Abstract

Student-run, physician-supervised free clinics (SRFCs) provide essential healthcare services for many uninsured and underinsured patients in the USA. While SRFCs serve diverse populations and offer distinct services, they face many similar barriers to successful clinic operation. Historically, the sharing of best practices and development strategies across SRFCs has been limited and insufficient for both new and emerging free clinics. To address these challenges, in 2015, the East Harlem Health Outreach Program (EHHOP) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai formed the EHHOP Consulting Group (ECG), with the goal of providing client SRFCs individualized support from medical students. ECG draws from the experience of EHHOP and other veteran SRFCs to provide customized solutions to best address client SRFC needs. Here, we describe ECG’s inception, structure, and consulting work with client SRFCs. We propose that this interactive, longitudinal model can be adapted to other healthcare trainee initiatives where cross-institutional collaboration could prove beneficial.

Keywords: Information-sharing, Student-run, Free clinics, Consulting, Medical students

Background

Despite provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010) [1], a major proportion of Americans remained un- or underinsured. In 2016, over 32 million people in the USA were uninsured [2]. As of March 2019, more than 2 million uninsured people were ineligible for Medicaid (1965) [3] because they live in states that have not passed Medicaid expansion [4]. Many uninsured patients are dependent on free clinics for essential healthcare services, including both primary care and specialty services. Student-run free clinics (SRFCs) serve an important role in the landscape of safety-net health providers by delivering primary healthcare services to the nation’s uninsured while providing unique service experiences for health professions students. Students at SRFCs predominantly provide outpatient primary care services under the supervision of attending physicians, while the specific type of care provided can vary based on the specialty and training of the attending provider. Many future physicians are currently enhancing their formal medical education through service work in SRFCs. As of 2014, over three-quarters of US medical schools were affiliated with an SRFC, and more than half of medical students at these schools were involved in their corresponding SRFC [5]. While there is significant diversity in populations served and services offered among SRFCs, these clinics face common challenges in clinic structure and function. The development and sharing of best practices could maximize the ability of SRFCs to provide optimal clinical care. However, such collaboration has historically been hindered by geographic, institutional, and temporal barriers, as SRFCs are run by medical students who may be isolated from the work of other SRFCs, still learning to operate their own clinics, and primarily busy with their academic work.

Similar to other models of healthcare delivery, research and innovations among SRFCs are disseminated through conferences and publications and via national and local organizations. The Society of Student-Run Free Clinics (SSRFC) [6] was started in 2010 to promote collaboration among clinics, in part, through hosting a national annual conference. This conference draws hundreds of SRFC participants and serves as a platform for sharing research and innovations. The SSRFC also publishes the peer-reviewed Journal of Student Run Clinics, which hosts a growing body of scholarly literature related to SRFCs. Additionally, SSRFCs draw from overarching guidelines for best practices in clinical care developed by larger bodies of medical professionals, such as the American Medical Association, and government organizations, such as the Food and Drug Administration, the Institute of Medicine, and the US Preventive Services Task Force.

The SSRFC has a role in facilitating the exchange of ideas and information between clinics across the nation, but does not currently provide individualized guidance to SRFCs in a longitudinal fashion. Both conference proceedings and journal articles tend to describe the activities of individual clinics, which often vary significantly in scope of practice, resources, and operational structure and may not be applicable to the evolving and longitudinal stresses of nascent and developing SRFCs. Furthermore, extrapolation from such resources can be daunting for trainees with little experience in clinic operation. SRFCs also face unique challenges among practice settings in their degree of personnel turnover, financial limitations, and dependence on faculty support. There is a paucity of resources that take into account local and regional factors that influence SRFC function. State-specific legislation pertinent to underserved populations commonly served by SRFCs, for example, Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, requires more tailored resource sharing. For these reasons, SRFCs may benefit from more direct and customized assistance from fellow students at SRFCs with more experience.

One of the most important goals of SRFCs is encouraging student peer- and inter-professional learning. Often, senior students teach junior students under the guidance of faculty physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. This collaboration between students and faculty within each clinic is essential to the delivery of quality patient care. We aimed to foster working relationships between students at different institutions that could take advantage of some of the established benefits of this type of near peer learning. A secondary goal of ECG was therefore to provide a more directed framework for the sharing of inter-institutional knowledge and overarching best practices.

Blueprints for this kind of endeavor have been severely lacking. To this end, in 2015, the East Harlem Health Outreach Partnership (EHHOP), the SRFC of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, launched the EHHOP Consulting Group (ECG). ECG is a medical student organization that offers multimodal support to SRFCs in any stage of development, in order to offer individualized guidance to the needs of client SRFCs in a longitudinal fashion. This type of resource sharing did not exist until ECG was launched, marking an innovative method to resource share with dedicated student consultants, allowing for a tailored approach aimed at sustainability. Herein, we describe the first 4 years of the evolution of this unique service as a consulting resource to nascent and established SRFCs.

Design of EHHOP Consulting Group

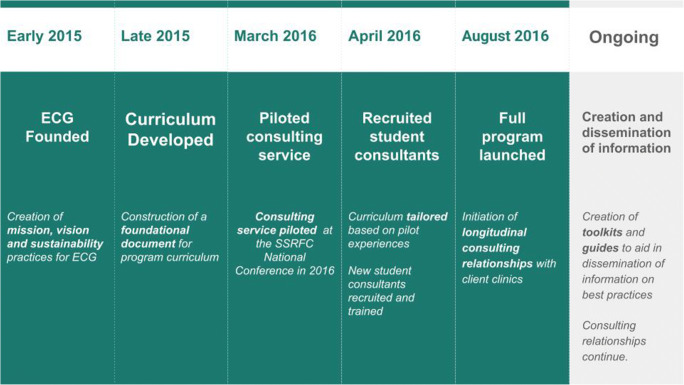

Recognizing the need for improved information sharing on best practices, the program director of EHHOP assembled a team of founding medical students in 2015 to develop a curriculum for the future EHHOP Consulting Group (outlined in Fig. 1), with support from a generous donation by the Atran Foundation [7]. This grant supplied funding for the creation of a resource compendium, and continues to provide support to ECG’s goal of aiding SRFCs through consulting individual clinics. Founding student members collaborated with graduate organizational psychology students at Teachers College, Columbia University [8], and received training on foundational skills through interactive workshops in developing team dynamics and leadership structure, formulating rubrics for strategic planning, and establishing mission and vision of the nascent ECG. Further details and examples of training sessions for consultants are illustrated in Table 1. EHHOP faculty provided longitudinal supervision, advising support, trouble-shooting, and guidance on strategic planning and scholarship. Faculty also helped develop connections and partnerships with other medical schools. However, faculty did not attend ECG meetings, which were led entirely by student members of the group.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of the formation and development of the EHHOP Consulting Group

Table 1.

Training modules for student consultants

| Training module | Trainer | Session objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational principles applied to student-run endeavors |

• Organizational psychology students • Free clinic student leadership, for example, ECG Chair |

Exposure to organizational principles including but not limited to: • Clinic workflow • Leadership • Group dynamics • Personnel recruitment/selection • Job analysis Learn the nuts and bolts of running a clinic |

| Consulting methods |

• Outside consulting expert For example, consulting employee or MBA student |

Learn basic methods and strategies of consulting Consider unique challenges of working with students Develop strategies for effective client–consultant interactions |

| Consulting case practice | • Outside consulting expert | Apply consulting methods to practice cases |

| Principles of caring for underserved populations |

• Physician volunteer at free clinic • Faculty involved in community health work |

Consider unique challenges of caring for an underserved population Consider social determinants of health |

| Additional Sessions Pertinent to Local Challenges/Populations |

• Local physicians or community advocates • Faculty involved in community health work |

Specific sessions vary by clinic and could include, for example, how to care for a homeless population |

These can be adjusted and supplemented with additional programming as needed. Learning continues informally after official training is complete by discussion with more senior consultants and “on the job” experience with clients

The first client clinics were recruited through networking and tabling at the national SSRFC conference. Internally, student consultants are recruited by ECG directly through an application and interview process. While prior business and consulting experience is not required, ECG seeks students with prior experience at EHHOP as well as a genuine interest in learning more about consulting, giving students exposure to different aspects of the practice of medicine. New student consultants were trained in the basics of SRFC operations as well as in consulting skills, specifically how to find creative approaches to common problems that SRFCs face. Building successful and productive client–consultant relationships is also emphasized in the training.

ECG consultants communicate with their clients in several ways including email, conference calls, and video conferencing. In addition, ECG consultants have conducted site visits to client clinics, and representatives from client clinics have visited EHHOP to observe clinic flow and meet with clinic leaders. Internal ECG meetings are discussion based, and led by ECG members on a rotating basis; such structure allows its own members develop and refine leadership skills, which are important for building successful consulting relationships and can positively shape individual careers in health profession leadership.

In interfacing with clients, ECG utilizes a series of three electronic tools. The first tool is the initial assessment tool (IAT). The IAT is a short screening tool for ECG to gain information about new client SRFCs and what problems they seek to address with ECG’s help. After a new client fills out the IAT, a member of ECG will contact the clinic to arrange a telephone meeting. During this telephone meeting, the client and their respective ECG consultant will fill out the second tool, a clinic demographics survey, which includes questions on patient populations seen, clinic day flow, management, and financial and institutional support. Conducting this survey on the phone serves several purposes: it allows for further discussion in each of these areas, helps clarify the strengths and weaknesses of the clinic, and strengthens the client-consultant relationship.

Using the information from the clinic demographics survey, consultants then conduct a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis on the clinic, which helps identify the most high-impact areas for intervention in order to improve clinic function [9]. Based on the SWOT analysis, consultants work with their clients to develop and refine specific goals for the year. This approach was based on the “SMART” goals model, which seeks to create goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time bound [10]. ECG members then worked to meet these predefined goals with their clients through site visits, workshops, and leadership consultations.

Client evaluation of progress is critical to ensuring success and the ability of ECG to meet future clients’ needs. As the landscape of healthcare in the USA undergoes dramatic changes, the needs of SRFCs are especially affected by these shifts. These needs vary greatly, from funding to staffing, to refining existing approaches to provide the highest-quality care. ECG solicits feedback from its clients via a third electronic assessment tool, the follow-up assessment tool (FAT), to track how well clients are accomplishing goals. The form includes a series of questions regarding the client’s satisfaction with the consulting services as well as a free response section for clients to communicate next steps and potential new goals. The results of the FAT are used to guide further improvements of ECG services to best meet client needs year after year.

ECG Clients

Between ECG’s inception in 2015 and 2018, ECG consultants have worked with a total of 15 client SRFCs. Of these clinics, 10 had been established prior to working with ECG, whereas 5 clinics were in the process of launching. Table 2 distinguishes each client clinic by geographic region, stage of development, and main project with ECG. The clinics are located throughout the mainland USA, with five clinics in the northeast, five clinics in the midwest, three in the west, and two in the south.

Table 2.

Client clinic demographics and main projects

| Clinic | Region | Stage | Main project with ECG |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Midwest | New | Establishing EMR |

| 2 | Northeast | New | Fundraising and budgeting |

| 3 | South | New | Clinic workflow |

| 4 | West | New | Liability coverage |

| 5 | Midwest | New | Community outreach |

| 6 | South | Established | Ancillary services |

| 7 | Midwest | Established | Pharmacy |

| 8 | Northeast | Established | Expand patient base |

| 9 | Northeast | Established | Strategic planning |

| 10 | West | Established | Leadership transitions |

| 11 | Northeast | Established | Patient recruitment |

| 12 | Midwest | Established | Grant writing |

| 13 | West | Established | Ancillary clinic workflow |

| 14 | Midwest | Established | Budgeting |

| 15 | Northeast | Established | Health screening |

SFRCs can be distinguished as one of two types based on clinic model: clinics that operate with a transitional model provide care on a short-term or episodic basis and may transition care to local safety-net practices or operate as a connection to medical homes for patients eligible for insurance; clinics that operate with a continuity model follow patients longitudinally and may serve as a medical home. All of the clinics target underserved populations, but the eligibility requirements for each clinic vary greatly and may include geographical restrictions, age-related cut-offs, health insurance, and citizenship status, and other criteria. Clinics may focus on select populations; some clinics primarily serve refugees and most serve exclusively uninsured patients. Nearly all have a large proportion of immigrant persons, and some are exclusive to homeless persons. While all of ECG’s client clinics have served adult populations, according to a 2013 article characterizing SRFCs at 86 US medical schools [5], 39.5% of SRFCs offered pediatric services. ECG consultants work with clients for varying amounts of time that range from a one-time consultation to relationships for multiple years, depending on the needs of the client. ECG helps clients meet a variety of needs with the most common including the following: establishing electronic medical record (EMR), grant writing and budgeting, optimizing clinic workflow, patient recruitment, and expanding clinic capabilities for patients. For example, based on the model of EHHOP’s ancillary programs, we have helped other clinics form social service consult teams and refine medication acquisition.

Case Examples

While ECG maintains a uniform approach to our initial engagement and follow-up assessment with clients, the individual needs of SRFCs dictate a varying nature of the subsequent relationship. To illustrate this breadth, we present two case illustrations.

Case A: Guiding a New Clinic in the Selection of an Electronic Medical Record (EMR) System

Problem

lClient A had not yet opened when their partnership with ECG began. The clinic was looking for advice on finding a medical director, medication access and obtaining an appropriate EMR, among other needs common to newly developing clinics.

Solution

We administered an IAT and were able to stratify the clinic’s needs by importance and urgency. We determined that the most actionable concern was finding an electronic medical record system (EMR) that could be both functional and affordable. ECG consultants then used a number of resources to search for a suitable solution for Client A. In-house records and client logs were studied to see how the EMR systems at EHHOP and other client clinics were established. Consultants also spoke with members of the EHHOP Technology team and conducted independent research into EMR options geared towards nonprofits and free clinics. The primary EMR options, along with pros, cons, and links to further information, were organized into a guide written to help Client A consider their options. ECG also connected Client A with The National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics [11], an organization that provides EMR services to SRFCs by partnering with EMR companies. However, in the meantime, Client A was able to examine their choices, pick a temporary solution based on the resources presented and pending institutional approval, and will be able to select a permanent EMR. ECG continues to work with Client A to find customized solutions to their other goals.

Key lessons

This case illustrates the utility of ECG’s workflow in identifying the need of an individual clinic, and furthermore, leveraging our experience and expertise to provide an overview of potential solutions to a problem that many SRFCs face. ECG presented insights gathered from many other clinics which had gone through the same process in a compact, personalized guide. Eventually, ECG compiled these insights into a generalizable guide to EMRs for SRFCs, and later adapted this guide for dissemination as a presentation at the SSRFC National Meeting and inclusion in our online toolkit.

Case B: Creating a Patient Referrals System with an Established Clinic

Problem

Client B was an established clinic with a longitudinal care model. When the clinic approached ECG, they had just relocated 1 month prior to a new clinic location and were having difficulties with patient recruitment.

Despite having sufficient student and physician volunteers, the clinic was only filling approximately one half of their patient slots.

Solution

Given Client B’s geographical proximity to EHHOP, ECG consultants realized the unique opportunity to not only consult for Clinic B but establish a mutually beneficial collaboration. ECG consultants worked with Client B to develop an inter-clinic patient referral system between EHHOP and Client B. As EHHOP and Client B have different eligibility requirements in terms of insurance status and location residency, patients who are not eligible at one clinic are referred to the other clinic. Through a series of video conferences, ECG helped Client B establish a referrals protocol that was approved by the Executive Boards of both clinics, and patients have been successfully referred between the clinics.

Key lesson

This partnership exemplifies the potential benefits of consulting relationships between SRFCs and provides a prescription for collaboration that allows for mutual gains by each clinic as well as a larger impact on the communities served.

Online Toolkit

While ECG has the opportunity to work with approximately ten client clinics per year, this is only a small fraction of the estimated > 200 SRFCs in the USA [5]. However, clinics often face similar challenges in launching and sustaining their services. Broad information sharing of best practices by existing SRFCs could prove beneficial to the growing network of SRFCs that often operate independently and face multiple barriers to effective networking and leadership training. To this end, ECG has created a toolkit to launching and sustaining SRFCs for online publication [12]. The toolkit contains guides on several topics that will help SRFCs in all stages of development to maximize their impact on the communities they serve.

The guides were compiled using information from EHHOP, client clinics, and literature review, and they are published on a website for ease of access. The following guides are currently available: pharmacy, electronic medical record, transitioning student leadership, fundraising, and strategic planning. Several of the guides have accompanying templates to help steer clinics toward the best solutions for their specific goals and needs. The website also has a form for prospective client clinics to contact ECG to request consulting services. The toolkit has the potential to greatly benefit SRFCs across the nation by providing practical information and templates.

One limitation of the toolkit is that it may not include a solution that works for every clinic, and it likely will not include every possible solution. In order to create a guide on a particular topic, ECG student consultants attempt to become experts on the topic through a combination of clinic leader interviews as well as independent research and literature review. These guides always have the potential to be expanded and improved. By studying SRFC models, common needs, and potential solutions, ECG strives to primarily provide two contributions to the SRFC community: directly assisting client clinics to achieve their goals and sharing our experience with SRFCs across the country.

Conclusions

ECG’s mission is to serve as a sustainable source of support for the establishment, development, and advancement of SRFCs based on the needs unique to each community and limitations particular to each institution. ECG has capitalized on the 14 years of experience of EHHOP and aggregated best practices from interactions with 15 client SRFCs at medical schools across the USA. It has emerged as a uniquely valuable inter-clinic advising model, empowering SRFCs by providing tailored resources and multimodal consulting.

ECG has begun disseminating its findings through the online toolkit. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first collection of information on best practices for SRFCs, and it has the potential to increase the efficiency, productivity, and reach of SRFCs, allowing them to better serve vulnerable populations in the USA in need of quality healthcare.

The major limitation of the ECG online toolkit is that while the goal was to be broad and all encompassing, SRFCs have their own models and constraints in which they must operate, and the solutions are not one-size fits all. In addition, much of our expertise is derived from EHHOP’s model, and this is just one clinic. However, the online toolkit is intended to be a platform off which clinics can work; clinics that need further guidance can seek individualized consulting from ECG as a client clinic.

The ECG model, in which an experienced student group trained in organizational principles provides expert advice to similar groups extramurally, could be a fundamentally important method for student groups to share best practices for endeavors that impact a wide range of student initiatives, not limited to clinical practice. Examples include mental health outreach, anti-racism and bias training, and advocacy. These initiatives can address the social determinants of health underpinning many of the healthcare needs of underserved populations, thereby working synergistically with the clinical care provided by SRFCs. Student organizations that aim to become expert consultants should accrue a substantial wealth of knowledge of effective practices beyond their own organization. These organizations should consider partnering with outside organizations to initially train student leaders to become expert consultants and refine their mission and vision. By following ECG’s model and forming longitudinal consulting relationships, student organizations have the potential to promote impact and sustainability through the sharing of best practices that encompass more than just the experience of one institution.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Atran Foundation and the Mount Sinai Auxiliary Board for their generous support of EHHOP and ECG.

Funding

ECG receives funding from a grant from Atran Foundation, Inc.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Yasmin Meah is a Board member of the Society of Student Run Free Clinics (SSRFC).

Footnotes

Yash M. Maniar, Rohini Bahethi, Mackenzie Naert are co first Author

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- 2.Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The affordable care Act's impacts on access to insurance and health Care for low-Income Populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38(1):489–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Social Security Amendments of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89–97, 79 Stat. 286 (1965).

- 4.Garfield R, Orgera K, Damico A. The Coverage Gap: Uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2019.https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/. Accessed 27 Jun 2019.

- 5.Smith S, Thomas R, Cruz M, Griggs R, Moscato B, Ferrara A. Presence and characteristics of student-run free clinics in medical schools. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2407–2410. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creation of SSRFC. Society of Student Run Free Clinics. 2019. https://www.studentrunfreeclinics.org/about. Accessed 12 Nov 2019.

- 7.Atran Foundation. Foundation Directory Online. 2016. https://fconline.foundationcenter.org/fdo-grantmaker-profile/?key=ATRA001 ^. .

- 8.Social-Organizational Psychology Program. Teachers College, Columbia University. 2019. https://www.tc.columbia.edu/organization-and-leadership/social-organizational-psychology/. Accessed 19 Nov 2019.

- 9.Teoli D, An J. SWOT analysis. In: StatPearls [internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bjerke MB, Renger R. Being SMART about writing SMART objectives. Eval Program Plann. 2017;61:125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The National Association of Free and Charitable Clinics. 2016. https://www.nafcclinics.org/. .

- 12.SRFC Toolkit. EHHOP consulting group. 2019. http://consulting.eastharlemhealth.com/html/toolkit.html. Accessed 11 Nov 2019.