Abstract

Background:

In this era of effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) the incidence of AIDS defining cancers (ADCs) is projected to decline while the incidence of certain non-AIDS defining cancers (NADCs) increases. Some of these NADCs are potentially preventable with appropriate cancer screening.

Setting:

We examined cancer incidence, screening eligibility, and receipt of screening among persons actively enrolled in the DC Cohort, a longitudinal observational cohort of PLWH, between 2011-2017.

Methods:

Cancer screening eligibility was determined based on age, sex, smoking history and comorbidity data available and published national guidelines.

Results:

The incidence rate of NADCs was 12.1 (95% CI 10.7, 13.8) and ADCs 1.6 (95% CI 0.6, 4.6) per 1000 person-years. The most common incident NADCs were breast 2.6 (95% CI 0.5,1 2.1), prostate 2.3 (95% CI 1.2, 4.3), and non-melanoma skin 1.2 (95% CI 0.6, 2.3) incident diagnoses/cases per 1000 person-years. Among cohort sites where receipt of cancer screening was assessed, less than 60% of eligible participants had any ascertained anal HPV, breast, cervical, colorectal, hepatocellular carcinoma, or lung cancer screening.

Conclusions:

In this cohort of PLWH, there were more incident NADCs versus ADCs in contrast to earlier cohort studies where ADCs predominated. Despite a large eligible population there were low rates of screening. Implementation of cancer screening is an important component of care among PLWH.

Keywords: HIV, cancer, non-AIDS defining cancers, AIDS defining cancers, cancer screening, preventive care

Introduction

Mortality for persons living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has decreased with effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), and the life expectancy of those living with the virus is thought to approach that of the uninfected.(Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration, 2017; Porter et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2014) According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), persons over the age of 50 accounted for 47% of Americans living with HIV in 2015, and persons over the age of 50 accounted for 17% of the new HIV diagnoses in the United States (US) in 2016.(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017) Since HIV has become a chronic illness with expected long-term survival for those receiving appropriate therapy,(Marcus et al., 2016) recognition and management of common comorbid conditions including those associated with aging have become increasingly important.

In 2016, the leading causes of death in the US were heart disease, cancer, unintentional injuries, chronic lower respiratory diseases, and stroke.(Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E., 2017) Among persons living with HIV (PLWH), non-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) defining cancers (NADCs) have been reported as the cause of the largest number of deaths (15%) other than AIDS.(Smith et al., 2014) Cancers traditionally associated with HIV termed AIDS-defining cancers (ADCs), including Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), and invasive cervical cancer, are associated with co-infections with other viruses including Human Herpesvirus-8, Epstein Barr-Virus, and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV).(Riedel et al., 2015) NADCs are not directly associated with HIV infection, but studies suggest that PLWH may develop certain NADCs including those associated with non-HIV viruses more frequently than the general population. (Hernández-Ramírez et al., 2017)

Based on observed trends in the era of cART, NADCs are emerging as more likely to occur among PLWH than ADCs.(Yarchoan & Uldrick, 2018) Mathematical models project higher rates of NADCs, with lung and prostate cancers being the most common cancer types, among PLWH by 2030.(Shiels et al., 2018) With this expected shift in cancer etiologies and increased risk for certain cancers among PLWH, targeted age and/or disease appropriate cancer screening is important.(Aberg et al., 2014) Cancer related deaths and morbidity are potentially preventable with effective screening leading to early diagnosis and treatment.

Our aims were to describe both the incidence of specific NADCs and ADCs in a cohort of persons receiving care for HIV in the District of Columbia (DC) and to determine cancer screening practices in this cohort. Assessment of both cancer incidence and cancer screening performance can help inform targeted screening implementation and guide strategies for risk factor modification.

Methods

Study Population:

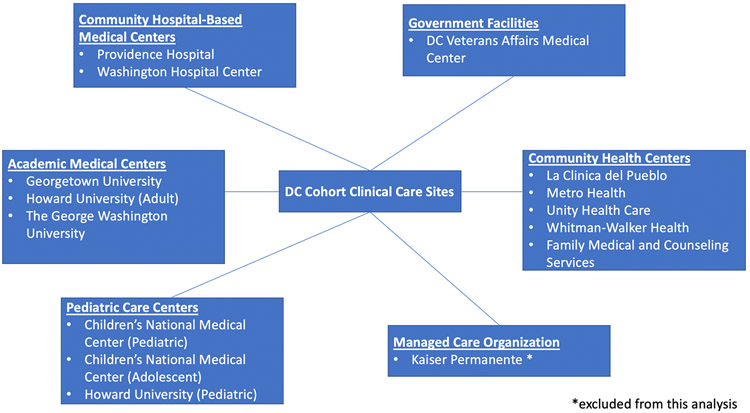

This analysis was conducted using data from the DC Cohort, a longitudinal observational cohort of PLWH receiving care in one of fourteen medical sites in DC. The clinical sites of care are outlined in FIGURE 1 and consist of academic medical centers, community hospital based medical centers, government facilities, community clinic health centers, pediatric care facilities, and managed care organizations. The study design and methodology have been described previously.(Greenberg et al., 2016) Clinical, laboratory, and sociodemographic data for consenting participants were routinely extracted from electronic medical records (EMR) to the DC Cohort database. At enrollment certain diagnoses including cancer and cirrhosis of the liver were entered manually by a research team member.

FIGURE 1:

DC COHORT STUDY SITES

Data collected between January 2011- December 2017 were included in this analysis. We included adult participants (age ≥18) enrolled at 14 of the 15 DC Cohort clinical sites who contributed ≥3 months of active follow-up. The start of follow-up was defined as 3 months after enrollment to allow for sufficient time for baseline cancer diagnoses to be abstracted. The end of follow-up was defined as the day prior to inactive status, six months after the participant’s last HIV RNA, or December 31, 2017, whichever was earliest.

Cancer Screening Eligibility and Receipt of Screening:

Eligibility for cancer related screening and criteria for ascertainment of receipt of screening is outlined in TABLE 1. We used recommendations from the primary care guidelines for the management of PLWH from the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) to approximate screening eligibility and receipt of screening for breast cancer, cervical cancer, and anal HPV using available data points. Recommendations from the US preventive services task force (USPSTF) for eligibility and receipt of screening were similarly employed for colorectal and lung cancer, and guidelines from the American Associated for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) were used for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).(US Preventive Services Task Force et …; Moyer and U.S. Preventive Services Ta…; Terrault et al. 2018; Heimbach et al. 2018) Participants with a known history of cancer and those with incident cancers during the follow-up period were excluded.

TABLE 1:

CANCER SCREENING ELIGIBILITY AND SCREENING RECEIPT CRITERIA

| CANCER | SCREENING ELIGIBLE*** | SCREENING RECEIPT CRITERIA*** |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | Female sex at birth without a history of breast cancer* and ≥50 years of age | Mammogram**** |

| Cervical | Female sex at birth and no history of cervical cancer* | Cervical pap***** |

| Colorectal | 55 to 80 years of age and no history of colorectal cancer* | Colonoscopy**** Sigmoidoscopy**** Fecal Occult Blood Testing**** Colon biopsy**** |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) | Chronic hepatitis b infection* with cirrhosis*, black or Asian male sex at birth ≥ 40 years of age, or female sex at birth ≥ 50 years of age and no history of HCC* OR Chronic hepatitis c infection* with cirrhosis* and no history of HCC* |

Abdominal Ultrasound**** |

| Human Papillomavirus (HPV)/Anal | Men who have sex with men (MSM) mode of HIV transmission and no history of anal cancer* OR Female sex at birth with a history of abnormal cervical Pap or diagnosis of genital warts* and no history of anal cancer* (History of anal receptive intercourse as a factor for anal HPV screening as recommended by the IDSA could not be ascertained using available data and was not used for this analysis.11) |

Anal Pap***** |

| Lung | Current smoker** 50 to 75 years of age with no history of lung cancer* (Total pack years of smoking as a factor for lung cancer screening as recommended by the USPSTF could not be ascertained using available data.14) |

Computerized tomography of chest**** |

Defined based on ICD-9/10 coding

Defined based on chart review of smoking history at enrollment, diagnosis codes for nicotine or tobacco dependence, and/or prescriptions for smoking cessation medications

We used recommendations the IDSA to approximate screening eligibility and receipt of screening for breast cancer, cervical cancer, and anal HPV using available data points in DC Cohort database as outlined in the methodology. Similarly, recommendations from the USPSTF were used to approximate screening eligibility and receipt of screening for colorectal and lung cancer. Recommendations from AASLD were used to approximate screening eligibility and receipt of screening for HCC

Determined based on CPT coding

Determined based on pathology reports

Eligibility for cancer screening was calculated among fourteen cohort clinical sites. Analysis of cancer screening receipt was limited to the six hospital-based sites and additional analysis was done to ascertain receipt of cancer screening among participants who received primary care services at their DC Cohort enrollment site. The rationale was that the hospital-based sites would capture the performance of cancer screening procedures such as colonoscopy and/or imaging completed within the same health system as the HIV clinic visits. Community-based sites did not perform these procedures therefore they would not be captured in the EMR via Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) coding. The additional determination of cancer screening receipt among participants who received primary care services at their DC Cohort enrollment site was completed as a sensitivity analysis.

Statistical Methods:

Participant characteristics were described using frequencies and percentages or medians and interquartile ranges as of the end of active follow-up. We assessed differences in categorical and continuous variables by whether patients had a history of cancer using the Chi-square testing (or Monte Carlo estimation of exact p-values when cell counts had expected values <5) and Kruskal-Wallis tests. For those comparisons, cancer type was classified as none, NADC, or ADC (participants with an NADC and ADC were classified in the ADC category).

Incidence for each cancer type was calculated among participants at risk by dividing the number of new incident cases by the total person-time at risk during the observation period, starting at 3 months after the date of enrollment/consent throughout the end of active follow-up, as defined above. 95% confidence intervals were calculated using quasi-likelihood Poisson regression, which included a dispersion parameter to account for overdispersion.

Predictors of NADCs and ADCs diagnoses were assessed. Covariates included HIV RNA, CD4+ T lymphocyte count, nadir CD4+ T lymphocyte count, time since HIV diagnosis, age, sex at birth, race/ethnicity, and viral co-infection. Diagnoses were determined through International Classification of Diseases (ICD) - 9/10 codes. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to obtain unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for covariates of interest. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, mode of HIV transmission, nadir CD4+ T lymphocyte count, baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count, baseline HIV viral load (VL), time since HIV diagnosis, tobacco use, substance use, and insurance status were included in the multivariable model. For multivariable regression modeling, missing data that were multiply imputed (five times) using the discriminant function method for race/ethnicity (2.4%), mode of HIV transmission (17.7%), insurance status (5.2%), employment (34.7%), nadir CD4 count (<0.1%), recent CD4 count (0.8%), and recent HIV VL (0.7%).(Yuan, 2011) Parameter estimates were pooled across each imputed data set using Rubin’s rules. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Cohort Characteristics:

TABLE 2 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the cohort participants both with and without cancers. Among the 7912 participants in this analysis, the median age was 50 years, 72.4% (n=5729) were male and 77.8% (n=6152) non-Hispanic black. The most common mode of HIV transmission was MSM at 38% (n=3006). The median time since HIV diagnosis was 13.2 years, and the median time of DC Cohort follow-up was 3.4 years. The most recent median CD4+ T cell count was 1232 cells/μL and 15.6% (n=1232) of the participants had a VL ≥200 copies/mL at the most recent testing. Substance use disorder was noted in 13.5% (n=1060), 3.3% (n=264) had HBV, and 12.7% (n=1003) had HCV. The majority of (69.8%) participants had government insurance.

TABLE 2:

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DC COHORT PARTICIPANTS JANUARY 2017 TO DECEMBER 2017

| Total sample (n=7,912) |

No cancer (n=7,206) | AIDS-Defining Cancer* (n=202) |

Non-AIDS Defining Cancer (n=504) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (col %) | n (col %) | n (col %) | p | |

| Years of DC Cohort follow-up, median (IQR) | 3.4 (1.9, 5.2) | 3.4 (1.8, 5.1) | 3.9 (2.2, 5.6) | 4.4 (2.6, 6.0) | <0.0001 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 50 (39-58) | 49 (39-57) | 52 (43-60) | 60 (52-66) | <0.0001 |

| Male sex at birth | 5,729 (72.4) | 5,162 (71.6) | 171 (84.7) | 396 (78.6) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6,152 (77.8) | 5,645 (78.3) | 135 (66.8) | 372 (73.8) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 996 (12.6) | 852 (11.8) | 42 (20.8) | 102 (20.2) | |

| Hispanic | 432 (5.5) | 403 (5.6) | 15 (7.4) | 14 (2.8) | |

| Other | 146 (1.8) | 134 (1.9) | 6 (3.0) | 6 (1.2) | |

| Unknown | 186 (2.4) | 172 (2.4) | 4 (2.0) | 10 (2.0) | |

| Mode of HIV transmission | <0.0001 | ||||

| MSM | 3,006 (38.0) | 2,700 (37.5) | 114 (56.4) | 192 (38.1) | |

| Heterosexual | 2,598 (32.8) | 2,407 (33.4) | 38 (18.8) | 153 (30.4) | |

| IDU | 534 (6.7) | 460 (6.4) | 12 (5.9) | 62 (12.3) | |

| MSM + IDU | 72 (0.9) | 65 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.4) | |

| Other | 309 (3.9) | 287 (4.0) | 8 (4.0) | 14 (2.8) | |

| Unknown | 1,393 (17.6) | 1,287 (17.9) | 30 (14.9) | 76 (15.1) | |

| Insurance status | 0.0028 | ||||

| Public | 5,526 (69.8) | 5,005 (69.5) | 133 (65.8) | 388 (77.0) | |

| Private | 2,037 (25.7) | 1,868 (25.9) | 62 (30.7) | 107 (21.2) | |

| No known insurance | 190 (2.4) | 183 (2.5) | 4 (2.0) | 3 (0.6) | |

| Unknown | 159 (2.0) | 150 (2.1) | 3 (1.5) | 6 (1.2) | |

| Employment | <0.0001 | ||||

| Employed | 2,383 (30.1) | 2,177 (30.2) | 72 (35.6) | 134 (26.6) | |

| Unemployed | 2,496 (31.5) | 2,298 (31.9) | 48 (23.8) | 150 (29.8) | |

| Other ** | 610 (7.7) | 497 (6.9) | 27 (13.4) | 86 (17.1) | |

| Unknown | 2,423 (30.6) | 2,234 (31.0) | 55 (27.2) | 134 (26.6) | |

| History of substance abuse | 1,060 (13.4) | 951 (13.2) | 25 (12.4) | 84 (16.7) | 0.079 |

| History of smoking | 4,442 (56.1) | 3,998 (55.5) | 112 (55.5) | 332 (65.9) | <0.0001 |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (years), median (IQR) | 13.2 (7.6-20.5) | 12.5 (7.4-20.1) | 16.6 (9.8-23.0) | 17.7 (10.9-24.5) | <0.0001 |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/μL), median (IQR) | 262 (107-418) | 271 (113-427) | 128.5 (43-277) | 186.5 (74.5-324) | <0.0001 |

| Recent CD4 count (cells/μL), median (IQR) | 592 (390-809.5) | 603 (401-818) | 425.5 (287-698) | 480.5 (288-692) | <0.0001 |

| Recent HIV viral load ≥200 copies/mL | 1,232 (15.6) | 1,151 (16.0) | 29 (14.4) | 52 (10.3) | 0.0029 |

| Chronic Hepatitis B infection | 264 (3.3) | 222 (3.1) | 16 (7.9) | 26 (5.2) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic Hepatitis C infection | 1,003 (12.7) | 877 (12.2) | 26 (12.9) | 100 (19.8) | <0.0001 |

Table 2: Participants who were diagnosed with both an ADC and NADC were classified in the ADC category. Of the 202 with an ADC 42 (20.8%) also had a NADC.

Includes retired, student, disabled, or other

Participants with an ADCs had a median age of 52 years versus 60 for those with NADCs and 49 for those without cancer (p<0.0001). Across all groups the majority of participants were non-Hispanic black: no cancer 78.3% (n=5645), ADC 66.8% (n=135) and NADC 73.8% (n=372). The most common mode of HIV transmission across all groups was MSM: no cancer 37.5% (n=2700), ADC 56.4% (n=114) and NADC 38.1% (n=192). Participants without a cancer diagnosis had a nadir CD4 + T lymphocyte count of 271 cells/μL (113-427), ADC 129 (43-277), and NADC 187 (75-324) (p<0.0001).

Cancer Incidence:

As described in TABLE 3, the incidence rate of NADCs was 12.1 (95% CI 10.7,13.8) and ADCs 1.6 (95% CI 0.6,4.6) per 1000 person-years. The most common incident NADCs were breast 2.6 (95% CI 0.5,12.1), prostate 2.3 (95% CI 1.2,4.3), non-melanoma skin 1.2 (95% CI 0.6,2.3), head/neck 1.1 (95% CI 0.7,1.9), anal 1.1 (95% CI 0.4,2.9), lung 1.0 (95% CI 0.5,1.9), and colorectal 0.9 (95% CI 0.4,1.9) incident diagnoses/cases per 1000 person-years. Among ADCs, the incidence rates were as follows: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) 0.9 (95% CI 0.3,2.5), cervical cancer 0.7 (95% CI 0.1,4.4), and Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) 0.5 (95% CI 0,7.1) diagnoses/cases per 1000 person-years.

TABLE 3:

INCIDENT CANCERS AMONG COHORT PARTICIPANTS JANUARY 2011 TO DECEMBER 2017

| Incident Rate, per 1,000 (95% CI) |

Median Age (IQR) | Median CD4+ T Lymphocyte count cells/μL(IQR) |

HIV RNA ≥200 copies/mL n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-AIDS Defining Cancers (n=278) | 12.1 (10.7, 13.8) | 58 (51-64) | 436.5 (270.5-689) | 38 (13.7) |

| Breast (n=17) | 2.6 (0.5, 12.1) | 52 (44-57) | 450 (362-879) | 2 (11.8) |

| Prostate (n=44) | 2.3 (1.2, 4.3) | 61 (55.5-64.5) | 397 (305.5-576) | 7 (16.3) |

| Skin (n=37) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.6) | 56.5 (50-65) | 439 (278-686) | 1 (2.9) |

| Non-Melanoma (n=6) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.3) | 57 (50-65) | 414 (277-686) | 1 (3.2) |

| Melanoma (n=31) | 0.2 (0, 2.8) | 55.5 (53-68) | 521.5 (480-576) | 0 (0) |

| Anal (n=29) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.9) | 53 (46-59) | 272.5 (168-420.5) | 4 (13.8) |

| Head/neck (n=29) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.9) | 64 (58-71) | 515.5 (360.5-707) | 1 (3.6) |

| Lung (n=26) | 1.0 (0.5, 1.9) | 61 (57-64) | 442.5 (231-879) | 4 (15.4) |

| Colorectal (n=24) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.9) | 54.5 (50.5-62.5) | 421 (180-619) | 5 (20.8) |

| Liver (n=14) | 0.5 (0, 73.2) | 62.5 (58-66) | 456 (284-720) | 1 (7.1) |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma (n=11) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.1) | 42 (34-51) | 604 (159-925) | 3 (27.3) |

| Renal (n=6) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) | 61 (55-65) | 614.5 (488-708) | 1 (16.7) |

| Other (n=75) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.4) | 56 (51-63) | 432 (242-689) | 13 (17.3) |

| AIDS Defining Cancers (n=41) | 1.6 (0.6, 4.6) | 49 (45-58) | 238 (138-632) | 13 (31.7) |

| Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (n=23) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.5) | 49 (46-58) | 311 (181-605) | 5 (21.7) |

| Cervical (n=5) | 0.7 (0.1, 4.4) | 50 (45-51) | 776 (349-1264) | 1 (20.0) |

| Kaposi's Sarcoma (n=13) | 0.5 (0, 7.1) | 49 (33-62) | 166 (83-238) | 7 (53.8) |

Predictors of Incident Cancers:

Factors associated with incident NADCs and ADCs are outlined in TABLE 4. In adjusted analyses, baseline HIV VL ≥200 copies/mL (aHR 2.19; 95% CI 1.06, 4.51; p=0.034) was a predictor of incident ADCs. Factors associated with incident NADCs in adjusted analyses were older age (aHR 1.33, per 5-year increase; 95% CI 1.33, 1.42; p <0.0001), lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count (aHR 0.96, per 50-cells/microliter increase; CI 0.93, 0.99; p=0.0064), and smoking history (aHR 1.34; CI 1.00, 1.78; p=0.049).

TABLE 4:

PREDICTORS OF INCIDENT AIDS-DEFINING AND NON-AIDS DEFINING CANCER DIAGNOSES

| AIDS-Defining Cancer (n=7,751) |

Non-AIDS Defining Cancer (n=7,595) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted * | Unadjusted | Adjusted * | |

| Hazard Ratio | Hazard Ratio | Hazard Ratio | Hazard Ratio | |

| Age (per 5-year increase) | 1.08 (0.95, 1.23) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.44) | 1.33 (1.24, 1.42) |

| Male sex at birth | 1.54 (0.71, 3.33) | 1.17 (0.43, 3.17) | 1.17 (0.86, 1.60) | 0.87 (0.60, 1.27) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.14 (0.47, 2.73) | 1.03 (0.39, 2.75) | 1.42 (1.02, 1.99) | 1.35 (0.92, 1.98) |

| Hispanic | 0.99 (0.24, 4.13) | 1.07 (0.24, 4.78) | 0.36 (0.13, 0.96) | 0.53 (0.19, 1.42) |

| Mode of HIV Transmission | ||||

| Men who have sex with men | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Heterosexual | 0.52 (0.25, 1.10) | 0.66 (0.25, 1.74) | 1.00 (0.73, 1.39) | 0.84 (0.56, 1.26) |

| Injection Drug Use | 0.46 (0.11, 1.97) | 0.48 (0.10, 2.38) | 2.03 (1.36, 3.05) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.58) |

| Private (vs. public) insurance | 0.95 (0.46, 1.97) | 1.12 (0.44, 2.85) | 0.84 (0.62, 1.15) | 1.02 (0.69, 1.52) |

| Unemployed (vs. employed) | 0.69 (0.28, 1.69) | 0.99 (0.41,2.42) | 1.03 (0.73, 1.46) | 0.95 (0.62, 1.46) |

| History of substance abuse | 1.66 (0.59, 4.67) | 1.80 (0.59, 5.48) | 1.49 (0.93, 2.38) | 1.44 (0.87, 2.39) |

| History of smoking | 1.19 (0.64, 2.21) | 1.17 (0.61, 2.26) | 1.58 (1.20, 2.07) | 1.34 (1.00, 1.78) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (per 5-year increase) | 1.10 (0.91, 1.34) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24) | 1.23 (1.13, 1.33) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.15) |

| Nadir CD4+ T lymphocyte count (cells/ μL) | ||||

| >500 | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 200-500 | 1.66 (0.47, 5.86) | 1.59 (0.42, 5.97) | 1.35 (0.86, 2.11) | 1.17 (0.72, 1.90) |

| <200 | 4.28 (1.30, 14.14) | 3.86 (0.97, 15.27) | 2.19 (1.42, 3.37) | 1.42 (0.83, 2.40) |

| Baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count (per 50-cells/μL increase) | 0.93 (0.88, 0.99) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) |

| Baseline HIV viral load ≥200 copies/mL | 2.04 (1.06, 3.94) | 2.19 (1.06, 4.51) | 0.95 (0.67, 1.33) | 1.07 (0.75, 1.54) |

| Chronic Hepatitis B infection | 1.06 (0.15, 7.71) | --- | 1.24 (0.55, 2.79) | --- |

| Chronic Hepatitis C infection | 0.60 (0.18, 1.93) | --- | 1.38 (0.96, 1.97) | --- |

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, CD4+ T lymphocyte nadir, baseline CD4+ T, and viral load were included in multivariable models for the adjusted analyses for AIDS-Defining Cancers. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, CD4+ T lymphocyte nadir, baseline CD4+ T, and smoking were included in multivariable models for the adjusted analyses for non-AIDS-Defining Cancers For AIDS-defining cancers. We explored removing HIV viral load from the model for AIDS defining cancers due to potential collinearity with baseline

p<0.05.

Age at Cancer Diagnosis:

The median age at the time of incident cancer diagnosis was 58 years for NADCs versus 49 for ADCs. The median age at the time of diagnosis of CRC was 55 years, and 16.7% (n=4) of the incident CRCs were diagnosed prior to the age of recommended screening. The median age at breast cancer diagnosis was 52 years, and 41.2% (n=7) were diagnosed prior to the age of recommended screening. The median age at the time of lung cancer diagnosis was 61 years, and 7.7% (n=2) were diagnosed prior to the age of recommended screening.

Cancer Screening:

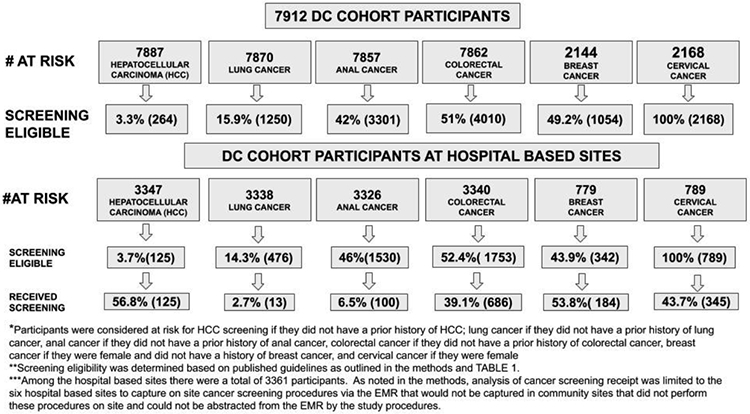

FIGURE 2 highlights the DC cohort participants at risk for cancers and the receipt of screening among those at risk and eligible. Among those at risk, 49.2% of women were eligible for breast cancer screening; all women without a prior history of cervical cancer were eligible for cervical cancer screening; 15.9% of participants for lung cancer screening; 51% of participants for CRC screening; 42% of participants eligible for anal HPV screening; and 3.3% of participants were eligible for HCC screening.

FIGURE 2:

CANCER SCREENING ELIGIBILITY AND PERFORMANCE IN THE DC COHORT

The receipt of cancer screening among participants receiving HIV care at the six hospital-based sites in the cohort is outlined in FIGURE 2. Among 342 eligible women, 53.8% (n=184) had at least one mammogram completed during the follow-up period. Among those eligible for cervical cancer screening 43.7% (n=345/789) completed screening. Of those eligible for lung cancer screening 2.7% (n=13/476) underwent a computerized tomography (CT) of the chest. Among those eligible for CRC screening 39.1% (n= 686/1753) had evidence of at least one screening procedure performed. Finally, among those eligible for HCC screening 56.8% (n=71/125) had evidence of abdominal ultrasound.

In addition to ascertainment of cancer screening at the six hospital-based sites, we determined the receipt of cancer screening among those eligible who received primary care services at a DC Cohort site. Among those eligible, 57% (n=83) received breast, 43% (n=117) cervical, 65% (n=49) HCC, 49% (n=463) colorectal, 13% (n=81) anal HPV testing, and 2% (n=5) lung cancer screening.

Discussion

In this cohort of PLWH, we found a higher incidence of NADCs with the highest incident cancers being breast and prostate. Higher baseline VL was associated with ADCs, and factors associated with NADCs included baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count, older age, and smoking history. The majority of cancer diagnoses ascertained in this analysis would have been captured by current screening practices; however, a clinically significant number of breast cancer diagnoses occurred prior to age 50. Performance of cancer screening was poor as less than 60% of eligible persons had any ascertained cancer screenings. This analysis adds to the growing body of literature describing shifting cancer incidence among PLWH, and also describes real-world performance of cancer screening in a clinical cohort of in-care PLWH.

While direct comparisons to our clinical cohort cannot be made to other observational cohort studies due to differences in study methodology and participant population, these older studies including the NA-ACCORD (1996-2009), the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (1984-2007), the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (1994-2001), and the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (1999-2008) showed higher incident rates of ADCs in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and early HAART eras as compared to NADCs.(Hessol et al., 2004; Park et al., 2014; Seaberg et al., 2010; Silverberg et al., 2015) Our observation of higher incidence of NADCs in this current era of effective cART is expected given the high uptake of HIV treatment and associated immune recovery. Thus we are beginning to observe the emergence of NADCs as the predominant malignancies in the setting of HIV as projected by other studies where by 2030 the most common sites of cancers among PLWH are anticipated to be NADCs (prostate, lung, and liver).(Shiels et al., 2018)

From our analysis, we cannot compare individual cancer incidence rates to that of other cohorts or population studies, but we did note the numerical ordering of incident cancer sites in this analysis more closely approximated that of the US general population than earlier studies with some important differences. In 2015, there were more than 15 million persons in the US living with cancer with the most common sites being female breast, lung and bronchus, prostate, and colorectal cancers respectively.(SEER Research Data 1973-2015, n.d.) Notable differences in our analysis of were higher relative rates of anal, head/neck, and skin cancers when compared to other incident cancer diagnoses in our cohort.

In this cohort we found that skin cancer had the 3rd highest incidence rate. Prior studies note increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancers in PLWH, specifically increased rates of basal cell carcinoma in men and/or MSM. The exact mechanisms of increased risk are unknown but may be related to the degree of immunosuppression or behavioral factors, such as increased sun exposure among certain subpopulations. (Omland et al., 2018; Silverberg et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2016) While there are no consensus guidelines for skin cancer screening among PLWH our data suggests that routine screening for skin cancers among PLWH may need to be considered The risks, benefits, and implementation of this more aggressive recommendation require further study.

Similar to skin cancer, the incident rates of anal and head/neck cancer were higher in order of incidence among PLWH as compared rankings in the general population. In a previous analysis of persons living with AIDS in DC, the rates of oral and anal cancers doubled between the early and late post-HAART eras. Presumably these head and neck malignancies are related to co-infection with HPV, but there are no current recommendations for cancer screening for head and neck cancers.(Beachler & D’Souza, 2013) There are guidelines from the IDSA as relates to HPV-associated genital disease.(Aberg et al., 2014) These include recommendations for screening MSM, women with a history of receptive anal intercourse or abnormal cervical PAPs, and all PLWH with a history of genital warts.(Aberg et al., 2014) Recommendations for anal HPV screening have not yet reached a consensus as in the 2015 CDC Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment guidelines authors note that data was insufficient to recommended routine anal HPV screening.(Workowski, Kimberly A., and Gail A. Bolan, 2015)

Forty-two percent of our cohort were eligible for anal HPV screening based on IDSA recommendations, but only 6.5% of the persons eligible at the six hospital-based sites had documented screening. We postulate that the lower documented performance is related to lack of consensus guidelines. Ongoing studies including the Anal Cancer HSIL Outcomes Research (ANCHOR) Study will provide evidence to guide appropriate management.(The Anchor Study, n.d.)

Cervical cancer was the second most common incident ADC and 9th most common incident cancer in this cohort. All of the women in the cohort were eligible for screening based on current IDSA recommendations.(Aberg et al., 2014) However, only 44% of women at the six hospital based sites had documented screening. In the general US population, cervical cancer screening rates were 79%.(Cervical Cancer Screening, n.d.) Among women living with HIV, the screening rates have been reported between 58% to 78% in various populations.(Leece et al., 2010; Rahangdale et al., 2010; Simonsen et al., 2014)

In our analysis, breast cancer had the highest incidence. Previous studies suggested that breast cancer occurs less frequently in women living with HIV/AIDS as compared to the general population However, newer data show increased breast cancer risk over time for women living with HIV/AIDS.(Goedert et al., 2006) In our cohort, a large population of women (49%) were eligible for screening. However, only 54% of those eligible at hospital-based clinic sites underwent any documented screening during follow-up. Other analyses of breast cancer screening among women living with HIV in various settings also reported lower screening rates between 65% and 67%.(Preston-Martin et al., 2002; Simonsen et al., 2014) In the US general population breast screening rates were reported at 72% in 2015.(Breast Cancer Screening, n.d.)

Forty-one percent of the breast cancers in this cohort were diagnosed prior to age 50, the age of definite recommended screening by the IDSA and USPSTF.(Aberg et al., 2014; Siu & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2016) However, the American College of Gynecology (ACOG) and American Cancer Society (ACS) recommend that mammography be offered at starting at age 40 and recommended no later than age 50 or age 45 respectively if not already initiated for women at average risk.(Oeffinger et al., 2015; Practice Bulletin, Number 179, July 2017, Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women, n.d.) The American College of Radiology (ACR), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend screening initiation at age 40 for women at average risk.(Monticciolo et al., 2017; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2018) Given the findings in this analysis, initiation of breast cancer screening at age 40 as suggested by these guidelines may be appropriate. In addition to better implementation of current recommended screening guidelines, further study is needed for the appropriate time of initiation and frequency of breast cancer screening in this population, as well as why newer data appears to indicate an increased early risk of breast cancer compared with the general population.(McCormack et al., 2018)

Recommendations from the UPSTF were approximated for lung and CRC screening, and similar to breast and cervical cancers screening performance was low.(Moyer & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2014; US Preventive Services Task Force et al., 2016) Thirty-nine percent of the cohort had ascertained CRC screening and 2.7% lung cancer. The USPSTF recommendations which were published in 2014 were applied to the entire follow-up period and thus may have underestimated the performance of lung cancer screening. However, our findings are consistent with that of the general US population with low performance of this screening. In the general US population, lung cancer screening was performed in 1.9% to 5.5% of those eligible for screening.(Danh Pham, Shruti Bhandari, Malgorzata Oechsli, Christina M Pinkston, Goetz H. Kloecker et al., 2018)(Lung Cancer Screening, n.d.) Screening performance for CRCs was 67.3% in the general population and among PLWH has been reported as around 36% for those receiving Medicaid.(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Quick Facts: Colorectal Cancer Screening in U.S, n.d.; Keller et al., 2014) The majority of these CRC diagnoses in this cohort would have been captured by current screening recommendations with only 17% of CRCs being diagnosed prior to the age of recommended screening, and with lung cancers 8% being diagnosed prior to the age of recommended screening.

This analysis was conducted among in-care PLWH and thus may provide a real-world description of cancer screening performance and cancer incidence. However, our results may not be reflective of the entire population of PLWH including those not in-care, and other clinical sites in DC. Analysis of cancer screening was performed for hospital-based sites as well as for participants who received primary care services at their DC cohort study site. As noted in the methodology, we used hospital-based sites for analysis and ascertainment of screening practices as this would allow for greater capture of CPT coding at certain sites. If participants did not receive primary care services from their HIV care provider or within the same health system receipt of these services may have not been captured in the hospital-based analysis and therefore could have been underreported. However, in our analysis of those who received primary care at their DC Cohort site cancer screening rates were similar suggesting that we may have captured a representative trend in cancer screening practices. Provider intent in ordering imaging (.i.e. CT or ultrasound) or other procedures was unknown and may also skew assessment of cancer screening. We also were unable to assess screening completed prior to the observation period for each participant. These factors likely contribute to our lower ascertained completion of cancer screening among PLWH for cervical, breast, or colorectal cancer than has been reported. Previously reported screening rates among PLWH for these conditions as noted above were still lower than that of the general US population which demonstrate significant disparities in age/diagnosis related cancer screenings.

Our analysis of cancer incidence was performed using ICD-9/10 coding and is dependent on accurate and complete entry into the EMR. There was no linkage to a cancer registry or adjudication process performed (other than manual entry of cancer diagnoses at DC Cohort enrollment). Thus, our results are subject to the completeness of ICD-9/10 coding data from the individual DC cohort study sites. These codes are used for diagnoses and reasons for visits in health care settings, and if the cancer diagnosis is not related to a reason for a visit to a particular healthcare organization or otherwise noted via ICD-9/10 coding during a visit to a DC then the diagnosis may have not been ascertained. Previous studies have noted that secondary diagnoses are frequently omitted.(Horsky et al., 2017) Based on these factors incident cancer diagnoses may be underreported..

Despite these limitations, our study provides an assessment of cancer incidence and screening in a population of PLWH in a variety of real world-care settings including academic centers, community-based clinics, community-based hospital sites, and government facilities which is informative for improving cancer screening practices.

Conclusions

We demonstrate a shift in incident cancer diagnoses among PLWH to that of predominantly NADCs as projected in prior studies. Performance of cancer screening in this cohort was poor compared to reported screening rates in the US and in select populations of PLWH. Lower rates of cancer screening among PLWH may be related to differences in access to care, socioeconomic, healthcare providers, or other structural barriers. These low rates of screening represent missed opportunities for early diagnosis and treatment. Further study is needed to assess barriers to screening and to develop targeted implementation strategies of current recommendations. In addition, PLWH may have unique preventative health care needs related to cancer screening including more aggressive skin cancer screening and/or earlier initiation of breast cancer screening. Applicability of current guidelines for cancer screening should be assessed for PLWH.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health under Grant UM1 AI69503. Data was collected by the DC Cohort investigators and research staff at: Cerner Corporation (Jeffrey Binkley, Cheryl Akridge, Thilia Subramanian, Qingjiang Hou, Stacey Purinton, Nabil Rayeed, Rob Taylor); Children’s National Medical Center Adolescent (Lawrence D’Angelo) and Pediatric (Natella Rakhmanina) clinics; The Senior Deputy Director of the DC Department of Health HAHSTA (Michael Kharfen); Family and Medical Counseling Service (Michael Serlin); Georgetown University (Princy Kumar); George Washington Medical Faculty Associates(David Parenti); George Washington University Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics (Anne Monroe, James Peterson, Lindsey Powers Happ, Maria Jaurretche, Brittany Wilbourn, and Kevin Trac); Howard University (Ronald Wilcox); La Clínica Del Pueblo (Ricardo Fernandez); MetroHealth (Annick Hebou); National Institutes of Health (Carl Dieffenbach);Unity Health Care (Gebeyehu Teferi); Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Debra Benator); Washington Hospital Center (Maria Elena Ruiz); Whitman-Walker Health (David Hardy, Deborah Goldstein); Kaiser Permanente (Michael Horberg). We would also like to acknowledge the Research Assistants at all of the participating sites, the DC Cohort Community Advisory Board and the DC Cohort participants.

This research has been facilitated by the services and resources provided by the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (AI117970), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIDDK, NIMHD, NIDCR, NINR, FIC and OAR. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no relevant disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA, & Infectious Diseases Society of America. (2014). Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 58(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. (2017). Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet. HIV, 4(8), e349–e356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beachler DC, & D’Souza G (2013). Oral human papillomavirus infection and head and neck cancers in HIV-infected individuals. Current Opinion in Oncology, 25(5), 503–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breast Cancer Screening. (n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2018, from https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/breast_cancer

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). HIV Surveillance Report, 2016; 28 . http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Quick Facts: Colorectal Cancer Screening in U.S. (n.d.)· https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/pdf/QuickFacts-BRFSS-2016-CRC-Screening-508.pdf

- 7.Cervical Cancer Screening. (n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2018, from https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/cervical_cancer

- 8.Pham Danh, Bhandari Shruti, Oechsli Malgorzata, Pinkston Christina M, Kloecker Goetz H., James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, James Graham Brown Cancer Center, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, US, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, University of Louisville School of Public Health, Information Sciences, Louisville, KY, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Hematology, & Medical Oncology, James Brown Graham Cancer Center, Louisville, KY. (2018). Lung cancer screening rates: Data from the lung cancer screening registry. https://meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/158432/abstract [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goedert JJ, Schairer C, McNeel TS, Hessol NA, Rabkin CS, Engels EA, & HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study. (2006). Risk of breast, ovary, and uterine corpus cancers among 85,268 women with AIDS. British Journal of Cancer, 95(5), 642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg AE, Hays H, Castel AD, Subramanian T, Happ LP, Jaurretche M, Binkley J, Kalmin MM, Wood K, Hart R, & DC Cohort Executive Committee. (2016). Development of a large urban longitudinal HIV clinical cohort using a web-based platform to merge electronically and manually abstracted data from disparate medical record systems: technical challenges and innovative solutions. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA, 23(3), 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Zhu AX, Murad MH, & Marrero JA (2018). AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology , 67(1), 358–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernández-Ramírez RU, Shiels MS, Dubrow R, & Engels EA (2017). Cancer risk in HIV-infected people in the USA from 1996 to 2012: a population-based, registry-linkage study. The Lancet. HIV. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30125-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hessol NA, Seaberg EC, Preston-Martin S, Massad LS, Sacks HS, Silver S, Melnick S, Abulafia O, Levine AM, & WIHS Collaborative Study Group. (2004). Cancer risk among participants in the women’s interagency HIV study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 36(4), 978–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horsky J, Drucker EA, & Ramelson HZ (2017). Accuracy and Completeness of Clinical Coding Using ICD-10 for Ambulatory Visits. AMIA … Annual Symposium Proceedings / AMIA Symposium. AMIA Symposium, 2017, 912–920. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller SC, Momplaisir F, Lo Re V, Newcomb C, Liu Q, Ratcliffe SJ, & Long JA (2014). Colorectal cancer incidence and screening in US Medicaid patients with and without HIV infection. AIDS Care, 26(6), 716–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. (2017, December20). Mortality in the United States, 2016. NCHS Data Brief, no 293. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db293.htm [PubMed]

- 17.Leece P, Kendall C, Touchie C, Pottie K, Angel JB, & Jaffey J (2010). Cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women. Retrospective cohort study from a tertiary care HIV clinic. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien, 56(12), e425–e431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lung Cancer Screening. (n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2018, from https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/lung_cancer

- 19.Marcus JL, Chao CR, Leyden WA, Xu L, Quesenberry CP Jr, Klein DB, Towner WJ, Horberg MA, & Silverberg MJ (2016). Narrowing the Gap in Life Expectancy Between HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Individuals With Access to Care. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 73(1), 39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormack VA, Febvey-Combes O, Ginsburg O, & Dos-Santos-Silva I (2018). Breast cancer in women living with HIV: A first global estimate. International Journal of Cancer. Journal International Du Cancer, 143(11), 2732–2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monticciolo DL, Newell MS, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Moy L, Monsees B, Kopans DB, Eby PR, & Sickles EA (2017). Breast Cancer Screening for Average-Risk Women: Recommendations From the ACR Commission on Breast Imaging. Journal of the American College of Radiology: JACR, 14(9), 1137–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moyer VA, & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2014). Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(5), 330–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2018). Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf

- 24.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih Y-CT, Walter FC, Church TR, Flowers CR, FaMonte SJ, Wolf AMD, DeSantis C, Fortet-Tieulent J, Andrews K, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Saslow D, Smith RA, Brawley OW, Wender R, & American Cancer Society. (2015). Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 314(15), 1599–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omland SH, Ahlstrom MG, Gerstoft J, Pedersen G, Mohey R, Pedersen C, Kronborg G, Farsen CS, Kvinesdal B, Gniadecki R, Obel N, & Omland LH (2018). Risk of skin cancer in patients with HIV: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 79(4), 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park FS, Tate JP, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Rimland D, Goetz MB, Gibert C, Brown ST, Kelley MJ, Justice AC, & Dubrow R (2014). Cancer Incidence in HIV-Infected Versus Uninfected Veterans: Comparison of Cancer Registry and ICD-9 Code Diagnoses. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 5(7), 1000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter K, Babiker A, Bhaskaran K, Darbyshire J, Pezzotti P, Porter K, Walker AS, & CASCADE Collaboration. (2003). Determinants of survival following HIV-1 seroconversion after the introduction of HAART. The Lancet, 362(9392), 1267–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Practice Bulletin, Number 179, July 2017, Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women. (n.d.). https://www.acog.org/-/media/Practice-Bulletins/Committee-on-Practice-Bulletins---Gynecology/Public/pb179.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20190108T2141432032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Preston-Martin S, Kirstein LM, Pogoda JM, Rimer B, Melnick S, Masri-Lavine L, Silver S, Hessol N, French AL, Feldman J, Sacks HS, Deely M, & Levine AM (2002). Use of mammographic screening by HIV-infected women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). Preventive Medicine, 34(3), 386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rahangdale L, Samquist C, Yavari A, Blumenthal P, & Israelski D (2010). Frequency of cervical cancer and breast cancer screening in HIV-infected women in a county-based HIV clinic in the Western United States. Journal of Women’s Health , 79(4), 709–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riedel DJ, Tang LS, & Rositch AF (2015). The role of viral co-infection in HIV-associated non-AIDS-related cancers. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 12(3), 362–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seaberg EC, Wiley D, Martinez-Maza O, Chmiel JS, Kingsley U, Tang Y, Margolick JB, Jacobson LP, & Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). (2010). Cancer incidence in the multicenter AIDS Cohort Study before and during the HAART era: 1984 to 2007. Cancer, 116(23), 5507–5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SEER Research Data 1973-2015. (n.d.). Retrieved September 6, 2018, from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html

- 34.Shiels MS, Islam JY, Rosenberg PS, Hall HI, Jacobson E, & Engels EA (2018). Projected Cancer Incidence Rates and Burden of Incident Cancer Cases in HIV-Infected Adults in the United States Through 2030. Annals of Internal Medicine, 168(12), 866–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverberg MJ, Lau B, Achenbach CJ, Jing Y, Althoff KN, D’Souza G, Engels EA, Hessol NA, Brooks JT, Burchell AN, Gill MJ, Goedert JJ, Hogg R, Horberg MA, Kirk GD, Kitahata MM, Korthuis PT, Mathews WC, Mayor A, … North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS. (2015). Cumulative Incidence of Cancer Among Persons With HIV in North America: A Cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(7), 507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM, Quesenberry CP Jr, Engels EA, & Asgari MM (2013). HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 105(5), 350–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simonsen SE, Kepka D, Thompson J, Warner EL, Snyder M, & Ries KM (2014). Preventive health care among HIV positive women in a Utah HIV/AIDS clinic: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Women’s Health, 14(1), 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siu AL, & U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 164(4), 279–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, Morlat P, Pradier C, Reiss P, Kowalska JD, de Wit S, Law M, el Sadr W, Kirk O, Friis-Moller N, Monforte AD, Phillips AN, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD, & D:A:D Study Group. (2014). Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. The Lancet, 384(9939), 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang K-M, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Brown RS Jr., Bzowej NH, & Wong JB (2018). Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology , 67(4), 1560–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Anchor Study. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2019, from https://anchorstudy.org/

- 42.US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, García FAR, Gillman MW, Harper DM, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Owens DK, Phillips WR, Phipps MG, Pignone MP, & Siu AL (2016). Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 315(23), 2564–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Workowski Kimberly A., and Bolan Gail A.. (2015). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports, 64, RR – 03. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yarchoan R, & Uldrick TS (2018). HIV-Associated Cancers and Related Diseases. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(11), 1029–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan Y (2011). Multiple Imputation Using SAS Software. Journal of Statistical Software, Articles, 45(6), 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao H, Shu G, & Wang S (2016). The risk of non-melanoma skin cancer in HIV-infected patients: new data and meta-analysis. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 27(7), 568–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]