Abstract

The mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) has recently been identified as a key RIP3 (receptor interacting protein 3) downstream component of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-induced necroptosis. MLKL is phosphorylated by RIP3 and is recruited to the necrosome through its interaction with RIP3. However, it is still unknown how MLKL mediates TNF-induced necroptosis. Here, we report that MLKL forms a homotrimer through its amino-terminal coiled-coil domain and locates to the cell plasma membrane during TNF-induced necroptosis. By generating different MLKL mutants, we demonstrated that the plasma membrane localization of trimerized MLKL is critical for mediating necroptosis. Importantly, we found that the membrane localization of MLKL is essential for Ca2+ influx, which is an early event of TNF-induced necroptosis. Furthermore, we identified that TRPM7 (transient receptor potential melastatin related 7) is a MLKL downstream target for the mediation of Ca2+ influx and TNF-induced necroptosis. Hence, our study reveals a crucial mechanism of MLKL-mediated TNF-induced necroptosis.

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) plays a critical role in diverse cellular events including apoptosis and necroptosis1,2. TNF is also a major mediator of both inflammation and immunity and is involved in many pathological conditions and autoimmune diseases3. The molecular mechanisms of TNF signalling have been significantly worked out. For instance, it is known that TNF triggers the formation of a TNFR1 signalling complex by recruiting several effectors such as TRADD, RIP1 and TRAF2 to mediate different signalling pathways. Importantly, under certain conditions, this TNFR1 signalling complex (complex I) dissociates from the receptor and recruits other proteins to form different secondary complexes for apoptosis and necroptosis4-6. Necroptosis needs the presence of RIP3 (receptor interacting protein 3) and MLKL (mixed lineage kinase-domain like) in the necrosome7-11. Other proteins including CYLD and SIRT2 are also suggested to play a role in the formation of the necrosome12,13. Apoptosis is primarily initiated through the recruitment of the death domain protein FADD (Fas-associated death domain protein) to form complex II. FADD recruits and activates the initiator cysteine proteases caspases 8 and 10, which drive apoptosis2,14. Importantly, there is also cross-talk between these two pathways15-17.

Although the mechanism of TNF-induced apoptosis is well elucidated, the signalling events that lead to TNF-initiated necroptosis are still largely unknown. Caspase-independent necroptosis has been proposed to involve the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from mitochondria18,19. More recently, RIP3 has been found to be essential for recruiting MLKL and the mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 during TNF-induced necroptosis10,11,20. Although it has been suggested that PGAM5 is essential for mitochondrial fragmentation during necroptosis, the mechanism of MLKL function in TNF-induced necroptosis is still unknown.

Here we show that MLKL forms homotrimers and locates to the cell plasma membrane during TNF-induced necroptosis. Importantly, we found that MLKL membrane localization is critical for Ca2+ influx. Furthermore, we identified TRPM7 as a MLKL downstream target to mediate Ca2+ influx and TNF-induced necroptosis. Our study reveals a key mechanism of MLKL-mediated necroptosis.

RESULTS

MLKL forms trimers on necroptosis induction

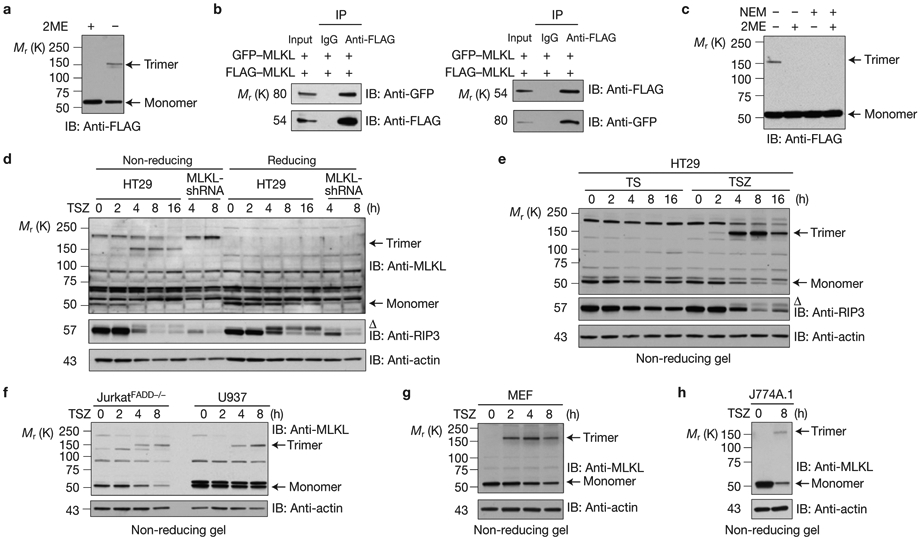

To explore how MLKL mediates TNF-induced necroptosis, we first investigated whether MLKL forms oligomers, because its N terminus contains two coiled-coil domains, predicted by the MultiCoil program21. Interestingly, these coiled-coil motifs are highly conserved among the MLKL orthologues in different vertebrate species (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the MultiCoil scores suggest that these two coiled-coil motifs of MLKL most likely form three-stranded coiled-coils (Supplementary Fig. 1b). To determine whether MLKL protein can oligomerize, we overexpressed MLKL in HEK293 cells and analysed MLKL protein expression by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing and non-reducing conditions. Interestingly, although MLKL protein was detected as a monomer at Mr 54K under reducing conditions as observed previously10,11, it was also spotted at about Mr 160K, roughly threefold of a MLKL monomer (Fig. 1a). When GFP–MLKL and FLAG–MLKL were co-expressed, GFP–MLKL was co-precipitated with FLAG–MLKL protein and vice versa (Fig. 1b). These results indicated that the MLKL protein indeed oligomerizes and most likely forms homotrimers when it is overexpressed in HEK293 cells. As reducing agents, such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (2ME), eliminated the trimeric form of MLKL, the trimers of MLKL protein are probably stabilized by disulphide bonds. When MLKL-transfected cells were lysed in the lysis buffer with N-ethylmaleimide, which blocks reactive sulphydryl groups, the trimeric band of MLKL disappeared even in the non-reducing condition, suggesting that the disulphide bonds of the trimerized MLKL proteins were formed by oxidation during cell lysis (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

MLKL forms homotrimeric protein on necrosis induction. (a) HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG–MLKL. The cell lysates were resolved on an SDS–PAGE gel with or without β-mercaptoethanol (2ME) and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. (b) HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP–MLKL and FLAG–MLKL as indicated. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated either with anti-FLAG antibody (left panel) or anti-GFP antibody (right panel) and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (c) HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG–MLKL, then lysed with or without 30 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block all reactive sulphydryl groups. The cell lysates were resolved with or without 2ME and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody. (d,e) Control-shRNA or MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells were treated with TSZ (TNF, Smac mimetic and the caspase inhibitor z-VAD-FMK) or TS (TNF and Smac mimetic) as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved either on reducing or non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (f–h) JurkatFADD−/−, U937 (f), MEF (g) and J774A.1 (h) cells were treated with TSZ at different time points as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Δ indicates phosphorylated RIP3. All western data are representative of two or three independent experiments. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

To examine whether the MLKL protein forms trimers in cells induced to undergo necroptosis, we treated HT29 cells with a combination of TNF, Smac mimetic, and the caspase inhibitor z-VAD-FMK (TSZ). MLKL proteins were detected as monomers at a relative molecular mass of 54,000 (Mr 54 K) under reducing conditions, whereas MLKL proteins were detected as trimers as early as 2 h after TSZ treatment under non-reducing conditions (Fig. 1d). In particular, most of the MLKL protein existed as trimers at 4 and 8 h following TSZ treatment (Fig. 1d). The HT29 cells stably transfected with a MLKL short hairpin RNA (shRNA) were used as a control for the specificity of the anti-MLKL antibody (Fig. 1d). Importantly, MLKL protein forms trimers in necrotic cells (TSZ treatment), and not in apoptotic cells (TS treatment; Fig. 1e). The observation of MLKL trimerization in necrotic cells seems to be a general phenomenon because MLKL protein also forms trimers in the necrotic JurkatFADD−/−, U937, mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) and mouse J774A.1 cells, all of which are sensitive to TSZ-induced necroptosis (Fig. 1f-h). Taken together, these results suggest that MLKL protein trimerizes during necroptosis.

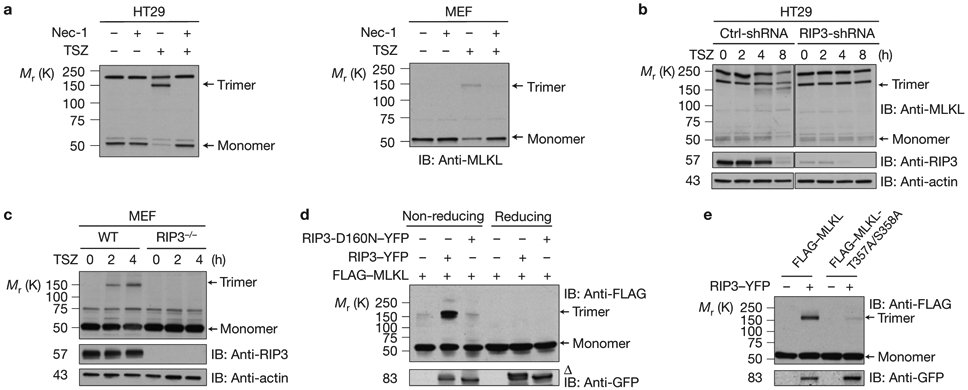

RIP3 kinase is critical for MLKL trimerization

As the upstream regulators of TNF-induced necroptosis, both RIP1 and RIP3 are required for the trimerization of MLKL because treating the HT29 and MEF cells with necrostatin-1, a RIP1 inhibitor22, or knocking down RIP3 in HT29 cells or the deletion of RIP3 in MEF cells prevented the trimerization of MLKL (Fig. 2a-c). As RIP3 phosphorylates MLKL (refs 10,11), we then examined whether RIP3 facilitates MLKL trimerization. When wild-type (WT) or the kinase-dead RIP3 was co-expressed with MLKL in HEK293 cells, the WT RIP3, but not the mutant RIP3-D160N, markedly increased the formation of MLKL trimers under non-reducing conditions (Fig. 2d). In addition, when the two main RIP3-phosphorylation sites of MLKL were mutated10, RIP3 was no longer able to significantly promote the trimerization of the mutant MLKL-T357A/S358A (Fig. 2e). These results suggest that the kinase activity of RIP3 is critical for promoting MLKL trimerization.

Figure 2.

RIP3 kinase activity is critical for MLKL trimerization (a) HT29 cells (left) or MEF cells (right) were pre-treated with or without necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) and then treated with TSZ for 4 h. The cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-MLKL antibody. (b) Control-shRNA or RIP3-shRNA HT29 cells were treated with TSZ as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-MLKL antibody. (c) WT or RIP3-deficient MEF cells were treated with TSZ and cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (d) HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG–MLKL, RIP3–YFP or RIP3-D160N–YFP as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved either on reducing or non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (e) HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG–MLKL or FLAG–MLKL-T357A/S358A with or without RIP3–YFP as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Δ indicates phosphorylated RIP3. All western data are representative of two or three independent experiments. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

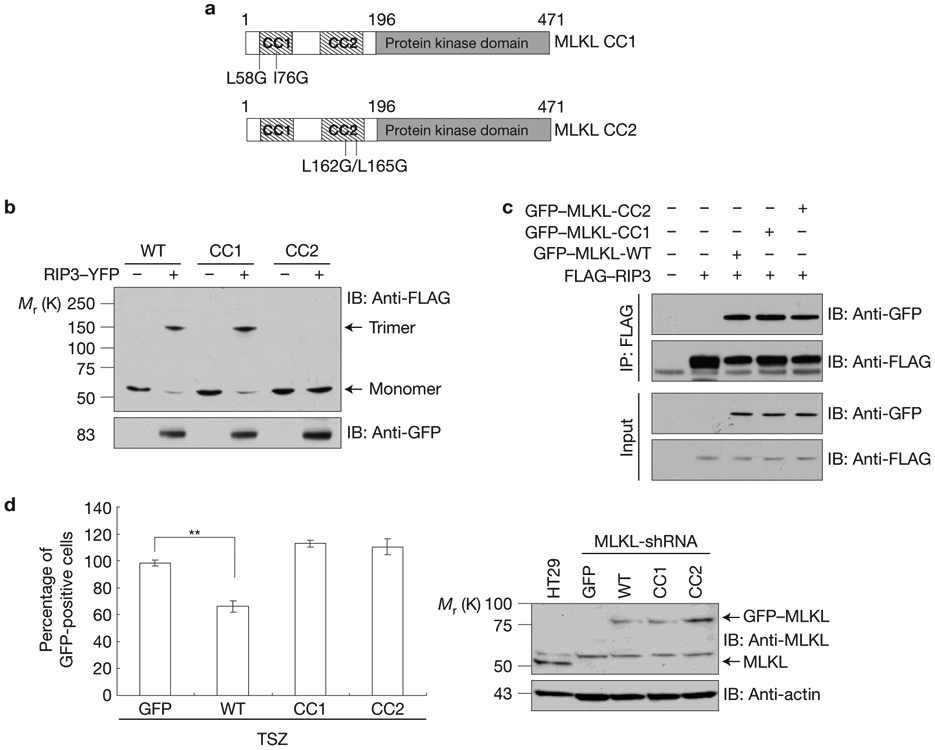

The coiled-coil domain 2 of MLKL is responsible for its trimerization

We next investigated whether MLKL trimerization is mediated by the two coiled-coil domains and whether the trimerization is important for MLKL to mediate necroptosis. To address these questions, we generated MLKL coiled-coiled domain 1 (CC1) and CC2 mutants by substituting glycine for the conserved leucine or isoleucine residues in these domains, CC1:L58G/I76G and CC2:L162G/L165G, respectively (Fig. 3a). These mutations disrupt the α-helices of these two coiled-coil domains and lead to a compromised secondary structure of these domains as predicted by the MultiCoil program. When these two mutant MLKL plasmids were expressed in HEK293 cells, MLKL CC2 mutant protein failed to trimerize whereas MLKL CC1 mutant protein was still able to form trimers efficiently as compared to WT MLKL (Fig. 3b). These results indicated that the CC2 domain is responsible for MLKL trimerization. As the carboxy-terminal kinase domain of MLKL mediates its interaction with RIP3, we examined whether these mutations in the coiled-coil domains affect MLKL interaction with RIP3 and found that both MLKL CC1 and CC2 mutant proteins interacted with RIP3 normally (Fig. 3c). To check whether these mutations in MLKL coiled-coil domains affect its function to mediate necroptosis, we expressed these mutant MLKL plasmids in HT29 MLKL-shRNA cells, in which the endogenous MLKL expression was knocked down by a specific MLKL-shRNA targeting its 3′UTR. Whereas the WT MLKL protein partially restored TNF-induced necroptosis in these cells, both MLKL CC1 and CC2 mutant proteins failed to do so although they were expressed at similar levels to the WT protein (Fig. 3d). It is surprising to see that the MLKL CC1 mutant protein did not reconstitute the sensitivity of these cells to necroptosis because it still trimerizes and interacts with RIP3. Therefore, it is possible that the CC1 mutations altered some other features of MLKL protein that is critical for its function in mediating necroptosis.

Figure 3.

The coiled-coil domain 2 of MLKL is responsible for its trimerization (a) Schematic of coiled-coil-defective mutant proteins of MLKL. The hatched rectangles represent the predicted regions of the coiled-coil domains, named CC1 and CC2. (b) HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG–MLKL, FLAG–MLKL-CC1 mutant or FLAG–MLKL-CC2 mutant with or without RIP3–YFP as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. (c) HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP–MLKL, GFP–MLKL-CC1 or GFP–MLKL-CC2 with FLAG–RIP3 as indicated. After 24 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (IP: FLAG) and analysed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG and anti-GFP antibodies. (d) Left, HT29 MLKL-shRNA cells were transfected with GFP, GFP–MLKL, GFP–MLKL-CC1 or GFP–MLKL-CC2 plasmids as indicated for 24 h, followed by treatment with TSZ for 24 h. Survival was determined by counting GFP+ cells and normalized to untreated cells. Results shown are averages ± s.d. from three independent experiments. Right, immunoblot analysis of MLKL and its mutants’ levels in HT29 cells or rescue MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells. All western data are representative of two or three independent experiments. **P < 0.01. Statistics source data for d can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

MLKL locates to plasma membrane in necroptosis

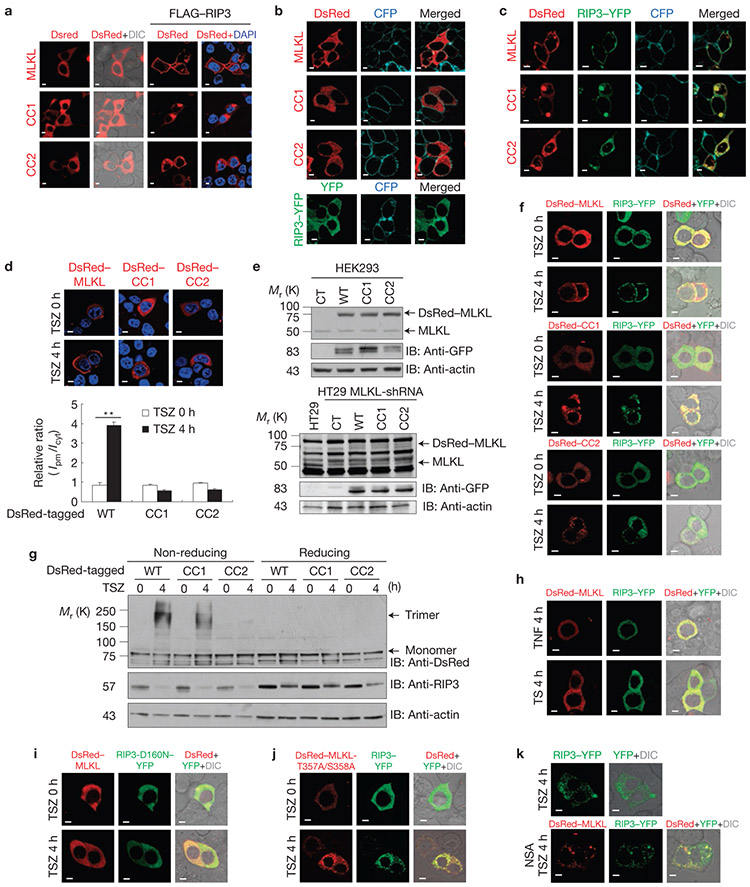

As protein localization is critical for function4, we next examined the cellular localizations of the WT and two mutant MLKL proteins. To do so, we first overexpressed DsRed-tagged WT MLKL and CC1 and CC2 mutants in HEK293 cells. We found that all three MLKL proteins localized evenly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4a). However, when these MLKL plasmids were co-transfected with FLAG–RIP3, which increases the trimerization of the WT and the CC1 mutant MLKL proteins (Fig. 2d), the two mutant MLKL proteins formed some aggregates in the cytoplasm and surprisingly, most of the WT MLKL moved to the edges of the transfected cells (Fig. 4a), indicating that the WT MLKL proteins may translocate to the plasma membrane in the presence of RIP3. As it is known that the RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms aggregates in the cytoplasm10,23, we then re-performed these experiments with RIP3–YFP instead of FLAG–RIP3 to examine whether only MLKL or both MLKL and RIP3 proteins locate to the plasma membrane. A CellLight Plasma Membrane–CFP was also included in these experiments as a control of plasma membrane localization. The overexpressed WT and the mutant MLKL proteins or RIP3 evenly localized in cytoplasm as reported previously10 (Fig. 4b). When RIP3 and MLKL proteins are co-transfected, the CC1 and CC2 mutant MLKL and RIP3 proteins remained in the cytoplasm and formed aggregates (Fig. 4c). Again, surprisingly, we found that not only MLKL but also RIP3 protein located to the plasma membrane as most of the MLKL and RIP3 proteins co-localized with the CFP–plasma membrane marker (Fig. 4c). To confirm that the plasma membrane translocation of MLKL and RIP3 proteins occurs during TNF-induced necroptosis, HT29 MLKL-shRNA cells were transfected with DsRed-tagged WT and mutant MLKL plasmids alone or were co-transfected with RIP3–YFP plasmid. Unlike in HEK293 cells, these proteins were expressed at levels lower or similar to their respective endogenous proteins in HT29 cells and do not form aggregates (Fig. 4d, upper panel and e). Whereas the MLKL CC1 and CC2 mutants and RIP3 formed aggregates in the cytoplasm following TSZ treatment, the WT MLKL alone or the WT MLKL and RIP3 together localized to the plasma membrane in response to TSZ (Fig. 4d, upper panel and 4f). To quantitatively determine the translocation of MLKL to the plasma membrane on necrotic induction, the ratio of the fluorescence intensity near the plasma membrane region versus the cytosolic region was determined by using line intensity profiles across selected cells of each sample24 (Supplementary Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 4d, lower panel, the relative intensity ratio of WT MLKL near the plasma membrane region versus the cytosolic region was greatly increased after TSZ treatment. However, no increase of the relative intensity ratio was observed in either MLKL-CC1- or CC2-mutant-transfected cells (Fig. 4d, lower panel). Furthermore, the trimerization of DsRed–MLKL and CC1 was also observed on TSZ treatment in MLKL shRNA HT29 cells (Fig. 4g). Therefore, CC1 mutation disrupts MLKL plasma membrane localization. Importantly, MLKL and RIP3 membrane localization is specific to necroptosis because TNF or TS treatment did not change their localizations in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4h). As in the case of MLKL trimerization, RIP3 kinase activity and MLKL phosphorylation are also essential for the membrane localization of MLKL (Fig. 4i,j). In addition, RIP3 membrane translocation requires a functional MLKL because knocking down MLKL or administering the chemical necrosulphonamide (NSA), which targets MLKL, abolished RIP3 translocation (Fig. 4k)10.

Figure 4.

MLKL locates to plasma membrane following necroptosis induction. (a) HEK293 cells expressing DsRed–MLKL, DsRed–MLKL-CC1 or DsRed–MLKL-CC2 with or without FLAG–RIP3 were analysed for subcellular localization by confocal imaging. (b,c) HEK293 cells expressing DsRed–MLKL, DsRed–MLKL-CC1 or DsRed–MLKL-CC2 with (c) or without (b) RIP3–YFP were analysed for co-localization with plasma marker (CellLight Plasma Membrane–CFP). (d) MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells were transfected with DsRed–MLKL, DsRed–MLKL-CC1 or DsRed–MLKL-CC2 and treated with or without TSZ as indicated. Upper panel, subcellular localization of MLKL and its mutants was imaged by confocal microscopy. Lower panel, relative fluorescence intensity ratio of plasma-membrane-adjacent area (Ipm) versus average cytosolic area (Icyt). Thirty transfected cells were analysed from each sample. Results shown are averages ±s.e.m. from three independent experiments. (e) Western blotting analysis of expression levels of DsRed–MLKL and RIP3–YFP in HT29 and HEK293 cells. (f) Representative images of MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells co-expressing DsRed–MLKL (upper panel), DsRed–MLKL-CC1 (middle panel) and DsRed–MLKL-CC2 (lower panel) with RIP3–YFP treated with TSZ. (g) Analysis of trimerization of DsRed–MLKL and DsRed-CC1 in cells from d. The cell lysates were resolved either on reducing or non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (h–j) Confocal imaging of the subcellular localization of MLKL and RIP3 in MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells co-expressing RIP3–YFP and DsRed–MLKL treated with TNF (h, upper panel) or TS (h, lower panel) or RIP3-D160N–YFP (i), or DsRed–MLKL-T357A/S358A (j). (k) Confocal imaging of the subcellular localization of MLKL and RIP3 in MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells transfected with RIP3–YFP and treated with TSZ (upper panel) or DsRed–MLKL plus RIP3–YFP and treated with TSZ plus NSA (lower panel) as indicated. Scale bar, 5 μm; DIC, differential interference contrast; DAPI was used as a nuclear staining marker; **P < 0.01. Statistics source data for d can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Scale bar, 10 μm. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

We then examined whether TSZ treatment leads to the translocation of the endogenous MLKL and RIP3 proteins in HT29 cells by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, both MLKL and RIP3 antibodies are not ideal for immunohistochemistry staining owing to their high background staining in MLKL and RIP3 knockdown cells, respectively. Nevertheless, TSZ-induced plasma membrane translocation of MLKL and RIP3 was detected in control shRNA cells. (Supplementary Fig. 3).

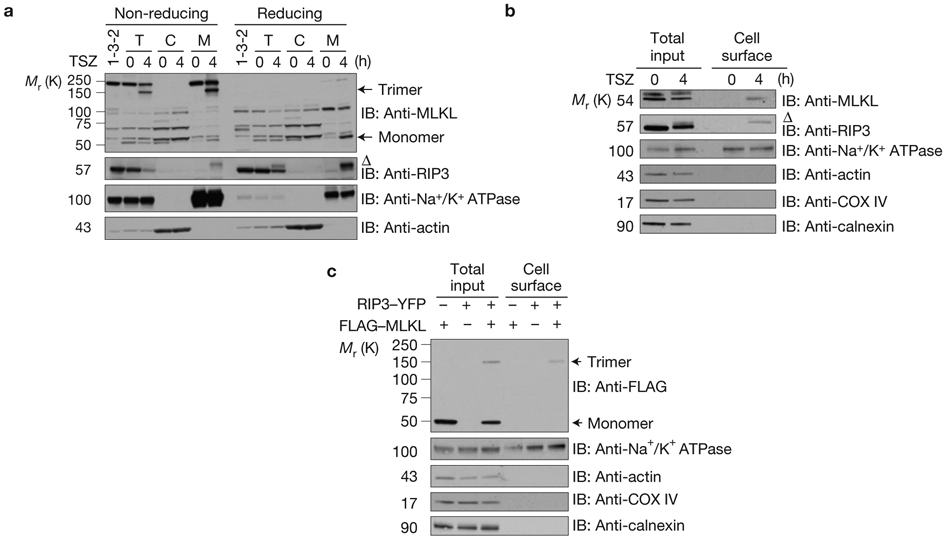

To biochemically prove the translocation of MLKL to the plasma membrane on necroptosis induction, we first separated the crude membrane and cytosolic fractions from HT29 cells with or without TSZ treatment. As shown in Fig. 5a, most MLKL detected in the crude membrane fraction of treated cells is trimeric. Consistent with our microscopy study, both MLKL and RIP3 are present in the crude membrane fraction (Fig. 4a). As most cell membrane fractionation approaches are contaminated with membrane-containing organelles such as mitochondria or ER, to provide more specific biochemical evidence, we then decided to use a cell surface protein isolation approach to examine whether MLKL and RIP3 are recruited to the plasma membrane. The rationale for this experimental design is that MLKL and RIP3 most likely interact with some transmembrane/cell surface proteins if they are recruited to the plasma membrane. As shown in Fig. 5b, when cell surface proteins were isolated, both MLKL and the phosphorylated RIP3 were detected in the sample of TSZ-treated cells but not in the sample of non-treated cells. In this experiment, Na+/K+ ATPase was used as a positive control for transmembrane/surface protein and actin, COX IV and calnexin were used as a control for cytosolic, mitochondrial and ER membrane proteins, respectively (Fig. 5b). Importantly, the membrane localization of MLKL and RIP3 was also detected when cell surface proteins were isolated from necrotic MEF and J774A.1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 4). When MLKL and RIP3 were overexpressed in HEK293 cells and the cell surface proteins were isolated and analysed under non-reducing conditions, only the trimerized MLKL was detected although there is more monomer MLKL protein detected in the total input control (Fig. 5c). This result further indicates that the trimerized MLKL locates at the plasma membrane.

Figure 5.

Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL in response to necroptosis induction. (a) Control shRNA or MLKL shRNA HT29 cells (clone 1-3-2) were treated with TSZ. The total, cytosolic and crude membrane fractions were resolved either on reducing or non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. T, total cell lysate. C, cytosolic fraction. M, membrane fraction. (b) HT29 cells were treated with TSZ as indicated. Total cellular lysate and the biotinylated, cell surface fraction were resolved on reducing gel and analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. (c) HEK293 cells were transfected as indicated. Total cellular lysate and the biotinylated, cell surface fraction were resolved on non-reducing gel and analysed by immunoblot as indicated. Δ indicates phosphorylated RIP3. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Taken together, these experiments suggest that the trimerized MLKL and RIP3 locate to the plasma membrane during TNF-induced necroptosis. These findings described in Figs 4 and 5 suggest that the plasma membrane localization of MLKL may be critical for its function to mediate TNF-induced necroptosis.

MLKL-mediated calcium influx is involved in plasma membrane rupture during necroptosis

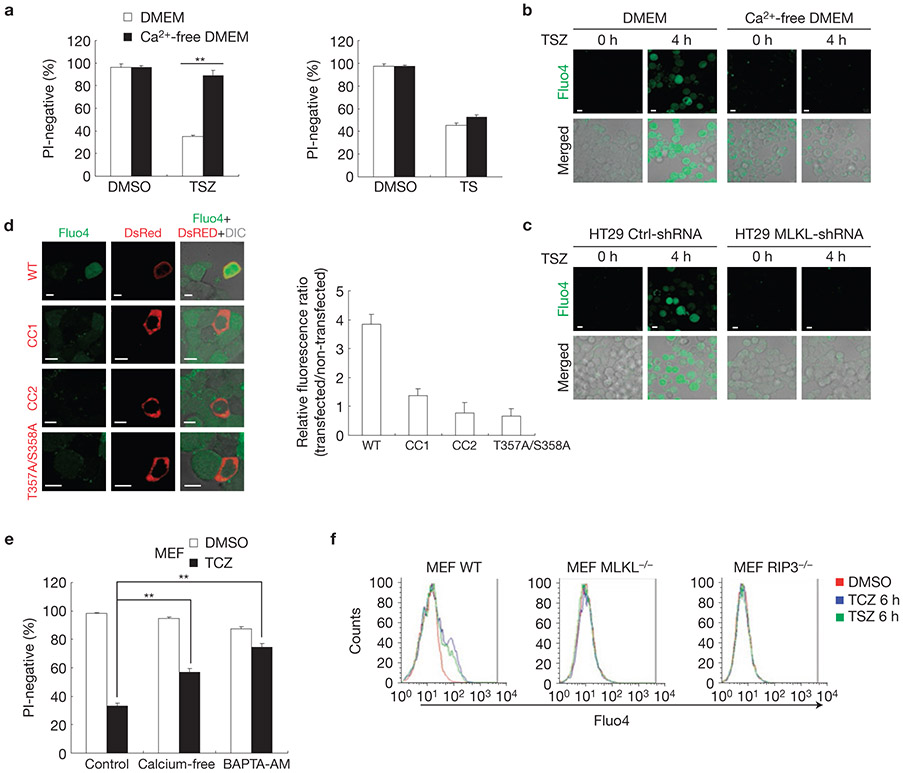

Next we investigated the potential mechanism of MLKL function at the plasma membrane during necroptosis. One of the unique features of necroptosis is the loss of plasma membrane integrity. However, considering that the plasma membrane rupture is a relatively late event, for example, at 8 h after TSZ treatment in HT29 cells, compared with MLKL plasma membrane translocation (3–4) h following necroptosis induction, we explored the possible immediate downstream event of MLKL translocation. As extracellular calcium influx has been suggested to play a role in necroptosis19, we decided to examine whether MLKL plasma membrane localization is required for calcium influx. We first confirmed that calcium influx is involved in necroptosis in HT29 cells as most of these cells were negative for propidium iodide (PI) staining under necroptosis but not apoptosis when they were cultured in calcium-free medium (Fig. 6a). To prove there is calcium influx during necroptosis, HT29 cells were loaded with the calcium indicator Fluo4. We found that Fluo4 fluorescence was markedly increased after 4 h of TSZ treatment in cells cultured in regular medium but not in calcium-free medium (Fig. 6b). Importantly, this calcium influx during necroptosis in HT29 cells requires MLKL because it was completely blocked in MLKL-shRNA cells or in NSA-treated cells (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 5a). The involvement of MLKL-mediated calcium influx in TSZ-induced membrane damage is further confirmed in JurkatFADD−/− and mouse J774A.1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, treating the cells with necrostatin-1 or knocking down RIP3 also blocked TSZ-induced calcium influx, suggesting that both RIP1 and RIP3 are required for calcium influx (Supplementary Fig. 5a). The defect of calcium influx in MLKL-shRNA cells following TSZ treatment was restored by the ectopic expression of the WT MLKL, but not the MLKL CC1, CC2 and MLKL T357A/S358A mutants (Fig. 6d). As the trimerization and the plasma membrane localization of MLKL and the phosphorylation of RIP3 were not affected under calcium-free conditions in TSZ-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 5b,c), these results indicated that calcium influx is a downstream event of MLKL trimerization and membrane localization.

Figure 6.

MLKL-mediated calcium influx is involved in plasma membrane rupture during necroptosis. (a) HT29 cells were cultured in DMEM with or without calcium and treated with dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) control, TSZ for 24 h or TS for 48 h. Cell survival was determined by PI staining. Results shown are averages ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. (b) HT29 cells were loaded with Fluo4 AM and then treated with TSZ in the presence of normal medium or calcium-free medium for 4 h. Representative confocal images of live HT29 cells are shown. (c) HT29 shRNA control cells or MLKL shRNA cells were loaded with Fluo4 AM and then treated with TSZ for 4 h. Representative confocal images of live HT29 cells are shown. (d) Left, HT29 MLKL-shRNA cells were transfected with DsRed–MLKL-WT, DsRed–MLKL-CC1, DsRed–MLKL-CC2 or DsRed–MLKL-T357A/S358A as indicated. After 24 h transfection, cells were loaded with Fluo4 and then treated with TSZ for 4 h. The representative confocal images are shown. Right, ratiometric measurement of Fluo4 mean fluorescence intensity between transfected and non-transfected cells (20 cells from each part). Results shown are averages ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. (e) MEF cells were cultured with or without calcium or pre-treated with BAPTA-AM (10 μm) for 30 min and then treated with TCZ for 13 h. Cell survival was determined by PI staining. Results shown are averages ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. (f) WT, MLKL-deficient or RIP3-deficient MEF cells were treated with TSZ or TCZ for 6 h. Cells were collected and loaded with Fluo4. Fluo4 fluorescent cells were determined by FACS analysis. **P < 0.01. Scale bar, 10 μm. Statistics source data for this figure can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

In our earlier study, we demonstrated that an important downstream event of MLKL during necroptosis is the generation of ROS (ref. 11). We now demonstrated that calcium influx is another important downstream event of MLKL during TNF-induced necroptosis. Although ROS plays a minimal role in necroptosis in HT29 cells, calcium influx is involved in plasma membrane damage of these cells. In other types of cell that are sensitive to TNF-induced necroptosis, such as U937 cells, both calcium influx and ROS are critical for MLKL to mediate necroptosis (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, the intracellular calcium release also contributes to TSZ-induced necroptosis in some types of cell, such as MEFs, because the deletion of extracellular calcium only marginally blocked TCZ-induced membrane damage in MEFs, but the cell-permeable calcium chelator BAPTA-AM, which decreases the total level of intracellular Ca2+, blocks membrane damage more efficiently (Fig. 6e). Nevertheless, MLKL and RIP3 are required for both extracellular calcium influx and the intracellular calcium release in MEFs (Fig. 6f).

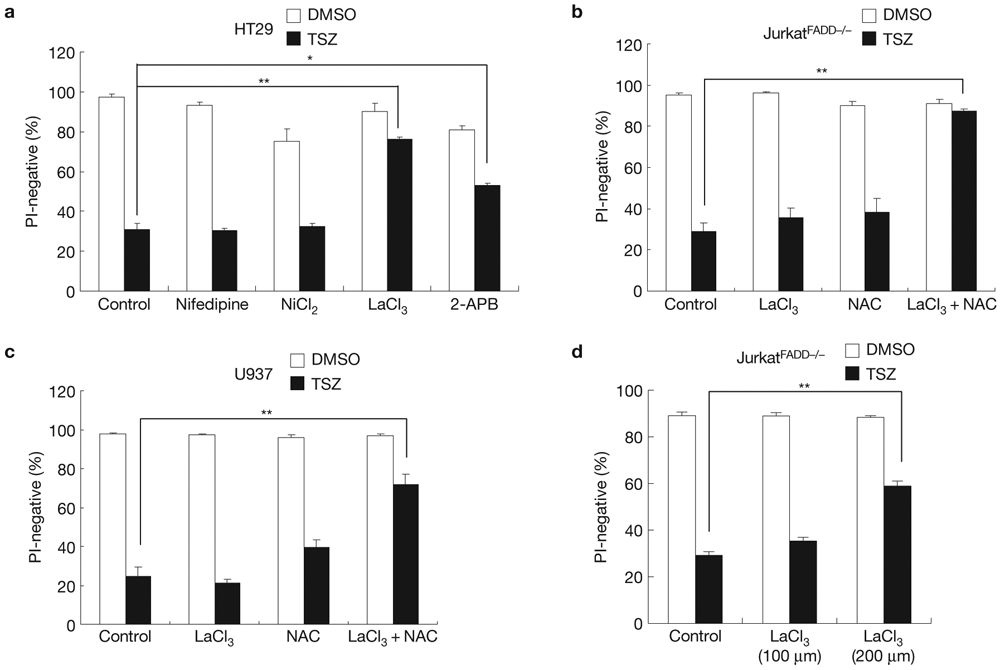

The calcium influx during necroptosis suggests that calcium channels in the plasma membrane may play a role in necroptosis. Therefore, we then tested which type of calcium channel is involved in necroptosis19. When we treated HT29 cells with the L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel blocker nifedipine, the T-type voltage-dependent calcium channel blocker NiCl2 or the non-voltage-sensitive channel blockers LaCl3 and 2-APB before administration of TSZ, we found that only the two non-voltage-sensitive channel blockers, LaCl3 and 2-APB, protected cells from TSZ-induced necroptosis (Fig. 7a). The non-voltage-sensitive channel blocker LaCl3 had a similar effect on TSZ-induced necroptosis in JurkatFADD−/− and U937 cells (Fig. 7b-d). These results indicated that the non-voltage-sensitive channels may function downstream of MLKL.

Figure 7.

Calcium channels are involved in necroptosis. (a) HT29 cells were treated with nifedipine (100 μm), NiCl2 (1 mM), LaCl3 (100 μm) or 2-APB (50 μm) and TSZ for 24 h. Cell survival was determined by flow cytometry of PI staining. (b,c) JurkatFADD−/− cells (b) or U937 cells (c) were pre-treated with LaCl3(100 μM), NAC (5 mM) or LaCl3 plus NAC. Then, the cells were treated with TSZ as indicated. After 10 h, cell survival was determined by PI staining. (d) JurkatFADD−/− cells were pre-treated with the increased concentration of LaCl3 (200 μM) and then treated with TSZ as indicated. After 10 h, cell survival was determined by PI staining. Results shown are averages ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistics source data for this figure can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

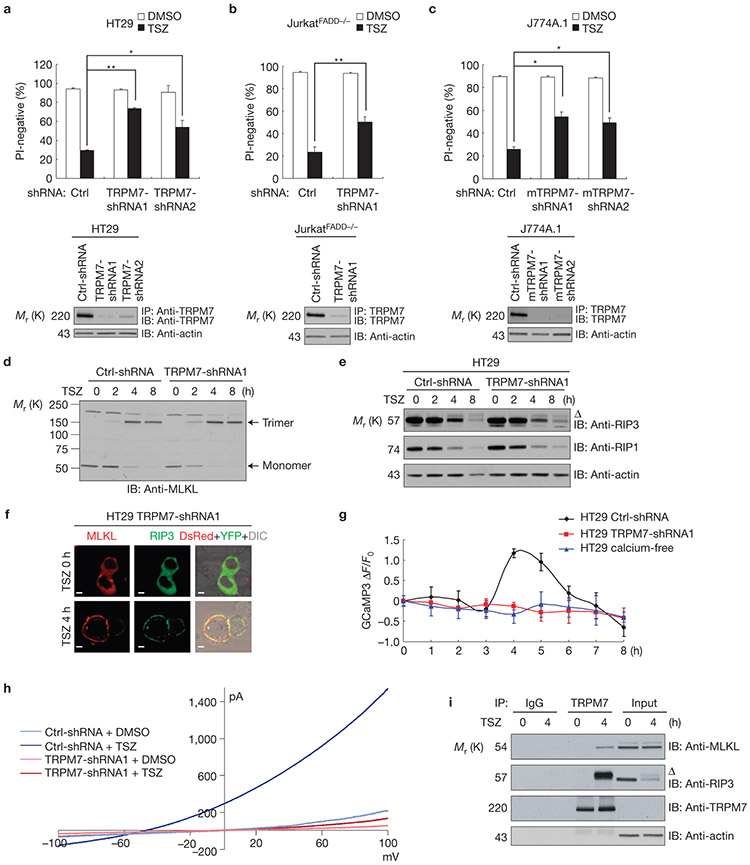

TRPM7 is involved in MLKL-mediated necroptosis

Among the known non-voltage-sensitive channels, TRPM7 has previously been implicated in necroptosis25-27. As TRPM7 is expressed in HT29 cells, we then tested whether TRMP7 is involved in TSZ-induced necroptosis and found that TRPM7 knockdown significantly protected HT29 cells from TSZ-induced necroptosis (Fig. 8a). Furthermore, the same protective effect was also observed in TRPM7-shRNA JurkatFADD−/− and TRPM7-shRNA J774A.1 cells on necrotic induction (Fig. 8b,c). Importantly, knocking down TRPM7 did not affect RIP3 phosphorylation and MLKL trimerization and plasma membrane localization following TSZ treatment (Fig. 8d-f). The decreased levels of RIP1 and RIP3 at 8 h after TSZ treatment in Fig. 8d are due to proteasome-mediated degradation of these two proteins. To confirm that TRMP7 is responsible for the calcium influx during necroptosis, a genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator, GCaMP3 (ref. 28), was used to monitor the Ca2+ level in live HT29 cells treated with TSZ. We found that the GCaMP3 fluorescent signal was markedly increased at 4 h after TSZ treatment in the control HT29 cells; however, no change of GCaMP3 fluorescent signal was detected in TRPM7 knockdown cells or in cells cultured in calcium-free medium (Fig. 8g). The actual representative images of these experiments are shown in Supplementary Videos 1–3. To further prove that a TRPM7-mediated current was induced by TSZ treatment, we performed patch-clamp recordings in both control shRNA and TRPM7 shRNA HT29 cells after 4 h of TSZ treatment. As shown in Fig. 8h, control shRNA cells treated with TSZ exhibited robust TSZ-induced currents, whereas TRPM7 knockdown significantly inhibited the increase of currents. These results indicated that TSZ triggered a TRPM7-dependent current in HT29 cells. As MLKL and RIP3 localize to the plasma membrane where the TRPM7 resides, we then examined whether MLKL and RIP3 are in the same complex with TRPM7 on necroptosis induction. By performing immunoprecipitation experiments with a TRPM7 specific antibody, we found that both MLKL and the phosphorylated RIP3 co-precipitated with TRPM7 after 4 hrs of TSZ treatment (Fig. 8i). Taken together, these results suggest that TRPM7 is a downstream component of MLKL and is responsible for the calcium influx and subsequent plasma membrane damage.

Figure 8.

TRPM7 is involved in MLKL-mediated necroptosis. (a–c) HT29 (a), JurkatFADD−/− (b) or J774A.1 (c) cells expressing control-shRNA or TRPM7-shRNAs were treated with or without TSZ for 24 h. Cell survival was determined by PI staining. Upper panel, results shown are averages ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments. Lower panel, TRPM7 protein levels were determined by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with anti-TRPM7 antibody. (d,e) Control-shRNA or TRPM7-shRNA HT29 cells were treated with TSZ as indicated. The cell lysates were resolved either on non-reducing (d) or reducing gel (e) and analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. (f) Representative confocal images of live TRPM7-shRNA HT29 cells co-expressing DsRed–MLKL and RIP3–YFP treated with TSZ at time 0 and 4 h. Scale bar, 5 μm. (g) The changes of GCaMP3 fluorescence in control-shRNA, MLKL-shRNA HT29 cells or HT29 cells cultured in calcium-free medium during TSZ treatment. Data are expressed as change of GCaMP3 fluorescence ΔF over basal fluorescence F0 at any given time. Results shown are averages ± s.e.m. in 10 cells. (h) Recording TSZ-induced current in control-shRNA or TRPM7-shRNA HT29 cells. I–V curve measurements were obtained after a 4 h TSZ treatment and averaged from the 10 cells in each experiment. (i) HT29 cells were treated with TSZ for 4 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-TRPM7 antibody. The immunoprecipitated complexes were analysed by immunoblotting as indicated. Δ indicates phosphorylated RIP3. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Scale bar, 10 μm. Statistics source data for this figure can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Uncropped images of western blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of TNF signalling has been intensively studied and, in particular, the regulation of TNF-induced apoptosis is well understood. However, the machinery of TNF-initiated necroptosis is still largely unknown. Our present data provide a mechanism of MLKL-mediated TNF-induced necroptosis, by which MLKL targets the RIP3 necrosome to the plasma membrane and regulates calcium influx through TRPM7. Our results demonstrate that MLKL needs to form trimers and to localize to the plasma membrane to mediate TNF-induced necroptosis. A recent study showed the structure of MLKL (ref. 29), which supports our finding that MLKL functions as a trimer.

Necroptosis is characterized by a rise in cytosolic Ca2+, increased ROS, intracellular acidification, a depletion of ATP, and ultimately plasma membrane rupture19. Our study demonstrates that the trimerized MLKL locates at the plasma membrane and causes TRPM7-mediated calcium influx. As TRPM7 was known as a cation channel, it is important to test whether other ions such as Na+ and Mg2+ may also play a role in necroptosis, particularly in cells that are not protected well by calcium-free medium, such as MEFs. Interestingly, a recent study reported that cations, particularly Ca2+, function as switches of amyloid-mediated membrane disruption30. As RIP1 and RIP3 form an amyloid-like complex23, it is possible that MLKL-mediated cations/Ca2+ influx triggers the necrosome to disrupt the plasma membrane. A previous study showed that the intracellular C terminus of TRPM7 was cleaved by caspase 8 during apoptosis31. It reported that the cleavage of TRPM7 increases its activity as a cation channel, but did not affect the Ca2+ influx. In our study, we showed that TSZ treatment leads to a marked increase of Ca2+ influx, which is regulated by MLKL/RIP3. Therefore, it is critical to study how RIP3/MLKL regulates TRPM7 activity in a future study.

PGAM5 was identified as a key mediator of necroptosis as it is involved in calcium ionophore-, ROS- and TNF-induced necroptosis20. However, because RIP3 and MLKL are needed for TNF-induced necroptosis, it is possible that PGAM5 is a downstream component of calcium influx and ROS generation in the necrotic pathway.

Taken together, our present results provide evidence that MLKL connects the RIP3 necrosome with the changes of the plasma membrane and the Ca2+ influx through a cation channel, TRPM7, in TNF-induced necroptosis. □

METHODS

Constructs, shRNAs, reagents and antibodies.

FLAG epitope-tagged human MLKL was described previously11. pEGFP-N1-RIP3 and pEGFP-N1-RIP3-D160N were provided by F. K. Ming Chan (University of Massachusetts Medical School, USA). FLAG–RIP3 was provided by J. Han (Xiamen University, China). pEYFP-N1-RIP3 and pEYFP-N1-RIP3-D160N were generated by subcloning RIP3 into pEYFP-N1 from RIP3–EGFP constructs. MLKL point mutants were generated using site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by sequencing analysis. These mutants were inserted into pCMV-Tag2A(FLAG), pDsRed-Monomer-C1 (DsRed) and pEGFP-C3(GFP) plasmids. GCaMP3 plasmid was a gift from L. Looger (Addgene plasmid #22692). All of the plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

The shRNA lentiviral plasmids were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The shRNA against MLKL corresponds to the 3′ untranslated region 1,936–1,956 relative to the first nucleotide of the start codon of human MLKL (GenBank accession number NM_152649). The shRNA MLKL 1-3-2 HT29 clone has been reported previously11. The shRNAs against human TRPM7 corresponded to the coding regions 1,312–1,332 and 5,948–5,968 (TRPM7-sh#1and TRPM7-sh#2, respectively) relative to the first nucleotide of the start codon of human TRPM7 (GenBank accession number NM_017672). The shRNAs against mouse TRPM7 corresponded to the coding regions 4,107–4,127 and 4,538–4,558 (TRPM7-sh#1 and TRPM7-sh#2, respectively) relative to the first nucleotide of the start codon of mouse TRPM7 (GenBank accession number NM_021450). The shRNA against human RIP3 corresponds to the coding region 1,490–1,510 relative to the first nucleotide of the start codon of human MLKL (GenBank accession number NM_006871).

TNFα and z-VAD-fmk were purchased from R&D. Cycloheximide was purchased from Sigma. Smac mimetic was a gift from S. Wang (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). Fluo4 was purchased from Invitrogen. NSA (necrosulphonamide) was purchased from ChemBridge. Antibodies were from commercial sources: anti-V5 (catalogue number: R960-25, Invitrogen); anti-FLAG (catalogue number, F9291; clone number, M2), anti-actin (catalogue number, A3853; clone number, AC-40), anti-GFP (catalogue number, G1544) and anti-MLKL (catalogue number, M6687) from Sigma; anti-DsRed (catalogue number, 632496; Clontech); anti-TRPM7 (catalogue number, 75-114; clone number, N74/25; NeuroMab); anti-RIP3 (catalogue number, ab72106; Abcam); anti-RIP1 (catalogue number, 610459; clone number, 38; BD Biosciences). Antibody against mouse MLKL was provided by J. Han (Xiamen University, China).

Cell culture.

HT-29, HEK293, mouse J774A.1 and MEF cells were cultured in DMEM. JurkatFADD−/− and U937 cells were cultured in RPMI1640. WT and RIP3-deficient MEF cells were generated from day 14 embryos of the same litter of RIP3 heterozygous breeding32. WT and MLKL-deficient MEF cells were provided by J. Han (Xiamen University, China)33. All media were supplemented with 10% FBS (vol/vol), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 units ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin. The stable HT29 MLKL-shRNA 1-3-2 clone was described previously11.

Lentivirus infection.

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pCMV-VSV-G and pCMV-dr8.2-dvpr and either non-targeting or MLKL-shRNA or TRPM7-shRNA plasmids. After 24 h, supernatant was collected and this lentiviral preparation was used to infect cells. After 24 h of infection, cells were selected with puromycin for a further 48 h.

Necroptosis induction and calcium-free medium treatment.

Necroptosis was induced by pretreatment with z-VAD-fmk (20 μM) and Smac mimetic (10 nM) or cycloheximide (10 μg ml−1) for 30 min and followed by TNFα (30 ng ml−1) for the indicated time periods. Apoptosis was induced by TNFα(30 ng ml−1) and Smac (10 nM) for the indicated time periods. Calcium-free DMEM was purchased from Invitrogen. Calcium-free RPMI1640 was purchased from USbiological. For calcium-free medium treatment, HT29, MEF and J774A.1 cells were pre-incubated with calcium-free medium together with z-VAD-fmk and Smac mimetic for 30 min and followed by TNFα for the indicated time periods. For JurkatFADD−/− and U937 cells, cells were pre-incubated with calcium-free medium overnight (12 h) and then treated with z-VAD-fmk, Smac mimetic and TNFα for the indicated time periods.

Crude cell membrane fraction.

HT-29 cells (2.5 × 106 cells) were detached from the culture plates with a non-enzymatic lifting solution consisting of HBSS with 1 mM EDTA and washed twice with PBS. Cells were re-suspended in 1 ml of the fractionation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES at pH 7.4, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM EGTA) and placed on ice for 10 min. Cells were disrupted by freezing with liquid nitrogen for 5 min and then were thawed on ice, repeated three times. The lysates were passed through a 25 G needle (BD Biosciences) ten times. Nuclei and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 750g for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged again at 10,000g for 5 min. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000g in an Optima TLX Ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter) for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant containing cytosolic proteins were concentrated using an acetone precipitation method. The pellets containing membrane proteins were washed with the fractionation buffer and were re-centrifuged at 100,000g for 45 min. The pellets were resuspended in M2 buffer and resolved in 4–20% SDS–polyacrylamide gels for western blot analysis.

Cell surface protein isolation.

Surface biotinylation was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with modifications using the Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit (Pierce). Briefly, HT-29 cells (3 × 107 cells) were washed three times with ice-cold PBS solution and incubated with a crosslinking reagent (DSP, 2 mM) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, buffer for 15 min to quench the reaction. Then, a membrane-impermeable biotinylation reagent sulpho-NHS-SS-biotin (0.2 mg ml−1 in PBS buffer) was added and incubated for 30 min on ice with gentle shaking. The reaction was stopped, cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS, and biotinylated proteins from the cell surface were isolated from lysates by incubation with immobilized streptavidin–agarose beads. A sample of the initial cell lysate was retained for analysis of total proteins. The biotinylated proteins were eluted from the beads using SDS–PAGE sample buffer containing 50 mM DTT. All of the eluted proteins and 0.2% of the total proteins were separated on SDS–PAGE for immunoblot analysis.

For HEK293 cell surface biotinylation, the cells (1 × 107 cells) were washed and directly incubated with biotinylation reagent for 30 min on ice with gentle shaking. Cells were lysed without SDS and incubated with immobilized streptavidin–agarose beads. The biotinylated proteins were removed from the beads by boiling in SDS–PAGE sample buffer without DTT for 5 min. All of the eluted proteins and 0.2% of the total proteins were separated on SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions, and proteins were quantified by immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblotting, crosslinking and immunoprecipitation.

Cells were collected and lysed in M2 buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7, 0.5% NP40, 250 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 3 mM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 20 mM glycerol phosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate and 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin). Cell lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and analysed by immunoblotting. For non-reducing gel analysis, cells were lysed in M2 buffer without DTT and separated by SDS–PAGE without β-mercaptoethanol. The dilution ratio of the antibodies used for western blotting is 1:1,000. The proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence, according to the manufacturer’s (Amersham) instructions.

For immunoprecipitation, lysates were precipitated with antibody (1 μg) and protein G-agarose beads by incubation at 4 °C overnight. Beads were washed four to six times with 1 ml M2 buffer, and the bound proteins were removed by boiling in SDS buffer and resolved in 4–20% SDS–polyacrylamide gels for western blot analysis.

For TRPM7 endogenous immunoprecipitation, crosslinking of cellular proteins was performed before the cell lysis. Cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS solution and incubated with a crosslinking reagent (DSP, 2 mM) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, buffer for 15 min to quench the reaction. Then, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 0.1% SDS and the samples were used in regular immunoprecipitation procedure as described above. All western data are representative of two or three independent experiments.

Confocal imaging and analysis.

HT29 or HEK293 cells were cultured in a 4-well chamber slide (Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide system) for 24 h and transfected with 0.2 μg pDsRed–MLKL and 0.2 μg pEYFP–RIP3 or FLAG–RIP3 by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 h post-transfection, HT29 cells were treated with TNFα/Smac mimetic/ z-VAD-fmk and plated in a 37° imaging station chamber. For imaging WT and mutant DsRed–MLKL with RIP3–YFP in HEK293 cells, transfected cells were directly visualized by confocal microscopy. For membrane localization analysis, 5–10 random fields (based on total counted cell number) were selected in each slide and a total of 30 cells were counted for membrane localization analysis. To quantify the fluorescence intensity ratio between the plasma membrane and cytosol in HT29 cells, a line (5 μm) was drawn across each one of the cells. The line intensity profiles were obtained by using a linescan program (MetaMorph). The results shown are averages ± s.e.m. from three independent experiments.

For immunofluorescence staining of endogenous MLKL and RIP3, HT29 cells were plated on coverslips in 24-well plates in complete media. The next day, cells were washed three times with PBS followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (in PBS) for 12 min at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with PBS after fixation. Cells were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 (in 0.02% BSA/PBS) for 2 min at room temperature and washed again three times with PBS. The cells were incubated for 10 min with blocking reagent (20% goat serum in 2% BSA/PBS) then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies for 1 h: rabbit polyclonal anti-human MLKL (1:50), or rabbit polyclonal anti-human RIP3 (1:250). The cells were washed three times in PBS, and then incubated with the FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies and rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin for 30 min, followed by DAPI for 5 min. Cells were washed three times with PBS and mounted on slides using Fluorogel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Stained cells were observed on a Zeiss AxioObserver.Zl microscope equipped with a PlanApo x63/1.4 oil DIC III objective. Representative confocal images were generated on a Zeiss LSM510 META laser scanning microscope (Zeiss). All confocal images are representative of three independent experiments.

Fluo4 and GCaMP3 Ca2+ imaging.

Cells were loaded with 2 μM Fluo4 AM in the HEPES-buffered saline solution (HBSS) containing (in mM): 134 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.0 MgSO4, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.8 CaCl2, 20 HEPES and 5 d-glucose (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 30 min. For cells cultured in calcium-free medium, CaCl2 was depleted from HBSS solution. For fluorescence imaging, cells were excited at 488 nm, emission was detected at 505–550 nm and a DIC transmission image was acquired simultaneously. A Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope with a ×63 oil objective was used for imaging. The Fluo4 fluorescence intensity was measured by Image J (NIH). For Fluo4 flow cytometry analysis, Fluo4-loaded cells were detached with a non-enzymatic lifting solution consisting of HBSS with 1 mM EDTA and washed twice with HBSS. Cells were suspended in HBSS buffer with or without calcium and analysed by flow cytometry on a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and with a 530 nm detection channel.

The stabilized GCaMP3 HT29 cells were established by transfecting HT29 cells with GCaMP3 construct and selecting with G418 (1.5 mg ml−1) for 1 week. The fluorescence intensity at 488 nm (F488) was monitored using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope with an incubator chamber. Time-lapse Ca2+ imaging was carried out for 8 h with 10 min intervals. Three independent experiments were performed and representative data in one experiment were expressed as the change in GCaMP3 fluorescence ΔF over the basal fluorescence F0 at any given time. All confocal images are representative of three independent experiments.

Electrophysiology.

Control shRNA or TRPM7 shRNA HT29 cells were treated with dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) or z-VAD-FMK (TSZ) for 4 h. Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed at 4 h after TSZ treatment. The I–V relationship was obtained with a 500 ms voltage ramp pulse applied from −100 mV to +100 mV. The holding potential was 0 mV. The extracellular solution (ECF) contained (in mM): 140 Gluta-NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 25 HEPES and 33 glucose. The pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette solution contained (in mM): 145 Cs-methanesulphonate, 8 NaCl, 5 ATP, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 4.1 CaCl2 and 10 HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH.

Cell rescue and survival assay.

For cell rescue assay, HT29 cells were infected with MLKL-shRNA against the 3′ untranslated region of MLKL. After selection with puromycin for a further 48 h, these HT29 MLKL shRNA cells were transfected with the GFP-tagged MLKL, CC1 or CC2 plasmids (0.2 μg per well in a 6-well plate) as indicated in Fig. 3d and then treated with TSZ or DMSO for a further 24 h. All GFP-positive cells were counted by flow cytometry from 10,000 events in each transfection. Cell survival was determined by comparing GFP-positive cells from TSZ-treated wells with the DMSO-treated control wells in each transfection. The normalization equation is as follows:

Data represent three independent experiments.

For cell death analysis, cells were treated with different reagents as indicated and then stained with PI (1 μg ml−1) for 5 min. A total of 10,000 cells were counted by PI flow cytometry and cell survival was determined as PI-negative population. Three independent experiments were performed.

Statistical analysis.

A Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used for comparison among all different groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank J. Han for MLKL-deficient MEF cells and MLKL antibody, and L. Looger for GCaMP3 plasmid. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

METHODS

Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper.

Note: Supplementary Information is available in the online version of the paper

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial Interests.

References

- 1.Chen G & Goeddel DV TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science 296, 1634–1635 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashkenazi A & Dixit VM Apoptosis control by death and decoy receptors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 11, 255–260 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR & Karin M Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe T & Kroemer G Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 11, 700–714 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christofferson DE & Yuan J Necroptosis as an alternative form of programmed cell death. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 22, 263–268 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green DR, Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R & Salvesen GS RIPK-dependent necrosis and its regulation by caspases: a mystery in five acts. Mol. Cell 44, 9–16 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho YS et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He S et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell 137, 1100–1111 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang DW et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science 325, 332–336 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun L et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao J et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5322–5327 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Donnell MA et al. Caspase 8 inhibits programmed necrosis by processing CYLD. Nat. Cell Biot 13, 1437–1442 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayan N et al. The NAD-dependent deacetylase SIRT2 is required for programmed necrosis. Nature 492, 199–204 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mocarski ES, Upton JW & Kaiser WJ Viral infection and the evolution of caspase 8-regulated apoptotic and necrotic death pathways. Nat. Rev. Immunol 12, 79–88 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welz PS et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 477, 330–334 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H et al. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature 471, 373–376 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberst A et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature 471, 363–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin Y et al. Tumor necrosis factor-induced nonapoptotic cell death requires receptor-interacting protein-mediated cellular reactive oxygen species accumulation. J. Biol. Chem 279, 10822–10828 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zong WX & Thompson CB Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 20, 1–15 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Jiang H, Chen S, Du F & Wang X The mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 functions at the convergence point of multiple necrotic death pathways. Cell 148, 228–243 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolf E, Kim PS & Berger B MultiCoil: a program for predicting two- and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 6, 1179–1189 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degterev A et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat. Chem. Biol 1, 112–119 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell 150, 339–350 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oancea E, Teruel MN, Quest AF & Meyer T Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged cysteine-rich domains from protein kinase C as fluorescent indicators for diacylglycerol signaling in living cells. J. Cell Biol 140, 485–498 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aarts M et al. A key role for TRPM7 channels in anoxic neuronal death. Cell 115, 863–877 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNulty S & Fonfria E The role of TRPM channels in cell death. Pflugers Arch. 451, 235–242 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bates-Withers C, Sah R & Clapham DE TRPM7, the Mg(2+) inhibited channel and kinase. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 704, 173–183 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian L et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods 6, 875–881 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy JM et al. The pseudokinase MLKL mediates necroptosis via a molecular switch mechanism. Immunity 39, 443–453 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sciacca MF et al. Cations as switches of amyloid-mediated membrane disruption mechanisms: calcium and IAPP. Biophys. J 104, 173–184 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desai BN et al. Cleavage of TRPM7 releases the kinase domain from the ion channel and regulates its participation in Fas-induced apoptosis. Dev. Cell 22, 1149–1162 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton K, Sun X & Dixit VM Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol. Cell Biol 24, 1464–1469 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu J et al. Mlkl knockout mice demonstrate the indispensable role of Mlkl in necroptosis. Cell Res. 23, 994–1006 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.