Abstract

Much of the research exploring the experiences of family caregivers of people with dementia has focussed on spouses and adult children. It is hypothesised that other family members at different life stages and with different family roles may experience and perceive the caregiving role differently. The objective of the current review was to explore the experiences of grandchildren who provide care to a grandparent with dementia. A systematic search of four databases identified 12 studies which met the inclusion criteria. An assessment of quality was completed for each of the included studies. Grandchildren described dementia-related changes, changes to their role and relationship with their grandparent, multiple impacts of caregiving, influences of other family relationships on caregiving and positive aspects of caregiving. Many of the included studies met most of the quality criteria for the respective methodological design; however, there was some variation in quality and sample across included studies. The review indicates that assessments and interventions to incorporate grandchildren and the wider family system may help to support family carers to continue to provide care for grandparents with dementia. The research and clinical implications and limitations of the review are also considered.

Keywords: dementia, grandchildren, grandparents, carers, experiences

Introduction

Dementia and caregiver stress

The dementia caregiving literature has identified the complexity and diversity of caregiving experiences. In the past, researchers tended to focus their investigations on the negative aspects of caregiving including caregiver burden and the physical and psychosocial impacts of caregiving. However, more recent research has explored the positive aspects of caregiving such as positive experiences, satisfactions, growth and rewards (Doris et al., 2018; Lloyd et al., 2016). Quinn and Toms (2019) found that recognising positive aspects of caregiving was related to improved carer well-being. Therefore, considering both the positive and negative dimensions of caregiving experiences may provide a more balanced picture of the diversity and individuality of caregiving experiences. Furthermore, interventions which support caregivers to have more positive experiences of providing care may be helpful (Quinn & Toms, 2019).

The type of dementia, progressive nature, cognitive impairments and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia may influence caregiving experiences and the subsequent emotional impact on caregivers (Gilhooly et al., 2016; Schulz & Sherwood, 2008). Research has found that some caregivers of people with dementia experience caregiving-related stress, depression or anxiety (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009). Demographic factors such as carer age, gender and length of time caring have been associated with higher levels of carer stress (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009; Chappell et al., 2015; D’Onofrio et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2012; Lou et al., 2015). Other predictors of caregiver stress have been identified to include higher functional impairment, number of hours spent completing caregiving tasks and a spousal relationship between the caregiver and care recipient. The roles and responsibilities held by caregivers, such as their work, relationships and other family commitments, may also impact on caregiving experiences. Consequently, there has been an increased focus on identifying possible interventions to support family members to maintain their caregiving role and reduce the need for care recipient admission into long-term care (Luppa et al., 2008).

Relationships between caregiver and care recipient

Much of the research on the experiences of family carers of people with dementia has focussed on spouses and adult children which form two of the most common groups of family caregivers for people with dementia (La Fontaine et al., 2016). The literature has indicated that different family members can experience the caregiving role in diverse ways (Kim et al., 2012; Raschick & Ingersoll-Dayton, 2004). Whilst some studies have focussed on the experiences of these groups individually, others have compared the two groups to identify similarities and differences in caregiving experiences. For example, McAuliffe et al. (2018) found that perceived burden was related to depression in spouse and adult child caregivers; however, social support and mastery significantly mediated this relationship for spouse caregivers. Simpson and Carter (2013) compared the experiences of wives and daughters providing care and found that caregiving mastery was associated with stress and depression in wives. This suggests that carers may have different expectations and demands on their role as a caregiver dependent on their relationship with the care recipient.

Grandchildren as caregivers

Whilst spouses and adult children are the most common family caregivers of people with dementia, other relatives may also provide care, either as a primary or auxiliary caregiver (La Fontaine et al., 2016). A survey in 2010 found that 4% of informal family carers in England provide care to a grandparent (The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2010). Fruhauf and Orel (2008) highlighted the paucity of research investigating the experiences of grandchildren who provide care to their grandparents as primary, secondary or auxiliary caregivers. These researchers explored the experiences of grandchildren who provide care to their grandparents, including how their developmental level can influence coping strategies; however, this study was not specific to grandparents with a diagnosis of dementia.

There has been relatively little research exploring the caregiving experiences of grandchildren who have a grandparent with a diagnosis of dementia. It has been highlighted that the relationship between grandchildren and grandparents can be unique because of the multiple roles that grandparents can play during childhood, adolescence and adulthood including supportive, caregiving and educative roles (Hodgson, 1992; Roberto & Stroes, 1992; Weston & Qu, 2009). Strong grandchild–grandparent relationships have also been found to have a positive influence on the psychological well-being of grandchildren (Ruiz & Silverstein, 2007). Grandchildren may also be at a different stage in their own lives and face different demands when providing care for grandparents, compared to spouses and adult children (Dellmann-Jenkins et al., 2000). As a result, the current systematic review aims to address this gap in the literature by focussing on the experiences of grandchildren and great-grandchildren who provide care for their grandparent or great-grandparent with a diagnosis of dementia. The current review will use the term ‘grandchild’ to refer to both grandchildren and great-grandchildren and ‘grandparent’ to refer to both grandparents and great-grandparents, to be consistent with the reporting methods of the included studies when referring to these groups.

Method

Search strategy

The systematic review was conducted by searching the following online databases: PsycINFO, Medline, Scopus and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The initial literature search was conducted on 22 August 2019 and was repeated on 20 December 2019 to ensure that all eligible studies published up until this date were included in the current review. A total of 58 records were identified using the following search terms: grandchild* OR granddaughter* OR grandson* AND care* OR caregiv* AND grandparent* OR grandmother* OR grandfather* OR grandad* OR grandpa* OR grandma* OR nan* AND dementia OR Alzheimer*. Search limiters were not used as the scoping search identified a relatively small number of records to review. No date limit was set. The protocol for this review was prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number: CRD42019161949 (Venters & Jones, 2019).

Study selection criteria

The inclusion criteria to identify appropriate studies included that study participants were grandchildren or great-grandchildren of a grandparent with a diagnosis of dementia. If the study included other family relationships, then it was necessary that data for grandchildren or great-grandchildren could be extrapolated from the data. Studies that adopted a qualitative, quantitative or mixed method design were suitable for inclusion. Studies were excluded if they were not published in peer-reviewed journals and were not written in English. Review papers and case study designs were also excluded. Studies which explored other conditions as well as dementia were excluded when it was not possible to separate data related to dementia.

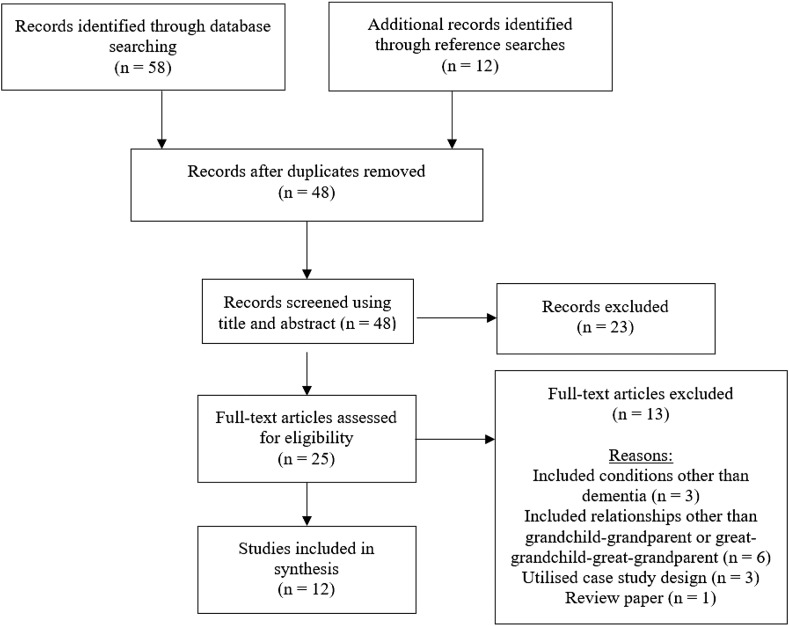

Fifty-eight articles were identified using this search strategy. The reference lists of the studies that met inclusion criteria were searched to identify further studies which met the aims of the review. A further 12 records were identified using this method. After duplicates were removed, a total of 48 records were screened to determine eligibility using the title and abstract. The full text of 25 articles was assessed and reasons for exclusion are provided (Figure 1). A total of 12 articles were included in the current review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram displaying the process of study selection (Moher et al., 2009). PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018) as it can be used to compare quality across varied study designs. The MMAT provides two screening questions regarding research questions and data gathered which are relevant to all studies. The follow-up questions are determined by the methodological design (Table 1). To ensure inter-rater reliability, the quality of 25% of the included studies was assessed by both authors. Where differences in opinion existed, the scoring was discussed until consensus was agreed.

Table 1.

Results of the quality appraisal for included studies.

| Category of study design | Quality criteria | Celdrán et al. (2009) | Celdrán et al. (2011) | Celdrán et al. (2012) | Celdrán et al. (2014) | Creasey and Jarvis (1989) | Creasey et al. (1989) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening questions | Are there clear research questions? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Qualitative | Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | ✓ | |||||

| Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | ✗ | ||||||

| Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | ✓ | ||||||

| Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | ✓ | ||||||

| Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | ✓ | ||||||

| Quantitative non-randomised | Are the participants representative of the target population? | ✗ | |||||

| Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and exposure? | ✓ | ||||||

| Are there complete outcome data? | ✓ | ||||||

| Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | ✓ | ||||||

| During the study period, has the exposure occurred as intended? | ✓ | ||||||

| Quantitative descriptive | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | ✓ | |||||

| Is the sample representative of the target population? | ✗ | ||||||

| Are the measurements appropriate? | ✓ | ||||||

| Is the risk of non-response bias low? | Can’t tell | ||||||

| Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | ✓ | ||||||

| Mixed methods | Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed method design to address the research question? | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | |||

| Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Are outputs of integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Data extraction and analysis

The analysis for the present review was based on the principles of narrative synthesis (Popay et al., 2006). This method was selected due to the proportion of included studies that adopted a qualitative or mixed method design, and to enable the assimilation of themes from each study. All articles were read and reread to identify the main concepts and themes. The study characteristics, themes and findings were extracted and tabulated (Table 2). Each study was considered in relation to relative strengths and weaknesses identified by the quality appraisal. The similarities and differences and relationships within and between studies were explored to identify common themes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author(s) and date | Country | Design | Objective | Sample (n, characteristic) | Characteristic of grandparent | Measure | Data analysis | Main result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celdrán et al. (2009) | Spain | Mixed methods design | 1. To explore the lessons that GC1 with a GP2 with dementia have learnt 2. To identify coping strategies that GC would recommend to others in similar situations |

N = 138 GC (87 women and 51 men) Age range: 14–21 years (M = 17.77, SD = 2.35) 31 of the GC were living with their GP |

GP had diagnosis of dementia and lived in the community (65.2%) or nursing home (34.8%) Age range: 67–97 years (M = 80.49, SD = 5.51) 67.4% were grandmothers |

Demographic questions. One sentence completion item: “I would say that the fact that my GP has dementia has taught me…” and one open-ended question: “What advice would you give to a person of your age who also had a GP with dementia?” Global deterioration scale (GDS) score for GP from nursing homes and day centres |

Thematic analysis used to analyse responses Binary logistic regression used to compare differences in responses based on participant demographics |

Five themes identified for lessons learnt were attitude towards life, personal changes, reflection on ageing, importance of family and knowledge of disease. Four themes identified for coping strategies were acceptance, actions towards GP, care/help and affection. Older GC cited more responses related to personal changes and reflections on ageing. Likelihood of GC identifying some lessons learnt differed with GC age, dementia severity on GDS, GP living in nursing home and GC gender |

| Celdrán et al. (2011) | Spain | Mixed methods design | 1. To explore emotions that GC experience when their GP has dementia 2. GC’s perception of current relationship with GP with dementia 3. GC’s perceptions of changes in relationship with GP with dementia |

N = 145 GC (89 women and 56 men) Age range: 14–21 years (M = 17.74, SD = 2.35) 31 of the GC were living with their GP |

GP had diagnosis of dementia and lived in the community (65.5%) or nursing home (34.5%) Age range: 67–96 years (M = 80.39, SD = 5.52) 68.3% were grandmothers |

Demographic questions. 15 questions developed by researcher to assess emotions GC experience in relation to GP. Questions to assess previous relationship with GP, five-point scales to assess current and previous satisfaction with relationship, frequency of contact and emotional closeness. Questions regarding changes to relationship with GP. GDS score for GP from nursing homes and day centres | Qualitative data were analysed using content analysis Quantitative data were analysed using principal components analysis, t test, chi-square test and Mann–Whitney U test |

1. GC reported mixed emotions. Positive emotions associated with satisfaction of supporting care for GP were most frequently reported. GC also described loss and guilt 2. Frequency of contact, emotional closeness and satisfaction varied 3. The majority of GC reported no changes in relationship, but reported reduced frequency of contact, emotional closeness and satisfaction with relationship. GC with higher intimacy with GP prior to onset of dementia tended to report greater decline in relationship. The main reason GC cited for changes to relationship was dementia |

| Celdrán et al. (2012) | Spain | Mixed methods design | 1. GC’s perceptions of changes to life due to GP’s dementia 2. GC’s perceptions of changes in relationship with parents and effect on GC-GP relationship 3. GC’s perceptions of changes in relationship with spouse of GP with dementia |

N = 145 GC (89 women and 56 men) Age range: 14–21 years (M = 17.74, SD = 2.35) 31 of the GC were living with their GP |

GP had diagnosis of dementia and lived in the community (65.5%) or nursing home (34.5%) Age range: 67–96 years (M = 80.39, SD = 5.52) 68.3% were grandmothers |

Demographic questions. Author composed open-ended questions and close-ended questions using four-point scales to assess how GC perceived their life to be different than peers, how dementia affected the GC’s relationship with parents and how parents affected the GC–GP relationship. Questions to assess the GC’s relationship with the spouse of GP with dementia – how dementia affected relationship, direction of change and reasons for perceived changes | Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis Quantitative data were analysed using cross-sectional analysis - t test, chi-square test and Mann–Whitney U test |

1. GC did not report many changes to life when comparing to peers. GC reported caring to have more of an effect on life due to daily activities, stress of primary caregivers and deterioration when living with GP. Positive changes included learning and maturity 2. Most changes were positive including support and increased communication. Most GC reported parents had a positive impact on GC–GP relationship – facilitating interactions and modelling coping 3. Positive changes included feeling closer to healthy GP and providing support. Negative changes included responses to dementia-related difficulties and reduced contact |

| Celdrán et al. (2014) | Spain | Qualitative design using free text sentence completion | To explore how GC perceive their GP with dementia, including their best and worst qualities, and how GC remember their GP in the past, including their best memories |

N = 145 GC (89 women and 56 men) Age range: 14–21 years (M = 17.74, SD = 2.35) 31 of the GC were living with their GP |

GP had diagnosis of dementia and lived in the community (65.5%) or nursing home (34.5%) Age range: 67–96 years (M = 80.39, SD = 5.52) 68.3% were grandmothers |

Demographic questions. Author composed questions to obtain data regarding frequency of contact and activities that GC does with GP. Sentence completion items regarding the GC’s perceptions of their GP, including their best and worst qualities, and the GC’s best memory of their GP. | Qualitative data were analysed using content analysis | Three categories identified regarding GP’s best qualities, including stable qualities of GP (extraversion, kindness, affection, strength and other), the GC–GP relationship (intimacy, aspects of care and past positive traits that dementia may have affected) and other (qualities affected by dementia). Four categories of worst qualities including grandparent’s qualities (irritability, inflexibility, passivity and other), dementia (cognitive symptoms, dementia in general, behavioural disorders and other), other and nothing. Three categories of best memories including role (fun-seeker, caregiver, reservoir of family wisdom and other), grandparent’s characteristics (e.g. kindness and compassion) and other |

| Creasey and Jarvis (1989) | USA | Quantitative descriptive study using a cross-sectional design | To explore whether burden mediates the relationship between GC’s relationship with their parents and GC’s relationship with their GP |

N = 29 GC. Age range: 8–18 years (M = 12.9, SD = 2.7) 7 of the GC were living with their GP, 22 lived nearby |

N = 29 GP with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Average duration of symptoms = 6 years No age or gender demographic information for grandparents |

The network of relationships inventory assessed GC’s perceptions of their relationships with mother, father and GP. Items scored on social provisions/support dimension, negative interactions dimension and overall satisfaction. Burden interview assessed mother and father burden | Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations | A trend was identified where GC reported less support, conflict and satisfaction in relationship with their GP, compared to relationship with parents. When mother burden was higher, GC were more likely to perceive less support and satisfaction in the relationship with their GP and their father and perceive a more conflicting relationship with their GP. High mother burden did not appear to affect relationship between GC and mother. No significant relationship between father burden and relationship with GP. |

| Creasey et al. (1989) | USA | Quantitative non-randomised case control design | To explore GC’s perceptions of their family environment, their GP and older adults in general, when their GP has a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease |

N = 29 GC with a GP with dementia. Age range: 8–18 years (M = 12.9, SD = 2.7) N = 29 GC with a healthy GP (no dementia). Age range: 8–18 years (M = 12.1, SD = 2.8) All lived within 20 miles of GP. |

N = 29 GP with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s type dementia. Age (M = 73.8, SD = 6.7). n = 29 GP did not have dementia, served as comparison group. Age (M = 66.6, SD =7.0). | Family environment scale assessed family relationships. Network of relationships inventory was used to assess quality of relationships and Kogan’s attitudes towards old people scale was used to identify GC’s attitudes to older people. Dementia rating scale measured cognition and behaviours of GP with dementia and burden interview assessed mother and father burden | Quantitative data were analysed using t tests, ANOVA, MANOVA and regression analyses | GC with a grandparent with dementia reported a poorer relationship than children with a healthy grandparent. No significant differences between two groups for perceptions of relationships with parents and attitudes towards older people. Mother burden was associated with predicted relationship affection, satisfaction and conflict between GC and GP. Lower father burden was associated with greater GC and GP conflict |

| Hamill (2012) | USA | Quantitative descriptive study using a cross-sectional design | To explore GC’s experiences of providing care to their GP with Alzheimer’s disease, including involvement in caregiving tasks and outcomes of caregiving | N = 29 GC with a GP with Alzheimer’s type dementia (21 women and 8 men). Age range: 11–21 years (M = 15.88, SD = 2.54). 29 mothers (M = 45.97, SD = 6.34) and 24 fathers (M = 49.04, SD = 7.9) also participated in interviews |

N = 29 GP with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s type dementia. Mean age = 79.29 years (SD = 8.28) 79.3% were grandmothers 20% of GP lived with GC, 44.8% in own home, 24.1% in nursing home and 10.3% in other accommodation |

Demographic questions, Parent objective and subjective burden were assessed using Zarit burden interview. Adapted penning activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) to assess GC’s objective burden. Affectual solidarity scale used to assess closeness between GC, parents and GP. Psychosocial maturity inventory used to assess social commitment and adapted version of attitude towards the provision of long-term care scale to assess willingness to provide care. Author composed item to assess GC’s willingness to provide care in future | Quantitative data analysed using Spearman’s rho correlations and Wilcoxon signed ranks test | GC are involved in providing support to their GP with dementia. The majority of GC had helped with an IADL in the past week, such as household chores and cooking. GC assisted with an average of 3.48 tasks (SD = 3.39). When GC’s parents provided more hours of support to GP, GC assisted with more IADLs. GC who reported greater affection for GP provided more assistance. Lower GC social responsibility was associated with GC’s father greater subjective burden. GC reported generally neutral attitude towards long-term care. GC who assisted with more tasks showed more positive attitudes towards long-term care. All GC reported that they would provide care to parents in the future, the majority as primary caregivers |

| Howard and Singleton (2001) | USA | Qualitative research design using interviews | To explore the impact a grandmother with dementia has on a granddaughter | N = 6 GC (all women). Age range: 21–27 years. Three participants were sisters and the other three participants not related |

N = 6 GP with a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s type dementia No further demographic information relating to GP. |

A semi-structured interview was developed. The authors wrote an interview guide with a series of open-ended questions to be used if GC appeared to experience difficulties expressing themselves. The interview guide was not provided | The data were analysed using thematic analysis | Themes included difficulties with social interaction and embarrassment in relation to their grandmother’s behaviour. Emotions such as guilt, sadness, frustration, anger and stress were described by GC. Themes were also identified regarding possessing information about dementia, engaging in activities and importance of social support |

| Huvent-Grelle et al. (2016) | France | Quantitative descriptive study using a cross-sectional design | To explore the burden experienced by GC who provided care for a GP with dementia |

N = 70 adult GC. Mean age = 38 years. Average of 2 young children and majority were women Three-quarters were employed. All GC had been providing care for 5 or more years |

N = 70 GP with a diagnosis of dementia. Mean age = 87 years All GP had at least 5 GC and the majority of GP were women | 55 questions to obtain demographic characteristics, information about types of support that GC provide to their GP and the presence of social, physical or mental health problems associated with their caregiving role | The quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics | The majority of GC reported that they were in good health and felt happy. All GC (100%) reported feeling helpful, 75.7% reported having a good quality of life. 27.1% of GC reported sleep difficulties and 10% reported taking medicine because of caregiving. 40% of GC reported feeling tired and depressed, 41.4% reported feeling lost and 45.7% reported feeling stressed. Many GC indicated that they wanted further support: 41.4% reported needing respite care, 57.1% reported needing support interventions and 51.4% reported needing financial help |

| Miron et al. (2019) | USA | Qualitative design using focus group interviews and questionnaires | To explore the GC’s concerns regarding interactions with GP with dementia and identify coping strategies used. To explore whether concerns and coping are related to solidarity and conflict motives |

N = 14 participated in focus group (12 women and 2 men) N = 8 completed questionnaires (6 women and 2 men). Mean age = 18.38 years (SD = 0.52) |

Focus group: N = 15 including 5 grandmothers, 6 grandfathers, 3 great-grandmothers and 1 great-grandfather. One GC had 2 grandparents with dementia Questionnaire: N = 8 including 1 grandmother, 3 grandfathers and 4 great-grandmothers |

Focus groups were conducted and an interview guide informed discussions. Topics included length of time since diagnosis, changes in GP, type of interactions, concerns about interacting with GP, desire to learn, ways to improve interactions and concerns about lacking skills to interact with GP. The questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions about topics of the focus groups | Data were analysed using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) | Results were considered in relation to a solidarity–conflict conceptual framework. GC expressed worries about being unable to maintain a relational connection with their GP, being unsure about how to interact with their GP and concerns about lacking perspective-taking skills and emotion regulation strategies. Coping strategies were guided by two interaction-related motives: maintaining solidarity and dealing with conflict. The authors explored self-focussed (problem-solving and emotion-focussed) and other focussed coping strategies |

| Szinovacz (2003) | USA | Qualitative research design using semi-structured interviews | To explore changes in relationship between GC and parent, and family dynamics when living with a GP with dementia | N = 17 GC (13 women and 4 men) age range: 12–19 years. Mean age = 15.18 years (SD = 2.19) |

N = 15 (11 women and 4 men). Mean age: 76.1 years (SD = 10.33) This included 8 grandmothers, 3 grandfathers, 1 step-grandmother, 1 great-grandmother, 1 father and 1 adoptive mother |

Semi-structured interviews with GC. Interviews explored how GC’s life had changed since the GP moved in or became unwell. Open-ended questions regarding changes in closeness to GP and changes to relationship with caregiver, and 10-point scale to assess perceived change. Questionnaires completed by GC’s caregiver to obtain demographic information, and to assess how care situation affected GC’s relationships, mood and behaviours, and changes to their own behaviours | Data were analysed using a grounded theory approach. Main trends were compared between two groups of care recipients (GP and parents) | Caring for GP had resulted in positive and negative changes to family relationships. GC noted respect for primary caregiver and improved relationship due to joint caregiving roles. GC described limitations to their family’s activities due to caregiving roles, stress in family relationships and caregivers’ increased focus on their GP. Comparison between GC and other caregivers demonstrated similar themes, such as difficulties due to GP’s behaviour and effects of caregiver’s stress on GC. |

| Werner and Lowenstein (2001) | Israel | Quantitative non-randomised case control design | To explore the meaning of grandparenthood for GC and GP where the GP has dementia, compared with GC and GP where the GP is healthy (no dementia) |

N = 12 GC with GP with dementia (7 women and 5 men). Mean age = 19.8 years N = 28 GC with GP without dementia (20 women and 8 men). Mean age = 22.4 years |

N = 12 GP with dementia (8 women and 4 men). Mean age = 81.3 years N = 28 GP without dementia (16 women and 12 men). Mean age = 78.7 years |

Demographic information, including number of GC and geographical distance. Grandparents’ role interview with GC and GP to assess meaning of grandparenthood. This provided scores for attitudinal, emotional, symbolic and behavioural domains. Quality of relationship assessed with a 4-point Likert scale | Quantitative data were analysed using Mann–Whitney U test and Pearson’s correlations | GC of a GP with dementia reported behavioural aspects of grandparenthood to be less important. Results did not demonstrate significant differences between groups on symbolic and emotional aspects. There was lower response concordance between GC and GP with dementia, than GC and GP without dementia. Geographical closeness was linked to the meaning of grandparenthood for GC and GP without dementia. In the dementia group, higher quality of relationship was linked to greater behavioural scores |

GC: grandchild; GP: grandparent.

Results

Study demographics

A summary of the general characteristics of the 12 reviewed studies is presented (Table 2). The studies were published between 1989 and 2019. Four studies adopted a qualitative design (Celdrán et al., 2014; Howard & Singleton, 2001; Miron et al., 2019; Szinovacz, 2003), two used a quantitative non-randomised design (Creasey et al., 1989; Werner & Lowenstein, 2001), three used a quantitative descriptive design (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Hamill, 2012; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016) and three adopted a mixed method design (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2011, 2012). Participants were recruited from Spain, United States of America (USA), France and Israel.

The sample size of quantitative studies varied from 29 to 70 participants, mixed method studies ranged from 138 to 145 participants and qualitative studies ranged from 6 to 145 participants. Most studies recruited a higher proportion of female participants, one qualitative study recruited only female participants (Howard & Singleton, 2001) and some studies did not provide gender details (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Creasey et al., 1989). Most studies recruited grandchildren who were either children or adolescents, whilst two studies recruited adult grandchildren (Howard & Singleton, 2001; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). Across the studies, researchers provided varied information about the ages of participants. Nine of the studies provided an age range of participants with grandchildren ranging from 8 to 27 years old. The remaining three studies provided a mean age of grandchildren ranging from 18.38 to 38 years (Werner & Lowenstein, 2001). Most of the studies did not explicitly state whether grandchildren were primary or auxiliary caregivers.

Results of the quality appraisal

Many of the studies met most of the quality criteria for the respective methodological design; however, there was some variation in quality (Table 1). For instance, quantitative studies provided insufficient information regarding the representativeness of participants or included participants who were not representative of the target population, such as studies that involved recruitment from day centres only. For some studies, minimal or no information was provided regarding non-response bias (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Hamill, 2012; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). Moreover, some quantitative studies used small samples and may have been underpowered (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Creasey et al., 1989; Hamill, 2012; Werner & Lowenstein, 2001). Furthermore, quality appraisal indicated that Huvent-Grelle et al. (2016) did not meet three of the criteria for descriptive studies.

The qualitative studies met most of the quality criteria. Nevertheless, a limitation of the qualitative study by Howard and Singleton (2001) was that three of six participants were sisters within the same family. Four of the 12 studies were conducted by the same authors, and the data were extracted from a larger research project using the same sample (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2011, 2012, 2014). These researchers predominantly used researcher-developed items, and the sentence completion items utilised by researchers limited the qualitative data gathered. Some studies did not provide a clear justification for why particular methodology was chosen. For instance, Hamill (2012) described their study aim to be to explore caregiving experience but adopted a quantitative study design and provided limited justification for this. Given the objectives of this study, a qualitative study may have been more appropriate.

Systematic review findings

Six themes were identified in line with the aim of the current review: role transitions; dementia-related changes to grandparent; adapting to the new relationship with grandparent; the multiplicity of impacts of caregiving; positive consequences of caregiving and personal gains; and influence of other family relationships.

Role transitions

Some studies highlighted transitions in the roles of both grandchildren and grandparents who had a diagnosis of dementia (Celdrán et al., 2011, 2012). Grandparents were often viewed as family members who would provide care for grandchildren during childhood (Celdrán et al., 2014). However, when their grandparent had been diagnosed with dementia, there may have been a shift in roles which led to grandchildren providing care for their grandparent. Some studies considered the roles and expectations of grandparenthood (Celdrán et al., 2014; Werner & Lowenstein, 2001). Werner and Lowenstein (2001) explored aspects of the grandparent role that were most important to grandchildren and their grandparents by comparing grandchild–grandparent dyads where grandparents did or did not have a diagnosis of dementia. Grandchildren with a grandparent with dementia indicated that behavioural aspects of grandparenthood were less important to them compared with grandchildren whose grandparents did not have dementia. Behavioural aspects related to activities that grandchildren expect to have with grandparents, such as talking, visiting them and helping with household tasks.

Grandchildren and their grandparents with dementia also indicated that attitudinal aspects of grandparenthood were less important when compared with satisfaction, symbolic and behavioural aspects of grandparenthood (Werner & Lowenstein, 2001). Attitudinal aspects were associated with the beliefs about the role of the grandparent to take care of grandchildren and play a part in their upbringing. These factors were not compared for the same grandchild–grandparent dyads before and after the onset of the dementia; therefore, it is not known whether important aspects of grandparenthood had changed following the onset of dementia. The authors identified that higher behavioural scores were associated with a higher quality relationship (Werner & Lowenstein, 2001). This suggests that activities and contact that grandchildren have with their grandparent with dementia may continue to influence their perception of the relationship. Moreover, some aspects of grandparenthood may not be consistent with the roles that a grandparent with dementia is able to take.

Some studies found that grandchildren cited their role of providing care to their grandparent as their responsibility and suggested a sense of reciprocity by acknowledging the care that their grandparents had provided to them during childhood (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012). In this way, grandchildren may view their role as giving back to their grandparent in a time of need. Grandchildren mentioned the roles that their grandparents had taken as some of their best memories of them (Celdrán et al., 2014). It was noted that grandparents’ multiple roles may include being a caregiver, fun-seeker and source of wisdom, thereby supporting the diversity of roles and the importance of the grandchild–grandparent relationship in some families. Werner and Lowenstein (2001) found low concordance between grandchild and grandparent scores on the different aspects of grandparenthood meaning, suggesting that they may hold different perceptions about the grandparent role. It is not known whether this difference in beliefs about the role was longstanding or dementia related.

Dementia-related changes to grandparent

Across studies, grandchildren reported varied changes to their grandparent, in terms of personality characteristics and behaviour. Some grandchildren reported negative changes, such as unpredictability and changes to their grandparent’s behaviours (Celdrán et al., 2014; Howard & Singleton, 2001; Szinovacz, 2003). These were associated with emotions such as guilt, frustration and sadness about the impact of dementia on their grandparent. Grandchildren highlighted how these uncharacteristic behaviours may not be understood by peers and can influence the interactions they have with their grandparent. Grandchildren expressed concerns that their grandparent may not remember them or their shared experiences anymore (Miron et al., 2019). Coping strategies for managing dementia-related changes included acceptance of behaviours and attempting to maintain the grandchild–grandparent relationship (Celdrán et al., 2009). Other grandchildren reported that positive qualities of their grandparent were still there but were displayed in different ways since the onset of dementia (Celdrán et al., 2014). Some grandchildren suggested that this was unexpected or that positive qualities were observed at times when their grandparent was less affected by dementia-related symptoms. The studies indicated that caregiving had helped grandchildren to develop an understanding of the variety of dementia-related symptoms and the progressive nature of dementia, particularly for grandchildren who lived with their grandparent (Celdrán et al., 2012).

Adapting to the new relationship with grandparent

In many studies, grandchildren described that there had been changes to their relationship with their grandparent and noted efforts to adapt to these changes (Celdrán et al., 2011, 2014; Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Creasey et al., 1989: Miron et al., 2019). Howard and Singleton (2001) highlighted that some grandchildren were worried about how to interact with their grandparent and sustain their changing relationship. Celdrán et al. (2011) identified differences among grandchildren regarding frequency of contact, emotional closeness and relationship satisfaction prior to the onset of dementia. This suggests that variation existed within the previous relationships that grandchildren had with their grandparent and thus may influence perceptions of changes to the relationship. Most grandchildren in this study reported that their overall relationship with their grandparent had not changed, despite reporting changes to aspects of their relationship (Celdrán et al., 2011). For instance, grandchildren described less contact, emotional closeness and satisfaction with the relationship when their grandparent had dementia. This was consistent with other studies where grandchildren reported poorer relationships with their grandparent with dementia (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Creasey et al., 1989). Generally, grandchildren who reported previous higher emotional closeness tended to note a greater deterioration to the relationship following the onset of dementia and attributed this change to dementia. In contrast, some grandchildren viewed changes to the relationship as positive, including increased closeness and shared activities (Celdrán et al., 2014).

Miron et al. (2019) explored how grandchildren may adjust to changes in the grandchild–grandparent relationship. The authors explored how grandchildren may adopt problem-focussed and emotion-focussed coping strategies such as planning conversation topics, including family members and avoiding potentially difficult situations. Other focussed strategies were also noted, including making their grandparent feel comfortable, avoiding difficult conversations and engaging grandparents in activities.

The multiplicity of impacts of caregiving

Several studies identified that grandchildren were involved in regular caregiving by assisting their grandparent with activities of daily living and described how caregiving had limited family and leisure activities (Celdrán et al., 2012; Hamill, 2012; Howard & Singleton, 2001; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016; Szinovacz, 2003). Grandchildren tended to provide more support when their parents provided more care to the grandparent and when they described higher affection for their grandparent (Hamill, 2012). This suggests that the previous grandchild–grandparent relationship may influence the future support they provide. Many grandchildren also described needing further support in the form of financial help, respite care or support interventions (Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016).

Some studies explored the emotional impact of caregiving (Celdrán et al., 2011; Howard & Singleton, 2001; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). Grandchildren tended to report that caregiving had a greater influence on their life when they were aware of the stress experienced by their grandparent’s primary caregiver, such as their parents or grandparent’s spouse (Celdrán et al., 2012; Szinovacz, 2003). Mixed emotions about caregiving were shared by grandchildren. Positive emotions are reported in the section below. Other grandchildren described experiencing negative emotions including loss, guilt, frustration, anger and embarrassment, often in relation to unpredictable and dementia-related behaviours (Celdrán et al., 2011; Howard & Singleton, 2001). Psychological distress was also explored by Huvent-Grelle et al. (2016); of those surveyed, 40% reported feeling depressed and 45.7% reported feeling stressed. Around one-quarter of grandchildren reported sleep difficulties and 10% reported taking medicine due to their caregiving role. This suggests that there may be implications for the physical and psychological health of grandchildren with a role as primary or auxiliary caregiver.

Positive consequences of caregiving and personal gains

Whilst multiple changes and demands associated with caregiving were reported, several studies also highlighted positive experiences and personal gains from caregiving (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012; Hamill, 2012; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). Many grandchildren described positive emotions associated with caregiving such as feeling satisfied, happy and reporting a good quality of life (Celdrán et al., 2011; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). Huvent-Grelle et al. (2016) found that 75.7% of the 70 grandchildren surveyed found caregiving to be rewarding. These positive emotions were reported by grandchildren who were primary or auxiliary caregivers. Nevertheless, the same studies found some grandchildren to describe difficulties with their role; thereby, indicating that variation exists between grandchildren.

Other studies noted that through caring for a grandparent with dementia, grandchildren had increased knowledge about dementia and had developed skills in caregiving-related tasks (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). These skills may be helpful if grandchildren provide care for other family members in future; indeed, grandchildren reported that they would provide future care to their parents if needed (Hamill, 2012). Some grandchildren mentioned that caregiving had enabled them to develop coping strategies to manage caregiving-related stress (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012). Grandchildren associated their caregiving role with increased maturity, responsibility and patience compared with peers, as well as more respect for older people and different values due to their caregiving experiences. Grandchildren also noted that caregiving had an influence on their attitude towards overcoming difficulties and making the most of life (Celdrán et al., 2009). Of note, these two studies utilised the same sample.

Influence of other family relationships

In some studies, the relationships that grandchildren had with other family members appeared to influence their experiences of providing care. For instance, the relationship between the grandchild and their parents or grandparent’s spouse (Celdrán et al., 2012; Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Creasey et al., 1989; Szinovacz, 2003). In some qualitative studies, themes were identified regarding the importance of family and social support, and the role that other family members can have on coping with the caregiving role (Celdrán et al., 2009; Howard & Singleton, 2001). It was suggested that grandchildren learnt coping strategies and ways to interact with their grandparent from their parents and grandparents’ spouses (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012). Many grandchildren described improvements in their relationship with the primary caregiver of their grandparent which they attributed to shared caregiving roles and improved communication. However, other studies found that caregiving may have a negative impact on family time and may place additional stress on family relationships (Celdrán et al., 2012; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016; Szinovacz, 2003).

Caregiver burden is a term used to describe carers’ perceptions of the physical, psychological, social and financial impacts of caregiving and caregiving-related activities (Etters et al., 2008). Several studies highlighted how burden or stress experienced by other family members may impact on grandchildren’s caregiving experiences and grandchild–grandparent relationships. In particular, studies have investigated how mother and father burden may influence the caregiving experiences of grandchildren (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Creasey et al., 1989). It was not stated in these studies whether grandchildren were primary or auxiliary caregivers; however, they were involved in providing care to their grandparent alongside their parents. Creasey and Jarvis (1989) suggested that parental burden may influence the grandchild’s perceptions of their grandparent if their parent has less time or attention due to caregiving responsibilities. Similarly, Szinovacz (2003) reported that some grandchildren had noticed that their parents’ caregiving responsibilities to their grandparent resulted in less focus on them. Parental burden may also provide an indication of the nature of caregiving-related tasks and the impact on the family system as a whole.

Creasey and Jarvis (1989) found that greater mother burden was associated with grandchildren perceiving less support and satisfaction in the grandchild–grandparent relationship and higher rates of conflict with their grandparent. The results for the influence of father burden were contradictory between studies; one study found no relationship between father burden and the grandchild–grandparent relationship (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989), another found that lower levels of father burden were associated with higher levels of grandchild–grandparent conflict (Creasey et al., 1989) and a further study identified that higher levels of father burden were reported when grandchildren reported lower social responsibility (Hamill, 2012). A commonality between the studies was the relatively small sample sizes and low statistical power; thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. Taken together, the results indicate variation in the extent to which other family relationships influence grandchildren’s perceptions of caregiving and the grandchild–grandparent relationship. However, the studies highlight the systemic nature of caregiving in the families studied, with other family members’ caregiving experiences influencing the grandchild–grandparent relationship.

Discussion

This review sought to explore the experiences of grandchildren who provide care to grandparents with dementia. There was a degree of variation in demographic characteristics of grandchildren in the included studies, including age, gender, country of origin and the extent of their caregiving role. Whilst some grandchildren were the primary caregiver, other grandchildren adopted an auxiliary caregiver role. Regardless of the role taken, many grandchildren described transitions in their role and relationships within the family, changes to their relationship with their grandparent, the multiple aspects of caregiving and positive aspects of caregiving. Transitions in roles and relationships have been explored in existing research with daughters providing care to their mothers (Donorfio & Kellett, 2006). This study did not focus exclusively on dementia, however, similar themes were found, including adapting to the caregiver role and acceptance of the new relationship. It is acknowledged that role transitions are not specific to grandchildren of a grandparent with dementia. It is likely that the roles that grandchildren take may change as a result of their grandparent ageing, regardless of health conditions. Nevertheless, it is possible that grandchildren’s experiences of this transition may differ if their grandparent is diagnosed with dementia compared to other health conditions or age-related changes.

Some grandchildren described a sense of responsibility or duty to give back to their grandparents following the onset of dementia. Previous research has explored societal norms regarding filial responsibility and reciprocity in relation to caring for older relatives (Gans & Silverstein, 2006; Wallhagen & Yamamoto-Mitani, 2006). Studies that have explored how relationship and cultural factors may influence filial responsibility have predominantly focussed on spousal and adult child caregivers (Quinn et al., 2010). Donorfio and Kellett (2006) suggested that there are different aspects of filial responsibility that may influence caregiving, including personal, family and spiritual beliefs. Notably, many of the included studies which explored this were conducted by the same authors using the same sample of grandchildren in Spain (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012). A focus for future research may, therefore, be to explore whether differences exist across samples from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Much of the previous research exploring the experiences of family caregiving in dementia has focussed on spousal and adult child caregivers. Grandchildren may be at a different life stage when they provide care to their grandparent with dementia, when compared with spouses and adult children (Dellmann-Jenkins et al., 2000). Across the included studies, some grandchildren were still in childhood, whilst others were in middle adulthood. This highlights that grandchildren are a heterogeneous group with different priorities, demands and roles. The variation in findings within individual studies suggests that the experiences of grandchildren may differ significantly. This has been noted by Fruhauf and Orel (2008) who found that the developmental level and context of caregiving influenced the ways that grandchildren coped with their caregiving role. Grandchildren may, therefore, experience unique challenges in integrating caregiving responsibilities with other aspects of their life, such as developing from a child into an adolescent or caring for their own children. Some grandchildren highlighted that they required more support with their caregiving role; however, it is not known whether the participants in this study were already in receipt of some support (Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016). Notably, this research recruited grandchildren who were the primary caregiver of their grandparent, rather than an auxiliary caregiver.

Whilst some grandchildren noted negative experiences of their caregiving roles and associated responsibilities, many grandchildren described positive aspects of caregiving. This is consistent with previous research regarding the positive experiences of providing care for a family member with dementia (Carbonneau et al., 2010; Doris et al., 2018). A recent review by Lloyd et al. (2016) identified similar positive elements of caregiving, including emotional rewards, development of personal traits and improvements to relationships and coping strategies. Another review suggested several domains of positive aspects of caregiving which relate to personal growth, the caregiving relationship and the wider family. The findings of the current review, therefore, highlight the positive elements of caregiving perceived by another group of family caregivers, the grandchildren of grandparents with dementia (Doris et al., 2018).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include that, to the author’s knowledge, it is the first systematic review investigating the experiences of grandchildren who care for a grandparent with a diagnosis of dementia. The protocol for this review was registered prospectively on PROSPERO. The current review also assimilated results from studies that utilised qualitative, quantitative and mixed methodologies to investigate the topic area. It is acknowledged that the themes were identified from the perspective of the researchers and different synthesis methods may have resulted in identification of different themes. A further limitation is that only studies published in English and in peer-reviewed journals were included which may have excluded potentially relevant results and, thereby, affected the conclusions drawn.

The reviewed studies varied in methodological design and participant demographics. Notably, grandchildren across the studies varied in age and life stage, and so may have different caregiving experiences. Many of the studies also did not explicitly state whether grandchildren were primary or auxiliary caregivers or included a mixed sample. Four studies utilised the same sample across studies as results were obtained for a larger project (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2011, 2012, 2014). The studies by Creasey et al. (1989) and Creasey and Jarvis (1989) also appeared to use the same sample recruited from a dementia service in the United States of America. This, therefore, reduces the diversity of the samples included in the current review. Furthermore, Howard and Singleton (2001) recruited three sisters from the same family for their qualitative study. Whilst there may have been similarities in their experiences, it is hypothesised that these grandchildren may still have experienced the caregiving role differently, and therefore, these results were suitable for inclusion in the current review.

The quality appraisal indicated that some quantitative studies provided insufficient information about the representativeness of participants and the subsequent ability to generalise findings (Celdran et al., 2009, 2011). The experiences of grandchildren who provide care to a grandparent who attends a day centre may be different to those who provide care to a grandparent who is in residential care, or who lives at home with their family. In this case, it is possible that grandchildren may adopt different caregiving roles and there may be variance in the grandchild’s involvement in their grandparent’s care. Consequently, the results of some of these studies may not be generalisable to grandchildren who provide care to their grandparent in other settings. Response bias is also important to consider in research involving caregivers as it may be that carers of people with dementia who are experiencing greater demands or stress are less likely to participate in research. Some studies provided minimal or no information regarding response bias (Creasey & Jarvis, 1989; Hamill, 2012; Huvent-Grelle et al., 2016); consequently, it is not possible to know whether the results represent the diversity of caregiving experiences and so whether the results could be generalised to a similar group. Some of the included studies used free text sentence completion items developed by the researchers, which required participants to provide the ending to a sentence (Celdrán et al., 2009, 2012, 2014). These types of question may have limited the qualitative information obtained from participants and so differ from other methods used in the other qualitative studies, such as interviews and focus groups which may have obtained richer and more detailed data. Whilst the study by Huvent-Grelle et al. (2016) did not meet three of the quality appraisal criteria for descriptive studies, it is acknowledged that less information may have been provided because it was submitted to the journal as a letter to the editor.

Furthermore, two of the studies that primarily involved grandchild–grandparent dyads also included several participants with different relationships, including step-grandparent and great-grandparent. The researchers contrasted the results for these relationships with grandchild–grandparent relationships and so this was accounted for when presenting results. Inclusion of these studies also ensured that relevant results for the review were not discounted. However, it is possible that grandchildren may have different relationships with great-grandparents and other relatives, compared with grandparents, and this may, therefore, have an influence on their experience of providing care for that family member. Roberto and Skoglund (1996) found that grandchildren associated their grandparents as having a greater influence on their lives and reported more frequent contact with their grandparents than with their great-grandparents. Therefore, whilst the current review combined results for grandparents and great-grandparents, it is acknowledged that there may be heterogeneity in results between these groups which may be further explored in future research.

Research implications

This review provides an overview of the current evidence base regarding the experiences of grandchildren who provide care for their grandparent with dementia. Notably, the qualitative elements of mixed method studies were limited. Future research may benefit from utilising qualitative methods such as interviews to gather richer data. Moreover, it would be important that future researchers account for the representativeness of samples and potential bias to recruitment methods. The sampling methods for some studies involved recruiting grandchild and grandparent dyads from nursing homes or day centres; it is possible that these grandchildren may experience their role differently due to the context of caregiving (Stephens et al., 1991). In addition, the low statistical power of studies may be addressed by researchers ensuring appropriate sample size calculations in future quantitative studies.

The reviewed studies were conducted in France, Israel, Spain and USA; therefore, there was some cultural diversity. It is acknowledged that there may be different stressors, expectations and sociocultural norms in relation to providing care for a relative with dementia across these countries. These may influence the roles that grandchildren take in their family, including a greater emphasis on kinship and filial responsibility in collectivist cultures (Lee et al., 1998; Quinn et al., 2010). Previous research has identified how cultural differences may affect perceptions of caregiving (Janevic & Connell, 2001). Moreover, differences in health and social care services may affect the care and support available. Of note, none of the studies were conducted in the United Kingdom. Consequently, it may be helpful for researchers to explore the caregiving experiences of grandchildren in different countries to elucidate similarities and differences across varied cultural, social and political contexts.

The studies placed little emphasis on the specific roles that grandchildren attributed to their grandparents prior to the onset of dementia, such as having a supportive or educative role. Grandchildren may perceive role transitions differently based on the prior role of their grandparent, the strength of the grandchild–grandparent relationship and the meaning that they attribute to the relationship (Werner & Lowenstein, 2001). Further research considering the previous grandchild–grandparent relationship and family roles in the context of current caregiving responsibilities may, therefore, be helpful. As there is likely to be variation in experiences, exploratory qualitative studies may provide an opportunity to gather rich data and inform future quantitative studies.

Clinical implications

This review highlights the influence of caregiving on grandchildren, whether they adopt a primary or secondary caregiving role. Research has documented the increasing prevalence of dementia and the growing numbers of family members adopting caregiving roles (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2015; Wittenberg et al., 2019). It is, therefore, important that the needs of grandchildren are acknowledged and assessed when they provide care for their grandparent, including considering the impact of caregiving on physical and psychological health. A thorough carers’ assessment of the roles and demands of grandchildren may assist with identification of appropriate support services and interventions. Group interventions may provide a cost-effective way to provide psychoeducation and support grandchildren to develop coping strategies to manage stress associated with their caregiving role. Group interventions may also provide an opportunity to signpost grandchildren to local services, enable grandchildren to learn from other people in similar situations and reflect on the positive and negative aspects of their caregiving role. As highlighted, grandchildren may have different experiences of caregiving due to their life stage and competing demands. In addition, secondary or auxiliary caregivers may be less able to access support from healthcare services. Therefore, providing group interventions which are tailored to the needs and roles of specific groups, such as grandchildren, may be helpful.

Conclusion

Research on the experiences of providing care for a family member with dementia has primarily focussed on spouse and adult child caregivers. Nevertheless, other family members at different life stages and with different roles may experience the caregiving role differently. Therefore, the current review sought to explore the experiences of grandchildren who provide care to their grandparent with dementia. The results identified a degree of variation in the demographics and caregiving roles of grandchildren, with some adopting a role as primary caregiver, and others adopting an auxiliary caregiver role. The findings indicate how providing care for a relative with dementia may impact multiple members of the system and can include positive and negative changes to roles and relationships. The review draws together the existing research about grandchildren as caregivers and helps to recognise the diversity in dementia caregiving. More systemic assessments and interventions may support the diversity of family members providing care and help family caregivers to continue this important role. Future research adopting qualitative designs may be helpful to obtain richer data regarding caregiving experiences of grandchildren, as well as expanding research to include participants from different cultural backgrounds.

Biography

Dr Sophie Venters is a Clinical Psychologist. She completed her doctoral training in Clinical Psychology at the University of Surrey. Her main research areas include dementia, the experiences of family caregivers, and coping strategies of caregivers of people with dementia.

Dr Christina J Jones is a Senior Lecturer in Clinical Psychology at the University of Surrey. Her main research areas are broadly in clinical health psychology and as such, focusses on the design and application of psychological interventions for individuals with physical and psychological difficulties. She also works closely with parents and caregivers and is interested in exploring and reducing the impact of long-term conditions on the family.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Sophie Venters https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2475-6008

References

- Alzheimer’s Research UK . (2015). Dementia in the family: The impact on carers. Retrieved January 7, 2020, fromhttps://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/about-us/our-influence/reports/carers-report/ [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H., Donkin M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217-228. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PmC3181916/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonneau H., Caron C., Desrosiers J. (2010). Development of a conceptual framework of positive aspects of caregiving in dementia. Dementia, 9(3), 327-353. DOI: 10.1177/1471301210375316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celdrán M., Triadó C., Villar F. (2009). Learning from the disease: Lessons drawn from adolescents having a grandparent suffering dementia. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 68(3), 243-259. DOI: 10.2190/AG.68.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celdrán M., Triadó C., Villar F. (2011). My grandparent has dementia: How adolescents perceive their relationship with grandparents with a cognitive impairment. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30(3), 332-352. DOI: 10.1177/0733464810368402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celdrán M., Villar F., Triadó C. (2012). When grandparents have dementia: Effects on their grandchildren’s family relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 33(9), 1218-1239. DOI: 10.1177/0192513X12443051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celdrán M., Villar F., Triadó C. (2014). Thinking about my grandparent: How dementia influences adolescent grandchildren’s perceptions of their grandparents. Journal of Aging Studies, 29(1), 1-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell N. L., Dujela C., Smith A. (2015). Caregiver well-being: Intersections of relationship and gender. Research on Aging, 37(6), 623-645. DOI: 10.1177/0164027514549258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G. L., Jarvis P. A. (1989). Grandparents with Alzheimer’s disease: Effects of parental burden on grandchildren. Family Therapy: The Journal of the California Graduate School of Family Psychology, 16(1), 79-85. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-37004-001 [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G. L., Myers B. J., Epperson M. J., Taylor J. (1989). Grandchildren of grandparents with Alzheimer’s disease: Perceptions of grandparent, family environment, and the elderly. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 35(2), 227-237. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23086366 [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G., Sancarlo D., Addante F., Ciccone F., Cascavilla L., Paris F., Picoco M., Nuzzaci C., Elia A. C., Greco A., Chiarini R., Panza F., Picoco M. (2015). Caregiver burden characterization in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(9), 891-899. DOI: 10.1002/gps.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellmann‐Jenkins M., Blank emeyer M., Pinkard O. (2000). Young adult children and grandchildren in primary caregiver roles to older relatives and their service needs. Family Relations, 49(2), 177-186. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00177.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donorfio L. K. M., Kellett K. (2006). Filial responsibility and transitions involved: A qualitative exploration of caregiving daughters and frail mothers. Journal of Adult Development, 13(3-4), 158-167. DOI: 10.1007/s10804-007-9025-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doris S. F., Cheng S. T., Wang J. (2018). Unravelling positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: An integrative review of research literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 79, 1-26. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etters L., Goodall D., Harrison B. E. (2008). Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20(8), 423-428. DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhauf C. A., Orel N. A. (2008). Developmental issues of grandchildren who provide care to grandparents. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 67(3), 209-230. DOI: 10.2190/AG.67.3.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans D., Silverstein M. (2006). Norms of filial responsibility for aging parents across time and generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4). 961-976. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00307.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilhooly K. J., Gilhooly M. L. M., Sullivan M. P., McIntyre A., Wilson L., Harding E., Woodbridge R., Crutch S. (2016). A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. Bio Med Central Geriatrics, 16(1), 106-114. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-016-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill S. B. (2012). Caring for grandparents with Alzheimer’s disease: Help from the “forgotten” generation. Journal of Family Issues, 33(9), 1195-1217. DOI: 10.1177/0192513X12444858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson L. G. (1992). Adult grandchildren and their grandparents: The enduring bond. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 34(3), 209-225. DOI: 10.2190/PU9M-96XD-CFYQ-A8UK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q. N., Pluye P., Fàbregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., Gagnon M. P., Griffiths F., Nicolau B., Rousseau M. C., Vedel I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. IC Canadian Intellectual Property Office. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMA T_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Howard K., Singleton J. F. (2001). The forgotten generation: The impact a grandmother with Alzheimer’s disease has on a granddaughter. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 25(2), 45-57. DOI: 10.1300/J016v25n02_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huvent-Grelle D., Boulanger E., Beuscart J. B., Delannoy L., Delabriere I., François V., Puisieux F. (2016). When French adult grandchildren become the primary caregivers of their grandparents with dementia: A desperate or an overlooked generation? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(9), 1920-1922. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.14328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janevic M. R., Connell C. M. (2001). Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in the dementia caregiving experience: Recent findings. The Gerontologist, 41(3), 334-347. DOI: 10.1093/geront/41.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Chang M., Rose K., Kim S. (2012). Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 846-855. DOI: 10.1111/j.13652648.2011.05787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Fontaine J., Read K., Brooker D., Evans S., Jutlla K. (2016). The experiences, needs and outcomes for carers of people with dementia: Literature review . RSAS. [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. R., Peek C. W., Coward R. T. (1998). Race differences in filial responsibility expectations among older parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 404-412. DOI: 10.2307/353857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J., Patterson T., Muers J. (2016). The positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: A critical review of the qualitative literature. Dementia, 15(6), 1534-1561. DOI: 10.1177/1471301214564792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Q., Liu S., Huo Y. R., Liu M., Liu S., Ji Y. (2015). Comprehensive analysis of patient and caregiver predictors for caregiver burden, anxiety and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(17), 2668-2678. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.12870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppa M., Luck T., Brähler E., König H.-H., Riedel-Heller S. G. (2008). Prediction of institutionalisation in dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 26(1), 65-78. DOI: 10.1159/000144027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe L., Ong B., Kinsella G. (2018). Mediators of burden and depression in dementia family caregivers: Kinship differences. Dementia, 1-17. DOI: 10.1177/1471301218819345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron A. M., Thompson A. E., McFadden S. H., Ebert A. R. (2019). Young adults' concerns and coping strategies related to their interactions with their grandparents and great-grandparents with dementia. Dementia, 18(3), 1025-1041. DOI: 10.1177/1471301217700965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Roberts H., Sowden A., Petticrew M., Arai L., Rodgers M., Britten N., Roen K., Duffy S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC methods programme. Retrieved January 7, 2020, from https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications.Php [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C., Clare L., Woods R. T. (2010). The impact of motivations and meanings on the wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 43-55. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610209990810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn C., Toms G. (2019). Influence of positive aspects of dementia caregiving on caregivers well-being: A systematic review. The Gerontologist, 59(5), 584-596. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gny168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raschick M., Ingersoll-Dayton B. (2004). The costs and rewards of caregiving among aging spouses and adult children. Family Relations, 533), 317-325. DOI: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.0008.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto K. A., Skoglund R. R. (1996). Interactions with grandparents and great-grandparents: A comparison of activities, influences, and relationships. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 43(2), 107-117. DOI: 10.2190/8F1D-9A4D-H0QY-W9DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto K. A., Stroes J. (1992). Grandchildren and grandparents: Roles, influences, and relationships. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 34(3), 227-239. DOI: 10.2190/8CW7-91WF-E5QC-5UFN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz S. A., Silverstein M. (2007). Relationships with grandparents and the emotional well-being of late adolescent and young adult grandchildren. Journal of Social Issues, 63(4), 793-808. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00537.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., Sherwood P. R. (2008). Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Journal of Social Work Education, 44(3), 105-113. DOI: 10.5175/JSWE.2008.773247702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C., Carter P. (2013). Mastery: A comparison of wife and daughter caregivers of a person with dementia. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 31(2), 113-120. DOI: 10.1177/0898010112473803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M. A. P., Kinney J. M., Ogrocki P. K. (1991). Stressors and well-being among caregivers to older adults with dementia: The in-home versus nursing home experience. The Gerontologist, 31(2), 217-223. DOI: 10.1093/geront/31.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz M. E. (2003). Caring for a demented relative at home: Effects on parent-adolescent relationships and family dynamics. Journal of Aging Studies, 17(4), 445-472. DOI: 10.1016/S0890-4065(03)00063-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Health and Social Care Information Centre. (2010). Survey of carers in households – England, 2009-10: Comparison results. Retrieved September 17, 2020, from https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/personal-social-services-survey-of-adult-carers/survey-of-carers-in-households-england-2009-10 [Google Scholar]