Abstract

Background:

The National Institute on Aging (NIA), in conjunction with the Department of Health and Human Services as part of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA), convened a 2020 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and their Caregivers. This review article addresses research participation by persons living with dementia (PLWD) and their care partners in two different ways: as research participants with input on outcomes studied, and as engaged research partners.

Results:

This article summarizes each of the topics presented at this Summit session, followed by reflection from the session panelists. Lee Jennings examined collection of outcomes directly from PLWD and the potential for individualized outcomes to enhance measurement in intervention trials. Ron Petersen discussed the impact of nomenclature on research and clinical care, and how and why investigators should be mindful of the connection between dementia nomenclature and the conduct of dementia research. Tabassum Majid examined strategies for engagement in research, including specific examples of involving persons living with dementia and their care partners (including staff in assisted living and skilled nursing facilities), and the potential for this research engagement to improve our understanding of interventions in dementia.

Conclusions:

Research participation by PLWD and their care partners is evolving. This review summarizes three areas of opportunity and steps for researchers to work with PLWD and their care partners to design and conduct research that enhances knowledge based on what we learn from PLWD and their care partners, and creates knowledge with them.

Keywords: goal attainment, dementia nomenclature, research engagement

Introduction

Persons living with dementia (PLWD) and their care partners can - and do - participate in research. The focus of one session of the 2020 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers was devoted to considering two different forms of research participation: as research participants, and as engaged research partners. Three presentations were delivered at this session. The first presentation, by Lee Jennings, examined collection of outcome domains directly from PLWD and the potential for individualized outcomes to enhance measurement in intervention trials. In the second presentation Ron Petersen discussed the impact of nomenclature on research and clinical care, and how and why investigators should be mindful of the connection between dementia nomenclature and the conduct of dementia research. The third presentation, by Tabassum Majid, examined strategies for engagement in research, including specific examples of involving persons living with dementia and their care partners (including staff in assisted living and skilled nursing facilities), and the potential for this research engagement to improve our understanding of interventions in dementia.

This article summarizes each of the topics presented at the Summit, followed by reflection from the session panelists, Andrea Gilmore-Bykovskyi, a clinician/researcher, and Lonnie Schicker, a PLWD, on challenges and opportunities for PLWD engagement with research. The common threads are communication, enhancing knowledge based on what we learn from PLWD and their care partners, and creating knowledge with them.

Reporters, Data Sources, and Outcomes in Dementia Research

Person-defined dementia care outcomes may be preferable to disease-based outcomes because they can account for multiple co-occurring conditions and capture overall quality of life, including broader social, emotional, and functional domains of health (see Figure 1).1,2 Person-defined outcomes also provide the opportunity to align clinical interventions toward meeting health goals that are most important to an individual. This is particularly relevant for PLWD as they often have multiple chronic conditions and face treatment decisions that may require trade-offs or care that may be burdensome, especially as dementia progresses.

Figure 1.

What Matters Most? Findings from Focus Groups with Persons with Dementia and their Care Partners

Data are from: Jennings, L. A., Palimaru, A., Corona, M. G., et al. (2017). Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 26(3), 685–693.

Several opportunities already exist to operationalize these personalized outcomes in research. Goal attainment scaling is one approach to person-defined outcome measurement that has been used in dementia care research.3–9 Using a 5-category scale, an individual’s goal attainment can be quantified according to whether the PLWD or care partner met, exceeded, or failed to meet expected goals over a specified time-period. In this way, goals are individualized but measurement of the outcome (i.e., goal attainment) is standardized across the research cohort.

Validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have also been included in dementia care research as person-defined outcomes to assess PLWD quality of life,10 functional status,11 pain,12 neuropsychiatric symptoms,13 and care partner strain,14 among others. PROMS can be followed longitudinally and compared across studies; however, they may be too generic to capture some person-specific goals (e.g., attending a wedding) and often focus on deficits (i.e., loss of function) instead of strengths. There are few PROMS that address constructs of well-being in dementia, such as engagement in activities, resilience, humor and hope.15

Proxy-report is also a challenge for both goal attainment scaling and PROMs. Care partners may be asked to report an outcome for a PLWD, especially as dementia progresses and cognition worsens over time. A care partner may be able to accurately report observable outcomes, such as performance of activities of daily living or mobility, but may be less able to report upon the PLWD’s symptoms, such as pain or mood.16–18 Care partners may also change during the course of a study, creating challenges with the collection of longitudinal, repeated measures or discordance among proxy-reporters, especially as care partner relationship (e.g., spouse vs. child) can impact how outcomes are reported.19,20 Who reports the outcome measure impacts how research findings can be interpreted and generalized. If researchers avoid proxy-report, then studies may over-represent persons with early stage dementia who can still report for themselves. Alternatively, researchers who chose only proxy-reported outcomes may over-represent the care partner viewpoint and exclude from research those PLWD who do not have care partners. There is a need for the further development of methodologies to enhance the use of PLWD self-report,21 especially in moderate or advanced stage disease.

Person-defined outcomes (i.e., goal attainment scaling and PROMs) have both advantages and challenges (see Table). They ensure the inclusion of specific, meaningful, and diverse health goals as research outcomes for PLWD and their care partners. However, they take more time and training to elicit from research participants and present challenges related to proxy reporting, multiple reporters, and longitudinal measures.

Table 1.

Personalized or Individual-Specific Outcomes

| Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Specific, measurable health goals | Time constraints |

| Goals are personalized, meaningful to PLWD and care partners | Goal setting takes training and practice |

| Accommodates diverse preferences | Culture of disease-based care |

| Goals can be revised as disease progresses | Some goals may be unrealistic |

| Facilitates care planning | Goals of and for others (e.g., family, clinician) |

Novel approaches using technology and triangulation of data sources may provide some solutions to challenges with person-reported outcome measures in dementia research. For example, wearable devices22 may allow researchers to track mobility, gait or falls; video could be used to observe behavioral symptoms or sleep; smart phones or tablets could be used to collect data in real time in a home setting.23 These sources of data could be combined with PLWD and care-partner reported outcomes to help researchers further understand the impact of an intervention. Future work should develop methods for combining and weighting different sources of data and addressing multiple reporters and reporter discordance.

Ongoing research to further develop person-defined outcomes and inclusion of PLWD and care partners as members of the research team are critical to ensure that dementia care interventions help PLWD and care partners achieve what matters most to them.

Nomenclature for dementia care and services

The topic of nomenclature pertaining to diseases of aging and cognitive function is critically important. In surveying the disciplines that constitute the field, it has become apparent that there is lack of uniformity with regard to the terms they use to define some of the common neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies, and vascular cognitive impairment-dementia.24 These terms have variable definitions even within their own disciplines.

The words that are used to describe underlying types and degrees of cognitive impairment, particularly in aging, can have an enormous impact on comprehension of the underlying disorder, as well as how it is approached from diagnostic and treatment perspectives. For example, the term “dementia” has been altered to be used as an adjective referring to a person as “demented” which is unacceptable to most. Recognizing that nomenclature has wide ranging consequences for ethics, health disparities, perspectives of PLWD and/or care partners, and etiologies of the diseases, the Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services the United States National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease charged a group of individuals to address the issue of nomenclature across the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Alzheimer’s disease-related disorders (ADRD) spectra. Since this topic impacts scientists, clinicians, and persons living with the diseases, a multidisciplinary group was assembled as the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative.25,26

Consequently, the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative workgroup that has been charged with dealing with the topic of nomenclature has convened three subcommittees to deal with nomenclature from the following perspectives: 1) science/research 2) clinical practice and 3) public stakeholders. The organization of these subcommittees recognizes the imperative for the scientific community to use a sufficiently precise and agreed upon set of terminology to describe the fundamental underpinnings of the diseases. The clinicians charged with the task of translating the scientific nomenclature to patients and family members must keep the precision of the scientific terminology intact but make it comprehensible to lay persons.

The nomenclature of dementia is highly relevant to a variety of public stakeholders, including not only persons living with the disorders, but a variety of other groups and organizations including governmental agencies, advocacy groups, research participants and underrepresented groups. Governmental agencies must use consistent terminology when coordinating research directions at the National Institutes of Health as well as services and payments through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and educational activities (through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Advocacy organizations rely on nomenclature to translate information about the disorders to their constituents, on the one hand, and in communicating with legislative bodies that have an influence on funding for research and services. Nomenclature affects potential research participants seeking to comprehend the nature of a study and determining the appropriateness for themselves or their loved ones. Participation in research studies requires clear terminology to support the understanding of the diseases involved and the appropriate implications of the research studies for the participants, including accessibility and participation in clinical research studies by racial and ethnic minorities and other underrepresented groups.

Alzheimer’s disease is an excellent example of the evolving terminology and how it has been confusing for scientists, clinicians and public stakeholders. For many decades, Alzheimer’s disease was considered a clinical-pathological entity.27 By this, it was meant that the person fit a clinical profile of memory impairment and increasing challenges with cognitive function resulting in impairment in daily function. That constituted dementia, and subsequently, a rule-out exercise was undertaken by the clinician to see if there was another obvious cause of the cognitive impairment. If none was found, the person was labeled as having “probable Alzheimer’s disease.” The term “definite Alzheimer’s disease” could not be used until the person died, had an autopsy and neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles were revealed. However, with the advent of biomarkers, such as amyloid and tau PET imaging, these pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease can be identified in life. As such, since 2011, advisory committees have been convened by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association to try to incorporate the use of biomarkers with the clinical syndromes to refine the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in life, but the diagnosis still constituted a clinical-pathological entity. More recently, however, there has been a proposal by another committee convened by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association to propose that Alzheimer’s Disease be defined on its biological basis (i.e., the presence of amyloid and tau28). While this may be an advance for the development of therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease, it does present a challenge to conveying the change in use of the term “Alzheimer’s disease” to public stakeholders, who perceive it based on symptoms. This is a salient example of how dementia nomenclature is evolving and can be quite confusing. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Defining Alzheimer’s Disease

The Dementia Nomenclature Initiative workgroup to address these issues has been meeting over the past year. A framework has been proposed to address the issues of nomenclature from a variety of different perspectives to bring harmony to the overall exercise. At present, it is being proposed that the workgroup advance the notion of the separation of the clinical syndrome from the underlying pathophysiology of the degenerative diseases. With the evolution of the term “Alzheimer’s disease,” it will be increasingly important for all of the proponents to appreciate the difference between the clinical, syndromic presentation of an individual with cognitive impairment as opposed to the underlying pathophysiologic cause of the disease. This recognition of the separation of the definition of these disorders is expected to lead to a better understanding of the underlying issues.

The workgroup will present recommendations for consideration at the 2022 Summit on Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders. Research recommendations regarding the clarification of the terms and the approaches proposed will be presented to the Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services.

Engagement of persons living with dementia and care partners as research partners

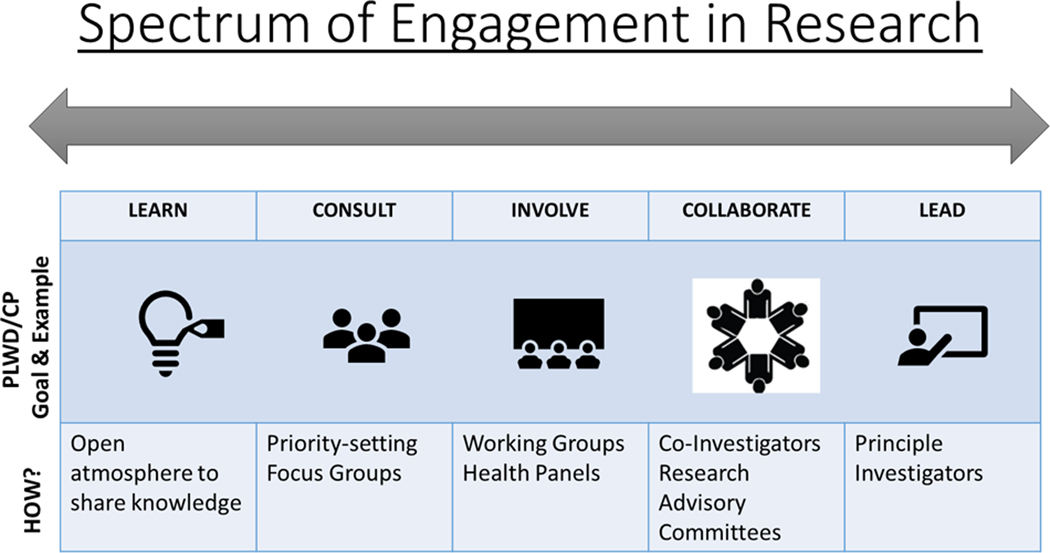

Individuals living with dementia and their caregivers can be engaged as partners in designing and conducting research, as well as participating in research participants. Engagement can occur throughout the lifecycle of a study on a spectrum,29 from learning/informing partners about their role to empowering or leading as equal members of the research team (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Spectrum of Engagement in Research, adapted from Vandall-Walker, et al. for persons living with dementia (PLWD) and care partners (CP).

Several recent studies offer strategies for involving PLWD and their care partners as engaged research partners, and highlight gaps in knowledge about engaged research. For example, one set of studies involving care partners, individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and providers of aging services used a research engagement approach30 to examine care management priorities in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. The research team presented care management concepts from the research literature to an advisory panel of care partners and persons living with MCI. Engaging stakeholders during the qualitative framework stage yielded new care management concepts that had not previously been defined,31 overcoming limitations in the existing literature and enhancing conceptual coverage of the work.

Due to the progressive nature of dementia, engaging individuals in the later stages of disease presents challenges. In a “meaningful music” study conducted in a long-term care community setting, PLWD care partners and direct care staff contributed as engaged partners in adaptation of study design, methods, and implementation.32 The study question was inspired by an operational challenge from direct care staff: what type of music was most person-centered for PLWD. As a result of this engagement, staff and families co-designed the time and frequency of the intervention that suited the daily activity cycle of the PLWD and enabled privacy and 1–1 interaction within the community. Care partners, PLWDs, and staff also were engaged in outcome selection and study design. Due to both the desire for appropriate blinding of the personally meaningful song and the control song intervention, study design was adapted from a double blind, two arm study, to a single blind, cohort-based study to maintain scientific rigor and balance stakeholder engagement. Engagement with care partners throughout the process resulted in meaningful data collection of music preference, history, and observed emotions before, during, and after the intervention. Notably, IRB consent procedures were also adapted to include informed consent and assent with PLWD in moderate to severe stages prior to any intervention taking place. Results from the pilot study included more expressions of pleasure, visual engagement with surroundings, and singing during and after the personally meaningful music intervention.32

Engaging stakeholders in the music study led to improvement in care practices within the community and disseminated to providers and researchers in other long-term care settings. Playlists and songs were shared with recreation and engagement staff to implement into resident daily routines, including small group activities and one-on-one engagement for every resident in the community, not just study participants. Efforts to engage and create a new “activated community” can be foundational for future research studies in a variety of care settings and throughout AD/ADRD progression.

These case examples illustrate opportunities to engage PLWD, care partners, and health care providers as partners in research across study lifecycles and disease stage. Opportunities to engage stakeholders early may enhance findings from the literature by identifying meaningful priorities and outcomes that are most meaningful to persons living with dementia and their care partners. Finally, engagement during study design provides unique opportunities to close the translational gap between results and implementation into a variety of care settings.

The two panelists for the session provided the following reflections on the issues raised by the findings from the presentation.

Measurement and Inclusion

Expanding the development of outcome measures important to PLWD remains an elusive target despite ongoing prioritization of this goal by PLWD, care partners, and researchers alike. Traditional measures used to capture the experiences of people living with dementia and their care partners largely focus on the extent, or alleviation of deficits. Commonly used measures frequently overlook domains relevant to the care and caregiving, such as existing strengths and abilities, and positive psychosocial and emotional dimensions of life and social connectedness.33 Exclusive reliance on deficit-oriented measures unnecessarily circumscribes areas of investigation and interventional targets for care and caregiving to aspects of the disease process associated with loss and impairment, and in doing so constrains attention to the intrinsic personhood of people living with dementia. Consequentially, important and potentially more sensitive endpoints may be omitted, and compensatory and supportive approaches may be designed without an understanding of the fund of facilitative strengths and abilities that could be leveraged to extend their positive influence.

The limited progress in development of positive and non-deficit oriented measures may reflect limited inclusion of people living with dementia and care partners throughout the research process. Indeed, broader inclusion of non-deficit-oriented measures may better capture nuanced facets of quality of life and wellbeing that may be of greater significance to PLWD than other outcomes. Clarifying the relative meaningfulness, optimal measurement strategies, and breadth of potential implications of expanded measurement will benefit from engaged research approaches that prioritize partnerships with PLWD and their care partners to not only obtain their input but enable their perspective and prioritizes to guide actions and inquiry. As of yet PLWD have rarely been afforded the opportunity to be directly involved in research regarding their needs, care, and priorities despite being the intended beneficiary of this knowledge.34

While studies with robust inclusion and engagement of PLWD and care partners remain limited, several successful efforts have broadened our understanding of their perspectives surrounding measurement. These studies have found that PLWD desire to engage in research efforts aimed at improving their well-being, confidence, health, social participation and human rights.35 A large systematic review and meta-synthesis integrating perspectives of 345 people living with dementia identified five common factors that influenced quality of life: connectedness and disconnectedness, relationships, agency, wellness perspective, and sense of place.36 Constructs of happiness and sadness were also identified as meaningful indicators of a good or poor quality of life. Recommendations provided by people living with dementia underscore the need for new outcomes that reflect positive constructs, which some researchers have suggested can be addressed through concepts in the field of positive psychology.37 Early stage validation of measures such as the Positive Psychology Outcome Measure and Engagement and Independence in Dementia Questionnaire have demonstrated acceptable preliminary psychometric properties.38 Collectively, these efforts lend compelling support for broader inclusion of people living with dementia and their care partners in the development and validation of broader outcome measures, as well as the importance of prioritizing this work. The involvement of people living with dementia and care partners can encompass various degrees and types of engagement, and collaborative efforts between researchers, advocacy organizations, and people living with dementia offer new guidance for supporting the engagement of people living with dementia that can inform these efforts.39

Collectively, the work presented here provides tangible paths forward to remedy under-inclusion of PLWD in research in tandem with development of expanded measures. The Dementia Nomenclature Initiative, whose membership includes PLWD and care partners represents an engaged approach toward addressing the myriad rhetorical challenges that impede robust dialogue, de-stigmatization, and understanding. Through committed actions to strengthen inclusion of PLWD and their care partners in research, the proposed roadmap for navigating the spectrum of engagement can be harnessed to establish PROMs, which will ultimately benefit from the engaged contributions of PLWD and their care partners.

From The Perspective Of Someone Living With Dementia

As someone living with dementia, I have the following views on the topics examined here. First, regarding nomenclature, distinctions need to be clear between early, middle, and late stages, and between different types of dementia. Clarifying that not everything is Alzheimer’s would be helpful. Many terms still used by others reinforce rather than reduce stigma. Clarifying the difference between younger onset and “early onset” dementia would be helpful for those living with dementia as well. Nomenclature should support communication, between doctors, and between patients and care partners and doctors.

Regarding research participation, include us – we have valuable insights and experience. When inviting participation, researchers should clearly communicate whether the invitation is to be a research participant – filling out questionnaires for example – or to be a research partner – helping to define the study questions for example. Am I a person that you are studying? Or am I person advising as a person with dementia? Miscommunication can be hurtful for people living with dementia. Researchers also need to explain their expectations, so that the individual can determine if she is or is capable of performing what is needed by the researcher.

Conclusion

The increasing emphasis on person-centeredness in clinical care and research adds energy to stakeholder engagement across research areas. Linked to the growing funding for and attention to engagement, the role of the PLWD in research is evolving in several directions.

First, the primacy of individually-identified goals is reflected in advances in goal attainment scaling as a method for identifying and measuring goals, and incorporating the results in clinical care. This method overcomes some of the challenges of reporting from individuals with cognitive impairment while preserving the centrality of patient-based goals.

Second, the language used to identify individuals – to themselves, to their families, but also in research and clinical care – is evolving. A new initiative to address the limitations of current dementia terminology reflects the centrality of lived experience by actively involving PLWD, their care partners, and their advocates along with clinicians and researchers in the work.

Third, there is an expanding literature detailing research and intervention studies in which PLWD and care partners are meaningfully engaged. The overview and examples confirm challenges with research engagement for those with cognitive impairment, but point to the feasibility as well as the value for outcomes selection.

At the heart of centering patients is inclusion, with the needs for communication that inclusion requires. Hearing directly from PLWD about their goals and their challenges is a first step for this work, represented here in multiple ways. This work points to the feasibility of direct communication with persons living with dementia and their caregivers to inform and enhance study outcomes and study design. Goals collected directly from PLWD can be useful as study outcomes and PLWD as engaged research partners can enhance study design and relevance of outcomes. Listening to and working with PLWD can enhance the quality, relevance, and impact of dementia research.

Key Points.

PLWD goals can be useful study outcomes.

Nomenclature updates are underway to improve comparison across studies.

PLWD as engaged research partners can enhance study design and relevance of outcomes.

Why does this matter? Listening to and working with PLWD to understand their goals and challenges can enhance research impact.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge the input of Jennifer Wolff and David Reuben, Summit Co-Chairs, on the content of the session and for input on this manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Angela Taylor, Lewy Body Dementia Association, to the Dementia Nomenclature Initiative work described here.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsor had no role in the conception, design, or preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosures & Funding Sources

Dr. Gilmore-Bykovskyi receives funding from the National Institute on Aging under Award Number K76AG060005 (PI Gilmore-Bykovskyi). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging.

Dr. Majid is an employee of PCORI. The views presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors, or its Methodology Committee.

Dr. Jennings reports no funding for this manuscript.

Dr. Frank reports no funding for this manuscript.

Dr. Petersen reports no funding for this manuscript.

Dr. Karlawish receives funding from the National Institute on Aging through the NIA IMPACT Collaboratory. This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54AG063546, which funds NIA Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer’s Disease and AD-Related Dementias Clinical Trials Collaboratory (NIA IMPACT Collaboratory). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose related to this work.

References

- 1.Tinetti ME, Costello DM, Naik AD, et al. Outcome Goals and Health Care Preferences of Older Adults With Multiple Chronic Conditions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e211271. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennings LA, Palimaru A, Corona MG, et al. Patient and caregiver goals for dementia care. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(3):685–693. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1471-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockwood K. Attainment of treatment goals by people with Alzheimer’s disease receiving galantamine: a randomized controlled trial. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174(8):1099–1105. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew J, Chong MS, Tay L, Fong Y-L. Outcomes of a multimodal cognitive and physical rehabilitation program for persons with mild dementia and their caregivers: a goal-oriented approach. Clin Interv Aging. Published online October 2015:1687–1694. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S93914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clare L, Kudlicka A, Oyebode JR, et al. Individual goal‐oriented cognitive rehabilitation to improve everyday functioning for people with early‐stage dementia: A multicentre randomised controlled trial (the GREAT trial). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(5):709–721. doi: 10.1002/gps.5076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knox K, Stanley J, Hendrix JA, et al. Development of a symptom menu to facilitate Goal Attainment Scaling in adults with Down syndrome-associated Alzheimer’s disease: a qualitative study to identify meaningful symptoms. J Patient-Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00278-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings LA, Ramirez KD, Hays RD, Wenger NS, Reuben DB. Personalized Goal Attainment in Dementia Care: Measuring What Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers Want: Personalized Goal Attainment in Dementia Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(11):2120–2127. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chester H, Beresford R, Clarkson P, et al. The Dementia Early Stage Cognitive Aids New Trial (DESCANT) intervention: A goal attainment scaling approach to promote self‐management. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. Published online December 15, 2020:gps.5479. doi: 10.1002/gps.5479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuben DB, Gill TM, Stevens A, et al. D‐CARE: The Dementia Care Study: Design of a Pragmatic Trial of the Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness of Health System–Based Versus Community‐Based Dementia Care Versus Usual Dementia Care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2492–2499. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowling A, Rowe G, Adams S, et al. Quality of life in dementia: a systematically conducted narrative review of dementia-specific measurement scales. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(1):13–31. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucks RS, Ashworth DL, Wilcock GK, Siegfried K. Assessment of Activities of Daily Living in Dementia: Development of the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale. Age Ageing. 1996;25(2):113–120. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.2.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herr K, Bjoro K, Decker S. Tools for Assessment of Pain in Nonverbal Older Adults with Dementia: A State-of-the-Science Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(2):170–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2308. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey K, Catty J, Langman A, et al. A review of instruments developed to measure outcomes for carers of people with mental health problems. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(3):164–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaugler JE, Bain LJ, Mitchell L, et al. Reconsidering frameworks of Alzheimer’s dementia when assessing psychosocial outcomes. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2019;5(1):388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller LM, Whitlatch CJ, Lee CS, Caserta MS. Care Values in Dementia: Patterns of Perception and Incongruence Among Family Care Dyads. The Gerontologist. 2019;59(3):509–518. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson S, Cooper C, Hoe J, Hamilton O, Stringer A, Livingston G. Proxy rated quality of life of care home residents with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(4):569–581. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216002167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Barnes DE, Newcomer RJ, Yaffe K. Caregiver Characteristics Are Associated with Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia: CAREGIVER CHARACTERISTICS AND DEMENTIA BEHAVIORS. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):796–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Römhild J, Fleischer S, Meyer G, et al. RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. Inter-rater agreement of the Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) self-rating and proxy rating scale: secondary analysis of RightTimePlaceCare data. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0959-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grill JD, Raman R, Ernstrom K, Aisen P, Karlawish J. Effect of study partner on the conduct of Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Neurology. 2013;80(3):282–288. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827debfe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank L, Lenderking WR, Howard K, Cantillon M. Patient self-report for evaluating mild cognitive impairment and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2011;3(6):35. doi: 10.1186/alzrt97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpe J, Forchhammer BH, Maier AM. Adapting Mobile and Wearable Technology to Provide Support and Monitoring in Rehabilitation for Dementia: Feasibility Case Series. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(4):e12346. doi: 10.2196/12346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rockwood K, Sanon Aigbogun M, Stanley J, et al. The Symptoms Targeted for Monitoring in a Web-Based Tracking Tool by Caregivers of People With Dementia and Agitation: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e13360. doi: 10.2196/13360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Jack CR. A brief history of “Alzheimer disease”: Multiple meanings separated by a common name. Neurology. 2019;92(22):1053–1059. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor A. Dementia Nomenclature Initiative (DeNomI). Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation. https://www.alzdiscovery.org/research-and-grants/portfolio-details/21399932 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petersen RC, Taylor A. Nomenclature. Presented at the: ADVISORY COUNCIL ON ALZHEIMER’S RESEARCH, CARE, AND SERVICES; January2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petersen RC. How early can we diagnose Alzheimer disease (and is it sufficient)?: The 2017 Wartenberg lecture. Neurology. 2018;91(9):395–402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandall-Walker V. Patient researcher engagement in health research: Competencies, strengths, readiness tools, and suggested course content. Presented at the: 2016; Edmonton, AB: Athabasca University and Alberta Innovates. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullins CD, Abdulhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous Patient Engagement in Comparative Effectiveness Research. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1587–1588. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Majid T. Identifying Caregiver Reported Outcomes for Comparative Effectiveness Research of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD). Presented at the: International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology Mid-year Meeting; April2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arcadia S. The Effects of Personally Meaningful Music on Mood and Behavior in Individuals with Dementia: A Pilot Study. Presented at the: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference; July2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke C, Woods B, Moniz-Cook E, et al. Measuring the well-being of people with dementia: a conceptual scoping review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18(1):249–263. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01440-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.. Frank L, Shubeck E, Schicker M, et al. Contributions of persons living with dementia to scientific research meetings. Results from the National Research Summit on Care, Services and Supports for Persons with Dementia and their Caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2020. April;28(4):421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.10.014. Epub 2019 Oct 28. PMID: 31784409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Øksnebjerg L, Diaz-Ponce A, Gove D, et al. Towards capturing meaningful outcomes for people with dementia in psychosocial intervention research: A pan-European consultation. Health Expect. 2018;21(6):1056–1065. doi: 10.1111/hex.12799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Rourke HM, Duggleby W, Fraser KD, Jerke L. Factors that Affect Quality of Life from the Perspective of People with Dementia: A Metasynthesis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):24–38. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stansfeld J, Stoner CR, Wenborn J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E, Orrell M. Positive psychology outcome measures for family caregivers of people living with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(8):1281–1296. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217000655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stoner CR, Orrell M, Long M, Csipke E, Spector A. The development and preliminary psychometric properties of two positive psychology outcome measures for people with dementia: the PPOM and the EID-Q. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):72–83. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0468-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gove D, Diaz-Ponce A, Georges J, et al. Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):723–729. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1317334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]