Abstract

There are increasing calls to graduate physicians with a strong understanding of health systems science (HSS). Many schools have incorporated didactics on health systems science content such as quality improvement, patient safety, or interprofessional education. Creating a systems-ready physician requires more than teaching content in classroom settings. Using Miller’s pyramid of assessment of clinical performance, we have developed strategies to move our learners from the cognitive-based “knows” level to the behavior-based “does” level of understanding of the HSS competencies. Our medical students begin learning HSS in classroom settings. Next, the students apply this knowledge during their core clerkships. This gives them an opportunity to get feedback increasingly from high-fidelity clinical settings.

We embedded assessment strategies and tools in the clerkship year to facilitate the demonstration, observation, and assessment of HSS competencies in the setting of our core clerkships. We also have students self-assess their competence in our graduation competencies at the end of each year. Student self-assessment from the beginning of the clerkship year to the end showed significant increases in the HSS competencies. Our clerkship student assessment data from our first cohort suggest that faculty had difficulty observing and assessing some of the competencies unique to health systems science. The clerkships have developed multiple projects and assignments to allow students to demonstrate HSS competencies. Faculty and resident training to prompt, observe, and assess these competencies is ongoing to close the assessment gap. In the area of professionalism, student self-assessment and faculty clinical assessment correlate strongly.

Keywords: Health systems science, Systems-ready physician, Leadership, Medical education, Undergraduate medical education, Health care, Clinical clerkships

Introduction

The increasing challenges that our health care system faces, with fragmented, inefficient, and expensive care which fails to consistently deliver desirable patient care outcomes, highlight the importance of a good understanding of health systems sciences by all clinicians who operate within this system.

The medical school mission has historically been composed of the two pillars of basic and clinical sciences. Since the American Medical Association’s original call for Accelerating Change in Medical Education in 2013 [1], conversations about health systems science (HSS) as a new, third curricular leg have been ongoing. Gonzalo et al. described a sophisticated health systems science curricular framework in undergraduate medical education, which included six core domains (health care structures and processes; health care policy, economics, and management; clinical informatics and health information technology; population and public health; value-based care; health system improvement), five cross-cutting domains (leadership and change agency; teamwork and interprofessional education; evidence-based medicine and practice; professionalism and ethics; scholarship), and a linking domain (systems thinking) [2].

Multiple challenges to implementing an effective HSS curriculum have been described, including the current culture of medical education and clinical systems which do not support systems education, as well as the misconception that systems concepts are “important but not essential,” and that students lack sufficient knowledge and skills to participate in and perform systems roles [3]. Schools have approached this new curriculum with a variety of strategies, but most continue to relegate HSS content to didactics or case-based learning [4]. Integration of such a curriculum, and its assessment, is particularly challenging in the busy clinical setting of the clerkship rotations. There is a need to “transform the relationship between medical schools and health systems.” [5]. Creating a “systems-ready physician” requires more than passive learning. It requires opportunities to practice and apply these skills, with the addition of value-added systems roles for medical students [6], creating a win-win situation, where patient care is improved and, concurrently, student education is enhanced, with the student becoming a truly integral part of the care team [7, 8].

Miller’s pyramid of assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance [9] describes the graduated approach of progressing from the cognitive-based “Knows,” eventually to the behavioral-based “Does,” with the final level added by Cruess et al. in 2016 [10]—“Is,” where learners consistently demonstrate the attitudes, values, and behaviors expected of them.

At our medical school, the HSS curricular design moves learners up Miller’s pyramid, giving students frequent opportunities to practice and demonstrate HSS competencies in real clinical activities during their clerkship year.

In this study, we examine the impact of embedding tools within the clerkship year to facilitate the practice, demonstration, observation, and assessment of systems-ready physician competencies in the clinical setting. This study was designed to answer the following research questions:

How do faculty and residents rate students’ HSS competencies in the clerkship year?

What are students’ self-assessment of their HSS competency development?

What is the relationship between faculty ratings and student self-assessments of HSS competencies?

What experiences contribute to student development and faculty/resident assessment of HSS competencies?

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants include all undergraduate medical students (N = 50) enrolled in the inaugural class at Dell Medical School. Assessment data were gathered during their second year of medical school when they participated in the following core clerkships: internal medicine, pediatrics, surgery, women’s health, and neurology/psychiatry. Students also completed a 4-week emergency medicine and a longitudinal primary care/family medicine clerkship, but due to the differences in timeframe and assessment methods, data from these clerkships were not included in our analyses.

Curriculum

Dell Medical School was founded on the concept of completely re-thinking undergraduate medical education. The curriculum is named the “Leading EDGE” (year 1—Essentials, year 2—Delivery, year 3—Growth, and year 4—Exploration) [11]. The 4-year curriculum includes health systems science concepts designed to create “systems-ready physicians” within longitudinal courses throughout all years. In year 1, students work through problem-based learning cases and simulated interprofessional activities which embed health systems science concepts. In year 2, students practice and are assessed on the application of these HSS competencies in the setting of the clinical clerkships. In year 3, students apply these skills during a 9-month team project focused on benefitting the local community, and in year 4, students apply these skills to their career specialty within clinical electives.

We linked our HSS curriculum to the Gonzalo et al. curricular framework [2]. See Table 1 for specific examples of how these domains are taught throughout the curriculum and how they are assessed during the core clerkships. The core domains of health care structures and processes, as well as health system improvement, are assessed in all clerkships by observing how students help patients navigate a local or national health care system problem, as well as problem-solving in health care by offering potential solutions. One example of how the domain of population and public health is assessed is by observing students’ cultural competency skills when interacting with patients. In specific clerkships, students reflect on health disparity issues they have noted during their patient interactions. Additionally, students are expected to start to implement basic concepts of value-based care in their write-ups and treatment plans. Related to health information technology, since the introduction of the new Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines on student documentation in February 2018, we implemented policy changes that allow student documentation in the electronic medical record to apply towards billing. We concurrently revised hospital policies allowing order-entry by clerkship students. These steps contributed further important “value-added” components to student education and patient care.

Table 1.

The systems-ready physician: implementation in clerkship year

| Domain | Teaching Examples of where this is taught or reinforced in clerkship-based MS2 year |

Assessment Where/how this is assessed in clerkship-based MS2 year |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical performance assessment form | Required assignments | Optional assignments/projects | ||

| Core domains | ||||

| Health care structures and processes |

Health care structures and processes are taught during all clerkship intersessions in a large group using the AMA Health Systems Science textbook as a reference. These concepts are incorporated in daily rounds and patient write-ups in all clerkships. For example: all clerkships address transitions of care, care coordination and collaboration in the context of clinical care Teams discuss concepts around microsystems and processes occurring in outpatient and inpatient settings and an awareness of fragmentation encountered by patients in healthcare Encourage students to identify health systems problems, and offer solutions that are insightful and innovative Pediatrics embed discussions of Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, disability benefits for children in the context of clinical care Identify importance of teamwork within clinical teams and communities |

L: Problem Solving/Innovation in Health Care (whether students are able to offer solutions to health systems problems that are insightful and/or innovative) | Peds—Students identify health system problem for one patient, then provide innovative solution that can be applied to similar patients | |

| Health care policy, economics, and management | Is taught in the longitudinal leadership course and reinforced in the clerkships | SBP: Health Care System Context (whether students are able to demonstrate knowledge of the health care system locally and nationally and to help the patient and team work through a system problem) | Peds—Students choose to identify a patient impacted by health care policy and describe the downstream effects on health care systems | |

| Clinical informatics and health information technology |

During their clinical skills course (DOCS), students are taught core principles about patient security and rights protection in regard to data; students taught to develop awareness of real time data viewing and decision support Students, through practice, are made aware of current functionality and challenges in current health information exchange |

SBP: Health Care System Context |

Clinical teams provide feedback on student documentation in two areas: Students documentation in the EMR counts towards billing on most clerkships. Students have single order entry privileges in the EMR. |

|

| Population and public health |

All clerkships in varying degrees provide didactics in: Health care disparities, vulnerable patient populations, provider factors, and social determinants of health Skills needed to work with patients from diverse backgrounds |

ICS: Cultural Competency Skills | Peds—Students choose a patient population to discuss how they interact with the health care system, identify available public resources, and propose how providers can promote their health | |

| Value-based care |

Value-based concepts are taught during all clerkship intersessions in a large group setting using on line modules as a reference. Internal Medicine and Pediatrics clerkship students taught SOAP-VS (Subjective-Objective-Assessment-Plan-Value-Safety) verbal presentation format to address potential value and safety discussions include topics around quality of care, cost, patient safety and patient-centered care Value-based Care (VBC) write-ups are required in IM, Pediatrics, Surgery and WH |

SBP: Health care system context; Patient Safety; Interprofessional Care L: Problem Solving/ Innovation in Health Care |

Psych/Neuro—Lead team on VBC (value-based care) oral presentations during rounds Clinical teams provide feedback on VBC discussions in SOAP-VS write-ups in IM and Pediatrics Students expected to address value and safety in their treatment plans Students are assessed in their ability to recognize and identify important safety events Feedback is given on written assignments |

Peds—Quality improvement project addresses patient safety; Surgery—Present case study on VBC and propose innovative solutions; WH—Patient safety reflective write-ups |

| Health system improvement |

WH—Students taught to journal observations and address areas for improvement within a process or system. Pediatrics—Students are engaged in a hospital Quality Improvement project; they are taught change management, quality improvement skills, tools, methods, and principles |

SBP: Health care system context; Patient Safety; Interprofessional Care L: Problem Solving/ Innovation in Health Care |

WH—The clerkship director provides feedback on the journal observations. | Peds—QI project—Students offer solutions and ideas for next PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) cycle |

| Cross-cutting domains | ||||

| Leadership and change agency |

Leadership concepts are taught in the four year Leadership curriculum (leading self and leading within systems) Students taught and encouraged to suggest and implement changes in the health care systems |

L: Initiative; Problem Solving/ Innovation in Health Care |

Feedback is given on required project work: WH—Journaling of observations and recommendations for practice change, participate in departmental patient safety conference; Surgery – portfolio of work and leadership essay; |

Peds—Quality improvement project Students are assessed using the Clinical Performance Assessment form items under Systems-Based Practice and Patient Safety. |

| Teamwork and interprofessional education | In the 4-year Interprofessional Education course, students are taught knowledge and awareness of interprofessional providers’ roles and skills, communication required to function in teams in an integrated system, skills to function effectively in a team and apply reflective practice in the context of quality improvement and patient safety. These skills are applied in all of the clerkships. |

SBP: Interprofessional Care (the expectation that students not only work appropriately with existing health care teams, but also propose innovative solutions involving other health care professionals) |

IM—Care coordination with nursing and primary care providers; WH—Students coordinate multidisciplinary efforts to meet patient needs; All clerkships—multidisciplinary rounds |

Students receive feedback on clerkship specific projects: Peds—Apply reflective practice in context of QI project that addresses patient safety |

| Evidence-based medicine and practice | In several clerkships, students practice using the PICO (patient population, intervention, comparison, outcomes) framework when answering a clinical question using evidence-based medicine (EBM). Students are encouraged apply the evidence to their patients’ care but to also articulate the limitations of the evidence. | MK: Evidence-Based Medicine |

Students receive feedback on written assignments: IM and Pediatrics: Evidence-based medicine write-up (PICO) All clerkships assess application of EBM when suggesting treatment plans and justifying next steps |

Psych/Neuro—Lead team on EBM oral presentations during rounds and are given feedback |

| Professionalism and ethics | Professionalism concepts are taught and practiced in the first year within the clinical skills course, the interprofessional education course and the problem based learning sessions. These behaviors and skills are practiced in all clerkships. |

ICS.: Interpersonal Skills; Cultural Competency Skills PBL: Emotional Intelligence/ Situational Awareness; Continuous Personal Improvement P: Integrity and Work Ethic |

During rounds, faculty and residents observe student behavior in terms of interactions with patients as well as other healthcare providers and team. | |

| Scholarship | Pediatrics—Students coached how to present scholarly project regarding patient safety to hospital leadership; students apply knowledge and skills needed for quality improvement as well as presenting change management as leaders |

L: Initiative; Problem Solving/ Innovation in Health Care PBL: Clinical Curiosity; Continuous Personal Improvement. |

Peds, Surgery—Students receive feedback on optional quality improvement work | |

| Linking domain | ||||

| Systems thinking | Concepts are taught and practiced in the first year within the clinical skills course and the interprofessional education course. These behaviors and skills are practiced in all clerkships. |

L: Problem Solving/ Innovation in Health care SBP: Health Care System Context |

Peds, Surgery, WH—optional project work on health care systems and social determinants of health | |

PICO patient population, intervention, control, outcomes; VBC value-based care; EMR electronic medical record; Peds pediatrics; WH women’s health; Psych/Neuro psychiatry and neurology; IM Internal Medicine

Competencies on Clinical Performance Assessment Form: P professionalism; MK medical knowledge; PBL practice-based learning; L leadership; SBP systems-based practice; ICS interpersonal and communication skills; QI Quality Improvement

The cross-cutting domains (leadership/change agency; teamwork and interprofessional education; evidence-based medicine/practice; professionalism and ethics) are assessed in all clerkships. For instance, students write value-based care and patient safety write-ups and are encouraged to embed value and safety considerations in their verbal presentations, thereby helping reinforce these important aspects of care and leading by influencing team culture. Additional cross-cutting domains, such as teamwork and interprofessional care, are likewise highlighted, including opportunities to contribute to care coordination with other health care professionals, as well as active participation in multidisciplinary rounds. Moreover, students are assessed on emotional intelligence and situational awareness, which they learn about in their longitudinal leadership course.

Some HSS aspects that are difficult to observe in the clinical setting are assessed using other methods, such as scholarly work opportunities, in the form of honors projects offered in some clerkships. These projects help assess leadership, initiative, clinical curiosity, continuous personal improvement, and teamwork. Examples of individual projects include developing a professional portfolio, writing a reflection to discuss personal implicit bias or cultural competency, and developing a learning plan with goals and measurements of achievement. Examples of team honors projects include designing innovative educational products and participating in student-led quality improvement (QI) projects utilizing plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles. For instance, one QI project gained the attention of hospital administrative leadership who then considered its widespread implementation. Although clinical faculty may have more difficulty in observing leadership behaviors in the day-to-day clinical setting, students can demonstrate this using other methods, such as the projects described.

The linking domain of systems thinking is assessed by observing students’ knowledge of health care system resources and the use of these resources. Examples include teaching and assessing students on effective patient “handoffs,” as well as assessing students’ awareness of health care systems resources, and the application of this knowledge to their patients’ care.

Faculty development tools to support both the teaching and assessment of HSS competencies were created by the medical education leadership team, shared, and discussed with the clerkship directors, who subsequently tailored these tools to the individual needs of their departments. Faculty and resident development occurred in several settings, including faculty meetings and resident house-staff meetings, as well as educational workshops for both residents and faculty. Specific education occurred around the use of the student assessment tools and forms.

Assessments

Assessment helps drive learning. To help students move from “knows” or “knows how” to “does,” and finally to “is,” assessment is integrated early into their practice as systems-ready physicians and continues at multiple steps along their learning journey. Importantly, grading in all courses and clerkships at Dell Medical School is based on a criterion-based model, rather than normative model, further highlighting the expectation of a team-based and collaborative work environment and a focus on competency development.

Students are assessed by clinical faculty/residents in each of their clerkships and self-assess their competencies prior to and after their clerkship year. Both assessment forms address the HSS competencies and are linked to Dell Medical School’s seven core competency domains: (1) leadership and innovation, (2) patient care, (3) medical knowledge, (4) interprofessional communication, (5) practice-based learning and improvement, (6) systems-based practice, and (7) professionalism.

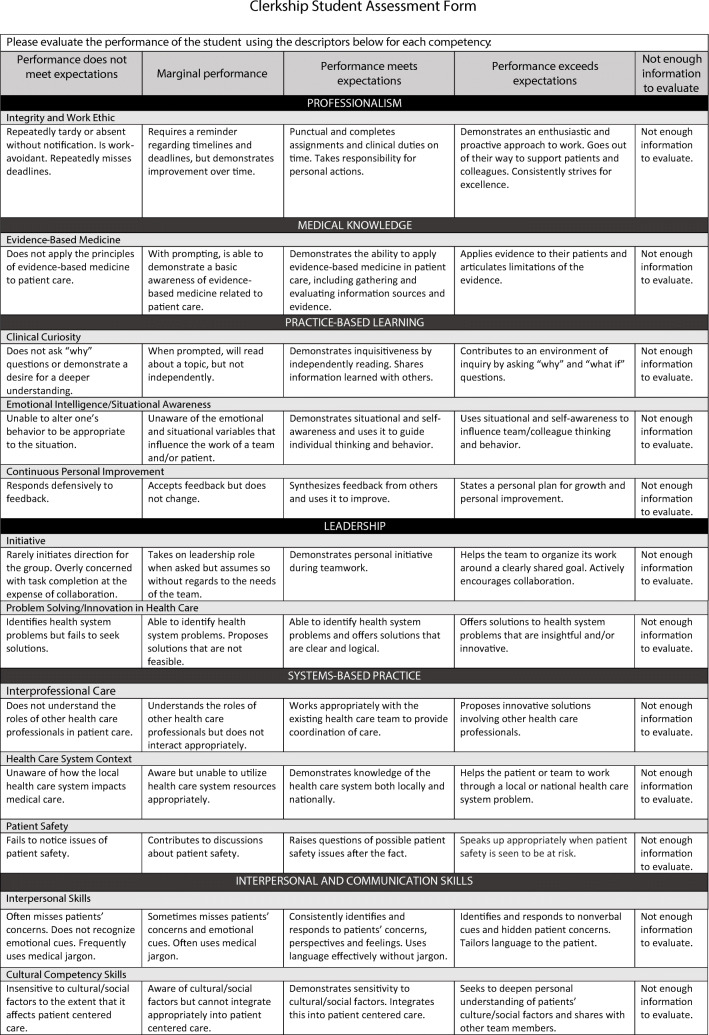

The clinical performance assessment form which faculty and residents complete was created by a working group of clerkship directors and an assessment expert. The group reviewed multiple assessment forms from other medical schools and guidelines from published literature on workplace-based assessments to inform the creation of the form. The final version was approved by the curriculum committee. The form consists of 17 items. Sub-competencies assessed on this form highlight skills and behaviors necessary to become a “systems-ready physician,” including items such as innovation in health care, interprofessional care, emotional intelligence, and value-based care, as well as patient safety considerations. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (exceeds expectations, meets expectations, marginal, and does not meet expectations) with an option to select “NA - not enough information to evaluate”, and written criteria anchors at each level. See Figure 1 for sample items. To examine the reliability of the form, a generalizability study was conducted for each of the 5 core clerkships. Due to the large amount of missing data, only assessment forms that contained ratings for over 60% of items on the form were included in the analyses. Results revealed reliability coefficients ranging from .32 to .75. These results guide further faculty development efforts to better train faculty how to use the form.

Fig. 1.

Clerkship student assessment form

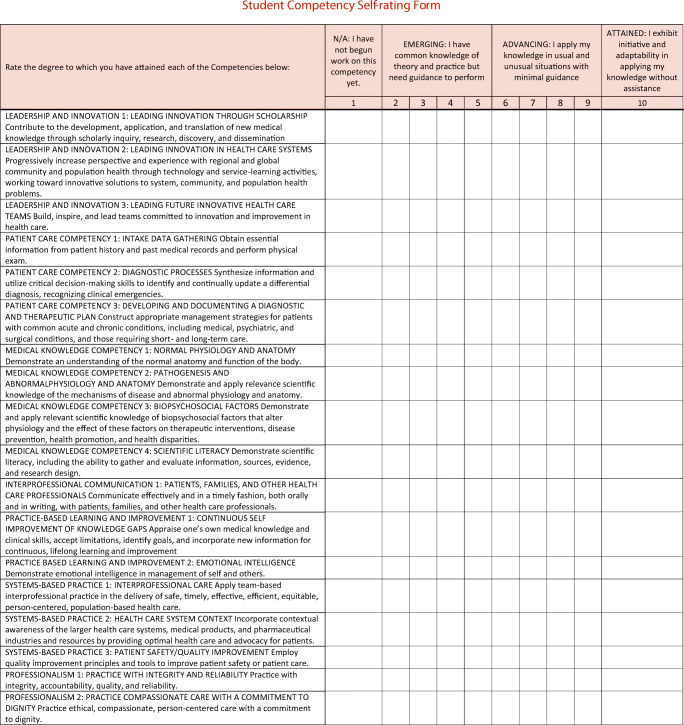

The student self-assessment form consists of 18 items. For each self-assessment item, students rate themselves on a scale from 1 (have not begun work on this competency) to 10 (attained-exhibit initiative and adaptability in applying knowledge without assistance). See Figure 2 for sample items. An open-ended question asking students to describe the most significant experience that contributed to their development of the competency followed each item. Purposefully providing students with this assessment data and encouraging self-reflection on progress further highlights how pivotal these skills are for effective patient-care and clinical practice.

Fig. 2.

Student competency self-rating form

Results

Faculty/Resident Assessment of Students

To answer the first research question, how do faculty and residents rate students’ HSS competencies in the clerkship year, we examined clinical performance assessment ratings. Assessment forms were released at the end of each 2-week period of an 8-week rotation to faculty and/or residents who worked with a student during those two weeks. The number of faculty raters varied across clerkships depending on the teams or services to which students were assigned. During the academic year, 2328 clinical performance rating forms were completed by faculty and/or residents.

A rating of “does not meet expectations” occurred on less than 1% of the completed forms. These occurred on contributing forms completed at the end of each 2-week period. Formative feedback was provided to the students, and there were no “does not meet expectations” in HSS competencies on final grade forms. In the few instances that this was documented, there was no consistency in the behavior over time or clerkships, so no remediation was required. More commonly, residents and faculty marked the HSS item as “unable to assess” suggesting they did not prompt or observe these behaviors. In fact, we discovered that certain competencies are more difficult to observe than others in the clinical setting. NA was selected on over 30% of the rating forms submitted by faculty/residents for the items related to patient safety, problem-solving/innovation in healthcare, and health care system context—competencies integral to a “systems-ready physician.” Ongoing faculty and resident training is underway to improve these assessments.

Once NA responses were removed, averages were calculated for each item and competency domain. Faculty/residents rated students highest in professionalism and lowest in systems-based practice, particularly interprofessional care and health system context. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Student and faculty ratings in clerkship year

| Student self-ratings N = 50 students |

Faculty/resident ratings of students N = 2328 assessments completed |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency domain | Items 10-point scale: 1 (have not begun work on this competency) to 10 (attained-exhibit initiative and adaptability in applying knowledge without assistance) |

Beginning of year Mean |

End of year Mean |

Items 4-point scale: 1 (does not meet expectations) to 4 (exceeds expectations) |

Mean (SD) | % NA—not enough information to evaluate |

| Leadership and innovation |

-Scholarship -Innovation in health care -Leading future teams |

4.37 | 5.73* | Initiative | 3.23 (.52) | 21.6% |

| Problem-solving/innovation in health care | 3.18 (.43) | 37.6% | ||||

| Patient care |

-Intake data gathering -Diagnostic processes -Developing a plan |

5.03 | 7.80* | Patient history | 3.29 (.50) | 11.6% |

| Physical/mental status | 3.18 (.46) | 18.9% | ||||

| DDx and diagnostic reasoning | 3.21 (.52) | 15.2% | ||||

| Treatment plan | 3.14 (.48) | 16.7% | ||||

| Medical knowledge |

-Normal physiology and anatomy -Pathogenesis and abnormal physiology and anatomy -Biopsychosocial factors -Scientific literacy |

5.83 | 7.38* | Evidence-based medicine | 3.15 (.52) | 13.9% |

| Interprofessional communication | -Communication with patients, families, and health care professionals | 5.70 | 7.80* | Interpersonal skills | 3.37 (.53) | 15.4% |

| Oral presentation skills | 3.24 (.53) | 11.9% | ||||

| Cultural competency skills | 3.31 (.49) | 22.7% | ||||

| Practice-based learning and improvement |

-Continuous self-improvement of knowledge gaps -Emotional intelligence |

6.35 | 7.80* | Clinical curiosity | 3.38 (.59) | 13.2% |

| Emotional intelligence/situational awareness | 3.28 (.56) | 13.8% | ||||

| Continuous personal improvement | 3.27 (.52) | 19.3% | ||||

| Systems-based practice |

-Interprofessional care -Health care system context -Patient safety/quality improvement |

4.03 | 6.57* | Interprofessional care | 3.15 (.41) | 20.2% |

| Health care system context | 3.15 (.41) | 34.3% | ||||

| Patient safety | 3.30 (.53) | 38.8% | ||||

| Professionalism |

-Integrity and reliability -Compassionate care with a commitment to dignity |

6.95 | 8.70* | Integrity and work ethic | 3.43 (.56) | 10.3% |

*Significant increase in student self-rating from beginning to end of year, p < .01

Student Self-Assessment

To answer the second research question, student self-assessment form competency domain averages were calculated at the beginning and end of the year. Paired t test analyses revealed significant increases in students’ self-ratings from the beginning of the year to the end of the year in all domains. Students rated themselves highest in professionalism at both time points and lowest in systems-based practice at the beginning of the year and leadership and innovation at the end of the year (see Table 2).

To examine the third research question, to what extent are faculty/resident and student self-assessments related, we conducted correlation analyses. There is a statistically significant correlation between students’ self-rating and faculty ratings in the professionalism domain (r = .307, p < .01), but not in any of the other competency domains. This aligns as both faculty and students rated professionalism competency highest.

Curricular Experiences

To answer the fourth research question in determining which experiences contributed most to student competency development, we examined responses to open-ended items on the student self-assessment form. Students consistently mentioned QI projects; value-based care write-ups; patient population, intervention, control, outcome (PICO) assignments; evidence-based medicine (EBM) write-ups; and discussions of value-based care during rounds and patient presentations as experiences in the clerkships that contributed to their development of leadership and systems-based practice competencies. One student commented, “I was able to use a lot of QI concepts I learned in the progression of my pediatrics QI project.” Another stated, “we were asked to integrate value discussions in our daily presentations, and many faculty/residents commented that these concepts were introduced to them very late in their training; although it may not be fully appropriate to discuss value in all patient cases, having that as part of our thought process in presenting plan of care was invaluable.” These experiences prompted students to think like a “systems-ready physician” evident by another student’s comment, “Discussing costs of patient care and how patient social factors impact health during the clerkships helped me see that there is so much more to health care than just medicine.”

Discussions during clerkship grading committee meetings revealed that additional data beyond faculty assessment forms are needed to inform students’ summative clinical assessment form and final grade. Since not all competencies may be observable on a daily basis by faculty and residents as seen by the large amount of NAs on the faculty forms, the projects completed by students provide additional data to the grading committee about a student’s knowledge and skills. For example, in the Department of Pediatrics, several competencies are highlighted by graded narrative reflections as well as participation in hospital quality improvement projects. These projects are graded using scoring rubrics to ensure quality and standards are met. The same assignments and activities mentioned by the students as opportunities to develop competencies are also used as assessment data for faculty.

Discussion

Our results highlighted several interesting points for discussion. Not surprisingly, we realized that some HSS competencies are difficult to observe and assess in the clinical setting, with a higher percentage of “NA” (“not enough to evaluate”) on the assessment form related to problem-solving/innovation in health care, health care system context, and patient safety items. Clerkship directors and medical education leaders have reviewed the assessment forms for item clarity and made changes where needed. Areas that had a higher percentage of “NA” are particularly highlighted during faculty and resident development sessions with discussions of what to look for and how to prompt students to make these behaviors observable. Additional assignments have been created and embedded in the clerkships as a venue for students to demonstrate their competence in what may be otherwise difficult to demonstrate areas. The success of our faculty and resident development efforts is illustrated by the decreased frequency of using the NA response over time.

When examining both faculty ratings and students’ self-assessments, we feel students are progressing at the level expected by the curriculum developers. The expectation for students is that by the end of their second year, they should be emerging in their leadership and innovation and systems-based practice competencies, but further along in professionalism, interprofessional communication, and practice-based learning and improvement. This aligns with assessment results.

We believe that there are multiple factors that contribute to students’ higher ratings in these areas. These include our a holistic medical school admissions process, which uses team-based interviews and multiple mini-interviews to assess non-cognitive skills [12]. Additionally, during the first year of medical school (Essentials), problem-based learning, as well as the interprofessional education and clinical skills courses, entail working together with other students on a team with input and feedback from faculty members and peers regarding their professionalism and communication. The frequent feedback prompts students to make iterative adjustments as needed to improve their performance throughout their first year.

While there was a significant correlation between students’ self-rating and faculty/resident assessments in the area of professionalism, we did not see correlations in any of the other competency domains. This aligns with research suggesting that people may not be accurate self-assessors [13]. The annual self-assessment was designed to be a prompt for reflection and to help students focus on their development over time and areas they can continue to work one. By continuing to use these reflection opportunities, we hope to develop students’ habits of self-regulated learning [14].

Conclusions

Embedding HSS concepts in undergraduate medical education and assessing these competencies in the clerkships are leading to culture change. Student perception of growth in these competencies is seen across the clerkship year including the important competencies of patient safety and quality improvement. In addition to introducing a widespread culture change, students—who are our future physicians—learn to embed these concepts in their daily practice from early on. Additionally, there is a value-added component of students contributing to patient care and team effort by participating in roles such as QI team extenders, serving as care transition facilitators, and undertaking health system research projects, amongst other roles.

Ultimately, we are assessing if HSS competencies are integrated into the students’ clinical practice long term. We are learning that, as we try to embed these “systems-ready physician” concepts into our clinical curriculum, faculty and residents are finding the assessment of some of these competencies challenging. Partnership with faculty and residents at the graduate medical education level, including ongoing faculty and resident development [15], is crucial to close this gap.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Sue Cox, executive vice dean of academics and chair of the Department of Medical Education, and Dr. Christopher Moriates, assistant dean for health care value in the Department of Medical Education, for their important contributions in designing the Dell Medical School Leadership and Health Systems Sciences Curricula.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Medical Association. Accelerating change in medical education. https://www.ama-assn.org/amaone/accelerating-change-medical-education. Accessed April 27, 2019.

- 2.Gonzalo, Jed D et al. Health systems science curricula in undergraduate medical education: identifying and defining a potential curricular framework Academic Medicine, 04/2016, Volume 92, Issue 1 Miller GE. The Assessment of Clinical Skills/Competence/Performance. Acad Med 1990. 65(9): 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Gonzalo JD, Haidet P; Blatt B, Wolpaw DR Exploring challenges in implementing a health systems science curriculum: a qualitative analysis of student perceptions Medical Education, 05/2016, Volume 50, Issue 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gonzalo JD, Caverzagie KJ, Hawkins RE, Lawson L, Wolpaw DR, Chang A Concerns and responses for integrating health systems science into medical education Academic Medicine, 06/2018, Volume 93, Issue 6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gonzalo JD; Lucey C, Wolpaw T, Chang A Value-added clinical systems learning roles for medical students that transform education and health: a guide for building partnerships between medical schools and health systems. Academic Medicine, 08/2016, Volume 92, Issue 5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gonzalo JD, Dekhtyar M, Hawkins RE, Wolpaw DR. How can medical students add value? Identifying roles, barriers, and strategies to advance the value of undergraduate medical education to patient care and the health system. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1294–1301(8). doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalo JD, Graaf D, Johannes B, Blatt B, Wolpaw DR. Adding value to the health care system: identifying value-added systems roles for medical students. A J Med Qual. 2017;32(3). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gonzalo JD, Thompson BM, Haidet P, Mann K, Wolpaw DR A constructive reframing of student roles and systems learning in medical education using a communities of practice lens Academic Medicine, 12/2017, Volume 92, Issue 12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63–S67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91(2):180–185. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School Leading Edge Curriculum https://dellmed.utexas.edu/education/academics/undergraduate-medical-education/leading-edge-curriculum. Accessed April 28, 2019.

- 12.Reiter HI, Eva KW, Rosenfeld J, Norman GR. Multiple mini-interviews predict clerkship and licensing examination performance. Med Educ. 2007;41(4):378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2007.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White CB, Gruppen LD, Fantone JC. Self-regulated learning in medical education. Understanding medical education. 2014. pp. 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalo JD, Ahluwalia A, Hamilton M, Wolf H, Wolpaw DR, Thompson BM Aligning education with health care transformation: identifying a shared mental model of "new" faculty competencies for academic faculty Academic Medicine, 02/2018, Volume 93, Issue 2. [DOI] [PubMed]