ Effective Implementation of Technology-enriched Course Designs: An Innovation Study [dissertation]. Los Angeles, Ca: University of Southern California. 2018. Retrieved from the University of Southern California Digital Library: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll40/id/462270. Accessed 30 May 2018.

- 4.VanDerLinden K. Blended learning as transformational institutional learning. New Dir High Edu. 2014;165:75–85. doi: 10.1002/he.20085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le TT, Prober CG. A proposal for a shared medical school curricular ecosystem. Acad Med. 2018;93:1125–1128. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song HS, Kalet AL, Plass JL. Assessing medical students’ self-regulation as aptitude in computer-based learning. Adv Health Sci Edu. 2011;16(1):97–107. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9248-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen HC, van den Broek WS, ten Cate O. The case for use of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):431–436. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB, Stoller JK. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1418–1423. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a36a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller BM, Moore DE, Jr, Stead WW, Balser JR. Beyond Flexner: a new model for continuous learning in the health professions. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):266–272. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c859fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1407–1410. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a368bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Touchie C, Cate O. The promise, perils, problems and progress of competency-based medical education. Med Edu. 2016;50(1):93–100. doi: 10.1111/medu.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark RE, Estes F. Inc. 2008. Turning research into results: A guide to selecting the right performance solutions. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurtubise L, Hall E, Sheridan L, Han H. The flipped classroom in medical education: engaging students to build competency. J Med Edu Curr Dev. 2015;2:35–43. doi: 10.4137/JMECD.S23895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prober CG, Heath C. Lecture halls without lectures--a proposal for medical education. NEJM. 2012;366(18):1657–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1202451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronson ID, Plass JL, Bania T. Optimizing educational video through comparative trials in clinical environments. Edu Tech Res Dev. 2012;60(3):469–482. doi: 10.1007/s11423-011-9231-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Instructional design variations in internet-based learning for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2010;85(5):909–922. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d6c319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grunwald T, Corsbie-Massay C. Guidelines for cognitively efficient multimedia learning tools: educational strategies, cognitive load, and interface design. Acad Med. 2006;81(3):213–223. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JE, Recker M. What do studies of learning analytics reveal about learning and instruction? A systematic literature review. Learn, des, and tech: intl comp theory, res, prac, and pol. 2018;2018:1–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-17727-4_116-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan T, Sebok-Syer S, Thoma B, Wise A, Sherbino J, Pusic M. Learning analytics in medical education assessment: the past, the present, and the future. AEM Edu and Train. 2018;2(2):178–187. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cirigliano MM, Guthrie C, Pusic MV, Cianciolo AT, Lim-Dunham JE, Spickard A, III, Terry V. Yes, and … exploring the future of learning analytics in medical education. Teach and Learn in Med. 2017;29(4):368–372. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2017.1384731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kredell M. “CHARIOT begins testing wearable technology”. 2018. Summer. Retrieved October 7, 2018, from: https://www.rossier.usc.edu/magazine/ss2018/chariot-begins-testing-wearable-technology/. Accessed 30 May 2018.

- 22.Immordino-Yang MH, Christodoulou JA, Singh V. Rest is not idleness: Implications of the brain's default mode for human development and education Perspec on. Psy Sci: Assoc for Psy Sci. 2012;7(4):352–364. doi: 10.1177/1745691612447308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taub M, Azevedo R, Bouchet F, Khosravifar B. Can the use of cognitive and metacognitive self-regulated learning strategies be predicted by learners’ levels of prior knowledge in hypermedia-learning environments. Comp Edu. 2014;39(October):356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.07.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anguera JA, Boccanfuso J, Rintoul JL, Al-Hashimi O, Faraji F, Janowich J, Kong E, Larraburo Y, Rolle C, Johnston E, Gazzaley A. Video game multitasking training enhances cognitive control in older adults. Nature. 2013;501(September):97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berman NB, Fall LH, Maloney CG, Levine DA. Computer-assisted instruction in clinical education: a roadmap to increasing CAI implementation. Adv in Health Sci Edu. 2008;13(3):373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning to medical education. Med Edu. 2010;44(6):543–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning. Boston, MA: Pearson Education; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dembo MH, Seli H. Academic self-regulation. In: Dembo MH, Seli H, editors. Motivation and learning strategies for college success: a focus on self-regulated learning. 5. New York, N.Y: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, Inc; 2016. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zimmerman BJ. Academic studying and the development of personal skill: a self-regulatory perspective. Edu Psy. 1998;33(2):73–86. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep3302&3_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettepher CC, Lomis KD, Osheroff N. From theory to practice: utilizing competency-based milestones to assess professional growth and development in the foundational science blocks of a pre-clerkship medical school curriculum. Med Sci Edu. 2016;26(3):491–497. doi: 10.1007/s40670-016-0262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Englander R, Cameron T, Ballard AJ, Dodge J, Bull J, Aschenbrener CA. Toward a common taxonomy of competency-based domains for the health professions and competencies for physicians. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1088–1094. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3b2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawkins RE, Welcher CM, Holmboe ES, Kirk LM, Norcini JJ, Simons KB, Skochelak SE. Implementation of competency-based medical education: are we addressing the concerns and challenges? Med Edu. 2015;49(11):1086–1102. doi: 10.1111/medu.12831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine MF, Shorten G. Competency-based medical education: its time has arrived. Can J Anes. 2016;63(7):802–806. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green DP. Next generation medical education: facilitating student-centered learning environments. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative Brief. 2016; 1–6. Retrieved from: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2016/3/next-generation-medical-education. Accessed 30 May 2018.

- 35.Morton CE, Saleh SN, Smith SF, Hemani A, Ameen A, Bennie TD, Toro-Troconis M. Blended learning: how can we optimise undergraduate student engagement? BMC Med Edu. 2016;16(1):195–202. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0716-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connor EE, Fried J, McNulty N, Shah P, Hogg JP, Lewis P, et al. Flipping radiology education right side up. Acad Rad. 2016;23(7):810–822. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wood ML, Forgie SE. A first step to blended delivery: introducing an online component to an infectious diseases course using a photography-based social media platform. Med Sci Edu. 2015;25(2):101–103. doi: 10.1007/s40670-015-0103-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalet AL, Song HS, Sarpel U, Schwartz R, Brenner J, Ark TK, Plass J. Just enough, but not too much interactivity leads to better clinical skills performance after a computer assisted learning module. Med Tea. 2012;34(10):833–839. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.706727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song SH, Pusic M, Nick MW, Sarpel U, Plass JL, Kalet AL. The cognitive impact of interactive design features for learning complex materials in medical education. Comp Edu. 2014;71(February):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Immordino-Yang MH, Singh V. Perspectives from social and affective neuroscience on the design of digital learning technologies. In: Immordino-Yang MH, editor. Emotions, learning, and the brain: Exploring the educational implications of affective neuroscience. New York, N.Y: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc; 2016. pp. 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eccles J. Expectancy value motivational theory. In: Anderman EM, Anderman LH, editors. Psychology of Classroom Learning, vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA: Detroit; 2006. p. 390–3. Retrieved from: http://go.galegroup.com.libproxy1.usc.edu/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3027800112&sid=summon&v=2.1&u=usocal_main&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w&asid=6ab39823387b6b715067288033f65e7c. Accessed 30 May 2018.

- 42.Pintrich PR. A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. J Edu Psy. 2003;95(4):667–686. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elmore RF. Bridging the gap between standards and achievement. Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute. 2002. Retrieved July 12, 2003, from http://www.shankerinstitute.org/resource/bridging-gap-between-standards-and-achievement. Accessed 30 May 2018.

- 44.Hentschke GC, Wohlstetter P. Cracking the code of accountability. Univ S Calif Urban Educ. 2004;2004(Spring/Summer):17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graham CR, Woodfield W, Harrison JB. A framework for institutional adoption and implementation of blended learning in higher education. Inter High Edu. 2013;18:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Porter WW, Graham CR, Bodily RG, Sandberg DS. A qualitative analysis of institutional drivers and barriers to blended learning adoption in higher education. Inter High Edu. 2016;28:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]