Abstract

Purpose

Current trends in medical school education indicate an existing need for increasing medical student exposure to pharmacotherapy education. The objectives of this study are to describe the development of an interprofessional, application-based Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care selective for 3rd year medical students and to assess its influence on knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to pharmacotherapy of high-risk medications and patient populations.

Methods

The selective was implemented across fourteen cohorts of medical students that were evaluated over a 5-year academic period (n = 68). Our curriculum was unique in that it merged basic pharmacology and pharmacotherapy concepts with application-based medication management of high-risk patients in addition to the incorporation of an interprofessional home visit experience.

Results

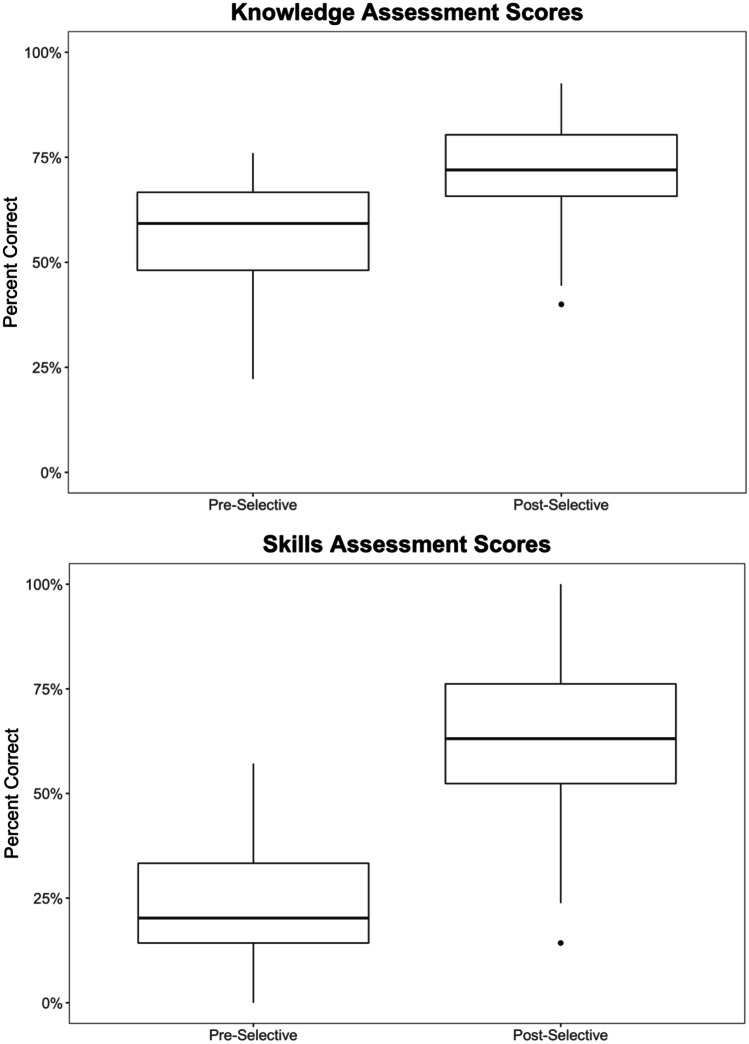

Pre- and post-assessment analyses found statistically significant improvements in students’ pharmacotherapeutic knowledge and skills. There was a significant increase in the knowledge post-test mean score (71.8; SD = 11.2) compared to the pre-test mean score (57.3; SD = 11.9; P < .001). A similar trend was observed for the skills mean score in which the post-test average (63; SD = 16.9) was significantly higher than the pretest average (23.3; SD = 14.4; P < 0.001). Students’ attitudes also improved when rating their confidence in completing specific tasks such as recommending dosing regimens and utilizing drug information resources.

Conclusion

This intervention provided 3rd-year medical students with opportunities to improve their knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to the pharmacotherapeutic management of high-risk medications and patient populations while exploring meaningful interprofessional interactions with faculty and learners from other disciplines.

Keywords: Interdisciplinary medical education, Problem-based learning, Qualities, Skills, Values, Attitudes, High-risk medications, Pharmacotherapy curriculum, Primary care education

Introduction

Most medical school curricula incorporate pharmacotherapy content during the preclinical years interspersed alongside the other basic sciences. Upon the completion of preclinical education modules, there may be limited structured opportunities focusing on pharmacotherapy and prescribing habits throughout the remainder of 4-year medical school programs [1]. A review of the literature indicates that most of the formal application-based pharmacotherapy education occurs at the medical resident level [2, 3]. To encourage pharmacotherapy education in medicine, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Group on Pharmacotherapy promotes the incorporation of evidence-based pharmacotherapy education in the family medicine setting. Family medicine educators are encouraged to identify methods to improve competency-based medical training in pharmacotherapeutics and to develop interdisciplinary pharmacotherapy learning experiences in family medicine training programs [4]. Strategies that incorporate these objectives in medical school curricula are still lacking. The limited exposure of pharmacotherapy education among recent medical graduates makes them susceptible to prescription errors leading to adverse drug events (ADEs) [5].

In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported that errors in prescribing and monitoring of medications were among the top five risk factors associated with medication mishaps [6]. Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 1.3 million emergency department visits and 350,000 hospitalizations occur from ADEs each year in the USA, resulting in estimated 3.5 billion dollars in annual healthcare costs [7, 8]. Ghosh and Ghosh found that medical providers generally display low levels of confidence in prescribing once completing their formal medical school education [9].

Although any medication can lead to a potential adverse drug event, certain classes of medications have higher risks. Budnitz et al. and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identified blood thinners (i.e., warfarin and oral antiplatelets), antidiabetic agents (i.e., insulins and oral hypoglycemics), and opioid medications as medications most frequently associated with ADEs [7, 10]. Additionally, the CDC reports that cardiovascular agents (i.e., digoxin) are implicated for higher risk of ADEs [7]. Antibiotic medications (i.e., sulfonamides, penicillins and quinolones) have also been identified as a top leading cause of ADEs [11]. The CDC concludes that most of these ADEs are preventable with close monitoring from healthcare providers [7].

There are rising efforts by several national organizations in evaluating the need for plausible interventions and strategies to improve the medication-use process and reduce medication errors. Healthy People 2020 initiatives recommend reducing adverse drug events by enhancing medical error monitoring. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report entitled, “Preventing Medication Errors,” identifies lack of competencies in safe medication management practices and low training levels in clinical pharmacology as contributing factors for prescription malpractices in healthcare settings [12]. The IOM recommends increased clinical pharmacology curriculum content during medical school education as a solution [12]. These collaborative efforts underscore the need for heightened interdisciplinary focus in identifying strategies that will decrease prescribing errors made by healthcare providers.

There is some literature available that describes educational interventions that focus on improving prescribing ability and confidence [4, 13]. However, there is a dearth of information that specifically evaluates pharmacotherapy educational programs for medical students. The objective of our study is to describe the development of an interprofessional, application-based “Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care” selective experience for 3rd-year medical students and to assess its influence on the knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to pharmacotherapy of potentially high-risk medications and patient populations in the medical students that were enrolled. The curriculum discussed in this paper provides an innovative approach to providing pharmacotherapy education to third-year medical students.

Methods

Setting and Participants

We conducted this study at the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Texas Tech Health Science Center of El Paso, Paul L. Foster School of Medicine (PLFSOM) in El Paso, Texas. The city of El Paso is located on the US-Mexico border and has a population of over 800,000 people, of whom approximately 83% are of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, and 21% live below the poverty line [14]. El Paso’s large binational and multicultural community creates a unique environment where people engage in simultaneous use of both United States and Mexican healthcare systems for healthcare needs. This creates an additional demand for increased pharmacotherapy knowledge in healthcare prescribers in order to avoid ADEs. Students enrolled into the Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective were 3rd-year medical students at PLFSOM. Our team of faculty involved in developing and teaching this selective learning experience included pharmacy faculty from the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP)/University of Texas (UT) at Austin Cooperative Pharmacy Program in El Paso, TX, and medical faculty from the Department of Family Medicine. Pharmacy students from the Cooperative Pharmacy Program also participated in the selective along with Master of Social Work Students from UTEP. This project was deemed exempt by TTUHSC IRB as part of evaluation of the family medicine clerkships.

Pharmacotherapy Selective

Our curriculum for 3rd-year medical students at PLFSOM consisted of three 16-week blocks that provide students with integrated teaching and learning experiences. These blocks include family medicine/surgery, obstetrics/gynecology/pediatrics, and internal medicine/psychiatry. Within the family medicine block, students could choose from one of several longitudinal selective experiences including chronic disease management, prenatal care, pharmacotherapeutics in primary care, sports medicine, geriatrics, integrative medicine, Native American medicine, HIV, patient education, and service learning. In general, four to eight students per block were assigned to the Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective and the course met one-half day per week during the 16-week longitudinal block.

Our team of pharmacy and family medicine faculty jointly developed the Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective using evidence to direct the selection of topics for inclusion [10]. We designed this selective to employ a variety of learning strategies including a combination of online content (including recorded lectures and/or assigned readings) and live content (workshop, discussions, presentations). The topics we selected for incorporation into this selective also focused on at-risk populations for adverse drug events (i.e., geriatric patients, transitional care patients). Furthermore, this selective focused on medications that are most likely to cause adverse drug events (i.e., anticoagulants, hypoglycemic agents, opioids). Table 1 summarizes the various modules, topics, and activities that were included.

Table 1.

Overview of pharmacotherapeutics in primary care selective

| Introduction |

• Review of syllabus • Basic principles of pharmacology, pharmacokinetics |

| General pharmacy topics |

• Medication information resources workshop • Strategies for dose adjustment of medications in patients with renal impairment |

| Anticoagulants |

• Pharmacotherapy of anticoagulants • Prophylaxis, treatment of VTE • Peri-operative issues with anticoagulation |

| Hypoglycemics |

• Oral agents for the treatment of type 2 diabetes • Insulin management workshop |

| Pain management |

• Approach to pain management • Pharmacotherapy of opioids (including opioid rotation and conversion) |

| Other topics |

• Herbal product safety • Pharmacotherapy of hypertension • Pharmacotherapy of infectious diseases • Pharmacotherapy considerations in the elderly (Beers Criteria, START, STOPP) |

| Home visit experience |

• Interprofessional (medical students, pharmacy students, social work students) • Pre-discharge visit (complete chart review, coordinate timing of discharge visit) • Team home visit (targeted physical assessment, medication reconciliation, assessment of home environment/patient needs) • Debrief/presentation (patient synopsis, drug-related problems and action plan, patient education materials, comments about team functioning) |

START Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment, STOPP Screening Tool of Older People’s potentially inappropriate Prescriptions, VTE Venous Thromboembolic Event

By completing this selective, the medical students were expected to (1) demonstrate the use of evidence-based drug information resources, (2) design safe and appropriate treatment plans using evidence-based guidelines for patients at high risk for adverse drug events (i.e., geriatric populations, patients on anticoagulants, hypoglycemic agents, and opioids), (3) identify drug-related problems and develop action plans to safely transition patients from in-patient to out-patient settings, and (4) compare and contrast the dynamic roles within an interdisciplinary healthcare team.

We conducted each session over the course of a 4-hour block since medical students were assigned to the selective one-half day per week. Each session was led by either a pharmacist or a physician faculty member; a few sessions were co-led by both pharmacy and medicine faculty. We provided a short didactic-style lecture during the first part of each session to ensure that students had the appropriate foundational knowledge related to the topic. The rest of the session was devoted to interactive, case-based application of pharmacotherapeutic content that utilized problem-based learning strategies. We first provided students with the opportunity to work through cases independently; they were then paired up or placed in a small group for discussion with peer(s). Finally, the course faculty would lead the students in a large group discussion of the cases. In addition to providing an opportunity for students to ask questions and clarify concepts, these discussions allowed students to share and reflect on their learning. When schedules allowed, one or two 4th-year Doctor of Pharmacy students would join the sessions with the medical students to provide an opportunity for interprofessional education. We then paired up medical and pharmacy students to discuss cases in small groups before large group sharing occurred.

An interprofessional home visit experience was also incorporated into the 16-week selective block to allow students to explore transitions-of-care issues for a family medicine patient being discharged home from the hospital. We intentionally scheduled these visits to allow for both medical and pharmacy students to attend these visits under the supervision of either a medical or pharmacy faculty member. When possible, scheduling also allowed for the participation of a social worker student. The activities conducted during the home visit experience are summarized in Table 1.

Assessment Instrument

To evaluate the Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective, our team developed an assessment tool to assess knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Items that were included in the assessment were selected by our pharmacy and medicine faculty based on module learning objectives. The knowledge section of the assessment included 17 multiple choice questions about general pharmacology and pharmacotherapy knowledge of diabetes, hypertension, anticoagulation, antimicrobials, pain management, and geriatric patient considerations. A 4-point Likert-type scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree) was used to analyze the attitudes section of the assessment (13 items). Attitudes were measured by asking students to rate their confidence in performing various tasks related to pharmacotherapy management (e.g., adjust a patient’s dose based on renal function estimates, convert between opioid regimens) as well as their perceived confidence in interdisciplinary collaborations (refer to Table 2). The skills section of the assessment utilized four case scenarios. In these cases, students were asked to perform dose calculations and recommend monitoring strategies. Table 3 includes a summary of the cases in the skills section of the assessment. We administered this assessment instrument to each student at the start of the selective during the first orientation session. To reduce post-assessment carryover effects, students were not provided with a copy of the instrument nor were they provided a review of correct responses for knowledge and skills-based items after the pre-assessment. The same version of the assessment was also administered at the end of the selective during the final session at the end of the 16-week block. The items in this survey remained constant throughout the study period; there was no need to modify questions during this period. Of note, we did not use the results of these assessments for grading purposes for students completing this selective; rather, they were used to evaluate the quality and impact of the selective experience. Also, this assessment was developed for the selective and it has not been used previously or reported in the literature.

Table 2.

Items included in the attitudes section of the instrument

| Question number | I am confident in my ability to: |

|---|---|

| Q1 | Locate and utilize appropriate medication and disease-state information resources |

| Q2 | Adjust a patient’s medication dose based on renal function |

| Q3 | Select an appropriate anticoagulant regimen and monitoring plan for initial treatment of VTE |

| Q4 | Adjust a patient’s warfarin regimen based on their INR and other relevant patient-specific factors |

| Q5 | Devise an appropriate insulin regimen for a diabetic patient |

| Q6 | Convert between opioid medications |

| Q7 | Recommend a maintenance and breakthrough treatment plan for chronic pain patients |

| Q8 | Take a complete medication history (including prescription, OTC medications, herbs, supplements) |

| Q9 | Evaluate a medication regimen for an older adult patient and identify potentially inappropriate medications |

| Q10 | Apply appropriate treatment strategies in transitioning patients from inpatient to outpatient care settings |

| Q11 | Work with and learn from other healthcare professionals while providing care to patients |

| Q12 | Adapt my role as needed within a healthcare team |

| Q13 | Select culturally and linguistically appropriate treatment and education for patients |

OTC over the counter, INR international normalized ratio, VTE venous thromboembolic event

Table 3.

Summary of case scenarios in skills assessment

| Case | Skills assessed |

|---|---|

| Woman with diabetes who is diagnosed with pyelonephritis to be treated with antibiotic |

• Calculate estimates of patient’s renal function • Utilize drug information resources to identify renal dosing strategies • Recommend appropriate dose for patient |

| Man with history of DVT who is taking warfarin and presents w/ supratherapeutic INR |

• Identify need for use of vitamin K or other reversal strategies • Calculate new dosing regimen for warfarin using nomograms |

| Man with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus who is to be started on insulin therapy |

• Recommend an insulin regimen utilizing basal/bolus insulin strategy • Identify appropriate monitoring regimen |

| Woman with chronic pain taking opioids |

• Identify maximum dose limitations for opioid products containing acetaminophen • Convert patient to a different opioid regimen using long-acting opioid with short-acting agent for breakthrough pain |

DVT deep vein thrombosis, INR international normalized ratio

Data Analysis

Pharmacy faculty members graded pre- and post-assessments utilizing a standardized key. Student scores for the knowledge and skills portions of the assessment were totaled and calculated as percent of items that were “correct.” The students’ knowledge and skills scores were then tested for normal distribution using Q-Q plots and the Shapiro-Wilk’s test. Two-sample paired Student’s t-test with unequal variances was used to compare the pre- and post-assessment scores for the knowledge and skills portions. The alpha level was set at 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval. R software, version 3.6.0, was used. The attitudes portion of the assessment was reported as simple frequencies.

Results

Fourteen cohorts of medical students that participated in this Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective were evaluated over the course of a 5-year academic period. We collected pre- and post-assessment data for a total of 68 students. Only data for students who completed both the pre- and post-assessment were included in the data analysis. Regarding knowledge, there was a significant increase in the post-test mean score (71.8; standard deviation [SD] = 11.2) compared to the pre-test mean score (57.3; SD = 11.9; t = 11.5, 95% CI 12.2–17.4, P < 0.001). A similar trend was observed for the skills mean score in which the post-test average score (63; SD = 16.9) was significantly higher than the pretest average score (23.3; SD = 14.4; t = 18.5, 95% CI 36.5–45.4, P < 0.001). The change in assessment scores is demonstrated using the box plots in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of pre- and post-assessments of knowledge and skills

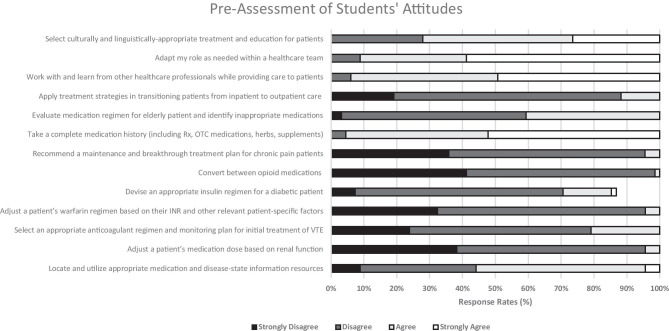

The results from the students’ answers on the Attitudes portion are summarized in Figs. 2 and 3 (Note: response rates on these questions do not always add up to 100% because there were a few answers left blank by a few students on either the pre-assessment or the post-assessment). When analyzing the results of the attitudes assessment, we noted that there was an improvement in the students’ attitudes when rating their confidence in their ability to complete specific tasks (see questions in Table 2). Generally, the students answered more pre-assessment questions with “disagree” and “strongly disagree” specifically in areas relating to dose adjustments for renal function, selecting anticoagulation regimens, adjustments of warfarin medications, and converting between opioid medications in addition to recommended breakthrough treatments for chronic pain patients. This indicated that there was a low level of confidence in their ability to complete specific tasks related to pharmacotherapy (refer to Fig. 2). On the post-assessment, many of the students answered the questions with “agree” and “strongly agree” in the aforementioned areas indicating a high level of confidence in their ability to complete specific tasks (refer to Fig. 3). Of note, the results from the pre- and post-assessments also highlighted that students were more confident in their abilities to adapt their role as part of the healthcare team, collaborate with other health professionals, and select culturally appropriate education upon completing the selective.

Fig. 2.

Pre-assessment of students’ attitudes

Fig. 3.

Post-assessment of students’ attitudes

Discussion

Our Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective was implemented over a 16-week longitudinal block for 3rd-year medical students during their family medicine clerkship. The students that completed the curriculum showed significant improvements in pharmacotherapy knowledge and skills. Students also reported improvements in their attitudes towards managing high-risk medications as well as their ability to work collaboratively with other healthcare professionals while providing care to patients. The problem-based learning strategies implemented in this course were successful in allowing students to apply their knowledge and skills while solving clinically relevant problems. The group sessions also provided students the opportunity to actively engage in meaningful conversations. These discussions were particularly enriching when interprofessional collaboration between medical students and pharmacy students was able to occur. Discussing the various individual approaches allowed students to compare and contrast solutions for patient care based on different perspectives.

While most medical students receive pharmacology as part of their curriculum interspersed with their basic sciences coursework, there is some growing concern that this does not adequately prepare them for the complexities involved in medication management and safe prescribing habits after medical school [15]. It has been reported that typical pharmacology courses in medical school curricula are organized by organ system and focus predominantly on concepts of receptor theory, principles of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and pharmacology of the autonomic nervous systems [16]. These courses have been traditionally structured as lectures usually occurring during the second year of graduate studies and they may provide limited opportunities for small group discussion or other approaches for learning. At our medical school, pharmacology content is covered during the pre-clerkship phase as part of the basic sciences that are organized around clinical schemes in a 2-year course series entitled “Scientific Principles of Medicine” which is delivered during the first two years of the curriculum. While students review the anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of clinical presentations, they also review the pharmacology of medications used to treat the clinical presentations. Our Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective was unique since it allowed students to integrate basic pharmacology with pharmacotherapy concepts during the 3rd year of the curriculum in sessions discussing case-based management of patients taking high-risk medications or patient populations considered to be at high-risk for medication adverse events. These skills were also applied under supervised encounters with patients chosen for the post-discharge home visit exercise. Furthermore, studies have shown that errors in prescribing in the hospital setting are often due to limited pharmacotherapy/pharmacology knowledge from incoming prescribers [12, 17]. To prevent these errors, it has been suggested that medical students be educated on finding adequate dosing information for frequently used medications, adjustment of drug-based factors that may alter doses (i.e., renal impairment), and how to properly review a medical chart to identify important information that may impact pharmaceutical care [17, 18]. Our Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective incorporated activities like these as educational strategies that could potentially decrease the probability of prescribing errors for these students as they transition into clinical practice.

With increasing complexities of healthcare teams, it is important for health professionals to learn how to collaborate and work together early on in their educational training [19]. Studies have shown that students have positive attitudes towards interdisciplinary learning, and this leads to improved understanding of their roles on the healthcare team [20, 21]. In our Pharmacotherapeutics in Primary Care Selective, both medical and pharmacy students were able to work together during didactic sessions, case reviews, and clinical evaluation of patients in the hospital. Collaborative experiences with social work students were also integrated when possible during the post-discharge home visit portion of the curriculum. Our study affirmed that student confidence in collaborating with other healthcare team members was increased. Specifically, students reported improvements in their ability to work and learn from other health professionals while adapting their role as a member of the healthcare team.

While literature exists regarding incorporation of pharmacology education in medical school during the first and second years, there is limited literature that considers the combination of advanced training in pharmacotherapy with interdisciplinary education [22, 23]. Furthermore, certain authors point to the lack of clinical pharmacy faculty in academia as a hindrance in the ability to fully integrate this approach into medical school education [24]. We were able to address this problem by benefiting from a formal partnership (e.g., affiliation agreement) between the medical school and the pharmacy program that allowed our team to include pharmacy faculty throughout the development, application, and implementation of the selective. Our experience highlights an example of a model that can be implemented in other medical schools to incorporate meaningful interprofessional interactions to improve medical students’ pharmacotherapy knowledge and skills.

Limitations

While our curriculum demonstrated improvements in the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of medical students in this pharmacotherapy selective, there were a few limitations in our study. Due to additional selective experiences available to students rotating through family medicine, we were only able to include a small sample size of students (n = 68) for evaluation. Additionally, we did not use a validated survey. Rather, the knowledge and skills items of the assessment tool were developed to evaluate our objectives for the curriculum and to ensure that students were learning material specifically from the curriculum. The use of the same instrument for both the pre- and post-assessments may have also led to the potential for testing bias; however, potential carryover effects were limited by the 16-week washout period between the assessments. We did not conduct tests of homogeneity in our analyses; thus, it is possible that heterogeneity among cohorts may exist. Future analyses would benefit from cohort comparisons to ensure homogeneity.

Furthermore, we did not compare the enrolled students with other medical students who did not take the selective; thus, we cannot conclude that all the improvements seen in knowledge were solely due to the selective course. We also encountered challenges during the implementation of the curriculum. At times, it was difficult to align the schedules of the learners and patients for home visits; however, all cohorts were able to complete one home visit. Finally, we were not able to assess the impact of this selective on knowledge, attitudes, and skills of medical students as they progressed to later stages of their training and development (i.e., during residencies).

Conclusion

Current trends in medical school education indicate that there may be a need for increasing medical student exposure to pharmacotherapy education throughout their curriculum. Our longitudinal pharmacotherapy selective provides 3rd-year medical students with opportunities to improve their knowledge, attitudes, and skills related to the pharmacotherapeutic management of high-risk medications and patient populations while exploring meaningful interprofessional interactions with faculty and learners from other disciplines. This study highlights an example of how medical schools can advance traditional pharmacology education delivered during the pre-clinical years into application-based pharmacotherapy experiences during the clinical curriculum. Future opportunities also include evaluating the impact of pharmacotherapy curricula on important long-term outcomes such as improving patient safety through the reduction in prescription errors leading to adverse drug events.

Availability of Data and Material

Access to raw data analyzed in this manuscript is available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rosebraugh CJ, Honig PK, Yasuda SU, Pezzullo JC, Flockhart DA, Woosley RL. Formal education about medication errors in internal medicine clerkships. JAMA. 2001;286(9):1019–1020. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy JA, Shrader SR, Montooth AK. Outcomes of a pharmacotherapy/research rotation in a family medicine training program. Fam Med. 2008;40(6):395–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jorgenson D, Muller A, Whelan AM. Pharmacist educators in family medicine residency programs: a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2012:12–74. 10.1186/1472-6920-12-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bazaldua O, Ables AZ, Dickerson LM, et al. Suggested guidelines for pharmacotherapy curricula in family medicine residency training: recommendations from the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Group on Pharmacotherapy. Fam Med. 2005;37(2):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lesar TS, Lomaestro BM, Pohl H. Medication-prescribing errors in a teaching hospital. A 9-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1569–1576. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440350075007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medication error reports. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/medication-errors-related-cder-regulated-drug-products. Updated May 6, 2019. Accessed Jul 2, 2019.

- 7.Adverse drug events in adults. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/medicationsafety/adult_adversedrugevents.html. Updated October 11, 2017. Accessed Jun 26, 2019.

- 8.Cohen AL, Budnitz DS, Weidenbach KN, et al. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2008;152(3):416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh AK, Ghosh K. Misinterpretation of numbers: a potential source of physician's error. Lancet. 2004;364(9440):1108–1109. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2002–2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geller AI, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Hicks LA, Sapiano MRP, Budnitz DS. National estimates of emergency department visits for antibiotic adverse events among adults-United States, 2011–2015. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1060–1068. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4430-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of Medicine. 2007. Preventing medication errors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/11623.

- 13.Nierenberg DW. A core curriculum for medical students in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. The Council for Medical Student Education in Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48(6):606–610. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1990.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.QuickFacts: El Paso City, Texas. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/elpasocitytexas/PST045218. Updated July 1, 2019. Accessed Sep 9, 2019.

- 15.McLellan L, Tully MP, Dornan T. How could undergraduate education prepare new graduates to be safer prescribers? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(4):605–613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Candler C, Ihnat M, Huang G. Pharmacology education in undergraduate and graduate medical education in the United States. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82(2):134–137. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber N, Rawlins M, Franklin BD. Reducing prescribing error: competence, control, and culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2003;12(suppl 1):i29–i32. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_1.i29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall P, Weaver L. Interdisciplinary education and teamwork: a long and winding road. Med Educ. 2001;35(9):867–875. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morphet J, Hood K, Cant R, Baulch J, Gilbee A, Sandry K. Teaching teamwork: an evaluation of an interprofessional training ward placement for health care students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:197–204. Published 2014 Jun 25. 10.2147/AMEP.S61189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Fineberg IC, Wenger NS, Forrow L. Interdisciplinary education: evaluation of a palliative care training intervention for pre-professionals. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):769–776. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindquist LA, Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Doeksen A, Liss D. Teaching medication reconciliation through simulation: a patient safety initiative for second year medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):998–1001. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivam SP, Iatridis PG, Vaughn S. Integration of pharmacology into a problem-based learning curriculum for medical students. Med Educ. 1995;29(4):289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naritoku DK, Faingold CL. Development of a therapeutics curriculum to enhance knowledge of fourth-year medical students about clinical uses and adverse effects of drugs. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):148–152. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Access to raw data analyzed in this manuscript is available upon request.