Abstract

We studied how students in a Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) program perceived the importance of critical thinking and the extent to which critical thinking was perceived to be included in each of 25 courses of the first-year curriculum at The University of Texas School of Dentistry at Houston (UTSD). Sixty-nine of the 102 second-year students who were invited participated in an online survey. The survey had three parts, with all statements of each part evaluated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The first two parts assessed the importance of critical thinking in dental education and the criteria by which critical thinking in didactic curriculum can be measured. In the third part of the survey, students evaluated how well each course of the first-year curriculum achieved critical thinking. More than 90% of the respondents strongly agreed/agreed that critical thinking is essential to making clinical decisions. Students strongly agreed/agreed that 19 of 25 of the courses incorporated critical thinking. However, when students were asked to rank the top five of the 25 courses, only two courses (Human Biology, Neuroscience) emerged above all others in their weighted ranks, with another seven courses standing out, leaving 16 courses with low weighted rankings for their inclusion of critical thinking. In summary, students agreed on the importance of critical thinking in dental education, and on the criteria by which the incorporation of critical thinking should be measured in didactic and pre-clinical courses.

Keywords: Critical thinking, Dental curriculum, Student perception

Introduction

Critical thinking, commonly referred to as rational, logical thought, is a rich concept with its roots in philosophy and dating back to Socrates [1]. Critical thinkers exhibit contextual perspective, creativity, inquisitiveness, confidence, and better problem-solving skills [2].

Critical thinking is emphasized in dental education of North America. In fact, one of the standards for the accreditation of dental schools is the measurement of critical thinking in students [3]. More recently, the concept has gained heightened attention due to the introduction of the integrated national dental board examination (INBDE). Dental curricula have increasingly reflected that students should understand concepts, as opposed to rote memorization of facts or procedural algorithms. It is for this reason that many dental schools have adopted alternative teaching and learning strategies that foster critical thinking by challenging students to become self-directed learners who continuously seek evidence for clinical decision-making [4, 5]. Accordingly, in 2012, The University of Texas School of Dentistry at Houston (UTSD) underwent curricular reform to foster critical thinking at the grassroot levels by dental students in their first year, which would then promote better decision-making later when in practice. Nevertheless, despite being a ubiquitous term in all first-year syllabi at UTSD, there is a lack of conceptual clarity as to what it means to “think critically” and how best to achieve it in a classroom.

Experts have defined critical thinking in many ways over the decades, a review of which reveals a wide range of focus and perspective, as detailed in the following examples. The most widely accepted definition of critical thinking by Watson and Glaser is that it is “the synthesis of attitudes, knowledge, and skills” [6]. Scriven and Paul have described critical thinking as “the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information…” [7]. Kurland suggests that critical thinking “is concerned with reason, intellectual honesty, and open-mindedness as opposed to emotionalism, intellectual laziness, and closed-mindedness” [8]. The American Philosophical Association defines critical thinking as “the process of purposeful, self-regulatory judgment. . . reasoned consideration to evidence, context, conceptualizations, methods, and criteria” [9].

While the faculty of UTSD fully embrace teaching critical thinking skills as an essential part of the curriculum, an ongoing challenge is identifying the best pedagogy to facilitate students improving their critical thinking skills, particularly given the great variability in definitions of critical thinking. Faculty incorporate critical thinking into their courses with various definitions in mind, and thus employ different methods and curricular approaches to foster critical thinking. This begs the question, how do students perceive critical thinking? Most students are not directly taught critical thinking, but are expected to display it as a skill through assignments and assessments. Yet, little attention has been focused on student perceptions of their development as critical thinkers in the DDS curriculum. In this study, we aimed to help fill this void by examining the following specific goals: (1) identify how DDS students at UTSD perceive the importance of critical thinking in the first-year curriculum, (2) evaluate how students perceive the key characteristics of a curriculum that includes critical thinking, and (3) assess the degree of incorporation of critical thinking in first-year curriculum as perceived by students at UTSD.

Methods

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston was received on August 8, 2017 (HSC-DB-17-0710), with designation of exempt status. One hundred and two second-year dental students from the class of 2020 who took first-year dental courses during the 2016–2017 academic year were emailed invitations to participate in an optional online survey (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah) during the time period September 18–October 6, 2017. In total, 69 of the 102 students responded to the survey.

The survey was divided into three parts, A, B, and C (which had two subcomponents) (Table 1). Parts A and B utilized a five-point Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. Part A contained statements on the importance of critical thinking in dental education. Part B contained statements on the criteria by which critical thinking in didactic curriculum can be measured. In part C, students were asked to utilize a Likert scale to measure how well each of 25 courses in the first-year curriculum achieved critical thinking, and then to rank the top five courses that best utilized critical thinking in the course. Responses to parts A, B, and C were summarized with mean and 95% confidence intervals for each statement. The second portion of part C is reported using weighted ranks given the number of respondents per course. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (R Core Team 2017) [10].

Table 1.

The survey that was administered to the students

| A. The following are statements regarding the objectives of critical thinking in a dental education curriculum. To what degree do you agree with each statement? Please rate the following statements based on a scale of “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree” | |||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| 1. Critical thinking is an essential part of being able to accurately diagnose conditions, advise patients, and integrate new dental developments and discoveries into patient care | |||||

| 2. Critical thinking is imperative to teach so that students have the skills to become confident in a clinical setting | |||||

| 3. Health care professionals must make decisions that affect patient outcomes, therefore, the ability to think well in the process of making sound clinical decisions ought to be given high priority | |||||

| 4. The best way to produce students confident in clinical decision-making is through a curriculum that emphasizes critical thinking in didactic courses | |||||

| 5. Because health care is a dynamic field, education needs to instill critical thinking skills in students | |||||

| B. The following are statements regarding the criterion by which critical thinking in didactic curriculum can be measured. To what degree do you agree with each statement? Please rate the following statements based on a scale of “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree” | |||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| 1. Critical thinking should assess a student’s skills and abilities in analyzing, synthesizing, applying, and evaluating information | |||||

| 2. Critical thinking questions can require the application of knowledge from disciplines | |||||

| 3. Critical thinking questions on an assessment should make clear how interconnected taught material is | |||||

| 4. Critical thinking and how it is applied to a course should have clear concepts and well-articulated goals, criteria, and standards | |||||

| 5. Critical thinking should test for thinking that promotes the active engagement of students in constructing their own knowledge and understanding | |||||

| C. Considering the objectives and criterion for critical thinking, do you think that the following courses in your first-year dental curriculum significantly incorporate critical thinking? Please rate the following statements based on a scale of “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree” | |||||

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

| 1. Neurosciences (DENF1504) | |||||

| 2. Biomedical Science Core (DENF1510) | |||||

| 3. Oral Biology (DENF1511) | |||||

| 4. Head and Neck Anatomy (DENS1512) | |||||

| 5. Human Biology (DENS1513) | |||||

| 6. Oral Biology II (DENS1514) | |||||

| 7. Clinical Applications I (DENF1543) | |||||

| 8. Clinical Applications II (DENS1544) | |||||

| 9. Principles of Pharmacology (DENU1561) | |||||

| 10. Local Anesthesia (DENU1562) | |||||

| 11. Dental Anatomy I (DENF1601) | |||||

| 12. Dental Anatomy Lab I (DEPF1602) | |||||

| 13. Dental Anatomy Lab II: Occlusion (DEPS1604) | |||||

| 14. Operative Dentistry I (DEPS1614) | |||||

| 15. Ethics in Dentistry (DENF1621) | |||||

| 16. Foundational Skills for Clinic I (DENF1651) | |||||

| 17. Foundational Skills for Clinic II (DENS1652) | |||||

| 18. Biomaterials I (DENS1672) | |||||

| 19. Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology I (DENU1703) | |||||

| 20. Introduction to Clinic (DENU1704) | |||||

| 21. Perio I: Diagnosis & Treatment Planning (DENU1721) | |||||

| 22. Basic & Applied Nutrition (DENF1931) | |||||

| 23. Prevention of Oral Diseases (DENF1934) | |||||

| 24. Introduction to Dental Informatics (DENF1991) | |||||

| 25. Dental Practice Readiness Curriculum (DPRC1624) | |||||

|

26. From the following, rank the top five courses that significantly incorporate critical thinking. Neurosciences (DENF1504) Biomedical Science Core (DENF1510) Oral Biology (DENF1511) Head and Neck Anatomy (DENS1512) Human Biology (DENS1513) Oral Biology II (DENS1514) Clinical Applications I (DENF 1543) Clinical Applications II (DENS 1544) Principles of Pharmacology (DENU1561) Local Anesthesia (DENU1562) Dental Anatomy I (DENF1601) Dental Anatomy Lab I (DEPF1602) Dental Anatomy Lab II: Occlusion (DEPS1604) Operative Dentistry I (DEPS1614) Ethics in Dentistry (DENF1621) Foundational Skills for Clinic I (DENF1651) Foundational Skills for Clinic II (DENS1652) Biomaterials I (DENS1672) Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology I (DENU1703) Introduction to Clinic (DENU1704) Perio I: Diagnosis & Treatment Planning (DENU1721) Basic & Applied Nutrition (DENF1931) Prevention of Oral Diseases (DENF1934) Introduction to Dental Informatics (DENF1991) Dental Practice Readiness Curriculum (DPRC1624) |

|||||

Results

In part A of the survey (statements A01–A05; Fig. 1) on the objectives of critical thinking, students consistently strongly agreed and agreed with the objective that critical thinking is fundamental to the curriculum. We found that 97.2% of the respondents strongly agreed or agreed that critical thinking is important in making correct diagnosis, providing patient care, and making sound clinical decisions. The statement, “the best way to produce students confident in clinical decision making is through a curriculum that emphasizes critical thinking in didactic courses” (A04), had the most variability in student responses (43.06% strongly agreed, 43.06% agreed, 8.33% neutral, 5.56% disagreed). This indicates uncertainty among students that the best way to produce students with confidence is through a curriculum that emphasizes critical thinking.

Fig. 1.

Results of parts A and B of the survey on the importance of critical thinking in dental education and the key characteristics of a curriculum that includes critical thinking, respectively. Shown are means and 95% confidence intervals of the responses to each statement

In part B of the survey (statements B01–B05; Fig. 1), students were asked to evaluate the criteria for critical thinking. The definitions we chose for this study focused on interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation. As with part A, 94% of students strongly agreed or agreed with the definitions provided among the five statements. There was little deviation in student responses among the statements.

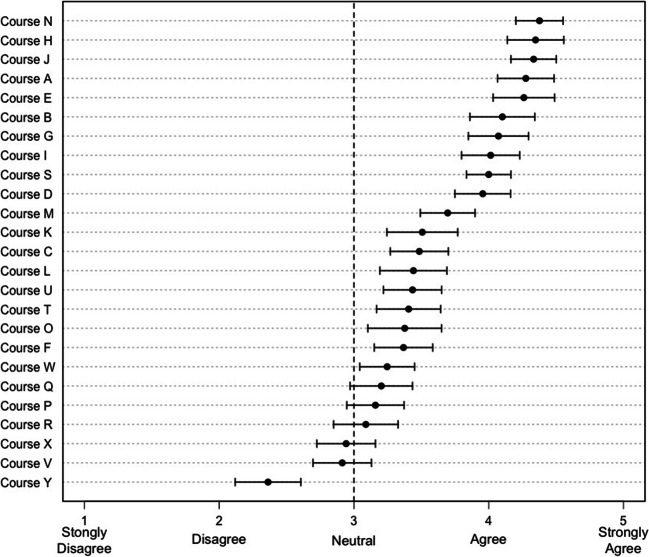

In part C, students evaluated the extent to which critical thinking was utilized in each of their 25 courses in the first-year curriculum (Fig. 2) from strongly agree at the top to lower levels of agreement toward the bottom. Course titles have been removed to maintain anonymity. As can be seen from this analysis, overall students agreed that almost all courses included critical thinking, as shown by all values being to the right of the dotted neutral line. However, there was a handful of courses that tended to be perceived as neutral in their inclusion of critical thinking, noted toward the bottom of Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Results of part C, statements 1–25, on how well each course in the first-year curriculum incorporated critical thinking. Shown are means and 95% confidence intervals of the responses for each course

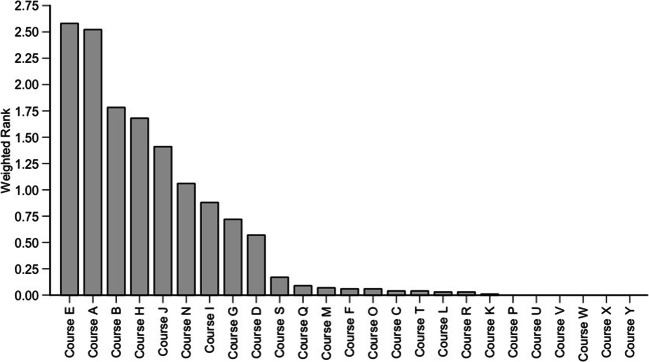

A slightly more nuanced assessment of the inclusion of critical thinking in courses was obtained from students by asking them to rank their top five courses, weighted ranks of which are shown in Fig. 3. In this way, not all courses can be chosen by each student, such that a pattern emerges among students in their selection of particular courses. With this weighted rank approach, only two courses (Human Biology and Neuroscience, identified in no particular ranking) emerged among all courses in having strong weighted ranks. An additional seven courses stood out positively in their rankings for inclusion of critical thinking (Clinical Applications I, Clinical Applications II, Biomedical Sciences Core, Local Anesthesia, Head and Neck Anatomy, Operative Dentistry I, and Principles of Pharmacology, identified in no particular ranking), thus leaving 16 courses with very low weighted rankings in not having included critical thinking. The top courses in Fig. 3 correspond with the first 8 and the tenth course listed in Fig. 2. However, Fig. 3 conveys that not all courses are equal, when students are limited to only select five among the 25 as most effective in including critical thinking. If all courses were positively viewed in their inclusion in critical thinking, as may be potentially considered interpretation of Fig. 2, then in Fig. 3, there would be a roughly equal and positive weighted rank across all courses.

Fig. 3.

Results of part C, statement 26, on ranking of the top 5 courses that incorporated critical thinking in the first-year curriculum at UTSD. Shown are weighted ranks (based on number of respondents) for each course

Discussion

We examined the perception of second-year dental students at UTSD to their first-year curriculum with regard to the inclusion of and degree of critical thinking. Results show that overall students’ perception was positive, students believed critical thinking to be essential to dental education and critical thinking skills needed to be supported and challenged to develop as critical thinkers. However, not all courses did so equally.

Of the five statements in part A, only one—statement 4—contained an absolute which stated “the best way to produce students confident in clinical decision making is through a curriculum that emphasizes critical thinking in didactic courses.” This statement had the lowest degree of agreement. This suggests that, although students find critical thinking to be important, there may be other educational methods better suited to produce competent clinicians. Alternatively, it is feasible that students believed that critical thinking cannot be taught. Coles and Robinson showed that critical thinking can be fostered through teaching if the teaching activity specifically and deliberately aims to develop thinking strategies by providing encouragement, opportunities, and guided practice involving principles and techniques [11]. Likewise, De Bono suggested that critical thinking skills do not develop as a by-product of subject-learning or teaching the obvious, but instead requires appropriate instruction of meaningful content [12].

In part B, we utilized statements that defined critical thinking as a process that utilizes interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation. Student responses supported that students see critical thinking as a process, which utilizes interpretation, analysis, and evaluation. Although it is well established that interdisciplinary approaches encourage students to perceive the connections between seemingly unrelated domains, thereby facilitating a personalized process of organizing knowledge and facilitating critical thinking [13, 14], the statement which students least agreed with was “critical thinking questions can require the application of knowledge from multiple disciplines” indicating the reasonable perspective that critical thinking is different from interdisciplinary thinking.

In statements 1–25 of part C, students were asked to use the Likert scale to evaluate the degree to which critical thinking was incorporated into each class taken during the first year of dental school. In statement 26 of part C, students were asked to rank the five courses they felt best incorporated critical thinking into the curriculum. Collectively, three groups of courses emerged based on student responses: group 1 being the two highest ranked courses (Human Biology and Neuroscience), group 2 being seven courses that stood out from the rest for inclusion of critical thinking (Clinical Applications I, Clinical Applications II, Biomedical Sciences Core, Local Anesthesia, Head and Neck Anatomy, Operative Dentistry I, and Principles of Pharmacology) and group 3 being the last 16 courses that were considered low for critical thinking. Most courses in the first-year curriculum are didactic courses, except Clinical Applications I and II, which are problem/case-based learning (PBL) courses. Clinical Applications I and II are offered in the fall and spring semesters, respectively, and require students to apply the material presented in didactic courses running parallel to them in clinical scenarios. Clinical Applications I introduces students to the basics of evidence-based dentistry, performing literature searches, and creating weekly presentations. Unlike Clinical Applications I in which the topic changes each week, in Clinical Applications II students are presented with a patient for each system, and the case lasts for the entire length of the system being taught in Human Biology. Students then develop learning issues about the case and are required to research these in the literature and present them to the group and facilitator at the next session. This process continues for each session until completion of the case.

Biomedical Sciences Core and Human Biology, although didactic courses, are courses in which various basic science disciplines are integrated horizontally. For example, Human Biology is system-based and integrates physiology, anatomy, and histology. The integrated nature of Human Biology course renders the potential for incorporation of critical thinking. It is also possible that the students ranked the courses in part C based on their level of difficulty, i.e., based on how much critical thinking was necessary just to understand the concepts. For example, neuroscience and physiology are inherently challenging subjects and therefore it is perhaps likely that students correlated difficulty level of the subject area to degree of critical thinking.

It is encouraging that students considered Clinical Applications I and II to utilize critical thinking as these courses were specifically designed to be critical thinking courses where teaching would be primarily driven by student inquisition and discovery. This indicates that course designers at UTSD and students’ views on critical thinking align. However, given that these courses were specifically introduced with the goal of integrating biomedical and clinical sciences and fostering critical thinking, ideally, these courses should have been ranked the highest for incorporating critical thinking. The lack thereof suggests that there is room for improvement in the design of these courses.

For PBL to achieve its educational goals, it must be implemented effectively [15]. Pedagogically, our result may indicate that the cases need to be optimized such that to provide better connection between content and application, and/or the faculty facilitators need to guide the students toward making their own connections through challenge, feedback, and engaging discussions. The observed ranking for problem-based courses might also be a reflection of the frequency and duration at which the courses are implemented in our program, which is only biweekly for a total of 3–4 h, whereas conventionally problem-based courses meet in two 3-h blocks per week, sometimes utilizing even 10 h per week [15–18]. Authors identify faculty development and training on PBL pedagogy, training and development of faculty as effective PBL facilitators and provision of resources such as sufficient time as important factors in successful implementation of PBL and fostering critical thinking through such courses.

Courses which students felt neutral about their incorporation of critical thinking included mainly one credit hour and/or online courses. This could indicate that students feel interaction in a classroom setting is more conducive to creating an environment for nurturing critical thinking. Studies have shown that with online courses, design of the course has a significant impact on whether students approached learning in a deep and meaningful manner, fostering critical thinking [19]. This requires faculty training and support in the delivery of quality online courses. Many researchers posit that instructors play a different role from that of traditional classroom instructors when they teach online courses [20, 21].

Dental school assessments aim to foster the development of higher-order thinking skills to support a foundation of knowledge and its application to clinical reasoning [22, 23]. Interestingly, of the courses ranked as top nine for incorporating critical thinking, all except Clinical Applications I and II primarily rely on multiple choice questions (MCQs) as their assessment method. Our results therefore indicate that well-written MCQs can support learner engagement in higher levels of cognitive reasoning, such as application or synthesis of knowledge. Therefore, the authors recommend that in the event summative assessments such as MCQs are used, the questions should be written to measure higher-order thinking, rather than an examinee’s ability to simply recall factual information, and that the faculty apply the cognitive domains of Bloom’s taxonomy when creating MCQs. However, it is imperative to note that engaging students in multiple assessment methods, both summative and formative, is essential to accurately and reliably measure critical thinking.

It should be acknowledged that this pilot study was a single cohort study. Only the class of 2020 was surveyed for their perception on critical thinking and therefore the generalizability of our results may be limited by the single-centered nature of the study. Despite the small sample size, clear themes emerged from the results that were sufficient for this exploratory investigation. We hope to repeat iterations of this survey to multiple classes as they matriculate their first-year curriculum in order to enhance the richness and generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

Overall, students in this study perceived critical thinking to be important in dental education and identified that some courses incorporated critical thinking better than others in the first-year DDS curriculum at UTSD; however, more critical thinking components may need to be added to some courses in the first-year curriculum.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Valenza (Dean, UTSD) for his insightful feedback on our manuscript. We thank Mr. Patrick Finnerty for providing assistance with administering the survey on Qualtrics.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Institutional Review Board, HSC-DB-17-0710) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Paul R, Elder L, Bartell T. Taken from the California teacher preparation for instruction in critical thinking: research findings and policy recommendations. Sacramento: State of California, California Commission on Teacher Credentialing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facione PA. Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (Research Report). Millbrae: The California Academic Press. 1990.

- 3.Accreditation Standards for Dental Education Programs. Commission on Dental Accreditation. Commission on Dental Education. 2019.

- 4.Elangovan S, Venugopalan SR, Srinivasan S, Karimbux NY, Weistroffer P, Allareddy V. Integration of basic-clinical sciences, PBL, CBL, and IPE in U.S. dental schools’ curricula and a proposed integrated curriculum model for the future. J Dent Educ. 2016;80:281–290. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2016.80.3.tb06083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duong MT, Cothron AE, Lawson NC, Doherty EH. U.S. dental schools’ preparation for the integrated national board dental examination. J Dent Educ. 2018;82:252–259. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson G, Glaser EM. Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal manual. Kent: The Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scriven M, Paul R. Defining critical thinking. Retrieved from: https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/defining-critical-thinking/766. Accessed 12 August 2019.

- 8.Kurland D. How the language really works: the fundamentals of critical reading and effective writing. www.criticalreading.com: http://www.criticalreading.com/critical_thinking.htm. Accessed 12 August 2019.

- 9.American Philosophical Association. Critical thinking: a statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. ERIC document, ED. 1990:315–423.

- 10.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coles MJ, Robinson WD. Teaching thinking: what is it? Is it possible? In: Coles MJ, Robinson WD, editors. Teaching thinking: a survey of programmes in education. Bristol: Bristol Press; 1989. pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Bono E. Teaching thinking. Harmondsworth: Pelican Books; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivanitskaya L, Clark D, Montgomery G, Primeau R. Interdisciplinary learning: process and outcomes. Innov High Educ. 2002;27:95–111.

- 14.Walsh LJ, Seymour GJ. Dental education in Queensland: II. Principles of curriculum design. SADJ. 2001;56:140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdelkarim A, Schween D, Ford T. Implementation of problem-based learning by faculty members at 12 U.S. medical and dental schools. JDE. 2016;80:1301–1307. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2016.80.11.tb06215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholl TA, Lou K. A model for small-group problem-based learning in a large class facilitated by one instructor. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76:117. doi: 10.5688/ajpe766117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman K, Hosokawa M, Blake R, Headrick L, Johnson G. Problem-based learning outcomes: ten years of experience at the University of Missouri—Columbia School of Medicine. Acad Med. 2006;81:617–625. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232411.97399.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubin B. Innovative curriculum prepares medical students for a lifetime of learning and patient care. Mo Med. 2016;113:170–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrison DR, Cleveland-Innes M. Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: interaction is not enough. Am J Dist Educ. 2005;19:133–148. doi: 10.1207/s15389286ajde1903_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, McGrath D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education—an integrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:130. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wingard RG. Classroom teaching changes in web-enhanced courses: a multi-institutional study. Educ Q. 2004;27:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnsen DC, Lipp MJ, Finkelstein MW, Cunningham-Ford MA. Guiding dental student learning and assessing performance in critical thinking with analysis of emerging strategies. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:1548–1558. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2012.76.12.tb05418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnsen DC, Finkelstein MW, Marshall TA, Chalkley YM. A model for critical thinking measurement of dental student performance. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:177–183. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2009.73.2.tb04652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]