Abstract

Background and Aims

The recognition of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) failure/refractoriness among Chinese clinicians remains unclear. Using an online survey conducted by the Chinese College of Interventionalists (CCI), the aim of this study was to explore the recognition of TACE failure/refractoriness and review TACE application for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatment in clinical practice.

Methods

From 27 August 2020 to 30 August 2020 during the CCI 2020 annual meeting, a survey with 34 questions was sent by email to 264 CCI clinicians in China with more than 10 years of experience using TACE for HCC treatment.

Results

A total of 257 clinicians participated and responded to the survey. Most participants agreed that the concept of “TACE failure/refractoriness” has scientific and clinical significance (n=191, 74.3%). Nearly half of these participants chose TACE-based combination treatment as subsequent therapy after so-called TACE failure/refractoriness (n=88, 46.1%). None of the existing TACE failure/refractoriness definitions were widely accepted by the participants; thus, it is necessary to re-define this concept for the treatment of HCC in China (n=235, 91.4%). Most participants agreed that continuing TACE should be performed for patients with preserved liver function, presenting portal vein tumor thrombosis (n=242, 94.2%) or extrahepatic spread (n=253, 98.4%), after the previous TACE treatment to control intrahepatic lesion(s).

Conclusions

There is an obvious difference in the recognition of TACE failure/refractoriness among Chinese clinicians based on existing definitions. Further work should be carried out to re-define TACE failure/refractoriness.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, TACE, Failure, Refractoriness, Survey

Introduction

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) plays a key role in the management of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).1–4 According to the global BRIDGE study, TACE is the most widely applied approach in both intermediate and advanced stages of HCC, as recommended by several guidelines.5 Considering the epidemiological differences between countries, HCC patients in China treated with TACE are often reported to have a higher tumor burden compared to those in Western countries.6 The purpose of TACE for HCC is to control or shrink the lesion(s) locally. Due to the high heterogeneity of HCC, which varies according to the number, size, location, and growth pattern of tumors, it is difficult to achieve a satisfactory tumor response from a single session of TACE.7,8 However, repeated TACE could damage liver function and increase treatment-related side effects.9 Therefore, a delicate balance between the necessity and benefits of repeated TACE treatment should be considered, where benefits are also balanced against treatment side effects.

To assess such balance in clinical practice and clinical trials, several organizations and panels, including the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) (Kyoto, Japan), the International Association for the Study of the Liver (Shanghai, China), and a European expert panel, introduced various definitions of TACE failure/refractoriness.10–12 Among them, the 2014 definition by the JSH-Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan (LCSGJ) is most widely applied in clinical practice and trials. According to JSH-LGSGJ 2014 criteria, the incidence of TACE failure/refractoriness ranges from 37.0% to 49.3%.13,14

Nevertheless, by emphasizing retrospective studies and consensus rather than high-level evidence, these definitions and subsequent treatment recommendations for TACE failure/refractoriness remain somewhat ambiguous and controversial. In addition, the epidemiological difference in research between Japan/Western countries and China reveals discrepancies in the extent of disease burden, whereby a relatively higher burden of HCC is reported in China. Under these circumstances, three questions remain to be answered before the definitions and subsequent treatment recommendations can be applied in China. (1) Is TACE failure/refractoriness widely accepted and applied in real-world clinical practice in China? (2) Is the definition-recommended subsequent treatment after TACE failure/refractoriness accepted and applied in real-world clinical practice in China? (3) What are the ideal definition and subsequent treatment recommendations of TACE failure/refractoriness in China?

The Chinese College of Interventionalists (CCI) conducted an online survey to identify the trends in real-world clinical practice of TACE, recognition of TACE failure/refractoriness, and subsequent treatment strategies in China.

Methods

Study population and questionnaire

The present study did not require an approval from an institutional review board, because it was solely based on reported statistics and did not involve humans or animals as subjects. The TACE procedure mentioned in this survey was conventional TACE. During the CCI 2020 annual meeting from 27 August 2020 to 30 August 2020, the questionnaires were sent by email to 264 clinicians with more than 10 years of experience in using TACE for HCC treatment in China. On 28 August 2020 and 30 August 2020, follow-up telephone calls were made to the nonresponders and to the responders who did not fill out the questionnaires completely, respectively.

The questionnaire was designed and formulated with four major parts: (1) the overall understanding of TACE in real-world clinical practice; (2) factors influencing the treatment response of TACE; (3) understanding and expectations of TACE failure/refractoriness and subsequent treatment patterns; and (4) perspectives on TACE.

Completed questionnaires returned before 31 August 2020 were collected for analysis. Questionnaires returned after 30 August 2020 and incomplete questionnaires were excluded.

Statistical analysis

The data, including number and proportion of every question, were collected and calculated with the SPSS version 22.0 software for Windows (IBM Corporation, Somers, New York).

Results

Participants

Three participants did not respond, and four participants sent back incomplete questionnaires and did not revise them even after our telephone calls. A total of 257 clinicians from 184 hospitals participated and responded correctly to the survey, with a response rate of 97.3%. The participating clinicians included 196 interventional radiologists, 37 oncologists, 16 gastroenterologists, and 8 surgeons. More than half of the included clinicians (n=156, 61%) were chief physicians/professors, and the remaining 101 (39%) were associate chief physicians/associate professors. All of the participating physicians routinely discuss HCC treatment in the local tumor board of their hospitals. The locations of the participating clinicians’ hospitals covered all 31 provinces in China. A total of 34 questions were included in the survey (supplementary Table 1).

Overall understanding of TACE in real-world clinical practice

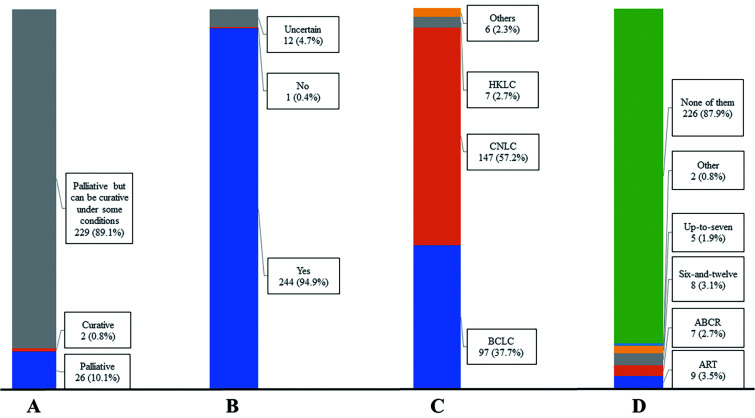

In this part, the survey included the eight single-choice questions (Figs. 1 and 2). Most clinicians (n=229, 89.1%) agreed that TACE acts as a palliative treatment but can achieve curative effects under certain conditions. Despite various treatment outcomes of TACE, clinicians still choose TACE as the first choice for intermediate stage HCC treatment. TACE combined with other approaches might achieve better treatment outcomes (n=251, 97.7%). The guidelines of the China Liver Cancer (CNLC) were followed by most participants (n=147, 57.2%) for TACE application in clinical practice, and none of the current scoring systems are effective in guiding TACE treatment.15 Therefore, participants agreed that there is a need to subgroup the intermediate stage HCC in the current guidelines, since none of the existing subclassification systems are widely accepted.

Fig. 1. Answers to questions 1–4 about the overall understanding of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in the real-world clinical practice.

(A) Q1, most participants (n=229, 89.1%) agreed that TACE acts as a palliative method, but can achieve curative outcomes under some conditions. (B) Q2, most participants (n=244, 94.9%) agreed that treatment outcomes of TACE have a high variation. (C) Q3, more than half of the participants (n=147, 57.2%) followed the CNLC staging system for TACE application. (D) Q4, most participants (n=226, 87.9%) agreed that none of the scoring systems are suitable to assess and predict treatment benefits for initial or repeated TACE. HKLC, Hong Kong Liver Cancer; CNLC, China National Liver Cancer; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer.

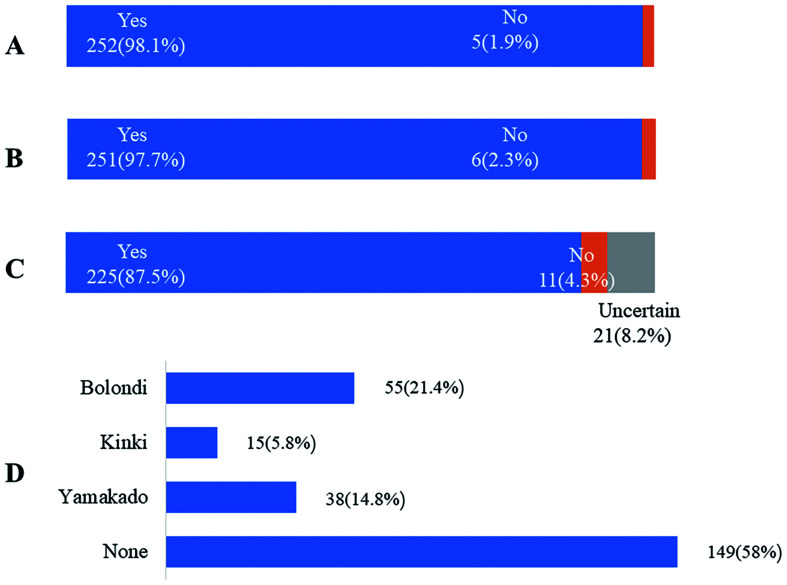

Fig. 2. Answers to questions 5–8 about the overall understanding of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in the real-world clinical practice.

(A) Q5, 252 participants (98.11%) agreed that TACE is still the first choice for intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). (B) Q6, 251 participants (97.7%) agreed that TACE combined with other approaches could achieve a better treatment outcome. (C) Q7, 225 participants (87.5%) agreed that there is a need to subgroup intermediate stage HCC in the current guidelines. (D) Q8, 149 participants (58.0%) agreed that none of the current subgroups are suitable for intermediate stage HCC.

Factors influencing treatment response of TACE

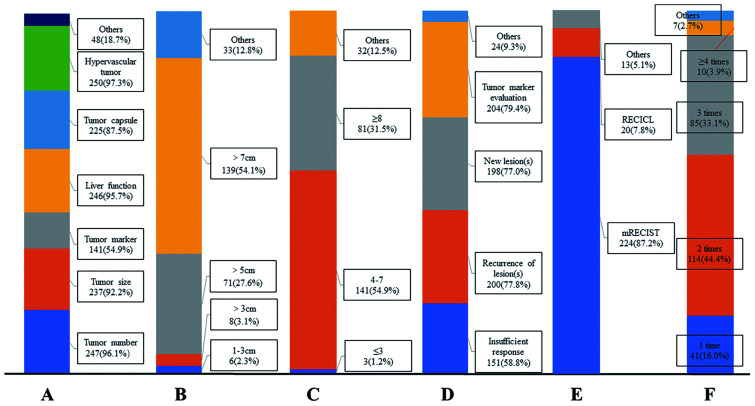

In this part, the survey included six single- or multiple-choice questions (Fig. 3). Most clinicians agreed that multiple factors, including the tumor burden, tumor morphology, and liver function, are associated with treatment response to TACE. More than half of the participants (n=139, 54.1%) reported that it is difficult to achieve a satisfactory response after TACE for tumor lesion(s) larger than 7 cm in diameters. Similarly, more than half of the participants (n=141, 54.9%) reported that a good tumor response after TACE is hard to achieve for patients with more than three tumor lesions. Most participants (n=224, 87.2%) agreed that the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST) is the best criteria to assess tumor response after TACE, and at least two or three sessions of TACE should be performed before assessing comprehensive treatment outcome.

Fig. 3. Answers to questions 9–14 about factors influencing treatment response of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE).

(A) Q9, multiple variables affect the treatment outcome of TACE. (B) Q10, the majority of participants (n=139, 54.1%) agreed that it is difficult to achieve a satisfied tumor response after TACE for lesion(s) with diameters larger than 7.00 cm. (C) Q11, most participants (n=141, 54.9%) agreed that it is difficult to achieve a satisfied tumor response after TACE for 4–7 target lesion(s) (D) Q12, multiple variables predict an unsatisfied treatment outcome of TACE. (E) Q13, most participants (n=224, 87.2%) agreed that mRECIST is the most suitable tool to assess tumor response after TACE. (F) Q14, 114 participants (44.4%) agreed that at least two sessions of TACE should be performed before assessing the comprehensive treatment outcome. RECICL, Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the Liver; mRECIST, Modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Understanding and expectations of TACE failure/refractoriness and subsequent treatment pattern

In this part, the survey included 17 single- or multiple-choice questions (Supplementary Figs. 1–6). Most participants (n=221, 86.0%) agreed that repeated TACE should be performed even if incomplete tumor necrosis was not achieved after the previous super-selective TACE. Of the 221 participants, most (n=166, 75.1%) believed that repeated TACE should be performed only if new tumor arteries appear and super-selective TACE could be provided. A proportion of participants (n=106, 41.2%) disagreed that the “occurrence of two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor” should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness. For these participants, TACE-based combination therapy ranked first (n=84, 79.2%) as the ideal subsequent therapy. Moreover, nearly one third of participants (n=75, 29.2%) chose three consecutive treatments of insufficient TACE sessions as the most ideal number to define TACE failure/refractoriness. Nearly half of the participants (n=121, 47.1%) disagreed that “new intrahepatic lesion(s)” should be considered as TACE failure/refractoriness, while only 16.3% of the participants chose the opposite answer. The majority of the above-mentioned participants (n=93, 76.9%) who answered “No” to the “new intrahepatic lesion(s)” question considered combination therapy, including TACE, as the ideal subsequent therapy. Of the participants who answered “Yes”, half of them (n=21, 50.0%) considered “3 consecutive times of new intrahepatic lesion(s) should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness.”

Most participants agreed that repeated TACE should be performed to control intrahepatic lesion(s) for patients with preserved liver function, who developed portal vein tumor thrombosis (PVTT) (n=242, 94.2%) or extrahepatic spread (n=253, 98.4%) following TACE. Multiple treatments are also recommended as a combination approach with TACE to control PVTT or extrahepatic spread. More than half of the participants (n=165, 64.2%) agreed that continuous elevation of tumor markers, such as alpha fetoprotein and Protein Induced by Vitamin K Absence or Antagonist-II immediately after TACE, should be considered as TACE failure/refractoriness.

Most participants (n=191, 74.3%) agreed that the concept of TACE failure/refractoriness has scientific and clinical significance. However, current existing definitions are not suitable for clinical practice in the real-world and need to be re-defined, especially for the treatment of HCC patients in China (n=235, 91.4%). For participants who accepted the concept of TACE failure/refractoriness, “combination treatment including TACE” ranked first (n=88, 46.1%) as the ideal subsequent treatment after TACE failure/refractoriness.

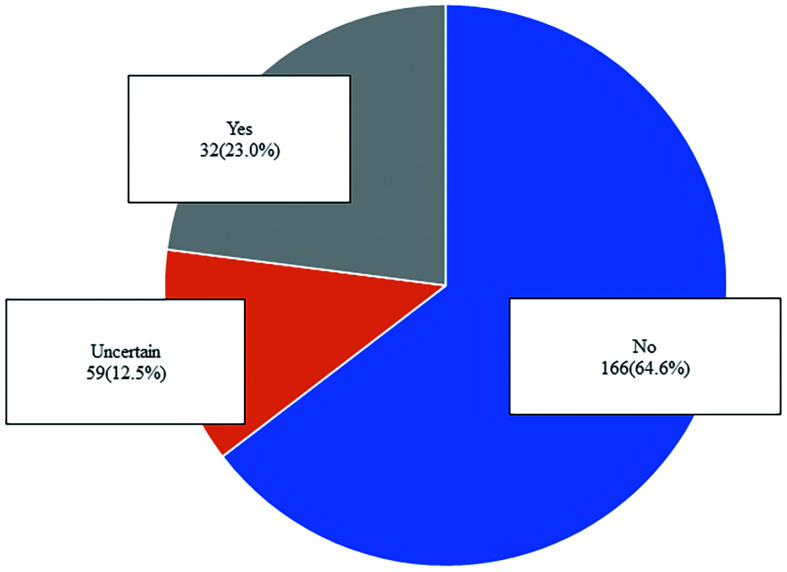

Perspectives on TACE

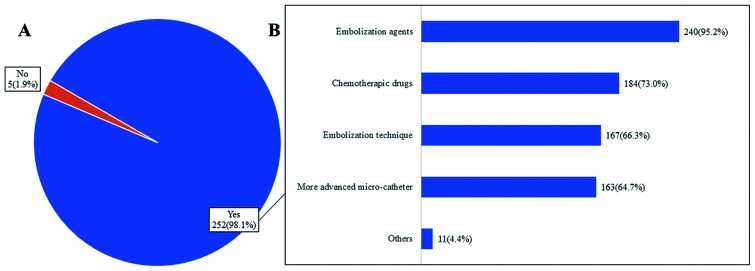

In this part, the survey included the three single- or multiple-choice questions (Figs. 4 and 5). More than half of the participants (n=166, 64.6%) did not think that the number of TACE sessions would decrease in clinical practice in the future. Most of the participants (n=252, 98.1%) believed that the TACE technique would be improved in the future with more advanced embolic agents, chemotherapeutic drugs, embolization technique, and micro-catheters.

Fig. 4. Answers to questions 32 about predictions for future transarterial chemoembolization the number of (TACE).

More than half of the participants (n=166, 64.6%) agreed that the number of TACE sessions would not decrease in clinical practice in the future.

Fig. 5. Answers to questions 33–34 about perspectives on transarterial chemoembolization (TACE).

(A) Q33, almost all participants (n=252, 98.1%) agreed that the TACE technique would be improved in the future. (B) Q34, participants agreed that multiple aspects of the TACE technique would be improved.

Discussion

In clinical practice, it is critical to establish a balance between the potential treatment benefits and liver function impairment of repeated TACE. To do so, the concept of “TACE failure/refractoriness” should be considered carefully, especially since the real-world clinical applicability of the existing definitions and subsequent recommended therapies is under debate in China. Therefore, the CCI survey was conducted to identify how clinicians specialized in HCC treatment in China apply TACE, and their opinions about the concept of “TACE failure/refractoriness”. Results reveal that the majority of the participating clinicians accept the concept of TACE failure/refractoriness, which has scientific and clinical significance. Moreover, the participants believe that the current existing definitions are not suitable and need to be re-defined, especially for HCC treatment in real-world clinical practice in China.

Because of the high heterogeneity of HCC, the prognosis of patients treated with TACE varies from a median survival of 19.4 months to around 49.1 months.16,17 Therefore, several subclassifications and predictive scoring systems have been established to subclassify ideal candidates receiving initial or repeated TACE.7,8,18-21 Among them, the criteria proposed by Bolondi and Kinki is based on the tumor burden (up-to-seven criteria) and liver function to stratify patients who would benefit from initial TACE.7,8 The Assessment for Retreatment with TACE (ART) score is based on pre-procedural liver function, including the Child-Pugh score and serum aspartate aminotransperase, and tumor response evaluation after initial TACE to determine whether repeated TACE would still be beneficial.20 Nevertheless, none of these subclassifications or scoring systems have been widely accepted or applied in clinical practice, which is further confirmed by the results of this survey . The existing definitions consider the concept of TACE failure/refractoriness as consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor and new intrahepatic lesion(s); thus, it is used to better assess the benefit of repeated TACE. While the JSH-LCSGJ 2014 criteria define two consecutive insufficient responses or two consecutive new intrahepatic lesion(s) as TACE failure/refractoriness, the present survey revealed different opinions. A larger proportion of participants (n=106, 41.2%) did not think that “two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor occurs” should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness, while a smaller proportion (n=85, 33.1%) agreed with such definition. In addition, a larger proportion of participants (n=75, 29.2%) believed that three consecutive insufficient responses should be considered as TACE failure/refractoriness, while a smaller proportion (n=74, 28.8%) agreed with two consecutive insufficient responses. Similar responses were also observed for the definition regarding new intrahepatic lesions that occur after TACE. The majority of participants disagreed that new intrahepatic lesion(s) after TACE should be considered as TACE failure/refractoriness compared to one-third of that majority who agreed with such definition. Instead of sorafenib that is recommended by the existing TACE failure/refractoriness definitions, TACE-based combination therapy ranked first as the ideal subsequent therapy after two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor or new intrahepatic lesion(s).

All existing definitions regard the presence of PVTT or extrahepatic spread after TACE as TACE failure/refractoriness, and recommend witching to sorafenib. In contrast, the current survey showed that most participants believe continuing TACE is necessary to control intrahepatic lesion(s) for HCC patients with preserved liver function who presented PVTT or extrahepatic spread after the previous TACE. Certainly, combination therapies, including molecular targeted therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, I125 seeds implantation, and ablation, with TACE are recommended by the participants to control PVTT/extrahepatic spread. Considering the fatality of more than two-thirds of patients with advanced HCC due to intrahepatic tumor progression or liver failure instead of metastatic disease progression, TACE targeting the intrahepatic lesion(s) would be a reasonable and beneficial treatment for advanced HCC. Many previous studies have demonstrated the treatment efficacy and safety of TACE monotherapy or TACE combined with sorafenib in advanced HCC patients with PVTT or extrahepatic spread.22–26

Apart from the topic on TACE failure/refractoriness, the survey was also conducted to determine the understanding of TACE in real-world clinical practice, factors influencing treatment response, and perspectives on TACE. Most of the participants agreed that tumor burden, tumor morphology, and liver function are the major factors associated with tumor response. They also agreed that a subclassification of the intermediate stage is needed. This might be the reason that the existing subclassification systems or prognostic score systems for HCC are not widely accepted in clinical practice, especially in China.

Limitations

The study has several limitations, although it reveals the present recognition of TACE failure/refractoriness and could promote a more standardized application of TACE in clinical practice in China. First, more than half of the participants are interventional radiologists. More participants from the department of oncology, gastroenterology, surgery, et al. should be included to avoid selection bias. Second, the study did not introduce a new definition of TACE failure/refractoriness. Further meetings and study should be carried out to introduce the modified criteria of TACE failure/refractoriness. Third, the survey was carried out in the mainland of China and did not include participants from other countries, which might limit the readership interest around the world.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the survey conducted by CCI demonstrates an obvious difference in the recognition of TACE failure/refractoriness in HCC treatment between Chinese experts when compared to the existing definitions. Re-defining the criteria for TACE failure/refractoriness and introducing the subclassification for intermediate stage HCC are warranted to better select HCC patients who will benefit most from TACE and to optimize treatment strategies for HCC.

Supporting information

(A) Q15, the highest percentage of participants (n=90, 35%) believed that TACE failure/refractoriness needs to be redefined. (B) Q16, the majority of participants (n=221, 86%) agreed that repeated TACE should be performed if sufficient tumor necrosis did not achieve after previous super-selective TACE. (C) Q17, most participants (n=166, 75.1%) agreed that whether to trigger the next TACE session depends on the feeding arteries of the residual tumor. LCSGJ, Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan.

(A) Q18, nearly half of the participants (n=106, 41.2%) agreed that “two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor” should not be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness. (B) Q19, among participants who disagreed that TACE failure/refractoriness should be defined as “two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor occur”, TACE-based combination treatment is mostly preferred for the unsatisfactorily-controlled target lesion(s). (C) Q20, the highest number of participants (n=75, 29.8%) suggested that three consecutive times of insufficient responses of the target tumor should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

(A) Q21, 121 participants (47.1%) believed that new intrahepatic lesion(s) should not be considered as TACE failure/refractoriness? (B) Q22, for participants who chose “Yes” in Q21, half of them (n=21, 50.0%) agreed that three consecutive times of intrahepatic lesion(s) occurrence should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness? (C) Q23, for participants who chose “No” in Q21, most of them (n=93, 76.9%) agreed that TACE-based combination treatment is preferred for the new intrahepatic lesion(s). TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

(A) Q24, 242 participants (94.2%) agreed that continue TACE to control intrahepatic lesion(s) should be performed if segmental portal vein tumour thrombosis (PVTT) occurs with preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A/B) after previous TACE. (B) Q25, participants agreed that multiple combination therapy should be considered to control PVTT. PVTT, portal vein tumour thrombosis; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

(A) Q26, 253 participants (98.5%) agreed that continue TACE to control intrahepatic lesion(s) should be performed if extrahepatic spread occurs with preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A/B) after previous TACE. (B) Q27, participants agreed that multiple combination therapy should be considered to control extrahepatic spread. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

(A) Q29, 199 participants (74.3%) agreed that the concept of “TACE failure/refractoriness” has its scientific and clinical significance. (B) Q30, nearly half of the participants (n=88, 46.1%) suggested that TACE-based combination treatment is preferred to perform after TACE failure/refractoriness. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Abbreviations

- CCI

Chinese College of Interventionalists

- CNLC

China liver cancer

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- JSH

Japan Society of Hepatology

- LCSGJ

Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan

- mRECIST

modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors

- PVTT

portal vein tumor thrombosis

- TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1301–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(15):1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–750. doi: 10.1002/hep.29913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE study. Liver Int. 2015;35(9):2155–2166. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J, Sun HC, Wang Z, Cong WM, Wang JH, Zeng MS, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer in China (2017 Edition) Liver Cancer. 2018;7(3):235–260. doi: 10.1159/000488035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolondi L, Burroughs A, Dufour JF, Galle PR, Mazzaferro V, Piscaglia F, et al. Heterogeneity of patients with intermediate (BCLC B) hepatocellular carcinoma: proposal for a subclassification to facilitate treatment decisions. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32(4):348–359. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudo M, Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Sakurai T, Kitano M, Nishida N. Subclassification of BCLC B stage hepatocellular carcinoma and treatment strategies: proposal of modified Bolondi’s subclassification (Kinki Criteria) Dig Dis. 2015;33(6):751–758. doi: 10.1159/000439290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogl TJ, Trapp M, Schroeder H, Mack M, Schuster A, Schmitt J, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: volumetric and morphologic CT criteria for assessment of prognosis and therapeutic success-results from a liver transplantation center. Radiology. 2000;214(2):349–357. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe06349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudo M, Matsui O, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Okusaka T, Miyayama S, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization failure/refractoriness: JSH-LCSGJ criteria 2014 update. Oncology. 2014;87(Suppl 1):22–31. doi: 10.1159/000368142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JW, Amarapurkar D, Chao Y, Chen PJ, Geschwind JF, Goh KL, et al. Consensus recommendations and review by an international expert panel on interventions in hepatocellular carcinoma (EPOIHCC) Liver Int. 2013;33(3):327–337. doi: 10.1111/liv.12083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raoul JL, Gilabert M, Piana G. How to define transarterial chemoembolization failure or refractoriness: a European perspective. Liver Cancer. 2014;3(2):119–124. doi: 10.1159/000343867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byun J, Kim SY, Kim JH, Kim MJ, Yoo C, Shim JH, et al. Prediction of transarterial chemoembolization refractoriness in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using imaging features of gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0284185120971844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu K, Lu S, Li M, Zhang F, Tang B, Yuan J, et al. A novel pre-treatment model predicting risk of developing refractoriness to transarterial chemoembolization in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2020;11(15):4589–4596. doi: 10.7150/jca.44847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, Cong W, Wang J, Zeng M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2019 Edition) Liver Cancer. 2020;9(6):682–720. doi: 10.1159/000509424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lencioni R, de Baere T, Soulen MC, Rilling WS, Geschwind JF. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):106–116. doi: 10.1002/hep.28453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Xia D, Bai W, Wang E, Sun J, Huang M, et al. Development of a prognostic score for recommended TACE candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre observational study. J Hepatol. 2019;70(5):893–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kadalayil L, Benini R, Pallan L, O’Beirne J, Marelli L, Yu D, et al. A simple prognostic scoring system for patients receiving transarterial embolisation for hepatocellular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2565–2570. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park Y, Kim SU, Kim BK, Park JY, Kim DY, Ahn SH, et al. Addition of tumor multiplicity improves the prognostic performance of the hepatoma arterial-embolization prognostic score. Liver Int. 2016;36(1):100–107. doi: 10.1111/liv.12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sieghart W, Hucke F, Pinter M, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Müller C, et al. The ART of decision making: retreatment with transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2261–2273. doi: 10.1002/hep.26256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adhoute X, Penaranda G, Naude S, Raoul JL, Perrier H, Bayle O, et al. Retreatment with TACE: the ABCR SCORE, an aid to the decision-making process. J Hepatol. 2015;62(4):855–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu K, Chen J, Lai L, Meng X, Zhou B, Huang W, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombus: treatment with transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib—a retrospective controlled study. Radiology. 2014;272(1):284–293. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinter M, Hucke F, Graziadei I, Vogel W, Maieron A, Königsberg R, et al. Advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization versus sorafenib. Radiology. 2012;263(2):590–599. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi GH, Shim JH, Kim MJ, Ryu MH, Ryoo BY, Kang YK, et al. Sorafenib alone versus sorafenib combined with transarterial chemoembolization for advanced-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results of propensity score analyses. Radiology. 2013;269(2):603–611. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung GE, Lee JH, Kim HY, Hwang SY, Kim JS, Chung JW, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization can be safely performed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma invading the main portal vein and may improve the overall survival. Radiology. 2011;258(2):627–634. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chern MC, Chuang VP, Liang CT, Lin ZH, Kuo TM. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: safety, efficacy, and prognostic factors. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Q15, the highest percentage of participants (n=90, 35%) believed that TACE failure/refractoriness needs to be redefined. (B) Q16, the majority of participants (n=221, 86%) agreed that repeated TACE should be performed if sufficient tumor necrosis did not achieve after previous super-selective TACE. (C) Q17, most participants (n=166, 75.1%) agreed that whether to trigger the next TACE session depends on the feeding arteries of the residual tumor. LCSGJ, Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan.

(A) Q18, nearly half of the participants (n=106, 41.2%) agreed that “two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor” should not be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness. (B) Q19, among participants who disagreed that TACE failure/refractoriness should be defined as “two consecutive insufficient responses of the target tumor occur”, TACE-based combination treatment is mostly preferred for the unsatisfactorily-controlled target lesion(s). (C) Q20, the highest number of participants (n=75, 29.8%) suggested that three consecutive times of insufficient responses of the target tumor should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

(A) Q21, 121 participants (47.1%) believed that new intrahepatic lesion(s) should not be considered as TACE failure/refractoriness? (B) Q22, for participants who chose “Yes” in Q21, half of them (n=21, 50.0%) agreed that three consecutive times of intrahepatic lesion(s) occurrence should be defined as TACE failure/refractoriness? (C) Q23, for participants who chose “No” in Q21, most of them (n=93, 76.9%) agreed that TACE-based combination treatment is preferred for the new intrahepatic lesion(s). TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

(A) Q24, 242 participants (94.2%) agreed that continue TACE to control intrahepatic lesion(s) should be performed if segmental portal vein tumour thrombosis (PVTT) occurs with preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A/B) after previous TACE. (B) Q25, participants agreed that multiple combination therapy should be considered to control PVTT. PVTT, portal vein tumour thrombosis; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

(A) Q26, 253 participants (98.5%) agreed that continue TACE to control intrahepatic lesion(s) should be performed if extrahepatic spread occurs with preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A/B) after previous TACE. (B) Q27, participants agreed that multiple combination therapy should be considered to control extrahepatic spread. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

(A) Q29, 199 participants (74.3%) agreed that the concept of “TACE failure/refractoriness” has its scientific and clinical significance. (B) Q30, nearly half of the participants (n=88, 46.1%) suggested that TACE-based combination treatment is preferred to perform after TACE failure/refractoriness. TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.