Abstract

Background

Communication with families is crucial in ICU care. However, only a few residency programs include communication and relationship training in their curricula. This study aimed to assess the impact of a communication-skill course on residents’ empathy and self-reported skills.

Material/Methods

A single-center, observational study was conducted. Since 2017, the 4th-year residents of the Anaesthesia and Intensive Care School, University of Milan attended the mandatory “Program to Enhance Relational and Communication Skills in ICU (PERCS-ICU)”. PERCS-ICU lasted 10 hours and involved small groups of residents. The course was articulated around the simulation and debriefing of 3 difficult conversations with trained actors. Before and after the course, residents completed the Jefferson Scale of Empathy and a questionnaire measuring self-assessed preparation, communication skills, relational skills, confidence, anxiety, emotional awareness, management of emotions, and self-reflection when conducting difficult conversations. The quality and usefulness of the course and the case scenario were assessed on a 5-point Likert scales.

Results

Between 2017 and 2019, 6 PERCS-ICU courses were offered to 71 residents, 69 of whom completed the questionnaires. After the course, residents reported improvements in empathy (p<.05), preparation (p<.001), communication skills (p<.005), confidence (p<.001), self-reflection (p<.001), and emotional awareness (p<.001). Residents perceived the course as very useful (mean=4.79) and high-quality (mean=4.58). The case scenario appeared very realistic (mean=4.83) and extremely useful (mean=4.91). All residents recommended the course to other colleagues.

Conclusions

PERCS-ICU proved to be a well-received and effective course to improve residents’ empathy and some self-reported skills. The long-term effects remain to be investigated.

Keywords: Critical Care; Empathy; Psychology, Clinical; Simulation Training

Background

Over the last 20 years, relational abilities have been increasingly recognized as pivotal skills in patient care. In the United States, communication skills have been included as core competencies that should be part of all graduate medical training programs by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Numerous studies have shown that empathic and effective communication is associated with increased patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment [1], better clinical outcome [2], and fewer malpractice claims [3]. Effective communication is associated with increased satisfaction with care and decreased bereavement burden of family members [4]. Empathy and relational abilities were also found to be beneficial for physicians, as they are associated with lower levels of burnout and greater satisfaction at work [5,6].

While communication skills are important in many clinical specialities, they are even more so when it comes to intensive care settings. Intensive Care Units (ICU) manage critically ill patients at risk of poor outcomes, including death. As ICU patients are often unconscious, clinicians have to master the relational and ethical complexity of communicating with the patient’s relatives. For clinicians working in the ICU, it is a common occurrence to engage with families in difficult conversations such as communicating bad news, sharing decisions about end-of-life care, notifying death, and exploring relatives’ attitudes to organ donation [7]. The physical isolation imposed by the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has highlighted how communicating with family members is a pivotal component of ICU care to the point that when it is prevented, creative ways have to be found to preserve the relationship with families [8].

Despite communication being recognized as a crucial skill for ICU clinicians [9], only a few international residency programs include communication training in their curricula [10,11]. To date, in Italy, communication skills are not part of the Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Residency programs. To address this educational need, in 2017 the Residency School of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care at the University of Milan introduced the “Program to Enhance Relational and Communication Skills for Intensive Care Unit” (PERCS-ICU) as a mandatory course for its 4th-year residents.

The aims of this study were: 1) to describe the implementation of a communication skills training program (PERCS-ICU) for ICU residents; and 2) to assess the effectiveness of the PERCS-ICU course.

Material and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a before-and-after, single-site, observational study. Participants were residents enrolled in the 4th year of the Residency School of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care at the University of Milan from 2017 to 2019. Participation in the PERCS-ICU course was mandatory. In 2020, PERCS-ICU was temporally suspended due to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak.

Intervention

The Program to Enhance Relational and Communication Skills (PERCS) is an established educational model that was developed at Boston Children’s Hospital-Harvard Medical School to teach communication and relational skills to postgraduate clinicians [12]. In 2008, the PERCS program was adapted to the Italian context and implemented at San Paolo University Hospital [13] and later at Humanitas Research Hospital [14]. Key features of the course are the use of experiential learning methods such as simulations and debriefings of case scenarios in a safe, collaborative, and interdisciplinary learning environment. Thanks to its flexibility, the PERCS model has been adapted to prepare practicing clinicians for a variety of challenging healthcare conversations such as communication of medical errors [15], communication regarding organ donation, and communication with dialysis patients [16]. In 2017, upon the request of the Scientific Board of the Residency School of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, University of Milan, a PERCS-ICU course for residents was implemented.

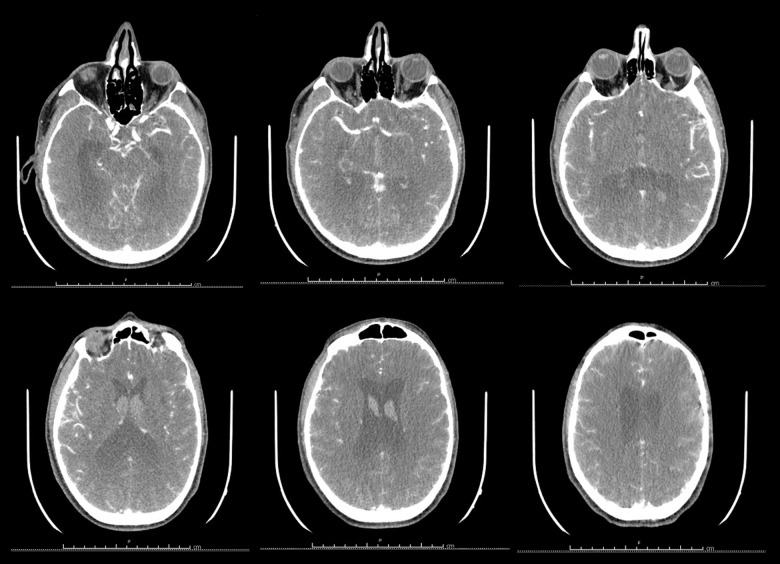

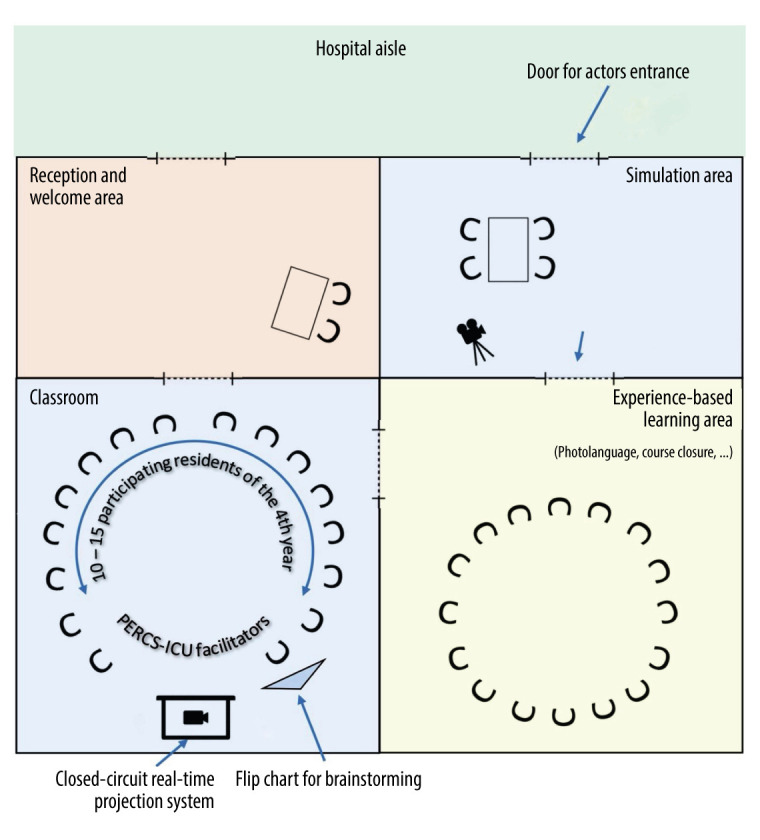

PERCS-ICU featured an 8-hour workshop (day 1) and a 2-hour follow-up (day 2) scheduled 15 days later. Two psychologists and an ICU physician trained in PERCS methodology facilitated PERCS-ICU. The workshop involved groups of 10–15 residents and was conducted using a combination of learning methods, such as lectures, simulations with trained actors, group debriefings, and a photolanguage session. The PERCS-ICU program is detailed in Table 1. Specifically, the workshop started with a brainstorming on what residents found effective when communicating difficult news to families. The workshop then expanded with a lecture on communication with families in the ICU to then proceed with the simulation of a case scenario in 3 conversations (Table 2). The first conversation regarded the communication of bad news to the wife upon the patient’s arrival in the ICU. The second conversation was about communicating treatment withdrawal to the patient’s wife and brother. The third conversation, conducted after the patient’s death, introduced the option of organ donation. The case scenario was inspired by a real case and was presented along with images to enhance the realism of the simulation (Figure 1). The complete case scenario, in Italian, is available upon request from the author. The conversations were conducted by 2 volunteer participants and trained actors, with a background in clinical psychology. The simulations were conducted in a separate room and were shown to all participants through closed-circuit television (Figure 2). A debriefing session with video review and actors’ feedback followed each simulation. The debriefings were facilitated using a learner-centered style. The facilitators started by asking the residents involved in the conversations how they felt and about their own experience. Then, the facilitators opened up the discussion to the actors and participants in order to share their feedback. Before the last simulation on organ donation, residents explored their emotions and attitudes to the topic through a photolanguage session [17]. Photolanguage is a structured group activity that uses a set of black and white photographs as the medium to stimulate communication on a topic. The two facilitators with a background in psychology conducted the photolanguage session. Finally, residents and facilitators shared a “take-home message” from the day of learning. At the end of day 1, residents were asked to apply some of the lessons learned during their everyday practice. During the follow-up sessions (day 2), residents recounted what they had applied and were able to discuss the challenges they had encountered with colleagues and facilitators.

Table 1.

Agenda of the PERCS-ICU course.

| Workshop (Day 1) | |

|---|---|

| 9.00–9.15 | Pre-questionnaires (Jefferson Scale of Empathy+self-reported questionnaire) |

| 9.15–9.30 | Participants and facilitators introduction |

| 9.30–10.00 | Brainstorming |

| 10.00–10.30 | Lecture: Communication with families in the ICU |

| 10.30–11.30 | Simulation (Communicating bad news); Group discussion |

| 11.30–11.45 | Break |

| 11.45–13.00 | Simulation (Communicating end of life); Group discussion |

| 13.00–14.00 | Lunch |

| 14.00–15.30 | Photolanguage; “Talking about organ donation with families” |

| 15.30–16.30 | Simulation (Organ donation request); Group discussion |

| 16.30–17.00 | Conclusions and task assignment for day 2 |

| Follow-up (Day 2) | |

| 16.00–16.45 | Experience sharing |

| 16.45–17.45 | Group discussion |

| 17.45–18.00 | Post-questionnaires (Jefferson Scale of Empathy+self-reported questionnaire) |

Table 2.

Case scenario portrayed during PERCS-ICU course.

|

Matteo Giannistrilvi is a 43-year-old artisan ice cream maker, married to Valeria, and with two daughters, aged 13 and 10. He started suffering slight and occasional headaches when he was 16, after a bad fall on his bike. A few days ago, he started complaining of a stronger headache. Last Tuesday, while he was in the back of his shop, he began to have a severe headache and suddenly started to vomit. His wife found him in the bathroom, sitting on the floor: he could not speak properly or move his right hand. In the sink, there were signs of vomiting and he could not explain what was happening. His wife called the medical emergency service right away. Once he arrived at the Hospital Emergency Room, Matteo was sedated and intubated. He was transported to the radiology department to perform a series of tests. The head CT scan with contrast medium showed dramatic bleeding, without any indication for neurosurgery. Matteo was then admitted to the intensive care unit to stabilize his respiratory and cardiovascular condition, which was also severely impaired Matteo’s neurological clinical condition was extremely severe: GCS=3, absence of all brain stem reflexes, except for the carenal reflex, preservation of spontaneous respiratory drive. First simulation The intensivist physician meets Matteo’s wife to present her with the dramatic clinical conditions (massive subarachnoid hemorrhage) and the prognosis (severe or very severe neurological disability, if he survives to the acute phase, and probable death). Second simulation In the subsequent days, the neurological condition evolves: the epileptic crises worsen and require use of high-dose sedatives (midazolam, propofol), in addition to antiepileptic drugs. Signs of cardiovascular dysautonomia (arterial hypertension, sinus bradycardia) appear. After 4 days of hospitalization, the two intensivist physicians on duty meet the patient’s wife, Valeria, together with the patient’s brother, Carlo, during the scheduled family meeting. They must present the decision-making process that led them to decide NOT to perform the tracheostomy, as the most clinically proportionate treatment for the patient. No recovery is now possible and the patient will likely die within the next hours/days. Third simulation The following day, a sudden neurological deterioration occurs: in the early hours of the night, Matteo loses his spontaneous respiratory drive. Various cardiovascular and hormonal signs of neurological dysautonomia gradually appear. The doctor on duty immediately suspends all sedatives in progress and thus the next morning the patient’s status is absence of all brain functions. An EEG is performed and the brain criteria for death are clinically verified. The Medical Direction is then activated, to set up the Commission to assess death by brain criteria. At the same time, someone calls the patient’s wife, asking her to come to the hospital because her husband is worsening. Upon arrival of the family members, about an hour after the neurological observation began (in Italy, the law requires two subsequent and full evaluations, six hours apart) Matteo’s death is notified to his wife and brother. Two hours from the beginning of the observation, the two intensivist physicians on duty meet the family members to explore their wishes regarding organ and tissue donation. |

Figure 1.

Head CT scan with contrast used in the scenario.

Figure 2.

Learning and simulation environment.

Data Collection

Before and immediately after the PERCS-ICU course, residents completed the Jefferson Scale of Empathy (JSE) for physicians [18] to measure empathy, and a questionnaire to assess self-reported skills in conducting difficult conversations.

The JSE is the most widely used scale in research to measure empathy among healthcare workers and has been translated into 56 languages. The JSE is composed of 20 items assessing empathy in the professional field. For each item, participants express their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Half of the items are reverse-scored. The total JSE score ranges from 20 to 140, with higher scores indicating greater levels of empathy.

A self-reported questionnaire developed by Meyer et al [19] was used to measure residents’ preparation, communication skills, relational skills, confidence, anxiety, emotional awareness, management of emotions, and self-reflection in conducting difficult conversations. The questionnaire was composed of 8 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

During the pre-course assessment, we also collected residents’ demographic data such as sex, age, nationality, years of experience, information about past training experience on communication, and the presence of a mentor.

During the post-course assessment, we included 5 additional questions inquiring about the usefulness and quality of the workshop, the realism and usefulness of the case scenario (5-point Likert scale), and the resident’s recommendation of the workshop to other colleagues (yes/no format).

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of San Paolo Hospital approved the study (registration number 2017/ST/185). All participants signed informed consent for their data to be published for research purposes.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, mean, SD) were used to report the residents’ demographic characteristics. To assess the normality of the distribution of all variables, skewness and kurtosis were examined. As the values of skewness and kurtosis ranged between.702 and −.889 for all variables, the scales were considered normally distributed. A paired-sample t test was used to assess differences in pre- and post-course measures of empathy, preparation, communication skills, relational skills, confidence, anxiety, emotional awareness, management of emotions, and self-reflection. All analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS Statistics 26). The statistical level was set at P<.05 (2-tailed tests).

Results

Between 2017 and 2019, 6 PERCS-ICU courses were offered, involving 71 residents. Of these, 69 completed the pre- and post-course questionnaires. Most residents (88%) were Italian, female (63%), with a mean age of 30.0 years (SD=1.01; range 29–33) and a mean of 4.4 years of experience (SD=0.55; range 4–6). Nearly half of them (47%) did not have a mentor in communicating with families and 15% did not have any previous training in communicating with patients and families. The demographic characteristics of residents are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of residents.

| Characteristics | N=69 |

|---|---|

| Sex – N (%) | |

| Female | 43 (63) |

|

| |

| Nationality – N (%) | |

| Italian | 61 (88) |

| Other | 8 (12) |

|

| |

| Age in years – mean (SD) | 30.0 (1.01) |

|

| |

| Years of experience – mean (SD) | 4.4 (.55) |

|

| |

| Presence of a mentor in communication – N (%) | |

| Yes | 36 (53) |

|

| |

| Past training experiences – N (%) | |

|

| |

| None | 9 (14) |

|

| |

| Exams | 5 (8) |

|

| |

| Pratical experiences | 8 (13) |

|

| |

| Internship | 18 (29) |

|

| |

| Other | 3 (5) |

|

| |

| Multiple of the above | 19 (31) |

After the PERCS-ICU course, residents reported improvements in empathy (P<.05), preparation (P<.001), communication skills (P<.005), relational skills (P<.05), confidence (P<.001), emotional awareness (P<.001) and self-reflection (P<.001). Differences between the pre-course and post-course measurements are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Differences between pre-course and post-course measurements.

| Dimension | Pre-course mean (SD) | Post-course mean (SD) | Student’s t | Cohen’s d | Confidence interval 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | |||||

| Empathy | 101 (20) | 104 (21) | −2.22* | −.29 | −4.84 | −.25 |

| Preparation | 2.3 (.66) | 3.1 (.68) | −7.68*** | −.93 | −1.01 | −.59 |

| Communication | 2.7 (.68) | 3.1 (.52) | −3.45** | −.42 | −.55 | −.14 |

| Relationship | 3.3 (.74) | 3.5 (.65) | −2.11* | −.25 | −.42 | −.01 |

| Confidence | 2.3 (.63) | 3.2 (.71) | −9.05*** | −1.09 | −1.05 | −.67 |

| Anxiety | 3.1 (.84) | 3.3 (.84) | −1.89 | −.23 | −.45 | .01 |

| Emotional awareness | 3.7 (.69) | 4.1 (.58) | −3.93*** | −.48 | −.55 | −.18 |

| Management of emotions | 3.29 (.77) | 3.4 (.70) | −1.46 | −.18 | −.41 | .06 |

| Self-reflection | 3.76 (.94) | 4.26 (.80) | −3.79*** | −.46 | −.76 | −.23 |

p<.05;

p<.005;

p<.001.

Residents rated the PERCS-ICU course as very useful (mean=4.79; SD=.61) and of high-quality (mean=4.57; SD=.55). The case scenario was perceived as very realistic (mean=4.83; SD=.38) and extremely useful (mean=4.91; SD=.28) for learning. All the residents (100%) stated that they would recommend the course to other colleagues.

Discussion

Clinician-family communication is an important component of the care of critically ill patients [7] and its role and function in the care process have become more evident since the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outbreak [20]. The literature shows that the quality of the clinician-family communication has a direct impact on family members’ satisfaction, decision-making, and mental health [4,21,22]. Within this context, PERCS-ICU proved to be an effective and feasible program for improving residents’ empathy and their perceived preparation, communication and relational skills, confidence, emotional awareness, and self-reflection when conducting difficult conversations. In contrast to other Italian PERCS workshops [14], PERCS-ICU for residents lasted longer and included a follow-up session. It is possible that the longer duration coupled with the integration of different learning methods, such as lectures, simulations, brainstorming, video reviews and photolanguage, contributed to the general effectiveness of the PERCS-ICU, thus allowing not only a perceived improvement in skills but also in attitudes such as empathy.

The increase in empathy is particularly relevant for clinical practice. Clinicians’ empathy was found to be associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients [2], greater satisfaction with ICU care in family members [22], and greater job satisfaction and diminished burnout in clinicians [23,24]. The empathy of medical students has been found to diminish over years of training on account of the “hidden curriculum”, namely, what is experienced and implicitly taught at medical school [25]. The results of this study show how a training program, such as PERCS-ICU, could counteract the effect of the “hidden curriculum” and cultivate empathy among residents.

After the PERCS-ICU course, residents reported a greater sense of preparation and confidence when conducting difficult conversations. They also reported an improvement in their communication and relational skills. The improvement of these aspects is particularly relevant for clinicians-in-training as it may promote a more positive attitude toward conversations with families and may help residents to face difficult conversations in the future, feeling better prepared and with greater confidence in themselves. After the PERCS-ICU course, residents also reported a perceived improvement in self-reflection and emotional awareness. Self-reflection is particularly important in medicine as it enables clinicians to clarify their own values and emotions, and how these may affect their clinical decisions [23]. Self-reflective capacity has been associated with a reduction in burnout and increased job satisfaction for physicians [5,6]. Increased self-reflective skills have been associated with improved professionalism, patient-centered care, and empathy [24, 25]. It is possible that the group debriefing questions, posed by the facilitators to help residents reflect on what happened in the conversation and how they felt, coupled with the video review of parts of the simulations and the photolanguage session, contributed to cultivating a self-reflective capacity and emotional awareness. Similarly, other learning experiences using narrative medicine showed that reflection increased self-awareness and recognition of one’s own and others’ emotions [26–30].

Interestingly, residents did not report a significant decrease in anxiety as in other PERCS programs [19]. According to the theory of processing efficiency, high or low levels of anxiety may compromise the performance of difficult tasks [26]. Conversely, a moderate level of anxiety can lead to increased activation and effort, thus improving work performance. We think that the presence of a moderate level of anxiety among residents at the idea of conducting difficult conversations may be functional and increase attention and performance.

The results of this study are consistent with those of other PERCS workshops developed for practicing clinicians, which reported an increase in perceived preparation, confidence, communication and relational skills after PERCS workshops [14]. Differently from other PERCS workshops, PERCS-ICU proved to also be effective in improving self-reflection and emotional awareness. This finding is particularly relevant considering that unlike other PERCS programs, which are attended on a voluntary basis, the PERCS-ICU course was mandatory. Despite the presence of residents with different levels of motivation, the course was perceived as very useful and high-quality and all residents stated they would recommend the course to other colleagues. The involvement of residents with different levels of motivation and attitudes toward communication supports the effectiveness of the findings and the efficacy of the PERCS-ICU course for adult learners.

Lastly, some limitations need to be acknowledged. The pre-post evaluation collected self-reported measures and not actual changes in behavior. The change in residents’ behavior after the course remains to be assessed as well as the impact of the training on family members’ outcomes. Moreover, despite the anonymity of the questionnaires, the involvement in the training of a faculty member of the residency school may have produced a social desirability effect in the resident’s responses. Lastly, the generalizability of the results is limited because the course involved only one residency school in Milan and it was not possible to include a control group.

Conclusions

The PERCS-ICU proved to be a feasible and effective course in improving not only residents’ perceived preparation, confidence, communication, and relational skills, but also empathy, self-reflection, and emotional awareness. Cultivating residents’ empathy, emotional awareness, and self-reflection during difficult conversations is particularly important as these capacities have been associated with improved satisfaction and mental health of family members and reduced burnout of residents.

Given the flexibility of the format and the limited resources employed, PERCS-ICU could be successfully implemented in other residency schools. In the future, PERCS-ICU could also be tailored to address specific communicative challenges that residents might encounter such as communicating with families using video or phone calls, which is becoming a necessary practice due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Future developments of the PERCS-ICU course regard the assessment of changes in residents’ behavior and family outcomes after the course, and the planning of follow-ups to consolidate learning.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniela Leone, Maria Luisa Vampa, and Stefano Pirovano for their contributions to the realization of the PERCS-ICU course. The authors would also like to thank the Council of the Residency School in Anesthesia and Intensive Care, University of Milan and the Professors Nino Stocchetti, Martin Langer and Antonio Pesenti, who requested and sustained the development of the residents’ course described in this article. This paper endorses the Humanization to Enhance Recovery On Intensive Care bundle (www.heroicbundle.org).

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material

Educational material is available upon authors’ request.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Financial support: This open access publication was supported by the University of Milan (grant # PSR2019_DIP_013_LAMIANI)

References

- 1.Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Canale S, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: An empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Acad Med. 2012;87:1243–49. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinson WDL, Roter JP, Mullooly VT, et al. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A Communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres OY, Aresté ME, Mora JRM, Soler-González J. Association between sick leave prescribing practices and physician burnout and empathy. PloS One. 2015;10:e0133379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302:1284–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134:835–43. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curley MAQ, Broden EG, Meyer EC. Alone, the hardest part. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1974–76. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langeron O, Monsel A. Communication with patients and relatives in ICU: A skill to master. Minerva Anestesiol. 2016;82:733–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markin A, Cabrera-Fernandez DF, Bajoka RM, et al. Impact of a simulation-based communication workshop on resident preparedness for end-of-life communication in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Res Pract Crit. 2015;2015:534879. doi: 10.1155/2015/534879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sullivan AM, Rock LK, Gadmer NM, et al. The impact of resident training on communication with families in the Intensive Care Unit. Resident and family outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:512–21. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-495OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browning DM, Meyer EC, Truog RD, Solomon MZ. Difficult conversations in health care: Cultivating relational learning to address the hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2007;82:905–913. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31812f77b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamiani G, Meyer EC, Leone D, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of an innovative approach to learning about difficult conversations in healthcare. Med Teach. 2011;33:e57–64. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.534207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borghi L, Meyer EC, Vegni E, et al. Twelve years of the Italian Program to Enhance Relational and Communication Skills (PERCS) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:439. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamiani G, Leone D, Vegni E. La comunicazione dell’errore in medicina: Valutazione di un’esperienza formativa. MEDIC. 2011;19:69–75. [in Italian] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamiani G, Gallieni M, Strada I, Vegni E. Le conversazioni difficili in nefrologia: Valutazione di un’esperienza formativa. Giornale Italiano di Nefrologia. 2013;30(3):1–9. [in Italian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bessell AG, Deese WB, Medina AL. Photolanguage: How a picture can inspire a thousand words. American Journal of Evaluation. 2007;28:558–69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Lillo M, Cicchetti A, Lo Scalzo A, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Preliminary psychometrics and group comparisons in Italian physicians. Acad Med. 2009;84:1198–202. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17b3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer EC, Sellers DE, Browning DM, et al. Difficult conversations: Improving communication skills and relational abilities in health care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:352–59. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181a3183a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mistraletti G, Gristina G, Mascarin S, et al. How to communicate with families living in complete isolation. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002633. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarzkopf D, Behrend S, Skupin I, et al. Family satisfaction in the intensive care unit: A quantitative and qualitative analysis Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1071–79. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bocci MG, D’Alò C, Barelli R, et al. Taking care of relationships in the Intensive Care Unit: Positive impact on family consent for organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:3245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brac Selph R, Shiang J, Engelberg R, et al. Empathy and life support decisions in Intensive Care Units. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1311–17. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamiani G, Dordoni P, Vegni E, Barajon I. Caring for critically ill patients: Clinicians’ empathy promotes job satisfaction and does not predict moral distress. Front Psychol. 2020;10:2902. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn Res. 2017;6:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: A longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84:1182–91. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plank M, Greenberg L. The reflective practitioner: Reaching for excellence in practice. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1546–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karnieli-Miller O, Michael K, Gothelf AB, et al. The associations between reflective ability and communication skills among medical students. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(1):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wald HS, Davis SW, Reis SP, et al. Reflecting on reflections: Enhancement of medical education curriculum with structured field notes and guided feedback. Acad Med. 2009;84:830–37. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a8592f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eysenck MW, Calvo MG. Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cogn Emot. 1992;6:409–34. [Google Scholar]