Abstract

Sodium butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, is predominantly produced by gut microbiota fermentation of dietary fiber and serves as an important neuromodulator in the central nervous system. Recent experimental evidence has suggested that sodium butyrate may be an endogenous ligand for two orphan G protein-coupled receptors, GPR41 and GP43, which regulate apoptosis and inflammation in ischemia-related pathologies, including stroke. In the present study, we evaluated the potential efficacy and mechanism of action of short-chain fatty acids in a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Fatty acids were intranasally administered 1 h post MCAO. Short-chain fatty acids, especially sodium butyrate, reduced infarct volume and improved neurological function at 24 and 72 h after MCAO. At 24 h, the effects of MCAO, increased apoptosis, were ameliorated after treatment with sodium butyrate, which increased the expressions of GPR41, PI3K and phosphorylated Akt. To confirm these mechanistic links and characterize the GPR active subunit, PC12 cells were subjected to oxygen–glucose deprivation and reoxygenation, and pharmacological and siRNA interventions were used to reverse efficacy. Taken together, intranasal administration of sodium butyrate activated PI3K/Akt via GPR41/Gβγ and attenuated neuronal apoptosis after MCAO.

Keywords: Short-chain fatty acid, butyrate, GPR41, PI3K/Akt, apoptosis, MCAO

Introduction

Stroke is the second most common cause of death and third leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 Ischemic stroke accounts for approximately 80% of all strokes,3 and ischemia-induced neuronal injury involves excitotoxicity, inflammation, Ca2+ overload, oxidative stress, free radicals, necrosis, and apoptosis.4–6 Although progress has been made in elucidating the pathophysiology of stroke, therapeutic interventions remain limited and novel approaches must be explored to mitigate the deleterious consequences of stroke. During ischemic stroke, lack of oxygen and glucose causes the depletion of ATP and subsequent cell injury and death.7,8 Since neurons have higher energy expenditures and lower energy reserves compared to other cell types, they remain the most vulnerable to ischemic injury;9 for this reason, neuronal apoptosis is the main etiological process and determinant for outcome in stroke.10,11

In the acute phase of stroke, neuronal apoptosis may be potentially reversible within the ischemic penumbra and, therefore, may be the next step in developing a treatment to improve neurological outcome. Recent studies on the interactions between the immune system and the gastrointestinal microbiota have emerged suggesting that targeting the microbiota may be important in regulating ischemic injury.12,13 More specifically, microbiota-derived metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which include acetate, butyrate, and propionate, play a central role in this gut–brain axis via regulation of lymphocyte populations.14 Although reported to be involved in nutrient and energy homeostasis, studies have now shown SCFAs to have novel functions as signaling ligands that regulate a variety of responses in the central nervous system.15 For example, in a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) mouse model, efficacy of sodium butyrate (NaB) was facilitated through the inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) and reduced expression of pro-inflammatory mediators.16 Probing upstream pathways, other studies have reported additional receptors mediating the effects of butyrate: GPR41 (also known as free fatty acid receptor 3, FFAR3) and GPR43 (or FFAR2)17–19; GPR41 is expressed on endothelial cells and enteric neurons,20,21 while GPR43 is expressed on adipocytes and immune cells.22 Convincingly establishing this upstream relationship between ligand and receptor in CHO cells, Wu et al.23 reported that butyrate activation of GPR41 regulated histone acetylation, proliferation, apoptosis, and cell-cycle progression. Although these findings validate mechanistic links, the intracellular pathway of butyrate affecting neuronal apoptosis in the pathophysiology of stroke remains unexplored.

To date, literature has shown that the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway is essential to cellular survival after ischemia/reperfusion,24 and in a bilateral common carotid artery occlusion mouse model, NaB was shown to attenuate apoptosis via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.25 Moreover, in LPS-induced MAC-T cells, NaB was shown to reduce both oxidative stress markers and apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt pathway.26 Taken together, we hypothesize that the effect of sodium butyrate on its downstream targets, GPR41/PI3K/Akt, may reduce neuronal apoptosis and neurological deficits in a rat model of MCAO.

Materials and methods

Animals’ model and experimental protocol

All experiments performed were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Loma Linda University and complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All experiments were reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments). A total of 272 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 250–300 g, were divided into either Sham (n = 41) or MCAO groups (n = 231), in a randomized fashion; and these experiments were performed in a blinded manner. Transient MCAO was induced as previously described.27 Briefly, rats were placed supine, a midline incision made in the neck, and the external carotid artery (ECA) and common carotid artery (CCA) were exposed. The ECA was ligated, and then the internal carotid artery (ICA) was isolated. A vessel clip was placed on the CCA and another on the ICA. Then a cut was made on the ECA, and a 4–0 silicon coated monofilament suture was inserted into the ECA. The vessel clip on the ICA was removed, and the suture advanced (18–22 mm) until resistance was felt. After 2 h of occlusion, the suture and CCA vessel clip were removed, and the ECA was closed. The neck wound was sutured closed, and the animal allowed to recover. All sham-operated animals survived, but the overall mortality for MCAO was 15.1% (35/231) (Supplemental Table 1). The experimental time-line is shown in Supplemental Figure 2.

Drug administration

Sodium acetate (Cat#S2889, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), NaB (Cat#B5887; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and sodium propionate (P1880/P5436, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Before administration, they were reconstituted in normal saline (NS). Sodium acetate (4.17 mg/kg, 12.5 mg/kg, 37.5 mg/kg), NaB (2.5 mg/kg, 7.5 mg/kg, 22.5 mg/kg), sodium propionate (1.25 mg/kg, 3.75 mg/kg, 11.25 mg/kg) or NS were intranasally administered at 1 h after MCAO. A total volume of 24 µL was delivered into left and right nares, alternating 6 µL at a time, every 5 min over a period of 20 min.

Intracerebroventricular injection

As described previously,28,29 rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (4% induction, 2.5% maintenance) and placed on a stereotaxic apparatus. The needle of a 10 µL Hamilton syringe was inserted through a burr hole using the following coordinates relative to the bregma: 1.5 mm posterior, 1.0 mm lateral, and 3.2 mm below the horizontal plane of the bregma. A total of 5 µL (500 pmol) GPR41 siRNA (Ca#S171937, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in sterile saline or scramble siRNA (Ca#4390843, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was injected at 24 h prior to MCAO surgeries as described previously.30 LY294002 (Cat#S1105, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), a specific PI3K inhibitor, was prepared at 50 mmol/L in DMSO31; 10 µL/l LY294002 or DMSO were infused 30 min before MCAO. Drugs or siRNAs were injected directly into the right lateral ventricle at a rate of 2 µL/min by a micro infusion pump. To prevent possible leakage, the needle was kept in for an additional 5 min after the injection and withdrawn slowly over 5 min. The burr hole was immediately sealed with bone wax after the needle was retracted. The incision was then sutured, and the rats were allowed to recover.

2,3,5-Triphenyltertrazolium chloride staining

The infarct volume was evaluated at 24 and 72 h after MCAO via TTC staining as previously described.32 The volumes of contralateral and non-infarcted tissue of the ipsilateral hemispheres were outlined and measured with ImageJ software (NIH). Due to the possible interference of brain edema on infarct volume, the following formula used was: Infract volume = ((volume of contralateral – volume of non-ischemic ipsilateral))/2*(volume of contralateral)*100%.33 Calculation of the infarct volume was performed in an unbiased, blinded fashion.

Short-term neurological function

Neurological function of rats was evaluated at 24 and 72 h after MCAO induction using both Modified Garcia and Beam balance tests as described previously.34 Neurological score was assessed by an observer who was blinded to the group assignments.

Assessment of long-term neurobehavior

The rotarod and foot fault tests were performed at four weeks post MCAO to assess sensorimotor coordination and balance as described previously.30 Morris water maze was performed from 22 to 26 days post-MCAO as previously described.35 For the cued test, the platform (diameter: 10 cm) was made visible, and the rats were guided to it. For the spatial test (block 1 to 4), the latency to find the submerged platform (1 cm below the water) was measured. For the probe test, the platform was removed, and the time spent in the platform quadrant was evaluated, which extended to a maximum of 60 s. Escape latency and swim path were recorded by a computerized tracking system (Noldus, Seattle, WA, USA).

Fluorescent immunostaining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on fixed frozen sections as previously described.29,33 Briefly, after brains were sliced into 10 µm thick coronal sections using a cryostat (CM3050S-3, Leica Microsystems, USA), the sectioned tissues were placed onto individual slides and dried at 37°C containers for at least 72 h before immunofluorescence staining. The slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 3 × 5 min and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. After being rinsed for another 3 × 5 min with PBS, the slides were blocked in 5% donkey serum for 1 h at room temperature. Brain sections were incubated with primary antibody, GPR41 (1:50; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), Cleaved Caspase 3 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), NeuN (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), GFAP (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and IBA1 (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were photographed and analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Fluoro-Jade C staining

As previously described, Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) staining was performed to evaluate degenerating neurons with a modified FJC ready-to-dilute staining kit (Biosensis, CA, USA) at 24 h after MCAO.31,35 FJC-positive neurons were counted in six sections per brain at ×200 magnification by an independent observer. Quantified analysis was performed with Image J software (ImageJ 1.4, NIH, USA). Data were expressed as the average number of FJC-positive neurons in the fields as cells/mm2.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling staining

To evaluate neuronal apoptosis, TUNEL staining was performed with an in situ apoptosis detection kit (Roche, Pleasanton, CA, USA) at 24 h post MCAO as previously described.36 Six arbitrary sections were taken from the peri-ischemic regions per brain using a 20× objective lens and then TUNEL-positive neurons and NeuN-stained positive cells (neurons) were individually counted. The data were presented as a ratio of TUNEL-positive neurons (%).

Western blotting

After TTC staining and imaging, brain slices were separated into the contralateral and ipsilateral hemispheres, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80°C. Western blot was performed as previously described.29,33 Primary antibodies used were rabbit polyclonal anti-GPR41 (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-PI3K (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphorylated-Akt (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Akt (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-C-Cas3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Cas3 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA). Goat polyclonal anti-actin and the secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The signals were visualized using an ECL Plus kit (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). Blot bands were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.4, NIH, USA). Results are expressed as relative density to actin and then normalized to the average value of the sham group.

Cell culture and treatment

PC12 cells from passages 6 through 9 were used. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% FBS, 10% HS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C as previously described.37 NaB was dissolved into PBS and diluted to different concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1, 5, 10 mmol/L) before the experiment. For treatment groups, cells were treated with NaB at 1 h after OGD/R. For siRNA or inhibitor groups, cells were pre-treated with GPR41 siRNA (100 nmol/L, Ca#S171937, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), NF023 (Specific Gβγ inhibitor, 10 µmol/L, Cat#1240, TOCRIS Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN, USA), Gallein (Specific Gα inhibitor, 10 µmol/L, Cat#3090, TOCRIS Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN, USA), LY294002 (10 µmol/L, Cat#S1105, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) at 24 h prior to OGD/R.

Oxygen–glucose deprivation/reoxygenation model

The oxygen–glucose deprivation/reoxygenation (OGD/R) model was performed in PC12 cells as described previously.37 Normal culture media was replaced with serum and glucose-free medium and then transferred into a gas-tight incubation chamber and flushed with 5% CO2/95% N2 gas. The inlet and outlet valves of the chamber were closed after 10 min of flush. The chamber was placed into a humidified atmosphere at 37°C for 6 h after OGD, and the cells were then subjected to reoxygenation with normal medium with in normoxic conditions (5% CO2) at 37°C for 24 h.

Protein extraction from PC-12 cells

Protein was extracted as previously described.37 Briefly, cells were harvested by scraping, rinsed with cold PBS, and homogenized with RIPA lysis buffer after respective treatments.

CCK-8 cell viability assay

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Japan) was used to assess cell viability with treatment after OGD/R. The PC12 cells were seeded in 96-well plates and subjected with different treatment as described previously. Cells were incubated with 10% CCK-8 solution for 2 h at 37°C according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then cell viability was determined by the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.38

Statistical analyses

All raw data were collected and analyzed by an investigator who was blinded to the group assignment. Data were presented as means and standard deviations. All tests were two-sided, and no further adjustment for multiple comparisons was done for the overall number of tests. Normal data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Non-parametric data were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc test. All statistical comparisons were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of short-chain fatty acid on brain infarction and neurobehavior after MCAO

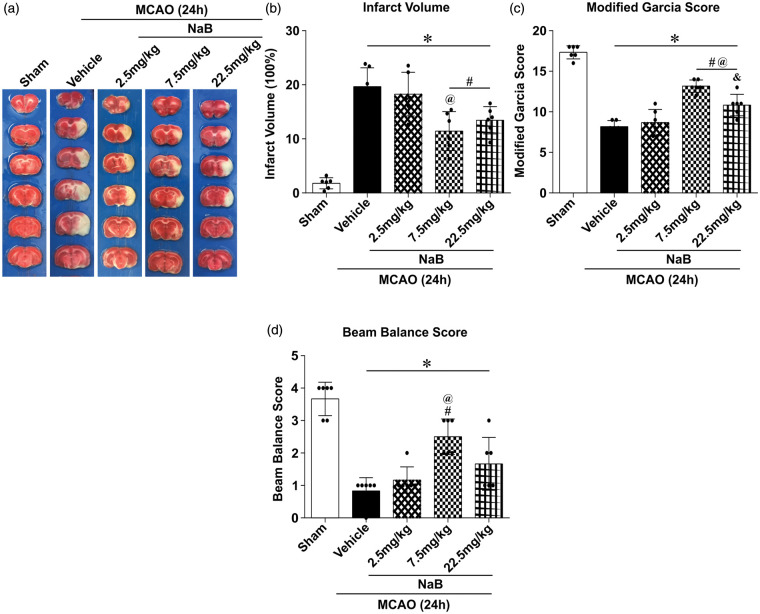

Compared to the vehicle group, TTC staining showed a significant reduction in the infarct volume in MCAO rats treated with either a middle (7.5 mg/kg, 11.43 ±3.60%) or high dose (22.5 mg/kg, 13.44 ± 2.52%) of NaB (19.66 ± 3.48%, p < 0.05; Figure 1(a) and (b)); no significant difference was observed in infarct volumes between vehicle and NaB low dose (2.5 mg/kg) groups (18.27 ± 4.04%, p < 0.05; Figure 1(a) and (b)). Congruently, no significant differences were observed in Modified Garcia and Beam Balance tests in the low-dose NaB group compared to the vehicle group (p < 0.05; Figure 1(c) and (d)). However, both the middle and high doses of NaB significantly improved neurological scores 24 h post-MCAO compared to the vehicle group (p < 0.05; Figure 1(c) and (d)). We chose the lowest working dose, the middle dose, for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Intranasal administration of NaB reduced infract volume and improved neurological deficits at 24 h after MCAO in rats. (a) Representative images of TTC-stained brain slices at 24 h after MCAO. (b) Quantified infarct volume, (c) Modified Garcia Score, and (d) Beam Balance Score showed NaB (medium (7.5 mg/kg) and high doses (22.5 mg/kg)) significantly decreased infarction and neurological deficits. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Sham, #p < 0.05 versus MCAO + Vehicle, @p < 0.05 versus MCAO + 2.5 mg/kg NaB, &p < 0.05 versus MCAO + 7.5 mg/kg NaB.

To determine if butyrate’s efficacy could be extended to other SCFAs, we investigated the effects of both acetate and propionate at 24 h after MCAO. In these SCFAs, only the middle-dose of sodium acetate (12.5 mg/kg) reduced infarction volume and improved function compared to the vehicle group at 24 h after MCAO. Neither the low nor high dose of sodium acetate, nor any other sodium propionate dose, significantly attenuated the deleterious outcomes associated with MCAO (Supplemental Figure 1).

Next, we explored if the effects of the NaB (7.5 mg/kg) could extend beyond 24 h. At 72 h post-MCAO, administration of NaB (7.5 mg/kg) reduced infarction volume and improved both behavior tests compared to the vehicle group (Supplemental Figure 1(c)).

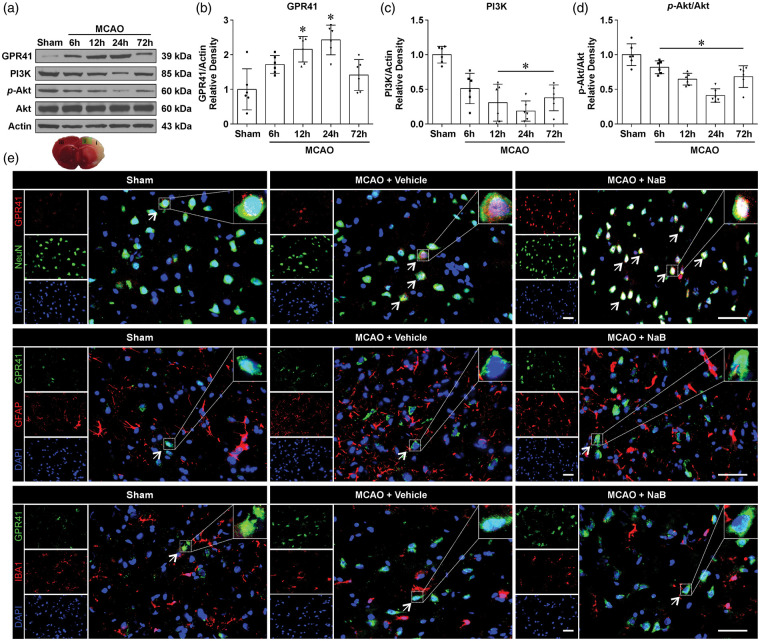

Expression of endogenous GPR41, PI3K, p-Akt and Akt after MCAO

In the brain tissue, Western blot was used to detect the temporal expression profile of GPR41 at baseline, 6, 12, 24, and 72 h after MCAO (Figure 2(a)). The endogenous expression of GPR41 showed a significant increase from 12 to 24 h after MCAO, but its expression returned to sham levels by 72 h (Figure 2(b)). PI3K and phosphorylated Akt were significantly decreased from 12 to 72 h after MCAO compared to the sham group (p < 0.05, Figure 2(c) and (d)). After NaB treatment (7.5 mg/kg), immunofluorescence staining revealed higher colocalization of GPR41 with neurons compared to both sham and MCAO + Vehicle groups; however, all groups demonstrated little to no colocalization of GPR41 with microglia and astrocytes (Figure 2(e)).

Figure 2.

Expression profiles of endogenous GPR41, PI3K, p-Akt and Akt after MCAO in rats. (a) Representative Western blot bands of time course and (b–d) quantitative analyses of endogenous GPR41, PI3K, p-Akt and Akt after MCAO. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group, *p < 0.05 versus Sham. (e) Double immunostaining of GPR41 with neurons (NeuN), astrocytes (GFAP) and microglia (IBA1) at 24 h after MCAO. Samples were obtained from ischemic penumbra 24 h following MCAO. White arrows indicate the cell shown in the higher magnification box or GPR41-positive neurons (Scale bar: 50 µm). n = 3 for each group.

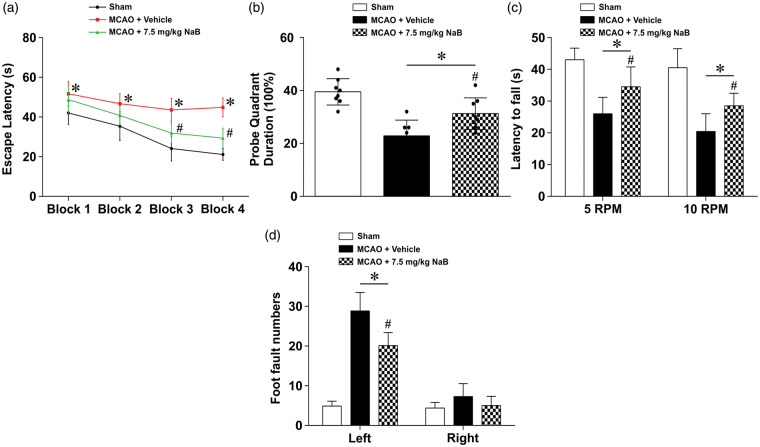

NaB improved long-term neurological function at four weeks after MCAO

To test the effects of NaB treatment on long-term neurological impairment caused by MCAO, neurological function was assessed by water maze, rotarod, and foot-fault tests at four weeks after MCAO. Vehicle-treated animals performed significantly worse compared to the sham group in the water maze escape latency and probe trial. NaB treatment significantly decreased the water maze escape latency in blocks 3–4 and increased the time spent in the platform quadrant during the probe trial compared to the vehicle group (p < 0.05, Figure 3(a) and (b)).

Figure 3.

NaB improved long-term neurological function at four weeks after MCAO in rats. (a) Treatment with NaB improved memory and learning abilities compared to the MCAO + Vehicle group as seen in a decreased escape latency, and an increased duration spent in the platform quadrant. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 8 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Sham, #p < 0.05 versus MCAO + Vehicle.

In the Rotarod test, animals in the vehicle group had a significantly shorter latency to fall in both 5 r/min and 10 r/min tests compared to the sham group (p < 0.05, Figure 3(c)). NaB treatment increased the latency at both 5 r/min and 10 r/min compared to the vehicle group. Evaluating ipsilateral deficits via foot-faults, the vehicle group had an increased number of faults compared to the sham group, whereas butyrate reversed these effects, reducing the number of faults compared to the vehicle group (p < 0.05, Figure 3(d)).

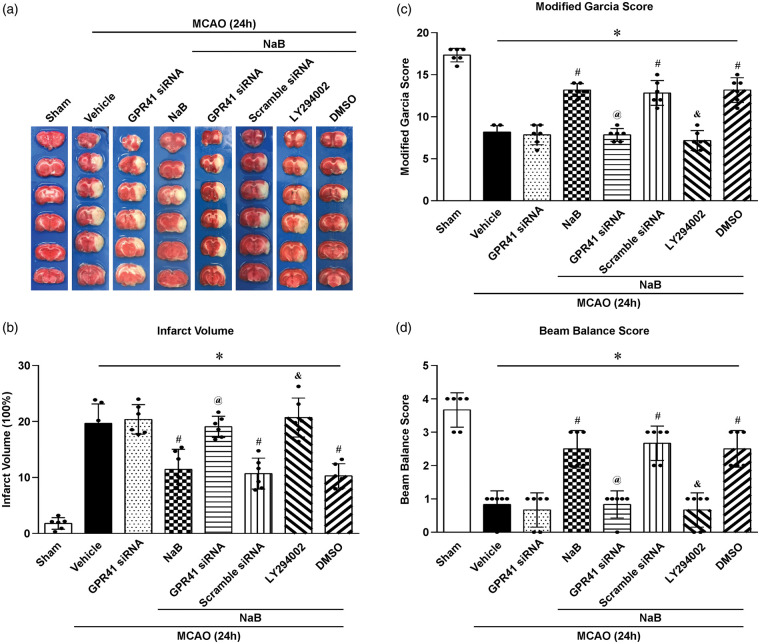

GPR41 siRNA and inhibition of PI3K abolished the therapeutic effects of NaB on neurological outcomes after MCAO

To elucidate the downstream molecular mechanisms of GPR41, two interventions were used: GPR41 siRNA and LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor). In the interventional groups, NaB efficacy was reversed, significantly increasing the infarction volume and neurological deficits compared to the NaB-treated group (p < 0.05, Figure 4(a) to (d)).

Figure 4.

Comparison of infarct volume and neurological scores after giving the GPR41 siRNA and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at 24 h after MCAO in rats. (a) Representative image of TTC-stained brain slices. (b) Infarct volume and (c) Modified Garcia Score and (d) Beam Balance Score showed that GPR41 siRNA and PI3K inhibitor LY294002 inhibited the neuroprotective properties of NaB, and there were no differences between these two inhibitor groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Sham, #p < 0.05 versus MCAO + Vehicle or MCAO + GPR41 siRNA, @p < 0.05 versus MCAO + NaB or MCAO + NaB+Scramble siRNA, &p < 0.05 versus MCAO + NaB or MCAO + NaB + DMSO.

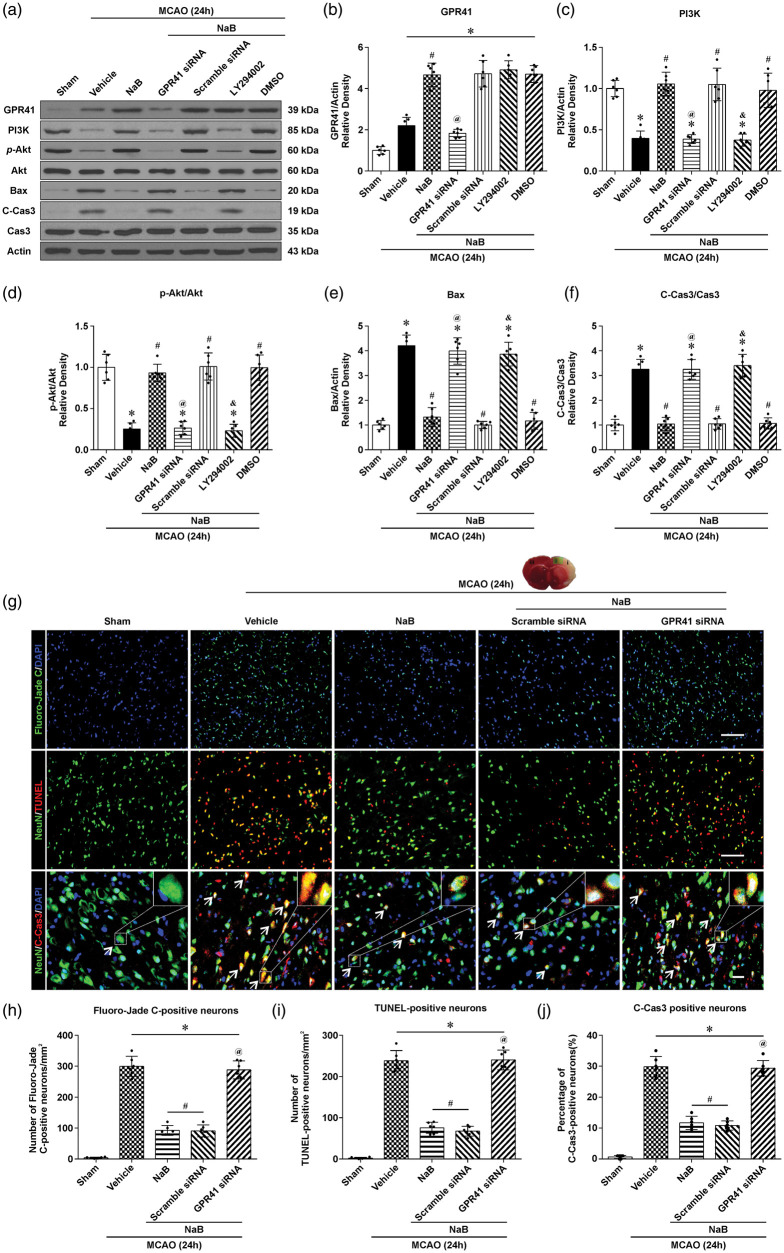

NaB attenuated neuronal apoptosis via GPR41/PI3K signaling pathway after MCAO

At 24 h, NaB significantly increased the protein expression of GPR41, PI3K and p-Akt, and decreased C-Cas3 and Bax compared to the vehicle. In the NaB+GPR41 siRNA group, GPR41, PI3K, and p-Akt expression were significantly decreased compared to NaB and NaB+scramble siRNA groups, whereas C-Cas and Bax were significantly increased (p < 0.05, Figure 5(a)). Furthermore, inhibition of PI3K with LY294002 decreased PI3K and p-Akt expression, while Bax and C-Cas3 were significantly increased compared to the NaB and scramble siRNA groups (Figure 5(c)).

Figure 5.

NaB attenuated neuronal apoptosis via the GPR41/PI3K signaling pathway at 24 h after MCAO. (a) Representative Western blot images and quantitative analyses of GPR41 (b), PI3K (c), p-Akt/Akt (d), Bax (e) and C-Cas3/Cas3 (f) after treatment with either NaB or NaB + GPR41 siRNA, NaB + Scramble siRNA, NaB + LY294002, NaB + DMSO. (g) Representative images of Fluoro-Jade C (green, upper line), terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL, red; NeuN, Green; middle line) and Cleaved Caspase3 (C-Cas3) (C-Cas3, red; NeuN, Green)-positive staining neurons in the ipsilateral cortex (Scale bar: 100 µm). (h–j) Quantification of Fluoro-Jade C, TUNEL and C-Cas3-positive neurons in the injured cortex. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Sham, #p < 0.05 versus MCAO + Vehicle, @p < 0.05 versus MCAO + NaB or MCAO + NaB+Scramble siRNA, &p < 0.05 versus MCAO + NaB or MCAO + NaB + DMSO.

Since MCAO injury results in caspase-mediated cell death and degeneration of neurons, brain coronal sections obtained at 24 h after MCAO were stained with Flouro-Jade C (FJC), TUNEL and Cleaved Caspase 3 (C-Cas3) to evaluate the efficacy of NaB. In the vehicle group, higher levels of FJC, TUNEL and C-Cas3-positive neurons were observed compared to the Sham group (Figure 5(g)). After treatment with NaB, FJC, TUNEL and C-Cas3-positive neurons were decreased compared to the vehicle (p < 0.05, Figure 5(h) to (j)). After siRNA inhibition of GPR41, increased FJC, TUNEL and C-Cas3-positive neurons were observed compared to NaB-treated animals.

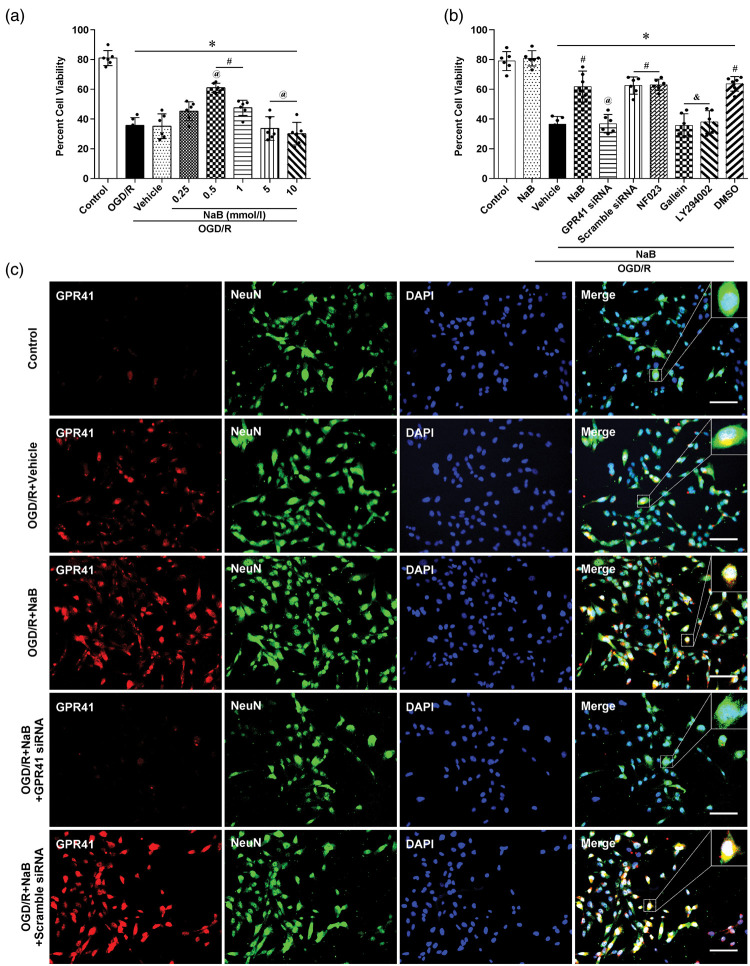

NaB attenuated OGD/R-induced oxidative injury via GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt in PC12 cells

Five dosages of NaB (0.25, 0.5, 1, 5 and 10 mmol/L) were used on PC12 cells at 1 h after OGD/R. Evaluating cell viability at 24 h after OGD/R, both 0.5 and 1 mmol/L NaB significantly improved outcome compared to PBS-treated cells (p < 0.05, Figure 6(a)). Therefore, the lowest working dose, 0.5 mmol/L, of NaB was used for the subsequent experiments.

Figure 6.

NaB attenuated OGD/R-induced oxidative injury via GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt pathway in PC12 cells. (a) Cell viability, measured by a CCK-8 assay, evaluated the efficacy of alternative NaB doses. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Control, #p < 0.05 versus OGD/R, @p < 0.05 versus OGD/R + vehicle or OGD/R + 0.25 mmol/L NaB. (b) Cell viability was used to evaluate downstream mechanisms with the following interventions: NaB, NaB + GPR41 siRNA, NaB + scramble siRNA, NaB + NF023, and NaB + Gallein, NaB + LY294002, NaB + DMSO. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Control or NaB, #p < 0.05 versus OGD/R + Vehicle, @p < 0.05 versus OGD/R + NaB or OGD/R + NaB + scramble siRNA, &p < 0.05 versus OGD/R + NaB or OGD/R + NaB + DMSO. (c) Immunofluorescence staining representative of GPR41 (red) and NeuN (Green) in PC12 cells, 24 h after OGD/R in Control, OGD/R + Vehicle, OGD/R + NaB, OGD/R + NaB + GPR41 siRNA and OGD/R + NaB+scramble siRNA groups (Scale bar: 50 µm).

To investigate the mechanistic impact of each specific G-protein subunit after NaB treatment, the following interventions were used: Control, NaB, OGD/R+Vehicle, OGD/R+NaB, OGD/R+NaB +GPR41 siRNA, OGD/R+NaB+scramble siRNA, OGD/R+NaB+NF023, OGD/R+NaB+Gallein, OGD/R+NaB+LY294002, OGD/R+NaB+DMSO. After NaB treatment, OGD/R-induced hypoxic injury was attenuated compared to the vehicle group; however, these protective effects were reversed by GPR41 siRNA, Gallein and LY294002 (p < 0.05, Figure 6(b)). Paralleling our in vivo data, PC12 cells confirmed immunoreactivity between NeuN and GPR41 after OGD/R (Figure 6(c)).

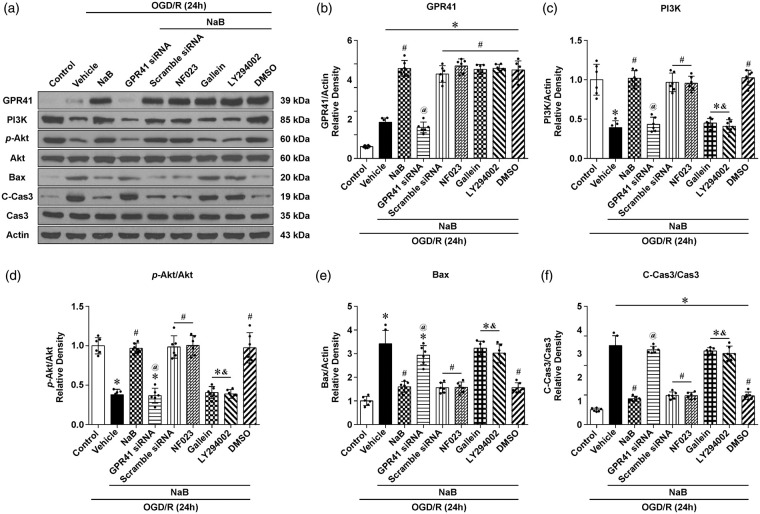

NaB-induced phosphorylation of Akt was dependent on the Gβγ subunit of GPR41 in vitro

In the OGD/R+NaB group, GPR41, PI3K, and p-Akt were significantly increased, while Bax and C-Cas3 were significantly decreased compared to the vehicle group. In the OGD/R+NaB+GPR41 siRNA group, GPR41, PI3K, and p-Akt were significantly decreased, while Bax and C-Cas3 were significantly increased compared to the NaB group (Figure 7(a) to (f)). In the OGD/R+NaB+Gallein (blocker of Gβγ(i/o)) group, p-Akt was significantly decreased, while Bax and C-Cas3 were increased compared to the NaB group (Figure 7(d) to (f)); however, NaB maintained efficacy with NF023, an inhibitor of the Gα(i/o) subunit, which confirmed the therapeutic dependency of NaB to the activation of the Gβγ subunit (Figure 7(a) to (f)).

Figure 7.

NaB-induced phosphorylation of Akt was dependent on the Gβγ Subunit of GPR41 in vitro. (a) Representative pictures of Western blot bands showing the expression of GPR41, PI3K, p-Akt/Akt, Bax and C-Cas3/Cas3 after treatment with NaB, NaB+GPR41 siRNA, NaB+Scramble siRNA, NaB+NF023 and NaB+Gallein, NaB+LY294002, NaB+DMSO. (b–f) Quantification of Western blot data. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 6 for each group. *p < 0.05 versus Control, #p < 0.05 versus OGD/R+Vehicle, @p < 0.05 versus OGD/R+NaB or OGD/R+NaB+scramble siRNA, &p < 0.05 versus OGD/R+NaB or OGD/R+NaB+DMSO.

Discussion

MCAO is a devastating event, and mounting evidence suggests that neuronal apoptosis contributes to the progression of ischemia-induced brain injury.29,39 In the present study, we used a MCAO rat model to explore the efficacy of SCFAs (acetate, butyrate, and propionate) and to elucidate the mechanistic pathways responsible for their effect. Compared to acetate and propionate, sodium butyrate (NaB) reduced infarct volume and improved short- and long-term neurological function after MCAO; NaB increased the expression of PI3K and promoted the phosphorylation of Akt via activation of GPR41, thereby reducing apoptosis. Immunohistochemistry confirmed that NaB reduced the numbers of degenerating and apoptotic neurons after MCAO. Following OGD/R in PC12 cells, GPR41 siRNA abolished the anti-apoptotic effects of NaB as demonstrated by an increase in degenerating and apoptotic neurons, and increased expression of pro-apoptotic markers C-Cas3 and Bax. To confirm the specific mechanistic links downstream of GPR41, Gallein, an inhibitor of Gβγ (Gi/o), or LY294002, an inhibitor of PI3K, was administered with NaB treatment; both interventions abolished the neuroprotective effects observed by NaB. These results confirmed our hypothesis that administration of NaB would activate the GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt pathway and reduce neuronal apoptosis post-ictus.

Studies from various fields of medicine have shown that the microbiota is a key determinant to outcome in many diseases, including those of the nervous system.40 In literature, bacterial translocation may decrease infarct size and neurological deficits after MCAO,41,42 and more recently, several lines of evidence suggest that brain function and behavior are significantly influenced by microbial metabolites.43,44 Therefore, SCFAs such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate are the most abundant products derived from commensal bacterial fermentation of indigestible dietary fibers in intestines.45 Out of these three SCFAs, butyrate shows the most promise as a neuroprotective therapy because of its pleiotropic impact on biological functions,46 ranging from increasing ATP production47 to activating the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR).19,48 Confirming the beneficial findings of others after ischemic injury,16,49,50 we found that NaB significantly decreased infarct volume and improved neurological outcome after ischemic stroke in rats, whereas acetate and propionate had no significant efficacy post-ictus.

NaB, the sodium salt form of butyrate, is commonly used in pharmacological studies and a well-known HDAC inhibitor, resulting in increased histone acetylation and pro-regenerative/pro-plasticity gene expression. In spite of the overwhelming use of butyrate as an HDAC inhibitor in ischemic stroke, studies have focused on anti-inflammatory outcomes after butyrate treatment, and its apoptotic endpoints have yet to be explored in the pathology of stroke.16,51

Of the two GPRs for SCFAs, GPR43 shows a higher affinity to the shorter aliphatic chains of acetate and propionate, whereas GPR41 preferentially binds propionate, butyrate, and valerate.17,52,53 Each GPR receptor has specific innate functions, e.g., GPR43 is significant in driving metabolic disorders, such as obesity and diabetes,54 whereas GPR41 can modulate neuronal activity and visceral reflexes via neuronal receptors.20 In our study, GPR41 levels were increased after MCAO in a time-dependent manner, and after NaB treatment, further increased to reach therapeutic levels. GPR41 siRNA reversed the neuroprotective effects from NaB treatment, increasing infarction volume and neurological deficits. Taken together, these findings indicate that NaB exerts efficacy in MCAO through the GPR41 receptor.

It is generally believed that neuronal apoptosis is a crucial process in determining functional outcome after ischemic stroke. Here we report that NaB attenuated neuronal apoptosis and improved functional outcome via the PI3K/Akt pathway. In agreement with our findings, in cerebral I/R injury models, studies have reported an increase in favorable outcome after NaB treatment reducing oxidative damage, inflammation, and apoptosis.25 To the best of our knowledge, although NaB is known to bind to GPR41, there is a dearth of information on the molecular pathway activated within neurons. However, the downstream molecular pathway of GPR41 has been well-characterized in stroke models. For example, in a MCAO mouse model, inhibition of myeloperoxidase, a pro-inflammatory enzyme, resulted in phosphorylation of Akt and decreased apoptotic markers.55 In addition, independent of apoptosis, flavonoid activation of Akt reduced circulating cytokines and improved outcome following focal ischemia in a mouse model.56 Paralleling these studies, in a traumatic brain injury mouse model devoid of acute cell death, necrostatin-1 treatment increased the phosphorylation of Akt and improved functional outcome, indicating a significant role of Akt in synaptic plasticity mechanisms following stroke.57 Thus, in the present studies, using inhibitors for both GPR41 and PI3K, we confirmed that NaB attenuated neuronal apoptosis following MCAO via the GPR41/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Furthermore, inhibiting the two functional subunits of GPR41, Gβγ(i/o) and Gα(i/o), we confirmed that NaB’s efficacy was dependent on the activation of the Gβγ subunit. Taken together, intranasal administration of NaB reduced neuronal apoptosis and neurological deficits via activation of the GPR41-Gβγ-P13K/Akt pathway.

In the present study, we found that a treatment dose of 0.5 mmol/l NaB significantly promoted cell survival in PC12 cells after OGD/R, but when doses were increased, NaB efficacy was ameliorated. Consistently, in a study evaluating the effects of butyrate on SH-SY5Y cells, pre-treatment dosages ranging from 25 to 100 µM showed protection against OGD, but this effect was reduced with higher butyrate concentrations.58 Although this report did not discuss this effect, we hypothesize that increased butyrate concentrations may reach cytotoxic levels and thereby activate apoptotic pathways. Along these lines, in a study on SAS cancer cells, higher treatment doses of butyrate, ranging from 4 to 16mM, resulted in increased ROS levels, reduced CDC 2 and cyclin b1, and increased apoptosis.59 Thus, we chose the 0.5 mmol/l NaB therapeutic dose for evaluation in this report.

In the canonical pathway, when ligands activate Gi-coupled GPCRs, the Gβγ subunits uncouple from Gi proteins and inhibit adenylyl cyclase, causing the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), phospholipase C-β (PLC-β), and protein kinase C (PKC).60–62 In high-fat diet-fed mice, literature has shown that the increased levels of SCFA, from the gut microbiota, activated GPCRs and attenuated insulin-mediated Akt phosphorylation in adipocytes.63 Paralleling these findings, Kimura et al.60 also reported that SCFAs and ketone bodies directly regulate the sympathetic nervous system activity via the GPR41-Gβγ-PLCβ-MAPK pathway. Exploring non-canonical downstream pathways, in human renal cortical epithelial cells, studies have shown that SCFA attenuated inflammation by activating GPR41/43 and subsequently inhibiting the phosphorylation of p38 and JNK; these results were confirmed by using a specific inhibitor for Gi/o-type G protein and Gβγ (i/o), both of which abrogated SCFA’s anti-inflammatory properties.64 Consistent with these findings, in OGD/R PC12 cells, the present study confirmed that administering Gallein, a small molecule inhibitor of Gβγ, abolished NaB’s efficacy, increasing the number of apoptotic cells; in detail, Gallein decreased both PI3K and p-Akt expression, while Bax and C-Cas3 were increased. To exclude alternative pathways, we also inhibited the second functional unit of GPR41, Gα, and no differences were observed in NaB’s efficacy following MCAO. These mechanistic studies support the link between Gβγ and cellular survival. Altogether, we are first to report the efficacy of NaB via the Gβγ subunit in stroke, and as pharmacological agents develop, future stroke studies may target this neuroprotective subunit.

In conclusion, intranasal administration of NaB significantly reduced infarct volume and improved short- and long-term neurological function in a rat MCAO model. For the first time in neurons, NaB was shown to activate the GPR41-Gβγ-P13K/Akt pathway and attenuate apoptosis. However, as a histone deacetylase inhibitor in neurons, immune cells and vascular cells, further research is needed to establish the epigenetic regulatory role of NaB. Nevertheless, these findings provide additional pharmacological targets and further the understanding of the pathology of strokes.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JCB910533 Supplemental Material1 for Sodium butyrate attenuated neuronal apoptosis via GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt pathway after MCAO in rats by Zhenhua Zhou, Ningbo Xu, Nathanael Matei, Devin W McBride, Yan Ding, Hui Liang, Jiping Tang and John H Zhang in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Supplemental material, JCB910533 Supplemental Material2 for Sodium butyrate attenuated neuronal apoptosis via GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt pathway after MCAO in rats by Zhenhua Zhou, Ningbo Xu, Nathanael Matei, Devin W McBride, Yan Ding, Hui Liang, Jiping Tang and John H Zhang in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Authors’ contributions: Zhenhua Zhou, Nathanael Matei, Devin W McBride, Yan Ding, Jiping Tang, John H Zhang conceived the research idea and experimental design. Zhenhua Zhou, Ningbo Xu, Hui Liang and Devin W McBride performed experiments. Zhenhua Zhou, Yan Ding and Ningbo Xu drafted the manuscript. Critical revisions of the manuscript were made by all authors. John H Zhang approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all the authors.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by an NIH grant (JHZ, NS081740) and supported by the National Science Foundation of China (No.81471194).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iDs

Zhenhua Zhou https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4548-4489

John H Zhang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4319-4285

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilgun-Sherki Y, Rosenbaum Z, Melamed E, et al. Antioxidant therapy in acute central nervous system injury: current state. Pharmacol Rev 2002; 54: 271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Candelario-Jalil E.Injury and repair mechanisms in ischemic stroke: considerations for the development of novel neurotherapeutics. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2009; 10: 644–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radak D, Katsiki N, Resanovic I, et al. Apoptosis and acute brain ischemia in ischemic stroke. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2017; 15: 115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon R, Meller R, Yang T, et al. Enhancing base excision repair of mitochondrial DNA to reduce ischemic injury following reperfusion. Transl Stroke Res 2019; 10: 664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klimova N, Long A, Kristian T.Significance of mitochondrial protein post-translational modifications in pathophysiology of brain injury. Transl Stroke Res 2018; 9: 223–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alaverdashvili M, Caine S, Li X, et al. Protein-energy malnutrition exacerbates stroke-induced forelimb abnormalities and dampens neuroinflammation. Transl Stroke Res 2018; 9: 622–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fricker M, Tolkovsky AM, Borutaite V, et al. Neuronal cell death. Physiol Rev 2018; 98: 813–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Xu N, Ding Y, et al. Chemerin reverses neurological impairments and ameliorates neuronal apoptosis through ChemR23/CAMKK2/AMPK pathway in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Cell Death Dis 2019; 10: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Tian J, Guo S, Chen H, et al. Combination of emricasan with ponatinib synergistically reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat brain through simultaneous prevention of apoptosis and necroptosis. Transl Stroke Res 2018; 9: 382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benakis C, Brea D, Caballero S, et al. Commensal microbiota affects ischemic stroke outcome by regulating intestinal gammadelta T cells. Nat Med 2016; 22: 516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Codagnone MG, Spichak S, O’Mahony SM, et al. Programming bugs: microbiota and the developmental origins of brain health and disease. Biol Psychiatry 2019; 85: 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marino E, Richards JL, McLeod KH, et al. Gut microbial metabolites limit the frequency of autoimmune T cells and protect against type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol 2017; 18: 552–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Q, Chen WD, Wang YD.Gut microbiota: an integral moderator in health and disease. Front Microbiol 2018; 9: 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patnala R, Arumugam TV, Gupta N, et al. HDAC inhibitor sodium butyrate-mediated epigenetic regulation enhances neuroprotective function of microglia during ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol 2017; 54: 6391–6411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 11312–11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, van Esch B, Henricks PAJ, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on lipopolysaccharide- or tumor necrosis factor alpha-stimulated endothelial cells via activation of GPR41/43 and inhibition of HDACs. Front Pharmacol 2018; 9: 533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun M, Wu W, Liu Z, et al. Microbiota metabolite short chain fatty acids, GPCR, and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol 2017; 52: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nohr MK, Egerod KL, Christiansen SH, et al. Expression of the short chain fatty acid receptor GPR41/FFAR3 in autonomic and somatic sensory ganglia. Neuroscience 2015; 290: 126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nohr MK, Pedersen MH, Gille A, et al. GPR41/FFAR3 and GPR43/FFAR2 as cosensors for short-chain fatty acids in enteroendocrine cells vs FFAR3 in enteric neurons and FFAR2 in enteric leukocytes. Endocrinology 2013; 154: 3552–3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolognini D, Tobin AB, Milligan G, et al. The pharmacology and function of receptors for short-chain fatty acids. Mol Pharmacol 2016; 89: 388–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J, Zhou Z, Hu Y, et al. Butyrate-induced GPR41 activation inhibits histone acetylation and cell growth. J Genet Genomics 2012; 39: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilic U, Caglayan AB, Beker MC, et al. Particular phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt on Thr308 via PDK-1 and PTEN mediates melatonin’s neuroprotective activity after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Redox Biol 2017; 12: 657–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun J, Wang F, Li H, et al. Neuroprotective effect of sodium butyrate against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 395895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Wang HH, Nie XT, et al. Sodium butyrate ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced cow mammary epithelial cells from oxidative stress damage and apoptosis. J Cell Biochem 2019; 120: 2370–2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo ZN, Xu L, Hu Q, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen preconditioning attenuates hemorrhagic transformation through reactive oxygen species/thioredoxin-interacting protein/nod-like receptor protein 3 pathway in hyperglycemic middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: e403–e411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Puri KD, Penninger JM, et al. Leukocyte PI3Kgamma and PI3Kdelta have temporally distinct roles for leukocyte recruitment in vivo. Blood 2007; 110: 1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matei N, Camara J, McBride D, et al. Intranasal wnt3a attenuates neuronal apoptosis through Frz1/PIWIL1a/FOXM1 pathway in MCAO rats. J Neurosci 2018; 38: 6787–6801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu G, McBride DW, Zhang JH.Axl activation attenuates neuroinflammation by inhibiting the TLR/TRAF/NF-kappaB pathway after MCAO in rats. Neurobiol Dis 2018; 110: 59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie Z, Enkhjargal B, Wu L, et al. Exendin-4 attenuates neuronal death via GLP-1R/PI3K/Akt pathway in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Neuropharmacology 2018; 128: 142–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Q, Manaenko A, Bian H, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen reduces infarction volume and hemorrhagic transformation through ATP/NAD(+)/Sirt1 pathway in hyperglycemic middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Stroke 2017; 48: 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu N, Zhang Y, Doycheva DM, et al. Adiponectin attenuates neuronal apoptosis induced by hypoxia-ischemia via the activation of AdipoR1/APPL1/LKB1/AMPK pathway in neonatal rats. Neuropharmacology 2018; 133: 415–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou K, Enkhjargal B, Xie Z, et al. Dihydrolipoic acid inhibits lysosomal rupture and NLRP3 through lysosome-associated membrane protein-1/calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii/tak1 pathways after subarachnoid hemorrhage in rat. Stroke 2018; 49: 175–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu J, Li X, Matei N, et al. Ezetimibe, a NPC1L1 inhibitor, attenuates neuronal apoptosis through AMPK dependent autophagy activation after MCAO in rats. Exp Neurol 2018; 307: 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang X, Hu Q, Li B, et al. Follistatin-like 1 attenuates apoptosis via disco-interacting protein 2 homolog A/Akt pathway after middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke 2014; 45: 3048–3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Souvenir R, Fathali N, Ostrowski RP, et al. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 mediates erythropoietin-induced neuroprotection in hypoxia ischemia. Neurobiol Dis 2011; 44: 28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu N, Liu B, Lian C, et al. Long noncoding RNA AC003092.1 promotes temozolomide chemosensitivity through miR-195/TFPI-2 signaling modulation in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis 2018; 9: 1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin Y, Zhang JC, Fu J, et al. Hyperforin attenuates brain damage induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rats via inhibition of TRPC6 channels degradation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, et al. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2010; 90: 859–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caso JR, Hurtado O, Pereira MP, et al. Colonic bacterial translocation as a possible factor in stress-worsening experimental stroke outcome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009; 296: R979–R985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tascilar N, Irkorucu O, Tascilar O, et al. Bacterial translocation in experimental stroke: what happens to the gut barrier? Bratisl Lek Listy 2010; 111: 194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun MF, Zhu YL, Zhou ZL, et al. Neuroprotective effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice: gut microbiota, glial reaction and TLR4/TNF-alpha signaling pathway. Brain Behav Immun 2018; 70: 48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez-Pardo P, Dodiya HB, Engen PA, et al. Role of TLR4 in the gut-brain axis in Parkinson’s disease: a translational study from men to mice. Gut 2019; 68: 829–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, et al. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016; 165: 1332–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cleophas MC, Crisan TO, Lemmers H, et al. Suppression of monosodium urate crystal-induced cytokine production by butyrate is mediated by the inhibition of class I histone deacetylases. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab 2011; 13: 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ang Z, Ding JL.GPR41 and GPR43 in obesity and inflammation – protective or causative? Front Immunol 2016; 7: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziemka-Nalecz M, Jaworska J, Sypecka J, et al. Sodium butyrate, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, exhibits neuroprotective/neurogenic effects in a rat model of neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Mol Neurobiol 2017; 54: 5300–5318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaworska J, Ziemka-Nalecz M, Sypecka J, et al. The potential neuroprotective role of a histone deacetylase inhibitor, sodium butyrate, after neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. J Neuroinflammation 2017; 14: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park MJ, Sohrabji F.The histone deacetylase inhibitor, sodium butyrate, exhibits neuroprotective effects for ischemic stroke in middle-aged female rats. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holsbeeks I, Lagatie O, Van Nuland A, et al. The eukaryotic plasma membrane as a nutrient-sensing device. Trends Biochem Sci 2004; 29: 556–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin HV, Frassetto A, Kowalik EJ, Jr., et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS One 2012; 7: e35240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi G, Sun C, Gu W, et al. Free fatty acid receptor 2, a candidate target for type 1 diabetes, induces cell apoptosis through ERK signaling. J Mol Endocrinol 2014; 53: 367–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HJ, Wei Y, Wojtkiewicz GR, et al. Reducing myeloperoxidase activity decreases inflammation and increases cellular protection in ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 1864–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clarkson AN, Boothman-Burrell L, Dosa Z, et al. The flavonoid, 2’-methoxy-6-methylflavone, affords neuroprotection following focal cerebral ischaemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 1266–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu X, Park J, Golinski J, et al. Role of Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin in functional outcome after concussive brain injury in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1531–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang RX, Lei J, Wang BD, et al. Pretreatment with sodium phenylbutyrate alleviates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by upregulating DJ-1 protein. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeng JH, Kuo MY, Lee PH, et al. Toxic and metabolic effect of sodium butyrate on SAS tongue cancer cells: role of cell cycle deregulation and redox changes. Toxicology 2006; 223: 235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura I, Inoue D, Maeda T, et al. Short-chain fatty acids and ketones directly regulate sympathetic nervous system via G protein-coupled receptor 41 (GPR41). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108: 8030–8035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi Y, Lai X, Ye L, et al. Activated niacin receptor HCA2 inhibits chemoattractant-mediated macrophage migration via Gbetagamma/PKC/ERK1/2 pathway and heterologous receptor desensitization. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 42279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khalil BD, Hsueh C, Cao Y, et al. GPCR signaling mediates tumor metastasis via PI3Kbeta. Cancer Res 2016; 76: 2944–2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kimura I, Ozawa K, Inoue D, et al. The gut microbiota suppresses insulin-mediated fat accumulation via the short-chain fatty acid receptor GPR43. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kobayashi M, Mikami D, Kimura H, et al. Short-chain fatty acids, GPR41 and GPR43 ligands, inhibit TNF-alpha-induced MCP-1 expression by modulating p38 and JNK signaling pathways in human renal cortical epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2017; 486: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JCB910533 Supplemental Material1 for Sodium butyrate attenuated neuronal apoptosis via GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt pathway after MCAO in rats by Zhenhua Zhou, Ningbo Xu, Nathanael Matei, Devin W McBride, Yan Ding, Hui Liang, Jiping Tang and John H Zhang in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Supplemental material, JCB910533 Supplemental Material2 for Sodium butyrate attenuated neuronal apoptosis via GPR41/Gβγ/PI3K/Akt pathway after MCAO in rats by Zhenhua Zhou, Ningbo Xu, Nathanael Matei, Devin W McBride, Yan Ding, Hui Liang, Jiping Tang and John H Zhang in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism