Abstract

Background and Aims

Previous studies reported that serum resistin levels were remarkably changed in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) but the conclusions were inconsistent. The aim of this study was to investigate accurate serum resistin levels in adult patients with NAFLD.

Methods

A complete literature research was conducted in the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases, and all the available studies up to 7 May 2020 were reviewed. The pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) values were calculated to investigate the serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD and healthy controls.

Results

A total of 28 studies were included to investigate the serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD. Patients with NAFLD had higher serum resistin levels than controls (SMD=0.522, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.004–1.040, I2=95.9%). Patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) had lower serum resistin levels than the healthy controls (SMD=−0.44, 95% CI: −0.83–0.55, I2=74.5%). In addition, no significant difference of serum resistin levels was observed between patients with NAFL and healthy controls (SMD=−0.34, 95% CI: −0.91–0.23, I2=79.6%) and between patients with NAFL and NASH (SMD=0.15, 95% CI: −0.06–0.36, I2=0.00%). Furthermore, subgroup and sensitivity analyses suggested that heterogeneity did not affect the results of meta-analysis.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis investigated the serum resistin levels in adult patients with NAFLD comprehensively. Patients with NAFLD had higher serum resistin levels and patients with NASH had lower serum resistin levels than healthy controls. Serum resistin could serve as a potential biomarker to predict the development risk of NAFLD.

Keywords: Resistin, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Biomarker

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as hepatic steatosis by imaging or histology without secondary factors of hepatic fat aggregation, such as significant alcohol consumption and long-term use of a steatogenic medication.1 NAFLD ranges from nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), which is characterized as simple benign hepatic steatosis, to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the histologic features of which are macrovesicular steatosis, hepatocellular ballooning, lobular inflammation, and pericellular fibrosis. NASH can progress to the more severe fibrosis, that is defined as the accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins in the liver interstitial space, cirrhosis, and even the hepatocellular carcinoma.2 Nowadays, NASH-associated cirrhosis has become the second leading cause for liver transplantation in the USA. Meanwhile, NAFLD increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease.3

NAFLD has been certainly become the most predominant chronic liver disease in the world, with the highly shocking prevalence of 25.24% among the global population. In fact, the prevalence is predicted to become even higher in the next decade.4 Up to now, the diagnostic golden standard for NAFLD is liver biopsy. As an invasive technology, some adverse events can occur during liver biopsy diagnosis of patients, such as pain, infection, bleeding and even death.5 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a novel biomarker to predict and diagnose NAFLD conveniently and accurately.

Resistin belongs to the family of resistin-like molecules, also known as “found in inflammatory zone” (FIIZ), and functions as a pro-inflammatory adipokine.6 Resistin is mainly produced by adipose tissue, inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and monocytes, and hepatic stellate cells.7 Previous reports have suggested that resistin could be up-regulated by proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β. In turn, resistin can activate the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway and promote the synthesis of TNF-α, IL-6 and other pro-inflammatory agents.8

Regarding the association of serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD, the studies showed conflicting results so far. Some researchers have reported that serum resistin levels are high in patients with NAFLD, NAFL, and NASH compared to healthy subjects.9 However, other researchers have suggested that no significant difference exists for serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD, NAFL, NASH, and healthy controls.10,11 In the comparison between patients with NASH and NAFL, some studies have found higher serum resistin levels in patients with NASH, whereas others studies found similar levels of serum resistin in patients with NASH and NAFL.10–12 Meanwhile, some researchers have reported lower serum resistin levels in patients with NASH compared to patients with NAFL or healthy controls.10,13

In consideration of the inconsistence of serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD, it is worthwhile to investigate the exact performance of serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD according to the available studies. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the available studies and comprehensively analyze the relationship between serum resistin levels and the degree of NAFLD.

Methods

Search strategy

To obtain the relevant studies for this meta-analysis, a complete literature search was conducted in the databases of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library by the following strategy: ((((((((((((((Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease) OR Non alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease) OR NAFLD) OR Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease) OR Fatty Liver, Nonalcoholic) OR Fatty Livers, Nonalcoholic) OR Liver, Nonalcoholic Fatty) OR Livers, Nonalcoholic Fatty) OR Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver) OR Nonalcoholic Fatty Livers) OR Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis) OR Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitides) OR Steatohepatitides, Nonalcoholic) OR Steatohepatitis, Nonalcoholic) AND (Resistin) OR Adipocyte Cysteine-Rich Secreted Protein FIIZ3) OR Adipocyte Cysteine Rich Secreted Protein FIIZ3. All the potentially relevant studies in English language and published before 7 May 2020 were reviewed. In case of data missed, we tried to contact the corresponding authors to obtain the original data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Clinical studies which performed comparison of serum resistin levels between NAFLD (NAFL or NASH) patients and healthy controls were suitable for this meta-analysis. Studies were included if they conformed to the following criteria: (1) original full-text publications; (2) NAFLD diagnosed with biopsy, ultrasound, liver enzymes or computerized tomography; and (3) serum resistin levels compared. Studies were excluded according to the following principles: (1) patients with other causes of chronic liver disease (alcoholic fatty liver disease, viral or autoimmune hepatitis); (2) subjects included in more than one study; (3) some necessary data missing and not obtainable from the authors; (4) quality of publication too low; (5) reviews, editorials, case reports, letters, hypotheses, book chapters, studies on animals or cell lines, and unpublished data or abstracts; or (6) participants with other medical conditions, such as diabetes and coronary heart disease.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (HDL and CJ) evaluated each article and extracted the data independently. The controversy was solved by discussion with a third author (LSS). The study quality was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS), as approved by the Cochrane Collaboration. The NOS uses a star system to decide the quality of a study in three realms: collection, comparability, and outcome/exposure. The NOS assigns four stars for selection, two stars for comparability, and three stars for outcome/exposure. Any study that received a score of 6 or more stars was regarded as being at low risk of bias (the highest quality), and lesser stars indicated a risk of bias.14

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using Stata/SE 15.0. Serum resistin levels in the NAFLD group and controls were extracted as mean difference±standard deviation (SD) and the pooled values were expressed as standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Forest plots were constructed to evaluate the heterogeneity of included studies by I2 statistic. According to Higgins and Thompson, I2 values of approximately 25% represented low heterogeneity, approximately 50% represented medium heterogeneity, and approximately 75% represented high heterogeneity. In this meta-analysis, continuous-weighted fixed-effects model analysis was used when the I2≤50%. Otherwise, the random-effects model was used. The possibility of publication bias was evaluated using funnel plot and the Egger’s regression asymmetry test. The sensitivity analysis, subgroup analysis, and meta-regression analysis were conducted to explore the possible sources of (expected) heterogeneity among the eligible studies. The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the quality of the pooled results of serum resistin levels in the NAFLD group vs. controls, NASH group vs. controls, NAFL group vs. controls, and NAFL group vs. NASH group.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

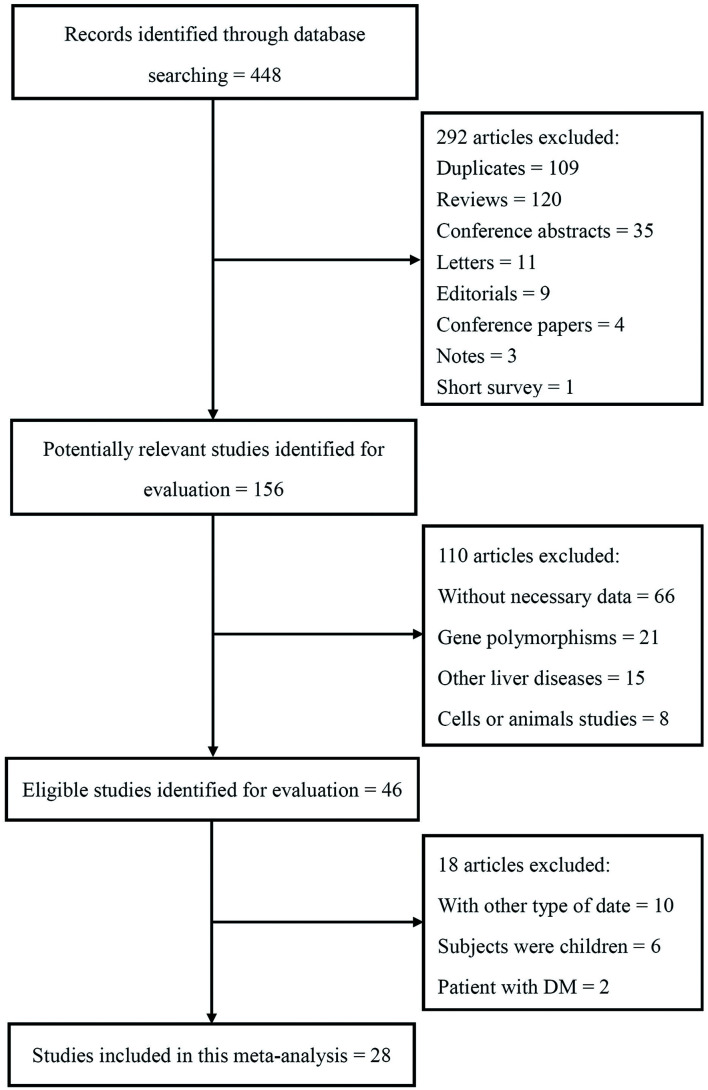

According to the search strategy, a total of 448 studies were obtained ((PubMed (n=103), Cochrane (n=328), and Embase (n=13)). After removing 109 duplicates, 339 articles were retrieved. After removing reviews, conference abstracts, letters, editorials, conference papers, notes and short surveys, 159 potential studies were retrieved. After full-text evaluation, 28 studies were included eventually for this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the literature search process.

The main characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. All the included studies were cross-sectional or case-control studies. Patients with NAFLD in 22 studies9,10,12,15–33 were assessed by liver histology, and 5 studies34–38 evaluated NAFLD by ultrasonography. One study did not specifically describe the diagnosis of NAFLD.39 Among these studies, 10 were carried out in Asia, 6 in North America, and 10 in Europe. Two studies were carried out in South America. Among the 28 included studies, 25 had no the risk of bias and 3 had risk of bias.

Table 1. Main characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| First author, Year | Group | n (M/F) | Age in years | BMI in kg/m2 | Country | Study design | Diagnose of NAFLD | Biopsy on controls | Measurement method of resistin | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentou et al. 200910 | Control | 9 (2/7) | 37.11±9.78 | 55.22±8.6 | Greece | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 8 |

| NAFLD | 41 (15/26) | 38.88±9.19 | 56.70±8.06 | |||||||

| SS | 31 (9/22) | 38.06±9.23 | 56.27±8.45 | |||||||

| NASH | 10 (6/4) | 41.04±9.07 | 58.02±6.99 | |||||||

| Auguet et al. 201320 | Control | 19 | 44.1±10.7 | 49.5±7.0 | Spain | Case-control | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 6 |

| NAFLD | 69 | 46.79±10.3 | 48.2±6.6 | |||||||

| Auguet et al. 201426 | Control | 16 | 44±3.2 | 48.6±2.6 | Spain | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 7 |

| SS | 28 | 47.4±3.5 | 48.1±7.8 | |||||||

| NASH | 28 | 45.9±1.4 | 47.5±5.4 | |||||||

| Bostrom et al. 201119 | Control | 40 (10/30) | 44 (24–67) | NA | Sweden | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 4 |

| NAFLD | 50 (37/13) | 48 (24–65) | NA | |||||||

| Pagano et al. 200615 | Control | 33 (30/3) | 42±3 | 26.9±1.0 | Italy | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 8 |

| NAFLD | 28 (26/2) | 45±2 | 27.3±0.6 | |||||||

| Cengiz et al. 201018 | Control | 24 | 38±10 | 25.6±1.1 | Turkey | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 76 | 39±9 | 30.1±4.5 | |||||||

| Eminler et al. 201421 | Control | 40 (18/22) | NA | NA | Turkey | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 6 |

| NAFLD | 40 (21/19) | NA | NA | |||||||

| Floreani et al. 200832 | Control | 137 (12/125) | 60.2±10.4 | NA | USA | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 4 |

| NASH | 30 (0/30) | 49.9±3.7 | 24.5±2.8 | |||||||

| Musso et al. 200528 | Control | 25 (23/2) | 38±2 | 25.2±0.6 | Italy | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NASH | 25 (23/2) | 37±2 | 25.3±0.2 | |||||||

| Jarrar et al. 200812 | Control | 38 (5/33) | 40±9.5 | 47.5±9.4 | USA | Case-control | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 6 |

| NAFLD | 45 (13/32) | NA | NA | |||||||

| SS | 19 (2/17) | 37±9.2 | 47.2±7.5 | |||||||

| NASH | 26 (11/15) | 43.9±11.4 | 47.5±8.3 | |||||||

| Jiang et al. 200934 | Control | 43 | 51.1±12.5 | 24.81±1.91 | China | Case-control | Ultrasound | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 43 | 52.6±10.8 | 25.75±1.91 | |||||||

| Jamali et al. 201631 | Control | 18 (13/5) | 30.44±10.11 | 29.28±3.89 | Iran | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 18 (13/5) | 34.5±8.85 | 31.58±3.94 | |||||||

| Krawczyk et al. 200933 | Control | 16 | NA | 22.6±2.5 | Poland | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 6 |

| NASH | 18 (16/2) | 42.55±21 | 26.6±4 | |||||||

| Musso et al. 201335 | Control | 51 (33/18) | 56±1 | 26±0.3 | Italy | Cross sectional | Ultrasound | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 161 (101/60) | 56±1 | 27.3±0.5 | |||||||

| Magalhaes et al. 201436 | Control | 36 | 37.9±1.3 | 36.7 (30.3–55.4) | Brazil | Cross sectional | Ultrasound | No | ELISA | 5 |

| NAFLD | 24 | 39.5±1.6 | 39.4 (30.3–63.2) | |||||||

| Musso et al. 201738 | Control | 75 (61/14) | 50±1 | 25.9±0.2 | Italy | Cross sectional | Ultrasound | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 230 (59/171) | 49±1 | 25.7±0.3 | |||||||

| Musso et al. 201225 | Control | 40 | 50±3 | 25.1±1.6 | USA | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| SS | 20 | 47±4 | 25.1±1.5 | |||||||

| NASH | 20 | 47±4 | 25.2±1.6 | |||||||

| Perseghin et al. 200639 | Control | 47 (38/9) | 36±8 | 26.8±3 | USA | Case-control | NA | No | ELISA | 6 |

| NAFLD | 28 (24/4) | 35±8 | 27.1±3.9 | |||||||

| Polyzos et al. 201627 | Control | 25 (5/20) | 53.6±1.8 | 30.5±0.8 | Greece | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| SS | 15 (5/10) | 53.9±2.6 | 31.9±1.3 | |||||||

| NASH | 14 (2/12) | 54.8±1.6 | 33.9±1.6 | |||||||

| D’Incao et al. 201729 | Control | 4 | 38.5±10.85 | 49±6.73 | Brazil | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 7 |

| SS | 9 | 39.08±9.63 | 53.19±9.44 | |||||||

| NASH | 12 | 49.45±6.71 | 47.53±6.33 | |||||||

| Jamali et al. 201623 | SS | 2 (2/0) | 27±2.82 | 28.09±7.77 | Iran | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 6 |

| NASH | 28 (17/11) | 35±8.47 | 29.92±3.79 | |||||||

| Sanal et al. 200917 | Control | 18 | 44±8 | NA | India | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 6 |

| NAFLD | 56 | 43±14 | NA | |||||||

| Senates et al. 20129 | Control | 66 (33/33) | 39±9 | 23±4 | Turkey | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 97 (55/42) | 41±10 | 31±6 | |||||||

| Shen et al. 201422 | Control | 43 (29/14) | 45±14 | 22±1.8 | China | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 58 (38/20) | NA | NA | |||||||

| Wong et al. 200616 | Control | 41 (17/24) | 42±10 | 24.1±6.8 | China | Case-control | Liver biopsy | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 80 (52/28) | 45±9 | 29±4.8 | |||||||

| Younossi et al. 201130 | SS | 39 (3/36) | 40.51±10.28 | NA | USA | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 7 |

| NASH | 40 (15/25) | 44.08±10.05 | NA | |||||||

| Zhu et al. 201637 | Control | 86 (57/29) | 52.98±13.07 | 22.86±2.94 | China | Case-control | Ultrasound | No | ELISA | 7 |

| NAFLD | 86 (57/29) | 53±13.24 | 26.16±3.33 | |||||||

| Younossi et al. 200824 | Control | 32 (13/19) | 39.3±9.8 | 47±9.1 | USA | Cross sectional | Liver biopsy | Yes | ELISA | 7 |

| SS | 15 (1/14) | 37.4±8.3 | 45.7±4.8 | |||||||

| NASH | 22 (9/13) | 42.5±10.4 | 48.2±8.7 |

Data are presented in numbers or mean±SD or medians and interquartile ranges. BMI, body mass index; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; NA, not available.

Comparison of the serum resistin levels in NAFLD patients and controls

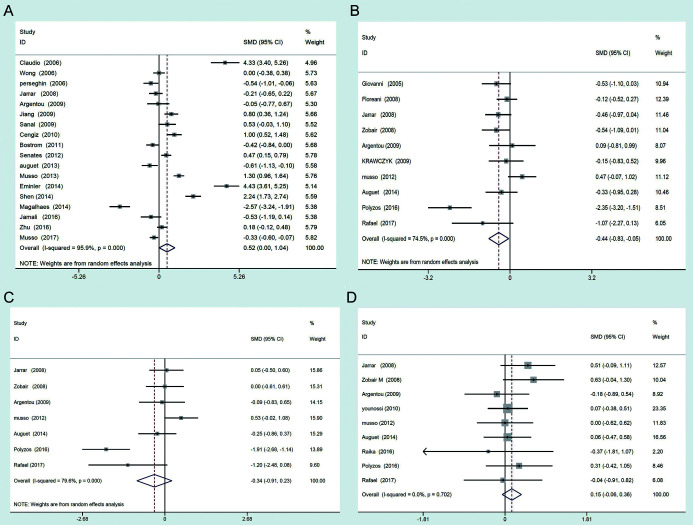

A total of 1,934 patients with NAFLD and 1,240 controls were included in this study. Only 18 of the included 28 studies investigated the serum resistin levels in NAFLD patients (NAFLD patients were not divided into the NAFL or NASH) and healthy controls. Random-effects model was used to conduct the meta-analysis and the results showed that patients with NAFLD had higher serum resistin levels than controls (SMD=0.522, 95% CI: 0.004–1.040, I2=95.9%) (Fig. 2A). Ten studies investigated the serum resistin levels in patients with NASH and healthy controls. Random-effects model was used to conduct the meta-analysis and the results showed that patients with NASH had lower serum resistin levels than the healthy controls (SMD=−0.44, 95% CI: −0.83–0.55, I2=74.5%) (Fig. 2B). Seven studies investigated the serum resistin levels in patients with NAFL and healthy controls. Random-effects model was used to conduct the meta-analysis and no significant difference of serum resistin levels was observed between patients with NAFL and healthy controls (SMD=−0.34, 95% CI: −0.91–0.23, I2=79.6%) (Fig. 2C). Nine studies investigated the serum resistin levels in patients with NAFL and NASH. Fixed-effects model was used to conduct the meta-analysis and the results showed that there was no significant difference of serum resistin levels between patients with NAFL and NASH (SMD=0.15, 95% CI: −0.06–0.36, I2=0.00%) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Forest plots of serum resistin levels between (A) NAFLD patients vs. controls, (B) NASH patients vs. controls, (C) NAFL patient vs. controls, (D) NAFL patients vs. NASH patients.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

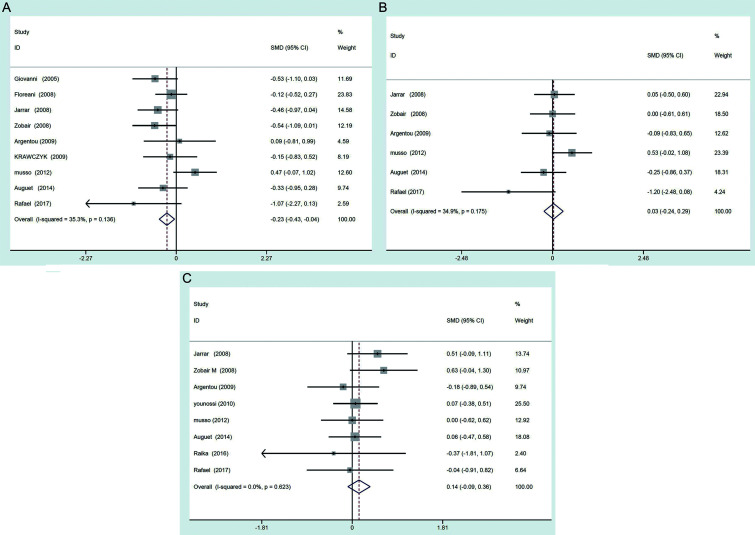

In consideration of significant heterogeneity existing between the NASH group vs. controls, NAFL group vs. controls, and NAFL group vs. NASH group, sensitivity analysis was carried out to explore the possible sources of heterogeneity in the included studies. Each study was evaluated by exclusion in turn, and then the summarized SMD of the remaining studies were calculated. Only when the study conducted by Polyzos et al.27 was removed, the heterogeneity was significantly reduced, which indicated that this study was the main source of heterogeneity. In order to investigate whether this study affected the results of meta-analysis, the meta-analysis were reperformed after removal of the study (Polyzos et al. 2016) with the fixed-effects model. The results showed that patients with NASH had lower serum resistin levels than controls (SMD=−0.23, 95% CI: −0.43–0.04) (Fig. 3A); there was no significant difference of serum resistin levels between patients with NAFL vs. controls (SMD=0.03, 95% CI: −0.24–0.29) (Fig. 3B), and between patients with NAFL vs. NASH patients (SMD=0.14, 95% CI: −0.09–0.36) (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that the heterogeneity did not affect the results of meta-analysis.

Fig. 3. Forest plots of serum resistin levels between (A) NASH patients vs. controls, (B) NAFL patient vs. controls, (C) NAFL patients vs. NASH patients after removed the study by Polyzos et al. (2016).

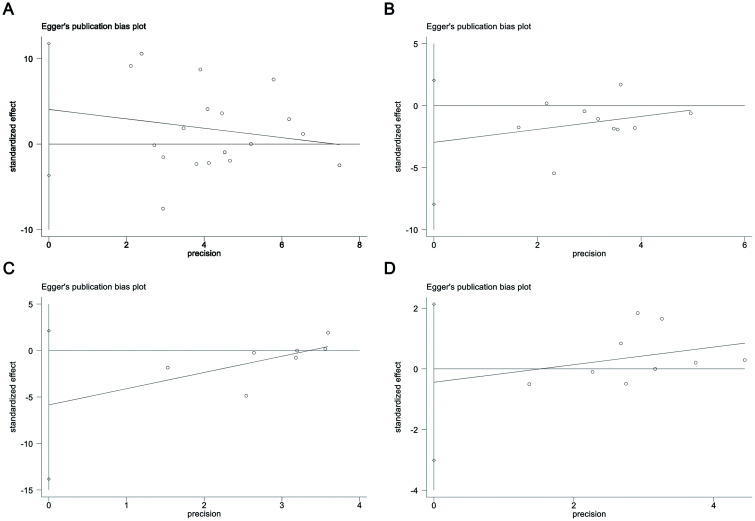

The same method was used to explore the source of heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of studies for NAFLD patients vs. controls, but no study was found to contribute to the heterogeneity. In addition, the subgroup analysis was conducted according to the diagnosis methods, ethnicity, mean age, types of study design, and mean body mass index, but all of them failed to be the obvious source of heterogeneity. Funnel plots were constructed using the Egger’s regression asymmetry test to investigate the possible publication bias in the NAFLD patients vs. controls, NASH patients vs. controls, NAFL patient vs. controls, and NAFL patients vs. NASH patients. As Figure 4 shows, no obvious publication bias was observed.

Fig. 4. Egger’s funnel plots for publication bias for (A) NAFLD patients vs. controls, (B) NASH patients vs. controls, (C) NAFL patient vs. controls, (D) NAFL patients vs. NASH patients.

Meta-regression and quality evaluation

To further explore the source of heterogeneity between NAFLD and control groups, the effect of potential confounders were evaluated by meta-regression analysis (based upon random-effects) when ≥10 comparisons were available. Diagnosis methods, ethnicity, mean age, types of study design, mean body mass index, biopsy on controls, and NOS scores were entered separately as covariates. As Table 2 shows, all of these factors failed to account for the heterogeneity between NAFLD and controls (Table 2). The GRADE approach was used to evaluate the quality of the evidence, and the results showed that the quality of results of serum resistin levels in NAFLD patients vs. controls was low, and moderate in NASH patients vs. controls, NAFL patient vs. controls, and NAFL patients vs. NASH patients, which suggested that further research is likely to have an important impact on the present results and may change the present results (please see the Supplementary Tables 1–5).

Table 2. Meta regression analysis of possible sources of heterogeneity in NAFLD vs. control group (18 studies).

| Effect size | Coefficient | Standard error | t | p>| t | | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis methods | 0.403 | 0.325 | −1.13 | 0.276 | 0.073–2.225 |

| Ethnicity | 0.175 | 0.223 | −1.58 | 0.133 | 0.175–1.287 |

| Types of study design | 1.527 | 1.318 | 0.49 | 0.631 | 0.245–9.513 |

| Mean age (30–40, 40–50, ≥50) | 0.814 | 0.346 | −0.48 | 0.635 | 0.331–2.003 |

| Mean BMI (>30) | 0.467 | 0.246 | −1.44 | 0.168 | 0.153–1.428 |

| Biopsy on controls | 0.367 | 0.393 | −0.94 | 0.363 | 0.038–3.552 |

| NOS score | 1.996 | 0.783 | 1.76 | 0.097 | 0.869–4.586 |

Discussion

Resistin is a significant pro-inflammation adipokine and the role of its serum levels in patients with NAFLD remain controversial. This study systematically analyzed the serum levels of resistin in patients with NAFLD, especially in those with NAFL and NASH. The results suggested that patients with NAFLD had higher serum resistin levels than healthy controls, but low serum resistin levels were observed in patients with NASH when compared to healthy controls. In addition, no significant difference of serum resistin levels was observed between patients with NAFL and healthy controls, and between patients with NAFL and NASH. A reasonable explanation may be that all the patients with NASH and NAFL were diagnosed by liver biopsy, and patients with NAFLD were diagnosed by liver biopsy or ultrasound. The difference of diagnostic methods may contribute to these outcomes.

Some previous studies reported that serum levels of resistin in patients with NAFLD were higher,15 lower,39 or of no significant difference40 compared to healthy controls, accompanied by the different diagnosis methods used for NAFLD. Zhu et al.37 investigated the levels of serum protein as the diagnostic biomarkers for NAFLD, and they found that serum resistin was significantly higher in patients with NAFLD than in healthy controls. However, Magalhaes et al.36 investigated the serum levels of resistin in obese NAFLD patients and controls, but they found that the serum levels of resistin were negatively associated with the risk of NAFLD; that is, the serum resistin levels were low in NAFLD patients compared to controls. Except for the above reports, other research investigations also provided findings that precluded making a definitive conclusion. In this meta-analysis, we analyzed all the available studies which investigated the serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD and controls, and we found that serum resistin levels were significant higher than in the healthy controls. Notably, all the patients with NAFLD were diagnosed by liver biopsy or ultrasound, and the NAFLD patients were not divided by NAFL and NASH stage. In consideration of the high heterogeneity in the meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis was conducted. Interestingly, when the study by Polyzos et al.27 (2016) was removed, the heterogeneity was markedly decreased, but the results of meta-analysis were unchanged. These results indicated that an individual study may contribute to the heterogeneity, but whether the results of meta-analysis were affected should be further investigated.

Resistin up-regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in monocytes, macrophages, and hepatic stellate cells via the NF-κB pathway.41 Serum resistin levels in patients with NASH and the association of serum resistin levels with the risk fibrosis remains inconsistent. Argentou et al.10 investigated the relationship of serum resistin levels with some individual histopathological parameters, global activity grade, and fibrosis stage in NASH patients, but no significant association was observed. However, Tsochatzis et al.42 reported the serum levels in chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C patients; they also found that low resistin levels were associated with moderate/severe fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B/C patients, which suggested that serum resistin levels were negatively related to the degree of fibrosis. In this meta-analysis, the serum resistin levels in patients with NASH were significantly lower than in healthy controls, which was consistent with the previous study by Tsochatzis et al.42 to some degree. The probable reason may be that patients with NASH possess different degrees of fibrosis, usually, and the serum resistin levels could be negatively associated with the fibrosis. In this study, however, all the patients with NASH had NAFLD-related NASH, and the cause of fibrosis in NASH patients was different from that of the chronic hepatitis B/C patients. Whether the relationship of serum resistin levels with fibrosis was affected by the cause of fibrosis remains unknown and further studies are needed to clarify it.

Our results suggested that patients with NAFLD had higher serum resistin levels than healthy controls, but low serum resistin levels were observed in the patients with NASH compared to healthy controls. This is an interesting finding because resistin levels seem to rise with the progression of NAFLD, from healthy to NAFL, but decline when NAFL progresses to NASH. The same phenomenon occurred in patients with type 2 diabetes. In 2020, Galla et al.43 reported that patients with prediabetes had higher levels of resistin than patients with type 2 diabetes and healthy controls, as found in their 20-year follow-up study. In addition, a large number of cohort studies and meta-analysis suggested that resistin is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.44 Acute coronary syndromes often occur in patients with high resistin levels, while chronic stable angina pectoris is more common in patients with low resistin levels.45 Given that pre-diabetes and coronary heart disease are a large part of the hidden population,43,46 patients with NAFLD are more likely to suffer from the type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease, which may have affected the results of this study. In addition, whether reduced resistin levels will reduce the risk of NAFL, type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease is unknown, and more research is needed in the future.

This meta-analysis has strengths and limitations that may have affected its conclusions. This is the first meta-analysis to systematically investigate the serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD. The serum resistin levels were evaluated in patients with NAFLD, including patients with NAFL and NASH. In addition, this work is based on 28 high-quality studies. The limitations, however, include that some NAFLD patients were diagnosed by ultrasound other than liver biopsy in the included studies. Second, higher heterogeneity may disturb the accuracy of the results. Third, the association of serum resistin levels with fibrosis was not investigated in detail in this study. Fourth, although every step of this meta-analysis was carried out in strict accordance with the requirements, this meta-analysis was not registered on relevant websites in advance.

Conclusions

In summary, this study systematically investigated the serum resistin levels in adult patients with NAFLD for the first time. The results suggest that patients with NAFLD have higher serum resistin levels than healthy controls, but patients with NASH have lower serum resistin levels than healthy controls. In addition, no significant differences of serum resistin levels were observed between the patients with NAFL and controls, nor the patients with NAFL and NASH. Although a little inconsistence between the results of this study and several previous studies existed, it remains reasonable to illustrate the variation of serum resistin levels in patients with NAFLD. In consideration of the present results, serum resistin possesses the potential to serve as a biomarker to predict the development risk of NAFLD, and the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity should be improved by excluding the interference of other factors. Further studies should be conducted to clarify the serum resistin levels in healthy controls and patients with NAFLD that is diagnosed by liver biopsy.

Supporting information

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- FIIZ

found in inflammatory zone

- NAFL

nonalcoholic fatty liver

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa scale

- SD

standard deviation

- SMD

standardized mean difference

Data sharing statement

All data are available upon request.

References

- 1.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheka AC, Adeyi O, Thompson J, Hameed B, Crawford PA, Ikramuddin S. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A review. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1175–1183. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong VW, Chan WK, Chitturi S, Chawla Y, Dan YY, Duseja A, et al. Asia-Pacific Working Party on Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease guidelines 2017-Part 1: Definition, risk factors and assessment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33(1):70–85. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonardo A, Byrne CD, Caldwell SH, Cortez-Pinto H, Targher G. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(4):1388–1389. doi: 10.1002/hep.28584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd A, Cain O, Chauhan A, Webb GJ. Medical liver biopsy: background, indications, procedure and histopathology. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;11(1):40–47. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2018-101139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Mantzoros CS. Adipokines in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65(8):1062–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colica C, Abenavoli L. Resistin Levels in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Pathogenesis. J Transl Int Med. 2018;6(1):52–53. doi: 10.2478/jtim-2018-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoelson SE, Herrero L, Naaz A. Obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2169–2180. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senateş E, Colak Y, Yeşil A, Coşkunpinar E, Sahin O, Kahraman OT, et al. Circulating resistin is elevated in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and is associated with steatosis, portal inflammation, insulin resistance and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis scores. Minerva Med. 2012;103(5):369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argentou M, Tiniakos DG, Karanikolas M, Melachrinou M, Makri MG, Kittas C, et al. Adipokine serum levels are related to liver histology in severely obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19(9):1313–1323. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koehler E, Swain J, Sanderson S, Krishnan A, Watt K, Charlton M. Growth hormone, dehydroepiandrosterone and adiponectin levels in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: an endocrine signature for advanced fibrosis in obese patients. Liver Int. 2012;32(2):279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarrar MH, Baranova A, Collantes R, Ranard B, Stepanova M, Bennett C, et al. Adipokines and cytokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(5):412–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick E, Dew TK, Quaglia A, Sherwood RA, Mitry RR, Dhawan A. Analysis of adipokine concentrations in paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(6):471–479. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Robertson J, Peterson J, Welch V, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta analyses. Available from: http://www3.med.unipmn.it/dispense_ebm/2009-2010/Corso%20Perfezionamento%20EBM_Faggiano/NOS_oxford.pdf.

- 15.Pagano C, Soardo G, Pilon C, Milocco C, Basan L, Milan G, et al. Increased serum resistin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is related to liver disease severity and not to insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(3):1081–1086. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong VW, Hui AY, Tsang SW, Chan JL, Tse AM, Chan KF, et al. Metabolic and adipokine profile of Chinese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(9):1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanal MG, Sarin SK. Serum adipokine profile in Indian men with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Serum adiponectin is paradoxically decreased in lean vs. obese patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2009;3(4):198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2009.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cengiz C, Ardicoglu Y, Bulut S, Boyacioglu S. Serum retinol-binding protein 4 in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: does it have a significant impact on pathogenesis? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22(7):813–819. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32833283cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boström EA, Ekstedt M, Kechagias S, Sjöwall C, Bokarewa MI, Almer S. Resistin is associated with breach of tolerance and anti-nuclear antibodies in patients with hepatobiliary inflammation. Scand J Immunol. 2011;74(5):463–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auguet T, Terra X, Porras JA, Orellana-Gavaldà JM, Martinez S, Aguilar C, et al. Plasma visfatin levels and gene expression in morbidly obese women with associated fatty liver disease. Clin Biochem. 2013;46(3):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eminler AT, Aygun C, Konduk T, Kocaman O, Senturk O, Celebi A, et al. The relationship between resistin and ghrelin levels with fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19(11):1058–1061. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen C, Zhao CY, Wang W, Wang YD, Sun H, Cao W, et al. The relationship between hepatic resistin overexpression and inflammation in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamali R, Hatami N, Kosari F. The correlation between serum adipokines and liver cell damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepat Mon. 2016;16(5):e37412. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.37412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Younossi ZM, Jarrar M, Nugent C, Randhawa M, Afendy M, Stepanova M, et al. A novel diagnostic biomarker panel for obesity-related nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) Obes Surg. 2008;18(11):1430–1437. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9506-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musso G, Cassader M, De Michieli F, Rosina F, Orlandi F, Gambino R. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus steatosis: adipose tissue insulin resistance and dysfunctional response to fat ingestion predict liver injury and altered glucose and lipoprotein metabolism. Hepatology. 2012;56(3):933–942. doi: 10.1002/hep.25739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auguet T, Berlanga A, Guiu-Jurado E, Terra X, Martinez S, Aguilar C, et al. Endocannabinoid receptors gene expression in morbidly obese women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:502542. doi: 10.1155/2014/502542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Polymerou V, Papadimitriou KG, Zavos C, Katsinelos P. Vaspin, resistin, retinol-binding protein-4, interleukin-1α and interleukin-6 in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2016;15(5):705–714. doi: 10.5604/16652681.1212429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Musso G, Gambino R, Durazzo M, Biroli G, Carello M, Fagà E, et al. Adipokines in NASH: postprandial lipid metabolism as a link between adiponectin and liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1175–1183. doi: 10.1002/hep.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D’Incao RB, Tovo CV, Mattevi VS, Borges DO, Ulbrich JM, Coral GP, et al. Adipokine Levels Versus Hepatic Histopathology in Bariatric Surgery Patients. Obes Surg. 2017;27(8):2151–2158. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2627-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Younossi ZM, Page S, Rafiq N, Birerdinc A, Stepanova M, Hossain N, et al. A biomarker panel for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and NASH-related fibrosis. Obes Surg. 2011;21(4):431–439. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamali R, Razavizade M, Arj A, Aarabi MH. Serum adipokines might predict liver histology findings in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(21):5096–5103. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i21.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Floreani A, Variola A, Niro G, Premoli A, Baldo V, Gambino R, et al. Plasma adiponectin levels in primary biliary cirrhosis: a novel perspective for link between hypercholesterolemia and protection against atherosclerosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(8):1959–1965. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krawczyk K, Szczesniak P, Kumor A, Jasinska A, Omulecka A, Pietruczuk M, et al. Adipohormones as prognostric markers in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60(Suppl 3):71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang LL, Li L, Hong XF, Li YM, Zhang BL. Patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease display increased serum resistin levels and decreased adiponectin levels. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21(6):662–666. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328317f4b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Musso G, Bo S, Cassader M, De Michieli F, Gambino R. Impact of sterol regulatory element-binding factor-1c polymorphism on incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and on the severity of liver disease and of glucose and lipid dysmetabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):895–906. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.063792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magalhães GC, Feitoza FM, Moreira SB, Carmo AV, Souto FJ, Reis SR, et al. Hypoadiponectinaemia in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease obese women is associated with infrequent intake of dietary sucrose and fatty foods. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27(Suppl 2):301–312. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu JZ, Zhu HT, Dai YN, Li CX, Fang ZY, Zhao DJ, et al. Serum periostin is a potential biomarker for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a case-control study. Endocrine. 2016;51(1):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0735-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musso G, Cassader M, De Michieli F, Paschetta E, Pinach S, Saba F, et al. MERTK rs4374383 variant predicts incident nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes: role of mononuclear cell activation and adipokine response to dietary fat. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(9):1747–1758. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perseghin G, Lattuada G, De Cobelli F, Ntali G, Esposito A, Burska A, et al. Serum resistin and hepatic fat content in nondiabetic individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(12):5122–5125. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho YK, Lee WY, Oh SY, Park JH, Kim HJ, Park DI, et al. Factors affecting the serum levels of adipokines in Korean male patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(77):1512–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landecho MF, Tuero C, Valentí V, Bilbao I, de la Higuera M, Frühbeck G. Relevance of leptin and other adipokines in obesity-associated cardiovascular risk. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2664. doi: 10.3390/nu11112664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsochatzis E, Papatheodoridis GV, Hadziyannis E, Georgiou A, Kafiri G, Tiniakos DG, et al. Serum adipokine levels in chronic liver diseases: association of resistin levels with fibrosis severity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(9):1128–1136. doi: 10.1080/00365520802085387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galla OJ, Ylitalo A, Kiviniemi A, Huikuri H, Kesäniemi YA, Ukkola O. Peptide hormones and risk for future cardiovascular events among prediabetics: a 20-year follow-up in the OPERA study. Ann Med. 2020;52(3-4):85–93. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2020.1741673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang JZ, Gao Y, Zheng YY, Liu F, Yang YN, Li XM, et al. Increased serum resistin level is associated with coronary heart disease. Oncotarget. 2017;8(30):50148–50154. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joksic J, Sopic M, Spasojevic-Kalimanovska V, Kalimanovska-Ostric D, Andjelkovic K, Jelic-Ivanovic Z. Circulating resistin protein and mRNA concentrations and clinical severity of coronary artery disease. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2015;25(2):242–251. doi: 10.11613/BM.2015.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou L, Li JY, He PP, Yu XH, Tang CK. Resistin: Potential biomarker and therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;512:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.