ABSTRACT

Dengue fever, caused by dengue virus (DENV), is the most prevalent arthropod-borne viral disease and is endemic in many tropical and subtropical parts of the world, with an increasing incidence in temperate regions. The closely related flavivirus Zika virus (ZIKV) can be transmitted vertically in utero and causes congenital Zika syndrome and other birth defects. In adults, ZIKV is associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome. There are no approved antiviral therapies against either virus. Effective antiviral compounds are urgently needed. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (AAs) are a specific class of nitrogen-containing compounds produced by plants of the Amaryllidaceae family with numerous biological activities. Recently, the AA lycorine was shown to present strong antiflaviviral properties. Previously, we demonstrated that Crinum jagus contained lycorine and several alkaloids of the cherylline, crinine, and galanthamine types with unknown antiviral potential. In this study, we explored their biological activities. We show that C. jagus crude alkaloid extract inhibited DENV infection. Among the purified AAs, cherylline efficiently inhibited both DENV (50% effective concentration [EC50], 8.8 μM) and ZIKV replication (EC50, 20.3 μM) but had no effect on HIV-1 infection. Time-of-drug-addition and -removal experiments identified a postentry step as the one targeted by cherylline. Consistently, using subgenomic replicons and replication-defective genomes, we demonstrate that cherylline specifically hinders the viral RNA synthesis step but not viral translation. In conclusion, AAs are an underestimated source of antiflavivirus compounds, including the effective inhibitor cherylline, which could be optimized for new therapeutic approaches.

KEYWORDS: Amaryllidaceae, alkaloids, flavivirus, cherylline, antivirals, dengue virus, Zika virus, lycorine

INTRODUCTION

Dengue fever is a viral disease caused by dengue virus (DENV), a flavivirus related to Zika virus (ZIKV) and belonging to the family Flaviviridae. Both viruses are transmitted to humans through biting of female mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti or Aedes albopictus (1). DENV and ZIKV possess an ∼11-kb-long positive-sense stranded RNA genome encoding capsid (C), membrane precursor (prM), and envelope (E) structural proteins and NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 nonstructural proteins (2–4). To date, four serotypes of DENV (DENV1 to -4) are described as the cause of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome, both being potentially fatal (5, 6). Nearly four billion individuals are at risk of contracting dengue fever. An estimated 400 million people catch it every year. Between 50 and 100 million human symptomatic cases are reported annually in tropical and subtropical regions, with a yearly death toll of 20,000 individuals, most of them being children (7), posing a considerable threat for public health in over 100 countries (8). The number of cases is constantly increasing. From 2017 to 2018, two outbreaks associated with DENV-1 occurred in Senegal (9), and DENV is now present in more temperate regions such as southern Europe.

ZIKV infection is mostly asymptomatic or associated with mild symptoms in adults, but it can cause Guillain-Barré syndrome (10, 11). Fetal ZIKV infection causes more serious conditions, such as the congenital Zika syndrome and other severe birth defects. During the 2015 ZIKV outbreak in Brazil, 4,300 children were born with microcephaly (10).

To date, there are no approved antiviral therapies against DENV or ZIKV and no vaccine for ZIKV (12). In the case of DENV, the efficacy of the approved tetravalent vaccine Dengvaxia is not optimal for all serotypes, and its use is not recommended for DENV-seronegative individuals (13, 14). Therefore, effective compounds inhibiting ZIKV and DENV replication are urgently required, and drugs with broad-spectrum activity against several pathogenic flaviviruses would definitely constitute an asset in the therapeutic arsenal.

Medicinal plants such as Amaryllidaceae contain alkaloids with various biological activities, including antimosquito activity against Aedes aegypti and antiviral properties (15–19). The Amaryllidaceae Crinum macawonii methanolic extract inhibits in vitro infection of yellow fever virus (YFV) and Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), two flaviviruses (20). Aqueous and organic extracts from Crinum jagus contain molecules exhibiting anti-inflammatory (21), antibacterial (22), and antienteroviral activities (23), while their effect on flavivirus replication remains unknown. We isolated the Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (AAs) lycorine, sanguinine, crinine, gigancrinine, flexinine, cherylline, gigantelline, and gigantellinine and hippadine (an amide close to lycorine) from C. jagus (giganteum) and showed that some display cytotoxic activity and antiacetylcholinesterase potential (24). In preceding studies, lycorine was shown to inhibit Flaviviridae such as the flaviviruses DENV, ZIKV, YFV, and JEV and several viruses from other families, including Retroviridae (HIV-1) and Coronaviridae, as well as DNA viruses (25–32). Except for lycorine, the antiviral potential of AAs has been poorly studied. Continuing our screening of biological activities of native and understudied Amaryllidaceae from Senegal, we investigated C. jagus’s alkaloid potential. We hypothesized that C. jagus extract displays antiflaviviral properties and that it contains alkaloids with antiflaviviral potential in addition to lycorine.

In this study, we assessed the in cellulo antiviral activity of AAs isolated from C. jagus and identified cherylline as a novel inhibitor of the DENV and ZIKV life cycles. Using time-of-drug-addition and -removal assays, as well as modified DENV genomes, we further showed that the viral RNA replication step of the DENV life cycle is the main target of cherylline. This comprehensive assessment uncovers cherylline as a new natural product candidate to be optimized for the development of therapeutics to fight flavivirus infections.

RESULTS

Crinum jagus alkaloid extract displays anti-DENV activity.

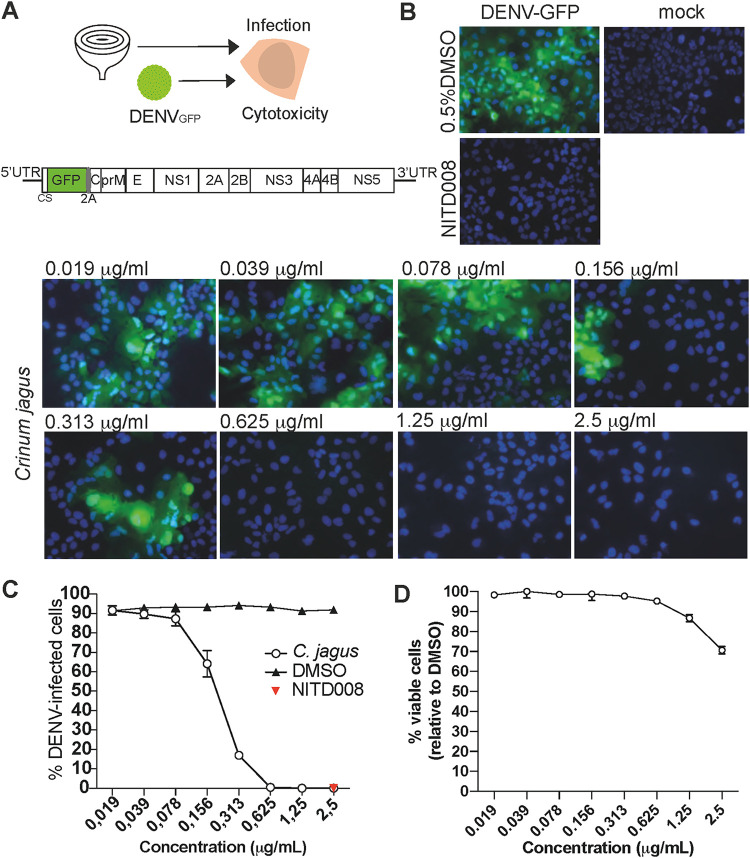

First, we evaluated the effect of C. jagus extract on the replication of DENV. We used green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing reporter DENV particles for infection (Fig. 1A to C). In this system, the GFP coding sequence is included in the unique open reading frame of the viral RNA genome; 103 nucleotides of DENV capsid gene are duplicated and cloned upstream of gfp, fused to the capsid gene with a 2A peptide. Gfp is translated in-frame with the polyprotein. The 2A peptide allows GFP to be proteolytically released from DENV polyprotein during or shortly after translation (33). Hence, GFP fluorescence is directly proportional to the extent of polyprotein production. This allows the detection of viral replication in infected cells using microscopy or flow cytometry. The inhibitory properties of C. jagus crude extract were evaluated in Huh7 hepatocarcinoma cells, a classical model for flavivirus study. NS5 RNA polymerase inhibitor NITD008 was used as a positive control (34, 35). At concentrations ranging from 0.078 to 2.5 μg/ml, DENVGFP replication was significantly inhibited by the extract (Fig. 1B and C). Viral inhibition followed a dose-dependent response with an 50% effective concentration [EC50] of 0.25 μg/ml (Fig. 1C). At 0.625 μg/ml, no infection could be detected by either flow cytometry or microscopy. We also verified the cytotoxicity of C. jagus crude extract antiviral concentrations in Huh7 cells. Extracts were weakly cytotoxic at all concentrations, with a minimum of 71% of viable cells at the highest concentration of 2.5 μg/ml. At 0.625 μg/ml, 100% of the cells were viable, while 0% were infected (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Crinum jagus alkaloid extract’s anti-DENV activity. (A) Schematic experimental design of the antiviral assay using Crinum jagus bulbs and DENV, with DENVGFP construct genome representation. In this system produced by Fischl and Bartenschlager (33), 103 nucleotides of DENV capsid gene were duplicated and cloned upstream of gfp, which was then fused to the capsid gene with a 2A peptide (82). Gfp is replicated as part of the viral genome and translated as a component of the polyprotein. The 2A peptide allows GFP to be released from DENV polyprotein during or following the translation process. (B) Inhibition of DENVGFP infection with C. jagus alkaloid extract observed by inverted microscopy in Huh7 cells. Representative images are shown with cell nuclei stained with Hoechst33342 (blue) and DENV infection (green). (C) Anti-DENV activity of C. jagus crude extracts. The inhibition of DENVGFP infection in Huh7 cells by C. jagus alkaloid extract dilutions was measured by flow cytometry. (D) Cytotoxicity of C. jagus bulbs crude alkaloid extract in Huh7 cells as measured by the XTT [2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide salt] assay.

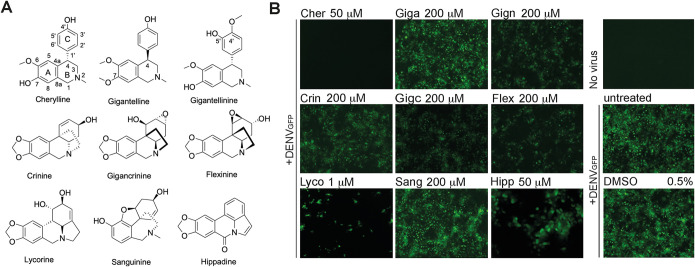

We next wanted to gain further knowledge into which AA present in C. jagus extract was responsible for the anti-DENV activity. Thus, we studied the nine alkaloids isolated from C. jagus, i.e., three cherylline-type (cherylline, gigantelline, and gigantellinine), three crinine-type (crinine, gigancrinine, and flexinine) one galanthamine-type (sanguinine), lycorine, as the sole representative of its own type, and hippadine (Fig. 2A). Excluding lycorine, the antiflaviviral abilities of these families of AAs are unknown. Huh7 cells were treated with AAs and infected with DENVGFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.15, 2 h later. Infection was visualized at 72 h postinfection (hpi) by detecting GFP using microscopy (Fig. 2B). Treatment with lycorine caused a sharp decrease in DENV-GFP-infected cells, confirming its strong anti-DENV activity. Interestingly, several other AAs inhibited DENVGFP infection. A notably strong antiviral effect was observed in wells in which cells were treated with 50 μM cherylline, with no detectable infection (Fig. 2B; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Other AAs displayed antiviral activity with an efficiency ranging from moderate (hippadine, flexinine, and gigantellinine) to weak (gigantelline) to very weak (sanguinine) at the chosen concentration. Interestingly, AAs of the same ring type with very similar structure, such as cherylline, gigantelline, and gigantellinine, presented very distinct strengths of inhibition on DENVGFP infectivity. Thus, differences in biological activity were not associated with a specific ring type.

FIG 2.

Screening of the anti-DENV activity of C. jagus isolated Amaryllidaceae alkaloids (AAs). (A) Structures of the nine AAs isolated from bulbs of C. jagus. Cherylline-type alkaloids comprised cherylline, gigantelline, and gigantellinine, while crinine types comprised crinine, gigancrinine, and flexinine. Lycorine, sanguinine, and hippadine were also isolated. (B) Anti-DENV activity of AAs. Huh7 cells were treated with compounds (AAs or DMSO vehicle) for 2 h and then infected with DENVGFP at an MOI of 0.15 for 72 h. Infectivity was visualized as GFP+ cells on an inverted microscope system with ×5 and ×20 (hippadine) objectives. The experiment was performed in triplicates at two dilutions. At least 3 pictures were taken from each well. One representative picture of the lowest dilution is displayed. Cher, cherylline; Giga, gigantelline; Gign, gigantellinine; Crin, crinine; Gigc, gigancrinine; Flex, flexinine; Lyco, lycorine; Sang, sanguinine; Hipp, hippadine.

Cherylline is a potent inhibitor of DENV.

Based on the antiviral activity screening from Fig. 2, we pursued the characterization of the four alkaloids with the highest anti-DENV activity.

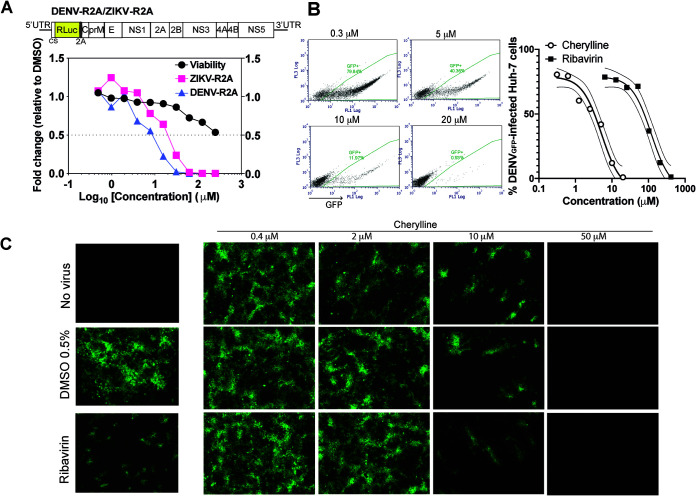

The antiviral activity of cherylline, hippadine, gigantellinine, and flexinine was studied using DENVR2A construct infection in Huh7.5 cells (Fig. 3A; Fig. S2A). DENVR2A is similar to DENVGFP, but Renilla luciferase replaces gfp as the reporter gene. Infection levels were measured at 48 hpi. Gigantellinine and flexinine anti-DENV activity required high concentrations (EC50, 104.6 and 63.4 μM, respectively; Fig. S2A). Hippadine antiviral activity on DENVR2A was difficult to distinguish from its cytopathic effect (EC50, 73.8; 50% cytotoxic concentration [CC50], 175.9 μM; stimulation index [SI], 2.38) (Fig. S3; Table 1). Cherylline inhibited DENVR2A replication at an EC50 of 8.8 μM (Fig. 3A). The cherylline CC50 was not reached at the highest tested concentration (250 μM). Its therapeutic selectivity index cannot be calculated but is predicted to be >28 (Table 1). Furthermore, the inhibitory activity of cherylline, our best candidate, was assessed by infecting Huh7 cells with DENVGFP in the presence of increasing concentrations (from 0.6 to 100 μM) of compound (Fig. 3B and C). Interestingly, cherylline was more potent than the guanosine analogue ribavirin at counteracting DENVGFP infection, with an EC50 of8 μM, similar to its effect on DENVR2A, compared to an EC50of 100 μM for ribavirin. By microscopy, no infected cells were observed at 50 μM, confirming our first experiment. Several foci of infected cells became visible at 10 μM, whereas most of the cells were infected at 2 μM, and there was no apparent difference with the control at 0.4 μM.

FIG 3.

Cherylline displays anti-DENV activity. (A) Impact of cherylline treatment on DENVR2A (purple) and ZIKVR2A (pink) replication was tested in Huh7.5 cells (MOI, 0.001), and viral-dependent luciferase luminescence was measured at 48 hpi. Cell viability (ATP) was assessed at 48 h. Results are displayed as fold changes in viability and replication, with 1 meaning no change compared to matched concentrations of DMSO-treated cells. (B) Treatment of Huh7 with cherylline dampened infectivity of DENVGFP replication (MOI, 0.15) in a dose-dependent manner, as measured by flow cytometry 72 hpi. (Left) representative dot plots; (right) percentage of infected Huh7 cells using 0.6 to 100 μM cherylline and 10 to 500 μM ribavirin as a positive control. The nonlinear regression curve fit is shown with the 95% of confidence interval in finer lines. (C) Representative pictures of Huh7 treated with different concentrations of cherylline and infected with DENVGFP at an MOI of 0.15. Ribavirin was used as a positive control, and DMSO as a negative control. Infected cells were visualized on an inverted microscope system at 72 hpi.

TABLE 1.

EC50, CC50, and selectivity index of AAs as calculated with GraphPad Prisma

| Alkaloids | CC50 (μM) | EC50 (μM) for |

SI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENVR2A | ZIKVR2A | DENVR2A | ZIKVR2A | ||

| Lycorine | 14.5 | 0.16 | 0.41 | 90.6 | 35.4 |

| Cherylline | >250 | 8.8 | 20.33 | >28 | >12.3 |

| Hippadine | 175.9 | 73.8 | 114 | 2.38 | 1.54 |

| Flexinine | >250 | 63.4 | 216.3 | >3.9 | >1.15 |

| Gigantellinine | >250 | 104.6 | >250 | >2.3 | ND |

EC50 was determined using DENV/ZIKVR2A infection from 0.05 to 25 μM for lycorine and NITD008 and from 0.5 to 250 μM for the others as in Fig. 2A. CC50 was calculated using the same concentrations in the same cell type, Huh7.5 at 48 h posttreatment. CC, cytotoxic concentration; EC, effective concentration; SI, therapeutic selectivity index; ND, not detected.

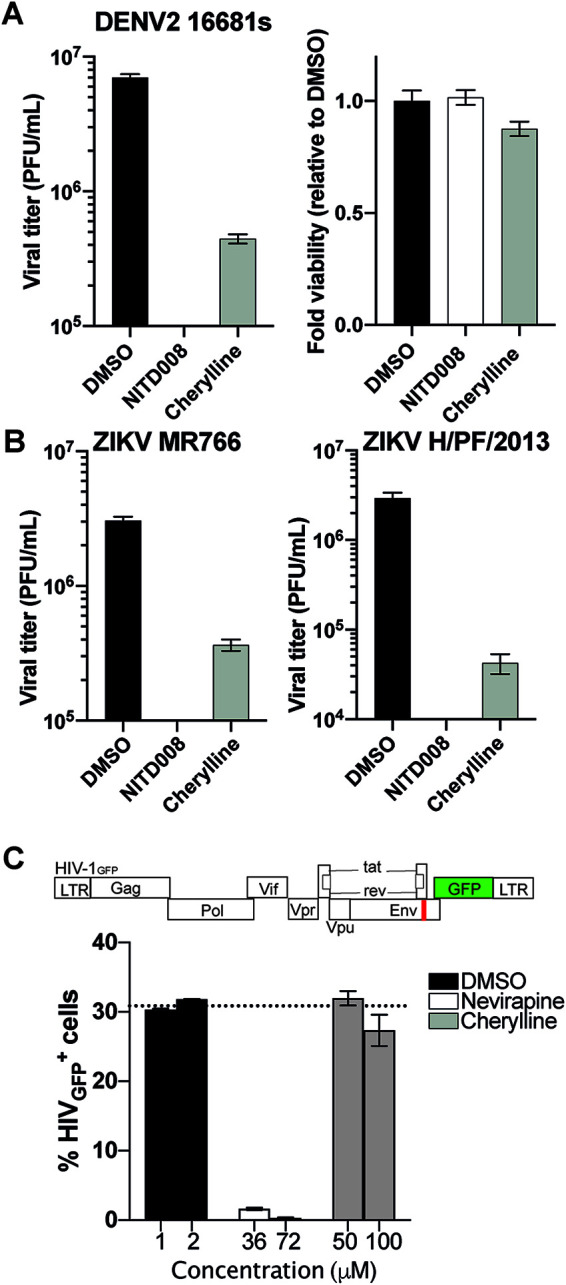

To validate the antiviral properties of cherylline, we tested its ability to prevent the production of infectious particles using wild-type viruses instead of reporter infectious systems. We infected Huh7.5 cells with viral strain DENV2 16881s, and then treated them with 50 μM of AAs 2 hpi (Fig. 4A). Then, 48 h later, cell supernatants were harvested, and extracellular infectious titers were determined using plaque assays. In parallel, viability was monitored. As expected, NITD008 completely hindered the production of infectious particles (Fig. 4A; Fig. S2B). Cherylline induced a 17-fold decrease in DENV 16881s viral titers (Fig. 4A; Fig. S2B). In contrast, hippadine, gigantellinine, and flexinine treatments exhibited no effects on DENV production (Fig. S2B). In conclusion, cherylline holds a notable anti-DENV potential.

FIG 4.

Cherylline displays antiviral activity against DENV and ZIKV. (A) Viral titers were measured by plaque assay on Vero E6 cells using the cytopathic WT DENV2 16881s strain. Huh7.5 cells were infected and treated 2 hpi with compounds. Then, 48 h later, supernatants were harvested and plated on Vero E6 cells (left). Fold changes in viability (ATP) were calculated at 48 hpi in Huh7.5 cells (right). (B) Viral titers were measured as in panel A on Vero E6 cells using cytopathic WT Uganda MR766 ZIKV strains (left) and French Polynesia H/PF/2013 (right). (C) THP-1 cells were treated with two concentrations of each compound in triplicates for 2 h and infected with VSV-G pseudotyped HIV-1GFP at an MOI of 1. The antiretroviral nevirapine was used as a positive control, and DMSO (vehicle), as negative a control. Results were analyzed by flow cytometry 72 hpi.

Cherylline efficiently inhibits ZIKV.

Next, we explored if the isolated AAs were also active on a closely related flavivirus. We examined the impact of cherylline, hippadine, gigantellinine, and flexinine treatment on ZIKVR2A replication in Huh7.5 cells (Fig. 3A; Fig. S2A). Cherylline interfered with the replication of ZIKV at noncytotoxic concentrations, with an EC50 of 20.3 μM and a selectivity index of >12.3 (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Hippadine, gigantellinine, and flexinine did not significantly impact ZIKVR2A replication (Fig. S2A).

To validate the anti-ZIKV properties of cherylline, we tested its ability to prevent the production of infectious particles using wild-type viral strains ZIKV H/PF/2013 and ZIKV MR766 instead of reporter infectious systems, as previously described. NITD008 completely hindered the production of infectious particles for both ZIKV strains (Fig. 4B; Fig. S2B). Cherylline diminished the pathogenic ZIKV H/PF/2013 strain viral titer by 100-fold and that of ZIKV MR766 by 88% (Fig. 4B; Fig. S2B).

In contrast, hippadine treatment resulted in a moderate 3-fold (70%) decrease in ZIKV H/PF/2013 viral titers, while gigantellinine and flexinine treatments exhibited marginal effects on ZIKV production (Fig. S2B). In conclusion, the plaque assay using wild-type (WT) viruses indicated that cherylline impedes the DENV2 and ZIKV life cycles.

Cherylline does not inhibit HIV-1 infection or the interferon response.

Lycorine has been described as a broad antiviral agent, inhibiting many viruses, including flaviviruses and retroviruses. To get insight into the specificity of cherylline antiviral spectrum, we examined its effect on VSV-G-pseudotyped-HIV-1GFP vector (Fig. 4C). This vector does not enter through fusion into cytoplasm, but rather, through endocytosis. It undergoes an incomplete single-cycle infection that includes uncoating, reverse transcriptase, nuclear transport, provirus integration, virus gene transcription, and mRNA translation. With the exception of Env and Nef, viral proteins are produced but do not assemble together to form new virions. Cherylline did not affect HIV-1 infection, nor did any of the AA tested (Fig. S2C). We also determined that cherylline did not trigger a significant amount of type I interferon (IFN) through monitoring of interferon-sensitive response element (ISRE) transcription compared to control treatments (Fig. S3A). These results demonstrate that cherylline specifically targets several flaviviruses with less cytotoxicity than lycorine (Table 1).

Cherylline targets DENV RNA replication.

We next investigated which step of the DENV life cycle was inhibited by cherylline. DENV viral replication kinetics have been widely studied (36). First, we performed a time course measurement of infection at 12, 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection with DENVGFP (MOI, 0.5) and DENVR2A (MOI, 0.005) (Fig. S4A and B). Cherylline inhibition of viral infection was measured through inhibition of GFP-infected cells (percentage), decrease of GFP and luciferase expression levels (mean fluorescence intensity and luminescence, respectively). A cherylline-induced decrease in viral RNA levels at 12 and 24 h during the first cycle of replication was confirmed using DENVGFP (MOI, 0.5) and WT viruses DENV2 16881s and ZIKV H/PF/2013 at an MOI of 2 (Fig. S4C), although the decrease in viral RNA (vRNA) was more pronounced in the case of DENVGFP and DENV2 16881s. As expected, vRNA levels decrease at later times, which is consistent with Renilla luciferase (Rluc) and GFP assays. The diminution of vRNA at 24 h (i.e., at early time points at which there is no contribution of viral spread in the assay) suggests an effect on the steps prior to the production of viral particles.

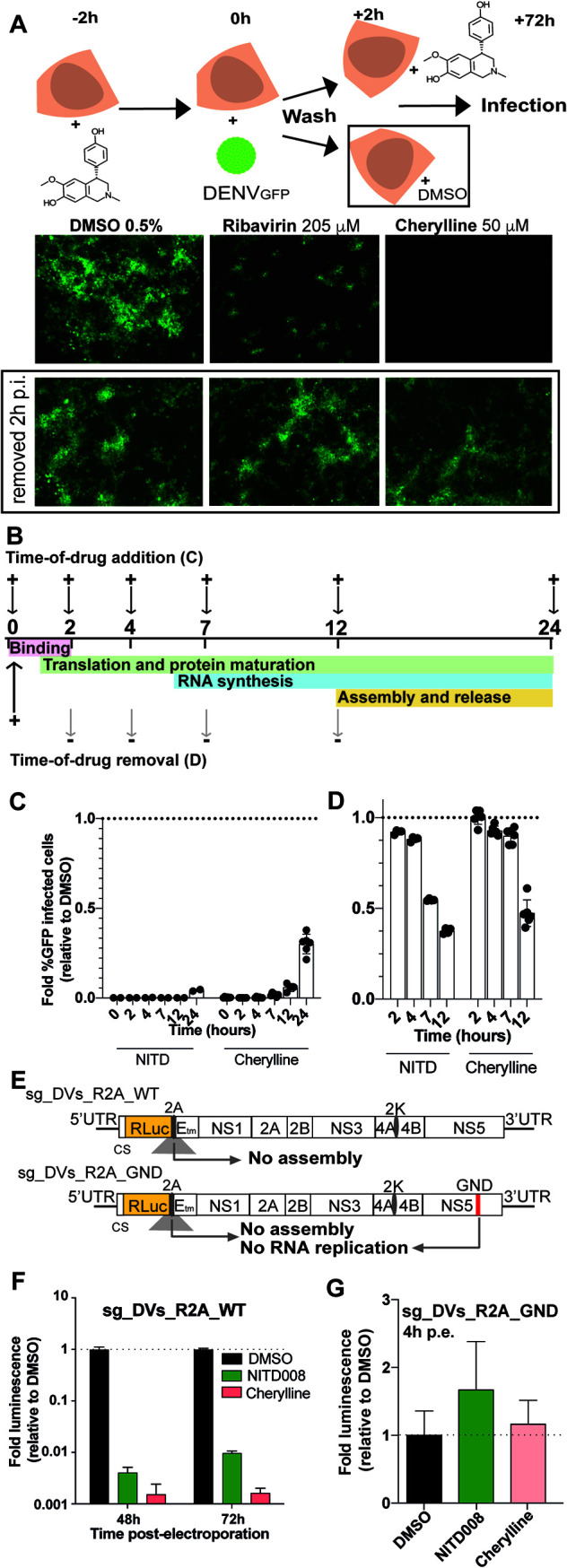

Timing of infection can be precisely associated with viral steps (Fig. 5A and B). Binding and virus entry occur during the first 2 h of viral addition (37). First, cells were treated with alkaloids 2 h prior to infection. We compared infection levels in cells with continuous treatment versus cells in which cherylline was removed 2 hpi (Fig. 5A). DMSO was used as a negative control. The guanosine analogue ribavirin was added as a positive control. Its removal 2 hpi did not impact viral replication to levels comparable to DMSO treatment, suggesting that cherylline targets a viral process occurring after that time point (Fig. 5A). Similarly, cherylline removal 2 hpi restored virus replication completely (Fig. 5A), as did removal of hippadine, flexinine, gigantellinine, sanguinine, and crinine (Fig. S3B). Restoration of infection upon removal confirmed that cherylline is not virucidal and that it inhibits a step downstream viral entry. Following viral endocytosis, initiation of translation of viral RNA and protein maturation begins as early as 1 hpi. RNA synthesis follows 6 hpi, and virion assembly, maturation, and exocytosis arise from 12 hpi. We tested the impact of cherylline addition at 0, 2, 4, 7, 12, and 24 hpi on the percentage of DENVGFP-infected Huh7 cells 72 hpi. As expected, the RNA synthesis inhibitor NITD008 abrogated GFP expression when added at 0, 2, 4, 7, or 12 hpi, prior to or during RNA synthesis (Fig. 5C). Low levels of infection rose when NITD008 was added at 24 hpi, confirming its activity at prior timing of the DENV life cycle, during RNA replication. Cherylline entirely blocked viral replication when added between 0 and 7hpi (Fig. 5C), supporting the idea that it acts at a postentry step of the viral cycle that occurs from/after 7 hpi. At 12 hpi, some cherylline antiviral activity was lost, suggesting that it optimally acts before that time of the life cycle. When added at 24 hpi, cherylline lost one-third of its inhibitory potential, consistent with an activity during the first infection. From our previous experiment (Fig. 5B), we excluded an effect on virion infectivity and viral entry, while these results suggest that cherylline possibly targets either translation, protein maturation, or RNA replication.

FIG 5.

Cherylline blocks DENV replication during RNA synthesis. (A) Infectivity of DENV in Huh7 cells continuously treated with cherylline compared to cells treated only for 2 hpi. DMSO was used as a negative control, and ribavirin as a positive antiviral control. Representative pictures taken at ×5 with an inverted microscope system are shown. (B) Schematic explanation of time-of-drug-addition and -removal rationale. +, addition of compound; –, removal. (C) Time of drug addition. (D) Time of drug removal. For panels C and D, DENVGFP was used at an MOI of 0.1; DMSO was used as a negative control, and the fold infectivity relative to the control was calculated; 1-fold means that the level of infection is the same as control. NITD008 (NITD) was used at 10 μΜ as a positive antiviral control targeting RNA synthesis. Cherylline was used at 50 μΜ. The impact of addition and removal of NITD and cherylline at 0, 2, 4, 7, 12, and 24 hpi on the percentage of DENVGFP-infected Huh7 cells was monitored by flow cytometry at 72 hpi. Experiments was performed in triplicates twice. Means with the standard error of the mean (SEM) are shown. (E) Schematic representation of subgenomic replicon sg-DVs_R2A_WT and subgenome sg-DVs_R2A_GND used in panels F and G. Sgs were transfected into Huh7.5 cells, which were then treated with DMSO, NITD008 (5 μΜ), or cherylline (50 μΜ) at the indicated time. (F) Luciferase levels were quantified at 48 and 72 h postelectroporation (hpe) with sg_DVs_R2A_WT and normalized over levels detected in DMSO-treated cells. (G) Luciferase levels were quantified at 4 hpe with RdRp-deficient sg_DVs_R2A_GND and normalized over levels in cells treated with DMSO.

Next, cherylline was added to the cells at the time of infection and then removed at each indicated time point (Fig. 5C and D). After removal of compounds, successfully produced DENV infectious particles replicate further until the time of analysis, amplifying overall infection levels. As expected, the effect of the NS5 inhibitor NITD008 was lost when the drug was removed at 2 and 4 hpi, before RNA synthesis initiation. The continuing presence of the drug until 7 hpi was necessary to its the antiviral activity. Cherylline-dependent inhibition of viral replication was lost when the AA was removed at 2, 4, or 7 hpi, while its presence for the first 12 h of the viral life cycle successfully impaired DENV replication. Similar kinetics of inhibition were observed for the other AAs tested (Fig. S4D and E). Altogether, these results indicate that cherylline acts during the RNA synthesis of the DENV life cycle. This is further supported by the fact the profile of cherylline inhibition kinetics closely mirrors that of NITD008, a potent flaviviral polymerase inhibitor.

We next challenged this mode-of-action model in an experimental setup in which the viral RNA genomes replicate without the entry and assembly steps. We took advantage of DENV subgenomic (sg) replicons (sg-DVs-R2A WT) and RNA genomes that are defective in RNA replication (sg-DVs-R2A GND, mutated GDD motif in NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase [RdRp]) (Fig. 5E). None of these genomes express structural proteins in transfected cells; hence, no viral particles are produced, and virus release or entry does not occur. Sg-DVs-R2A WT RNA replicates and is translated like the WT full-length genome; luciferase emission is directly proportional to the efficacy of viral RNA replication and translation. In vitro transcribed sg-DVs-R2A WT RNA was transfected into Huh7.5 cells and treated with DMSO, NITD008, or cherylline. At 48 to 72 h postelectroporation (hpe), both compounds were efficient in blocking viral RNA replication (3 log10 reduction of relative light units [RLU]) during steps that occurred after entry and before release (Fig. 5F; S4C). In contrast, sg-DVs-R2A GND does not replicate (Fig. S4F), and hence, luciferase activity 4 hpe reflects the efficacy of DENV RNA translation (Fig. 5E). Transfection using the RdRp-deficient replicon led to a very different profile. In control DMSO-treated cells, luciferase luminescence was high at 4 hpe and waned significantly at 24 h, in accordance with the absence of replication of this system (Fig. S4G). Cherylline, like NITD008, had no effect on the luminescence of this genome at 4 hpe, demonstrating that they do not interfere with protein synthesis (Fig. 5G). Altogether, these results unambiguously demonstrate that cherylline disrupts the RNA synthesis step of the DENV life cycle and not its infectivity, entry, and translation.

In silico reverse screening of cherylline targets.

Cherylline has been poorly studied, and its cellular and viral targets are unknown. We used in silico algorithms to get more insight into cherylline’s possible mode of action. Shape- and pharmacophore-based reverse screening with PharmMapper, ChemMapper, SwissSimilarity, and SwissTarget did not uncover any viral protein as hits, indicating that cherylline is not homologous to any currently known viral inhibitors included in the databases that were screened. Several human proteins, such as dopamine and estrogen receptors, as well as neurotransmitter transporters, and cell division protein kinase 5 were predicted to interact with cherylline (Tables S1 and S2), suggesting that it might target cellular proteins implicated in the viral life cycle. Interestingly, estrogen and neurotransmitter-interacting proteins were most often uncovered as hits. Finally, we used SwissADME to calculate ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) and Lipinski’s parameters of cherylline (Table S3) and other AAs. Cherylline structure respects the five rules of Lipinski with a molecular weight of <500 Da, a liposolubility (octanol/water) logP of <4.15, fewer than 10 electron acceptors and fewer than 5 donors, and a biodisponibility score of 0.55. This prediction suggests that cherylline possesses the chemical properties that are compatible with therapeutic usage in humans.

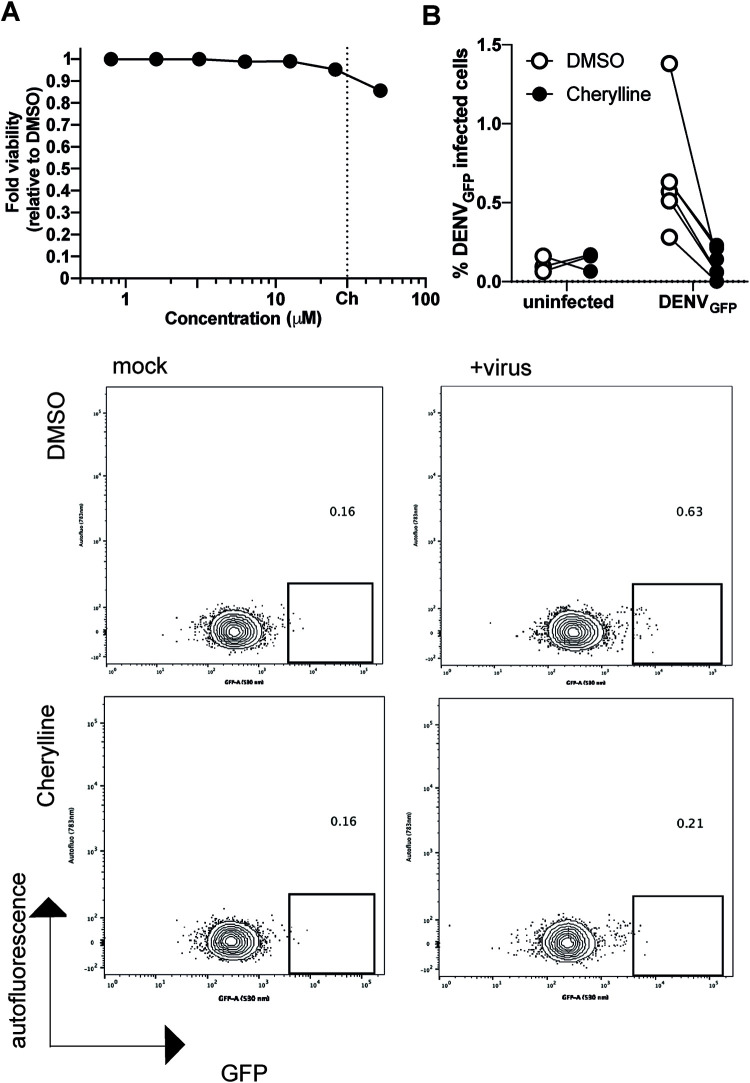

Cherylline inhibits DENV infection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Finally, we wanted to validate cherylline antiflaviviral potential in a human primary cell model relevant to dengue disease, namely, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (38). PBMCs were infected with DENVGFP particles which were preincubated with a panflaviviral antienvelope antibody to increase infection levels in monocytes through antibody-dependent enhancement (39, 40). Infected PBMCs were then treated for 72 h with 30 μM cherylline, a concentration that was not toxic for these primary cells (Fig. 6A). Of note, NITD008 was excluded from further analysis because it was cytotoxic in PBMCs. The percentage of infected cells (GFP-positive cells) was determined using flow cytometry (Fig. 6B). In DMSO-treated control cells, GFP intensity was low but readily detectable, and a median of 0.6% GFP+ cells were productively infected with DENVGFP. Cherylline treatment led to a 5.3-fold decrease in the percentage of GFP+ cells (P = 0.0011, Mann-Whitney test), with a median of 0.1% GFP+ cells, similar to background levels (Fig. 6C). These results validate the anti-DENV potential of cherylline in human primary blood cells, a target of DENV during pathogenesis.

FIG 6.

Cytotoxicity and antiviral effects of cherylline in PBMCs. (A) The cytotoxicity of antiviral concentrations of cherylline in PBMCs was measured by ATP production and normalized over DMSO at 48 h posttreatment. Means with SEM are shown. Dotted lines represent the concentration used in the antiviral assay. Ch, cherylline. (B) Antiviral activity of cherylline in PBMCs. PBMCs were infected with DENVGFP preincubated with anti-Envelope antibody 4G2 at an MOI of 2, treated with cherylline (30 μM) or DMSO (0.05%), and analyzed 72 hpi by flow cytometry. The experiment was performed in triplicates (uninfected) and six-plicates (infected). Representative plots are shown.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we showed that several alkaloids from C. jagus display cytotoxicity and anticholinesterase activity (24). Here, we uncovered that crude alkaloid extract from Crinum jagus inhibited DENV infection in cellulo. We further investigated the antiviral potential of the 9 alkaloids of crinine, lycorine, galanthamine, and cherylline ring types isolated from this plant. While lycorine’s antiviral activity is well known, the potential of other AAs has not been previously characterized. Here, we investigated their activity on DENV and ZIKV and HIV-1 infection.

First, we discovered that in addition to lycorine, C. jagus extract contains another compound that efficiently blocks DENV, namely, cherylline. Other AAs isolated from C. jagus displayed weak activity at high concentrations (gigantelline, gigantellinine, and crinine- and galanthamine-type structures) or were highly cytotoxic (hippadine).

We confirmed the anti-DENV activity of cherylline, measuring the inhibition of viral replication through modulation of the Rluc reporter gene expression. Because of the genetic proximity between DENV and ZIKV proteins, we tested cherylline anti-ZIKV activity and determined that it also efficiently blocked ZIKV replication. Then, to gain understanding of the specificity of cherylline’s antiviral activity, we tested its effect on HIV-1 using a replication-deficient virus pseudotyped with a vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G) envelope. Thus, if entry, assembly, or release were targeted by tested compounds, this would be missed by the current assay. We did not detect any antiretroviral activity from cherylline or from any of the AAs tested against this virus. Lycorine was reported to inhibit HIV-1 infection in some studies (41, 42), while others have demonstrated that it was a very poor inhibitor of HIV-1 reverse transcription (RT) (43) or that it did not inhibit HIV-1 (26). Its cytotoxicity could be responsible for these discrepancies, as even at antiviral concentrations (1 to 5 μM), lycorine treatment nonspecifically increases the detected antiviral activity because of the progressive depletion of viable permissive cells. Nonetheless, our results unequivocally show that HIV-1 life cycle steps between entry and release are not targeted by the studied AAs in THP-1 cells. Interestingly, a study published in 1989 reported that cherylline derivatives had no significant effect against the DNA virus herpes simplex virus (44). Altogether, this suggests that cherylline antiviral activity exhibits some selectivity to flaviviruses.

Then, we assessed the effect of cherylline on the replication of WT strains of ZIKV and DENV2. Cherylline dampened viral titers from the pathogenic ZIKV H/PF/2013 strain about a 100-fold. It diminished replication of WT ZIKV MR766 and WT DENV2 16881s 8- and 17-fold, respectively, to very low levels compared to the control. These experiments were performed in the highly permissive Huh7.5 and Vero cell lines, which are more permissive than Huh7 cells to flaviviral replication. Hippadine hindered French Polynesian ZIKV replication, albeit at concentrations that displayed cytotoxicity. It had little effect on the propagation of other strains of ZIKV and on WT DENV-2. Gigantellinine and flexinine had little effect on all three viral strains.

Having established that cherylline inhibited flavivirus infection, we investigated the life cycle steps that could be targeted. We removed the drug 2 hpi, which abolished its antiviral effect, showing that cherylline was not viricidal and that it did not prevent binding or viral entry into cells. We pursued identification of the viral step that was targeted using time-of-drug-addition and -removal assays. Cherylline treatment did severely impede viral replication when added between 0 and 7 hpi, whereas its antiviral potency was lost when removed at 2, 4, or 7 hpi and recovered at 12 hpi. Thus, its presence between 7 and 12 hpi is required to successfully impair infection, suggesting that it acts at a postentry step, possibly during RNA synthesis. By using subgenomic replicons and replication-deficient genomes, we confirmed that cherylline did inhibit the RNA replication step of the DENV life cycle but did not target infectivity, entry, or translation. We used a hygromycin-resistant replicon to attempt to isolate escape mutants and identify cherylline’s potential viral target. Unfortunately, cells containing resistant DENV subgenomes were not generated following a continuous treatment of 30 days. This does not exclude a direct effect of cherylline on viral enzymes such as RdRp, as similar observations were made using the NITD008 nucleoside analog (35). Instead, these results support the finding that cherylline exhibits a strong barrier to resistance.

The replication complex of DENV virus in the endoplasmic reticulum is composed of its nonstructural proteins in interaction with several cellular proteins, all playing a key role in viral replication (45–48). Lycorine also inhibits the RNA replication step, but the exact mechanism is not known. Chen et al. showed that high concentrations of lycorine (100 μM) inhibited 80% of ZIKV NS5 RdRp activity in vitro (28), but this concentration is 100-fold higher than what is tolerated by cells. Others reported that lycorine had no effect on West Nile virus NS5, but rather, that its activity was dependent on the valine at the 9th position of the 2K peptide (27). The 2K peptide is part of the replication complex, playing a key role in polyprotein maturation and topology as well as in replication organelle biogenesis (49–52). Lycorine and cherylline structures contain distinct ring types. Although AAs are known for their pleiotropic effects, cherylline does not display the same broad antiviral spectrum as lycorine. Cherylline targeted multiple proteins to achieve its antiviral activity. It interacted with human proteins rather than viral proteins, such as dopamine and estrogen receptors, as predicted by in silico reverse screening. Indeed, the dopamine receptor D1 and D4 antagonists prochlorperazine and dihydrobenzothiepines have been described to inhibit DENV replication (53, 54), but they target early steps of DENV replication, i.e., viral binding and entry, in contrast to cherylline. Recently, estrogen receptor modulators were also identified as flavivirus inhibitors, independently of the estrogen receptor itself. Cyclofenil, which interacts with NS1, and raloxifene both target RNA replication and polyprotein translation by an unknown mechanism (55, 56). Cyclofenil also impacted viral assembly/maturation (56). Although these inhibitors do not share the same mode of action as cherylline, this emphasizes that many cellular or viral proteins could be targeted by the AA. In any case, further investigations are required to uncover the target, which will enable interaction studies and, potentially, optimization and identification of resistance mechanism.

Despite their strong similitude in structure with cherylline (Fig. 2A), gigantelline and gigantellinine effects were much poorer. These disparities are probably due to distinct functionalization or stereochemistry of their shared carbon skeleton. As cherylline and gigantellinine hold the same stereochemistry, the distinction between the two compounds associated with the reduction of antiviral potential, rather, lies on the presence of a further hydroxyl group at C-5′ and/or methyoxylation of the hydroxyl group at C-4′ in the C-ring of gigantellinine. In the case of gigantelline, the further loss of activity is associated with a singular stereochemistry of the junction between B/C rings and/or to the methoxylation of the hydroxyl group at C-7 of its A ring. Palmatine, another isoquinoline alkaloid, was shown to display antiflaviviral potential, although higher concentrations were required to inhibit DENV with higher cytotoxicity (EC50, 26.4 μM and CC50, 1,031 μM) (57). Plamatine’s structure is distinct from cherylline’s in several aspects, highlighting that the para-substituted phenol ring could play a role in the observed differences in antiviral activity. Thus, our study provides some insight into cherylline structural determinants required for its antiflaviviral activity, which will have to be taken into consideration for chemical optimization in future structure-activity relationship studies.

Finally, we validated cherylline antiviral activity in human primary blood cells that are targeted by DENV in the natural course of infection in vivo. PBMCs are generally poorly permissive in vitro (58, 59), but they include monocytes, which are believed to be important targets of DENV and to contribute to viral dissemination in patients (60, 61). Cherylline was not cytotoxic to PBMCs and efficiently inhibited DENVGFP infection in these cells. Importantly, lycorine has been successfully used in mice to fight ZIKV (28), highlighting that AAs may provide therapeutic gain. Although cherylline can be extracted from several Amaryllidaceae species, mostly from the Crinum genus (62–64), it is considered a rare alkaloid. Fortunately, cherylline chemical synthesis has been successfully performed through several methods (65–67), as reviewed in reference 68, providing an alternative method of production. AA’s biosynthesis pathway is beginning to be uncovered (15); once the enzymes responsible for cherylline synthesis are confirmed, exogenous introduction of encoding genes into yeasts or microalgae will be an interesting strategy to produce AAs.

Conclusion.

Until now, cherylline was mostly known for its moderate antiacetylcholinesterase activity and has never been associated with antiflaviviral activity before, nor have any derivatives. We show that most AAs from Crinum jagus display a low to moderate effect against DENV. Our study shows that cherylline inhibits replication of both DENV and ZIKV. Although the EC50 obtained for cherylline was quite high, its low cytotoxicity in PBMCs makes it an interesting lead compound to fight DENV and ZIKV and could pave the way to new therapeutic strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crinum jagus crude extract and GC-MS analysis.

Bulbs of C. jagus (giganteum) were collected in Senegal in the Montrolland district (14°55′56.22″N and 16°59′38.62″W) in 2018 and taxonomically identified by a senior scientist from the Herbarium of IFAN of the University Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar. Alkaloids were extracted from dried bulbs of C. jagus using the method described in reference 69. High-performance liquid chromatography with a diode-array detector (HPLC-DAD) and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) confirmed the presence of alkaloids in the extract. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis was performed using the method described in reference 70. Alkaloids were identified by comparison with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST 05) database based on matching mass spectra. The total ion current (TIC) percentage provided in Table 2 was connotated with the proportion of each compound in the extract. The area under the GC-MS peaks depends both on the concentration of the related compounds and on the intensity of their mass spectrum.

TABLE 2.

Alkaloids identified by GC-MS in C. jagus bulb extracta

| Alkaloid | [M+] | BP | RT (min) | CJ (%) | Identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vittatine/crinine | 271 | 271 | 21.871 | 24.418 | NIST 05 Database |

| Cherylline | 285 | 242 | 23.173 | 9.413 | NIST 05 Database |

| Lycorine | 287 | 226 | 25.871 | 19.68 | NIST 05 Database |

| Unidentified | 299 | 225 | 23.531 | 31.422 | NA |

| Unidentified | 315 | 241 | 25.030 | 15.68 | NA |

Values are expressed as percentages of total ion current (TIC) for the relative quantitative CJ. BP, base peak; RT, retention time (in minutes); CJ, C. jagus; NA, not applicable.

Amaryllidaceae alkaloids.

Lycorine, hippadine, sanguinine, crinine, gigancrinine, flexinine, cherylline, gigantelline, and gigantellinine were isolated from C. jagus as reported in reference 24. Their purity, >98%, was ascertained by 1H NMR and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC/MS) spectrometry. Each AA was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 100 mM as a stock solution and stored at –20°C until further usage. At the time of use, they were diluted in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium high glucose (DMEM) or RPMI medium to the desired concentration. DMSO was used as a negative control, whereas guanosine analogue ribavirin and flaviviral NS5 inhibitor NITD008 (Tocris Bioscience) were used as positive antiviral controls.

Cell culture.

The human hepatocarcinoma Huh7 cell line was kindly provided by Hugo Soudeyns. Murine LL171 reporter cells (71), Crandell-Rees Feline Kidney (CRFK), and Huh7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS) solution (all from Wisent, Inc., Canada). Hepatocarcinoma RIG-I-deficient Huh7.5 (a kind gift from Patrick Labonté), and Vero E6 (kindly shared by Tom Hobman) cells were cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) containing 10% FBS, 1% PS, and 1% nonessential amino acids (Thermo Fisher). Human embryonic kidney HEK293T and human monocytic cell line THP-1 were grown in RPMI (Wisent) with 10% FBS and 1% PS. Frozen human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained using Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved consent forms and protocols (Stem Cell Technologies). They were thawed in 20% FBS containing RPMI prewarmed at 37°C, washed twice, and incubated for 6 h. Medium was replaced by RPMI with 10% FBS and 1% PS before cytotoxic and antiviral assays. All cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cytoxicity assay.

Cytotoxicity properties were titrated by metabolism monitoring using the XTT [2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide] assay kit (Roche, Millipore Sigma), as described before (24). Briefly, Huh7 cells were seeded at 10 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates. Concentrations of alkaloid bulb extract ranging from 0.019 to 2.5 μg/ml were added the next day. After 72 h of incubation, medium was replaced by phenol-free DMEM (Wisent) containing 0.3 mg/ml XTT, and cells were incubated for 4 h. Absorbance was measured at 450nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Synergy H1, Biotek). Treatment conditions with 0.5% DMSO were used as the reference control. The percentage of cell viability was calculated at each concentration.

Where indicated for Huh7.5 and Vero E6 cells and PBMCs, cell viability was measured by monitoring of cellular ATP levels using the Cell-Titer GLO assay kit (Promega). Briefly, 10× 103 to 20 × 103 cells in 50 to 100 μl were seeded in 48-well or 96-well plates and cultured overnight. AAs were added at the designated concentrations for 24 or 48 h, as specified in the text. Then, 50 to 100 μl of room temperature Cell-Titer GLO reagent was added in each well to room temperature-equilibrated cell plates. Plates were rocked for 2 min and rested for 10 min, and the luminescence signal was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek Synergy H1 or Tecan Spark multimode microplate reader). Viability was expressed as a fold change calculated using the value of DMSO-treated cells at each concentration; for each AA and CC50, values were determined.

Preparation of flaviviral genomes.

Plasmids for DENV or ZIKV vectors which encode GFP (pFK-DVs-G2A for DENVGFP), Renilla luciferase (pFK-DVs-R2A, serotype 2, strain 16681 for DENVR2A; pFL-ZIKV-R2A strain FSS13025 for ZIKVR2A) reporter genomes, wild-type (WT) DENV (pFK-DVs; 16681), subgenomic (sg) replication-deficient NS5 mutant (sg-DVs-R2A-GND), and WT (sg-DVs-R2A-WT) subgenomic replicon systems were all obtained from Ralf Bartenschlager and Pei-Yong Shi. Plasmids were linearized with XbaI (DENV) or ClaI (ZIKV) and purified, and 1 μg was in vitro transcribed using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 or SP6 transcription kit (Invitrogen). The resulting RNA quality and concentration were assessed by migration on a 0.8% agarose gel and Nanodrop spectrometry (Thermo Scientific), respectively.

Production of DENV and ZIKV stocks.

Subconfluent trypsinized Vero E6 cells were washed once and resuspended in cytomix buffer (120 mM KCl, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.6], freshly supplemented with 2 mM ATP and 5 mM glutathione) at a density 1.5 × 107 cells/ml, as described in reference 45. Then, 10 μg of in vitro-transcribed viral RNA genomes (from pFK-DVs, pFK-DVs-R2A, pFK-DVs-GFP, pFL-ZIKV, and pFL-ZIKV-R2A) were mixed with 400 μl of cells, transferred into an electroporation cuvette (Bio-Rad; 0.4-cm gap width), and pulsed once with a GenePulser Xcell instrument (Bio-Rad) at 975 μF and 270 V. Cells were immediately transferred to prewarmed complete DMEM and seeded. Culture medium was changed 24 h postelectroporation (hpe). Virus-containing cell culture supernatants were harvested 4 to 8- days postelectroporation, concomitantly with the appearance of cytopathic effect (CPE). Virus stocks were filtered through 0.45-μm syringe filters and supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and aliquots were stored at –80°C until use. ZIKV H/PF/2013 (French Polynesia) and ZIKV MR766 (Uganda) virus stocks were obtained from the European Virus Archive Global (EVAg). ZIKV stocks (ZIKV H/PF/2013 and ZIKV MR766) were amplified and produced in Vero E6 cells. Plaque assays (described below) were used to determine the infectious titers of the virus stocks (72).

AA anti-ZIKV and -DENV activity.

Briefly, Huh7 cells were seeded at 15 × 103 cells per well in 48-well plates and cultured for 16 h. Cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of C. jagus bulb crude extract or AAs for 2 h and infected with DENVGFP at an MOI of 0.1 to 0.3, depending on the assay, and further incubated for 72 h at 37°C. PBMCs were infected with DENVGFP (MOI, 2) preincubated with the panflaviviral antienvelope 4G2 antibody (clone D1-4G2-4-15; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 4°C to enhance infection through antibody-dependent enhancement (73, 74). Cells were washed 24 hpi, and further incubated for 48 h. GFP signal of infected cells was visualized on an Axio Observer microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) or measured on a flow cytometer (FC500 MPL cytometer or a BD FACSMelody; BD Lifesciences-Biosciences) and analyzed with FCS express 6 and FlowJo software (BD).

To determine the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50), Huh7.5 cells were plated in 10-mm petri dishes and infected with DENVR2A and ZIKVR2A (MOI, 0.005). Virus inoculum was removed 2 hpi, and cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, and plated in a 96-well plate with various concentrations of AAs. After 48 h, luciferase production was monitored as described below.

Subgenome RNAs (sg-DVs-R2A-GND, sg-DVs-R2A-WT, and sg-DVs-R2H) were directly transfected into Huh7.5 cells by electroporation, and luminescence was measured at the indicated time points following the procedures described below.

Luciferase detection.

Luminescence emitted from virus-encoded Renilla luciferase (Rluc) was measured to monitor viral replication (DENV-R2A, sg-DVs-R2A-WT, and ZIKV-R2A) or viral protein translation (sg-DVs-R2A-GND). Infected cells were lysed in 100 μl lysis buffer (0.1% Triton X-100, 25 mM glycylglycine [pH 7.8], 15 mM MgSO4, 4 mM EGTA [pH 8], and 1 mM DTT). Rluc assays was performed by injecting 150 μl of assay buffer (25 mM glycylglycine [pH 7.8], 15 mM MgSO4, 4 mM EGTA [pH 8], and 15 mM K2PO4 [pH7.8]) and coelenterazine (1.43 μM Prolume) to 30 μl of the lysate, as described in reference 75. Luminescence was measured in a Spark multimode microplate reader (Tecan).

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR.

TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich) (for experiments using DENVGFP) or an RNeasy kit (Qiagen; for experiments using WT DENV and ZIKV) were used to extract total RNA from infected and control cells at 12 and 24 h postinfection according to the manufacturers protocol. Glycogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added during the extraction. Cell lines, virus types, and MOI are specified in the figure legends for each experiment. Viral RNA levels were assessed through a one-step reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) protocol with a One Step TB Green PrimeScript RT-PCR kit II (perfect real time) (TaKaRa Bio, Inc.) in the case of DENVGFP. Amplification and fluorescence detection were performed using 2 μl template (250 to 500 ng) and 400 nM forward and reverse primers in 20 μl final volume on an Mx3000 real-time PCR system (Agilent). A reverse transcription step was performed at 42°C for 5 min and 95°C for 10 sec, and PCR was performed for 40 cycles at 95°C and 60°C for 34 s, followed by a dissociation curve from 60 to 95°C. Relative viral RNA abundance was normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels. The threshold cycle (CT) was determined using MxPro software (Agilent). In the case of WT viruses, reverse transcription was performed with 800-ng template RNA using SuperScript IV VILO master mix with an ezDNase enzyme kit (Invitrogen). Amplification and fluorescence detection were performed using PowerUP SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems), 5 μl cDNA, and 300 nM forward and reverse primers in 10 μl final volume on a LightCycler 96 device (Roche). A reverse transcription step was performed at 25°C for 10 min, 50°C for 10 min, and 85°C for 5 min. qPCR was performed at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Primers sequences were as follow: (i) for DENV 16681s, 5′-GCCCTTCTGTTCACACCATT-3′ and 5′-CCACATTTGGGCGTAAGACT-3′; (ii) for ZIKV H/PF/2013, 5′-AGATGAACTGATGGCCGGGC-3′ and 5′-AGGTCCCTTCTGTGGAAATA-3′; and (iii) for GAPDH, 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ and 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′. Relative expression was calculated using the ΔΔCT method with GAPDH for normalization and normalized on background levels in noninfected cells.

DENV and ZIKV titration by plaque assay.

Huh7.5 cells were infected with DENV 16881s, ZIKV H/PF/2013, or ZIKV MR766 (MOI, 0.1) or left uninfected. Viral inoculum was removed 2 hpi, and cells were treated with AAs, NITD008, or DMSO (vehicle). Supernatants were harvested 2 days pi, and PFU were determined by plaque assay on VeroE6 cells. Cells incubated overnight (2 × 105 cells/well in 24-well plates) were infected with 10-fold serially diluted virus-containing supernatants for 2 h at 37°C. Inoculum was then replaced with MEM (Life Technologies) containing 1.5% carboxymethylcellulose (Millipore-Sigma). ZIKV- and DENV-infected cells were incubated for 5 and 7 days, respectively. One volume of 10% formaldehyde was added to the cells for fixation. Two hours later, cells were washed with tap water and stained with a 1% crystal violet/10% ethanol solution for 30 min. Wells were rinsed with tap water, and the number of plaques were counted to calculate virus titers.

Time-of-drug-addition and -removal assays.

Huh7 cells (1.5 × 104 per well) were seeded in 48-well plates and infected with DENVGFP at an MOI of 0.15. For the time-of-drug-addition assay, at the time of infection, AAs were added in wells corresponding to 0 h. At 2 hpi, viral inoculum was removed from every well, and AAs were added back to wells corresponding to 0 h and 2 h. At 4, 7, 12, and 24 hpi, AAs or DMSO diluted in DMEM was added to the appropriate wells. After 72 h, cells were trypsinized and fixed in 4% formaldehyde to measure the percentage of infected cells on an FC500 MPL cytometer. Alternatively, pictures of Hoechst 33342-stained cells were acquired on an Axio Observer microscope. All assays were performed in triplicate.

For the time-of-drug-removal assay, Huh7 cells were seeded in 48-wells plates (1.5 × 104 cells per well), infected with DENVGFP at an MOI of 0.15, and treated with medium containing AAs at the indicated concentrations at the time of infection. At 2 hpi, plates were washed, and medium was replaced to remove remaining viruses in the supernatant. AAs were added back to all wells, except the ones corresponding to 2 h of treatment, in which fresh medium exclusive of any AA was added. Accordingly, after 4, 7, and 12 h of infection, the supernatant was replaced by fresh medium in corresponding wells. After 72 h of incubation, results were acquired as for the time-of-drug-addition assay. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Production of VSV-G-pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 vectors.

pNL4-3GFPΔEnvΔNef is replication-incompetent due to a deletion that produces a frameshift in env, and nef is replaced by gfp (green fluorescent protein) as described in reference 76. pNL4-3GFPΔEnvΔNef and pMD.G (a plasmid encoding vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein [VSV-G]) were prepared from bacterial stocks using the Qiagen MidiPrep kit. To produce HIV-1GFP vectors, plasmids were cotransfected into 90% confluent HEK293T cells in 10-cm culture dishes using polyethylenimine (PEI; Polysciences, Niles, IL) as described in reference 77. Medium was changed 6 to 16 h posttransfection. Supernatants containing HIV-1GFP were harvested 24 h later, centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 rpm, 0.45-μm-filtered, and stored at –80°C. The MOI was assessed by measuring the infectivity of serially diluted vector preparation in CRFK cells.

HIV-1GFP infectivity assay.

AA antiretroviral activity was evaluated using HIV-1GFP in THP-1 cells. Briefly, THP-1 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells per well in 96 well-plates and incubated overnight. Cells were pretreated with two concentrations of AAs for 2 h and then infected with HIVGFP at an MOI of 1. After 72 h, the percentage of infected cells was measured using an FC500 MPL cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., California) and analyzed using FCS Express 6 software (De Novo Software, California). DMSO and nevirapine (Sigma-Aldrich, Canada) were used as a negative and a positive control, respectively. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Type I IFN activation assay.

In vitro type I IFN activation was measured in LL171 cells using the luciferase assay system kit (Promega). Briefly, 200 μl LL171 reporter cells (L929 cells expressing an IFN stimulated response element [ISRE]-luciferase [78]) were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates and cultured for 16 h. Medium was replaced with DMEM containing cherylline for 24 h. Supernatant was removed, cells were rinsed with PBS, and lysis buffer was added (luciferase assay reagent; Promega). Then, cells were scraped and transferred into opaque 96-well plates. LAR (luciferase assay reagent; Promega) was added to each well, and luminescence was measured at 480 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Synergy H1). 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA, 20 μg/ml) was used as a positive control. All assays were performed in triplicate.

In silico characterization of cherylline.

SwissSimilarity was used to screen analogous compounds in the PDB database (79). SwissTargetPrediction (80), ChemMapper (81), and PharmMapper (82) were used for the virtual reverse screening of cherylline’s possible targets. SwissADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) was used to predict the ADME properties of the cherylline drug (83).

Statistical analyses.

Graphs and statistical analyses (EC50, CC50) were performed with GraphPad Prism 7 software. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used, and P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Celine Van Themsche, Maria-Grazia Martinoli, and Carlos Reyes Moreno for generously sharing their laboratory equipment and material. In addition, we thank Patrick Lagüe for sharing his expertise in bioinformatics. We are grateful to Pei-Yong Shi and the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCEVA) for providing the ZIKV reporter system and Ralf Bartenschlager (University of Heidelberg) for all DENV reporter constructs. We thank the European Virus Archive goes Global (EVAg) and Xavier de Lamballerie (Emergence des Pathologies Virales, Aix-Marseille University) for providing ZIKV MR766 and H/PF/2013 original stocks. We are grateful to Patrick Labonté (Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique), Tom Hobman (University of Alberta), and Anil Kumar (University of Saskatchewan) for generously providing Huh7.5 and Vero E6 cells.

We thank the Government of Senegal for awarding a scholarship to S.K. This work was funded by Canada Research Chair on Plant Specialized Metabolism award no. 950-232164 to I.D.-P. Thanks are extended to the Canadian taxpayers and to the Canadian government for supporting the Canada Research Chairs Program.

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambrechts L, Scott TW, Gubler DJ. 2010. Consequences of the expanding global distribution of Aedes albopictus for dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e646. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dwivedi VD, Tripathi IP, Tripathi RC, Bharadwaj S, Mishra SK. 2017. Genomics, proteomics and evolution of dengue virus. Brief Funct Genom 16:217–227. 10.1093/bfgp/elw040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossmann M, Kuhn R, Zhang W, Pletnev S, Corver J, Lenches E, Jones C, Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman P, Strauss E. 2002. Structure of dengue virus: implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Acta Cryst A58:C6. 10.1107/S0108767302085343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Wilschut J, Smit JM. 2010. Dengue virus life cycle: viral and host factors modulating infectivity. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:2773–2786. 10.1007/s00018-010-0357-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quintana V, Selisko B, Brunetti J, Eydoux C, Guillemot J, Canard B, Damonte E, Julander J, Castilla V. 2020. Antiviral activity of the natural alkaloid anisomycin against dengue and Zika viruses. Antiviral Res 176:104749. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gubler DJ. 1998. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 11:480–496. 10.1128/CMR.11.3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Factsheets WWHO. 2017. Dengue and severe dengue. https://apps.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/index.html.

- 8.Indu P, Arunagirinathan N, Rameshkumar MR, Sangeetha K, Divyadarshini A, Rajarajan S. 2020. Antiviral activity of astragaloside II, astragaloside III and astragaloside IV compounds against dengue virus: computational docking and in vitro studies. Microb Pathog 152:104563. 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dieng I, Cunha M.dP, Diagne MM, Sembène PM, Zanotto P. M d A, Faye O, Faye O, Sall AA. 2021. Origin and spread of the dengue virus type 1, genotype V in Senegal, 2015–2019. Viruses 13:57. 10.3390/v13010057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Powers AM, Honein MA. 2016. Zika virus. N Engl J Med 374:1552–1563. 10.1056/NEJMra1602113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plourde AR, Bloch EM. 2016. A literature review of Zika virus. Emerg Infect Dis 22:1185–1192. 10.3201/eid2207.151990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Check Hayden E. 2016. Zika highlights role of controversial fetal-tissue research. Nature News 532:16. 10.1038/nature.2016.19655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khetarpal N, Khanna I. 2016. Dengue fever: causes, complications, and vaccine strategies. J Immunology Res 2016:1–14. 10.1155/2016/6803098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong H, Zhang B, Shi P-Y. 2008. Flavivirus methyltransferase: a novel antiviral target. Antiviral Res 80:1–10. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desgagné-Penix I. 2021. Biosynthesis of alkaloids in Amaryllidaceae plants: a review. Phytochem Rev 20:409–431. 10.1007/s11101-020-09678-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotchandani T, Desgagne-Penix I. 2017. Heterocyclic Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: biosynthesis and pharmacological applications. Curr Top Med Chem 17:418–427. 10.2174/1568026616666160824104052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ka S, Koirala M, Mérindol N, Desgagné-Penix I. 2020. Biosynthesis and biological activities of newly discovered Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Molecules 25:4901. 10.3390/molecules25214901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cimmino A, Masi M, Evidente M, Superchi S, Evidente A. 2017. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: absolute configuration and biological activity. Chirality 29:486–499. 10.1002/chir.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding Y, Qu D, Zhang K-M, Cang X-X, Kou Z-N, Xiao W, Zhu J-B. 2017. Phytochemical and biological investigations of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: a review. J Asian Nat Prod Res 19:53–100. 10.1080/10286020.2016.1198332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duri ZJ, Scovill JP, Huggins JW. 1994. Activity of a methanolic extract of Zimbabwean Crinum macowanii against exotic RNA viruses in vitro. Phytother Res 8:121–122. 10.1002/ptr.2650080217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapu S, Ngwai Y, Kayode O, Akah P, Wambebe C, Gamaniel K. 2001. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and anti-lymphocytic activities of the aqueous extract of Crinum giganteum. J Ethnopharmacol 78:7–13. 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adesanya S, Olugbade T, Odebiyl O, Aladesanmi J. 1992. Antibacterial alkaloids in Crinum jagus. Int J Pharmacognosy 30:303–307. 10.3109/13880209209054019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogbole OO, Akinleye TE, Segun PA, Faleye TC, Adeniji AJ. 2018. In vitro antiviral activity of twenty-seven medicinal plant extracts from Southwest Nigeria against three serotypes of echoviruses. J Virol 15:110. 10.1186/s12985-018-1022-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ka S, Masi M, Merindol N, Di Lecce R, Plourde MB, Seck M, Gorecki M, Pescitelli G, Desgagne-Penix I, Evidente A. 2020. Gigantelline, gigantellinine and gigancrinine, cherylline- and crinine-type alkaloids isolated from Crinum jagus with anti-acetylcholinesterase activity. Phytochemistry 175:112390. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang P, Li LF, Wang QY, Shang LQ, Shi PY, Yin Z. 2014. Anti-dengue-virus activity and structure-activity relationship studies of lycorine derivatives. ChemMedChem 9:1522–1533. 10.1002/cmdc.201300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabrielsen B, Monath TP, Huggins JW, Kefauver DF, Pettit GR, Groszek G, Hollingshead M, Kirsi JJ, Shannon WM, Schubert EM, DaRe J, Ugarkar B, Ussery MA, Phelan MJ. 1992. Antiviral (RNA) activity of selected Amaryllidaceae isoquinoline constituents and synthesis of related substances. J Nat Prod 55:1569–1581. 10.1021/np50089a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou G, Puig-Basagoiti F, Zhang B, Qing M, Chen L, Pankiewicz KW, Felczak K, Yuan Z, Shi P-Y. 2009. A single-amino acid substitution in West Nile virus 2K peptide between NS4A and NS4B confers resistance to lycorine, a flavivirus inhibitor. J Virol 384:242–252. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Lao Z, Xu J, Li Z, Long H, Li D, Lin L, Liu X, Yu L, Liu W, Li G, Wu J. 2020. Antiviral activity of lycorine against Zika virus in vivo and in vitro. J Virol 546:88–97. 10.1016/j.virol.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S-Y, Chen C, Zhang H-Q, Guo H-Y, Wang H, Wang L, Zhang X, Hua S-N, Yu J, Xiao P-G, Li R-S, Tan X. 2005. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antiviral Res 67:18–23. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y-N, Zhang Q-Y, Li X-D, Xiong J, Xiao S-Q, Wang Z, Zhang Z-R, Deng C-L, Yang X-L, Wei H-P, Yuan Z-M, Ye H-Q, Zhang B. 2020. Gemcitabine, lycorine and oxysophoridine inhibit novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in cell culture. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:1–10. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1772676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin Y-H, Min JS, Jeon S, Lee J, Kim S, Park T, Park D, Jang MS, Park CM, Song JH. 2020. Lycorine, a non-nucleoside RNA dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, as potential treatment for emerging coronavirus infections. Phytomedicine 86:153440. 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen L, Niu J, Wang C, Huang B, Wang W, Zhu N, Deng Y, Wang H, Ye F, Cen S, Tan W. 2019. High-throughput screening and identification of potent broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronaviruses. J Virol 93:e00023-19. 10.1128/JVI.00023-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischl W, Bartenschlager R. 2013. High-throughput screening using dengue virus reporter genomes. Methods Mol Biol 1030:205–219. 10.1007/978-1-62703-484-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng YQ, Zhang NN, Li CF, Tian M, Hao JN, Xie XP, Shi PY, Qin CF. 2016. Adenosine analog NITD008 is a potent inhibitor of Zika virus. Open Forum Infect Dis 3:ofw175. 10.1093/ofid/ofw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin Z, Chen YL, Schul W, Wang QY, Gu F, Duraiswamy J, Kondreddi RR, Niyomrattanakit P, Lakshminarayana SB, Goh A, Xu HY, Liu W, Liu B, Lim JY, Ng CY, Qing M, Lim CC, Yip A, Wang G, Chan WL, Tan HP, Lin K, Zhang B, Zou G, Bernard KA, Garrett C, Beltz K, Dong M, Weaver M, He H, Pichota A, Dartois V, Keller TH, Shi PY. 2009. An adenosine nucleoside inhibitor of dengue virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:20435–20439. 10.1073/pnas.0907010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCracken MK, Gromowski GD, Garver LS, Goupil BA, Walker KD, Friberg H, Currier JR, Rutvisuttinunt W, Hinton KL, Christofferson RC, Mores CN, Vanloubbeeck Y, Lorin C, Malice M-P, Thomas SJ, Jarman RG, Vaughn DW, Putnak JR, Warter L. 2020. Route of inoculation and mosquito vector exposure modulate dengue virus replication kinetics and immune responses in rhesus macaques. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14:e0008191. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang J, Zhang Y, Cao X, Fan J, Li G, Wang Q, Diao Y, Zhao Z, Luo L, Yin Z. 2012. Lycorine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced iNOS and COX-2 up-regulation in RAW264.7 cells through suppressing P38 and STATs activation and increases the survival rate of mice after LPS challenge. Int Immunopharmacol 12:249–256. 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen YL, Abdul Ghafar N, Karuna R, Fu Y, Lim SP, Schul W, Gu F, Herve M, Yokohama F, Wang G, Cerny D, Fink K, Blasco F, Shi PY. 2014. Activation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by dengue virus infection depotentiates balapiravir. J Virol 88:1740–1747. 10.1128/JVI.02841-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alhoot MA, Wang SM, Sekaran SD. 2011. Inhibition of dengue virus entry and multiplication into monocytes using RNA interference. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1410. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwissa M, Nakaya HI, Onlamoon N, Wrammert J, Villinger F, Perng GC, Yoksan S, Pattanapanyasat K, Chokephaibulkit K, Ahmed R, Pulendran B. 2014. Dengue virus infection induces expansion of a CD14(+)CD16(+) monocyte population that stimulates plasmablast differentiation. Cell Host Microbe 16:115–127. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peng X, Sova P, Green RR, Thomas MJ, Korth MJ, Proll S, Xu J, Cheng Y, Yi K, Chen L, Peng Z, Wang J, Palermo RE, Katze MG. 2014. Deep sequencing of HIV-infected cells: insights into nascent transcription and host-directed therapy. J Virol 88:8768–8782. 10.1128/JVI.00768-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szlavik L, Gyuris A, Minarovits J, Forgo P, Molnar J, Hohmann J. 2004. Alkaloids from Leucojum vernum and antiretroviral activity of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Planta Med 70:871–873. 10.1055/s-2004-827239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin LZ, Hu SF, Chai HB, Pengsuparp T, Pezzuto JM, Cordell GA, Ruangrungsi N. 1995. Lycorine alkaloids from Hymenocallis littoralis. Phytochemistry 40:1295–1298. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00372-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renard-Nozaki J, Kim T, Imakura Y, Kihara M, Kobayashi S. 1989. Effect of alkaloids isolated from Amaryllidaceae on herpes simplex virus. Res Virol 140:115–128. 10.1016/s0923-2516(89)80089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chatel-Chaix L, Fischl W, Scaturro P, Cortese M, Kallis S, Bartenschlager M, Fischer B, Bartenschlager R. 2015. A combined genetic-proteomic approach identifies residues within dengue virus NS4B critical for interaction with NS3 and viral replication. J Virol 89:7170–7186. 10.1128/JVI.00867-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy PD, Pogany J. 2011. The dependence of viral RNA replication on co-opted host factors. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:137–149. 10.1038/nrmicro2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chatel-Chaix L, Bartenschlager R. 2014. Dengue virus- and hepatitis C virus-induced replication and assembly compartments: the enemy inside—caught in the Web. J Virol 88:5907–5911. 10.1128/JVI.03404-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neufeldt CJ, Cortese M, Acosta EG, Bartenschlager R. 2018. Rewiring cellular networks by members of the Flaviviridae family. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:125–142. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller S, Sparacio S, Bartenschlager R. 2006. Subcellular localization and membrane topology of the dengue virus type 2 Non-structural protein 4B. J Biol Chem 281:8854–8863. 10.1074/jbc.M512697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ambrose RL, Mackenzie JM. 2011. A conserved peptide in West Nile virus NS4A protein contributes to proteolytic processing and is essential for replication. J Virol 85:11274–11282. 10.1128/JVI.05864-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roosendaal J, Westaway EG, Khromykh A, Mackenzie JM. 2006. Regulated cleavages at the West Nile virus NS4A-2K-NS4B junctions play a major role in rearranging cytoplasmic membranes and Golgi trafficking of the NS4A protein. J Virol 80:4623–4632. 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4623-4632.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller S, Kastner S, Krijnse-Locker J, Bühler S, Bartenschlager R. 2007. The non-structural protein 4A of dengue virus is an integral membrane protein inducing membrane alterations in a 2K-regulated manner. J Biol Chem 282:8873–8882. 10.1074/jbc.M609919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simanjuntak Y, Liang JJ, Lee YL, Lin YL. 2015. Repurposing of prochlorperazine for use against dengue virus infection. J Infect Dis 211:394–404. 10.1093/infdis/jiu377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smith JL, Stein DA, Shum D, Fischer MA, Radu C, Bhinder B, Djaballah H, Nelson JA, Fruh K, Hirsch AJ. 2014. Inhibition of dengue virus replication by a class of small-molecule compounds that antagonize dopamine receptor d4 and downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Virol 88:5533–5542. 10.1128/JVI.00365-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eyre NS, Kirby EN, Anfiteatro DR, Bracho G, Russo AG, White PA, Aloia AL, Beard MR. 2020. Identification of estrogen receptor modulators as inhibitors of flavivirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e00289-20. 10.1128/AAC.00289-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tohma D, Tajima S, Kato F, Sato H, Kakisaka M, Hishiki T, Kataoka M, Takeyama H, Lim CK, Aida Y, Saijo M. 2019. An estrogen antagonist, cyclofenil, has anti-dengue-virus activity. Arch Virol 164:225–234. 10.1007/s00705-018-4079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia F, Zou G, Fan J, Yuan Z. 2010. Identification of palmatine as an inhibitor of West Nile virus. Arch Virol 155:1325–1329. 10.1007/s00705-010-0702-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu Y, Chen YL, Herve M, Gu F, Shi PY, Blasco F. 2014. Development of a FACS-based assay for evaluating antiviral potency of compound in dengue infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol Methods 196:18–24. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rothwell C, Lebreton A, Young Ng C, Lim JY, Liu W, Vasudevan S, Labow M, Gu F, Gaither LA. 2009. Cholesterol biosynthesis modulation regulates dengue viral replication. Virology 389:8–19. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Durbin AP, Vargas MJ, Wanionek K, Hammond SN, Gordon A, Rocha C, Balmaseda A, Harris E. 2008. Phenotyping of peripheral blood mononuclear cells during acute dengue illness demonstrates infection and increased activation of monocytes in severe cases compared to classic dengue fever. Virology 376:429–435. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong KL, Chen W, Balakrishnan T, Toh YX, Fink K, Wong SC. 2012. Susceptibility and response of human blood monocyte subsets to primary dengue virus infection. PLoS One 7:e36435. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kobayashi S, Tokumoto T, Kihara M, Imakura Y, Shingu T, Taira Z. 1984. Alkaloidal constituents of Crinum latifolium and Crinum bulbispermum (Amaryllidaceae). Chem Pharm Bull 32:3015–3022. 10.1248/cpb.32.3015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nair J, Machocho A, Campbell W, Brun R, Viladomat F, Codina C, Bastida J. 2000. Alkaloids from Crinum macowanii. Phytochemistry 54:945–950. 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tram NTN, Titorenkova TV, Bankova VS, Handjieva N, Popov S. 2002. Crinum L. (Amaryllidaceae). Fitoterapia 73:183–208. 10.1016/S0367-326X(02)00068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lebrun S, Couture A, Deniau E, Grandclaudon P. 2003. A new synthesis of (+)- and (-)-cherylline. Org Biomol Chem 1:1701–1706. 10.1039/b302168h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kale BY, Shinde AD, Sonar SS, Shingate BB, Kumar S, Ghosh S, Venugopal S, Shingare MS. 2009. A short synthesis of +/–cherylline dimethyl ether. Beilstein J Org Chem 5:80. 10.3762/bjoc.5.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Couture A, Deniau E, Woisel P, Grandclaudon P, Carpentier JF. 1996. Base-induced cyclization of trimethoxy-o-aroyldiphenylphosphoryl methylbenzamide: a formal synthesis of (+/-)cherylline and (+/-)cherylline dimethylether. Tetrahedron Lett 37:3697–3700. 10.1016/0040-4039(96)00644-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manolov SP, Atanasova SN, Ghate M, Ivanov II. 2015. A brief review of cherylline synthesis. 54B:1301–1320. [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Andrade JP, Guo Y, Font-Bardia M, Calvet T, Dutilh J, Viladomat F, Codina C, Nair JJ, Zuanazzi JAS, Bastida J. 2014. Crinine-type alkaloids from Hippeastrum aulicum and H. calyptratum. Phytochemistry 103:188–195. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tallini LR, Torras-Claveria L, Borges WDS, Kaiser M, Viladomat F, Zuanazzi JAS, Bastida J. 2018. N-oxide alkaloids from Crinum amabile (Amaryllidaceae). Molecules 23:1277. 10.3390/molecules23061277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pépin G, Nejad C, Thomas BJ, Ferrand J, McArthur K, Bardin PG, Williams BR, Gantier MP. 2017. Activation of cGAS-dependent antiviral responses by DNA intercalating agents. Nucleic Acids Res 45:198–205. 10.1093/nar/gkw878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anton A, Mazeaud C, Freppel W, Gilbert C, Tremblay N, Sow AA, Roy M, Rodrigue‐Gervais IG, Chatel‐Chaix L. 2021. Valosin‐containing protein ATPase activity regulates the morphogenesis of Zika virus replication organelles and virus‐induced cell death. Cell Microbiol 23:e13302. 10.1111/cmi.13302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]