Abstract

Background

When the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) eliminated the oral segment of the board-certification examination, it began requiring in-training assessments termed Clinical Skill Evaluations (CSEs).

Objective

This study describes the experience of residency program directors (PDs) with CSEs and identifies opportunities for improvement.

Methods

A 23-question survey was administered electronically to neurology, child neurology, and psychiatry PDs assessing their CSE testing procedures in April 2019. Data from the ABPN preCERT® Credentialing System CSE was analyzed to corroborate the survey results.

Results

A total of 439 PDs were surveyed. The overall response rate was approximately 40% with a similar response across the 3 specialties. Overall, there was a strong enthusiasm for CSEs as they captured the essence of the physician–patient relationship. Most PDs encouraged trainees to attempt CSEs early in their training though the completion time frame varied by specialty. Approximately 57% of psychiatry residencies offered formal, in-person faculty training while less than one-fourth of neurology and child neurology programs offered such a program. Most PDs are interested in a faculty development course to ensure a standardized CSE testing process at their institution.

Conclusions

This survey confirmed earlier findings that CSEs are usually implemented early in the course of residency training and that most PDs think it captures the essence of the physician-patient relationship. While few residencies offer a CSE training course, there is widespread support for a formal approach to faculty development and this offers a specific opportunity for CSE improvement in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40670-020-00961-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Clinical skills, Faculty evaluation, Faculty development

Introduction

After much deliberation, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) phased out its oral (part II) certification examinations in its primary specialties of neurology, child neurology, and psychiatry and its subspecialty of child and adolescent psychiatry. These examinations included direct observation of candidate–patient interactions and focused on clinical reasoning and problem-solving. In order to assess these domains, the multiple-choice (part I) examination was redesigned, and a requirement for in-training assessment of clinical skills was instituted. The new requirement was termed Clinical Skill Evaluations (CSEs) and encompassed three domains: (1) the physician–patient relationship; (2) medical interview and examination; and (3) case presentation [1, 2]. The requirement became effective in 2005 for neurology and child neurology and 2008 for psychiatry. Psychiatry requires trainees to complete three individual CSEs whereas neurology and child neurology require residents to complete five CSEs.

The impetus for the change was multifold. The oral board examination was a high-stakes, artificial, and expensive encounter. In contrast, the CSEs could be completed during routine practice in a more realistic environment in which to perform a history and physical examination [3]. Given the numerous demands on faculty time, residents may have few supervised patient encounters during residency training [3, 4]. CSEs offer structured time with attendings and allow for more timely, directed feedback specifically in regard to how residents interact with patients and collect/interpret clinical data [5]. The ultimate hope was that early CSE implementation in training would allow for timely recognition of clinical deficiencies and remediation during training [1, 2].

The ABPN has been flexible in the implementation of the CSEs. The ABPN specifies that the passing standard is the level of performance acceptable for a board-certified, community practitioner, i.e., not the performance level considered acceptable at a given resident training level. The resident must obtain an acceptable score in each domain to pass the individual CSE. The ABPN also states the encounter must be observed by an ABPN-certified physician with a patient who is unknown to the trainee. The individual programs are able to select the patients, settings, and faculty for these assessments [1, 2]. The ABPN publishes a grading rubric but does allow programs to develop their own assessment tools [6, 7].

Most of the published research was conducted soon after CSEs were incorporated into residency training [8–12]. These studies highlighted concerns about the inter-rater reliability [8] along with differences in how the different specialties administered the CSEs [12]. Hence, this study was undertaken to determine if there has been an evolution in the administration of the CSEs and to identify opportunities for improvement. Our hypothesis, based on personal experience, is that PDs encourage early resident engagement in CSEs and that most trainees pass the CSE requirements on their first attempt. We also hypothesize that most programs do not offer a formal faculty CSE orientation, but that most PDs would be interested in such a forum. We also expect that the results and opinions would be similar across the specialties.

Methods

Study Population

This project was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. A total of 439 residency program directors (PDs) were identified from the ABPN’s PD mailing list which included all ACGME psychiatry (n = 220), neurology (n = 145), and child neurology PDs (n = 74) which minimized the response bias.

Survey Development

It was decided that a survey was the most appropriate tool to gather information from the national cohort of PDs. The web-based survey was created using Survey Monkey (San Mateo, CA, USA) to ensure a consistent and professional questionnaire that was available on multiple platforms [13].

The 23-question survey (Appendix 1) was newly developed using published, best practice guidelines and based on previous ABPN CSE questionnaires [12, 14–17]. The questionnaire focused on how programs fulfilled the CSE requirement, the number of attempts each resident required to pass CSEs, how faculty supervisors were selected, and opportunities to enhance the orientation of faculty supervisors. It was beta-tested on the web-based platform and validated for clarity and relevance by two PDs and the ABPN executive staff.

Survey Distribution and Response Rate

The survey was emailed in April 2019 with a cover sheet stating that the responses were voluntary and anonymous and would have no impact on the relationship with the ABPN. There were no incentives to complete the survey. The response rate (RR) was calculated using the American Association for Public Opinion Research Standard Definition RR5 [18] which defined the numerator as the number of completed surveys (partial responses were excluded) and the denominator as the total number of PDs contacted (220 psychiatry PDs, 145 neurology PDs, and 74 child neurology PDs). Our initial RRs according to each specialty were the following: psychiatry 32% (70/220), neurology 28% (40/145), and child neurology 27% (20/74). A second email reminder was sent to non-responders a week later with a total RR according to each specialty as follows: psychiatry 42% (92/220), neurology 37% (53/145), and child neurology 41% (30/74).

Data from the ABPN preCERT® Credentialing System was also analyzed. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentages) were used to summarize the survey results and the analysis was completed within Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

Results

Approximately 40% of PDs completed the survey with a similar RR across all specialties. The margin of error for the survey was 6% (95% confidence interval). The majority of the PDs previously completed the oral board examinations while few had served as ABPN oral board examiners (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of program directors

| PDs completed oral boards (%) | PDs previously ABPN oral examiner (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatry | 87% | 24 |

| Neurology | 66 | 13 |

| Child neurology | 66 | 3 |

PDs, program directors; ABPN, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology

CSE Administration

Most CSEs in neurology and child neurology were similarly administered during routine clinical practice. Psychiatry had a more diverse CSE administrative approach with 56% of CSEs conducted during routine clinical practice while 17% were conducted in specific clinical rotations or CSE designated testing days. A little less than 90% of all the PDs had little to no difficulty recruiting patients or faculty to participate in CSEs.

PDs from all three specialties recommended early administration of the CSEs in residency training. Results compiled from the ABPN preCERT® Credentialing System showed that about 50% of psychiatry residents completed their CSE requirement before PGY-3 (during PGY-1 or − 2) whereas neurology and child neurology trainees usually complete their CSEs after PGY-3 (Table 2). In neurology and child neurology, over 80% of PDs stated that over three-quarters of their residents passed the CSE requirement on their first attempt. Only 45% of psychiatry PDs thought their pass rate was that high while 34% thought the majority of residents did not pass the CSE requirement on their first attempt.

Table 2.

ABPN preCERT® Credentialing System Data: CSE completion rate by PGY level from 2014 to 2018

| PGY-1 (%) | PGY2 (%) | PGY3 (%) | PGY4 (%) | PGY5 (%) | Total applicants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatry | 12.8 | 37.6 | 30.5 | 17.9 | NA | 1487 |

| Neurology | 0.20 | 8.00 | 20.70 | 70.90 | NA | 685 |

| Child neurology | 0.0 | 0.3 | 8.9 | 22.6 | 61.4 | 119 |

ABPN, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology; CSE, clinical skills evaluations; PGY, postgraduate year

CSE Assessment

Since the ABPN does not specify how evaluators are selected outside of the requirement that they are ABPN-certified physicians, it is unclear what criteria programs/residents use to select faculty evaluators. There is a concern that residents may actively seek faculty members that they sense will offer an “easy passing grade”. In our survey, child neurology programs predominately selected faculty based on availability. Psychiatry and neurology PDs pre-selected faculty evaluators in 39% and 27% of the cases, respectively (Fig. 1). PDs thought about 10–20% of residents actively seek faculty members with a “perceived ‘easy’ approach to grading/feedback.” The inverse statement was less clear. Approximately 40% of PDs were unsure if residents avoided more stringent faculty, but 10–20% were convinced that residents avoided such clinicians.

Fig. 1.

How faculty are selected for CSE evaluations. Respondents could select more than one response. CSEs, clinical skill evaluations

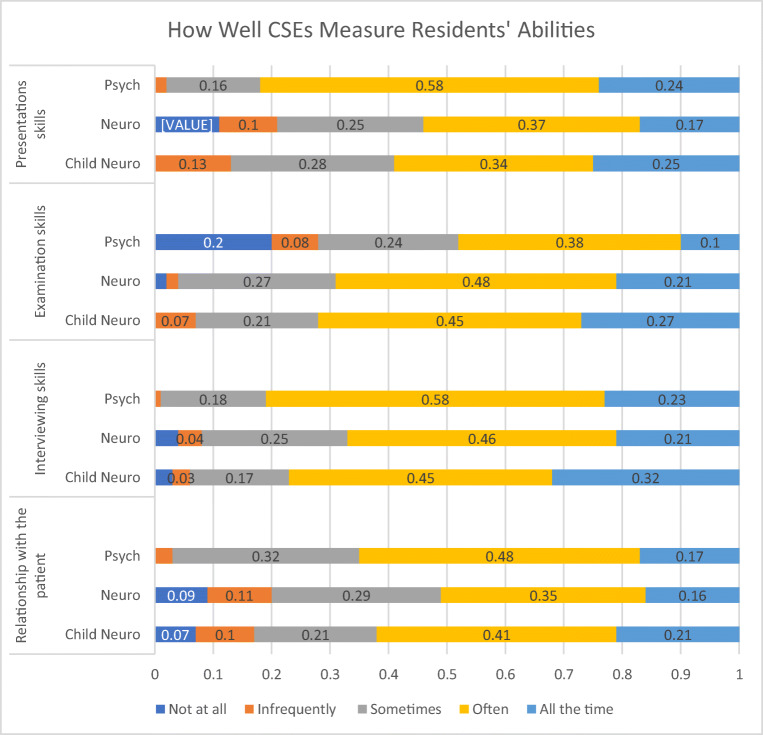

Approximately 40% of PDs were “somewhat confident” that their faculty members understood the pass/fail requirements of the examination. A little over 20% of neurology PDs had no confidence that their faculty members properly understood the grading criteria. Psychiatry PDs were more assured, as 60% stated that they were either “confident” or “extremely confident” their faculty members were aware of the ABPN grading criteria. Only 41% of neurology PDs and 46% of child neurology PDs made the same statement. PDs had a similar, favorable impression regarding the CSEs’ ability to measure the residents’ clinical and professional performance (Fig. 2). The most varied responses were on CSEs’ assessment of residents’ presentation and relationship with the patient which are both more subjective items when compared with grading a history or physical examination. Neurology and child neurology PDs stated CSEs “infrequently” or “never” accurately measured the humanistic physician–patient relation 20% and 17% of the time, respectively. Only 3% of psychiatry PDs made that same statement.

Fig. 2.

PDs’ perception of how well CSEs measured a resident’s clinical and professional abilities. CSEs, clinical skills evaluations; PDs, program directors

Future Opportunities

Almost 60% of psychiatry programs offered CSE faculty training. Only 25% of neurology and 14% of child neurology residencies offered such training. The vast majority of the training occurred in a live course with materials compiled from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) [19] and AADPRT websites [20]. A variety of factors were mentioned as possible barriers to implementing a training class but the overwhelming majority stated that a lack of time/resources was the major limiting factor. Only 10–25% of PDs thought CSE-related faculty development was unnecessary while 70–80% were interested in an ABPN-sponsored CSE faculty development course.

Discussion

This national survey of PDs compiled information about the ABPN CSE testing process while also investigating potential avenues for improvement. Since most of the previous work on this topic was completed soon after the CSEs were implemented, this study presents more recent data on how the testing process has evolved since its initiation.

In general, there was strong enthusiasm for CSEs which has been true since their inception [12]. PDs agreed that CSEs captured the essence of the medical interview, examination, and case presentation which is consistent with previous research [12]. The relatively strong RR in the era of survey fatigue and the considerable interest in a CSE faculty development program also highlight the investment in the program.

Psychiatry residency programs seem to have more infrastructure for CSEs when compared with their neurology counterparts which is different from our original hypothesis. Less than a quarter of neurology PDs offered CSE faculty training whereas a little over half of the psychiatry programs did so. Psychiatry PDs offered a variety of settings to complete the CSEs whereas neurology and child neurology usually conducted CSEs when time was available in routine clinical practice. Psychiatry faculty members also seemed more aware of the ABPN grading rubric though our survey suggests this is a global issue that spans all the specialties. The grading discrepancy has been a challenge since the CSEs were developed as most educators’ grade residents based on their level of training. It would typically be unfair to compare a PGY-1 resident with a more senior colleague in the typical clinical environment. The CSE grading scale which specifically sets the level of performance at a board-certified, community practitioner requires an effortful mindset change. Recommending that residents complete these assessments later in their training while also reinforcing the grading criteria to faculty members would help alleviate this specific concern.

The reasons underlying the differences between psychiatry and neurology are likely multifaceted. One possible explanation is that the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) quickly implemented a CSE faculty development course which was hosted at its national meeting and posted a number of resources on its website. This early adoption of CSE in psychiatry has been illustrated previously. In a 2012 survey, psychiatry residents were more likely to participate in program designated CSE days and receive more detailed feedback from their faculty [12]. The consortium of neurology program directors has not adopted this approach though the AAN does have online CSE training modules [19].

It is unclear if faculty orientation improved CSE administration and there has been limited research into this topic. The survey results reported here suggest there is some value to such training. As new faculty members join the CSE process, there is also a concern that they will administer the CSEs with less rigor compared with faculty members who participated in the oral board examinations [8]. Most of the PDs in our study participated in the oral board examinations as examinees, but few served as official ABPN examiners. Further studies will be needed to determine how the CSE protocols change as we move further from the oral board examination and the examiner orientation that it provided.

There is a strong interest in an ABPN-sponsored training module from both PDs who currently host faculty CSE training and those PDs that do not. The current CSE training curricula include curated materials from the professional societies [19, 20]. These modules focus on inter-rater reliability and review the ABPN’s grading guidelines. Both emphasize that the ABPN’s acceptable performance is defined as a “competent practicing psychiatrist or neurologist” and is not relative to the level of training. This approach may be counter to how most faculty approach resident assessment.

Our original hypothesis stated that most PDs recommended early participation in CSEs. This seemed to be the case with psychiatry residents completing CSEs earlier than the neurology trainees. The ABPN preCERT® data showed that most psychiatry residents completed their CSE requirement before PGY-3 whereas neurology and child neurology trainees usually finished CSEs after PGY-3. This divergence could be due to the fact that neurologists and child neurologists must complete five patient-specific CSEs whereas psychiatrists only need to complete three unspecified CSEs.

The initial CSE pass rate also varied across the specialties. Our initial hypothesis was that the pass rate would be similar across specialties, but over 80% neurology and child neurology PDs thought the majority of their residents passed the CSEs on their first attempt. This contrasted with psychiatry where only 45% of PDs thought their initial pass rate was that high. This is consistent with a previous CSE survey in 2013 [12]. The reason for the disparity is unclear. It may be related to the fact that most psychiatry residents are attempting CSEs earlier in training when compared with neurology residents. Psychiatry may also have a lower pass rate to indirectly encourage more observed encounters with feedback.

Though our study specifically focused on three specialties, our findings are more broadly applicable. Many medical boards are transitioning from oral board examinations. The ABPN’s specific evolution can serve as a model for others to follow and hopefully improve upon. The ABPN was deliberate in their flexible assessment/grading protocols for CSEs. This allowed programs to develop specific templates that fit their institutions. That same flexibility also accounts for the variability we see within neurology, child neurology, and psychiatry programs. Other boards should be aware of this trade-off and develop specific interventions to address potential variations. Lastly, any large-scale programs such as clinical assessments require constant monitoring and evaluation making projects like this one important throughout the lifecycle of any curriculum.

Our study has several limitations. First and foremost is the responder bias as this survey was completely voluntary. It is possible that PDs with more of an interest in the CSEs may have been more likely to respond. Since no identifying information was collected, we cannot determine if the program characteristics influenced the results. The relatively low RR may also limit the generalizability of our report.

Conclusion

Further research is needed not only on CSE administration but on effective CSE faculty training. This research should be geared towards improving interrater reliability while also determining the long-term effects of CSEs on residency education. The fact that PDs are invested in CSEs offers a strong platform to move the examination forward.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 16 kb)

Author Contributions

Justin R. Abbatemarco contributed to design, literature search, acquisition and analysis of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing/review.

Dorthea Juul contributed to design, analysis of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing/review.

Patti Vondrak contributed to the design, analysis of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing/review.

Mary Ann Mays contributed to the design, analysis of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing/review.

Mary A. Willis contributed to the design, analysis of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing/review.

Larry R. Faulkner contributed to the design, literature search, acquisition of data, analysis of data, manuscript preparation, and manuscript editing/review.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This project was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This study/data/abstract has not been presented. This paper has not been published online or in print and is not under consideration elsewhere.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.ABPN. Requirements for clinical skills evaluation in neurology and child neurology 2017 [updated November 2017. Available from: https://www.abpn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/CSE-Neurology-2017.pdf.

- 2.ABPN. Requirements for clinical skills evaluation in psychiatry 2017 [updated November 2017. Available from: https://www.abpn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/CSE-Psychiatry-2017.pdf.

- 3.Holmboe ES. Faculty and the observation of trainees’ clinical skills: problems and opportunities. Acad Med. 2004;79(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmboe ES, Hawkins RE, Huot SJ. Effects of training in direct observation of medical residents' clinical competence: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(11):874–881. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-11-200406010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daelmans HE, Overmeer RM, van der Hem-Stokroos HH, Scherpbier AJ, Stehouwer CD, van der Vleuten CP. In-training assessment: qualitative study of effects on supervision and feedback in an undergraduate clinical rotation. Med Educ. 2006;40(1):51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurology Clinical Evaluation Exercise2015:[1–2 pp.]. Available from: https://www.abpn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ABPN_NEX_form_v2.pdf.

- 7.2015 Psychiatry Clinical Skills Evaluation Form; (1):[1–2 pp.]. Available from: https://www.abpn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ABPN_CSV_form_v1.pdf.

- 8.Schuh LA, London Z, Neel R, Brock C, Kissela BM, Schultz L, Gelb DJ. Education research: Bias and poor interrater reliability in evaluating the neurology clinical skills examination. Neurology. 2009;73(11):904–908. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b35212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jibson MD, Broquet KE, Anzia JM, Beresin EV, Hunt JI, Kaye D, Rao NR, Rostain AL, Sexson SB, Summers RF, ABPN Task Force on Clinical Skills Verification Rater Training. Clinical skills verification in general psychiatry: recommendations of the ABPN Task Force on Rater Training. Acad Psychiatry 2012;36(5):363–368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dalack GW, Jibson MD. Clinical skills verification, formative feedback, and psychiatry residency trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(2):122–125. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.09110207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao NR, Kodali R, Mian A, Ramtekkar U, Kamarajan C, Jibson MD. Psychiatric residents’ attitudes toward and experiences with the clinical-skills verification process: a pilot study on U.S. and international medical graduates. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(4):316–322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.11030051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juul D, Brooks BA, Jozefowicz R, Jibson M, Faulkner L. Clinical skills assessment: the effects of moving certification requirements into neurology, child neurology, and psychiatry residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):98–100. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00265.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips AW, Reddy S, Durning SJ. Improving response rates and evaluating nonresponse bias in surveys: AMEE Guide No. 102. Med Teach. 2016;38(3):217–228. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1105945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ABPN. ABPN Education and Research Initiatives. [updated November 2018. Available from https://www.abpn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ABPN-Education-and-Research-Initiatives.pdf

- 15.Artino AR, Jr, Gehlbach H, Durning SJ. AM last page: avoiding five common pitfalls of survey design. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1327. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822f77cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artino AR, Jr, La Rochelle JS, Dezee KJ, Gehlbach H. Developing questionnaires for educational research: AMEE guide no. 87. Med Teach. 2014;36(6):463–474. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.889814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys : the tailored design method. 4th edition. ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2014. xvii, 509 pages p.

- 18.Definitions S. Final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys: American Association for Public Opinion Research; 2016.

- 19.American Academy of Neurology. AAN Clinical Skills Examination Training Module: American Academy of Neurology; 2012 [Available from: https://www.aan.com/tools-and-resources/academic-neurologists-researchers/program-and-fellowship-director-resources/program-director-resources/.

- 20.American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training. Virtual Training Office [Available from: https://www.aadprt.org/training-directors/virtual-training-office.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 16 kb)